November Joe/Chapter 9

Chapter IX

The Looted Island

It was a clear night, bright with stars. Joe and I were sitting by our camp-fire near one of the fjords of western Alaska, where we had gone on a hunting expedition after the great moose of the West.

I was talking, when suddenly Joe touched me.

"Shsh!" he whispered. "There's some feller moving down by the creek."

"Impossible!" I said. "Why, we're a hundred miles from—"

"He's coming this way." Joe rose and motioned me back among the shadows. "There's some queer folk round here, I guess. Best be taking no chances."

We waited, and I was soon aware of a figure advancing through the night.

Then a voice said, "Fine night, mates," and a sinewy, long-armed fellow, with a bushy red beard, stepped into the circle of light.

"The cold makes you keep your hands in your pockets, don't it?" said Joe gently. "It does me."

I then noticed that both men were covering each other with revolvers through their pockets. The stranger slowly drew out his hand.

"Let's talk," said he sourly. "Who are you?"

"Give us a lead," said Joe.

"I'm John Stafford."

"This here is Mr. Quaritch, of Quebec. I'm his guide. We're come after big game."

Stafford looked round the camp with a shrewd eye.

"I guess you're speaking truth. It's up to me to apologize," he said.

He held out his hand, which November Joe and I shook with gravity.

"I'm free to own I was doubtful about you," he said. "You'll understand that when I tell you what's happened."

"Huh!" said Joe. "Sit down. There's tea in the kettle."

Stafford helped himself.

"Perhaps," he said at length, "you've

Both Men were covering each other with Revolvers noticed an island about eight miles off the coast, lying nor'-nor'-west?"

"Sort of loaf-shaped island? Yes."

"That's where I come from—Eel Island. I have a fox farm there. I returned to it yesterday after a run down to Valdez. When I went away a fortnight ago, I left my man in charge of some of the finest black foxes between this and Ungava. I got back to find the foxes all killed and my hired man gone—disappeared."

"Who was he?"

"An Aleut, called Sam. He's been in my employ three years. I see what you're thinking—that he killed the foxes, and I'd have thought that myself, only I know he did n't."

"How's that?"

"One reason is that I own only one boat, and when I went to the mainland last Friday week I took it, leaving Sam on the island. It's all of seven miles from the coast, so he could n't have got away if he wanted. That, I say, is one reason why it could n't have been him. The other reason's as good. I was decoyed away so cleverly. Here's the letter that did it."

The fox-farmer drew out a crumpled sheet of ruled paper from his pocket and handed it to me.

I read aloud:—

Sir,—Your wife wants you to come down at once. She's due for an operation in the hospital here on Friday week, and she's hard put to it to plan for the children till she gets about again. So you'd best come.

Yours truly,

S. Macfarlane,

(Doctor).

I gave him back the letter. "Any man would have gone on such news," I said.

"Well, I did," said Stafford savagely, "but it was a bad bit o' work. I got that letter twelve days back, and off I went hot-foot, leaving Aleut Sam in charge. It took me a week going down. When I reached the house where my wife is living, she was surprised to see me, and I showed her the letter. . . . You can guess. . . . It was all a plant! There was n't any Dr. Macfarlane, nor any operation. You might have struck me down when I heard that, but it was n't long before I dropped to the game, and back I came—record-breaking travel—to Eel Island. . . . I found the place clean gutted. All the blacks and silvers caught and killed, and the skinned carcasses lying around. And Aleut Sam vanished as if he had never lived."

"Have you a notion who done it?" inquired November.

Stafford ground his teeth. "It may have been done for spite, but whoever he was he lived in my cabin several days, and slept in my bunk. . . . I wonder what he did with Sam. Knocked him on the head and heaved him in the sea like as not."

Joe nodded.

Stafford continued: "I could tell he had n't been long gone, and so when I saw the smoke of your camp-fire, I got the skiff and came over. I thought it might be the chap that raided my farm. That's why I walked up with my revolver in my fist. . . . I'm nigh desperate. The work of three years gone . . . three winters spent with Sam alone, like some kind of a Crusoe and his man Friday . . . and keeping my wife and two little gals down at Valdez . . ."

"Look here, ain't it a bit early in the year to kill foxes?" said Joe, after a pause.

"They'd have been worth twenty-five per cent more in a month."

"Then why . . .?"

"Because I could n't have been decoyed away except while the steamer was running before the winter closed down. See?"

"O' course," said Joe. "And you think some one done it for spite?"

Stafford bent nearer.

