November Joe/Chapter 7

Chapter VII

The Case of Miss Virginia Planx

November Joe and I had been following a moose since daybreak, moving without speech. We had not caught even a glimpse of the animal; all that I had seen were the huge, ungainly tracks sunk deep in swampy ground or dug into the hillsides.

Suddenly from somewhere ahead there broke out the sound of two shots, and, after a minute, of two more.

"That's mean luck," said November. "It'll scare our moose, sure. Pity! He's got a fine set o' horns, more'n fifty-six inches in the spread."

"How can you tell that? You haven't seen him?"

Joe's grey eyes took on the look I now knew well.

"I'm certain sure they spread not less than fifty-six and not more'n sixty. . . . My! Look out! Them shots has put him back. He's coming to us!"

There was a crashing in the undergrowth sounding ever nearer, and soon a magnificent bull-moose came charging into sight.

"He's your moose!" said Joe, as my shot rang out. "You hit him fair behind the shoulder. No need to shoot again."

The great brute, weighing over twelve hundred pounds, was stumbling forward in his death-rush; all at once he collapsed, and silence reigned once again in the forest. We ran up. He was quite dead. I turned to Joe.

"Now we'll be able to measure his horns," I said, a little maliciously; for, to tell the truth, I thought Joe had been drawing me when he pretended to be able to tell within four inches the measurements of the antlers of a moose which he had not seen.

"Let's have that fine steel measuring-tape you carry," said Joe.

I produced it, and he stretched it across the horns.

"Fifty-eight inches," said he.

I looked at my hunter.

"It ain't nothing but simple," he said. "I see the scrape of his horns over and over ag'in where he passed between the spruces. You can always tell the size of horns that way."

I laughed. "Confound you, Joe! You always—"

But here I was checked. Bang, bang! went the rifle in the distance, and again, Bang, bang! After an interval the shots were repeated.

"Two shots going on at steady intervals," said Joe. "That's a call for help. There they go again. We'd best follow them up."

We travelled for half an hour, guided by the sounds; then Joe stopped.

"Here's his trail—a heavy man not used to the woods."

"I can see he's heavy by the deep prints," said I. "But why do you say he's not used to woods? He's wearing moccasins, is n't he?"

"Sure he is." November Joe pointed to the tracks. "But he's walking on his heels and on the sides of his feet. A man don't do that unless his feet is bruised and sore."

We hurried on, and soon came in sight of a man standing among the trees. We saw him raise his rifle and fire twice straight upwards to the sky.

"It's Planx!" said Joe in surprise.

"What? The millionaire you went into the woods with to locate timber last year?"

"The identical man."

As we approached, Joe hailed him. Planx started, and then began to move as quickly as he could towards us. He was a thick-shouldered, stout man, his big body set back upon his hips, his big chin thrust forward in a way that accentuated the arrogance of his bulging lips and eyes.

"Can you guide me to the house of November―Ho! It's you, Joe!"

"Yes, Mr. Planx."

"That is lucky, for I need your help. I need it as no man has ever needed it before."

"Huh! How's that?"

"My daughter was murdered yesterday."

The words made me gasp, and not me only.

"Miss Virginny!" cried Joe. "You can't mean that. Nobody would be brute enough to kill Miss Virginny!"

Planx made no reply, but stared at Joe in a sombre and convincing silence.

"When did it happen?"

"Some time before five o'clock yesterday evening. But I'll put you wise as we walk. I'm stopping at Wilshere's camp, four miles along. Ed told me you lived round here, and I set out to find you."

As we walked Planx gave us the following facts: It appeared that he had been spending the last two weeks in a log hut which had been lent him by a friend, Mr. Wilshere. His household consisted of one servant,—his daughter's nurse, a middle-aged woman whom they had brought with them from New York,—two guides, and a man cook. On the previous day Miss Virginia had taken her rod after lunch, as she had often done before, and gone off to the river to fish.

"What hour was it when she left?" asked November.

"Half-past one. About three o'clock one of the guides who was cutting wood near the river saw her. She had put down her rod and was reading a book. At five I went to join her. She was not there. Her rod lay broken and there were signs of a struggle and the tracks of two men. I shouted for Ed, the old guide. He came running down and we took up the trail. It led us straight over to Mooseshank Lake. The ruffians had put her in our own canoe and gone out on the lake."

