November Joe/Chapter 10

Chapter X

The Mystery of Fletcher Buckman

I was dozing. It seemed to me deep in the night. The train that November Joe and I had boarded late the previous evening on our return from a trip in Quebec was passing, with a rattle and a roar, between the woods which flank the metals, when suddenly there rang out shriek upon shriek, such as mark the top note of grief and human horror.

Upon the instant the whole sleeping-car awoke; half a dozen passengers sprang to the carpeted floor, surprise and consternation eloquent in their faces and attitudes.

"It's from that private car," cried some one. "Who's in it?"

A bearded man answered: "Fletcher Buckman and his wife."

"It was a woman's scream."

"We must see what's wrong."

The bearded man and two others ran down the corridor, and at that moment the conductor stepped inside the door and confronted them squarely.

"What's happened?" gasped a voice. "There's murder doing. Here, let's pass!"

The conductor's hard face checked them. "Bah! Mrs. Buckman's had a nightmare. That's all there's to it," he said roughly.

I knew that his words were mere invention. His next act made me even more certain, for he locked the door behind him, walked quickly through the car, paying no attention to the babble of questions, remonstrance, incredulity, and advice thrust upon him from all sides; and a minute later he reappeared with November Joe, who, scorning sleepers, was travelling in the car ahead.

As he passed, Joe whispered, "Come on." I followed, hastily pulling on my coat, for I had lain down dressed. We stepped out from the blaze of electricity into a cold, white light of dawn, against which the massed trees on either side loomed black and wet as the train steamed forward.

On the open platform between the cars the conductor said a few words to Joe: "I brought you along, November, for I want a witness, anyway."

Then we passed into electricity again as we entered the private car. It would be impossible to forget the sight that met us. Across the floor lay the figure of a woman; her face, showing out among folds of shining silk, was white as chalk, and, though she had lost consciousness, it was still drawn with terror.

But my eyes passed by her to the side of the car, where, close to the bed-place, the body of a man was dangling, hung by the neck to a stout brass hook.

I could see that he was thinnish, with a drooping mustache and outrageously bald. He lurched and swayed to the swaying of the train, but it was the dreadful pink head bobbing stiffly that lent the last touch of horror. He was dressed in orange-coloured pyjamas, and his bare heels beat a tattoo against the side-boarding of the bunk.

In a second we had cut him down; but as the rigid body sank its weight upon our arms, we knew that life must have left it some good while before.

"It's Fletch Buckman, sure enough," said the conductor; "and he's had time to stiffen. No hope, I reckon! . . . There's no doc on the cars, but we can get a couple of women to see to Mrs. Buckman. We'll start to carry her out of this right now, before she comes to. "

The conductor and I raised her in our arms, and within two minutes we had left her in kindly hands.

When we got back Joe was still engrossed in his examination of the body. He put up his hand to warn us back as we appeared at the door.

"Wait a bit," he said. "You can talk from there, Steve. You were saying—"

The conductor took up what was evidently the thread of the story he had been telling to Joe when he first called him. "As I was explaining to you, I heard the screech and looked in just as she dropped. I stepped over and got at Fletch, but I knew by the feel of him it was too late to try any reviving. Next I went for you—" He paused.

Joe made no reply.

"She slept in the little compartment beyond 'cause he always stayed up half the night working, and often slept in the bunk here, like he did to-night," continued the conductor. "Guess it's suicide, Joe." He was leaning forward and looking into the contorted dead face on the pillow of the bed.

"Come in now," said November abruptly, and passed into Mrs. Buckman's sleeping-room, from which a door opened to the rear platform of the car. While he was busy moving in and out, Steve, the conductor, went round, making his own observations.

And here I may as well give a slight description of the car. It was not a large one, but was comfortably fitted with a couple of armchairs and the bunk already mentioned. A rolled-up hammock for use in the hot weather was strapped against the panelling, and the hook which had upheld poor Buckman's body was intended for supporting one end of this hammock when slung.