"This dirty business may have been done as much for gain as spite. Even as early as this in the year the pelts were worth fifteen thousand dollars."

"My!" said Joe. "Suspect any one in particular?"

"I believe it may have been Trapper Simpson. He's had a down on me this good while back. Well, if it was him, he's paid me out good, the blackguard . . . the . . ."

"Hard words don't bring down nor man nor deer," said Joe.

There was a silence; then I said:—

"What would you give the man that discovered who it was robbed you?"

"If he did n't get me back my pelts, I could give him nothing. If he did, he'd be welcome to five hundred dollars," replied the fox-farmer.

"Good enough, November?" I asked.

Joe nodded.

"What do you mean?" asked Stafford, turning to Joe. "You a trail-reader?"

"Learnin' to be," said Joe.

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

Thus it was agreed that we should go across to Eel Island at dawn to let November have a look round. I could see that Stafford had no great belief in the chances of Joe's success—which was not unnatural seeing that he knew nothing of November's powers.

We were away in good time. There was only a glimmer in the east when we got aboard the fox-farmer's skiff, and soon we were crossing the bar of the estuary. Just as we passed beyond it, Eel Island showed through the morning mists. As we approached, I saw that it was a barren atoll without any sign of human tenant. We made a good passage, and in due time, with our visitor at the tiller and November at the mainsheet, we ran into a poor anchorage.

We went ashore, and Joe at once took a cast, looking for tracks, though he knew he was little likely to find any, for the ground was as hard as iron and had been impervious for days. This was a state of affairs which particularly interested me, since hitherto most of Joe's successes that I had witnessed had owed a good deal to the reading of trails. In the present case this seemed impossible, for the frost had held from before the date of the crime.

We next climbed to Stafford's cabin. It proved to be built of wood with a felt roof, and the structure crouched in the lee of a gigantic boulder on the one side, and of the shoulder of a ridge on the other.

The owner threw open the door.

"Come right in," said he.

"Wait!" said Joe. "You told us the robber lived in here while he was on the island. If things is the way he left them, I'd like to look round."

"Have your way," said Stafford. "I have n't disturbed them. I put off directly I saw your smoke, and I had n't been long ashore."

Joe went in and made a rapid examination of the cabin. It was a tiny place furnished only with a rough deal table, a chair cut from a barrel, and the usual shallow wooden tray for a bunk. The walls were decorated with smaller shelves on which were heaped provisions, a few books, cooking-pots, knives, forks, and plates, all helter-skelter.

November examined everything with his usual swift care. He lit match after match and peered about the stove, for the interior of the cabin was pretty dark even in the daytime.

After this he bent over the table and, drawing his knife, scratched at a stain on the near side, and then at a similar stain upon the other.

"I'm through," he said at length.

Stafford, who had been watching Joe's proceedings with an air of incredulity that bordered on derision, now stepped forward and cast his eyes rapidly over every spot where Joe had paused, then turned sharply to question him:—

"Found out anything?"

"Not much," answered Joe.

"Well, all I can see is that the villain has eaten a good share of my grub."

"I dare say," said Joe. "There was two of them, you know . . ."

"No, I don't! And what else can you tell me about them?"

"I think they was man and wife. She's a smallish woman; I'd guess she's maybe weakly, too. And he's fond of reading; anyway, he can read."

Stafford stared at November half suspiciously.

"What?" he shouted. "Are you kidding me? Or how did you get all that?"

"That's easy," replied November. "There are two or three traces of a little flat foot in front of the stove, and a woman could n't run this job on her own, so it's likely there was a man, too."

Stafford grunted. "You said she was weakly!"

"I thought maybe she was, for if she had n't spilt the water out of the kettle most times she took it off the stove there would n't be any track, and here is one near on top of the other, so it happened more'n once on the same spot. She found your kettle heavy, Mr. Stafford," Joe said seriously.

"I'm free to own that seems sense," acknowledged Stafford. "But the reading—that's different."

"Table's been pulled up alongside the bunk, see that scrape of the leg; and he's had the lamp close up alongside near the edge where the stain is. There's plenty old oilstains in the middle of the table, but these close to the edges ain't been long on—you can see that for yourself."

"By Jingo!" said the fox-farmer. "Anything else?"

"The chap what robbed you was a trapper all right, and had killed a red fox recent, so recent he carried it across and skinned it here."

"Where?"

"By your stove." Joe bent down and picked up some short, red hairs. "Clumsy skinning!" said he. "Let's go out and take a look round the island."