Planx paused, and presently continued:—

"We went round the lake and found on the far side the spot where they had beached the canoe. Leading up into the woods from that point, we again struck the trail of the two men, but my daughter was no longer with them."

"Are you sure of that?"

"As certain as you'll be yourself later on. From the river to the lake the tracks showed they were carrying her. When they left the canoe they were going light. They must have drowned her in the lake. It's clear enough. Presently I saw something floating on the water, it was her hat."

"Had Miss Virginny any jewelry on her?" asked Joe.

"A watch and a necklace."

"What value?"

"Seven or eight hundred dollars."

"Huh, " said November reflectively. "And what did you do after finding her hat?"

"We trailed the two villains until they got on to some rocky ground. It was too dark then to do more, so we returned. Ed (he's the best tracker of my two guides) got away at dawn to see if he could n't puzzle out the trail."

"Did he?"

"He had not returned when I started for your place. "

"We've only three hours daylight left," said Joe. "Let's travel."

Which we did, the huge Planx, for all his unwieldy build, keeping up wonderfully well.

In about an hour we reached the river. A man was standing on the bank.

"Any luck, Ed?" shouted Planx.

"Could n't find another sign among them rocks."

Planx turned to Joe. "Five thousand dollars if you lay hands on them," he said. "You, Ed, go back to the house and see if there's any news."

Joe was already at work. By the river the traces were so plain that any one could read them—the slender feet of the victim and the larger footprints of the two men. The fishing-rod, snapped off towards the top of the middle joint, had been left where it had fallen. It seemed as if the girl had tried to defend herself with it.

When he examined this spot, Joe made one or two casts up and down the bank, hovering here and there while Planx stood on the top of the slope and gloomily watched him. Now and then he asked a question.

"She started fishing about an acre downstream, got her line hung up twice, and the second time lost her fly. She had a fish on after that, but never landed it," said Joe in reply.

"Bah! How do you know all this?" growled Planx.

"First time her tracks show where she disengaged her hook from a tree; next time I see the hook sticking in a branch. As to the fish, it's plain enough. First she runs upstream, then down, then up again, then back in a bit of a circle—must have been a heavy fish that made her move about like that. Now let's get to the lake."

November literally nosed his way along. The moccasined tracks of the two men showed faintly here and there on the softer parts of the ground.

"Looks as if they was toting something," said Joe. "They must 'a' carried her. Stop! They set her down here for a spell."

Another moment brought us over the rise and in sight of Mooseshank Lake. I halted involuntarily.

The lake lay black and still upon the knees of a great mountain. Forests climbed to the margin and looked down into its depths on the one side; on the other the water lapsed in slow pulsations on a beach of stones, that stretched beneath bare and towering cliffs. Sunshine yet blazed upon the treetops, but the lake was already sunk in shadow. The place seemed created for the scene of a tragedy.

November had pushed on to the spot where footprints and other signs showed where the men had entered the canoe. The deep slide of a moccasined foot in the mud seemed to tell of the effort it required to get the girl embarked.

"They took her out on the lake and murdered her!" groaned Planx. "Dragging? There's no use dragging, that water goes plumb down to the root of the world. It was surveyed last year by Wilshere's people, and they could get no soundings."

After that we went round to the other side of the lake, and saw the beached canoe. The two sets of moccasined tracks showed clearly on the strip of mud by the water, but were soon lost in the tumbled débris of a two-year-old stony landslip over which trailing appeared quite impossible. November was busy about this landing-place for a longer time than I expected, then he crossed the landslide at right angles and disappeared from our view.

"There's a stream over there comes in a little waterfall from the cliffs," said Planx, pointing after Joe. "You can hear it."

That was all the conversation that passed between us until Joe returned. He came hurrying towards us.

"Say, Mr. Planx," he began.

"What is it?"

"She is n't dead."

"What?"

"Anyways, she was n't when she passed here."

"Then where are her tracks?" demanded Planx, pointing to the footprints on the mud. "Those were made by two full-sized men."

"Aye," said Joe, "maybe I can tell you more about that later. But I have a proof here that you will think mighty good." He drew out a little leather case I had given him, and extracted from it a long hair of a beautiful red-gold colour. "Look at that! I found it in the spruces above there."

Planx took it gently in his great fingers. He was visibly much moved. For a few seconds he held it without speaking, then, "That grew on Virginia's head sure enough, Joe. Is it possible my girl is alive?"

