Microbe Hunters/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV

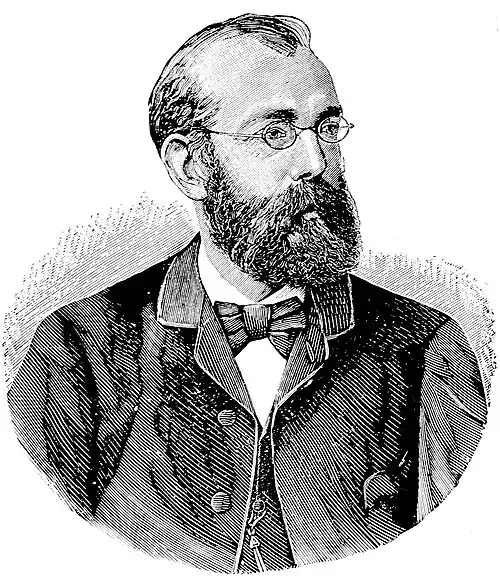

KOCH

THE DEATH FIGHTER

I

In those astounding and exciting years between 1860 and 1870, when Pasteur was saving vinegar industries and astonishing emperors and finding out what ailed sick silkworms, a small, serious, and nearsighted German was learning to be a doctor at the University of Gottingen. His name was Robert Koch. He was a good student, but while he hacked at cadavers he dreamed of going tiger-hunting in the jungle. Conscientiously he memorized the names of several hundred bones and muscles, but the fancied moan of the whistles of steamers bound for the East chased this Greek and Latin jargon out of his head.

Koch wanted to be an explorer; or to be a military surgeon and win Iron Crosses; or to be ship’s doctor and voyage to impossible places. But alas, when he graduated from the medical college in 1866 he became an interne in a not very interesting insane asylum in Hamburg. Here, busy with raving maniacs and helpless idiots, the echoes of Pasteur’s prophecies that there were such things as terrible man-killing microbes hardly reached Koch’s ears. He was still listening for steamerwhistles and in the evenings he took walks down by the wharves with Emmy Fraatz; he begged her to marry him; he held out the bait of romantic trips around the world to her. Emmy told Robert that she would marry him, but on condition that he forget this nonsense about an adventurous life, provided that he would settle down to be a practicing doctor, a good useful citizen, in Germany.

Koch listened to Emmy—for a moment the allure of fifty years of bliss with her chased away his dreams of elephants and Patagonia—and he settled down to practice medicine; he began what was to him a totally uninteresting practice of medicine in a succession of unromantic Prussian villages.

Just now, while Koch wrote prescriptions and rode horseback through the mud and waited up nights for Prussian farmer women to have their babies, Lister in Scotland was beginning to save the lives of women in childbirth—by keeping microbes away from them. The professors and the students of the medical colleges of Europe were beginning to be excited and to quarrel about Pasteur’s theory of malignant microbes, here and there men were trying crude experiments, but Koch was almost as completely cut off from this world of science as old Leeuwenhoek had been, two hundred years before, when he first fumbled at grinding glass into lenses in Delft in Holland. It looked as if his fate was to be the consoling of sick people and the beneficent and praiseworthy attempt to save the lives of dying people—mostly, of course, he did not save them—and his wife Emmy was quite satisfied with this and was proud when Koch earned five dollars and forty-five cents on especially busy days.

But Robert Koch was restless. He trekked from one deadly village to another still more uninteresting, until at last he came to Wollstein, in East Prussia, and here, on his twenty-eighth birthday, Mrs. Koch bought him a microscope to play with.

You can hear the good woman say: “Maybe that will take Robert’s mind off what he calls his stupid practice. . . perhaps this will satisfy him a little. . . he’s always looking at everything with his old magnifying glass. . . .”

Alas for her, this new microscope, this plaything, took her husband on more curious adventures than any he would have met in Tahiti or Lahore; and these weird experiences—that Pasteur had dreamed of but which no man had ever had before—came on him out of the dead carcasses of sheep and cows. These new sights and adventures jumped at him impossibly on his very doorstep, and in his own drug-reeking office that he was so tired of, that he was beginning to loathe.

