In Anodonta these pallial tentacles are confined to a small area surrounding

the inferior siphonal notch (fig. 1 [3], t). When the edges

of the mantle ventral to the inhalant orifice are united, an anterior

aperture is left for the protrusion of the foot, and thus there are three

pallial apertures altogether, and species in this condition are called

“Tripora.” This is the usual condition in the Eulamellibranchia

and Septibranchia. When the pedal aperture is small and far

forward there may be a fourth aperture in the region of the fusion

behind the pedal aperture. This occurs in Solen, and such forms are

called “Quadrifora.”

|

|

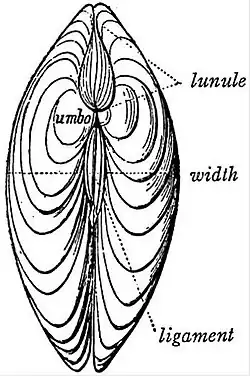

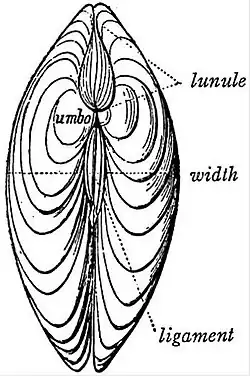

Fig. 2.—View of the two

Valves of the Shell of

Cytherea (one of the Sinupalliate

Isomya), from the

dorsal aspect.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3.—Right Valve of the same Shell from

the Outer Face.

|

|

The centro-dorsal point a of the animal of Anodonta (fig. 1 [1]) is

called the umbonal area; the great anterior muscular surface h is that

of the anterior adductor muscle, the

posterior similar surface i is that of

the posterior adductor muscle; the long

line of attachment u is the simple

“pallial muscle,”—a thickened ridge

which is seen to run parallel to the

margin of the mantle-skirt in this

Lamellibranch. In siphonate forms the

pallial muscle is not simple, but is indented

posteriorly by a sinus formed by

the muscles which retract the siphons.

It is the approximate equality in the

size of the anterior and posterior adductor

muscles which led to the name

Isomya for the group to which Anodonta

belongs. The hinder adductor muscle

is always large in Lamellibranchs, but

the anterior adductor may be very

small (Heteromya), or absent altogether

(Monomya). The anterior adductor

muscle is in front of the mouth and

alimentary tract altogether, and must

be regarded as a special and peculiar

development of the median anterior part

of the mantle-flap. The posterior adductor

is ventral and anterior to the

anus. The former classification based on these differences in the

adductor muscles is now abandoned, having proved to be an unnatural

one. A single family may include isomyarian, anisomyarian

and monomyarian forms, and the latter in development pass through

stages in which they resemble the first two. In fact all Lamellibranchs

begin with a condition in which there is only one adductor, and that

not the posterior but the anterior. This is called the protomonomyarian

stage. Then the posterior adductor develops, and becomes

equal to the anterior, and finally in some cases the anterior becomes

smaller or disappears. The single adductor muscle of the Monomya

is separated by a difference of fibre into two portions, but neither of

these can be regarded as possibly representing the anterior adductor

of the other Lamellibranchs. One of these portions is more ligamentous

and

serves to keep the

two shells constantly

attached

to one another,

whilst the more

fleshy portion

serves to close the

shell rapidly when

it has been gaping.

In removing the

valves of the shell

from an Anodonta,

it is necessary

not only to cut

through the muscular

attachments

of the body-wall

to the shell but to

sever also a strong

elastic ligament,

or spring resembling

india-rubber, joining the two shells about the umbonal area.

The shell of Anodonta does not present these parts in the most

strongly marked condition, and accordingly our figures (figs. 2, 3, 4)

represent the valves of the sinupalliate genus Cytherea. The corresponding

parts are recognizable in Anodonta. Referring to the figures

(2, 3) for an explanation of terms applicable to the parts of the valve

and the markings on its inner surface—corresponding to the muscular

areas already noted on the surface of the animal’s body—we must

specially note here the position of that denticulated thickening of the

dorsal margin of the valve which is called the hinge (fig. 4). By this

hinge one valve is closely fitted to the other. Below this hinge each

shell becomes concave, above it each shell rises a little to form the

umbo, and it is into this ridge-like upgrowth of each valve that the

elastic ligament or spring is fixed (fig. 4). As shown in the diagram

(fig. 5) representing a transverse section of the two valves of a

Lamellibranch, the two shells form a double lever, of which the

toothed-hinge is the fulcrum. The adductor muscles placed in the

concavity of the shells act upon the long arms of the lever at a

mechanical advantage; their contraction keeps the shells shut, and

stretches the ligament or spring h. On the other hand, the ligament

h acts upon the short arm formed by the umbonal ridge of the shells;

