Page:EB1911 - Volume 21.djvu/535

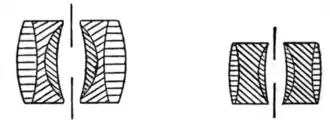

improvement was effected in the construction of non-distorting

objectives of fairly large aperture. It consisted of two positive

cemented flint menisci, each composed of a dense flint with negative

focus outside and a light flint with positive focus inside, its concave

surfaces facing the centre (fig. 26). This use of flint glasses alone

was peculiar, former achromatic lenses having been made of flint

and crown. These lenses were made in three rapidities: “Ordinary,”

𝑓/6 or 𝑓/7, angle 60°; “Landscape,” 𝑓/12 to 𝑓/15, angle 90°, also used

in convertible sets; “Wide Angle Landscape,” 𝑓/20 to 𝑓/25, angle

104°; “Wide Angle Reproduction,” similar to the last, but with

sharper definition. The “Aplanat” had many advantages over

previous doublets and the triplet, being more rapid, perfectly

symmetrical, so that there was no necessity for turning them when

enlarging, and free from distortion or flare There was no chemical

focus. Each component could be used alone for landscape work

with double focus, subject to the ordinary defects of single lenses.

By the use of Jena glasses in the “Universal Aplanat" (1886) the

components of this lens were brought closer together, its intensity

increased, and it was made more portable. J. H. Dallmeyer had

been working in the same direction simultaneously with Steinheil,

and in 1866 brought out his “Wide Angle Rectilinear,” 𝑓/15, angle

100°, made of flint and crown, the front element being larger than the

back (fig. 27). It was slow for ordinary purposes and was succeeded

in 1867 by the well-known “Rapid Rectilinear,” 𝑓/8, on the same

principle as Steinheil’s “Aplanat,” but made of flint and crown

(fig. 28). Ross’s “Rapid” and “Portable Symmetrical” lenses,

Voigtlander’s “Euryscopes,” and other similar lenses of British

and foreign manufacture are of the same type, and still in use.

Fig. 27.—Wide-Angle

Rectilinear Lens.Fig. 28.—Rapid Rectilinear Lens.

They are excellent for general purposes and copying, but astigmatism is always present, and although they can be used with larger apertures than the triplets they displaced, they require stopping down to secure good marginal definition over the size of plate they are said to cover. By the use of Jena glasses they have been improved to work at larger apertures, and some are made with triple cemented elements.

Fig. 29.—Triple Achromatic Lens.

4. Triple Combinations: Old Types.—This class comprises objectives

composed of three separate combinations of glasses widely separated

from each other. An early form of this type was made by Andrew

Ross (1841) for W. H. Fox Talbot, others by F. S. Archer, J. T.

Goddard (1859), T. Sutton (1860), but they never came into general

use. J. H. Dallmeyer’s “Triple

Achromatic Lens” (1861), 𝑓/10,

angle 60°, now out of date,

was an excellent non-distorting

lens, very useful for general

work and copying (fig. 29). As

made by Dallmeyer, the inner

surfaces of the front and back

components were slightly concave,

but in T. Ross’s “Actinic

Triplets” (1861), 𝑓/16, they were flat. The centre lens was an

achromatic negative serving to flatten the field.

5. Anastigmatic Combinations, Symmetrical and Unsymmetrical.—As already stated, it was found practically impossible to obtain flatness of field, together with freedom from astigmatism, in objectives constructed with the old optical glasses. A. Steinheil attempted it in the “Antiplanets,” but with only partial success. The Abbe and Schott Jena glasses, issued in 1886, put a new power into the hands of opticians by largely increasing their choice of glasses with different refractive and dispersive powers. Whereas the old glasses had high refractivity with higher dispersion, in the new ones high refractivity with lower dispersion could be set against lower refractivity with higher dispersion.

Fig. 30.—Con-

centric Lens.