"I hate this bluff that my medical practice is . . . it isn't because I do not want to save babies from diphtheria . . . but mothers come to me crying—asking me to save their babies—and what can I do?—Grope . . . fumble . . . reassure them when I know there is no hope. . . . How can I cure diphtheria when I do not even know what causes it, when the wisest doctor in Germany doesn't know? . . ." So you can imagine Koch complaining bitterly to Emmy, who was irritated and puzzled, and thought that it was a young doctor's business to do as well as he could with the great deal of knowledge that he had got at the medical school—oh! would he never be satisfied?

But Koch was right. What, indeed, did doctors know about the mysterious causes of disease? Pasteur's experiments were brilliant, but they had proved nothing about the how and why of human sicknesses. Pasteur was a trail-blazer, a fore-runner crying possible future great victories over disease, shouting about magnificent stampings out of epidemics; but meanwhile the moujiks of desolate towns in Russia were still warding off scourges by hitching four widows to a plow and with them drawing a furrow round their villages in the dead of night—and their doctors had no sounder protection to offer them.

"But the professors, the great doctors in Berlin, Robert, they must know what is the cause of these sicknesses you don't know how to stop." So Frau Koch might have tried to console him. But in 1873—that is only fifty years ago—I must repeat that the most eminent doctors had not one bit better explanation for the causes of epidemics than the ignorant Russian villagers who hitched the town widows to their plows. In Paris Pasteur was preaching that microbes would soon be found to be the murderers of consumptives: and against this crazy prophet rose the whole corps of the doctors of Paris, headed by the distinguished brass-buttoned Doctor Pidoux.

"What!" roared this Pidoux, "consumption due to a germ—one definite kind of germ? Nonsense! A fatal thought! Consumption is one and many at the same time. Its conclusion is the necrobiotic and infecting destruction of the plasmatic tissue of an organ by a number of roads that the hygienist and the physician must endeavor to close!" It was so that the doctors fought Pasteur's prophecies with utterly meaningless and often idiotic words.

II

Koch was spending his evenings fussing with his new microscope, he was beginning to find out just the right amount of light to shoot up into its lens with the reflecting mirror, he was learning just how needful it was to have his thin glass slides shining clean—those bits of glass on which he liked to put drops of blood from the carcasses of sheep and cows, that had died of anthrax. . . .

Anthrax was a strange disease which was worrying farmers all over Europe, that here and there ruined some prosperous owner of a thousand sheep, that in another place sneaked in and killed the cow—the one support—of a poor widow. There was no rime or reason to the way this plague conducted its maraudings; one day a fat lamb in a flock might be frisking about, that evening this same lamb refused to eat, his head drooped a little—and the next morning the farmer would find him cold and stiff, his blood turned ghastly black. Then the same thing would happen to another lamb, and a sheep, four sheep, six sheep—there was no stopping it. And then the farmer himself, and a shepherd, and a woolsorter, and a dealer in hides might break out in horrible boils—or gasp out their last breaths in a swift pneumonia.

Koch had started using his microscope with the more or less thorough aimlessness of old Leeuwenhoek; he examined everything under the sun, until he ran on to this blood of sheep and cattle dead of anthrax. Then he began to concentrate, to forget about making a call when he found a dead sheep in a field—he haunted butcher shops to find out about the farms where anthrax was killing the flocks. Koch hadn't the leisure of Leeuwenhoek; he had to snatch moments for his peerings, between prescribing for some child that bawled with a bellyache and the pulling out of a villager's aching tooth. In these interrupted hours he put drops of the blackened blood of a cow dead of anthrax between two thin pieces of glass, very clean shining bits of glass. He looked down the tube of his microscope and among the wee round drifting greenish globules of this blood he saw strange things that looked like little sticks. Sometimes these sticks were short, there might be only a few of them, floating, quivering a little, among the blood globules. But here were others, hooked together without joints—many of them ingeniously glued together till they appeared to him like long threads a thousand times thinner than the finest silk.