Stafford led the way. At a short distance some of the skinned carcasses lay. They were blackened by the weather, and lay open to the sky, looking as horrible as skinned carcasses always will. Joe turned them over. Suddenly he bent down with that quick intentness that I had learnt to connect with his more important discoveries. From one he passed to another, till he had handled every carcass.

"What is it?" asked Stafford, whose respect for Joe was visibly increasing with each moment.

November straightened his back. "I'm sure it were n't done for spite," he remarked.

"What do you mean?"

But Joe would say nothing more. So we passed on, climbing all over the island. Stafford pointed out another lying some five miles north where he told us he kept his less valuable stock.

"There's a lot of red and cross foxes over there on Edith Island (it's named for my eldest gal)," he said. "Whenever there happens a black one in the litters I try to catch it, and bring it over here to Eel— Hullo! What's that?"

Stafford stood with his hands shading his eyes, staring at Edith Island.

"Look! That's smoke or I'm dreaming," he cried.

A very faint line of bluish haze rose from the distant rock.

"Smoke it is," said Joe.

"But the island is uninhabited. Come on! Come on!" cried Stafford excitedly. "It may be those ruffians clearing out Edith Island, too. We'll get after them!"

"All right, Mr. Stafford," agreed Joe. "But, look here, it may be those chaps that robbed you, but I don't want you to run up against disappointment. I guess it's liable to be your Aleut Sam marooned over there."

"Why?"

"That's a signal fire. Whoever's made that fire is putting on moss. And I've noticed things here that make me think it ain't likely they killed Sam."

"Let's get after them, anyway," cried Stafford. "If it's Sam, he'll be able to help us with his story."

It was not long before we were once more in the boat and tacking across towards Edith Island. As we drew nearer the volume of smoke grew thicker.

"It's sure a signal smoke," said Joe. "The feller's putting on wet moss."

The wind served us fairly well, and, as we ran under the lee of the land, we were aware of a figure standing on the beach waiting for us.

"It's Aleut Sam, sure enough," said Stafford.

The Aleut proved to be a squat fellow of a most Mongolian cast of countenance. A few score of long hairs, distinct, thick, and black, made up his mustache. His beard was even scantier, and a tight cap of red wool which he wore showed off the umber tint of his large round face.

We rowed ashore in the canvas boat, and on the beach Stafford held a rapid conversation with his man in Indian. Neither Joe nor I could follow what was said, but presently Stafford enlightened us.

"Sam says that one night, four days after I left Eel Island, he had just eaten his supper when he heard a knocking on the door. Thinking it must be me who had returned, he opened it. Seeing no one, he stepped out into the dark, when a pair of arms were thrown round him, and a cloth that smelt like the stuff that made him go asleep in the hospital (Sam's had most of his toes off on account of frost-bite down to Valdez) was clapped about his head. He struggled, and the next thing he knew he felt very sick, and when he came to, he found himself tied up and lying in the bottom of a boat at sea. He could tell there were two men with him. He thinks he was about half an hour conscious, when one of them, with his face muffled, stopped sculling, and knelt on his chest and put the sweet-smelling cloth over his head a second time. After that he does not remember any more until he woke up on the beach here. It was still dark, and the men and boat were gone. He was very sick again, and for all that night and most of the next day he thought he was going to die.

"Towards evening he began to feel better, and, wandering about, discovered a barrel of dried fish which had been tumbled ashore from the boat which marooned him—to keep him from starving, I suppose. He went up into the scrub and made a fire. Since then he's been here and seen no one. That's all."

"Then he did n't ever really see the faces of the chaps that kidnapped him?"

Stafford translated the question to Sam and repeated the answer.

"One had a beard and was a big man; he wore a peaked cap. Anything else to ask him?"

"Yes. How long has he been here on this island?"

"Eight days."

"What's he been doing all the time?"

"Just wandering around."

"Where has he been camped?"

Stafford raised his thumb over his shoulder. "In the scrub above here."

Joe nodded. "Well, let's go to his camping-place and boil the kettle. He'll sure have a bit of fire there."

So we made our way up through the scrub, filling the kettle from a little spring on the way as the Aleut led us to his bivouac. While I looked about it, I wondered once more at the skill of the men of the wilderness.

A rough breakwind masked the fire, and above the sleeping-place the boughs of dwarf willow and spruce were interlaced in cunning fashion.

Joe stirred the smouldering logs into life, but in doing so was so unfortunate as to overturn the kettle.

"That's bad," said he. "Best tell your man to get some more water."