To the left was an office bureau with writing materials upon it, also a typewriter and an open leather bag containing folded papers. There were windows on both sides of the car; but while the one on the left was still covered with its slatted shutter, the glass of the opposite windows was bare, and showed the dark night-cloud sinking in the west.

Steve uttered an exclamation, and I saw he was reading some words typed on a sheet of paper fixed in the machine. November, who was still standing by the side of the dead man, looked round. Steve crossed over to him.

"It's sure suicide, " he said; "though what made him do it, and he already a millionaire and likely to be richer every day, beats me!"

"Suicide," repeated Joe softly. "Why suicide?"

"That's his own belt he was hung up with," replied Steve; "there's his name on it. And better proof than that you'll find on the typewriter over there. You can read it for yourselves."

I joined Joe at the table. The upper part of the sheet of paper, which was still in the machine, held some nine or ten lines of a business letter; then, an inch or more below, a few words stood out upon the plain whiteness:—

"Heaven help me! I can bear it no longer!"

"That's the sort of slush they mostly write when they're waiting to jump off the edge of the world," remarked the conductor. "That settles it."

"That's so," said Joe. "Only it was n't Buckman wrote that."

"Who else could it be?"

"The man that hanged him."

The conductor gave a snort of laughter.

"Then you surmise that some one came in here and hanged Fletch Buckman?"

"Just that."

"O' course, Buckman consented to being hung!" jeered Steve.

"Buckman was dead before he was hung!" said November.

"What's that you're saying?" cried Steve.

"If you examine the body—" began Joe.

The conductor made a forward movement, but Joe caught his arm.

"Let's see the soles of your boots before you get tramping about too much. Steady, hold on to the table. Now!"

He studied the upturned sole for a minute.

"Huh!" said he. "Now come over to the body. Look at the throat. There is the mark of a belt. But see here." He indicated some roundish, livid bruises. "No strap ever made those. Those were made by a man's fingers. Buckman was throttled by a pair of mighty strong hands."

Steve looked obstinate.

"But he was hanging!" he argued.

"When he was dead, the murderer slung him up with his own belt. I expect he remembered the notion of suicide would come in convenient to give him a start, anyhow, so the man went to the typewriter and printed out those words. It was a right cute trick, and it came wonderful near serving its turn," Joe paused.

Steve raised an altered face.

"It's a cinch, I'm afraid," he admitted. "And a durned mean thing for me. The company'll fire me over this."

"When did you last see Buckman alive?" inquired Joe.

"At midnight. Just before we passed Silent Water Siding."

"Was he alone?"

"He was then; Mrs. Buckman had gone to bed. But he had been talking to a fellow 'bout half an hour before that—a man with a beard. I don't know his name."

"He's still on the cars; we have n't stopped since."

"Sure."

"Then he can wait while—"

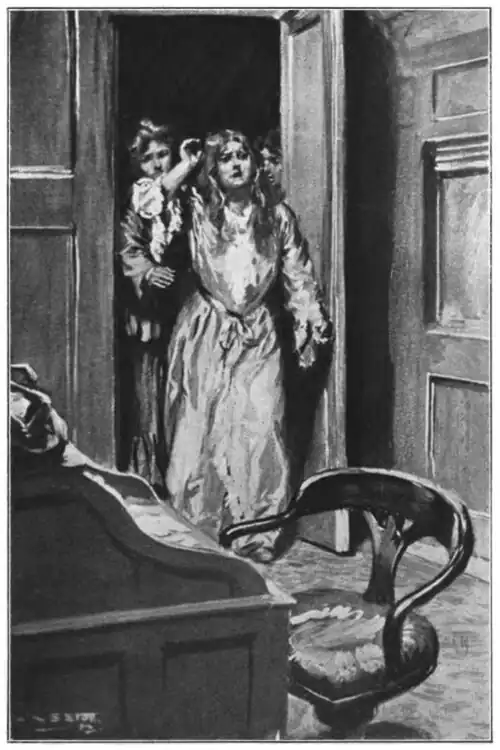

November was not destined to say more just then. The door behind us was wrenched open, and Mrs. Buckman stood there. At her shoulder I could see the peering faces of the women who had been attending on her.