"What are these things . . . are they microbes . . . are they alive? They do not move . . . maybe the sick blood of these poor beasts just changes into these threads and rods," Koch pondered. Other men of science, Davaine and Rayer in France, had seen these same things in the blood of dead sheep; and they had announced that these rods were bacilli, living germs, that they were undoubtedly the real cause of anthrax—but they hadn't proved it, and except for Pasteur, no one in Europe believed them. But Koch was not particularly interested in what anybody else thought about the threads and rods in the blood of dead sheep and cattle—the doubts and the laughter of doctors failed to disturb him, and the enthusiasms of Pasteur did not for one moment make him jump at conclusions. Luckily nobody anxious to develop young microbe hunters had ever heard of Koch, he was a lone wolf searcher—he was his own man, alone with the mysterious tangled threads in the blood of the dead beasts.

"I do not see a way yet of finding out whether these little sticks and threads are alive," he meditated, "but there are other things to learn about them. . . ." Then, curiously, he stopped studying diseased creatures and began fussing around with perfectly healthy ones. He went down to the slaughter houses and visited the string butchers and hobnobbed with the meat merchants of Wollstein, and got bits of blood from tens, dozens, fifties of healthy beasts that had been slaughtered for meat. He stole a little more time from his tooth-pullings and professional layings-on-of-hands. More and more Mrs. Koch worried at his not tending to his practice. He bent over his microscope, hours on end, watching the drops of healthy blood.

"Those threads and rods are never found in the blood of any healthy animal," Koch pondered, "—this is all very well, but it doesn't tell me whether they are bacilli, whether they are alive . . . it doesn't show me that they grow, breed, multiply. . . ."

But how to find this out? Consumptives—whom, alas, he could not help—babies choking with diphtheria, old ladies who imagined they were sick, all his cares of a good physician began to be shoved away into one corner of his head. How-to-prove-these-wee-sticks-are-alive, this question made him forget to sign his name to prescriptions, it made him a morose husband, it made him call the carpenter in to put up a partition in his doctor's office. And behind this wall Koch stayed more and more hours, with his microscope and drops of black blood of sheep mysteriously dead—and with a growing number of cages full of scampering white mice.

"I haven't the money to buy sheep and cows for my experiments," you can hear him muttering, while some impatient invalid shuffled her feet in the waiting room, "besides, cows would be a little inconvenient to have around my office—but maybe I can give anthrax to these mice . . . maybe in them I can prove that the sticks really grow. . . ."

So this foiled globe-trotter started on his strange explorations. To me Koch is a still more weird and uncanny microbe hunter than Leeuwenhoek, certainly he was just as much of a self-made scientist. Koch was poor, he had his nose on the grindstone of a medical practice, all the science he knew was what a common medical course had taught him—and from this, God knows, he had learned nothing whatever about the art of doing experiments; he had no apparatus but Emmy's birthday present, that beloved microscope—everything else he had to invent and fashion out of bits of wood and strings and sealing wax. Worst of all, when he came into the living room from his mice and microscope to tell Frau Koch about the new strange things he had discovered, this good lady wrinkled up her nose and told him:

"But, Robert, you smell so!"

Then he hit upon a sure way to give mice the fatal disease of anthrax. He hadn't a convenient syringe with which to shoot the poisonous blood into them, but after sundry cursings and the ruin of a number of perfectly good mice, he took slivers of wood, cleaned them carefully, heated them in an oven to kill any chance ordinary microbes that might be sticking to them. These slivers he dipped into drops of blood from sheep dead of anthrax, blood filled with the mysterious, motionless threads and rods, and then—heaven knows how he managed to hold his wiggling mouse—he made a little cut with a clean knife at the root of the tail of the mouse, and into this cut he delicately slid the blood-soaked splinter. He dropped this mouse into a separate cage and washed his hands and went off in a kind of conscientious wool-gathering way to see what was wrong with a sick baby. . . . "Will that beast, that mouse die of anthrax. . . . Your child will be able to go back to school next week, Frau Schmidt. . . . I hope I didn't get any of that anthrax blood into that cut on my finger. . . ." Such was Koch's life.

