Microbe Hunters/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

PASTEUR

AND THE MAD DOG

I

Do not think for a moment that Pasteur allowed his fame and name to be forgotten in the excitement kicked up by the sensational proofs of Koch that microbes murder men. It is certain that less of a hound for sniffing out microbes, less of a poet, less of a master at keeping people wide-eyed with their mouths open, would have been shoved off into a fairly complete oblivion by such events—but not Pasteur!

It was in the late eighteen-seventies—Koch had just swept the German doctors off their feet by his fine discovery of the spores of anthrax—that Pasteur who was only a chemist, had the effrontery to dismiss with a grunt, a shrug, and a wave of his hand, the ten thousand years of experience of doctors in studying and fighting diseases. At this time, in spite of Semmelweis, the Austrian who had proved child-bed fever was contagious, the Lying-In hospitals of Paris were pest-holes. Out of every nineteen women who went hopeful into their doors, one was sure to die of child-bed fever, to leave her baby motherless. One of these places, where ten young mothers perished in succession, was called the House of Crime. Women hardly dared to trust themselves to the most expensive physicians; they were beginning to boycott the hospitals. Large numbers of them—with reason—no longer cared to risk the grim danger of having babies. Even the doctors themselves—accustomed though they were helplessly but sympathetically to preside at the demise of their patients—even the physicians themselves, I say, were scandalized at this dreadful presence of death at the birth of new life.

One day, at the Academy of Medicine in Paris, a famous physician was holding an oration, with plenty of long Greek and elegant Latin words, on the cause—alas, completely unknown to him—of child-bed fever. Suddenly one of his learned and stately sentences was interrupted by a voice bellowing from the rear of the hall:

"The thing that kills women with child-bed fever—it isn't anything like that! It is you doctors that carry deadly microbes from sick women to healthy ones . . . !" It was Pasteur who said this; he was out of his seat; his eyes flamed excitement.

"Possibly you are right, but I fear you will never find that microbe" The orator tried to start his speech again, but by this time Pasteur was charging up the aisle, dragging his partly paralyzed left leg behind him a little. He reached the blackboard, grabbed a piece of chalk and shouted to the annoyed orator and the scandalized Academy:

"You say I will not find the microbe? Man, I have found it! Here’s the way it looks!" And Pasteur scrawled a chain of little circles on the blackboard. The meeting broke up in confusion.

Pasteur was in his late fifties now, but he was still as impetuous and enthusiastic as he had been at twenty-five. He had been a chemist and an expert on beet-sugar fermentations, he had shown the vintners how to keep their wines from spoiling, he had rushed from this job into the saving of sick silkworms, he had preached the slogan of Better Beer for France and had really made the French beer better; but during all these hectic years while he was doing the life work of a dozen men Pasteur dreamed about the tracking down of microbes that he knew must be the scourges of the human race, the authors of disease.

Then suddenly he found Koch had done the trick ahead of him. He must catch up with this Koch. "Microbes are in a way mine—I was the first to show how important they were, twenty years ago, when Koch was a child . . ." you can imagine Pasteur muttering. But there were difficulties in the way of his catching up.

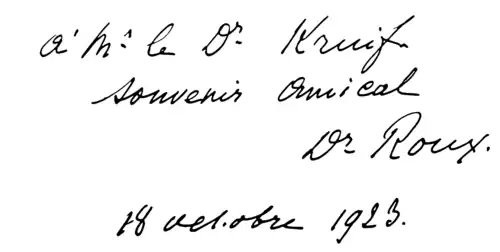

In the first place, Pasteur had never felt a pulse or told a bilious man to stick out his tongue, it is doubtful if he could have told a lung from a liver, and it is certain that he did not know the first thing about how to hold a scalpel. As for those cursed hospitals—phew! The smell of them gave him nasty feelings at the pit of his stomach, and he wanted to stop his ears and run away from the moans that floated down their dingy corridors. But presently—it was ever the way with this unconquerable man—he got around his medical ignorance. Three physicians, Joubert at first, and then Roux and Chamberland became his assistants; youngsters they were, these three, radicals who were Bolshevik against ancient idiotic medical doctrines. They sat worshiping Pasteur at his unpopular lectures in the Academy of Medicine, believing every one of his laughed-at prophecies of dreadful scourges caused by sub-visible bugs. He took these boys into his laboratory and in return they explained the machinery of animals' insides to Pasteur, they taught him the difference between the needle and the plunger of a hypodermic syringe and convinced him—he was very squeamish about such things—that animals like guinea-pigs and rabbits hardly felt the prick of the syringe needle when he injected them. Privately these three men swore to be his slaves—and the priests of this new science. . . .

Nothing is truer than that there is no one orthodox way of hunting microbes, and the differences between the ways Koch and Pasteur went at their work are the best illustrations of this. Koch was as coldly logical as a text-book of geometry—he searched out his bacillus of tuberculosis with systematic experiments, and he thought of all the objections that doubters might make before such doubters knew that there was any thing to have doubts about. Koch always recited his failures with just as much and no more enthusiasm than he did his triumphs. There was something inhumanly just and right about him and he looked at his own discoveries as if they had been those of another man of whom he was a little over-critical. But Pasteur! This man was a passionate groper whose head was incessantly inventing right theories and wrong guesses—shooting them out like a display of village fireworks going off bewilderingly by accident.

Pasteur started hunting microbes of disease and punched into a boil on the back of the neck of one of his assistants and grew a germ from it and was sure it was the cause of boils; he hurried from these experiments to the hospital to find his chain microbes in the bodies of women dying with child-bed fever; from here he rushed out into the country to discover—but not to prove it precisely—that earthworms carry anthrax bacilli from the deep buried carcasses of cattle to the surface of the fields. He was a strange genius who seemed to need the energetic, gusto-ish doing of a dozen things at the same time—more or less accurately—in order to discover that grain of truth which lies at the bottom of most of his work.

In this variety of simultaneous goings-on you can fairly feel Pasteur fumbling at a way of getting ahead of Koch. Koch had shown with beautiful clearness that germs cause disease, there is no doubt about that—but this isn't the most important thing to do . . . this is nothing, this proof, the thing to do is to find a way to prevent the germs from killing people, to protect mankind from death! "What impossible, what absurd experiments didn't we discuss," said Roux long after this distressing time when Pasteur was stumbling about in the dark. "We would laugh at them ourselves, next day."

To understand Pasteur, it is important to know his wild stabs and his failures as well as his triumphs. He had not the precise methods of growing microbes pure—it took the patience of Koch to devise such things—and one day to his disgust, Pasteur observed that a bottle of boiled urine in which he had

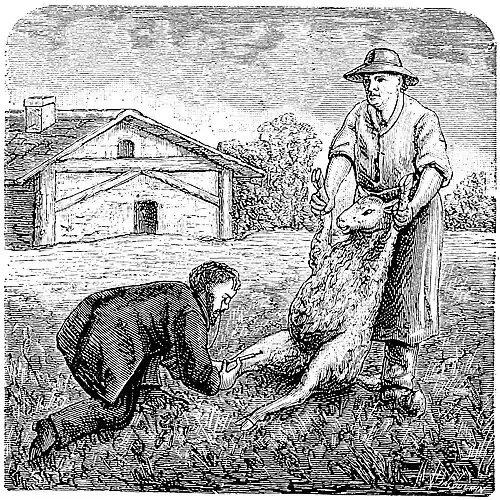

VACCINATING SHEEP FOR ANTHRAX

planted anthrax bacilli was swarming with unbidden guests, contaminating microbes of the air that had sneaked in. The following morning he observed that there were no anthrax germs left at all; they had been completely choked out by the bacilli from the air.

At once Pasteur jumped to a fine idea: "If the harmless bugs from the air choke out the anthrax bacilli in the bottle, they will do it in the body too! It is a kind of dog-eat-dog!" shouted Pasteur, and at once he put Roux and Chamberland to work on the fantastic experiment of giving guinea-pigs anthrax and then shooting doses of billions of harmless microbes into them—beneficent germs which were to chase the anthrax bacilli round the body and devour them—they were to be like the mongoose which kills cobras. . . .