"She is, sure! Don't be afeared, you'll soon have news of her. I can promise you that, Mr. Planx. This was n't no case of murder. It's just an abduction. They'd never be such fools as to kill her! They're cuter than that. Isn't she your daughter? They'll hold her to big ransom. That's their game."

An ugly look came into Planx's eyes. "That's their game, is it? I'm not a man that it is easy to milk dollars from," said he.

By this time it was growing too dark for Joe to work any longer. We crossed the lake with Planx, and that night Joe and I camped near the end of Mooseshank Lake, where a stream flowed from it.

"We're not far from the little waterfall and the string of water that drops from it down the hill near the landslip," said Joe. "I want to get back there early in the morning, and this is the nearest way."

But after events altered his intentions.

At dawn, while we were having breakfast, Joe stood up and stared into the trees that grew thick behind us. As he called out, I looked back and saw the indistinct figure of a man in their shadow watching us. He beckoned, and we approached him. I saw he was young, with a pale face and rather shabby town-made clothes.

"Don't you remember Walter Calvey, November?" he said, holding out his hand. "I was with you and Mr. Planx, and—and—her last year in the woods."

"Huh, yes, and what are you doing here, Mr. Calvey?" asked Joe, shaking hands.

"I heard about Virginia—how could I keep away after that?" exclaimed Calvey.

"You've no cause to fret yet," said Joe.

"What? When they've killed her! I'll go with you, and if we can find those—"

"Huh! She's not dead! Take my word for it!" Joe's grey eyes gave me a roguish look. "Why, I've got a thing here in my pocketbook you'd give me a hundred dollars for!" He held the red-gold hair up to the light of the rising sun.

Calvey shook from head to foot.

"Virginia's! You could n't find its match in Canada! Tell me—"

"I can't wait to tell you and you can't wait to hear. Light out now. Old man Planx could make it unhealthy for you."

"You're right! He hates me because Virginia won't marry Schelperg, of the Combine. He has n't let us meet for months. And more than that, he's ruined me and my partner in business. It was easy for a rich man to do that," added Calvey bitterly.

"You go and start into business again," advised Joe. "I'll send you word first thing I know for certain."

But it was some time before he could induce Calvey to leave us. After he had gone, I wondered whether Joe suspected him of having a hand in spiriting away Virginia. Presently I asked him.

Joe shook his head. "He could n't have done it if he wanted to! He's a good young chap, but look at his boots and his clothes—he was bred on a pavement, but he's Miss Virginny's choice for all that. We'll start now, Mr. Quaritch, just where I found that bit of gold caught in a branch that hangs over the little stream up above there. You see, she lost her hat, and she has a splendid lot of hair, and so when I could find no tracks,—for they came down the bed of the stream,—I searched 'bout as high as her head. I guessed she'd be liable to catch her hair in a branch."

But we had hardly started when we heard the voice of Planx roaring in the wood below us. He was coming along at an extraordinary pace in spite of his ungainly, rolling stride.

"You were right, Joe, Virginia is alive! It is a case of abduction. See what I have here."

He held a long stick or wand in his hand. The top of the wand was roughly split, and a scrap of paper stuck in the cleft.

"Ed's just found this in the canoe on the lake," he went on. "These blackguards must have come back in the night and put it there."

"What have they said in the paper?" asked November.

"'You must pay to get your daughter back. If you want our terms, come to the old log camp on Black Lake to-morrow night. No tricks. We have you rounded up, sure. Don't try to track us, or we will make it bad for her.'"

Joe took the stick and examined it with care.

"They meant to leave it stuck in the ground Indian fashion," said I, for I had seen letters of Indians made conspicuous in this way by lonely banks of rivers and other places where wandering hunters pass.

"They meant to do that, but found the canoe handy." Joe touched the ends of the wand, "Green spruce wood, cut near their camp," said he.

"There's plenty of spruce like that right here," objected Planx; "why do you say it was cut near their camp?"

"It's cut and split with a heavy axe, such as no man ever carries about with him. Well, we'd best do no more tracking till we see the chaps that has Miss Virginny. It's Black Lake to-night, then?"

"Yes, meet me by the alder swamp that's west of Wilshere's place," said Planx.

He stayed talking for a while, and after he was gone we shifted our camp to a more convenient spot and waited for the evening.