And next morning Koch came into his home-made laboratory—to find the mouse on its back, stiff, its formerly sleek fur standing on end and its whiteness of yesterday turned into a leaden blue, its legs sticking up in the air. He heated his knives, fastened the poor dead creature onto a board, dissected it, opened it down to its liver and lights, peered into every corner of its carcass. "Yes, this looks like the inside of an anthrax sheep . . . see the spleen, how big, how black it is . . . it almost fills the creature's body. . . ." Swiftly he cut with a clean heated knife into this swollen spleen and put a drop of the blackish ooze from it before his lens. . . .

At last he muttered: "They're here, these sticks and threads . . . they are swarming in the body of this mouse, exactly as they were in the drop of dead sheep's blood that I dipped the little sliver in yesterday." Delighted, Koch knew that he had caused in the mouse, so cheap to buy, so easy to handle, the sickness of sheep and cows and men. Then for a month his life became a monotony of one dead mouse after another, as, day after day, he took a drop of the blood or the spleen of one dead beast, put it carefully on a clean splinter, and slid this sliver into a cut at the root of the tail of a new healthy mouse. Each time, next morning, Koch came into his laboratory to find the new animal had died, of anthrax, and each time in the blood of the dead beast his lens showed him myriads of those sticks and tangled threads—those motionless, twenty-five-thousandth-of-an-inch thick filaments that he could never discover in the blood of any healthy animal.

"These threads must be alive," Koch pondered, "the sliver that I put into the mouse has a drop of blood on it and that drop holds only a few hundreds of those sticks—and these have grown into billions in the short twenty-four hours in which the beast became sick and died. . . . But, confound it, I must see these rods grow—and I can't look inside a live mouse!"

How – shall – I – find – a – way – to – see – the – rods – grow – out – into – threads? This question pounded at him while he counted pulses and looked at his patient’s tongues. In the evenings he hurried through supper and growled good-night to Mrs. Koch and shut himself up in his little room that smelled of mice and disinfectant, and tried to find ways to grow his threads outside a mouse's body. At this time Koch knew little or nothing about the yeast soups and flasks of Pasteur, and the experiments he fussed with had the crude originality of the first cave man trying to make fire.

"I will try to make these threads multiply in something that is as near as possible like the stuff an animal's body is made of—it must be just like living stuff," Koch muttered, and he put a wee pin-point piece of spleen from a dead mouse—spleen that was packed with the tangled threads, into a little drop of the watery liquid from the eye of an ox. "That ought to be good food for them," he grumbled. "But maybe, too, the threads have got to have the temperature of a mouse's body to grow," he said, and he built with his own hands a clumsy incubator, heated by an oil lamp. In this uncertain machine he deposited the two flat pieces of glass between which he had put the drop of liquid from the ox-eye. Then, in the middle of the night, after he had gone to bed, but not to sleep, he got up to turn the wick of his smoky incubator lamp down a little, and instead of going back to rest, again and again he slid the thin strips of glass with their imprisoned infinitely little sticks before his microscope. Sometimes he thought he could see them growing—but he could not be sure, because other microbes, swimming and cavorting ones, had an abominable way of getting in between these strips of glass, over-growing, choking out the slender dangerous rods of anthrax.

"I must grow my rods pure, absolutely pure, without any other microbes around," he muttered. And he kept flounderingly trying ways to do this, and his perplexity pushed up huge wrinkles over the bridge of his nose, and built crow's-feet round his eyes. . . .

Then one day a perfectly easy, a foolishly simple way to watch his rods grow flashed into Koch's head. "I'll put them in a hanging-drop, where no other bugs can get in among them," he muttered. On a flat, clear piece of glass, very thin, which he had heated thoroughly to destroy all chance microbes, Koch placed a drop of the watery fluid of an eye from a just butchered healthy ox; into this drop he delicately inserted the wee-est fragment of spleen, fresh out of a mouse that had a moment before died miserably of anthrax. Over the drop he put a thick oblong piece of glass with a concave well scooped out of it so that the drop would not be touched. Around this well he had smeared some vaseline to make the thin glass stick to the thick one. Then, dextrously, he turned this simple apparatus upside down, and presto!—here was his hanging-drop, his ox-eye fluid with its rod-swarming spleen, imprisoned in the well—away from all other microbes.