Stafford sent off Sam on his errand; but no sooner had the Aleut disappeared than November was on his knees examining the charred embers and delving among the ashes.

It was easy to see that he was hot on some scent, though what on earth it could be neither Stafford nor I had any notion. After some busy moments he drew back.

"Get rid of your hired man for a while longer, only so he don't suspect anything," he said. "I hear him coming."

"You mean he's in the robbery?"

"He sure is. And, what's more, it looks to me like he's your only chance of getting your foxes back. Here he comes."

A moment later Sam appeared in sight walking up the narrow track between the rocks, kettle in hand. Stafford spoke to him in Aleut. Sam grunted in acquiescence, and went off up the hill that formed the centre of the island.

"I told him to go gather some more wood while the kettle's boiling. Now you can talk and tell me who you think has the pelts of my foxes."

"No one has n't," replied Joe.

"What!"

"Your foxes ain't dead."

"Ain't dead? You've forgot their skinned carcasses!"

"I allow we saw some skinned carcasses, but they was the carcasses of red foxes worth no more than ten dollars apiece instead of a thousand."

"But—"

"I know you took it for sure they was your foxes—and you're a fox-farmer, and ought to know. But I examined those carcasses mighty careful. Their eyes was n't the right colour for black foxes. That's one thing. For another, I found some red hairs. It ain't in nature you can take a pelt off and not a hair stick on the body under."

Stafford digested this in silence.

"But why in creation should the chaps have taken the trouble to bring over red fox carcasses?" he inquired at length.

"That's easy answered. They was after your best for stock. It's pretty likely they did n't take them far, and they would n't want you nosing about for your live foxes."

"Is that it?"

"Another thing, the robbers was six days or more on Eel Island. Now, they could catch and kill all your foxes in two. But to catch them so they would n't be hurt would take time. No, your foxes ain't dead yet; and they ain't far off, neither, and your Aleut knows who's got them."

"Why are you so sure about him being in it?"

"He told you he'd been eight days on this island, did n't he?"

Stafford nodded. "Eight days, that's what he said."

"He lied. I knew it the moment I set eyes on his fire."

Stafford frowned down at the singing kettle.

Joe continued:—

"Not enough ash to this fire to make heat to keep a man without a blanket comfortable for eight days this weather. And look! the boughs he's broke off for his bed. They're too fresh. Ag'in, he ain't got no axe here, yet the charred ends of the thicker bits on the fire has been cut with an axe. It's clear as light. The robbers ferried Sam across here about two days back, cut some wood for him so he should n't be too cold, gave him grub to last till 'bout the time you'd likely be home, and left him."

"I guess you're right. I see it now. I'm grateful to you."

Joe shook his head. "Keep that a bit till we've got your foxes back; and it looks to me like it might be a difficult proposition to prove who done it, unless o' course we could persuade Sam—"

"I'll persuade him. There he is coming over the hill."

"I wonder if your Sam is a fighter?" said Joe. "Anyway, best not be too venturesome. He's got a knife."

Stafford reached for his rifle, but Joe intervened.

"Stay you still and I'll show you the way we do in the lumber-camps."

Sam's strong, squat figure advanced towards us. As he stooped to throw the wood he had brought on the ground, Joe caught his shoulder with one hand and snatched the knife from his belt with the other. And then there flashed across the features of the Aleut an expression like a mad dog's; he flung himself gnashing and snarling on November.

But he was in the grip of a man too strong for him, and, though he returned again and again to the attack, the huge young woodsman twisted him to earth, where Stafford and I tied his struggling limbs.

This done, we rolled him over.

"Now," said Stafford, "who is it has got my foxes?"

The Aleut shook his head.

Stafford pulled out his revolver, opened the breech, made sure it was loaded, and cocked it. Next he held his watch in front of Sam's face and pointed out the fact that it wanted but five minutes to the hour.

"I'm telling him if he don't confess," he said, "I'll shoot him when the hand reaches the hour." He turned to us: "You'd best go."

"Good Heavens! you don't really mean—" I cried.

Stafford winked. Joe and I went down to the beach below.

A quarter of an hour passed before Stafford joined us.

"What's happened?" I asked.

"He's confessed all right." Then Stafford looked at Joe. "It all went through just the way you said. It was a rival fox-farmer, Jurgensen, did it. Landed on Eel Island with his wife the night I left, they were there until two days ago; took them all their time, and Sam's, to get my foxes. Then they brought him over here. Yes, Mr. Joe, you've been right from start to finish."

