Old Westland/Chapter 10

Chapter X

A. D. Dobson

Despite Howitt’s untimely end, the Canterbury Provincial Government intensified the work of cutting tracks and opening up the country around Lake Brunner; Drake, who was already in the district, taking over Howitt’s duties. (This early surveyor, his work completed in Westland, went north to Nelson, where, some years later, he too met his death by drowning.) The carrying out of these surveys necessarily meant the employment of several men, all of whom were keen prospectors, who, in bad weather, and during their leisure, did their utmost to locate gold, and thus gain the reward offered for the discovery of a payable field. Among those thus employed was a man named Albert William Hunt, a practical prospector, though a man of mystery who was destined to become, as this story will reveal, the stormy petrel of Old Westland, a veritable will-of-the-wisp, with an uncanny flair for finding the precious metal. Hunt, who has been described by many writers as an Australian, was as a matter of fact a New Zealander—the son of an Epsom publican, who spent his youth in Auckland. Coming down to the South Island about 1862, he first tried his luck on the Collingwood goldfields, where he obtained the experience necessary to qualify as a first-class prospector. He then set out to explore many parts of the Grey district, and when his funds were exhausted, he joined up, as mentioned, with Drake’s party, who were then engaged in cutting a track down the Hohonu River to its junction with the Taramakau. Hunt became very interested in this locality as a potential goldfield, and did a lot of prospecting in various places, getting very encouraging results, but failing for a time “to strike it rich.” Other prospectors, too, were impressed with the possibilities of the Hohonu district, paying particular attention to the Greenstone Creek. Here Maoris were also at work and were successful in getting the “colour” almost everywhere. The country, however, was very rough, and food hard to obtain, and this combination of circumstances brought about the temporary retirement of all the Europeans in the locality with the exception of Albert Hunt.

{nop}} Apart from the Provincial Government’s activities at and around Lake Brunner, they in June, 1863, invited tenders for the survey of the West Coast and intervening country, from the Grey River to the southern boundary of the province, and A. D. (afterwards Sir Arthur Dudley) Dobson was the successful tenderer. Proceeding from Port Cooper to Nelson for the purpose of chartering a small vessel to convey him to the Coast, he experienced no difficulty in so doing, and soon made the necessary arrangements with Thomas Askew, a merchant and shipowner, to transport his party, their supplies and equipment to the Grey River, the vessel to be used being the schooner Gipsy, Captain Jack McCann in command. The voyage was a very protracted one, and although the little schooner sailed on August 7th, and was actually off the Grey on the 30th of the same month, she did not try to enter until September 13th, having been blown to sea. Sir Arthur, in “Reminiscences,” thus describes this attempt, and the wreck of the Gipsy, the first to occur at Greymouth.

“On Sunday, September 13th, at high water we stood in to take the bar, with a light wind from the north-west. There was still a good roll on but it did not seem much until we began to approach the shore, some distance from which we found the rollers much heavier than we had anticipated, and our little schooner tossed about like a cork in the waves. The wind, failing somewhat, was insufficient to keep way on the ship and when we got into the breakers it was impossible to steer. We were all stripped to our flannels, ready to swim if necessary. We were now slowly drifting towards the shore, and I was holding on to the running rigging, near the main mast. Carefully watching the seas I noticed a huge wave coming towards us. As it neared the ship, it seemed to rise up into a thin narrow edge, almost transparent at the top and flecked with a little white spray. It rose like a wall high above the bulwarks, then curled over, and the ship was covered with a mass of broken water. The small whaleboat was well bolted down to the deck, with strong chains, between the two masts, keel upwards. The wave ran over the top of this without breaking the chains, but the galley was swept away and the bulwarks broken off level with the deck. We were all now hanging on for dear life. If I had had any certainty that I was going to get ashore safely there would have been some enjoyment in the situation, for it was a very grand sight to see each wave of broken water rushing over us and throwing the ship nearer the shore. It seemed a very long time as wave after wave pounded us, but we had ample time to get a good breath between each submergence, though we were getting badly bruised by being knocked against the deck and masts, as the seas went surging by.

“The heavy rains had caused a flood in the river, we soon getting into dirty water and a strong current, which carried us rapidly northwards. Then a heavier sea than usual threw us right against the mass of drift timber which at that time covered the beach down to high water mark. We were now safe, but still hung on until the ship steadied herself against the driftwood, then we dropped off the bowsprit on to the shore.

“A big dog belonging to one of our passengers had already got there and was waiting for his master. As the tide was falling the Gipsy was soon firmly stranded, so we went aboard and got our clothes, which were stowed in the cabin and quite dry.

“On the beach we found Charles Townsend, John Smith (cook) and Peter Mitchelmore (carpenter) who had charge of a depot which had been established to assist prospectors. Sherrin and Price and a number of Maoris from the pa, which was called Mawhera, were all waiting to render assistance. Counting the natives there must have been thirty men available, and with the help of these the stores were soon landed, and everything moveable placed above high water mark before night set in. The Gipsy was so badly damaged that it was found impossible to repair her and many years later the wreck was destroyed by fire.”