Koch did not know it, perhaps, but this—apart from that day when Leeuwenhoek first saw little animals in rain water—was a most important moment in microbe hunting, and in the fight of mankind against death.

"Nothing can get into that drop—only the rods are there—now we'll see if they will grow," whispered Koch as he slid his hanging-drop under the lens of his microscope; in a kind of stolid excitement he pulled up his chair and sat down to watch what would happen. In the gray circle of the field of his lens he could see only a few shreddy lumps of mouse spleen—they looked microscopically enormous—and here and there a very tiny rod floated among these shreds. He looked—fifty minutes out of each hour for two hours he looked, and nothing happened. But then a weird business began among the shreds of diseased spleen, an unearthly moving picture, a drama that made shivers shoot up and down his back.

The little drifting rods had begun to grow! Here were two where one had been before. There was one slowly stretching itself out into a tangled endless thread, pushing its snaky way across the whole diameter of the field of the lens—in a couple of hours the dead small chunks of spleen were completely hidden by the myriads of rods, the masses of thread that were like a hopelessly tangled ball of colorless yarn, living yarn silent murderous yarn.

"Now I know that these rods are alive," breathed Koch. "Now I see the way they grow into millions in my poor little mice—in the sheep, in the cows even. One of these rods, these bacilli—he is a billion times smaller than an ox—just one of them maybe gets into an ox, and he doesn't bear any grudge against the ox, he doesn't hate him, but he grows, this bacillus, into millions, everywhere through the big animal, swarming in his lungs and brain, choking his blood-vessels—it is terrible."

Time, his office and its dull duties, his waiting and complaining patients—all of these things became nonsense, seemed of no account, were unreal to Koch whose head was now full of nothing but dreadful pictures of the tangled skeins of the anthrax threads. Then each day of a nervous experiment that lasted eight days Koch repeated his miracle of making a million bacilli grow where only a few were before. He planted a wee bit of his rod-swarming hanging-drop into a fresh, pure drop of the watery fluid of an ox-eye and in every one of these new drops the few rods grew into myriads.

"I have grown these bacilli for eight generations away from any animal, I have grown them pure, apart from any other microbe—there is no part of the dead mouse's spleen, no diseased tissue left in this eighth hanging-drop—only the children of the bacilli that killed the mouse are in it. . . . Will these bacilli still grow in a mouse, or in a sheep, if I inject them—are these threads really the cause of anthrax?"

Carefully Koch smeared a wee bit of his hanging-drop that swarmed with the microbes of the eighth generation—this drop was murky, even to his naked eye, with countless bacilli—he smeared a part of this drop on to a little splinter of wood. Then, with that guardian angel who cares for daring stumbling imprudent searchers of nature standing by him, Koch deftly slid this splinter under the skin of a healthy mouse.

The next day Koch was bending near-sightedly over the body of this little creature pinned on his dissecting board; giddy with hope, he was carefully flaming his knives. . . . Not three minutes later Koch is seated before his microscope, a bit of the dead creature's spleen between two thin bits of glass. "I've proved it," he whispers, "here are the threads, the rods—those little bacilli from my hanging drop were just as murderous as the ones right out of the spleen of a dead sheep."

So it was that Koch found in this last mouse exactly the same kind of microbe that he had spied long before—having no idea it was alive—in the blood of the first dead cow he had peered at when his hands were fumbling and his microscope was new. It was precisely the same kind of bacillus that he had nursed so carefully, through long successions of mice, through I do not know how many hanging-drops.

First of all searchers, of all men that ever lived, ahead of the prophet Pasteur who blazed the trail for him, Koch had really made sure that one certain kind of microbe causes one definite kind of disease, that miserably small bacilli may be the assassins of formidable animals. He had angled for these impossibly tiny fish, and spied on them without knowing anything at all of their habits, their lurking places, of how hardy they might be or how vicious, of how easy it might be for them to leap upon him from the perfect ambush their invisibility gave them.

III

Cool and stolid, Koch, now that he had come through these perils, never thought himself a hero; he did not even think of publishing his experiments! To-day it would be inconceivable for a man to do such magnificent work and discover such momentous secrets, and keep his mouth shut about it.