Pasteur gravely announced: "That there were high hopes for the cure of disease from this experiment," but that is the last you hear of it, for Pasteur was never a man to give the world of science the benefit of studying his failures. But a little later the Academy of Sciences sent him on a queer errand, and on this mission he stumbled across a fact that gave him the first clew to a genuine, a remarkable way of turning savage microbes into friendly ones. It was an outlandish plan he began to devise, to dream about, of turning living microbes of disease against their own kind, so guarding animals and men from invisible deaths. At this time there was a great to-do about a cure for anthrax, invented by the horse doctor, Louvrier, in the Jura mountains in the east of France. Louvrier had cured hundreds of cows who were at death's door, said the influential men of the district: it was time that this treatment received scientific approval.

II

Pasteur arrived there, escorted by his young assistants, and found that this miraculous cure consisted first, in having several farm hands rub the sick cow violently to make her as hot as possible; then long gashes were cut in the poor beast's skin and into these cuts Louvrier poured turpentine; finally the now bellowing and deplorably maltreated cow was covered—excepting her face!—with an inch thick layer of unmentionable stuff soaked in hot vinegar. This ointment was kept on the animal—who now doubtless wished she were dead—by a cloth that covered her entire body.

Pasteur said to Louvrier: "Let us make an experiment. All cows attacked by anthrax do not die, some of them just get better by themselves; there is only one way to find out, Doctor Louvrier, whether or no it is your treatment that saves them."

So four good healthy cows were brought, and Pasteur in the presence of Louvrier and a solemn commission of farmers, shot a powerful dose of virulent anthrax microbes into the shoulder of each one of these beasts: this stuff would have surely killed a sheep, it was enough to do to death a few dozen guinea-pigs. The next day Pasteur and the commission and Louvrier returned, and all the cows had large feverish swellings on their shoulders, their breath came in snorts—they were in a bad way, that was very evident.

"Now, Doctor," said Pasteur, "choose two of these sick cows—we'll call them A and B. Give them your new cure, and we'll leave cows C and D without any treatment at all." So Louvrier assaulted poor A and B with his villainous treatment. The result was a terrible blow to the sincere would-be curer of cows, for one of the cows that Louvrier treated got better—but the other perished; and one of the creatures that had got no treatment at all, died—but the other got better.

"Even this experiment might have tricked us, Doctor," said Pasteur. "If you had given your treatment to cows A and D instead of A and B—we all would have thought you had really found a sovereign remedy for anthrax."

Here were two cows left over from the experiment, beasts that had had a hard siege of anthrax and got better from it: "What shall I do with these two cows?" pondered Pasteur. "Well, I might try shooting a still more savage strain of anthrax bacilli into them—I have one family of anthrax germs in Paris that would give even a rhinoceros a bad night."

So Pasteur sent to Paris for his vicious cultivation, and injected five drops into the shoulders of those two cows that had got better. Then he waited, but nothing happened to the beasts, not even a tiny swelling at the point where he had injected millions of poisonous bacilli; the cows remained perfectly happy!

Then Pasteur jumped to one of his quick conclusions: "Once a cow has anthrax, but gets better from it, all the anthrax microbes in the world cannot give her another attack—she is immune." This thought began playing and flitting about in his head and made him wool-gather so that he did not hear questions that Madame Pasteur asked him, nor see obvious things at which his eyes looked directly.

"How to give an animal a little attack of anthrax, a safe little attack that won't kill him, but will surely protect him. . . . There must be a way to do that. . . . I must find a way."

So it went with Pasteur for months and he kept saying to Roux and Chamberland: "What mystery is there, like the mystery of the non-recurrence of virulent maladies?" He went about muttering to himself: "We must immunize—we must immunize against microbes. . . ."

Meanwhile Pasteur and his faithful crew were training their microscopes on stuff from men and animals dead of a dozen different diseases; there was a kind of mixed-up fumbling in this work between 1878 and 1880—when one day fate, or God, put a marvelous way to immunize right under Pasteur's lucky nose. (It is hard for me to give you this story exactly straight because all of the various people who have written about Pasteur tell it differently and Pasteur himself in his scientific paper says nothing whatever about this remarkable discovery having been a happy accident.) But here it is, as well as I can do, with certain gaps that I have had to fill in myself.

In 1880, Pasteur was playing with the very tiny microbe that kills chickens with a malady known as chicken cholera. Doctor Peronçito had discovered this microbe, so tiny that it was hardly more than a quivering point before the strongest lens. Pasteur was the first microbe hunter to grow it pure, in a soup that he cooked for it from chicken meat. And after he had watched these dancing points multiply into millions in a few hours, he let fall the smallest part of a drop of this bug-swarming broth onto a crumb of bread—and fed this bread to a chicken. In a few hours the unfortunate beast stopped clucking and refused to eat, her feathers ruffled until she looked like a fluffy ball, and the next day Pasteur came in to find the bird tottering, its eyes shut in a kind of invincible drowsiness that turned quickly into death.

Roux and Chamberland nursed these terrible wee microbes along carefully; day after day they dipped a clean platinum needle into a bottle of chicken broth that teemed with germs and then carefully shook the same still-wet needle into a fresh flask of soup that held no microbe at all—so day after day these transplantations went on—always with new myriads of germs growing from the few that had come in on the moistened needle. The benches of the laboratory became cluttered with abandoned cultures, some of them weeks old. "We'll have to clean this mess up to-morrow," thought Pasteur.

Then the god of good accidents whispered in his ear, and Pasteur said to Roux: "We know the chicken cholera microbes are still alive in this bottle . . . they're several weeks old, it is true . . . but just try shooting a few drops of this old cultivation into some chickens. . . ."

Roux followed these directions and the chickens promptly got sick, turned drowsy, lost their customary lively frivolousness. But next morning, when Pasteur came into the laboratory looking for these birds, to put them on the post-mortem board—he was sure they would be dead—he found them perfectly happy and gay!

"This is strange," pondered Pasteur, "always before this the microbes from our cultivations have killed twenty chickens out of twenty. . . ." But the time for his discovery was not yet, and next day, after these strangely recovered chickens had been put in charge of the caretaker, Pasteur and his family and Roux and Chamberland went off on their summer vacations. They forgot about those birds. . . .

But at last one day Pasteur told the laboratory servant: "Bring up some healthy birds, new chickens, and get them ready for inoculation."

"But we only have a couple of unused chickens left, Mr. Pasteur—remember, you used the last ones before you went away—you injected the old cultures into them, and they got sick but didn’t die?"

Pasteur made a few appropriate remarks about servants who neglected to keep a good supply of fresh chickens on hand. "Well, all right, bring up what new chickens you have left—and let's have a couple of those used ones too—the ones that had the cholera but got better. . . ."

The squawking birds were brought up. The assistant shot the soup with its myriads of germs into the breast muscles of the chickens—into the new ones, and into the ones that had got better! Roux and Chamberland came into the laboratory next morning—Pasteur was always there an hour or so ahead of them—they heard the muffled voice of their master shouting to them from the animal room below stairs:

"Roux, Chamberland, come down here—hurry!"

They found him pacing up and down before the chicken cages. "Look!" said Pasteur. "The new birds we shot yesterday—they're dead all right, as they ought to be. . . . But now see these chickens that recovered after we shot them with the old cultures last month. . . . They got the same murderous dose yesterday—but look at them—they have resisted the virulent dose perfectly . . . they are gay . . . they are eating!"

Roux and Chamberland were puzzled for a moment.

Then Pasteur raved: "But don't you see what this means? Everything is found! Now I have found out how to make a beast a little sick—just a little sick so that he will get better, from a disease. . . . All we have to do is to let our virulent microbes grow old in their bottles . . . instead of planting them into new ones every day. . . . When the microbes age, they get tame . . . they give the chicken the disease . . . but only a little of it . . . and when she gets better she can stand all the vicious virulent microbes in the world. . . . This is our chance—this is my most remarkable discovery—this is a vaccine I've discovered, much more sure, more scientific than the one for smallpox where no one has seen the germ. . . . We'll apply this to anthrax too . . . to all virulent diseases. . . . We will save lives . . . !"

