November Joe/Chapter 8

Chapter VIII

The Hundred Thousand Dollar Robbery

"I want the whole affair kept unofficial and secret," said Harris, the bank manager.

November Joe nodded. He was seated on the extreme edge of a chair in the manager's private office, looking curiously out of place in that prim, richly furnished room.

"The truth is," continued Harris, "we bankers cannot afford to have our customers' minds unsettled. There are, as you know, Joe, numbers of small depositors, especially in the rural districts, who would be scared out of their seven senses if they knew that this infernal Cecil James Atterson had made off with a hundred thousand dollars. They'd never trust us again."

"A hundred thousand dollars is a wonderful lot of money," agreed Joe.

"Our reserve is over twenty millions, two hundred times a hundred thousand," replied Harris grandiloquently.

Joe smiled in his pensive manner. "That so? Then I guess the bank won't be hurt if Atterson escapes," said he.

"I shall be bitterly disappointed if you permit him to do so," returned Harris. "But here, let's get down to business."

On the previous night, Harris, the manager of the Quebec Branch of the Grand Banks of Canada, had rung me up to borrow November Joe, who was at the time building a log camp for me on one of my properties. I sent Joe a telegram, with the result that within five hours of its receipt he had walked the twenty miles into Quebec, and was now with me at the bank ready to hear Harris's account of the robbery.

The manager cleared his throat and began with a question:—

"Have you ever seen Atterson?"

"No."

"I thought you might have. He always spends his vacations in the woods—fishing, usually. The last two years he has fished Red River. This is what happened. On Saturday I told him to go down to the strong-room to fetch up a fresh batch of dollar and five-dollar bills, as we were short. It happened that in the same safe there was a number of bearer securities. Atterson soon brought me the notes I had sent him for with the keys. That was about noon on Saturday. We closed at one o'clock. Yesterday, Monday, Atterson did not turn up. At first I thought nothing of it, but when it came to afternoon, and he had neither appeared nor sent any reason for his absence, I began to smell a rat. I went down to the strong-room and found that over one hundred thousand dollars in notes and bearer securities were missing.

"I communicated at once with the police and they started to make inquiries. I must tell you that Atterson lived in a boarding-house behind the Frontenac. No one had seen him on Sunday, but on Saturday night a fellow-boarder, called Collings, reports Atterson as going to his room about 10.30. He was the last person who saw him. Atterson spoke to him and said he was off to spend Sunday on the south shore. From that moment Atterson has vanished."

"Didn't the police find out anything further?" inquired Joe.

"Well, we could n't trace him at any of the railway stations."

"I s'pose they wired to every other police-station within a hundred miles?"

"They did, and that is what brought you into it."

"Why?"

"The constable at Roberville replied that a man answering to the description of Atterson was seen by a farmer walking along the Stoneham road, and heading north, on Sunday morning, early."

"No more facts?"

"No."

"Then let's get back to the robbery. Why are you so plumb sure Atterson done it?"

"The notes and securities were there on Saturday morning."

"How do you know?"

"It's my business to know. I saw them myself."

"Huh! . . . And no one else went down to the strong-room?"

"Only Atterson. The second clerk—it is a rule that no employee may visit the strong-room alone—remained at the head of the stairs, while Atterson descended."

"Who keeps the key?"

"I do."

"And it was never out of your possession?"

"Never."

November was silent for a few moments.

"How long has Atterson been with the bank?"

"Two years odd."

"Anything ag'in' him before?"

"Nothing."

At this point a clerk knocked at the door and, entering, brought in some letters. Harris stiffened as he noticed the writing on one of them. He cut it open and, when the clerk was gone out, he read aloud:—

Dear Harris,——

I hereby resign my splendid and lucrative position in the Grand Banks of Canada. It is a dog's dirty life; anyway it is so for a man of spirit. You can give the week's screw that's owing to me to buy milk and bath buns for the next meeting of directors.

Yours truly,

C. J. Atterson.

"What's the postmark?" asked Joe.

"Rimouski. Sunday, 9.30 a.m."

"It looks like Atterson's the thief," remarked Joe.

"I've always been sure of it!" cried Harris.

"I was n't," said Joe.

"Are you sure of it now?"

"I'm inclined that way because Atterson had that letter posted by a con—con—what's the word?"

"Confederate?"