But Koch plugged on, and it is doubtful whether this hesitating, entirely modest genius of a German country doctor

realized the beauty or the importance of his lonely experiments.

He plugged on. He must know more! He went pell-mell at the inoculating of guinea-pigs and rabbits, and at last even sheep, with the innocent looking but fatal fluid from the hanging-drops; and in each one of these beasts, in the sheep just as quickly and horribly as the mouse, the few thousands of microbes on the splinter multiplied into billions in the animals, in a few hours they teemed poisonously in what had been robust tissues, choking the little veins and arteries with their myriads, turning to a sinister black the red blood—so killing the sheep, the guinea-pigs, and the rabbits.

At one fantastic jump Koch had soared out of the vast anonymous rank and file of pill-rollers and landed among the most original of the searchers, and the more ingeniously he hunted microbes, the more miserably he tended to the important duties of his practice. Babies in far-off farms howled, but he did not come; peasants, with jumping aches in their teeth, waited sullen hours for him—and at last he had to turn over part of his practice to another doctor. Mrs. Koch saw little of him and worried and wished he would not go on his calls smelling of germicides and of his menagerie of animals. But so far as he was concerned his suffering patients and his wife might have been inhabitants of the other side of the moon—for a new mysterious question was worrying at his head, tugging at him, keeping him awake:

How, in nature, do these little weak anthrax bacilli that fade away and die so easily on my slides, how do they get from sick animals to healthy ones?

There were superstitions among the farmers and horse doctors of Europe about this disease, strange beliefs in regard to the mysterious power of this plague that hung always over their flocks and herds like some cruel invisible sword. Why, this disease is too terrible to be caused by such a wretched little creature as a twenty-thousandth-of-an-inch-long bacillus!

"Your little germ may be what kills our herds, all right, Herr Doktor," the cattle men told Koch, "but how is it that our cows or sheep can be all right in one pasture—perfectly healthy, and then, when we take them into another field, with fine grazing in it, they die like flies?"

Koch knew of this troublesome, mysterious fact too. He knew that in Auvergne in France there were green mountains, horrible mountains where no flock of sheep could go without being picked off, one by one, or in dozens and even hundreds by the black disease, anthrax. And in the country of the Beauce there were fertile fields where sheep grew fat—only to die of anthrax. The peasants shivered at night by their fires: "Our fields are cursed," they whispered.

These things bothered Koch—how could his tiny bacilli live over winter, even for years, in the fields and on the mountains? How could they, indeed, when he had smeared a little bacillus-swarming spleen from a dead mouse on a clean slip of glass, and watched the microbes grow dim, break up, and fade from view? And when he put the nourishing watery fluid of ox-eyes on these bits of glass, the bacilli would no longer grow; when he washed the dried blood off and injected it into mice—these little beasts continued to scamper gayly about in their cages. The microbes, which two days before could have killed a heavy cow, were dead!

"What keeps them alive in the fields, then," muttered Koch, "when they die on my clean glasses in two days?"

Then one day he ran on to a curious sight under his microscope—a strange transformation of his microbes that gave him a clew to his question; and Koch sat down on his stool in his eight-by-ten laboratory in East Prussia and solved the mystery of the cursed fields and mountains of France. He had kept a hanging-drop, in its closed glass well, at the temperature of a mouse's body for twenty-four hours. "Ah, this ought to be full of nice long threads of bacilli," he muttered, and looked down the tube of his microscope—"What's this?" he cried.

The outlines of the threads had grown dim, and each thread was speckled, through its whole length, with little ovals that shone brightly like infinitely tiny glass beads, and these beads were arranged along the threads as perfectly as a string of pearls.

To himself Koch muttered guttural curses. "Other microbes have doubtless gotten into my hanging-drop," he grumbled, but when he looked very carefully he saw that wasn't true, for the shiny little beads were inside the threads—the bacilli that make up the threads have turned into these beads! He dried this hanging-drop, and put it away carefully, for a month or so, and then as luck would have it, looked at it once more through his lens. The strange strings of beads were still there, shining as brightly as ever. Then an idea for an experiment got hold of him—he took a drop of pure fresh watery fluid from the eye of an ox. He placed it on the dried-up smear with its months-old bacilli that had turned into beads. His head swam with confused surprise as he looked, and watched the beads grow back into the ordinary bacilli, and then into long threads once more. It was outlandish!

