Nature in a City Yard/Chapter 4

IV

WINTER

EXCEPT for its varying physical geography, the back yard gets little attention in winter. Perhaps it deserves to be looked at oftener, for snow will drift in fantastic shapes, and we have miniature mountain-ranges and plateaus, and, in thaws, an extensive system of lakes. Our arctic scenery does not stay arctic. Its gloss and whiteness are dulled by smoke and dust, and the feet of birds and cats, by dropped leaves of withering plants, and by the undetected yet pervading foulness of city air. And in the longest, sharpest winter the juices of the grass and shrubs are not frozen, like the surface moisture, but are merely locked in the roots until the sun calls them into the stalks, or makes new leaves to busy themselves in, when March arrives.

When it is not covered with snow, or, rather, dappled with it, the yard is dull and brown, at first glance, and the white carpet is pierced by dry stems and ragged leaves. But go out with green in your mind, and it is surprising what an answer of green you get from the earth. The kalmia’s leaves are leathery, yet they keep a lot of color, and its stalks are tipped with stout buds, securely waiting the vernal equinox. The honeysuckle—indispensable plant—retains its foliage; its shiny black berries drop first, the leaves taking a slaty hue, and finally bronzing into olive. Shreds of gourd-vine hang to the fence, and the long ropes of morning-glory on the house hold hundreds of their blossom-cups, mere stars; but the green has wholly died from them. The iris fades only after repeated nippings, and the chrysanthemum has to be told often that it is winter. After the first frosts I find that the chrysanthemums, salvia, bellis, hydrangea, petunia, verbena, alyssum, daisy, and dandelion stand it best. A pet dandelion bloomed after several frosts, and another one came into flower at Christmas, during one of the insipid winters that we have along the fortieth parallel.

But it is the grass that keeps its color best. After a succession of mild days it really grows, and under the top-dressing clover is often found to have started. Grass will become dry and brown in time, but the algæ on weed, especially on tree-trunks, never do so, They keep fresh and bright through every winter, and snow and rain serve only to intensify their color. Thoreau was nearly right when he said that it took a lichenist to see how a tree-trunk looked. He might have added—and an artist. The artist is the only one who sees things as they are. The rest of us see what we think ought to be there, and overlook many things equally important that are there.

Vegetation wants but a kindly hour to bring it up. On a February morning, in a calm between two blizzards, although it was by no means sultry, clover was found half an inch out of the earth; and three days later, in another mild spell, the warm warble of a bird was heard across the roofs. (Pity me that I don’t know what kind of a bird it was!) In mid-January, after a longish spell of cold, I have found fresh leaves of buttercup and bellis and dandelion under the mulch.

After heavy winter rains, followed by a quick freeze, the puddles crust over with ice, and the water, soaking into the earth, —partially evaporating, too, perhaps,—leaves this ice a mere shell over nothing. Where the freezing has been irregular because of wind, spiky ridges a foot and more in length—true crystals, doubtless—may be traced in the ice like Cuphic symbols on a rock. And I wonder if we have got nothing out of ice and drifts and icicles for our arts in all these years. No Gothic pendents, think you? No roofs, and eaves, and pediments? No tessellations? No mural ornaments? Art has never touched the delicacy of the frost-ferns on the window, nor reached the splendor of the Jungfrau's silver dome; but out of these things beauty may have grown into stone without even conscious effort by the architect. They ask perpetuation, these melting glories, and his is the art to keep or convert them. Architecture appeals to more than the eye alone. It satisfies the sense for substance, greatness, permanence, such as snow hints in shining shadow. In that the builder’s art is like nature. But for this solidity, the stage palace of canvas would serve our minds as well as Durham Cathedral or the Chicago Fair.

One advantage in our yard is that it gives access to the shrillest, coldest winds of winter. And though it is a mournful music, it is likewise of a brave, romantic kind. True comfort of indoors is complete only with a gale brattling at the windows. Draw the curtains, stir the fire, see the family bestowed for the night; let there be no burning of garish and vulgar gas, no dusty, choking furnaces, no thrice-abominable cracking, clinking, smelling, and roasting of steam radiators; have at your elbow a mug of something cold and bubbling, or hot and fragrant, as your taste directs; if there are no women at home, or if this is your den, have a cigar if you like; then snuggle into your easy-chair and enjoy the concert. The booming, the gusts, the eldritch skirling,—I don’t know what that means, but it sounds well and windy,—the whispering and moaning, the shaking of blinds and casings, the singsong of the air’s voice, are inspiring. It is Wagner night when a zephyr achieves forty miles an hour. Those threatening sounds tell of far, cold wastes, of manful souls battling homeward on the sea, of men in lonely places doing duty in the cold; and the fire to which we go for pictures yields up a story of heroism in the mountains, on the ocean, on the plains, that the wind accompanies, and that makes us glad to be of the precious human race. Learn to love the wind. It is free, wild, pure, and strong. It is a voice that never sings false. You are never small when you listen to it.

And the colder outside the cosier within. There is experience enough of cold and storm to be had through the windows to satisfy a good many. Yet a man likes to find that the thermometer in his yard has gone higher in summer and lower in winter than the thermometers of his neighbors. It makes his place adventurous, and he doubtless feels that he is an object of interest or sympathy.