Black Lake lies at a distance of some five miles from Wilshere's, and as it abounded in grey trout, a log hut had been built for the convenience of the occasional fishermen who visited it. Starting early we came in sight of the lake while the glow was still in the western sky.

On the way, Planx made known to us his plan of campaign. It was a simple one. He would get the men into the hut, and speak them fair till a favourable moment presented itself, when he would demand the surrender of his daughter under threat of shooting the kidnappers if they refused or demurred.

"There are three of us, and we can fix them easy," said Planx.

November Joe shook his head. "They're not near such big fools as you think them," he remarked.

We had stopped on some high ground in the shelter of the woods, from which we could see the fishing-hut. Planx took a look round with his field glass.

"No sign of life anywhere," he said.

In fact, when we approached it after darkness had fallen, the place seemed entirely deserted. Nevertheless, Joe signed to us to wait while he went on to reconnoitre. He vanished with his silent, Indian-like glide, his movements as inaudible as those of a ghost. In about five minutes a light suddenly sprang up in the hut and Joe's voice called us.

As we entered the door, I saw Joe had kindled a lantern and was pointing to a piece of paper which lay on the rough-hewn table.

Planx seized upon it.

"The same writing as before. Listen to this: 'If you will swear to give us safe conduct, we will come to talk it out. If you agree to this, wave the lantern three times on the lake shore, and that wil mean you give your oath to let us come and go freely.'"

"I told you they were not fools," said Joe. "What's the orders now, Mr. Planx?"

Planx handed Joe the lantern. "Go and wave the lantern."

From the door of the hut we watched November as he walked down to the lake. At the third swing of the light, a voice hailed him.

"You hear? They were waiting in a canoe," said Planx to me. "That's 'cute."

Then followed the splash of paddles and the rasp of the frosted rushes as the canoe took the shore. Joe had returned by this time, and hung up the lantern so that it lit the whole of the hut. Then the three of us stood together at one side of the table.

Our visitors hesitated outside the door.

"There are only two of them," whispered Planx.

As he spoke, a short, bearded man, in a thick overcoat, stepped into the light, followed by a tall and strongly built companion. Both wore black visor masks, with fringe covering the mouth. I noticed they were shod in moccasins.

"Evenin'," said the tall man, who was throughout the spokesman.

To this no one made any reply, so, after a second or so, he went on.

"My partner and me is come to make you an offer, Mr. Planx. We've got your daughter where you'll never find her, where you'd never dream of looking for her."

"Don't be too sure of that," growled Planx.

The tall man passed over the remark without notice.

"If we agree on a bargain, she shall be returned to you unhurt three days from the time the price is paid over. And that price is one hundred thousand dollars.

"Those are our terms. The question for you is, do you want your daughter, or do you not?"

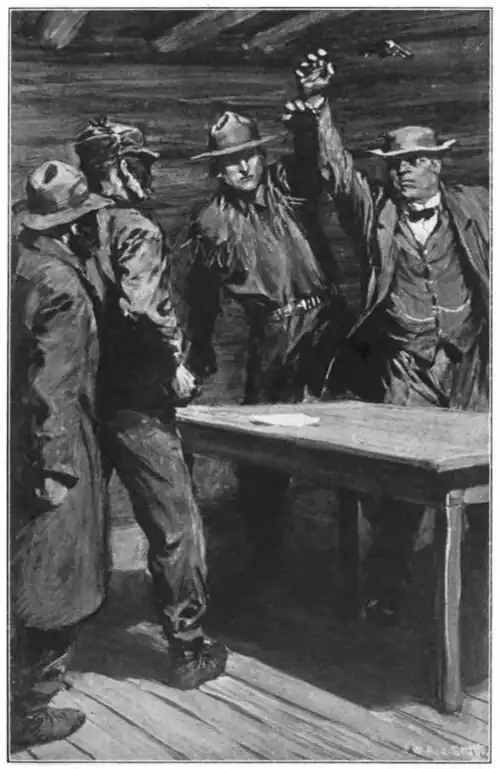

The next incident was as swift as it was unexpected.

"I conjecture that is something of an easy question to answer," said Planx in his slow tones. "In fact I—"

On the word he slipped out a revolver. But quick as was Planx's hand to carry out the impulse of his brain, Joe's was quicker. He knocked the revolver from Planx's grasp.

"You treacherous dog, Planx!" cried the kidnapper. "Is that how you keep faith? Well, we have a reply to that, too. We offered to give up the girl for one hundred thousand dollars, now we make the price one hundred and fifty thousand!"