"I tell you he was murdered, murdered!" she cried. "This talk of suicide is folly. He would never have killed himself—never!"

She was wild with grief, but the terror had gone from her face; she had only one thought now—to avenge her husband. And, indeed, she made a tragic figure—a slight woman, no longer young, held by sheer will against the shock of the hideous blow Fate had dealt her.

"Poor dear! Poor dear! She don't know what she's saying," murmured one of the women.

"Be silent! I do know! I tell you that my husband has been murdered. Won't any of you believe me?" She wrung her hands, clenching her fingers together. "Won't one of you believe me?"

November stepped forward.

"I do, ma'am," he said. "I've been looking—"

She made an effort to master herself.

"Tell me what you've seen. Don't spare me. He's dead, and all that is left to do is to find who killed him! It was murder! You know that."

"There's plenty signs of it," said Joe gently. "I was just going to look round, but perhaps you might care to answer me a few questions first?"

"Ask me anything! But, oh, send away those people!"

Joe glanced at Steve.

"Lock the door, and don't let anything be touched or disturbed," he said; then he led Mrs. Buckman into the farther compartment, away from the sight of the poor shape upon the bunk.

In a second he made a comfortable seat for her, but she would not take it; her whole body and soul seemed absorbed in the single desire.

Mrs. Buckman stood there "What have you to ask me?"

"Just what brought you and Mr. Buckman here. Where were you going? Where have you come from? And what are your suspicions? The whole story, whatever you can think of, nothing is too trifling."

In terse, rapid sentences, Mrs. Buckman gave us the following facts:—

"You have probably heard the name of Buckman before. Most people have. My husband was one of the greatest and most trusted oil experts in the States. He had large holdings in the Giant Oil Company. About a fortnight ago a situation developed which made it necessary for him to leave New York and come down to the Tiger Lily Oilfield. The Giant Company were thinking of buying it, or rather of buying a controlling interest in it. Before doing so they wanted a first-hand opinion, and it was suggested that my husband should travel down to look into the matter."

She glanced at November's intent face, and went on:—

"Perhaps you know that this line runs close to the Tiger Lily Eastern Section, so we had our private car attached and came along. That was on Thursday, a week ago. We had the car run onto a siding, and all the days since my husband has been hard at work. He finished the day before yesterday, but as there was no express earlier than this evening, we waited for it and just before dark our car was linked to this train.

"We dined together, and after dinner a man, Knowles, who was on the train, sent in to ask my husband to see him. My husband was much annoyed, for it appeared that Knowles had been manager of a large retail depot, from which he had been dismissed for some carelessness. However, my husband made it a rule to give personal interviews whenever he could, and he ordered Knowles to be sent along. As soon as he appeared, I went away, but I saw he was a big, sour-looking man in shabby clothes.

"I came into this compartment and began to read. For a good while only the murmur of their talking reached me, then a voice was raised, and I caught some words distinctly: 'You won't put me back? Think! I have a wife and children!' It was Knowles speaking. 'It is impossible, as you know,' said my husband. 'Giant Oil never reconsiders a decision.' 'Then look out for yourself!' Knowles shouted, and I at once opened the door. I was terrified, the man looked so threatening and bitter; but the instant I appeared he whipped round and went out of the car."

"Did Mr. Buckman tell you anything more about him?"

"Not much," she answered, with a sort of trembling breath, "for he was a little annoyed that I should have come in when I heard Knowles angry. But that was soon forgotten, and we sat talking for about an hour. At ten, as I was feeling tired, I said I would go to bed. My husband told me he had work to do which would keep him another couple of hours, and he would sleep in here so as not to disturb me."

