Page:Once a Week Jul - Dec 1859.pdf/441

Street, returning slowly to his flat above his shop—as all London tradesmen, yea, and many merchants, dwelt in his generation—still haunted between times by the green shady Mercers' Gardens, and youthful, sweet, quick Patience Chiswell, first beseeching him to save herself, and then to rescue another. It must have made an enormous difference to the self-collected young Whig to be so sued; for he could not deny the subsequent fact—though it disconcerted him greatly to admit it, even to himself, and he endeavoured strenuously to cheat his conscience and blink the new sensation—that the image of the carver and gilder's frank, transparent, light-hearted little daughter, grown all of a sudden distressed and pitiful, would make his calm, serious heart beat.

(To be continued.)

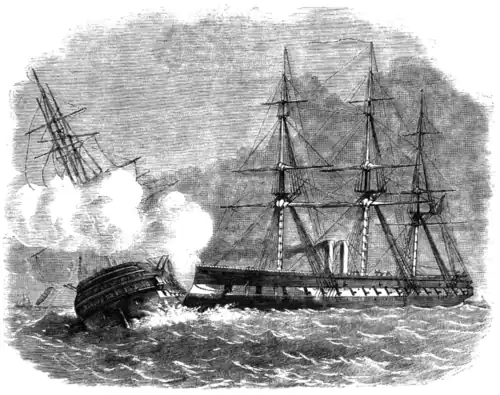

ENGLISH WAR SHIPS AND THEIR USES. By W. B. A.

The Steam-Ram.

With regard to the external form of the hull of a vessel, it must vary according to the purposes for which it is designed. If required to carry much cargo, it must be deep and square and wall-sided. If a sailing vessel, it must perforce have a broader beam than a steamer, to compensate for the leverage of the wind tending to overturn a very narrow vessel. If a steamer intended for war-purposes, there must be space for lodging the crew and for working the guns, unless intended chiefly for speed, in which case the longer the vessel in proportion to width, the faster she may be propelled through the water with a given power. And inasmuch as water naturally runs in rounded sections, the hollow section for the vessel's bottom is the form of least friction against the water. Eight breadths to a length, with hollow lines like those of a bayonet, would give good cleavage of the water; but unless it be very smooth water, the midship section must change to a flat or rounded bottom, or the vessel would be apt to capsize. The question of size is very important, as great size—other things being equal—gives increased speed and greater space for men and machinery, both for working and fighting.

There has existed a notion that wooden ships could not hold out against stone walls. One reason for this was, that the stone walls carried the heaviest batteries; yet Nelson at Copenhagen did not hesitate to pit his ships against them, and came off victorious. There is one undoubted advantage the ships possess. They can discharge their projectiles and move away, preventing the fortress-gunner, from getting their range. But latterly the size of ships' guns has been doubled, and fort guns also;