Page:EB1911 - Volume 22.djvu/936

RATRAMNUS (d. c. 868), a theological controversialist of the second half of the 9th century, was a monk of the Benedictine abbey of Corbie near Amiens, but beyond this fact very little of his history has been preserved. He is best known by his treatise on the Eucharist (De corpore et sanguine Domini liber), in which he controverted the doctrine of transubstantiation as taught in a similar work by his contemporary Radbertus Paschasius. Ratramnus sought in a way to reconcile science and religion, whereas Radbertus emphasized the miraculous. Ratramnus’s views failed to find acceptance; their author was soon forgotten, and, when the book was condemned at the synod of Vercelli in 1050, it was described as having been written by Johannes Scotus Erigena at the command of Charlemagne. In the Reformation it again saw the light; it was published in 1532 and immediately translated. In the controversy about election, when appealed to by Charles the Bald, Ratramnus wrote two books De praedestinatione Dei, in which he maintained the doctrine of a twofold predestination; nor did the fate of Gottschalk deter him from supporting his view against Hincmar as to the orthodoxy of the expression “trina Deitas.” Ratramnus perhaps won most glory in his own day by his Contra Graecorum opposita, in four books (868), a valued contribution to the controversy between the Eastern and Western Churches which had been raised by the publication of the encyclical letter of Photius in 867. An edition of De corpore et sanguine Domini was published at Oxford in 1859.

See the article by G. Steitz and Hauck in Hauck’s Realencyklopädie für protest. Theologie, Band xvi. (Leipzig, 1905); Naegle, Ratramnus und die heilige Eucharistie (Vienna, 1903); Schnitzer, Berengar von Tours; and A. Harnack, History of Dogma, v., pp. 309–322 (1894–9).

RATTAZZI, URBANO (1808–1873), Italian statesman, was

born on the 29th of June 1808 at Alessandria, and from 1838

practised at the bar. In 1848 he was sent to the chamber of

deputies in Turin as representative of his native town. By

his debating powers he contributed to the defeat of the Balbo

ministry, and for a short time held the portfolio of public instruction;

afterwards, in the Gioberti cabinet, he became

minister of the interior, and on the retirement of the last-named

in 1849 he became practically the head of the government.

The defeat at Novara compelled the resignation of Rattazzi

in March 1849. His election as president of the chamber in

1852 was one of the earliest results of the so-called “connubio”

with Cavour, i.e. the union of the moderate men of the Right

and of the Left; and having become minister of justice in 1853

he carried a number of measures of reform, including that for

the suppression of certain of the monastic orders. During a

momentary reaction of public opinion he resigned office in 1858,

but again entered the cabinet under La Marmora in 1859 as

minister of the interior. In consequence of the negotiations

for the cession of Nice and Savoy he again retired in January

1860. He was entrusted with the formation of a new ministry

in March 1862, but in consequence of his policy of repression

towards Garibaldi at Aspromonte he was driven from office

in the following December. He was again prime minister in

1867, from April to October. He died at Frosinone on the 5th

of June 1873. His wife, whom he married in 1863, was a remarkable

woman. She was the daughter of Sir Thomas Wyse, British

plenipotentiary at Athens, and Laetitia Bonaparte, niece of

Napoleon I. Born in Ireland in 1833, she was educated in Paris,

and in 1848 married a rich Alsatian named Solms; but the prince-president

refused to recognize her, and in 1852 she was expelled

from Paris. Her husband died soon after; and calling herself the

Princesse Marie de Solms, she spent her time in various fashionable

places and dabbled in literature, Eugène Sue and François

Ponsard being prominent in her court of admirers. She published

Les Chants de l’exilée (1859) and some novels. After

Rattazzi’s death, she married (1877) a Spaniard named Rute;

she died in February 1902.

See Madame Rattazzi, Rattazzi et son temps (Paris, 1881); Bolton King, History of Italian Unity (London, 1899).

RATTLESNAKE. Rattlesnakes are a small group of the

sub-family of pit-vipers (Crotalinae, see Snakes; Viperidae),

characterised by a tail which terminates in a chain of horny,

loosely connected rings, the so-called “rattle.” The “pit”

by which the family is distinguished from the ordinary vipers

is a deep depression in the integument of the sides of the snout,

between the nostrils and the eye; its physiological function

is unknown. The rattle is a complicated and highly specialized

organ, developed from the simple conical scale or epidermal

spine, which in the majority of snakes forms the termination

of the general integument of the tail. The bone by which the

root of the rattle is supported consists of the last caudal

vertebrae, from three to eight in number, which are enlarged, dilated,

compressed and coalesced (fig. 1, a). This bone is covered

with thick and vascular cutis, transversely divided by two

constrictions into three portions, of which the proximal is

larger than the median, and the median much larger than the

distal. This cuticular portion constitutes the matrix of a horny

epidermoid covering which closely fits the shape of the underlying

soft part and is the beginning of the rattle, as it appears

in young rattlesnakes before they have shed their skin for the

first time. When the period of a renewal of the skin approaches

a new covering of the extremity of the tail is formed below

the old one, but the latter, instead of being cast off with the

remainder of the epidermis, is retained by the posterior swelling

of the end of the tail, forming now the first loose joint of the

rattle. This process is repeated on succeeding moultings—the

new joints being always larger than the old ones as long as

the snake grows. Perfect rattles therefore taper towards the

point, but generally the oldest (terminal) joints wear away in

time and are lost. As rattlesnakes shed their skins more than

once every year, the number of joints of the rattle does not

indicate the age of the animal but the number of exuviations

which it has undergone. The largest rattle in the British

Museum has twenty-one joints. The rattle consists thus of

a variable number of dry, hard, horny cup-shaped joints,

each of which loosely grasps a portion of the preceding, and all

of which are capable of being shaken against each other. If the

interspaces between the joints are filled with water, as often

happens in wet weather, no noise can be produced. The motor

power lies in the lateral muscles of the tail, by which a vibratory

motion is communicated to the rattle, the noise produced being

similar to that of a child’s rattle and perceptible at a distance

of from 10 to 20 yds.

|

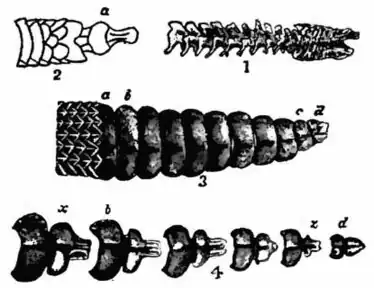

Fig. 1.—Rattle of Rattlesnake (after Czermak). |

| 1. Caudal vertebrae, the last coalesced in a single bone a. 2. End of tail (rattle removed); a. cuticular matrix covering terminal bone. 3. Side view of a rattle; c and d the oldest, a and b the youngest joints. 4. A rattle with joints disconnected; x fits into b and is covered by it; z into d in like manner. |

The habit of agitating the tail is not peculiar to the rattlesnake, but has been observed in other venomous and innocuous snakes with the ordinary tail, under the influence of fear or anger. It is significant that the tip of such snakes is sometimes rather conspicuously coloured and covered with peculiarly modified