One blessed state of winter is the quiet and late morning hours it imposes on our neighbors’ fowls. They seldom harry us with visits after worms and seeds, but the cocks proclaim their waking at seasons when you do not wish to be apprised of it. It is one of the plagues of city life that you are thrown so close against disagreeable events. The authorities recognize but one nuisance,—that which offends the smell,—inasmuch as it argues offense to physical health. When a man boils bones or makes fertilizers, his neighbors stop the work, even going across the borders of his property to do it; but he is safe to offend the sight in any way he likes, and he can take strange liberties with our ears. The barking dog, the singing ass, the screeching parrot, the shrilling cat, the crowing cock, and the boy learning to play on the violin it is hard to surpass.

There was one bird who used to crow for about forty minutes, beginning at one o’clock in the morning. The wrath engendered by these solos kept me awake until three, and shortly after that hour he resumed for another half-hour or so. At five he began to crow in serious earnest for the day. And that pesky bird would go to bed while the sun was an hour high, in order to keep his voice fresh. His owner was one of the Seven Sleepers, and had never heard him; but by reason of an order from the health board and a police visit, I convinced him that the rest of us did, and the warbler was shut up after dark forthwith, He had escaped no end of stones, coal, and kindling that had been hurled at his voice during the night by people who went to bed at midnight and slept with their windows open.

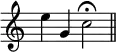

Not all roosters are so offensive. I have heard the crow of one that was a long, wailing note like the howl of a dog. No two voices are alike, be it of men or birds; no two faces, no two minds, no two creatures, crystals, flowers, or petals. Nature’s infinite variety in unity! Somewhere, too, in the dawn, a cock called the hour in a trumpet-blast, definitely musical, thus:

and redeemed himself by that performance; for, of all futilities in nature, the harsh note of the domestic cock is most needless. There is an utter want of meaning in his tune. Inanimate things are sometimes more agreeable than he, and are less depraved than philosophers would have us think. I heard from our yard a farm-wagon grating and grinding along a street-car track on a frosty day, and the sound was in thirds and fifths, like two notes of a bugle.

How would it do, now, to remove the rooster’s vocal cords, if he has any, and by dint of stirpiculture supplant the existing species by a crowless race? Surely, greater wonders than this have been accomplished without man's help; and I often wonder why the cock, being a low-roosting bird, reached easily by prowling foxes and the like, did not long ago cease to advertise his whereabouts. Far back there was a reason for his noise, or he would n’t have made it. It was evolved from the grunt or hiss of some wallowing lizard, his remotely great grandfather. Now that he has taken to living with us, let us encourage him to forget it. They say that evolution hardly explains the wonderful adaptability and economy of everything to its function. Why not? The most direct is the most economic; and evolution never goes roundabout. As soon as man got fairly planted on his hind legs, his tail shriveled and fell off.

Perhaps, though, the rooster does not want to evolve, does not want to be peaceable, does not want to lose his voice. He may take the same joy in using it that Reginald McGonigle takes in using his, or that the thugs do in New York when they lift theirs in blasphemy and foulness, proud of their ability to create attention, to shock where they cannot win respect. Well, there is a foundation rightness in this evil way of theirs, Old Adam is only the old animal. It does not do to be too civilized, Extremes meet. The meeting-place of high culture and abject poverty are the asylum and the graveyard. Society tells us that we are helpless without civilization. Yes; it has made us so, Left alone from birth, if we did not starve early we should be “more destitute than a brute,” especially as we are without any of the wings, claws, teeth, hair, feathers, and prehensile tails that put the eagle, the tiger, the monkey above us in the contest with nature, Do we not, then, as we get older and realize our loss, want to begin over again, and recover some of these brute advantages?

But, ah! which one of our acquired benefits are we willing to give up for more muscle, or for budding wings? The habit of house-building? The art of cookery? The daily paper? Hm! Something of our talk? Some of that vexing and variant fluid we call mind? Or the gift of imagination? Not the last, I think. That is the utmost of our evolution. It is the agency that lets us be other, greater, happier than we are. Life in the country might be as base as life in town if it were not for imagination, How much we owe to it, for how little we have in life, and death, that is tangible! A little while ago I heard a whistle—on a tug-boat in the river, most likely, for I hear it once a week at least; and whenever it sounds across the three miles of roofs, I drop my pen, spade, book, or what not, and am far away for some happy minutes. Sounds have, for me, the suggestive and reminiscent force that many find in odors; so, this whistle being in my memory the same I heard on the night boat that took me on my first visit to the Catskills, I have the thrill of that trip all over again. It was before the time of mountain railroads, big hotels, land speculations, and “No trespassing” signs. It was in October, and the haunted hills were lonely and all mine. The two days I spent there were spent afoot,—I walked and climbed sixty miles,—and they were a revel in color and the pathetic fragrance of fallen leaves. So the tug whistle dispels gloom, soothes overwrought nerves, obliterates meaner sounds, and comes like a call blown by fays and fauns of the crimson hills. It fills the world with romance, for it is one of the few privileges of life in the city that there is this much to take one out of it.