III

A lesser man than Pasteur might have done this same accidental experiment—for this was no test planned by the human brain—a lesser man might have done it and would have spent years trying to explain to himself the mystery of it, but Pasteur, stumbling on this chance protection of a couple of miserable chickens, saw at once a new way of guarding living things against virulent germs, of saving men from death. His brain jumped to a new way of tricking the hitherto inexorable God who ruled that men must be helpless before the sneaking attacks of his sub-visible enemies. . . .

Pasteur was fifty-eight years old now, he was past his prime, but with this chance discovery of the vaccine that saved chickens from cholera, he started the six most hectic years of his life, years of appalling arguments and unhoped-for triumphs and terrible disappointments—into these years, in short, he poured the energy and the events of the lives of a hundred ordinary men.

Hurriedly Pasteur and Roux and Chamberland set out to confirm the first chance observation they had made. They let virulent chicken cholera microbes grow old in their bottles of broth; they inoculated these enfeebled bugs into dozens of healthy chickens—which promptly got sick, but as quickly recovered. Then triumphantly, a few days later, they watched these birds—these vaccinated chickens—tolerate murderous injections of millions of microbes, enough to kill a dozen new birds who were not immune.

So it was that Pasteur, ingeniously, turned microbes against themselves. He tamed them first, and then he strangely used them for wonderful protective weapons against the assaults of their own kind.

And now Pasteur, with his characteristic impetuousness—after all it was only chickens he had learned to guard from death so far—became more arrogant than ever with the old-fashioned doctors who talked Latin words and wrote shot-gun prescriptions. He went to a meeting of the Academy of Medicine and with complaisance told the doctors how his chicken vaccinations were a great advance on the immortal smallpox discovery of Jenner: "In this case I have demonstrated a thing that Jenner never could do in smallpox—and that is, that the microbe that kills is the same one that guards the animal from death!"

The old-fashioned blue-coated doctors were peeved at Pasteur's appointing himself a god superior to the great Jenner; Doctor Jules Guérin, the famous surgeon, became particularly sarcastic about Pasteur making so much of mere fussings with chickens—and the fight was on. Pasteur, in a fury got up and shouted remarks about the utter nonsensicality of one of Guérin's pet operations, and there occurred a most scandalous scene—it embarrasses me to have to tell about it—a strange shambles in which Guérin, who was past eighty, rose from his seat and was about to fall on the sixty-year-old Pasteur. The old man aimed a wallop at Pasteur, but frantic friends jumped in and prevented the impending fisticuffs of these two men who thought they could settle the truth by kicks and blows and mayhem.

Next day the ancient Guérin sent his seconds to Pasteur with a challenge to a duel, but Pasteur, evidently, did not care to risk dying that way and he sent Guérin's friends to the Secretary of the Academy with this message: "I am ready, having no right to act otherwise, to modify whatever the editors may consider as going beyond the rights of criticism and legitimate defense." And so Pasteur once more proved himself to be a human being—if not what is commonly called a man—by backing out of the fight.

As I have told you before, Pasteur had a great deal of the mystic in him. Often he bowed himself down before that mysterious Infinite—he worshiped the Infinite when he was not clutching at it like a baby reaching for the moon; but frequently, the moment one of his beautiful experiments had knocked another little chunk off that surrounding Unknown, he made the mistake of believing that all mysteries had dissolved away. It was so now—when he saw that he could really protect chickens perfectly against a fatal illness by his amazing trick of sticking a few of their own tamed assassins into them. At once Pasteur guessed: "Maybe these fowl-cholera microbes will guard chickens against other virulent diseases!" and promptly he inoculated some hens with his new vaccine of weakened fowl cholera germs and then injected them with some certainly murderous anthrax bacilli—and the chickens did not die!

Wildly excited he wrote to Dumas, his old professor, and hinted that the new fowl-cholera vaccine might be a wonderful Pan-Protector against all kinds of virulent maladies. "If this is confirmed," he wrote, "we can hope for the most important consequences, even in human maladies."

Old Dumas, greatly thrilled, had this letter published in the Reports of the Academy of Sciences, and there it stands, a sad monument to Pasteur's impetuousness, a blot on his record of reporting nothing but facts. So far as I can find, Pasteur never retracted this error, although he soon found that a vaccine made from one kind of bacillus does not protect an animal against all diseases, but only—and then not absolutely surely—against the one disease of which the microbe in the vaccine is the cause.

But one of Pasteur's most charming traits was his characteristic of a scientific Phœnix, who rose triumphantly from the ashes of his own mistakes. When his imagination carried him into the clouds you find him presently landing on the ground with a bump—making clever experiments again, digging for good true hard facts. So it is not surprising to find him, with Roux and Chamberland, in 1881, discovering a very pretty way of taming vicious anthrax microbes and turning them into a vaccine. By this time the quest after vaccines had become so violent that Roux and Chamberland hardly had their Sundays off, and never went on vacations; they slept at the laboratory to be near their tubes and microscopes and microbes. And here, Pasteur directing them, they delicately weakened anthrax bacilli so that some killed guinea-pigs, but not rabbits, and others did mice to death, but were too weak to harm guinea-pigs. They shot the weaker and then the stronger microbes into sheep, who got a little sick but then recovered, and after that these sheep could stand, apparently, the assaults of vicious anthrax germs that were able to kill even a cow.

At once Pasteur told this new triumph to the Academy of Sciences—he had left off going to the Academy of Medicine after his brawl with Guérin—and he held out purple hopes to them that he would presently invent ingenious vaccines that would wipe out all diseases from mumps to malaria. "What is more easy," he shouted, "than to find in these successive viruses a vaccine capable of making sheep and cows and horses a little sick with anthrax without letting them perish—and so preserving them from subsequent maladies?" Some of Pasteur's colleagues thought he was a little cocksure about this, and they ventured to protest. Pasteur's veins stood out on his forehead, but he managed to keep his mouth shut until he and Roux were on the way home, when he burst out, speaking really of all people who failed to see the absolute truth of his idea:

"I would not be surprised if such a man were to be caught beating his wife!"

Make no mistake—science was no cool collecting of facts for Pasteur; in him it set going the same kind of machinery that stirs the human animal to tears at the death of a baby and makes him sing when he hears his uncle has died and left him five hundred thousand dollars.

But enemies were on Pasteur's trail again. Just as he was always stepping on the toes of physicians, so he had offended the high and useful profession of the horse doctors, and one of the leading horse doctors, the editor of one of the most important journals of horse doctoring, his name was Doctor Rossignol, cooked up a plot to lure Pasteur into a dangerous public experiment and so destroy him. This Rossignol got up with a great show of scientific fairness at the Agricultural Society of Melun and said:

"Pasteur claims that nothing is easier than to make a vaccine that will protect sheep and cows absolutely from anthrax. If that is true, it would be a great thing for French farmers, who are now losing twenty million francs a year from this disease. Well, if Pasteur can really make such magic stuff, he ought to be willing to prove to us that he has the goods. Let us get Pasteur to consent to a grand public experiment; if he is right, we farmers and veterinarians are the gainers—if it fails, Pasteur will have to stop his eternal blabbing about great discoveries that save sheep and worms and babies and hippopotamuses!" Like this argued the sly Rossignol.

At once the Society raised a lot of francs to buy forty-eight sheep and two goats and several cows and the distinguished old Baron de la Rochette was sent to flatter Pasteur into this dangerous experiment.

But Pasteur was not one bit suspicious. "Of course I am willing to demonstrate to your society that my vaccine is a life-saver—what will work in the laboratory on fourteen sheep will work on sixty at Melun!"

That was the great thing about Pasteur! When he prepared to take the rabbit out of the hat, to astonish the world, he was absolutely sincere about it; he was a magnificent showman and not below some small occasional hocus-pocus, but he was no designing mountebank. And the public test was set for May and June, that year.