"Those queer shiny beads have turned back into ordinary anthrax bacilli again," cried Koch, "the beads must be the spores of the microbe—the tough form of them that can stand great heat, and cold, and drying. . . . That must be the way the anthrax microbe can keep itself alive in the fields for so long—the bacilli must turn into spores. . . ."

Then Koch launched himself into thorough, ingenious tests to see if his quick guess was right. Expertly now he took spleens out of mice which had perished of anthrax—he lifted this deadly stuff out carefully with heated knives and forceps. Protected from all chance of contamination by stray microbes of the air, he kept the spleens for a day at the temperature of a mouse's body, and, sure enough, the microbes, every thread of them, turned into glassy spores.

Then in experiments that kept him incessantly in his dirty little room he found that the spores remained alive for months, ready to hatch out into deadly bacilli the moment he put them into a fresh drop of the watery fluid of ox-eyes, or the instant he stuck them, on one of his thin slivers, into the root of a mouse's tail.

"These spores never form in an animal while he is still alive—they only appear after he has died, and then only when he is kept very warm," said Koch, and he proved this beautifully by clapping spleens into an ice chest—and in a few days this stuff, smeared on splinters, was no more dangerous than if he had shot so much beefsteak into his mice.

It was now the year 1876, and Koch was thirty-four years old, and at last he emerged out of the bush of Wollstein, to tell the world—stuttering a little—that it was at last proved that microbes were the cause of disease. Koch put on his best suit and his gold-rimmed spectacles and packed up his microscope, a few hanging-drops in their glass cells, swarming with murderous anthrax bacilli; and besides these things he bundled a cage into the train with him, a cage that bounced a little with several dozen healthy white mice. He took a train for Breslau to exhibit his anthrax microbes and the way they kill mice, and the weird way in which they turn into glassy spores—he wanted to demonstrate these things to old Professor Cohn, the botanist at the University, who had sometimes written him encouraging letters.

Professor Cohn, who had been amazed at the marvelous experiments about which the lonely Koch had written him, old Cohn snickered when he thought of how this greenhorn doctor—who had no idea, himself, of how original he was—would surprise the highbrows of the University. He sent out invitations to the most eminent medicoes of the school to come to the first night of Koch's show.

IV

And they came. To hear the unscientific backwoodsman—they came. They came maybe out of friendliness to old Professor Cohn. But Koch didn't lecture—he was never much at talking—instead of telling them that his microbes were the true cause of anthrax, he showed these sophisticated professors. For three days and nights he showed them, taking them in swift steps through those searchings he had sweated at—groping and failing often—for years. Never was there a greater come-down for bigwigs who had arrived prepared to be indulgent to a nobody. Koch never argued once, he never bubbled and raved and made prophecies—but he slipped slivers into mouse tails with an unearthly cleverness, and the experienced professors of pathology opened their eyes to see him handle his spores and bacilli and microscopes like a sixty-year-old master. It was a knock-out!

At last Professor Cohnheim, one of the most skillful scientists in the study of diseases in all of Europe, could hold himself no longer. He rushed from the hall, hurried to his own laboratory, and burst into the room where his young student searchers were working. He shouted to them: "My boys, drop everything and go see Doctor Koch—this man has made a great discovery!" Cohnheim gasped to get his breath.

"But who is this Koch, Herr Professor? We’ve never even heard of him."

"No matter who he is—it is a great discovery, so exact, so simple. It is astounding! This Koch is not a professor, even. . . . He hasn’t even been taught how to do research! He's done it all by himself, complete—there is nothing more to do!"

"But what is this discovery, Herr Professor?"

"Go, I tell you, every one of you, and see for yourselves. It is the most marvelous discovery in the realm of microbes . . . he will make us all ashamed of ourselves. . . . Go" But by this time, all of them, including Paul Ehrlich, had disappeared through the door.