"I'll never pay a cent of it!" shouted Planx.

"When you come to change your mind," replied the kidnapper quietly, "just hang a white handkerchief on one of the trees at the edge of this wood. Then put the money in notes in that tin on the shelf. Leave us two clear days, and you'll get your girl back safe. But if you monkey, it will be the worse for her."

Without more words, the two masked men left the hut, and before long we heard the sound of their paddles upon the water. For a few moments we listened until the noise died away, then, like the explosion of a thunderstorm, Planx opened upon Joe.

November faced the storm with an entirely

Joe knocked the revolver from Planx's grasp placid aspect until I began to wonder at his patience. But when at last he spoke, the other fell dumb as if Joe had struck him.

"That's settled, Mr. Planx. You've done with me, and I've done with you. Now quiet down and out!"

Planx opened his lips as if to speak, but, seeing Joe's face, he changed his mind and rushed from us into the darkness.

At once Joe put out the light. "We can't trust Planx just at the moment. He's fair mad. But we'll have him back in half an hour to show him the way back to Wilshere's," he remarked with a chuckle.

And in fact this was exactly what happened. It was a subdued but still a very resentful Planx whom we escorted through the dark woods. On our way back to our camp Joe made a détour to examine the tracks of the kidnappers by the light of the lantern which he had carried with him.

As had been the case by Mooseshank Lake, so now we found the trails very clear near the waterside. Joe studied them for a long time.

"What do you make of them?" asked he, at last.

"Moccasins—there are the footprints of one of the same men as we saw before, I think," I answered.

Joe nodded.

"Well, you're out of it now at any rate," said I.

"And what about my promise to Calvey?" he rejoined. "I'm deeper in it than ever. I've got to find Miss Virginny sure."

"You can't track her because of that threat in the letter to Planx?"

"That's so, and I have another reason ag'in' it."

"What is it?"

"That I'll be speaking to Miss Virginny herself before to-morrow night," said Joe quietly, nor, having made this dramatic announcement, would he say more.

The next morning Joe was early astir.

"What are you going to do to-day?" said I.

"I'm going to find out the name of the man that has Miss Virginny hid away. If you'll wait here, Mr. Quaritch, I'll come back as soon as I've done it. You've got your rod and there's plenty of fish in the lake."

With that I had to be content. Through the pleasant morning hours I fished, but my mind was not on the sport. Instead, I was puzzling over the facts of the disappearance of Miss Virginia Planx. Before starting, Joe had laid a bet with me that he would come back with the name of her abductor, and I was wondering what clue he had to go upon. Hardly any that I could think of—the trail of the two men and the golden hair, very little more. Yet November had committed himself in the matter, and he was not a man to talk until he could make good his words. I must own the hours passed very slowly while the sun reached and then began to decline from the zenith.

About two o'clock, I heard November hail me.

"What about the bet?" I called on sight of him. "Who pays?"

"You pay, Mr. Quaritch," said Joe.

"Why, who is it, then?"

"A fellow called Hank Harper."

"Why, I've heard of him. He passes for a man of high character."

Joe laughed. "All the same, he's the chap who done it," said he. "I expect he's got her up at his cabin on Otter Brook."

"Look here, November," I said. "You tell me Hank Harper is in the kidnapping business, and I believe you, because I've never known you speak without solid facts behind you; but I think you owe me the whole yarn."

Joe pulled out his pipe. "All right, Mr. Quaritch. We've some time to put in, anyway, before we need start to go to Harper's, and I'll spend the time in showing you how I lit on Hank. To begin at the beginning. There are two of them. One's this man Harper. I don't know who the other is, and it don't much matter. If we find Harper, we find his partner. Well, Miss Virginny was fishing when they stole down upon her and carried her off. I've already told you what happened until they took to the canoe. They paddled across the lake and the two men got out, leaving Miss Virginny in the canoe to paddle herself round and land elsewhere."

"But surely she could have escaped," I cried.

"She was under their rifles, and had to do exactly what she was ordered. I found where she'd landed, and followed her tracks to that little waterfall stream, and it was there I found the golden hair. So far, you see, everything fitted in together as good as the jaws of a trap, and the message on the bit of paper about a ransom carried it further on. So did the talk we had with Harper—it must have been him did the speaking—at Black Lake. When I knocked up Planx's revolver, I was wonderful sorry to have to do it, but a promise is a promise, and he'd passed his word for a safe-conduct. After, when my eyes fell upon the trail left by Harper's partner, I knew I never done a better act in my life."