"Do you know what work it was?"

"Yes, it was his report on the Tiger Lily Oilfield."

"The report that was to decide whether the Giant people would buy it or not?"

She made a movement of assent.

"I suppose it would have been worth a great deal to certain people if they could have found out the nature of that report?" said Joe.

"My husband told me that any one who could get knowledge of it in time could make a fortune."

"Can you tell me just how?"

"My husband explained that to me one day while we were down at the Tiger Lily. A month ago the shares of the Tiger Lily stood at eight dollars, but when rumours got about that the Giant Company meant to buy it they rose to twelve dollars, which is about the price they stand at to-day. My husband said that if his report were favourable the shares would jump to twenty, or even thirty, but that if it were unfavourable they would, of course, sink very low, indeed."

"I understand."

Mrs. Buckman went on: "Even I knew nothing of whether his decision was for or against the purchase. He never told me business secrets in case I should inadvertently let slip some information. I have no idea what line his report was to take."

"Was it not rather strange that Mr.

Then look out for yourself! Buckman should delay the writing of the report to the last moment? You have been days on the siding, and you tell me he had all the information ready the day before yesterday, and that you were only waiting for the express; yet he postponed writing his report until actually travelling late at night?" inquired November.

"I can explain that," replied Mrs. Buckman. "In his life my husband has had to deal with many secrets of great commercial value, so many that secrecy had become second nature with him, and it was one of his invariable rules never to put anything into writing until the last possible moment."

"There's reason in that," said Joe. "And now, did you hear anything after you went to bed?"

"I heard my husband working on the typewriter until I fell asleep. When I awoke I fancied I heard him moving about, and I called to him to go to bed. He did not answer, and as all was quiet I fell asleep again. If I had only got up then, I might have saved him!" She hid her face in her hands, but after a minute she mastered her emotion. "The next time I started up in a fright and turned on the light. It was long past three. I snatched at my wrapper and rushed into the next compartment. You know what I saw."

"One more question, ma'am, and then I'll trouble you no more. Have you any feeling as to who could have done this?" asked Joe, after a short silence.

"I don't know what to say—Knowles looked a desperate man. I heard his threat. But who are you, and why—"

Steve, who had hung in the doorway while this conversation was going on, now interposed to explain Joe, but she hardly seemed to heed. Before he concluded she put both her hands on November's arm.

"Remember, I'll spend the last cent I possess if you will only find that man! What are you going to do first?"

"I must examine the car. I have n't had time to do that thoroughly yet," said Joe. "But wait a minute. Look through his bag and see if the report of the Tiger Lily is in it."

It was not to be found. And after that, Steve took Mrs. Buckman away, for now that the strain of telling her story was over, she seemed as if she would collapse.

"There's a woman for you!" exclaimed Joe. "Say, Mr. Quaritch, I'll hunt that man for her till he drops in his tracks!"

Joe and I remained in the car, and he set about his examination in his peculiarly swift yet minute way. The carpet, the chairs, the table, the walls, all underwent inspection. He stood by the uncovered window for some time; he turned about the pens and paper on the table; he pored over the sheet in the typewriter on which the words were printed. At the end the only tangible result in my eyes was a collection of three matches, of which two were wooden and one of wax, three cigar stumps, and a little heap of fragments of mud.

His researches were nearing their conclusion when he caught sight of the knob of a drawer which had rolled into a dark corner under the bunk. He fitted this to a drawer of the desk. The finding of it evidently made him reconstruct his theories, for he went over the carpet once more, pausing a long time under the unshuttered window. Then he turned to the body and lastly fixed his attention on the bed. Behind the pillow lay a book called "Periwinkle," face downward.

"Read himself to sleep," said Joe. "Not much despair about that."

I nodded and made an inquiry.

