Page:EB1911 - Volume 22.djvu/973

strengthened at intervals by counterforts. The thickness of the wall varies from 11 ft. 6 in. at the base to 3 ft. at the top, and is surmounted by a dressed cornice and coping; the length is 340 yards. The work was constructed, in 1888, at a cost of £10,000, or £29, 8s. per lineal yard.

| ||

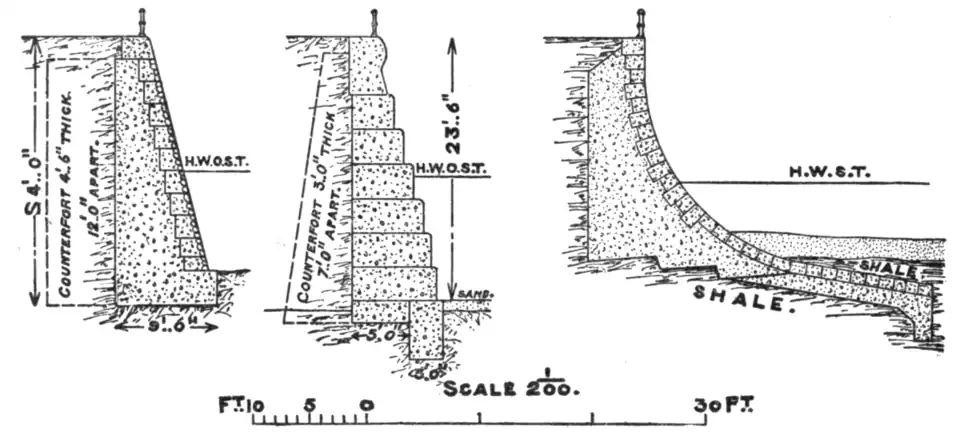

| Fig. 4.—Sea-wall at Hove. | Fig. 5.—Sea-wall at Margate. | Fig. 6.—Sea-wall at Scarborough. |

Walls with almost vertical faces, or slightly stepped, appear to be the best. Unless, however, the foreshore consists of hard rock, or a raised beach maintained by groynes, a wall of this kind should be protected by an apron, in order to prevent the destructive undermining to which such forms of wall are necessarily liable.

Fig. 7.—Sea-wall at Bridlington.

Where the coast is fringed with sand dunes, and the beach protected from erosion by a regular series of groynes, as at Ostend (Belgium), the sand dunes, or an embankment for a promenade in front of them, may be sufficiently protected by a simple slope, paved with brickwork or masonry, and having a maximum inclination of two to one. The paving requires to be laid on a bed of clay, rubble or concrete. Parts of the sea bank at Ostend (see fig. 8) have been carried out beyond high-water mark to gain a strip of land for the esplanade; and these portions have had to be protected from undermining at the toe with piles and planks, and an apron of concrete or pitching, laid on fascines, extending down the foreshore. For the parts above high-water mark a short paved slope, with moderate protection at the toe, has been found sufficient. The top face of these slopes is reflexed so as to protect the esplanade from surf during storms.

Fig. 8.—Sea Embankment at Ostend.

Sea-walls are very costly and, while temporarily resisting, do not diminish, but actually increase, the erosive action of the sea. In short, sea-walls are a most unsatisfactory type of protective work.

The protection afforded to the coast by groynes is based on a totally different principle, which may be summarized as that of promoting natural accretion by the construction of artificial shelter. Along most coasts there is a littoral drift of sand or shingle; by means of groynes, projecting from the coast-line down the beach, this drift may be intercepted so as to produce accretion to the foreshore, where previously there has been constant erosion. The problem, however, of coast protection by this method presents difficulties. Littoral drift is the product of erosion, and the fate of a large portion of this drift is to be deposited in deep water. Any scheme, therefore, of stopping erosion altogether by means of groynes would be purely chimerical; in the same way, partial failure of groynes, from lack of drift and inability to stop wastage, must be expected in many localities. Another difficulty may be illustrated by the action of such natural projections as Dungeness: this point, by completely arresting the easterly drift of shingle, causes a rapid accretion to the beach on the one side, but a corresponding denudation on the other. The old type of high groyne, erected at Cromer and Hastings, has produced the same undesirable result; moreover, the general effect of groyning certain portions of the foreshore is to render the adjacent unprotected portions more liable to erosion. Nevertheless, the benefit which may be derived locally from suitable groyning is very great. The timber groynes erected between Lancing and Shoreham raised the shingle beach sufficiently to cause high-water mark to recede 85 ft. seawards in the course of a few years.

The eroding action of the river Scheldt in front of Blankenberghe has been arrested by carrying out groynes at right angles to the coast-line, and down to below low water (see figs. 9, 10).

Fig. 9.—Groynes on North Sea coast at Blankenberghe.

Fig. 10.—Sections of Groynes at Blankenberghe.

These, on the average, are about 820 ft. long and 680 ft. apart: they are made wide, with a curved top raised only slightly above the beach, so as to minimize the scour from currents and wave action, and facilitate the even