Roux and Chamberland—who had begun to see animals that were strange combinations of chickens and guinea-pigs in their dreams, to drop important flasks, to lie awake injecting millions of imaginary guinea-pigs, these fagged-out boys had just started off on a vacation to the country—when they received telegrams that brought them back to their exciting treadmill:

COME BACK PARIS AT ONCE ABOUT TO MAKE PUBLIC DEMONSTRATION THAT OUR VACCINE WILL PROTECT SHEEP AGAINST ANTHRAX—L. PASTEUR.

Something like that read these wires.

They hurried back. Pasteur said to them: "Before the Agricultural Society of Melun, at the farm of Pouilly-le-Fort, I am going to vaccinate twenty-four sheep, one goat and several cattle—twenty-four other sheep, one goat and several other cattle are going to be left without inoculation—then, at the appointed time, I am going to inject all of the beasts with the most deadly virulent culture of anthrax bacilli that we have. The vaccinated animals will be perfectly protected—the not-vaccinated ones will die in two days of course." Pasteur sounded as confident as an astronomer predicting an eclipse of the sun. . . .

"But, master, you know this work is so delicate—we cannot be absolutely sure of our vaccines—they may kill some of the sheep we try to protect"

"WHAT WORKED WITH FOURTEEN SHEEP IN OUR LABORATORY WILL WORK WITH FIFTY AT MELUN!" Pasteur roared at them. For him just then, there was no such thing as a mysterious, tricky nature, an unknown full of failures and surprises—the misty Infinite was as simple as two plus two makes four to him just then. So there was nothing for Roux and Chamberland to do but to roll up their sleeves and get the vaccines ready.

The day for the first injections came at last. Their bottles and syringes were ready, their flasks were carefully labeled—"Be sure not to mix up the first and second vaccine, boys!" shouted Pasteur, full of a gay confidence, as they left the Rue d'Ulm for the train. As they came on the field at Pouilly-le-Fort, and strode toward the sheds that held the forty-eight sheep, two goats and several cattle, Pasteur marched into the arena like a matador, and bowed severely to the crowd. There were senators of the Republic there, and scientists and horse doctors and dignitaries, and hundreds of farmers; and as Pasteur walked among them with his little limp—it was however a sort of jaunty limp—they cheered him mightily, many of them, and some of them snickered.

And there was a flock of newspaper men there, including the now almost legendary de Blowitz, of the London Times.

The sheep, fine healthy beasts, were herded into a clear space; Roux and Chamberland lighted their alcohol lamps and gingerly unpacked their glass syringes and shot five drops of the first vaccine—the anthrax bacilli that would kill mice out leave guinea-pigs alive, into the thighs of twenty-four of the sheep, one of the goats, and half of the cattle. The beasts got up and shook themselves and were labeled by a little gouge punched out of their ears. Then the audience repaired to a shed where Pasteur harangued them for half an hour—telling them simply but with a kind of dramatic portentousness of these new vaccinations and the hopes they held out for suffering men.

Twelve days went by and the show was repeated. The crowd was there once more and the second vaccine—the stronger one whose bacilli had the power of killing guinea-pigs but not rabbits—was injected, and the animals bore up beautifully under it and scampered about as healthy sheep, goats and cattle should do. The time for the fatal final test drew near; the very air of the little laboratory became finicky; the taut workers snapped at each other across the Bunsen flames. Pasteur was never so appallingly quiet—and the bottle washers fairly jumped across the room to fill his growled orders. Every day Thuillier, Pasteur's new youngest assistant, went out to the farm to put his thermometer carefully under the tails of the inoculated animals to see if they had fever—but thank God, every one of them was standing up beautifully under the heavy dose of the vaccine that was not quite murderous enough to kill rabbits.

While the heads of Roux and Chamberland turned several hairs grayer, Pasteur kept his confidence, and he wrote, with his old charmingly candid opinion of himself: "If success is complete, this will be one of the finest examples of applied science in this country, consecrating one of the greatest and most fruitful discoveries."

His friends shook their heads and lifted their shoulders and murmured: "Napoleonic, my dear Pasteur," and Pasteur did not deny it.

IV

Then on the fateful thirty-first of May all of the forty-eight sheep, two goats, and several cattle—those that were vaccinated and those to which nothing whatever had been done—all of these received a surely fatal dose of virulent anthrax bugs. Roux got down on his knees in the dirt, surrounded by his alcohol lamps and bottles of deadly virus, and awed the crowd by his cool flawless shooting of the poisonous stuff into the more than sixty animals.

With his whole scientific reputation trusted to this one delicate test, realizing at last that he had done the brave but terribly rash thing of letting a frivolous public judge his science Pasteur rolled and tossed around in his bed and got up fifty times that night. He said absolutely nothing when Madame Pasteur tried to encourage him and told him, "Now now everything will come out all right"; he sulked in and out of the laboratory; there is no record of it, but without a doubt he prayed. . . .

Pasteur did not fancy going up in balloons and he would not fight duels—but no one can question his absolute gameness when he let the horse doctors get him into this dangerous test.

The crowd that came to judge Pasteur on the famous second day of June, 1881, made the previous ones look like mere assemblages at country baseball games. General Councilors were here to-day as well as senators; magnificoes turned out to see this show—tremendous dignitaries who only exhibited themselves to the public at the weddings and funerals of kings and princes. And the newspaper reporters clustered around the famous de Blowitz.

At two o'clock Pasteur and his cohorts marched upon the field and this time there were no snickers, but only a mighty bellowing of hurrahs. Not one of the twenty-four vaccinated sheep—though two days before millions of deadly germs had taken residence under their hides—not one of these sheep, I say, had so much as a trace of fever. They ate and frisked about as if they had never been within a thousand miles of an anthrax bacillus.

But the unprotected, the not vaccinated beasts—alas—there they lay in a tragic row, twenty-two out of twenty-four of them; and the remaining two were staggering about, at grips with that last inexorable, always victorious enemy of all living things. Ominous black blood oozed from their mouths and noses.

"See! There goes another one of those sheep that Pasteur did not vaccinate!" shouted an awed horse doctor.

V

The Bible does not go into details about what the great wedding crowd thought of Jesus when he turned water into wine, but Pasteur, that second of June, was the impresario of a modern miracle as amazing as any of the marvels wrought by the Man of Galilee, and that day Pasteur's whole audience—who many of them had been snickering skeptics—bowed down before this excitable little half-paralyzed man who could so perfectly protect living creatures from the deadly stings of sub-visible invaders. To me this beautiful experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort is an utterly strange event in the history of man's fight against relentless nature. There is no record of Prometheus bringing the precious fire to mankind amid applause; Galileo was actually clapped in prison for those searchings that have done more than any other to transform the world. We do not even know the names of those completely anonymous genuises who first built the wheel and invented sails and thought to tame a horse.

VI

But here stood Louis Pasteur, while his twenty-four immune sheep scampered about among the carcasses of the same number of pitiful dead ones, here stood this man, I say, in a gruesomely gorgeous stage-setting of an immortal drama, and all the world was there to see and to record and to be converted to his own faith in his passionate fight against needless death.

Now the experiment turned into the likeness of a revival. Doctor Biot, a healer in horses who had been one of the most sarcastic of the Pasteur-baiters, rushed up to him as the last of the not-vaccinated sheep was dying, and cried: "Inoculate me with your vaccines, Mr. Pasteur—just as you have done to those sheep you have saved so wonderfully Then I will submit to the injection of the murderous virus! All men must be convinced of this marvelous discovery!"

"It is true," said another humbled enemy, "that I have made jokes about microbes, but I am a repentant sinner!"

"Well, allow me to remind you of the words of the Gospel," Pasteur answered him. "Joy shall be in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons that need no repentance."

The great de Blowitz cheered and rushed off to file his telegram to the London Times and to the newspapers of the world: "The experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort is a perfect, an unprecedented success."

