Page:EB1911 - Volume 21.djvu/595

towards rectifying these faults. He called in the aid of professed

men of science—Tiberius Cavallo, who in 1788 published his

calculations of the tension, and Dr Gray, of the British Museum.

The problem was solved by dividing the sound-board bridge,

the lower half of which was advanced to carry the bass strings,

which were still of brass. The first attempts to equalize the

tension and improve the striking-place were here set forth, to

the great advantage of the instrument, which in its wooden

construction might now be considered complete. The greatest

pianists of that epoch, except Mozart and Beethoven, were

assembled in London—Clementi, who first gave the pianoforte

its own character, raising it from being a mere variety of the

harpsichord, his pupils Cramer and for a time Hummel, later

on John Field, and also the brilliant virtuosi Dussek and Steibelt.

To please Dussek, Broadwood in 1791 carried his five-octave,

F to F, keyboard, by adding keys upwards, to five and a half

octaves, F to C. In 1794 the additional bass half octave to C,

which Shudi had first introduced in his double harpsichords,

was given to the piano. Steibelt, while in England, instituted

the familiar signs for the employment of the pedals, which

owes its charm to excitement of the imagination instigated by

power over an acoustical phenomenon, the sympathetic vibration

of the strings. In 1799 Clementi founded a pianoforte

manufactory, to be subsequently developed and carried on by

Messrs Collard.

The first square piano made in France is said to have been constructed in 1776 by Sebastian Erard, a young Alsatian. In 1786 he came to England and founded the London manufactory of harps and pianofortes bearing his name. That eminent mechanician and inventor is said to have at first adopted for his pianos the English models. Erard. However, in 1794 and 1801, as is shown by his patents, he was certainly engaged upon the elementary action described as appertaining to Gosselin’s piano, of probably German origin. In his long-continued labour of inventing and constructing a double escapement action, Erard appears to have sought to combine the English power of gradation of tone with the German lightness of touch. He took out his first patent for a “repetition” action in 1808, claiming for it “the power of giving repeated strokes without missing or failure, by very small angular motions of the key itself.” He did not, however, succeed in producing his famous repetition or double escapement action until 1821; it was then patented by his nephew Pierre Erard, who, when the patent expired in England in 1835, proved a loss from the difficulties of carrying out the invention, which induced the House of Lords to grant an extension of the patent.

|

| Fig. 26.—Erard’s Double Escapement Action, 1884. The double escapement or repetition is effected by a spring in the balance pressing the hinged lever upwards, to allow the hopper which delivers the blow to return to its position under the nose of the hammer, before the key has risen again. |

Erard invented in 1808 an upward bearing to the wrest-plank bridge, by means of agraffes or studs of metal through holes in which the strings are made to pass, bearing against the upper side. The wooden bridge with down-bearing strings is clearly not in relation with upward-striking hammers, the tendency of which must be to raise the strings from the bridge, to the detriment of the tone. A long brass bridge on this principle was introduced by William Stodart in 1822. A pressure-bar bearing of later introduction is claimed for the French maker, Bord. The first to see the importance of iron sharing with wood (ultimately almost supplanting it) in pianoforte framing Hawkins. was a native of England and a civil engineer by profession, John Isaac Hawkins, known as the inventor of the ever-pointed pencil. He was living at Philadelphia, U.S.A., when he invented and first produced the familiar cottage pianoforte—“portable grand” as he then called it. He patented it in America, his father, Isaac Hawkins, taking out the patent for him in England in the same year, 1800. It will be observed that the illustration here given (fig. 28) represents a wreck; but a draughtsman’s restoration might be open to question.

|

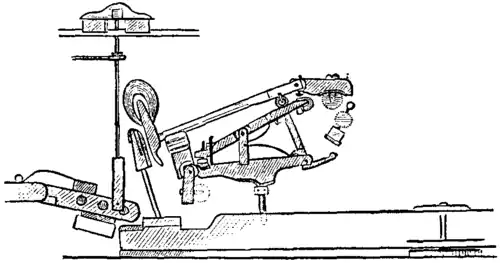

| Fig. 27.—Steinway’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. The double escapement as in Erard’s, but with shortened balance and usual check. |

There had been upright grand pianos as well as upright harpsichords, the horizontal instrument being turned up upon its wider end and a keyboard and action adapted to it. William Southwell, an Irish piano-maker, had in 1798 tried a similar experiment with a square piano, to be repeated in later years by W. F. Collard of London; but Hawkins was the first to make a piano, or pianino, with the strings descending to the floor, the keyboard being raised, and this, although at the moment the chief, was not his only merit. He anticipated nearly every discovery that has since been introduced as novel. His instrument (fig. 28) is in a complete iron frame, independent of the case; and in this frame, strengthened by a system of iron resistance rods combined with an iron upper bridge, his sound-board is entirely suspended.

|

| Fig. 28.—Hawkins’s Portable Grand Piano, 1800. An upright instrument, the original of the modern cottage piano or pianino. In Messrs Broadwood’s museum and unrestored. |

An apparatus for tuning by mechanical screws regulates the tension of the strings, which are of equal length throughout. The action, in metal supports, anticipates Wornum’s in the checking, and still later ideas in a contrivance for repetition. This remarkable bundle of inventions was brought to London and exhibited by Hawkins himself;