whenever the adductors relax, the elastic substance of the ligament

contracts, and the shells gape. It is on this account that the valves

of a dead Lamellibranch always gape; the elastic ligament is no

longer counteracted by the effort of the adductors. The state of

closure of the valves of the shell is not, therefore, one of rest; when

it is at rest—that is,

when there is no muscular

effort—the valves

of a Lamellibranch are

slightly gaping, and are

closed by the action of

the adductors when the

animal is disturbed. The

ligament is simple in

Anodonta; in many Lamellibranchs

it is separated

into two layers, an outer

and an inner (thicker and

denser). That the condition

of gaping of the

shell-valves is essential

to the life of the Lamellibranch

appears from the

fact that food to nourish

it, water to aerate its

blood, and spermatozoa

to fertilize its eggs, are

all introduced into this

gaping chamber by currents of water, set going by the highly-developed

ctenidia. The current of water enters into the sub-pallial

space at the spot marked e in fig. 1 (1), and, after passing as far forward

as the mouth w in fig. 1 (5), takes an outward course and

leaves the sub-pallial space by the upper notch d. These notches are

known in Anodonta as the afferent and efferent siphonal notches

respectively, and correspond to the long tube-like afferent inferior

and efferent superior “siphons” formed by the mantle in many

other Lamellibranchs (fig. 8).

|

|

Fig. 4.—Left Valve of the same Shell

from the Inner Face. (Figs. 2, 3, 4 from

Owen.)

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5.—Diagram

of a section of a

Lamellibranch’s

shells, ligament and

adductor muscle.

a, b, right and left

valves of the shell;

c, d, the umbones or

short arms of the

lever; e, f, the long

arms of the lever;

g, the hinge; h, the

ligament; i, the adductor

muscle.

|

|

Whilst the valves of the shell are equal in Anodonta we find in

many Lamellibranchs (Ostraea, Chama, Corbula, &c.) one valve

larger, and the other smaller and sometimes

flat, whilst the larger shell may be fixed to

rock or to stones (Ostraea, &c.). A further

variation consists in the development of

additional shelly plates upon the dorsal line

between the two large valves (Pholadidae). In

Pholas dactylus we find a pair of umbonal

plates, a dors-umbonal plate and a dorsal

plate. It is to be remembered that the whole

of the cuticular hard product produced on

the dorsal surface and on the mantle-flaps

is to be regarded as the “shell,” of which a

median band-like area, the ligament, usually

remains uncalcified, so as to result in the production

of two valves united by the elastic

ligament. But the shelly substance does not

always in boring forms adhere to this form

after its first growth. In Aspergillum the

whole of the tubular mantle area secretes a

continuous shelly tube, although in the young

condition two valves were present. These

are seen (fig. 7) set in the firm substance of

the adult tubular shell, which has even replaced

the ligament, so that the tube is

complete. In Teredo a similar tube is formed

as the animal elongates (boring in wood),

the original shell-valves not adhering to it

but remaining movable and provided with

a special muscular apparatus in place of a

ligament. In the shell of Lamellibranchs

three distinct layers can be distinguished:

an external chitinous, non-calcified layer, the

periostracum; a middle layer composed of

calcareous prisms perpendicular to the surface,

the prismatic layer; and an internal layer

composed of laminae parallel to the surface,

the nacreous layer. The last is secreted by the

whole surface of the mantle except the border, and additions to its

thickness continue to be made through life. The periostracum is

produced by the extreme edge of the mantle border, the prismatic

layer by the part of the border within the edge. These two layers,

therefore, when once formed cannot increase in thickness; as the

mantle grows in extent its border passes beyond the formed parts

of the two outer layers, and the latter are covered internally by a

deposit of nacreous matter. Special deposits of the nacreous matter

around foreign bodies form pearls, the foreign nucleus being usually

of parasitic origin (see Pearl).