"A carpet's mighty poor for tracking. Now, if this had happened in the woods, why, I'd be able to say more than that he—"

The conductor pushed open the door and stepped in hurriedly.

"Say, Joe, the evidence is getting to be the sure thing," he exclaimed.

Joe's grey eyes dwelt on the other's excited face for a moment.

"Against—"

"Knowles. Who else? He was seen creeping through the sleeping-car after midnight."

"Who saw him?"

"Thompson, the chap with the red head—next berth to this door. He saw Knowles slip by, but did n't think anything of it then."

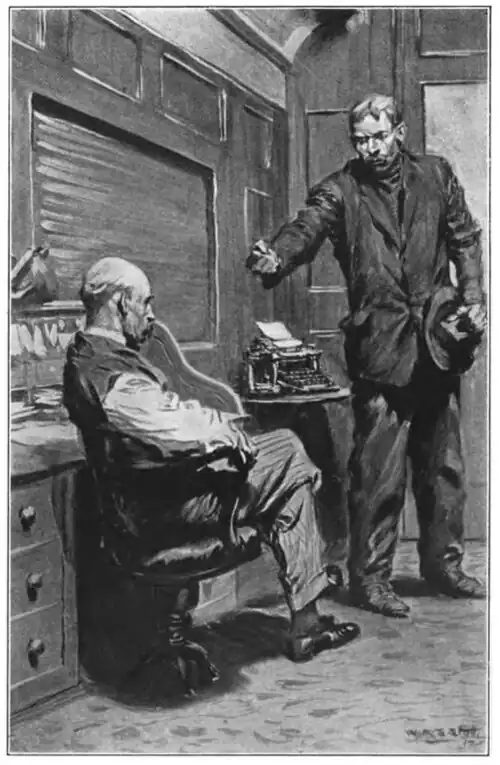

"Let's talk to Knowles," said Joe.

We were soon face to face with the suspected man. Mrs. Buckman's description, "sour-looking and shabby," fitted him very well. He appeared to be about fifty, with stooped but powerful shoulders, and he showed grey about the temples and in his stubble of beard. In the daylight he looked more than shabby, his whole person was unkempt and neglected. At first sight I mistrusted him, and every moment I spent in his company I liked him and his shifty, vindictive face worse. At the first it seemed he would not speak to any purpose, but at length Joe's bonhomie and tobacco thawed his reserve.

There were four of us in the uncomfortable privacy of the cook's galley.

"Yes," said Knowles, "it's true I was manager of the Treville depot of the Giant Oil three months ago, and that Buckman got me fired on some liar's evidence. I saw him last evening, and I told him what I thought of him."

"To be exact, you said: 'Look out for yourself?'" interposed Steve, the conductor.

"You were eavesdropping, were you?" Knowles said, looking a little startled. "I may have said something of that sort."

"But what about the second time you saw Buckman?" went on Steve.

"I did not see him a second time."

Here Joe spoke. "The truth is your best card," said he quietly.

Knowles glared like a trapped animal. "Why are you asking me all these questions?" he cried.

"Because Buckman was murdered, choked to death in the small hours of this morning."

Knowles gasped at the words. "Heavens! Is that true?"

"I guess it's no news to you!" snapped out Steve.

"What do you mean by that?"

"We know you passed along through the sleeper just before he was killed. You were seen. We can prove it."

Knowles had gone dead white. "I swear I never saw Buckman but once last night."

"Then what were you doing in the sleeper?"

Joe had stood silent during Steve's questioning, and at this Knowles turned to him.

"I'll tell you just the cold truth," he said. "I did go along. I was mad against Buckman, and I meant to see him and make another appeal."

"Then why did n't you see him?"

"Because I could n't. I tried, but the door of his car was locked."

"Locked?" cried Joe.

"Shut it, you dead-beat!" sneered Steve. "That yarn won't carry you, for I can prove it's a lie. The door were n't locked when I went along and found him dead. You won't tell me he got down to turn the key and then hung himself up again?"