Between 1887 and 1889 the first attempts to make anastigmatic

objectives with the new glasses were made by

M. Mittenzwei of Zwickau, R. D. Gray of New

Jersey, E. Hartnach and A Miethe of Berlin

(“Pantoscope”), K. Fritsch of Vienna (“Apochromat”)

and Fr. von Voigtlander of Brunswick,

with more or less success, but progress was hindered

by the instability of some of the early glasses,

which was afterwards overcome by sandwiching

the soft glasses between two hard ones. In 1888

Dr H. L. H. Schroeder worked out for Messrs Ross

the “Concentric Lens” (fig. 30) issued in 1892

(Ph. Jour., 16, p. 276). It was a symmetrical

doublet of novel construction, each element consisting

of a plano-convex crown of high refractivity

cemented to a plano-concave flint of lower

refractivity, but about equal or higher dispersion. Both the

uncemented surfaces were spherical and concentric. At 𝑓/16 it gave

sharp definition and flatness of field with freedom from astigmatism,

distortion or flare over an angle of 75°. It was an excellent

lens, though slow, and has been superseded by the “Homocentric”

and other more rapid anastigmats. Dr Paul Rudolph, of Messrs

Carl Zeiss & Co., Jena, worked out in 1889 a new and successful method

of constructing a photographic objective by which astigmatism of

the oblique rays and the want of marginal definition due to it could be

eliminated without loss of rapidity, so that a comparatively extended

field could be covered with a large aperture.

Fig. 31.—Anastigmat.

Series II. 𝑓/6·3.Fig. 32.—Anastigmat.

Series IIIa. 𝑓/9.

This he did on the principle of the opposite or opposed gradation of the refractive indices in the front and back lenses, by a combination of two dissimilar systems of single lenses cemented together, the positive element of each having in one case a higher and in the other a lower refractive index than that of the negative element with which it was associated. The front system, relied upon for the correction of spherical aberration, was made of the old glasses, a crown positive of low and a flint negative of high refractivity, whilst the back system, relied upon for the anastigmatic flattening of the field, was made of the new glasses, a crown positive of high and a flint negative of low refractivity, Both systems being spherically and chromatically corrected for a large aperture, the field was flattened, the astigmatism of the one being corrected by the opposite astigmatism of the other, without destroying the flatness of the field over a large angle (see E. Jb., 1891 and 1893; M. von Rohr’s Geschichte, and O. Lummer, Photographic Optics, for further details). They were issued by Messrs Zeiss and their licencees (in England, Messrs Ross), in 1890, in two different types. The more rapid had five lenses (fig. 31) two of ordinary glasses in the front normal achromat, and three in the back abnormal achromat, two crowns of very high refractive power with a negative flint of very low refractive power between them.

Fig. 33.—Anastigmat.

Series VI.Fig. 34.—Satz Anastigmat.

Series VIa.

The fifth lens assisted in removing spherical aberrations of higher orders with large apertures. The second type, series IIIa., 𝑓/9, 1899 (fig. 32), had only two lenses, the functions of which were as above. These combinations could not be used separately as single lenses. They are now issued as “Protars,” series IIa., 𝑓/8; IIIa., 𝑓/9; V., 𝑓/18. In 1891 Dr Rudolph devoted himself to perfecting the single landscape lens, and constructed on the same principle a single combination of three lenses, the central one having a refractive index between the indices of the two others, and one of its cemented surfaces diverging, while the other was converging. At 𝑓/14·5 this lens gave an anastigmatically flat image with freedom from spherical aberration on or off the axis. It was, however, not brought out till 1893, as a convertible lens or “Satz-Anastigmat,” series VI., 𝑓/14⋅5, and VIa., 𝑓/7·7 (figs. 33 and 34). In the meantime Dr E. von Hoegh (C. B. Goerz) and Dr A. Steinheil had also been working at the problem and had independently calculated lenses similar to Rudolph’s, but, whereas he had devoted himself to perfecting the single lens, they sought more perfect correction by combining two single anastigmatic lenses to form a doublet. Dr Rudolph had had the same idea, but Messrs Goerz secured the priority of patent in 1892, and in 1893 brought out their “Double Anastigmat,” now known as “Dagor.”

Fig. 35.

Ross-Goerz “Dagor.” Series III.Ross-Goerz. Series IV.

It was the first symmetrical anastigmat which combined freedom from astigmatism with flatness of field and great covering power at the large aperture of 𝑓/7·7 (fig. 35). Both these types of Zeiss’s “Protars” and Goerz’s “Dagor” anastigmats have since