"You've got it. He was seen here in town on Saturday at 10.30, and he could n't have posted no letter in Rimouski in time for the 9.30 a.m. on Sunday unless he'd gone there on the 7 o'clock express on Saturday evening. Yes, Atterson's the thief, all right. And if that really was he they saw Stoneham ways, he's had time to get thirty miles of bush between us and him, and he can go right on till he's on the Labrador. I doubt you'll see your hundred thousand dollars again, Mr. Harris."

"Bah! You can trail him easily enough?"

Joe shook his head. "If you was to put me on his tracks I could," said he, "but up there in the Laurentides he'll sure pinch a canoe and make along a waterway."

"H'm!" coughed Harris. "My directors won't want to pay you two dollars a day for nothing."

"Two dollars a day?" said Joe in his gentle voice. "I should n't 'a' thought the two hundred times a hundred thousand dollars could stand a strain like that!"

I laughed. "Look here, November, I think I'd like to make this bargain for you."

"Yes, sure," said the young woodsman.

"Then I'll sell your services to Mr. Harris here for five dollars a day if you fail, and ten per cent of the sum you recover if you succeed."

Joe looked at me with wide eyes, but he said nothing.

"Well, Harris, is it on or off?" I asked.

"Oh, on, I suppose, confound you!" said Harris.

November looked at both of us with a broad smile.

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

Twenty hours later, Joe, a police trooper named Hobson, and I were deep in the woods. We had hardly paused to interview the farmer at Roberville, and then had passed on down the old deserted roads until at last we entered the forest, or, as it is locally called, the "bush."

"Where are you heading for?" Hobson had asked Joe.

"Red River, because if it really was Atterson the farmer saw, I guess he'll have gone up there."

"Why do you think that?"

"Red River's the overflow of Snow Lake, and there is several trappers has canoes on Snow Lake. There's none of them trappers there now in July month, so he can steal a canoe easy. Besides, a man who fears pursuit always likes to get into a country he knows, and you heard Mr. Harris say how Atterson had fished Red River two vacations. Besides"—here Joe stopped and pointed to the ground—"them's Atterson's tracks," he said. "Leastways, it's a black fox to a lynx pelt they are his."

"But you've never seen him. What reason have you . . . ?" demanded Hobson.

"When first we happened on them about four hours back, while you was lightin' your pipe," replied Joe, "they come out of the bush, and when we reached near Cartier's place they went back into the bush again. Then a mile beyond Cartier's out of the bush they come on to the road again. What can that circumventin' mean? Feller who made the tracks don't want to be seen. Number 8 boots, city-made, nails in 'em, rubber heels. Come on."

I will not attempt to describe our journey hour by hour, nor tell how November held to the trail, following it over areas of hard ground and rock, noticing a scratch here and a broken twig there. The trooper, Hobson, proved to be a good track-reader, but he thought himself a better, and, it seemed to me, was a little jealous of Joe's obvious superiority.

We slept that night beside the trail. According to November, the thief was now not many hours ahead of us. Everything depended upon whether he could reach Red River and a canoe before we caught up with him. Still it was not possible to follow a trail in the darkness, so perforce we camped. The next morning November wakened us at daylight and once more we hastened forward.

For some time we followed Atterson's footsteps and then found that they left the road. The police officer went crashing along till Joe stopped him with a gesture.

"Listen!" he whispered.

We moved on quietly and saw that, not fifty yards ahead of us, a man was walking excitedly up and down. His face was quite clear in the slanting sunlight, a resolute face with a small, dark mustache, and a two-days' growth of beard. His head was sunk upon his chest in an attitude of the utmost despair, he waved his hands, and on the still air there came to us the sound of his monotonous muttering.

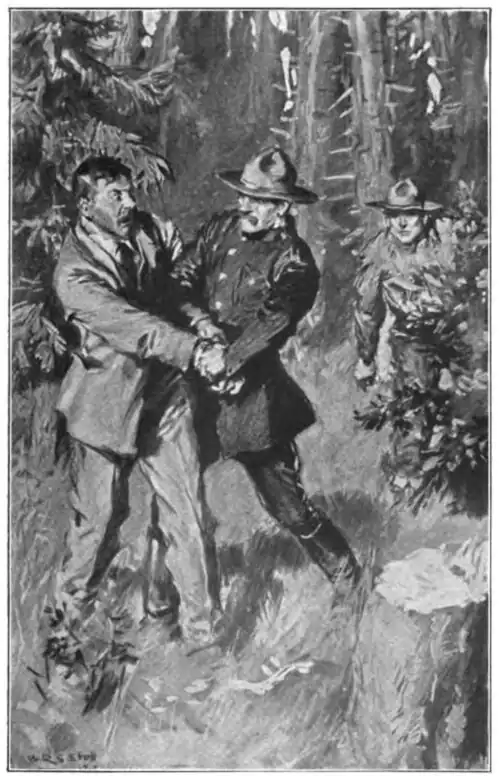

We crept upon him. As we did so, Hobson leapt forward and, snapping his handcuffs on the man's wrists, cried:—

"Cecil Atterson, I've got you!"