"I'm speaking the truth," reiterated Knowles, "though you are all against me."

Then Joe astonished us.

"I'm not ag'in' you," said he. "I know as well as you do yourself that you did not murder Buckman."

"Bah! Then who did it?" cried the conductor.

"The man who locked the door and who was inside when Knowles went along."

Steve thrust out his lip. "Is that so? Well, until he's in handcuffs I'll make sure that Knowles here don't escape."

"All right," said Joe. "Say, Mr. Knowles, let me have a match."

Knowles pulled a box from his pocket.

"Now lay your hand flat on the table," went on Joe.

The large hand, with its grimed and jagged nails, was placed palm downwards for our inspection.

"Look at the thumbs," said Joe.

There was no more said until we were again alone with Steve.

"I'll undertake to smash any case you get up against Knowles, Steve, so as a jury of cottontail rabbits would n't convict him," said November.

"I'd like to see you do it!"

"Listen, then. There was two kinds of matches on the floor in the car—here they are." Joe spread them on his palm. "And here's one out of Knowles's box. This wax match was used by Buckman himself, these two wooden ones by the murderer. They're neither of them Knowles's brand, that's plain enough."

"That fact won't carry a jury."

"Not alone," said Joe. "But the next one will. You saw the sharp, broken nails on Knowles's hand. The thumbs had 'em nigh a quarter of an inch long. It's impossible to choke a man to death with nails that length and not tear and scratch the skin of the throat, and you saw for yourself that there is n't a mark on Buckman's throat but bruises only. That's a proof would go with any jury."

The conductor looked a little sheepish. "I'll give you best, Joe. But if it was n't Knowles, who in creation was it?"

"It was a man twenty years younger than Knowles, very active and strong. A superior chap, trims his nails with scissors, and is, at any rate, fairly educated. He is well acquainted with this line of railway. He boarded the car by the rear door when Buckman and his wife was asleep at some spot where the speed slows down. He was after the report on the Tiger Lily Oilfield. He was searching for it when Buckman woke and jumped at him."

"Why in thunder did n't Buckman give the alarm?"

"Because he tried to get to the bureau without the other seeing."

"To the bureau? What for?"

"For his revolver. He left it in the drawer. And he near got it, too. In the struggle the knob was tore off the drawer."

"But there was n't a revolver in that drawer. I had a look in it myself!"

"That's so; but it was there till the murderer took it out."

"What did he want it for if he'd got Buckman dead already?"

"A man don't likely hang himself if he's got a revolver handy that'll do the business more comfortably. The finding o' that revolver would, maybe, have spoiled the notion of suicide."

Steve nodded, and Joe continued:—

"Buckman put up a good fight, but the other was too strong for him. That fellow didn't mean to kill Buckman,—I think I can prove that later,—but he had to choke him to prevent his shouting. And when he found he'd done it too hard, like as not he had a bad five minutes. But he was full of cunning, and he hung him up as a blind. Then he locked the door and sat there in Buckman's chair and smoked one of Buckman's cigars."

"What?" exclaimed Steve. "With Buckman hanging there?"

"Sure! There was three cigar stumps. Two of them Buckman had smoked through a holder, but the end of the third was all chewed. I tell you the murderer sat there and smoked and thought out what he'd do, for Buckman's death was awkward in two or three ways. He sat there for nigh on twenty minutes, and now and again he'd go to the window that he'd slipped the shutter from and look out."

"Tracked him on the carpet?" inquired Steve, who was still a bit sore on the matter of Knowles.

Joe grinned significantly. "Yes, and found he had wet mud on his moccasins. That's how I first made sure it was n't you, Steve. Your soles were dry when I looked at them, and you have boots to your feet, anyway."

Steve's ejaculation cannot be set down here.