The world received this news and waited, confusedly believing that Pasteur was a kind of Messiah who was going to lift from men the burden of all suffering. France went wild and called him her greatest son and conferred on him the Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honor. Agricultural societies, horse doctors, poor farmers whose fields were cursed with the poisonous virus of anthrax—all these sent telegrams begging him for thousands of doses of the life-saving vaccine. And Pasteur, with Roux and Chamberland and Thuillier, responded to them with a magnificent disregard of their own health—and of science. For Pasteur, poet that he was, had more faith than the wildest of his new converts in this experiment.

In answer to these telegrams Pasteur turned the little laboratory in the Rue d'Ulm into a vaccine factory—huge kettles bubbled and simmered with the broth in which the tame, the life-saving, anthrax bacilli were to grow. Delicately—but so frantically that it was not quite delicate enough—Roux and Chamberland worked at weakening the murderous bacilli just enough to make the sheep of France a little sick, but not too sick from anthrax. Then all of them sweat at pouring numerous gallons of this bacillus-swarming soup which was the vaccine, into little bottles, a few ounces to each bottle, into clean bottles that had to be absolutely free from all other germs. And they had to do this subtle job without any proper apparatus whatever. I marvel that Pasteur ever attempted it; surely there never has been such blind confidence raised by one clear—but Lord! it might be simply a lucky—experiment.

In moments snatched from this making of vaccine Roux and Chamberland and Thuillier scurried up and down the land of France, and even to Hungary. They inoculated two hundred sheep in this place and five hundred and seventy-six in that—in less than a year hundreds of thousands of beasts had got this life-saving stuff. These wandering vaccinators would drag themselves back into the laboratory from their hard trips, they would get back to Paris probably wanting to get a few drinks or spend an evening with a pretty girl or loaf over a pipe—but Pasteur could not stand the smell of tobacco smoke, and as for wine and women, were not the sheep of France literally baa-ing to be saved? So these young men who were slaves of this battler whose one insane thought was "find-the-microbe-kill-the-microbe"—these faithful fellows took off their coats and peered at anthrax bacilli through the microscopes until their eye rims got red and their eyelashes fell out. In the middle of this work—with the farmers of France yelling for more vaccine—they began to have strange troubles: contaminating germs that had no business there began to pop up among the anthrax bacilli; all at once a weak vaccine that should have just killed a mouse began to knock off large rabbits. . . . Then, just as the scientific desperadoes got these messes straightened out, Pasteur would come in, nagging at them, fuming, fussing because they took so long at their experiments.

He wanted to try to find the deadly virus of hydrophobia. And now at night the chittering of the guinea-pigs and the scurrying fights of the buck-rabbits in their cages were drowned by the eerie noise of mad dogs howling—sinister howls that kept Roux and Chamberland and Thuillier from sleep. . . . What would Pasteur ever have done—he surely would never have got far in his fight with the messengers of death—without those fellows Roux and Chamberland and Thuillier?

Gradually, it was hardly a year after the miracle of Pouilly-le-Fort, it began to be evident that Pasteur, though a most original microbe hunter, was not an infallible God. Disturbing letters began to pile up on his desk; complaints from Montpothier and a dozen towns of France, and from Packisch and Kapuvar in Hungary. Sheep were dying from anthrax—not natural anthrax they had picked up in dangerous fields, but anthrax they had got from those vaccines that were meant to save them! From other places came sinister stories of how the vaccine had failed to work—the vaccine had been paid for, whole flocks of sheep had been injected, the farmers had gone to bed breathing Thank-God-For-Our-Great-Man-Pasteur, only to wake up in the morning to find their fields littered with the carcasses of dead sheep, and these sheep—which ought to have been immune—had died from the lurking anthrax spores that lay in their fields. . . .

Pasteur began to hate to open his letters; he wanted to stop his ears against snickers that sounded from around corners, and then—the worst thing that could possibly happen—came a cold terribly exact scientific report from the laboratory of that nasty little German Koch in Berlin, and this report ripped the practicalness of the anthrax vaccine to tatters. Pasteur knew that Koch was the most accurate microbe hunter in the world.

There is no doubt that Pasteur lost some sleep from this aftermath of his glorious discovery, but, God rest him, he was a gallant man. It was not in him to admit, either to the public or to himself, that his sweeping claims were wrong.

"Have not I said that my vaccines made sheep a little sick with anthrax, but never killed them, and protected them perfectly? Well, I must stick to that," you can hear him mutter between his teeth.

What a searcher this Pasteur was, and yet how little of that fine selfless candor of Socrates or Rabelais is to be found in him. But he is not in any way to be blamed for that, for those two last were only, in their way, looking for truth, while Pasteur's work carried him more and more into the frantic business of saving lives, and in this matter truth is not of the first importance. . . .

In 1882, while his desk was loaded with reports of disasters, Pasteur went to Geneva, and there before the cream of disease-fighters of the world he gave a thrilling speech, subject: "How to guard living creatures from virulent maladies by injecting them with weakened microbes." Pasteur assured them that: "The general principles have been found and one cannot refuse to believe that the future is rich with the greatest hopes."

"We are all animated with a superior passion, the passion for progress and for truth!" he shouted—but unhappily he said no word about those numerous occasions when his vaccine had killed sheep instead of protecting them.

At this meeting Robert Koch sat blinking at Pasteur behind his gold-rimmed spectacles and smiling under his weedy beard at such an unscientific inspirational address. Pasteur seemed to feel something hanging over him, and he challenged Koch to argue with him publicly—knowing that Koch was a much better microbe hunter than an argufier. "I will content myself with replying to Mr. Pasteur's address in a written paper, in the near future," said Koch—who coughed, and sat down.

In a little while this reply appeared. It was dreadful. In this serio-comic answer Dr. Koch began by remarking that he had obtained some of this precious so-called anthrax vaccine from the agent of Mr. Pasteur.

Did Mr. Pasteur say that his first vaccine would kill mice, but not guinea-pigs? Dr. Koch had tested it, and it wouldn’t even kill mice. But some queer samples of it killed sheep!

Did Mr. Pasteur maintain that his second vaccine killed guinea-pigs but not rabbits? Dr. Koch had carefully tested this one too, and found that it often killed rabbits very promptly—and sometimes sheep, poor beasts! which Mr. Pasteur claimed it would guard from death.

Did Mr. Pasteur really believe that his vaccines were really pure cultivations containing nothing but anthrax microbes? Dr. Koch had studied them carefully and found them to be veritable menageries of hideous scum-forming bacilli and strange cocci and other foreign creatures that had no business there.

Finally, was Mr. Pasteur really burning so with a passion for truth? Then why hadn't he told of the bad results as well as the good ones, that had followed the wholesale use of his vaccine?

"Such goings-on are perhaps suitable for the advertising of a business house, but science should reject them vigorously," finished Koch, drily, devastatingly.

Then Pasteur went through the roof and answered Koch’s cool facts in an amazing paper with arguments that would not have fooled the jury of a country debating society. Did Koch dare to make believe that Pasteur’s vaccines were full of contaminating microbes? "For twenty years before Koch's scientific birth in 1876, it has been my one occupation to isolate and grow microbes in a pure state, and therefore Koch’s insinuation that I do not know how to make pure cultivations cannot be taken seriously!" shouted Pasteur.

The French nation, even the great men of the nation, patriotically refused to believe that Koch had demoted their hero from the rank of God of Science—what could you expect from a German anyway?—and they promptly elected Pasteur to the Académie Française, the ultimate honor to bestow on a Frenchman. And on the day of Pasteur's admission this fiery yes-man was welcomed to his place among the Immortal Forty by the skeptical genius, Ernest Renan, the author who had changed Jesus from a God into a good human being, a man who could forgive everything because he understood everything. Renan knew that even if Pasteur sometimes did suppress the truth, he was still sufficiently marvelous. Renan was not a scientist but he was wise enough to know that Pasteur had done a wonderful thing when he showed that weak bugs may protect living beings against virulent ones—even if they would not do it one hundred times out of one hundred.