"Explain, Joe!"

"That trail showed me I'd been wrong in my notions of the business, wrong from beginning to end."

"Wrong? Why, as you said yourself, it fits in all along."

"Did you take any notice of that trail?" inquired Joe.

"It seemed an ordinary trail, with nothing special about it."

"Was n't there? It give me a start, I can tell you, Mr. Quaritch! You see all the weight was in the middle of the moccasin. The heels and toes were hardly marked at all."

November looked at me as if expecting me to see the meaning of this peculiarity, but I shook my head.

"It meant that the foot inside the moccasin was a very little one, a good bit shorter than the moccasin."

"You can't mean—" I began.

"Yes," said Joe. "The second person at Black Lake was n't a man at all, but just Miss Virginny herself!"

"Well, if that was so, why she had the game in her hands then,—she had only to appeal to us,—to speak."

Joe interrupted me. "Hers was another sort of game. You see I'm pretty sure that Miss Virginny has kidnapped herself, or at any rate consented to be kidnapped!" He waited for this amazing statement to sink in before he continued. "The minute I come to that fact, I knew that my notion about her being covered with their rifles at the lake and all that was wrong, plumb wrong. She had just paddled round and joined the two men later; and then, when I come to think over it careful, I saw how I might raise the name of the man that was helping her."

"It does not look an easy thing to do," I said.

Joe smiled. "I lit out for Wilshere's camp, and asked the woman if there was anything of Miss Virginny's missing from her room. She said there was n't. Then I saw my way a bit. I was in the woods with Miss Virginny last year, and I know she's mighty particular about personal things. I don't believe she could live a day without a sponge and a comb, and most of all without a toothbrush—none of them hightoned gals can. Is n't that so?"

"Yes, that is so, but—"

"Well," went on November, "if she went of her own free will, as I was thinking she did—or else why did she come to Black Lake?—if, as I say, I was right in my notion, and she'd made out the plans and kidnapped herself, the man who was with her would be only just her servant, in a manner of speaking. And I was certain that one of the first things she'd do would be to send him to some store to buy the things she wanted most. She could n't get her own from Planx's camp without giving herself away, so she was bound to send Hank to hike out new ones from somewhere."

"What happened then?"

"I started in on the stores roundabout this country, and with luck I stepped into the big store at Lavette, and asked if any one had been buying truck of that kind. They told me Hank Harper. I asked just what. They said a hairbrush, a comb, a couple of toothbrushes, and some other gear. That was enough for me. They were n't for Mrs. Hank, who's a halfbreed woman, and don't always remember to clean herself o' Saturdays."

"I see," said I.

"The things was bought yesterday, so it all fits in, and there's no more left to find out but why Miss Virginny acted the way she has, and that we'll know before to-morrow."

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

It was well on towards ten o'clock that night before we reached Harper's cabin on Otter Brook. At first we knocked and knocked in vain, but at length a gruff voice demanded angrily what we wanted.

"Tell Miss Virginny Planx that November Joe would like a word or two with her."

"Are you drunk," shouted the man, "or only crazy?"

"I've tracked her down fair and square and I've got to see her."

"I tell you she is n't here."

"Let me in to make sure for myself."

"If a man comes to my door with a threat, I'll meet him with my rifle in my hand. So you're warned," came from the cabin.

"All right, then I'll start back to report to Mr. Planx."

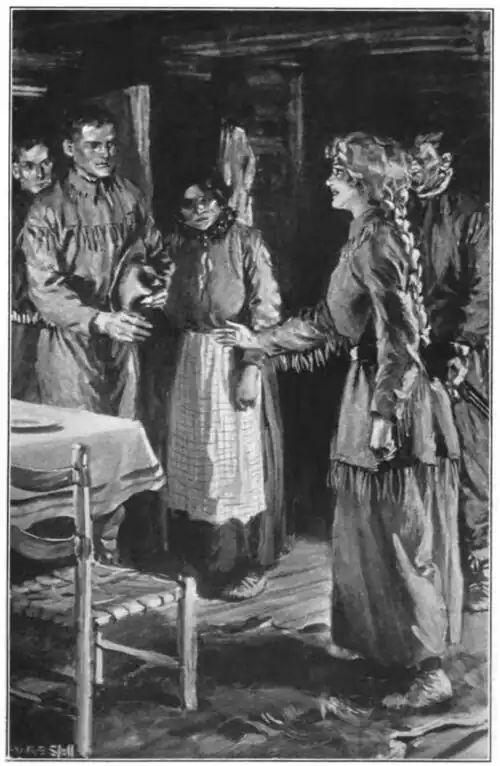

On the words the door opened and a vivid, appealing face looked out. "Come in, dear Joe," said a honeyed voice.