Sir Arthur at once proceeded to get his surveys under way, but being handicapped through not speaking Maori he decided to learn something of the language. With this object in view he engaged a half-caste named Reid as a survey hand, and thanks to his instruction, plus the aid of a new testament, in Maori, found at the pa, he soon gained sufficient knowledge to carry on, and to correctly ascertain the native names of the physical features of the country. Commencing the traverse of the Coast, all went well for some time, then, owing to the fact that no less than seven men were drowned in seven months, Dobson’s men became so disheartened that they decided to return to Christchurch, and implored him to accompany them before he too died the national death. This he refused to do, and putting the party in charge of a Maori guide sent them across the Alps, and so on to the Plains.

He then trained a number of Maoris, who, assured of regular payment and of plenty of good food and tobacco, were only too eager to give him all the assistance required. He carried on in this manner, making good progress, until early in 1864, when the natives, who had by this time a little money coming to them, made up their minds to visit Kaiapoi, in consequence of which he found himself without men and unable to proceed. He thereupon decided to cross the Alps to Christchurch, for the purpose of reporting progress to the Provincial Government, the trip over the divide being made without incident, and it was during this visit that he discovered the pass that to-day commemorates his name.

On receiving his report the Provincial Government expressed great satisfaction at the progress made, and his contract was considerably extended. He was also instructed, prior to returning to the West Coast, to make an examination of the country on the east side of the main range, and to ascertain if there was a pass out of the Waimakariri watershed into any valleys running westward.

After a few days in Christchurch, on March 8th to be exact, Dobson and his brother George set out for the Upper Waimakariri, where the latter was engaged in setting out roads; on the 10th Craigieburn was reached, and here George Dobson remained, A. D. Dobson being joined by another brother, Edward, with whom he went on to Mr. Goldney’s station, Grassmere.

Quoting again from “Reminiscences,” Sir Arthur thus describes the actual discovery of the pass: “The next day we rode over the saddle into the valley and up the river bed until we came to a large stream running into the Waimakariri from the north-west. There seemed to be low country at its head. We camped in this valley at a point beyond which we could not take the horses. Next morning we went up the stream as far as possible, and then through the bush at the side, cutting our way with billhooks. It was hard work and although we had very light swags, it took the greater part of the day to get out of the bush into the scrub, where we found we had arrived at a swampy valley, about a mile in length which had been the bed of a glacier. We pitched our tents in the scrub, and had a good meal, then went to the end of the flat, where we found the moraine, which had blocked the north end of this valley. The barometer registered about three thousand feet above sea level. This was evidently an available saddle, with very little difficulties on the east side; the heavy work would be on the west side where there was a very precipitous descent into a long narrow gorge, the head of the Otira River. The view was very beautiful looking up the forest-covered hillsides to the snow capped mountains on the north side of the Taramakau. The rata was in full bloom and its red blossoms made a brilliant contrast to the dark foliage of the birch trees. We found the descent from the moraine for the first five hundred feet exceedingly steep, but there was sufficient width in the valley to allow a zig-zag cutting to be made into the head of the gorge, beyond which a good deal of heavy rock cutting would be required to make a dray road. In this respect it much resembled the Hurunui Saddle, where the eastern approach is comparatively easy, and the western side drops suddenly. . . . . Returning to Christchurch, I made a sketch of the country I had been over, and handed it with a report to the Chief Surveyor. I did not name this pass, but when the gold diggings commenced on the West Coast a committee of business men offered a prize of £200 for anyone who could find a better or more suitable pass, and at the same time my brother George was sent out to examine every available pass between the watershed of the Taramakau, Waimakariri and Hurunui.

“He carefully examined the pass at the head of every valley, and reported that Arthur’s Pass was by far the most suitable for a direct road to the Coast; hence the name by which it has been known ever since.”

On April 6th, Dobson set out for the Coast again. He had engaged a new survey party consisting of four Europeans, and had also purchased two horses and a mule. During this crossing he made a survey of the south branch of the Hurunui, after the completion of which good progress was made, the Coast being reached on the 22nd, and transport being greatly facilitated by the presence of the horses, which were the first to arrive in Westland.

At the Grey, Dobson found John Rochfort who had built a hut there, and stayed with him over the weekend, thus obtaining a much required rest. A most methodical man, particular to a degree as to food supplies, and having boats or canoes built for all river work, Dobson was the one surveyor of Old Westland who took no chances, and in consequence had few difficulties, and no serious ones.

After some six years’ service, during which many important works were carried out, he was in April, 1869, appointed District Engineer on the Nelson-West Coast Goldfields, with headquarters at Westport. Two years later, in 1871, John Blackett, Provincial Engineer for Nelson, was appointed Chief Engineer to the General Government, and Dobson was promoted to be Provincial Engineer in his stead.