Regard these two fantastically opposite men facing each other on this solemn day. Pasteur the go-getter, an energetic fighter full of a mixture of faiths that interfered, sometimes, with ultimate—and maybe ugly—truth. And talking to him loftily sits the untroubled Renan with the massiveness of Mount Everest, such a dreadful skeptic that he probably was never quite convinced that he was himself alive, so firmly doubting the value of doing anything that he had become one of the fattest men in France.

Renan called Pasteur a genius and compared him to some of the greatest men that ever lived and then gave the excited, paralyzed, gray-haired, microbe hunter this mild admonition:

"Truth, Sir, is a great coquette; she will not be sought with too much passion, but often is most amenable to indifference. She escapes when apparently caught, but gives herself up if patiently waited for; revealing herself after farewells have been said, but inexorable when loved with too much fervor."

Surely Renan was too wise to think that his lovely words would ever change Pasteur one jot from the headlong untruthful hunter after truth that he was. But just the same, these words sum up the fundamental sadness of Pasteur’s life, they tell of the crown of thorns that madmen wear whose dream it is to change a world in the little seventy years they are allowed to live.

VII

And now Pasteur began—God knows why—to stick little hollow glass tubes into the gaping mouths of dogs writhing mad with rabies. While two servants pried apart and held open the jowls of a powerful bulldog, Pasteur stuck his beard within a couple of inches of those fangs whose snap meant the worst of deaths, and, sprinkled sometimes with a maybe fatal spray, he sucked up the froth into his tube—to get a specimen in which to hunt for the microbe of hydrophobia. I wish to forget, now, everything that I have said about his showmanship, his unsearcherlike go-gettings. This business of his gray eyes looking that bulldog in the mouth—this was no grandstand stuff.

Why did Pasteur set out to trap the germ of rabies? That is a mystery, because there were a dozen other serious diseases, just then, whose microbes had not yet been found, diseases that killed many more people than rabies had ever put to death, diseases that were not nearly so surely deadly to an adventurous experimenter as rabies would be—if one of those dogs should get loose. . . .

It must have been the artist, the poet in him that urged him on to this most hard and dangerous hunting, for Pasteur himself said: "I have always been haunted by the cries of those victims of the mad wolf that came down the street of Arbois when I was a little boy. . . ." Pasteur knew the way the yells of a mad dog curdle the blood of every one. He remembered that less than a hundred years before in France, laws had to be passed against the poisoning, the strangling, the shooting of wretched people whom frightened fellow-townsmen just suspected of having rabies. Doubtless he saw himself the deliverer of men from such crazy fear—such hopeless suffering.

And then, in this most magnificent and truest of all his searchings, Pasteur started out, as he so often did, by making mistakes. In the saliva of a little child dying from hydrophobia he discovered a strange motionless germ that he gave the unscientific name of "microbe-like-an-eight." He read papers at the Academy that hinted about this figure-eight germ having something to do with the mysterious cause of hydrophobia. But in a little while this trail proved to be a blind one, for with Roux and Chamberland he found—after he had settled down and got his teeth into this search—that this eight-microbe could be found in the mouths of many healthy people who had never been anywhere near a mad dog.

Presently, late in 1882, he ran on to his first clew. "Mad dogs are scarce just now, old Bourrel the veterinarian brings me very few of them, and people with hydrophobia are still harder to get hold of—we've got to produce this rabies in animals in our laboratory and keep it going there—otherwise we won't be able to go on studying it steadily," he pondered.

He was more than sixty, and he was tired.

Then one day, a lassoed mad dog was brought into the laboratory; dangerously he was slid into a big cage with healthy dogs and allowed to bite them. Roux and Chamberland fished froth out of the mouth of this mad beast and sucked it up into syringes and injected this stuff into rabbits and guinea-pigs. Then they waited eagerly to see this menagerie develop the first signs of madness. Sometimes—alas—the experiment worked, but other very irritating times it did not; four healthy dogs had been bitten and six weeks later they came in one morning to find two of these creatures lashing about their cages, howling—but for months after that the other two showed no sign of rabies; there was no rime or reason to this business, no regularity, confound it! this was not science! And it was the same with the guinea-pigs and rabbits: two of the rabbits might drag out their hind legs with a paralysis—then die in dreadful convulsions, but the other four would go on chewing their greens as if there were no mad-dog virus within a million miles of them.

Then one day a little idea came to Pasteur, and he hurried to tell it to Roux.

"This rabies virus that gets into people by bites, it settles in their brains and spinal cords. . . . All the symptoms of hydrophobia show that it's the nervous system that this virus—this bug we can't find—attacks. . . .

"That's where we have to look for the unknown microbe . . . that's where we can grow it maybe, even without seeing it . . . maybe we could use the living animal's brain instead of a bottle of soup . . . a funny culture-bottle that would be, but. . . .

"When we inject it under the skin—the virus may get lost in the body before it can travel to the brain—if I could only stick it right into a dog's brain . . . !"

Roux listened to these dreamings of Pasteur, he listened bright-eyed to these fantastic imaginings. . . . Another man than Roux might have thought Pasteur completely crazy. . . . The brain of a dog or rabbit instead of a bottle of broth, indeed! What nonsense! But not to Roux!

"But why not put the virus right into a dog's brain, master, I can trephine a dog—I can drill a little hole in his skull—without hurting him—without damaging his brain at all . . . it would be easy . . ." said Roux.

Pasteur shut Roux up, furiously. He was no doctor, and he did not know that surgeons can do this operation on human beings even, quite safely. "What! bore a hole right through a dog's skull—why, you'd hurt the poor beast terribly . . . you would damage his brain . . . you would paralyze him . . . No! I will not permit it!"

So near was Pasteur, by reason of his tender-heartedness, so close was he to failing completely in winning to the most marvelous of his gifts to men. He quailed before the stern experiment that his weird idea demanded. But Roux—the faithful, the now almost forgotten Roux—saved him by disobeying him.

For, a few days later when Pasteur left the laboratory to go to some meeting or other, Roux took a healthy dog, put him easily out of pain with a little chloroform, and bored a hole in the beast's head and exposed his palpitating, living brain. Then up into a syringe he drew a little bit of the ground-up brain of a dog just dead with rabies: "This stuff must be swarming with those rabies microbes that are maybe too small for us to see," he pondered; and through the hole in the sleeping dog's skull went the needle of the syringe, and into the living brain Roux slowly, gently shot the deadly rabid stuff. . . .

Next morning Roux told Pasteur about it— "What!" shouted Pasteur. "Where is the poor creature . . . he must be dying . . . paralyzed. . . ."

But Roux was already down the stairs, and in an instant he was back, his operated dog prancing in ahead of him, jumping gayly against Pasteur, sniffing 'round among the old broth bottles under the laboratory benches. Then Pasteur realized Roux's cleverness—and the new road of experiment that lay before him, and though he was not fond of dogs, his joy made him fuss over this one: "Good dog, excellent beast!" Pasteur said, and dreamed: "This beast will show that my idea will work. . . ."

Sure enough, less than two weeks later the good creature began to howl mournful cries and tear up his bed and gnaw at his cage—and in a few days more he was dead, and this brute died, as you will see, so that thousands of mankind might live.

Now Pasteur and Roux and Chamberland had a sure way, that worked one hundred times out of one hundred, of giving rabies to their dogs and guinea-pigs and rabbits. "We cannot find the microbe—surely it must be too tiny for the strongest microscope to show us—there's no way to grow it in flasks of soup . . . but we can keep it alive—this deadly virus—in the brains of rabbits . . . that is the only way to grow it," you can hear Pasteur telling Roux and Chamberland.

Never was there a more fantastic experiment in all of microbe hunting, or in any science, for that matter; never was there a more unscientific feat of science than this struggling, by Pasteur and his boys, with a microbe they couldn't see—a weird bug of whose existence they only knew by its invisible growth in the living brains and spinal cords of an endless succession of rabbits and guinea-pigs and dogs. Their only knowledge that there was such a thing as the microbe of rabies was the convulsive death of the rabbits they injected, and the fearful cries of their trephined dogs. . . .