"He kep' going to the window," continued Joe, "'cos he wanted to locate the spot where he reckoned he'd slip off the car. I told you he knew the line well. Say, Steve, ain't there any curve where the engine slows down that you pass about one o'clock?"

"She slows down just before she gets to the big trestle bridge over the Shimpanny Lake."

Joe pondered a minute. "He jumped off there, and that means he had a bit of time to think out what he'd do. You see, his plan had n't worked out according to rule—to my way of thinking."

"How so?"

"I'll tell you all that later."

"You're a fair terror, Joe. You ought to have that chap in a net. Where did he board us, anyway?"

"Don't know. But it was n't long afore he killed Buckman, 'cos his moccasins had n't had time to dry. And that proves, too, that he wasn't hid on the cars since the last stop. Now what we've got to think about is catching him. I suppose I can get a fast engine at Seven Springs and go back down the line?"

"Sure," said Steve.

Twenty minutes later we arrived at Seven Springs, and in less than twenty minutes more November Joe and I, with a representative of the Provincial Police, were steaming back along the line. And we travelled at a speed which I believe was the greatest ever attempted over those metals. At length our engine thundered over the Shimpanny Lake and drew up. We descended, and began to search both sides of the line. A call from Joe brought us running to him.

"Here's where he jumped," he said. "See! He lost his footing and rolled down the bank."

At the spot where we were standing the railway line passed along the top of a high embankment, the south side of which was grown with a sprinkling of wild raspberry bushes. Beside the permanent way there were the deep prints of two moccasined feet; from them to the bottom of the bank a path had been ploughed through the broken canes to the foot of some spruces.

"He pitched down here like a sack," said Joe. "The train must have been going pretty fast—faster than he counted for. See here ag'in, the spruces. He got to his feet. Come on, there's his trail."

We followed it without difficulty for about fifty yards, and then we came upon a sapling spruce freshly cut down, about a foot above the ground; the head of it, with the little branches and leaves, lay scattered about.

Joe and the police trooper, whose name was Polloks, examined the little tree with its jagged cuts very carefully, November even lifting the chips of wood and bark which were spread about on the ground.

"What was he up to here, I wonder?" said Polloks. "He has n't made a fire."

"No," said Joe shortly, and hurried away upon the trail.

For another hundred yards the tracks were plain among the raspberry canes, then they climbed the embankment, and finally disappeared altogether.

Polloks swore. "He's done us here!" he cried. "He walked along the metals; no one can tell which way he's gone."

"Huh! He won't get shut of us," said November Joe, "not that way. Where's the nearest post-office on the line?"

"At Silent Water."

"You go and call up the engine, Polloks. It's Silent Water for us as fast as we can get there."

Polloks wasted no time, and once more we were flying along the line.

"The express passed Shimpanny Trestle at three-twenty this morning," shouted the trooper through the din of our travelling, "and it's seven now. Our man's got near four hours' start if he's ahead of us, but it's eighteen miles to Silent Water, so we may just nip him on the permanent way."

But, with the keenest lookout, we came in sight of no figure ahead of us before we reached Silent Water. It is a very small township, and we slipped through the depot so as to arouse no curiosity, and only stopped the engine a couple of hundred yards beyond to give us time to jump off. We hurried back to the post-office.

"Any fellow with his right arm in a sling been posting a letter here?" inquired Joe of the postmaster.

"None."

"Sure?"

"Been here all morning."

Joe pulled Polloks aside. "Quick! Work the telephone and have every post-office within twenty miles around watched. If a man with his right arm in a sling comes along to post a letter, arrest him. He'll be wearing cowhide moccasins, and a good size. But it was here I expected he'd aim for."

Polloks had hardly got to the telephone when Joe swung round, and, catching him by the shoulder, forced him down behind the counter out of sight. The next moment a tall young man with his arm in a rough sling opened the door of the post-office.

"Two-cent stamp," he said curtly to the postmaster.