A few months afterwards, Henry Lewis, his father-in-law, who was Chief Surveyor for the Nelson Province, retired, and as the principal work of the survey department lay in the West Coast Goldfields, Dobson was invited to take over this position also, and on so doing was appointed Chief Surveyor. This dual appointment he held until 1875, when he resigned, being immediately appointed District Engineer attached to the Public Works Department. Three years later he again resigned for the purpose of joining his father in Christchurch, there then being more work than Dobson senior could cope with. Thus after fifteen years of good and faithful service, did this very distinguished pioneer sever his connection with the West Coast Goldfields.

The history of the Dobson family is irrefutably interwoven with the story of Old Westland, for apart from his own honourable connection, Sir Arthur’s father, Edward Dobson, was Engineer to the Canterbury Provincial Government when Westland was part of that province, and it was he who was responsible for the construction of the West Coast Road in 1866. In addition to this Sir Arthur’s ill-fated brother, George Dobson—a road engineer—was murdered on the southern bank of the Grey River by the infamous Burgess-Sullivan gang of bushrangers, when in the execution of his duty.

Sir Arthur himself crossed the last divide on March 5th, 1934. He had attained the great age of 92 years. He was buried at the Linwood Cemetery, Christchurch. A “Canterbury Pilgrim,” having arrived by the Cressy, one of the First Four Ships, he had been described as a “veteran path finder.” A fitting tribute to a man who blazed the trail for us of to-day.

In recognition of his pioneering work a memorial obelisk has been erected on the summit of Arthur’s Pass, Standing on a knoll a few feet from the main highway, the obelisk, which is constructed of stone, bears a bronze tablet with the name Arthur Dudley Dobson in relief. Simplicity of design is the keynote, yet the impression it conveys is deep and lasting, proclaiming as it does, to all mankind, the heartfelt appreciation of the people of Canterbury and Westland for the pioneer who discovered, three-quarters of a century ago, the connecting link between the two provinces.

Recapitulating, it will be remembered that a whaleboat had been left on the beach some twenty miles south of the Grey. This Charles Townsend was most anxious to recover, and on October 7th, 1863, accompanied by Peter Mitchelmore and the Maori, Solomon, he proceeded down the coast for the purpose of bringing the boat to the Grey. En route he obtained the services of two other natives. On arrival they found the boat in good trim and the following day successfully launched it, and favoured with a fair wind sailed up the coast without mishap. When attempting to cross the bar, however, they were capsized in the breakers and Townsend, Mitchelmore and Solomon were drowned. The bodies of the two former were washed ashore, but that of Solomon was never found. Townsend and Mitchelmore lie side by side in the Karoro Cemetery, Greymouth. This is the first recorded fatality in attempting to work the Grey bar. Thus seven men had been drowned in seven months—all being Government servants. They were: Henry Whitcombe, Charlton Howitt and two others, Charles Townsend, Peter Mitchelmore and the Maori, Solomon. On the day following this tragedy the prospector Sherrin left for Christchurch to report the death of Townsend to the Provincial Government, J. Smith, the cook of the party, taking charge of the depôt. Five weeks later, November 14th, Sherrin again

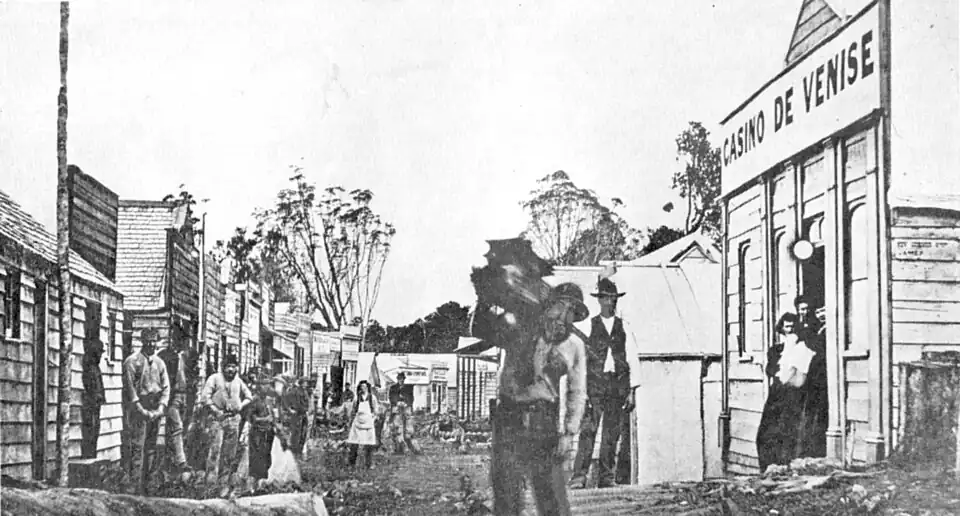

Napoleon Hill, Ahaura, Westland. A typical mining town of the mid sixties. Note the Casino De Venise, with dancing girls in doorway.

Ross, a notable field, made famous by the fact that in 2 years Cassius and Party won 22,000 ounces of gold.

The remainder of the year 1863 passed without incident. The surveys which were being made were gradually opening up the country, while the prospectors, thanks to the food supplies obtainable at the depot, were making the most of the long summer days in their unceasing search for the metal royal.