Then Pasteur and his assistants started on their outlandish—any wise man would say their impossible—adventure of taming this vicious virus that they could not see. There were little interruptions; Roux went with Thuillier to fight the cholera in Egypt and there, you will remember, Thuillier died; and Pasteur went out into the rural pig-sties of France to discover the microbe and find a vaccine against a disease that was just then murdering French swine. But Pasteur stopped getting entangled in those vulgar arguments which were so often to his discredit, and the three of them locked themselves in their laboratory in the Rue d’Ulm with their poor paralyzed and dangerous animals. They sweat through endless experiments.

Pasteur mounted guard over his young men and kept their backs bent over their benches as if they were some higher kind of galley slave. He watched their perilous experiments with one eye and kept the other on the glass door of the workroom, and when he saw some of Roux's and Chamberland's friends approaching, to ask them maybe to come out for a glass of beer on the terrace of a near-by café, the master would hurry out and tell the interlopers: "No. No! Not now! Cannot you see? They are busy—it is a most important experiment they are doing!"

Months—gray months went by during which it seemed to all of them that there was no possible way of weakening the invisible virus of rabies. . . . One hundred animals, alas, out of every hundred that they injected—died. You would think that Roux and Chamberland, still youngsters, would have been the indomitable ones, the never-say-die men of this desperate crew. But on the contrary!

"It's no go, master," said they, making limp waves of their hands toward the cages with their paralyzed beasts—toward the tangled jungles of useless tubes and bottles. . . .

Then Pasteur's eyebrows cocked at them, and his thinning gray hair seemed to stiffen: "Do the same experiment over again—no matter if it failed last time—it may look foolish to you, but the important thing is not to leave the subject!" Pasteur shouted, in a fury. So it was that this man scolded his monkish disciples and prodded them to do useless tests over and over and over—with no reasons, with complete lack of logic. With every fact against him Pasteur searched and tried and failed and tried again with that insane neglect of common sense that sometimes turns hopeless causes into victories.

Indeed, why wasn't this setting out to tame the hydrophobia virus—why wasn't it a nonsensical wild-goose chase? There was in all human history no single record of any man or beast getting better from this horrible malady, once the symptoms had declared themselves, once the mysterious messengers of evil had wormed their unseen way into the spinal cord and brain. It was this kind of murderous stuff that Pasteur and his men balanced on the tips of their knives, sucked up into their glass pipettes within an inch from the lips—stuff that was separated from their mouths by a thin little wisp of cotton. . . .

Then, one exciting day, the first sweet music of encouragement came to these gropers in the dark—one of their dogs inoculated with the surely fatal stuff from a rabid rabbit's brain —this dog came down with his weird barkings and portentous shiverings and slatherings—and then miraculously got completely better! Excitedly, a few weeks later, they shot this first of all recovered beasts with a deadly virus, directly into his brain they injected the wee murderers. The little wound on his head healed quickly—anxiously Pasteur waited for his doomful symptoms to come on him, but these signs never came. For months the dog romped about his cage. He was absolutely immune!

"Now we know it—we know we have a chance. . . . When a beast once has rabies and gets better from it, there will be no recurrence. . . . We must find a way to tame the virus now," said Pasteur to his men, who agreed, but were perfectly certain that there was no way to tame that virus.

But Pasteur began inventing experiments that no god would have attempted; his desk was strewn with hieroglyphic scrawls of them. And at eleven in the morning, when the records of the results of the day before had been carefully put down, he would call Roux and Chamberland, and to them he would read off some wild plan for groping after this unseen unreachable virus—some fantastic plan for getting his fingers on it inside the body of a rabbit—to weaken it.

"Try this experiment to-day!" Pasteur would tell them.

"But that is technically impossible!" they protested.

"No matter—plan it any way you wish, provided you do it well," Pasteur replied. (He was, those days, like old Ludwig van Beethoven writing unplayable horn parts for his symphonies—and then miraculously discovering hornblowers to play those parts.) For, one way or another, the ingenious Roux and Chamberland devised tricks to do those crazy experiments. . . .

And at last they found a way of weakening the savage hydrophobia virus—by taking out a little section of the spinal cord of a rabbit dead of rabies, and hanging this bit of deadly stuff up to dry in a germ-proof bottle for fourteen days. This shriveled bit of nervous tissue that had once been so deadly they shot into the brains of healthy dogs—and those dogs did not dies. . . .

"The virus is dead—or better still very much weakened," said Pasteur, jumping at the latter conclusion with no sense or reason. "Now we'll try drying other pieces of virulent stuff for twelve days—ten days—eight days—six days, and see if we can't just give our dogs a little rabies . . . then they ought to be immune. . . ."

Savagely they fell to this long will o' the wisp of an experiment. For fourteen days Pasteur walked up and down the bottle and microscope and cage-strewn unearthly workshop and grumbled and fretted and made scrawls in that everlasting notebook of his. The first day the dogs were dosed with the weakened—the almost extinct virus that had been dried for fourteen days; the second day they received a shot of the slightly stronger nerve stuff that had been thirteen days in its bottle; and so on until the fourteenth day—when each beast was injected with one-day-dried virus that would have surely killed a not-inoculated animal.

For weeks they waited—hair graying again—for signs of rabies in these animals, but none ever came. They were happy, these ghoulish fighters of death! Their clumsy terrible fourteen vaccinations had not hurt the dogs—but were they immune?

Pasteur dreaded it—if this failed all of these years of work had gone for nothing, and "I am getting old, old . . ." you can hear him whispering to himself. But the test had to be made. Would the dogs stand an injection of the most deadly rabid virus—right into their brains—a business that killed an ordinary dog one hundred times out of one hundred?

Then one day Roux bored little holes through the skulls of two vaccinated dogs—and two not vaccinated ones: and into all four went a heavy dose of the most virulent virus. . . .

One month later, Pasteur and his men, at the end of three years of work, knew that victory over hydrophobia was in their hands. For, while the two vaccinated dogs romped and sniffed about their cages with never a sign of anything ailing them the two that had not received the fourteen protective doses of dried rabbit's brain—these two had howled their last howls and died of rabies.

Now immediately—the life-saver in this man was always downing the mere searcher—Pasteur's head buzzed with plans to wipe hydrophobia from the earth, he had a hundred foolish projects, and he walked in a brown world of thought, in a mist of plans that Roux and Chamberland, and not even Madame Pasteur could penetrate. It was 1884, and when Pasteur forgot their wedding anniversary, the long-suffering lady wrote to her daughter:

"Your father is absorbed in his thoughts, talks little, sleeps little, rises at dawn, and, in one word, continues the life I began with him this day thirty-five years ago."

At first Pasteur thought of shooting his weakened rabies virus into all the dogs of France in one stupendous Napoleonic series of injections: "We must remember that no human being is ever attacked with rabies except after being bitten by a rabid dog. . . . Now if we wipe it out of dogs with our vaccine . . ." he suggested to the famous veterinarian, Nocard, who laughed, and shook his head.

"There are more than a hundred thousand dogs and hounds and puppies in the city of Paris alone," Nocard told him, "and more than two million, five hundred thousand dogs in all of France—and if each of these brutes had to get fourteen shots of your vaccine fourteen days in a row . . . where would you get the men? Where would you get the time? Where the devil would you get the rabbits? Where would you get sick spinal cord enough to make one-thousandth enough vaccine?"

Then finally there dawned on Pasteur a simple way out of his trouble: "It's not the dogs we must give our fourteen doses of vaccine," he pondered, "it's the human beings that have been bitten by mad dogs. . . ."

"How easy! . . . After a person has been bitten by a mad dog, it is always weeks before the disease develops in him. . . . The virus has to crawl all the way from the bite to the brain. . . . While that is going on we can shoot in our fourteen doses . . . and protect him!" and hurriedly Pasteur called Roux and Chamberland together, to try it on the dogs first.

They put mad dogs in cages with healthy ones, and the mad dogs bit the normal ones.