"What's going to be done next?"

"There's two courses. One is to put things in the hands of the police; the other is to sail right along with this wind to Upsala Island, where the Jurgensens live. But I can't go there alone. It's a nasty sort of business, you see, and one that should n't be carried through without witnesses, and I feel I've cut a big slice out of your hunting already."

"I don't know what Mr. Quaritch thinks," said Joe, "but perhaps he'd like to be in at the finish."

"Of course," said I.

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

And now I will leave out any account of the

If he don't confess, I'll shoot him events of the next sixteen hours, which we spent in the skiff, and pick up the thread of this history again with Stafford knocking at the door of the Jurgensens' cabin on Upsala Island. We had landed there after dark.

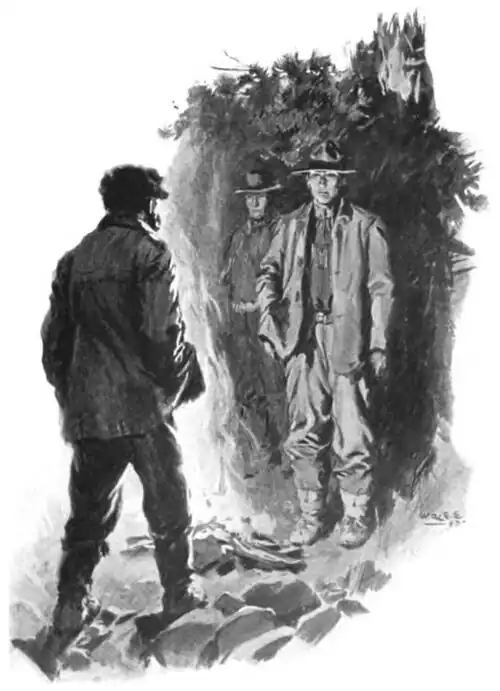

Joe and I stood back while Stafford faced the door. It was thrown open, and a big, ginger-bearded Swede demanded his business.

"I've just called around to take back my foxes," said Stafford.

"Vot voxes?"

"The blacks and silvers you stole."

"You are madt!"

"Shut it!" cried Stafford. "Ten days ago you and your wife, having decoyed me away to Valdez, went to Eel Island. You were there eight days, during which time you cleaned out every animal I owned on it. I know you did n't kill them, though you tried to make me believe you had by leaving the skinned carcasses of a lot of red foxes. Three days ago you left Eel Island . . ."

As he spoke I saw the wizened figure of a woman squeezing out under the big Swede's elbow.

She had a narrow face with blinking, malevolent eyes, that she fixed on Stafford.

"Zo! Vot then?" jeered Jurgensen.

"Then you rowed over to Edith Island and marooned my man, Aleut Sam, who was in the robbery with you."

The big Swede snatched up a rifle by the door and stepped out.

"Get out of here," he cried, "or—" He paused on catching sight of Joe and myself.

"I'll go if you wish it," said Stafford dangerously. "But if I do it'll be to return with the police."

"And look here, Mr. Dutchman," broke in Joe gently, "if it comes to that you'll get put away for a fifteen years' rest cure, sure."

"Who are you?" bellowed Jurgensen.

"He's the man that told me your wife was weakly and spilled the water from the kettle when she lifted it, for he found her tracks at my place by the stove. He's the man that discovered axe-cut log-ends in Aleut Sam's fire on Edith Island, when we knew Sam had no axe with him. He's the man I owe a lot to."

"Me alzo," said Jurgensen venomously as he bowed his head. "Vot you vant—your terms?" he asked at last.

Stafford had his answer ready. "My own foxes—that's restoration, and two of yours by way of interest―that's retribution."

"Ant if I say no?"

"You won't. Where's my foxes?"

Jurgensen hesitated, but clearly there could be only one decision in the circumstances. "I haf them in my kennels," he answered.

"Wire enclosures?" cried Stafford in disgust.

"Yess."

"You can't grow a decent pelt in a cage," snapped Stafford, with the eagerness of a fanatic mounted upon his hobby. "You must let them live their natural life as near as possible or their colour suffers. The pigmentary glands get affected—"

"Poof! I haf read of all that in the book, 'Zientific Zelection of Colour Forms.'"

"Yes," put in Joe. "You read a good bit while you were at Mr. Stafford's place, that's so? Lying in Mr. Stafford's bunk?"

Jurgensen raised startled eyes. "You see me?"

"No."

"How you know, then?"

Joe laughed. "I guess the spiders must 'a' told me," said he.