Page:Century Magazine v069 (centuryillustrat69holl).pdf/448

THE SCIENTIST AND THE MOTH

BY JENNETTE LEE

HE Scientist attended to the little crabs on his plate. If the truth must be told, he had not noted that they were crabs, or that they were canned. He was wondering which was Henrietta; and if she played the andante.

HE Scientist attended to the little crabs on his plate. If the truth must be told, he had not noted that they were crabs, or that they were canned. He was wondering which was Henrietta; and if she played the andante.

It was a Schubert andante, and he knew the violin score by heart. He had often played it in Germany; but he had not expected to find it here among the redwoods of California. He had been standing by the piano humming it absently to himself, before dinner, when they came in—gliding, floating, walking. The Scientist could not have told how they came. His sight was never very good at the best, and he had taken off his glasses and rubbed them on his handkerchief as they approached. He always did this at the advent of a new specimen. They had held out cordial hands to him—one, firm and hearty, like a boy's, he remembered now; the other, raised in a slow curve and seeking his gracefully. He could not recall which was which. This made him sorry.

For, as the dinner progressed, he perceived that Mrs. Tryon's two daughters were very different. The one that sat opposite her mother at the end of the table must be the elder, he decided, though age could hardly be associated with either of them. They were like wood-nymphs that had drifted in for a casual meal, catching their drapery as they came, and wearing it with modesty but not of necessity. These were unseemly and riotous thoughts for the brain of a scientist. How they came there I will not pretend to say. I can only mention that, although during thirty years' pursuit of bugs and moths he had lived almost constantly in the woods, the Scientist had never before encountered a wood-nymph or dreamed of one. To meet two at a first encounter was naturally somewhat embarrassing.

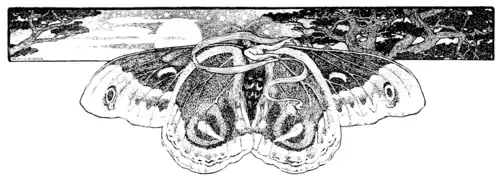

He took a safe moment to look again at the elder of the two. She was big and gentle, and the hair on her low forehead was of the softest brown. It occurred to the Scientist that one might like to touch it. His second thought was that it was the color of the moth he had come to find. He returned circumspectly to his crabs.

When he looked up again, the younger one, the one across the table from him, was regarding him frankly. She had clear, dark eyes, and her nose tilted a little, which kept her from being beautiful. But the eyes were very friendly—like a St. Bernard's, the Scientist decided, only nicer. He suddenly took courage and leaned forward.

"Do you play the andante?" he asked, motioning toward the open door.

She looked at him with wide eyes.

"I hate music," she said.

"Henrietta!" murmured her mother. "Not hate—you don't mean that you hate it."

The girl shook her head perversely.

"I do. I hate it."

Her mother looked at her helplessly for a minute. Then her face relaxed.

"She does n't hate it," she said confidingly; "she has n't, perhaps, Ethelberta's touch—"