Page:EB1911 - Volume 21.djvu/591

only, the lower keyboard to the second unison. Releasing the

machine stop and quitting the pedal restores the first unison on

both keyboards and the octave on the lower. The right-hand

pedal was to raise a hinged portion of the top or cover and thus

gain some power of “swell” or crescendo, an invention of

Roger Plenius,[1] to whom also the harp stop may be rightly

attributed. This ingenious harpsichord maker had been

stimulated to gain these effects by the nascent pianoforte which,

as we shall find, he was the first to make in England. The first

idea of pedals for the harpsichord to act as stops appears to have

been John Hayward’s (?Haward) as early as 1676, as we learn

from Mace’s Musick’s Monument, p. 235. The French makers

preferred a kind of knee-pedal arrangement, known as the

“genouillère,” and sometimes a more complete muting by one

long strip of buff leather, the “sourdine.” As an improvement

upon Plenius’s clumsy swell, Shudi in 1769 patented the Venetian

swell, a framing of louvres, like a Venetian blind, which opened

by the movement of the pedal, and becoming in England a

favourite addition to harpsichords, was early transferred to the

organ, in which it replaced the rude “nag’s-head” swell. A

French harpsichord maker, Marius, whose name is remembered

from a futile attempt to design a pianoforte action, invented a

folding harpsichord, the “clavecin brisé,” by which the instrument

could be disposed of in a smaller space. One, which is

preserved at Berlin, probably formed part of the camp baggage

of Frederick the Great.

It was formerly a custom with kings, princes and nobles

to keep large collections of musical instruments for actual

playing purposes, in the domestic and festive music of their

courts. There are records of their inventories,

and it was to keep such a collection in playing order

that Prince Ferdinand dei Medici engaged a Paduan

Cristofori’s invention

of the Pianoforte.

harpsichord maker, Bartolommeo Cristofori, the

man of genius who invented and produced the pianoforte.[2]

We fortunately possess the record of this invention in a

literary form from a well-known writer, the Marchese Scipione

Maffei; his description appeared in the Giornale dei letterati

d’Italia, a publication conducted by Apostolo Zeno. The

date of Maffei’s paper was 1711. Rimbault reproduced it,

with a technically imperfect translation, in his History of the

Pianoforte. We learn from it that in 1709 Cristofori had

completed four “gravecembali col piano e forte”—keyed-psalteries

with soft and loud—three of them being of the long

or usual harpsichord form. A synonym in Italian for the

original cembalo (or psaltery) is “salterio,” and if it were struck

with hammers it became a “salterio tedesco” (the German

hackbrett, or chopping board), the latter being the common

dulcimer. Now the first notion of a pianoforte is a dulcimer

with keys, and we may perhaps not be wrong in supposing that

there had been many attempts and failures to put a keyboard

to a dulcimer or hammers to a harpsichord before Cristofori

successfully solved the problem. The sketch of his action in

Maffei’s essay shows an incomplete stage in the invention,

although the kernel of it—the principle of escapement or the

controlled rebound of the hammer—is already there. He obtains

it by a centred lever (linguetta mobile) or hopper, working, when

the key is depressed by the touch, in a small projection from

the centred hammer-butt. The return, governed by a spring,

must have been uncertain and incapable of further regulating

than could be obtained by modifying the strength of the spring.

Moreover, the hammer had each time to be raised the entire

distance of its fall. There are, however, two pianofortes by

Cristofori, dated respectively 1720 and 1726, which show a

much improved, we may even say a perfected, construction,

for the whole of an essential piano movement is there. The

earlier instrument (now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York)

has undergone considerable restoration, the original hollow

hammer-head having been replaced by a modern one, and the

hammer-butt, instead of being centred by means of the holes

provided by Cristofori himself for the purpose, having been

lengthened by a leather hinge screwed to the block;[3] but the

1726 one, which is in the Kraus Museum at Florence, retains

the original leather hammer-heads. Both instruments possess

alike a contrivance for determining the radius of the hopper,

and both have been unexpectedly found to have the “check”

(Ital. paramartello), which regulates the fall of the hammer

according to the strength of the blow which has impelled it to

the strings. After this discovery of the actual instruments of

Cristofori there can be no longer doubt as to the attribution of

the invention to him in its initiation and its practical completion

with escapement and check. To Cristofori we are indebted,

not only for the power of playing piano and forte, but for

the infinite variations of tone, or nuances, which render the

instrument so delightful.

|

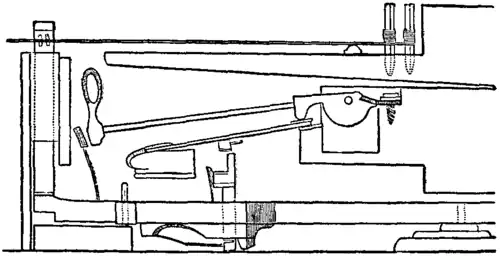

| Fig. 13.—Cristofori’s Escapement Action, 1720. Restored in 1875 by Cesare Ponsicchi. |

|

| Fig. 14.—Cristofori’s Piano e Forte, 1726; Kraus Museum, Florence. |

But his problem was not solved by the devising of a working action; there was much more to be done to instal the pianoforte as a new musical instrument. The resonance, that most subtle and yet all-embracing factor, had been experimentally developed to a certain perfection by many generations of spinet and harpsichord makers, but the resistance structure had to be thought out again. Thicker stringing, rendered indispensable to withstand even Cristofori’s light hammers, demanded in its turn a stronger framing than the harpsichord had needed. To make his structure firm he considerably increased the strength of the block which holds the tuning-pins, and as he could not do so without materially adding to its thickness, he adopted the bold expedient of inverting it; driving his wrest-pins, harp-fashion, through it, so that tuning was effected at their upper, while the wires were attached to their lower, ends. Then, to guarantee the security of the case, he ran an independent string-block round it of stouter wood than had been used in harpsichords, in which block the hitch-pins were driven to hold the farther ends of the strings, which were spaced at

- ↑ Mace describes a primitive swell contrivance for an organ 65 years before Plenius took out his patent (1741).

- ↑ The invention of the piano by Cristofori, and him alone, is now past discussion. What is still required to satisfy curiosity would be the discovery of a Fort Bien or Frederici square piano, said to antedate by a year or two Zumpe’s invention of the instrument in London. The name Fort Bien was derived, consciously or unconsciously, from the Saxon German peculiarity of interchanging B and P. Among Mozart’s effects at the time of his death was a Forte-Biano mit Pedal (see Vierzehnter jährlicher Bericht des Mozarteum, “Salzburg,” Dec. 19, 1791). Also wanted is the “old movement” for the long or grand pianos, sometimes quoted in the Broadwood day-books of the last quarter of the 18th century with reference to the displacement by the Backers English action.

- ↑ Communicated by Baron Alexander Kraus (May 1908).