The stamp was handed out, and as the stranger turned to go he held it between his lips, plunging his left hand into his pocket. I saw him pull out a long envelope, and at that instant Joe and Polloks leapt upon him.

"What in—" yelled the man.

But November Joe had seized the letter.

"Hold your man, Polloks. Look, this letter is addressed to the Giant Oilfields Head Offices. It is the Tiger Lily Report, and that is the murderer of Fletcher Buckman."

| • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

"It was sure easy," said Joe as we travelled up the line again, "from the moment I saw the mud stains on the carpet in Buckman's car. They were still wet, and when the murder was done we'd been going without a stop for three hours—time for any boots to dry in them heated cars. So it was n't any one on the train—that was clear.

"Then whoever done it must 'a' been young and active, or he could never board a train travelling at fifteen mile an hour, and he must have been fairly educated or he could n't have used the typewriter. Again, he must have been well acquainted with the railway."

"How could you tell that?"

"You remember that the blind was up off one window in Buckman's car. Again and again the murderer went to that window—I could tell by the tracks on the carpet. Now, why did he do that, unless he was looking for the place where he meant to jump off, and how could he recognize that place unless he knew the line?"

I thought I detected a flaw in November Joe's reasoning.

"Perhaps he was just waiting for the train to slow down," I said.

"No," replied Joe. "If he had been he'd never have lighted that cigar. The fact of his lighting that proves that he must 'a' known that he had twenty minutes to wait; and it proves that he was a mighty cool hand, too!"

I nodded.

"As for Knowles," continued Joe, "why, you heard more'n one reason why he was plumb out of it. The cigar and the matches and the wild-cat nails he carried."

"But how could you guess this fellow had his arm in a sling?"

"You mind that cut sapling near where he tumbled off the cars? He had n't took away two foot of it. What did he want a bit of spruce that length for? It would n't be to help him walk, or I'd 'a' guessed a sprained ankle. I fancied it might be for a splint. He would n't fall soft off the cars, you bet."

"But you said it was his right arm?"

"Look at the way he hacked the spruce! The clumsy way a man would with his left hand. That meant he'd damaged his right."

"But how did you know he'd want to post that letter, and post it at Silent Water? Why, it would have seemed more likely he'd make away across country."

"The post-office at Silent Water was a dead cert. I'll explain that, but you must go back a bit. You see, that chap only meant to get a forward look-in at the report; his game and the game of the people he was working for was to forestall the rest of the world in knowing what Buckman's decision was. He did not want to kill Buckman, only matters turned that way. Then he had to take away the report, for it was n't a cent o' use to him until it was in the hands of the Giant Oil Company, and he had to get it there without any notion of its having been tampered with. His idea was to go back along the line and post it just where Buckman might have posted it himself. He trusted to the suicide dodge to hold up suspicion till he was through with his plan."

"But would the Giant Oil Company act on the report after hearing of Buckman's horrible death?" I argued.

"Why not?" said Joe. "All they'd think was he'd had it posted the night before, just as soon as he'd finished writing it. Yes, they'd 'a' acted on it, and this chap—I have n't got his name yet—would 'a' cleaned up a good many hundred thousand dollars!"

"By the way, Joe," I said. "Where is Buckman's report?"

Joe smiled. "On its way to Giant Oil by this. We mailed it."

"I wonder if it was favourable?"

"We could n't open it, you know, but the chap had a slip o' paper on him on which he'd written a telegraph message. Just one word—'Buy.' So I guess you can buy me fifteen shares in Tiger Lily as soon as you like, Mr. Quaritch," replied November. "I've got the money, for I trapped a silver fox last winter; this report'll maybe turn it into a gold one! You light out and buy some shares, too, and then maybe you'll make that trip to Africa we've so often yarned about. I'd like to shoot one of them lions. I see one once to a fair, near Levis, and you could hear him roaring out on the ferry halfway across to Quebec. I'd sure like to copy 'T.R.,' and down one of they."