form  , that is to say, the difference between the energy in two different states. The only cases, however, in which we have experimental values of this quantity are when the substance is either liquid and surrounded by similar liquid, or gaseous and surrounded by similar gas. It is impossible to make direct measurements of the properties of particles of the substance within the insensible distance ε of the bounding surface.

, that is to say, the difference between the energy in two different states. The only cases, however, in which we have experimental values of this quantity are when the substance is either liquid and surrounded by similar liquid, or gaseous and surrounded by similar gas. It is impossible to make direct measurements of the properties of particles of the substance within the insensible distance ε of the bounding surface.

When a liquid is in thermal and dynamical equilibrium with its vapour, then if  and

and  are the values of

are the values of  and

and  for the vapour, and

for the vapour, and  and

and  those for the liquid,

those for the liquid,

(21)

where  is the dynamical equivalent of heat,

is the dynamical equivalent of heat,  is the latent heat of unit of mass of the vapour, and

is the latent heat of unit of mass of the vapour, and  is the pressure. At points in the liquid very near its surface it is probable that

is the pressure. At points in the liquid very near its surface it is probable that  is greater than

is greater than  , and at points in the gas very near the surface of the liquid it is probable that

, and at points in the gas very near the surface of the liquid it is probable that  is less than

is less than  , but this has not as yet been ascertained experimentally. We shall therefore endeavour to apply to this subject the methods used in Thermodynamics, and where these fail us we shall have recourse to the hypotheses of molecular physics.

, but this has not as yet been ascertained experimentally. We shall therefore endeavour to apply to this subject the methods used in Thermodynamics, and where these fail us we shall have recourse to the hypotheses of molecular physics.

We have next to determine the value of  in terms of the action between one particle and another. Let us suppose that the force between two particles

in terms of the action between one particle and another. Let us suppose that the force between two particles  and

and  at the distance

at the distance  is

is

(22)

being reckoned positive when the force is attractive. The actual force between the particles arises in part from their mutual gravitation, which is inversely as the square of the distance. This force is expressed by  . It is easy to show that a force subject to this law would not account for capillary action. We shall, therefore, in what follows, consider only that part of the force which depends on

. It is easy to show that a force subject to this law would not account for capillary action. We shall, therefore, in what follows, consider only that part of the force which depends on  , where

, where  is a function of

is a function of  which is insensible for all sensible values of

which is insensible for all sensible values of  , but which becomes sensible and even enormously great when

, but which becomes sensible and even enormously great when  is exceedingly small.

is exceedingly small.

If we next introduce a new function of  and write

and write

(23)

then  will represent—(1) The work done by the attractive force on the particle

will represent—(1) The work done by the attractive force on the particle  , while it is brought from an infinite distance from

, while it is brought from an infinite distance from  to the distance

to the distance  from

from  ; or (2) The attraction of a particle

; or (2) The attraction of a particle  on a narrow straight rod resolved in the direction of the length of the rod, one extremity of the rod being at a distance

on a narrow straight rod resolved in the direction of the length of the rod, one extremity of the rod being at a distance  from

from  , and the other at an infinite distance, the mass of unit of length of the rod being

, and the other at an infinite distance, the mass of unit of length of the rod being  . The function

. The function  is also insensible for sensible values of

is also insensible for sensible values of  , but for insensible values of

, but for insensible values of  it may become sensible and even very great.

it may become sensible and even very great.

If we next write

(24)

then  will represent—(1) The work done by the attractive force while a particle

will represent—(1) The work done by the attractive force while a particle  is brought from an infinite distance to a distance

is brought from an infinite distance to a distance  from an infinitely thin stratum of the substance whose mass per unit of area is

from an infinitely thin stratum of the substance whose mass per unit of area is  ; (2) The attraction of a particle

; (2) The attraction of a particle  placed at a distance

placed at a distance  from the plane surface of an infinite solid whose density is

from the plane surface of an infinite solid whose density is  .

.

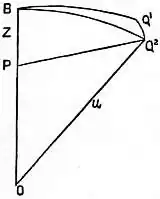

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Let us examine the case in which the particle  is placed at a distance

is placed at a distance  from a curved stratum of the substance, whose principal radii of curvature are

from a curved stratum of the substance, whose principal radii of curvature are  and

and  . Let

. Let  (fig. 2) be the particle and

(fig. 2) be the particle and  a normal to the surface. Let the plane of the paper be a normal section of the surface of the stratum at the point

a normal to the surface. Let the plane of the paper be a normal section of the surface of the stratum at the point  , making an angle

, making an angle  with the section whose radius of curvature is

with the section whose radius of curvature is  . Then if

. Then if  is the centre of curvature in the plane of the paper, and

is the centre of curvature in the plane of the paper, and  ,

,

(25)

Let  ,

,

(26)