Atterson sprang like a man on a wire, his face went dead white. He stood quite still for a moment as if dazed, then he said in a strangled voice:—

"Got me, have you? Much good may it do you!"

"Hand over that packet you're carrying," answered Hobson.

There was another pause.

"By the way, I'd like to hear exactly what I'm charged with, " said Atterson.

"Like to hear!" said Hobson. "You know! Theft of one hundred thousand dollars from the Grand Banks. May as well hand them over and put me to no more trouble!"

"You can take all the trouble you like," said the prisoner.

Hobson plunged his hand into Atterson's pockets, and searched him thoroughly, but found nothing.

"They are not on him," he cried. "Try his pack."

From the pack November produced a square bottle of whiskey, some bread, salt, a slab of mutton—that was all.

"Where have you hidden the stuff?" demanded Hobson.

Suddenly Atterson laughed.

"So you think I robbed the bank?" he said. "I've my own down on them, and I'm glad they've been hit by some one, though I'm not the man. Anyway, I'll have you and them for wrongful arrest with violence."

Cecil Atterson, I've got you! Then he turned to us. "You two are witnesses."

"Do you deny you're Cecil Atterson?" said Hobson.

"No, I'm Atterson right enough."

"Then look here, Atterson, your best chance is to show us where you've hid the stuff. Your counsel can put that in your favour at your trial."

"I'm not taking any advice just now, thank you. I have said I know nothing of the robbery."

Hobson looked him up and down. "You'll sing another song by and by," he said ironically. "We may as well start in now, Joe, and find where he's cached that packet."

November was fingering over the pack which lay open on the ground, examining it and its contents with concentrated attention. Atterson had sunk down under a tree like a man wearied out.

Hobson and Joe made a rapid examination of the vicinity. A few yards brought them to the end of Atterson's tracks.

"Here's where he slept," said Hobson. "It's all pretty clear. He was dog-tired and just collapsed. I guess that was last night. It's an old camping-place, this." The policeman pointed to weathered beds of balsam and the scars of several camp-fires.

"Yes," he continued, "that's what it is. But the trouble is where has he cached the bank's property?"

For upwards of an hour Hobson searched every conceivable spot, but not so November Joe, who, after a couple of quick casts down to the river, made a fire, put on the kettle, and lit his pipe. Atterson, from under his tree, watched the proceedings with a drowsy lack of interest that struck me as being particularly well simulated.

At length Hobson ceased his exertions, and accepted a cup of the tea Joe had brewed.

"There's nothing cached round here," he said in a voice low enough to escape the prisoner's ear, "and his"—he indicated Atterson's recumbent form with his hand—"trail stops right where he slept. He never moved a foot beyond that nor went down to the river, one hundred yards away. I guess what he's done is clear enough."

"Huh!" said Joe. "Think so?"

"Yep! The chap's either cached them or handed them to an accomplice on the back trail."

"That's so? And what are you going to do next?"

"I'm thinking he'll confess all right when I get him alone."

He stood up as November moved to take a cup of tea over to Atterson.

"No, you don't," he cried. "Prisoner Atterson neither eats nor drinks between here and Quebec unless he confesses where he has the stuff hid."

"We'd best be going now," he continued as November, shrugging, came back to the fireside. "You two walk on and let me get a word quiet with the prisoner."

"I'm staying here," said Joe.

"What for?" cried Hobson.

"I'm employed by Bank Manager Harris to recover stolen property," replied Joe.

"But," expostulated Hobson, "Atterson's trail stops right here where he slept. There are no other tracks, so no one could have visited him. Do you think he's got the bills and papers hid about here after all?"

"No," said Joe.

Hobson stared at the answer, then turned to go.

"Well," said he, "you take your way and I'll take mine. I reckon I'll get a confession out of him before we reach Quebec. He's a pretty tired man, and he don't rest nor sleep, no, nor sit down, till he's put me wise as to where he hid the stuff he stole."

"He won't ever put you wise," said Joe definitely.

"Why do you say that?"