And it is one of the sorrows of that same life that there is so little winter during the cold months. The snow that ought to be used for sleighing, and for snow-balls to cast against the pot-hats and tiles of dignified citizens, is trampled and fouled and cleared away. Maybe when we have dismissed the horse from our service we shall be allowed to slide over the snowy streets in mechanically propelled sledges, and to take walks in parks and across vacant lots without sloshing through sweepings. There are few finer things than to be out of doors in wind and ugly weather. It satisfies our longing for fight. Thoreau says we must take long walks in storm and snow to keep our spirits up. “Deal with brute nature. Be cold and hungry and weary.” Hard advice for us cits. I suppose my three-mile wade to the office on the day of the great blizzard would not have counted with Thoreau; yet I protest I enjoyed it, and likewise the silence of the banked-up houses and blockaded streets for two days after. As to the yard, 1 do go there on winter evenings to see if any mistaken vegetable has stirred in the day’s sunshine, or if there are any new McGonigle tracks in the snow. If the yard were ten miles long I should not try to go to the end of it, unless it were moonlight. Walking in the small hours ever roads white with snow is one of the most peaceful yet exhilarating of experiences. As to cold, hunger, and tire, those states are excellent tonics, but poor company. Of course it is civilization that has made us cowardly, but there are few more wretched men than those, too proud to beg, who do not know at nightfall where they shall sleep or whether they shall eat.

The life of a yard writes itself large in new snow. It is occasionally clothes-line thieves, but mostly cats, and they wander about in our miniature wilderness, doubling on their tracks like the Israelites, as if to see how much ground to cover when there is not much to be covered. Sparrows, too, and pigeons occasionally descend and leave their starry footprints on the white. Why is it that the sparrows, which in other seasons fight and travel in knots of three or four, or go about singly, appear so often in cold weather in flocks of a hundred? Is it that each is afraid the others will get something to eat, and he—the thief!—not be on hand to fight his share away from them? There is a fine of one hundred dollars in New York State for feeding an English sparrow. It is not needed.

Perhaps if we had more patience with this rascal of a bird, he would exhibit some respectable qualities. Anyway, he would show character. There is no chance to show that when one is being “shooed” out of a doorway. Every animal has an individuality as marked as that of a human being. Take cats. Take all of ours, if you like, and don’t return them. But just take the case of cats. Their facial differences are considerable, when you look for them, and they often wear a deceptive countenance. Our Skimplejinks has a surprised and distant aspect, yet he gambols out to meet me in the morning, like a dog, and runs up my trousers and coat to my shoulder. When a boot is shied toward him along the floor, he shoots straight into the air, like a bucking bronco, and as high. I know two kittens of the same family: one a seraphic-looking youngster with a pretty face, soft fur, and contemptible disposition; the other a vagrom brute with coarse gray hair streaked with black, a vulgar countenance, and marked courtesy and consideration. The tramp will accept a bone thankfully, and in teasing for more will pat you softly to draw your attention, while the seraph spits at everything before eating it, and once, when I offered my finger coated with gravy for him to clean, he bit it instead.

It is pleasant to find that most people esteem animals, even when they are hunters and gourmets and wearers of ornamented bonnets, and prefer them dead. Thoreau says he likes the brutes because they never talk nonsense, are never foolish, vain, pompous, or stupid. How about a parrot, an ostrich, a peacock, a horse, a hen? They make capital companions, when they condescend to associate with us, and are always interesting, for they never lay bare their thoughts to us. They are full of surprises, Why does the horse bolt furiously up the street and kill several of us if, for the twentieth time in a week, he sees a harmless piece of paper blown about the pave? And why does Arthur, our dog, wail and howl when I play the “Moonlight Sonata,” though I play everything else as badly, or worse? Yet he comes to lie on my feet when I open the piano. And cats are as freakish as the weather. And there ’s our canary. He will not bathe unless his tub is put into his cage while it is hanging. Set it on the table, and he refuses to wet his feet.

The first snow is always an event even in town, Winter has really come, and the almanac is right. Even those who do not regard the seasons or look at the sky have this fact forced on them: that something is under foot that was not there yesterday. A company of gentlemen, passing as the flakes began to fall, showed that they were not wholly out of touch with nature.

Said one, “I ’Il be ——— ——— if it ain’t snowing!”

Another replied, “What the do I care if it is snowing?” Then, in a tone of awakening interest, “Well, by ———, I ’Il be ——— ——— if it ain’t snowing!”

And the gentlemen continued their stroll.

Occasionally the plants show a surprising indifference to frost. A rosebud that appeared about the first of October was still awaiting encouragement from the sun in the middle of November. On Thanksgiving day I examined it again, but it had not budged. As a mild winter followed, I found no change in it. It remained a swollen, but never-bursting bullet of red. Finally I cut it and put it into a vase of water in the house, thinking that it might open in the warmth; but it slowly withered without opening a leaf or abating a jot of its toughness. After no less than six frosts the yarrow was as green as in August.

And we often go out to look at these survivals, that we may keep our minds green until the time of birds and buds comes around once more.