Roux injected virulent stuff from rabid rabbits into the brains of other healthy dogs.

Then they gave these beasts, certain to die if they were left alone—they shot the fourteen stronger and stronger doses of vaccine into them. It was an unheard-of triumph! For every one of these creatures lived—threw off perfectly, mysteriously, the attacks of their unseen assassins, and Pasteur—who had had a bitter experience with his anthrax inoculations—asked that all of his experiments be checked by a commission of the best medical men of France, and at the end of these severe experiments the commission announced:

"Once a dog is made immune with the gradually more virulent spinal cords of rabbits dead of rabies, nothing on earth can give him the disease."

From all over the world came letters, urgent telegrams, from physicians, from poor fathers and mothers who were waiting terror-smitten for their children, mangled by mad dogs, to die—frantic messages poured in on Pasteur, begging him to send them his vaccine to use on threatened humans. Even the magnificent Emperor of Brazil condescended to write Pasteur, begging him . . .

And you may guess how Pasteur was worried! This was no affair like anthrax, where, if the vaccine was a little, just a shade too strong, a few sheep would die. Here a slip meant the lives of babies. . . . Never was any microbe hunter faced with a worse riddle. "Not a single one of all my dogs has ever died from the vaccine," Pasteur pondered. "All of the bitten ones have been perfectly protected by it. . . . It must work the same way on humans—it must . . . but . . ."

And then sleep once more was not to be had by this poor searcher who had made a too wonderful discovery. . . . Horrid pictures of babies crying for the water their strangled throats would not let them drink—children killed by his own hands—such visions floated before him in the dark. . . .

For a moment the actor, the maker of grand theatric gestures, rose in him again: "I am much inclined to begin on myself—inoculating myself with rabies, and then arresting the consequences; for I am beginning to feel very sure of my results," he wrote to his old friend, Jules Verçel.

At last, mercifully, the worried Mrs. Meister from Meissengott in Alsace took the dreadful decision out of Pasteur's unsure hands. This woman came crying into the laboratory, leading her nine-year-old boy, Joseph, gashed in fourteen places two days before by a mad dog. He was a pitifully whimpering, scared boy—hardly able to walk.

"Save my little boy—Mr. Pasteur," this woman begged him.

Pasteur told the woman to come back at five in the evening, and meanwhile he went to see the two physicians, Vulpian and Grancher—admirers who had been in his laboratory, who had seen the perfect way in which Pasteur could guard dogs from rabies after they had been terribly bitten. That evening they went with him to see the boy, and when Vulpian saw the angry festering wounds he urged Pasteur to start his inoculations: "Go ahead," said Vulpian, "if you do nothing it is almost sure that he will die."

And that night of July 6, 1885, they made the first injection of the weakened microbes of hydrophobia into a human being. Then, day after day, the boy Meister went without a hitch through his fourteen injections—which were only slight pricks of the hypodermic needle into his skin.

And the boy went home to Alsace and had never a sign of that dreadful disease.

Then all fears left Pasteur—it was very much like the case of that first dog that Roux had injected years before, against the master's wishes. So it was now with human beings; once little Meister came through unhurt, Pasteur shouted to the world that he was prepared to guard the people of the world from hydrophobia. This one case had completely chased his fears, his doubts—those vivid but not very deep-lying doubts of the artist that was in Louis Pasteur.

The tortured bitten people of the world began to pour into the laboratory of the miracle-man of the Rue d’Ulm. Research for a moment came to an end in the messy small suite of rooms, while Pasteur and Roux and Chamberland sorted out polyglot crowds of mangled ones, babbling in a score of tongues: "Pasteur—save us!"

And this man who was no physician—who used to say with proud irony: "I am only a chemist,"—this man of science who all his life had wrangled bitterly with doctors, answered these cries and saved them. He shot his complicated, illogical fourteen doses of partly weakened germs of rabies—unknown microbes of rabies—into them and sent these people healthy back to the four corners of the earth.

From Smolensk in Russia came nineteen peasants, moujiks who had been set upon by a mad wolf nineteen days before, and five of them were so terribly mangled they could not walk at all, and had to be taken to the Hotel Dieu. Strange figures in fur caps they came, saying: "Pasteur—Pasteur," and this was the only word of French they knew.

Then Paris went mad—as only Paris can—with excited concern about these bitten Russians who must surely die—it was so long since they had been attacked—and the town talked of nothing else while Pasteur and his men started their injections. The chances of getting hydrophobia from the bites of mad

wolves are eight out of ten: out of these nineteen Russians, fifteen were sure to die. . . .

"Maybe," said every one, "they will all die—it is more than two weeks since they were attacked, poor fellows; the malady must have a terrible start, they have no chance. . . ." Such was the gabble of the Boulevards.

Perhaps, indeed, it was too late. Pasteur could not eat nor did he sleep at all. He took a terrible risk, and morning and night, twice as quickly as he had ever made the fourteen injections—twice a day to make up for lost time—he and his men shot the vaccine into the arms of the Russians.

And at last a great shout of pride went up for this man Pasteur, went up from the Parisians, and all of France and all the world raised a pæan of thanks to him—for the vaccine marvelously saved all but three of the doomed peasants. The moujiks returned to Russia and were welcomed with the kind of awe that greets the return of hopeless sick ones who have been healed at some miraculous shrine. And the Tsar of All the Russias sent Pasteur the diamond cross of Ste. Anne, and a hundred thousand francs to start the building of that house of microbe hunters in the Rue Dutot in Paris—that laboratory now called the Institut Pasteur. From all over the world—it was the kind of burst of generosity that only great disasters usually call out—from every country in the earth came money, piling up into millions of francs for the building of a laboratory in which Pasteur might have everything needed to track down other deadly microbes, to invent weapons against them. . . .

The laboratory was built, but Pasteur's own work was done; his triumph was too much for him; it was a kind of trigger, perhaps, that snapped the strain of forty years of never before heard-of ceaseless searching. He died in 1895 in a little house near the kennels where they now kept his rabid dogs, at Villeneuve l'Etang, just outside of Paris. His end was that of the devout Catholic, the mystic he had always been. In one hand he held a crucifix and in the other lay the hand of the most patient, obscure and important of his collaborators—Madame Pasteur. Around him, too, were Roux and Chamberland and those other searchers he had worn to tatters with his restless energy, those faithful ones he had abused, whom he had above all inspired; and these men who had risked their lives in the carrying out of his wild forays against death would now have died to save him, if they could.

That was the perfect end of this so human, so passionately imperfect hunter of microbes and saver of lives.

But there is another end of his career that I like to think of more—and that was the day, in 1892, of Pasteur's seventieth birthday—when a medal was given to him at a great meeting held to honor him, at the Sorbonne in Paris. Lister was there, and many other famous men from other nations, and in tier upon tier, above these magnificoes who sat in the seats of honor, were the young men of France—the students of the Sorbonne and the colleges and the high schools. There was a great buzz of young voices—all at once a hush, as Pasteur limped up the aisle, leaning on the arm of the President of the French Republic. And then—it is the kind of business that is usually pulled off to welcome generals and that kind of hero who has directed the futile butchering of thousands of enemies—the band of the Republican Guard blared out into a triumphal march.

Lister, the prince of surgeons, rose from his seat and hugged Pasteur and the gray-bearded important men and the boys in the top galleries cried and shook the walls with the roar of their cheering. At last the old microbe hunter gave his speech—the voice of the fierce arguments was gone and his son had to speak it for him—and his last words were a hymn of hope, not so much for the saving of life as a kind of religious cry for a new way of life for men. It was to the students, to the boys of the high schools he was calling:

". . . Do not let yourselves be tainted by a deprecating and barren skepticism, do not let yourselves be discouraged by the sadness of certain hours which pass over nations. Live in the serene peace of laboratories and libraries. Say to yourselves first: What have I done for my instruction? and, as you gradually advance, What have I done for my country? until the time comes when you may have the immense happiness of thinking that you have contributed in some way to the progress and good of humanity. . . ."