"'Cause he can't. He don't know himself."

"Bah!" was all Hobson's answer as he turned on his heel.

November Joe did not move as Hobson, his wrist strapped to Atterson's, disappeared down the trail by which we had come.

"Well, " I said, "what next?"

"I'll take another look around." Joe leapt to his feet and went quickly over the ground. I accompanied him.

"What do you make of it?" he said at last.

"Nothing," I answered. "There are no tracks nor other signs at all, except these two or three places where old logs have been lying—I expect Atterson picked them up for his fire. I don't understand what you are getting at any more than Hobson does."

"Huh!" said Joe, and led the way down to the river, which, though not more than fifty yards away, was hidden from us by the thick trees.

It was a slow-flowing river, and in the soft mud of the margin I saw, to my surprise, the quite recent traces of a canoe having been beached. Beside the canoe, there was also on the mud the faint mark of a paddle having lain at full length.

Joe pointed to it. The paddle had evidently, I thought, fallen from the canoe, for the impression it had left on the soft surface was very slight.

"How long ago was the canoe here?"

"At first light—maybe between three and four o'clock," replied Joe.

"Then I don't see how it helps you at all. Its coming can't have anything to do with the Atterson robbery, for the distance from here to the camp is too far to throw a packet, and the absence of tracks makes it clear that Atterson cannot have handed the loot over to a confederate in the canoe. Is n't that right?"

"Looks that way," admitted Joe.

"Then the canoe can be only a coincidence."

November shook his head. "I would n't go quite so far as to say that, Mr. Quaritch."

Once again he rapidly went over the ground near the river, then returned to the spot where Atterson had slept, following a slightly different track to that by which we had come. Then taking the hatchet from his belt, he split a dead log or two for a fire and hung up the kettle once more. I guessed from this that he had seen at least some daylight in a matter that was still obscure and inexplicable to me.

"I wonder if Atterson has confessed to Hobson yet," I said, meaning to draw Joe.

"He may confess about the robbery, but he can't tell any one where the bank property is."

"You said that before, Joe. You seem very sure of it."

"I am sure. Atterson does n't know, because he's been robbed in his turn."

"Robbed!" I exclaimed.

Joe nodded.

"And the robber?"

"'Bout five foot six; light-weight; very handsome; has black hair; is, I think, under twenty-five years old; and lives in Lendeville, or near it."

"Joe, you've nothing to go on!" I cried. "Are you sure of this? How can you know?"

"I'll tell you when I've got those bank bills back. One thing's sure—Atterson'll be better off doing five years' hard than if he'd— But here, Mr. Quaritch, I'm going too fast. Drink your tea, and then let us make Lendeville. It's all of eight miles upstream."

It was still early afternoon when we arrived in Lendeville, which could hardly be called a village, except in the Canadian acceptance of that term. It was composed of a few scattered farms and a single general store. Outside one of the farmhouses Joe paused.

"I know the chap that lives in here," he said. "He's a pretty mean kind of a man, Mr. Quaritch. I may find a way to make him talk, though if he thought I wanted information he'd not part with it."

We found the farmer at home, a dour fellow, whose father had emigrated from the north of Scotland half a century earlier.

"Say, McAndrew," began Joe, "there's a chance I'll be bringing a party up on to Red River month after next for the moose-calling. What's your price for hiring two strong horses and a good buckboard to take us and our outfit on from here to the Burnt Lands by Sandy Pond?"

"Twenty dollars."

"Huh!" said Joe, "we don't want to buy the old horses!"

The Scotchman's shaven lips (he wore a chin-beard and whiskers) opened. "It would na' pay to do it for less."

"Then there's others as will."

"And what might their names be?" inquired McAndrew ironically.

"Them as took up Bank-Clerk Atterson when he was here six weeks back."

"Weel, you're wrang!" cried McAndrew, "for Bank-Clerk Atterson juist walked in with young Simon Pointarré and lived with the family at their new mill. So the price is twenty, or I'll nae harness a horse for ye!"

"Then I'll have to go on to Simon Pointarré. I've heard him well spoken of."

"Have ye now? That's queer, for he . . ."

"Maybe, then, it was his brother," said Joe quickly.

"Which?"

"The other one that was with Atterson at Red River."

"There was nae one, only the old man, Simon, and the two girrls."

"Well, anyway, I've got my sportsmen's interests to mind," said November, "and I'll ask the Pointarré's price before I close with yours."

"I'll make a reduce to seventeen dollars if ye agree here and now."