"Thank you, Miss Virginny, I will," said Joe.

We entered. A lamp and the fire lit up the interior of a poor trapper's cabin, and lit up also the tall slim form of Miss Virginny Planx. She wore a buckskin hunting shirt belted in to her waist, and her glorious hair hung down her back in a thick and heavy plait. She held out her hand to Joe with one of the sweetest smiles I have ever seen or dreamed of.

"You're not going to give me away, dear Joe, are you?" said she.

"You've given yourself away, have n't you, Miss Virginny?"

Virginia Planx looked him in the eyes, then she laughed. "I see that I have n't. But can I speak before this gentleman?"

Joe hastened to vouch for my discretion, while Hank Harper nursed his rifle and glowered from the background, where also one could discern the dark face of the half-breed squaw. But Miss Virginia showed her complete command of the situation.

"Coffee for these two, please, Mrs. Harper," she cried, and while we were drinking it she told us her story.

"You maybe heard of old Mr. Schelperg, of the Combine?" she began. "My father wanted to force me to marry him. Why he's fifty by the look of him, and . . . I'd much rather drown myself than marry him."

"There's younger and better-looking boys

She held out her hand to Joe around, I surmise, Miss Virginny?" returned November meaningly.

Virginia flushed a lovely red. "Why, Joe, it's no use blinding you, for you remember Walter Calvey, don't you?"

"Sure! So it's him. That's good. But I heard he was out of his business," said Joe with apparent simplicity.

"I must tell you all, or you won't understand what I did or why I did it. My father ruined Walter, because that would anyhow put off our marriage. Then, when the Schelperg affair came on and he gave me no rest, I could not stand it any longer. You see, he is so clever he would pay all my bills, no matter how heavy, but he never let me have more than five dollars in my pocket, so that I was helpless. I could never see Walter, nor could I hear from him, and all the time Schelperg was given the run of the house."

November was audibly sympathetic, and so was I.

"Then one day this notion came to me, I planned it all out, and got Hank to help. (I'd have asked you, dear Joe, if you'd been there.) Come now, Joe, you must see how good a pupil I was to you, and how much I remembered of your tracking, which I used to bother you to teach me."

"You're right smart at it, Miss Virginny!"

"I arranged the broken rod, and Hank and his brother carried me to the canoe, then they got out on the other side of the lake and I paddled up near to the rock by the waterfall, to put the police or whoever should be sent after me off my trail. I'm real hurt I did n't deceive you, Joe."

"But you did right through—till you come to Black Lake," Joe assured her.

"But you did not recognize me then?" she cried, "and I'd put on a pair of Hank's moccasins to make big tracks!"

November explained, and added the story of his dismissal by Planx.

"Well, it's lucky you were there, anyhow, or we'd have had poor Hank shot. That fixed me in my determination to get the money. I want it for Walter, I want to make up to him for all that my father has made him lose."

"So Mr. Calvey is in this, too?" said Joe in a queer voice.

"If you mean that he knows anything about it, you're absolutely wrong!" exclaimed Virginia passionately. "If he knew, do you think he'd ever take the money? It's going to be sent to him without any name or clue as to where it comes from. Walter is as straight a man as yourself, November Joe!" she added proudly. "You know him and yet you suspected him!"

"I did n't say I did. I was asking for information," said Joe submissively. "But you have n't got the money yet."

"No! But I'll get it in time."

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

And in the end Miss Virginia triumphed. She received her ransom in full, and it is to be doubted if Mr. Planx ever had an idea of the trick played on him. And I'm inclined to think Mr. Walter Calvey is still in the dark, too, as to the identity of his anonymous friend. But two things are certain—Mrs. Virginia Calvey is a happy woman, and Hank Harper is doing well on a nice two hundred acre farm for which he pays no rent.