Page:EB1911 - Volume 25.djvu/190

vertebrae vary from ten in some of the whales and the peba armadillo to twenty-four in the two-toed sloth, though thirteen or fourteen is the commonest number. In the anterior part of the thoracic region the spines point backward, while in the posterior thoracic and lumbar regions they have a forward direction. There is always one spine in the posterior thoracic region, which is vertical, and the vertebra which bears this is known as the anticlinal vertebra. The

|

|

| Fig. 8.—Anterior Surface of Sixth Cervical Vertebra of Dog. | Fig. 9.—Side View of the First Lumbar Vertebra of a Dog (Canis familiaris). |

| s Spinous process. | s Spinous process. |

| az Anterior zygapophysis. | m Metapophysis. |

| v Vertebrarterial canal. | az Anterior zygapophysis. |

| t Transverse process. | pz Posterior zygapophysis. |

| t′ Its costal lamella. | a Anapophysis. |

| t Transverse (costal) process. |

lumbar vertebrae vary from two in the Ornithorhynchus and some of the armadillos to twenty-one in the dolphin, the average number being probably six. Both the mammillary and accessory tubercles (meta- and ana-pophyses) are in some forms greatly enlarged. It is usually held that the former are morphologically muscular processes while the latter represent the transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae. In the American edentates additional articular processes (zygapophyses) are developed, so that these animals are sometimes divided from the old-world edentates and spoken of as Xenarthra.

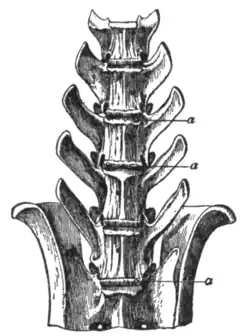

Lying ventral to the intervertebral disks in many mammals small paired ossicles are occasionally found; these are called intercentra and are ossifications in the hypochordal bar (see subsection on embryology). They probably represent the places where the chevron bones or haemal arches would be attached and are the serial homologues of the anterior arch of the atlas (see fig. 10).

Boulenger has pointed out that these intercentra, either as paired or median ossicles, are often found in lizards (P.Z.S., 1891, p. 114). The sacrum consists of true sacral vertebrae, which directly articulate with the sacrum, and false, which are caudal vertebrae fused with the others to form a single bone. There is also reason to believe that vertebrae which are originally lumbar become secondarily included in the sacrum because in the development of man the pelvis is at first attached to the thirtieth vertebra, but gradually shifts forward until it reaches the twenty-fifth, twenty-sixth and twenty-seventh; the twenty-fifth or first sacral vertebra has, however, a frequent tendency to revert to the lumbar type and sometimes may do so on one side but not on the other. A. Paterson, on the other hand, brings forward evidence to prove that the human sacrum undergoes a backward rather than a forward shifting (Scientif. Trans. R. Dublin Society, vol. v., ser. 11, p. 123). Taking the vertebrae which fuse together as an arbitrary definition of the sacrum, we find that the number may vary from one in Cercopithecus patas to thirteen in some of the armadillos, and, if the Cetacea are included, seventeen in the bottle-nosed dolphin, Tursiops. Four seems to be about the average of sacral vertebrae in the mammalian class and of these one or two are true sacral. In some of the Edentata the posterior sacral vertebrae are fused with the ischium, in other words the great sacro-sciatic ligament is ossified. The lateral

After F. G. Parsons, "On Anatomy of Atherura Africana," Proc. Zool. Soc., 1894.

Fig. 10.—The Intercentra of the Lower Part of the Vertebral Column, a, a, a, Intercentra.

centres of ossification which form the articular surface for the ilium probably represent rib elements. The caudal or tail vertebrae vary from none at all in the bat Megaderma to forty-nine in the pangolin (Manis macrura). The anterior ones are remarkable for usually having chevron bones (shaped like a V) on the ventral surface of the intercentral articulation. These protect the caudal vessels and give attachment to the ventral tail muscles. The ribs in mammals correspond in number to the thoracic vertebrae. In monotremes the three parts of the rib (dorsal, intermediate and ventral) already noticed in the reptiles are found, but usually the intermediate part is suppressed. The ventral part generally remains cartilaginous as it does in man though sometimes it ossifies as in the armadillos. In the typical pronograde mammals the shape of the ribs differs from that of the higher Primates and man: they are so curved that the dorso-ventral diameter of the thorax is greater than the transverse while in the higher Primates the thorax is broader from side to side than it is dorso-ventrally. In this respect the bats agree with man and the lemurs with the pronograde mammals.

Fig. 11.—Anterior Surface of Fourth Caudal Vertebra of Porpoise (Phocaena communis).

s Spinous process.

m Metapophysis.

t Transverse process.

h Chevron bone.

In some whales the first rib articulates by an apparently double head with two vertebrae; this is probably the result of a cervical rib joining it a little way from the vertebral column, and the result is homologous with those cases in man in which a cervical rib joins the first thoracic as it sometimes does. In the toothed whales, of which the porpoise is an example, the more posterior ribs lose their heads and necks and only articulate with the transverse processes. The sternum of mammals typically consists of from seven to nine narrow segments or sternebrae, the first of which (presternum) is often broader than those behind. As a rule the second rib articulates with the interval between the first and second pieces, but sometimes, as in the gibbon, it is the third rib which does so. When this is the case, as it sometimes is in man, the first two sternebrae have probably fused (see A. Keith, Journ. Anat. and Phys. xxx. 275). The segmental character of the separate sternebrae contrasts strongly with the intersegmental of the ribs. When the pectoralis major muscle is largely developed, as in the mole and bats, the sternum, especially the presternum, develops a keel as in birds. In the toothed whales there is usually a cleft or perforation throughout life between the two lateral halves of the sternum. In the whalebone whales the mesosternum is suppressed and consequently only the first ribs reach the sternum; this is of great interest when the oblique position of the diaphragm (see art. Diaphragm) in these animals is remembered, and makes one suspect that the development of the sternum in mammals is dependent on and subservient to the attachment of the diaphragm. The broadened thorax of the anthropomorpha is accompanied by a broadened sternum and the sternebrae of the mesosternum fuse together early, though in the orang they not only remain separate but each half of them remains separate until the animal is half -grown. The episternum is represented by small ossicles which occasionally occur in man, while in the Omithorhynchus and the tapir there is a separate bone in front (cephalad) of the presternum which in the former animal is distinct at first from the interclavicle, and this probably represents the episternum, though it was called by W. K. Parker by the noncommittal name of proösteon.

For further details and literature see S. H. Reynolds, The Vertebrate Skeleton (Cambridge, 1897); W. H. Flower and H. Gadow,

Fig. 12.—Sternum and strongly ossified Sternal Ribs of Great Armadillo (Priodon gigas). ps, Presternum; xs, xiphisternum.