November said something further of Atterson's high regard for Simon Pointarré, which goaded old McAndrew to fury.

"And I'll suppose it was love of Simon that made him employ that family," he snarled. "Oh, yes, that's comic. 'T was Simon and no that grinning lassie they call Phèdre! . . . Atterson? Tush! I tell ye, if ever a man made a fule o' himself . . ."

But here, despite McAndrew's protests, Joe left the farm.

At the store which was next visited, we learned the position of the Pointarré steading and the fact that old Pointarré, the daughters, Phèdre and Claire, and one son, Simon, were at home, while the other sons were on duty at the mill.

Joe and I walked together along various trails until from a hillside we were able to look down upon the farm, and in a few minutes we were knocking at the door.

It was opened by a girl of about twenty years of age; her bright brown eyes and hair made her very good-looking. Joe gave her a quick glance.

"I came to see your sister," said he.

"Simon," called the girl, "here's a man to see Phèdre."

"What's his business?" growled a man's voice from the inner room.

"I've a message for Miss Pointarré," said Joe.

"Let him leave it with you, Claire," again growled the voice.

"I was to give it to her and no one else," persisted Joe.

This brought Simon to the door. He was a powerful young French-Canadian with upbrushed hair and a dark mustache. He stared at us.

"I've never seen you before," he said at last.

"No, I'm going south and I promised I'd leave a message passing through," replied Joe.

"Who sent you?"

"Can't tell that, but I guess Miss Pointarré will know when I give her the message."

"Well, I suppose you'd best see her. She's down bringing in the cows. You'll find her below there in the meadow"; he waved his arm to where we could see a small stream that ran under wooded hills at a distance of about half a mile. "Yes, you'll find her there below."

Joe thanked him and we set off.

It did not take us long to locate the cows, but there was no sign of the girl. Then, taking up a well-marked trail which led away into the bush, we advanced upon it in silence till, round a clump of pines, it debouched upon a large open shed or byre. Two or three cows stood at the farther end of it, and near them with her back to us was a girl with the sun shining on the burnished coils of her black hair.

A twig broke under my foot and she swung round at the noise.

"What do you want?" she asked.

She was tall and really gloriously handsome.

"I've come from Atterson. I've just seen him," said November.

I fancied her breath caught for the fraction of a second, but only a haughty surprise showed in her face.

"There are many people who see him every day. What of that?" she retorted.

"Not many have seen him to-day, or even yesterday."

Her dark blue eyes were fixed on November. "Is he ill? What do you mean?"

"Huh! Don't they read the newspaper in Lendeville? There's something about him going round. I came thinking you'd sure want to hear," said November.

The colour rose in Phèdre's beautiful face.

"They're saying," went on Joe, "that he robbed the bank where he is employed of a hundred thousand dollars, and instead of trying to get away on the train or by one of the steamers, he made for the woods. That was all right if a Roberville farmer had n't seen him. So they put the police on his track and I went with the police."

Phèdre turned away as if bored. "What interest have I in this? It ennuies me to listen."

"Wait!" replied November. "With the police I went, and soon struck Atterson's trail on the old Colonial Post Road, and in time come up with Atterson himself nigh Red River. The police takes Atterson prisoner and searches him."

"And got the money back!" she said scornfully. "Well, it sounds silly enough. I don't want to hear more."

"The best is coming, Miss Pointarré. They took him but they found nothing. Though they searched him and all roundabout the camp, they found nothing."

"He had hidden it, I suppose."

"So the police thought. And I thought the same, till . . ." (November's gaze never left her face) "till I see his eyes. The pupils were like pin-points in his head." He paused and added, "I got the bottle of whiskey that was in his pack. It'll go in as evidence."

"Of what?" she cried impatiently.

"That Atterson was drugged and the bank property stole from him. You see," continued Joe, "this robbery was n't altogether Atterson's own idea."

"Ah!"

"No, I guess he had the first notion of it when he was on his vacation six weeks back. . . . He was in love with a wonderful handsome girl. Blue eyes she had and black hair, and her teeth was as good as yours. She pretended to be in love with him, but all along she was in love with—well, I can't say who she was in love with—herself likely. Anyway, I expect she used all her influence to make Atterson rob the bank and then light out for the woods with the stuff. He does all she wants. On his way to the woods she meets him with a pack of food and necessaries. In that pack was a bottle of drugged whiskey. She asks him where he's going to camp that night, he suspects nothing and tells her, and off she goes in a canoe up Red River till she comes to opposite where he's lying drugged. She lands and robs him, but she don't want him to know who done that, so she plays an old game to conceal her tracks. She's a rare active young woman, so she carries out her plan, gets back to her canoe and home to Lendeville. . . . Need I tell any more about her?"

