Page:EB1911 - Volume 27.djvu/392

supporting tissue of the brain and spinal cord. Consequently gliomata are only found in these two structures. it

Fig. 11.—Pseudo-neuroma: fibrous tumour growing from nerve sheath, and causing the fibres to be stretched over it.

Endothelioma.-Of late years a small class of tumour has been described as originating apparently from the endothelium lining the lesser blood and lymph channels. Many of the recorded examples have been connected with the mouth, the tongue, the palate or the parotid gland. Some of these tumours are quite innocent, others are typically malignant.

An Angeioma consists of a meshwork of blood-vessels bound together by a small amount of fat and fibrous tissue. Two varieties are described: (a) The simple naevus, or port-wine stain, scarcely deserves to be called a tumour. It appears as a reddish-blue discolouration of the skin due to over growth and dilatation of the underlying blood-vessels. This condition is most commonly found on the face or scalp, and may be of congenital origin. (b) In the cavernous naevus the vascular hypertrophy is on a larger scale, and may produce a definite pulsating tumour. Here, again, the head is the usual situation.

Fig. 12.—Ossifying periosteal sarcoma of fibula.

Sarcoma.—This is the malignant type of the connective-tissue tumour. The general arrangement of a sarcoma shows a mass of atypical cells loosely bound together by a small amount of connective tissue. The cells vary greatly in size and shape in different tumours, and in accordance with the prevailing type the following varieties of sarcoma have been described: (i.) round-cell sarcoma, (ii.) spindle-cell sarcoma, (iii.) melanotic sarcoma, (iv.) myeloid sarcoma. The first two groups contain the great majority of all sarcomata, and may occur in almost any part of the body, but they are especially liable to attack the bones (fig. 12). A sarcoma of bone may be either periosteal when it grows from the periosteum covering the outer surface of the bone, or endosteal when it lies in the medullary cavity. A peculiar form of sarcoma is found in the parotid and other salivary glands. The cells are usually spindle-shaped, and among them lie scattered masses of cartilage and fibrous tissue. These tumours are seldom very malignant, and dissemination is rare (fig. 13). The melanotic sarcoma is of a brown or black colour owing to the presence of granules of pigment (melanin) in and among the tumour cells. A melanotic sarcoma may arise from a pigmented wart or mole, or

Fig. 13.—Malignant tumour of the parotid gland.

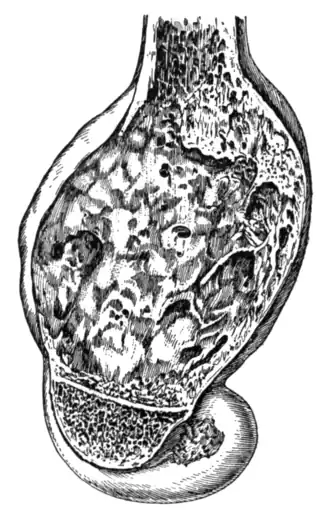

from the pigmented layers of the retina. The primary growth is usually small, but dissemination occurs with great rapidity throughout the body. The myeloid sarcoma, or myeloma (fig. 14). is composed of very large cells like those of bone-marrow from which it is probably derived. It is only found in the interior of bones, chiefly in those of the arm and leg. The degree of malignancy is low, dissemination never occurs, and recurrence after operation is rare.

Fig. 14.—Lower end of a femur in longitudinal section, showing a myeloma.

II.—Epithelial Tumours.

Papilloma.—The familiar example of a papilloma is the simple wart, which is formed by a proliferation of the squamous epithelium of the skin (fig. 3). It seems probable that some warts are of an infective nature, for instances of direct contagion are not uncommon. Occasionally warts are pigmented, and are then liable to be the seat of a melanotic sarcoma. Papillomata are also found in the bladder (fig. 15), as long delicate filaments growing from the bladder wall. These consist of a connective tissue core covered by a thin layer of epithelium.

Fig. 15.—Villous papilloma of the bladder.

Adenoma.—(Figs. 1a and 1b). The glandular tumours are of very common occurrence in the breast, the ovary and the intestinal canal. The structure of an adenoma of the breast has already been described (vide supra), and the structure of other adenomata is on the same general plan. The main features of an innocent glandular tumour are: (a) the presence of a rounded, painless swelling with a well-defined margin; (b) the swelling is freely movable in the surrounding tissues, and if it lies close beneath the skin it is not attached thereto; (c) there is no enlargement of the neighbouring lymphatic glands.

carcinoma.—The following varieties of carcinoma are described:—

i. Squamous-cell carcinoma (fig. 4), arising from those parts of the body covered by squamous epithelium, namely the skin, the mouth, the pharynx, the upper part of the oesophagus and the bladder.

ii. Spheroidal-cell carcinoma (figs. 2a and 2b), arising from spheroidal epithelium, as in the breast, the pylorus, the pancreas, the kidney and the prostrate.

iii. Columnar-cell carcinoma (figs. 16 and 17), arising from columnar epithelium, as in the intestine.

The general histology of these tumours corresponds to that of a spheroidal-cell carcinoma already described (vide supra), the only variation between the three groups being in the shape of the cells. The clinical characteristics of a carcinoma, whatever its situation, are: (a) the presence of a swelling which has no well defined margin, but fades away into the surrounding tissues to which it is fixed; (b) when the tumour lies near the skin (e.g. a carcinoma