Page:EB1911 - Volume 21.djvu/594

harpsichord, in 1745. When Mason imported a pianoforte in

1755, Fulke Greville’s could have been no longer unique. The

Italian origin of Father Wood’s piano points to a copy of Cristofori,

but the description of its capabilities in no way confirms this

supposition, unless we adopt the very possible theory that the

instrument had arrived out of order and there was on one in

London who could put it right, or would perhaps divine that it

was wrong. Burney further tells us that the arrival in London

of J. C. Bach in 1759 was the motive for several of the second-rate

harpsichord makers trying to make pianofortes, but with

no particular success. Of these Americus Backers (d. 1776),

Backers.

said to be a Dutchman, appears to have gained the

first place. He was afterwards the inventor of

the so-called English action, and as this action is based upon

Cristofori’s we may suppose he at first followed Silbermann in

copying the original inventor. There is an old play-bill of

Covent Garden in Messrs Broadwood’s possession dated the

16th of May 1767, which has the following announcement:—

“End of Act 1. Miss Brickler will sing a favourite song from Judith, accompanied by Mr Dibdin on a new instrument call’d Piano Forte.”

|

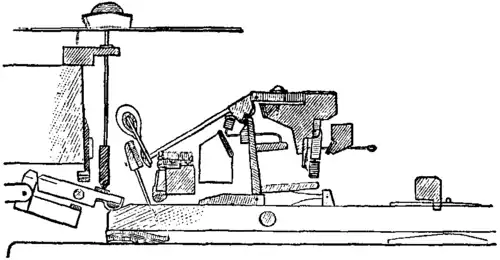

| Fig. 23.—Grand Piano Action, 1776. The “English” action of Americus Backers. |

The mind at once reverts to Backers as the probable maker of this novelty. Backers’s “Original Forte Piano” was played at the Thatched House in St James’s Street, London, in 1773. Ponsicchi has found a Backers grand piano at Pistoria, dated that year. It was Backers who produced the action continued in the direct principle by the firm of Broadwood, or with the reversed lever and hammer-butt introduced by the firm of Collard in 1835.

|

| Fig. 24.—Broadwood’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. English direct mechanism. |

The escapement lever is suggested by Cristofori’s first action, to which Backers has added a contrivance for regulating it by means of a button and screw. The check is from Cristofori’s second action. No more durable action has been constructed, and it has always been found equal, whether made in England or abroad, to the demands of the Broadwood; Stodart. most advanced virtuosi. John Broadwood and Robert Stodart were friends, Stodart having been Broadwood’s pupil; and they were the assistants of Backers in the installation of his invention. On his deathbed he commended it to Broadwood’s care, but Stodart appears to have been the first to advance it—Broadwood being probably held back by his partnership with his brother-in-law, the son of Shudi, in the harpsichord business. (The elder Shudi had died in 1773.) Stodart soon made a considerable reputation with his “grand” pianofortes, a designation he was the first to give them. In Stodart’s grand piano we first find an adaptation from the lyrichord of Plenius, of steel arches between the wrest-plank and belly-rail, bridging the gap up which the hammers rise, in itself an important cause of weakness. These are not found in any contemporary German instruments, but may have been part of Backers’s.

|

| Fig. 24.—Broadwood’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. English direct mechanism. |

|

| Fig. 25.—Collard’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. English action, with reversed hopper and contrivance for repetition added. |

Imitation of the harpsichord by “octaving” was at this time an object with piano makers. Zumpe’s small square piano had met with great success; he was soon enabled to retire, and his imitators, who were legion, continued his model with its hand stops for the dampers and sourdine, with little change but that which straightened the keys from the divergences inherited from the clavichord. John Broadwood took this domestic instrument first in hand to improve it, and in the year 1780 succeeded in entirely reconstructing it. He transferred the wrest-plank and pins from the right-hand side, as in the clavichord, to the back of the case, an improvement universally adopted after his patent, No. 1379 of 1783, expired. In this patent we first find the damper and piano pedals, since universally accepted, but at first in the grand pianofortes only. Zumpe’s action remaining with an altered damper, another inventor, John Geib, patented (No. 1571 of 1786) the hopper with two separate escapements, one of which soon became adopted in the grasshopper of the square piano, it is believed by Geib himself; and Petzold, a Paris maker, appears to have taken later to the escapement effected upon the key. We may mention here that the square piano was developed and continued in England until about the year 1860, when it went out of fashion.

To return to John Broadwood—having launched his reconstructed square piano, he next turned his attention to the grand piano to continue the improvement of it from the point where Backers had left it. The grand piano was in framing and resonance entirely on the harpsichord principle, the sound-board bridge being still continued in one undivided length. The strings, which were of brass wire in the bass, descended in notes of three unisons to the lowest note of the scale. Tension was left to chance, and a reasonable striking line or place for the hammers was not thought of. Theory requires that the notes of octaves should be multiples in the ratio of 1 to 2, by which, taking the treble clef C at one foot, the lowest F of the five-octave scale would require a vibrating length between the bridges of 12 ft. As only half this length could be conveniently afforded, we see at once a reason for the above-mentioned deficiencies. Only the three octaves of the treble, which had lengths practically ideal, could be tolerably adjusted. Then the striking-line, which should be at an eighth or not less than a ninth or tenth of the vibrating length, and had never been cared for in the harpsichord, was in the lowest two octaves out of all proportion, with corresponding disadvantage to the tone. John Broadwood did not venture alone upon the path