The element of the stratum at Q may be expressed by

or expressing  in terms of

in terms of  by (26),

by (26),

Multiplying this by  and by

and by  , we obtain for the work done by the attraction of this element when

, we obtain for the work done by the attraction of this element when  is brought from an infinite distance to

is brought from an infinite distance to  ,

,

Integrating with respect to  from

from  to

to  , where a is a line very great compared with the extreme range of the molecular force, but very small compared with either of the radii of curvature, we obtain for the work

, where a is a line very great compared with the extreme range of the molecular force, but very small compared with either of the radii of curvature, we obtain for the work

and since  is an insensible quantity we may omit it. We may also write

is an insensible quantity we may omit it. We may also write

since  is very small compared with

is very small compared with  , and expressing

, and expressing  in terms of

in terms of  by (25), we find

by (25), we find

This then expresses the work done by the attractive forces when a particle  is brought from an infinite distance to the point

is brought from an infinite distance to the point  at a distance

at a distance  from a stratum whose surface-density is

from a stratum whose surface-density is  , and whose principal radii of curvature are

, and whose principal radii of curvature are  and

and  .

.

To find the work done when  is brought to the point

is brought to the point  in the neighbourhood of a solid body, the density of which is a function of the depth

in the neighbourhood of a solid body, the density of which is a function of the depth  below the surface, we have only to write instead of

below the surface, we have only to write instead of  , and to integrate

, and to integrate

where, in general, we must suppose  a function of

a function of  . This expression, when integrated, gives (1) the work done on a particle

. This expression, when integrated, gives (1) the work done on a particle  while it is brought from an infinite distance to the point

while it is brought from an infinite distance to the point  , or (2) the attraction on a long slender column normal to the surface and terminating at

, or (2) the attraction on a long slender column normal to the surface and terminating at  , the mass of unit of length of the column being

, the mass of unit of length of the column being  . In the form of the theory given by Laplace, the density of the liquid was supposed to be uniform. Hence if we write

. In the form of the theory given by Laplace, the density of the liquid was supposed to be uniform. Hence if we write

the pressure of a column of the fluid itself terminating at the surface will be

and the work done by the attractive forces when a particle  is brought to the surface of the fluid from an infinite distance will be

is brought to the surface of the fluid from an infinite distance will be

If we write

then  will express the work done by the attractive forces, while a particle

will express the work done by the attractive forces, while a particle  is brought from an infinite distance to a distance

is brought from an infinite distance to a distance  from the plane surface of a mass of the substance of density

from the plane surface of a mass of the substance of density  and infinitely thick. The function

and infinitely thick. The function  is insensible for all sensible values of

is insensible for all sensible values of  . For insensible values it may become sensible, but it must remain finite even when

. For insensible values it may become sensible, but it must remain finite even when  , in which case

, in which case  .

.

If  is the potential energy of unit of mass of the substance in vapour, then at a distance

is the potential energy of unit of mass of the substance in vapour, then at a distance  from the plane surface of the liquid

from the plane surface of the liquid

At the surface

At a distance  within the surface

within the surface

If the liquid forms a stratum of thickness c, then

The surface-density of this stratum is  . The energy per unit of area is

. The energy per unit of area is

Since the two sides of the stratum are similar the last two terms are equal, and

Differentiating with respect to  , we find

, we find

Hence the surface-tension

Integrating the first term within brackets by parts, it becomes

Remembering that  is a finite quantity, and that

is a finite quantity, and that  , we find

, we find

(27)

When  is greater than

is greater than  this is equivalent to

this is equivalent to  in the equation of Laplace. Hence the tension is the same for all films thicker than

in the equation of Laplace. Hence the tension is the same for all films thicker than  , the range of the molecular forces. For thinner films

, the range of the molecular forces. For thinner films

Hence if  is positive, the tension and the thickness will increase together. Now

is positive, the tension and the thickness will increase together. Now  represents the attraction between a particle

represents the attraction between a particle  and the plane surface of an infinite mass of the liquid, when the distance of the particle outside the surface is

and the plane surface of an infinite mass of the liquid, when the distance of the particle outside the surface is  . Now, the force between the particle and the liquid is certainly, on the whole, attractive; but if between any two small values of

. Now, the force between the particle and the liquid is certainly, on the whole, attractive; but if between any two small values of  it should be repulsive, then for films whose thickness lies between these values the tension will increase as the thickness diminishes, but for all other cases the tension will diminish as the thickness diminishes.

it should be repulsive, then for films whose thickness lies between these values the tension will increase as the thickness diminishes, but for all other cases the tension will diminish as the thickness diminishes.

We have given several examples in which the density is assumed to be uniform, because Poisson has asserted that capillary

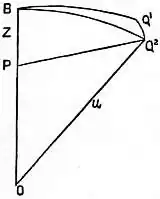

Fig. 2

Fig. 2