Page:EB1911 - Volume 21.djvu/592

equal distances (unlike the harpsichord), the dampers lying

between the pairs of unisons.

Cristofori died in 1731. He had pupils,[1] but did not found a school of Italian pianoforte-making, perhaps from the peculiar Italian conservatism in musical instruments we have already remarked upon. The essay of Scipione Maffei was translated into German, in 1725, by König, the court poet at Dresden, and friend of Gottfried Silbermann, the renowned organ builder and harpsichord and clavichord maker.[2] Incited by this publication, and perhaps by having seen in Dresden one of Silbermann. Cristofori’s pianofortes, Silbermann appears to have taken up the new instrument, and in 1726 to have manufactured two, which J. S. Bach, according to his pupil Agricola, pronounced failures. The trebles were too weak; the touch was too heavy. There has long been another version to this story, viz. that Silbermann borrowed the idea of his action from a very simple model contrived by a young musician named Schroeter, who had left it at the electoral court in 1721, and, quitting Saxony to travel, had not afterwards claimed it. It may be so; but Schroeter’s letter, printed in Mitzler’s Bibliothek, dated 1738, is not supported by any other evidence than the recent discovery of an altered German harpsichord, the hammer action of which, in its simplicity, may have been taken from Schroeter’s diagram, and would sufficiently account for the condemnation of Silbermann’s earliest pianofortes if he had made use of it. In either case it is easy to distinguish between the lines of Schroeter’s interesting communications (to Mitzler, and later to Marpurg) the bitter disappointment he felt in being left out of the practical development of so important an instrument.

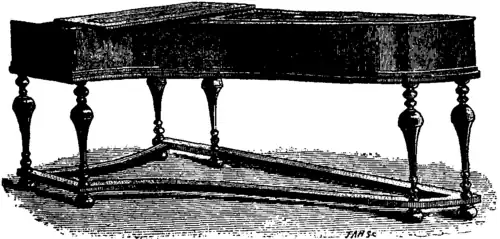

But, whatever Silbermann’s first experiments were based upon, it was ascertained, by the investigations of A. J. Hipkins, that he, when successful, adopted Cristofori’s pianoforte without further alteration than the compass and colour of the keys and the style of joinery of the case. In the Silbermann grand pianofortes, in the three palaces at Potsdam, known to have been Frederick the Great’s, and to have been acquired by that monarch prior to J. S. Bach’s visit to him in 1747, we find the Cristofori framing, stringing, inverted wrest-plank and action complete. Fig. 15 represents the instrument on which J. S. Bach played in the Town Palace, Potsdam.

|

| Fig. 15.—Silbermann Forte Piano; Stadtschloss, Potsdam, 1746. |

|

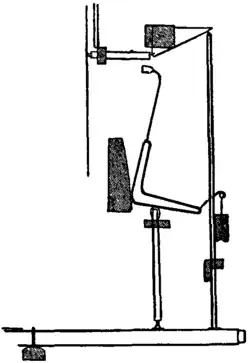

| Fig. 16.—Frederici’s Upright Grand Piano Action, 1745. In the museum of the Brussels Conservatoire. |

It has been repeatedly stated in Germany that Frederici, of Gera in Saxony, an organ builder and musical instrument maker, invented the square or table-shaped piano, the “fort bien,” as he is said to have called it, about 1758–1760. No square piano by this maker is forthcoming, though an “upright grand” piano, made by Domenico del Frederici. Mela in 1739, with an action adapted from Cristofori’s has been discovered by Signor Ponsicchi of Florence. Victor Mahillon of Brussels, however, acquired a Frederici “upright grand” piano, dated 1745 (fig. 16). In Frederici’s upright grand action we have not to do with the ideas of either Cristofori or Schroeter; the movement is practically identical with the hammer action of a German clock, and has its counterpart in a piano at Nuremberg; a fact which needs further elucidation. We note here the earliest example of the leather hinge, afterwards so common in piano actions and only now going out of use. Where are we to look for Schroeter’s copyist if not found in Silbermann, Frederici, or, as we shall presently see, perhaps J. G. Wagner? It might be in the harpsichord we have mentioned, which, made in 1712 by one Brock for the elector of Hanover (afterwards George I. of England), was by him presented to the Protestant pastor of Schulenberg, near Hanover, and has since been rudely altered into a pianoforte (fig. 17). There is an altered harpsichord in the museum at Basel which appears to have been no more successful. But an attempted combination of harpsichord and pianoforte appears as a very early intention. The English poet Mason, the friend of Gray, bought such an instrument at Hamburg in 1755, with “the cleverest mechanism imaginable.”

|

| Fig. 17.—Hammer and Lifter of altered Harpsichord by Brock. Instrument in the collection of Mr Kendrick Pyne, Manchester. |

It was only under date of 1763 that Schroeter[3] published for the first time a diagram of his proposed invention, designed more than forty years before. It appeared in Marpurg’s Kritische Briefe Schroeter; Zumpe. (Berlin, 1764). Now, immediately after, Johann Zumpe, a German in London, who had been one of Shudi’s workmen, invented or introduced (for there is some tradition that Mason had to do with the invention of it)[4] a square piano, which was to become the most popular domestic instrument. It would seem that Zumpe was in fact not the inventor of the square piano, which appears to have been well known in Germany before his date, a discovery made by Mr George Rose. In Paul de Wit’s Musical Instrument Museum—formerly in Leipzig, now transferred to Cologne—there is a small square piano, 27 in. long, 10 in. wide and 41/2 in. high, having a contracted keyboard of 3 octaves and 2 notes. The action of this small instrument is practically identical in every detail with that of the square pianofortes made much later by Zumpe (Paul de Wit, Katalog des musikhistorischen Museums, Leipzig, 1903. No. 55, illustration, p. 38). Inside is inscribed: “Friedrich Hildebrandt, Instrumentenmacher in Leipzig, Quergasse,” with four figures

- ↑ See Cesare Ponsicchi, Il Pianoforte, sua origine e sviluppo (Florence, 1876), p. 37.

- ↑ This translation, published at Hamburg and reproduced in extenso, may be read in Dr Oscar Paul’s Geschichte des Claviers (Leipzig, 1868).

- ↑ For arguments in favour of Schroeter’s claim to the invention of the pianoforte see Dr Oscar Paul, op. cit. pp. 85–104, who was answered by A. J. Hipkins in Grove’s Dict. of Music and Musicians.

- ↑ Mason really invented the “celestina” (known as Adam Walker’s patent No. 1020), as we know from the correspondence of Mary Granville. Under date of the 11th of January 1775 she describes this invention as a short harpsichord 2 ft. long, but played with the right hand only. The left hand controlled a kind of violin-bow, which produced a charming sostinente, in character of tone between the violin tone and that of musical glasses.