During Joe's story Phèdre's colour had slowly died away.

"You are very clever!" she said bitterly. "But why should you tell me all this?"

"Because I'm going to advise you to hand over the hundred thousand dollars you took from Atterson. I'm in this case for the bank."

"I?" she exclaimed violently. "Do you dare to say that I had anything whatever to do with this robbery, that I have the hundred thousand dollars? . . . Bah! I know nothing about it. How should I?"

Joe shrugged his shoulders. "Then I beg your pardon, Miss Pointarré, and I say goodbye. I must go and make my report to the police and let them act their own way." He turned, but before he had gone more than a step or two, she called to him.

"There is one point you have missed for all your cleverness," she said. "Suppose what you have said is true, may it not be that the girl who robbed Atterson took the money just to return it to the bank?"

"Don't seem to be that way, for she has just denied all knowledge of the property, and denied she had it before two witnesses. Besides, when Atterson comes to know that he's been made a cat's-paw of, he'll be liable to turn King's evidence. No, miss, your only chance is to hand over the stuff—here and now."

"To you!" she scoffed. "And who are you? What right have you . . ."

"I'm in this case for the bank. Old McAndrew knows me well and can tell you my name."

"What is it?"

"People mostly call me November Joe."

She threw back her head—every attitude, every movement of hers was wonderful.

"Now, supposing that the money could be found . . . what would you do?"

"I'd go to the bank and tell them I'd make shift to get every cent back safe for them if they'd agree not to prosecute . . . anybody."

"So you are man enough not to wish to see me in trouble?"

November looked at her.

"I was sure not thinking of you at all," he said simply, "but of Bank-Clerk Atterson, who's lost the girl he robbed for and ruined himself for. I'd hate to see that chap over-punished with a dose of gaol too. . . . But the bank people only wants their money, and I guess if they get that they'll be apt to think the less said about the robbery the better. So if you take my advice—why, now's the time to see old McAndrew. You see, Miss Pointarré, I've got the cinch on you."

She stood still for a while. "I'll see old man McAndrew," she cried suddenly. "I'll lead. It's near enough this way."

Joe turned after her, and I followed. Without arousing McAndrew's suspicions, Joe satisfied the girl as to his identity.

Before dark she met us again. "There!" she said, thrusting a packet into Joe's hand." But look out for yourself! Atterson is n't the only man who'd break the law for love of me. Think of that at night in the lonely bush!"

I saw her sharp white teeth grind together as the words came from between them.

"My!" ejaculated November looking after her receding figure, "she's a bad loser, ain't she, Mr. Quaritch?"

We went back into Quebec, and Joe made over to the bank the amount of their loss as soon as Harris, the manager, agreed (rather against his will) that no questions should be asked nor action taken.

The same evening I, not being under the same embargo regarding questions, inquired from Joe how in the world the fair Phèdre covered her tracks from the canoe to where Atterson was lying.

"That was simple for an active girl. She walked ashore along the paddle, and after her return to the canoe threw water upon the mark it made in the mud. Did n't you notice how faint it was?"

"But when she got on shore—how did she hide her trail then?"

"It's not a new trick. She took a couple of short logs with her in the canoe. First she'd put one down and step onto it, then she'd put the other one farther and step onto that. Next she'd lift the one behind, and so on. Why did she do that? Well, I reckon she thought the trick good enough to blind Atterson. If he'd found a woman's tracks after being robbed, he'd have suspected."

"But you said before we left Atterson's camp that whoever robbed him was middle height, a light weight, and had black hair."

"Well, had n't she? Light weight because the logs was n't much drove into the ground, not tall since the marks of them was so close together."

"But the black hair?"

Joe laughed. "That was the surest thing of the lot, and put me wise to it and Phèdre at the start. Twisted up in the buckle of the pack she gave Atterson I found several strands of splendid black hair. She must 'a' caught her hair in the buckles while carrying it."

"But, Joe, you also said at Red River that the person who robbed Atterson was not more than twenty-five years old?"

"Well, the hair proved it was a woman, and what but being in love with her face would make a slap-up bank-clerk like Atterson have any truck with a settler's girl? And them kind are early ripe and go off their looks at twenty-five. I guess, Mr. Quaritch, her age was a pretty safe shot."