Seven years before, Pasteur had foretold: "It is within the power of man to make parasitic maladies disappear from the face of the earth. . . ." And when he said these words the wisest doctors in the world put their fingers to their heads, thinking: "The poor fellow is cracked!"

But this night Robert Koch had shown the world the first step toward the fulfillment of Pasteur’s seemingly insane vision: "Tissues from animals dead of anthrax, whether they are fresh, or putrid, or dried, or a year old, can only produce anthrax when they contain bacilli or the spores of bacilli. Before this fact all doubt must be laid aside that these bacilli are the cause of anthrax," he told them finally, as if his experiments had not convinced them already. And he ended by telling his amazed audience how to fight this terrible disease—how his experiments showed a way to stamp it out in the end: "All animals that die of anthrax must be destroyed at once after they die—or if they can not be burned, they should be buried deep in the ground, where the earth is so cold that the bacilli cannot turn into the tough, long-lived spores. . . ."

So it was that in these three days at Breslau this Koch put a sword Excalibur into the hands of men, with which to begin the fight against their enemies the microbes, their fight against lurking death; so it was that he began to change the whole business of doctors from a foolish hocus-pocus with pills and leeches into an intelligent fight where science instead of superstition was the weapon.

Koch fell among friends—among honest generous men—at Breslau. Cohn and Cohnheim, instead of trying to steal his stuff (there are no fewer shady fellows in science than in any other human activity), these two professors immediately set up a great whooping for Koch, an applause that echoed over Europe and made Pasteur a bit uneasy for his job as Dean of the Microbe Hunters. These two friends began to bombard the authorities of the Imperial Health Office at Berlin about this unknown that Germany ought to be proud of—they did their best to give Koch a chance to do nothing but chase the microbes of disease, to get away from that dull practice of his.

Left alone, or snubbed at Breslau, he might easily have gone back to Wollstein to his business of telling people to stick out their tongues. In short, men of science have either to be showmen—as were the magnificent Spallanzani and the passionate Pasteur—or they have to have impresarios.

Koch packed up Emmy and his household goods and moved to Breslau and was given a job as city physician at four hundred and fifty dollars a year, and was supposed to eke out his living with the private patients that would undoubtedly flock to be treated by such a brilliant man.

So thought Cohn and Cohnheim. But the doorbell of Koch's little office didn't ring, hardly any one came to ring it, and so Koch learned that it is a great disadvantage for a doctor to be brainy and inquire into the final causes of things. He went back to Wollstein, beaten, and here from 1878 to 1880 he made long jumps ahead in microbe hunting once more—spying on and tracking down the strange sub-visible beings that cause the deadly infections of wounds in animals and in human beings. He learned to stain all kinds of bacilli with different colored dyes, so that the very tiniest microbe would stand out clearly. In some unknown way he saved money enough to buy a camera and stuck its lens against his microscope and learned—no one helping him—how to take pictures of these little creatures.

"You'll never convince the world about these murderous bugs until you can show them photographs," Koch said. "Two men can't look through one microscope at the same time, no two men will ever draw the same picture of a germ—so there'll always be wrangling and confusion. . . . But these photographs can't lie—and ten men can study them, and come to an agreement on them. . . ." So it was that Koch began to try to introduce rime and reason into the baby science of microbe hunting which up till now had been as much a wordy brawl as a quest for knowledge.

Meanwhile his friends at Breslau had not forgotten him and in 1880—it was like some bush-leaguer breaking into the big team—he was told by the government to come to Berlin and be Extraordinary Associate of the Imperial Health Office. Here he was given a fine laboratory and a sudden undreamed-of wealth of apparatus and two assistants and enough money so that he could spend sixteen or eighteen hours of his working day among his stains and tubes and chittering guinea-pigs.

By this time the news of Koch's discoveries had spread to all of the laboratories of Europe and had crossed the ocean and inflamed the doctors of America. The vast exciting Battle of the Germ Theory was on! Every medical man and Professor of Diseases who knew—or thought he knew—the top end from the bottom of a microscope set out to become a microbe hunter. Every week brought glad news of the supposed discovery of some new deadly microbe, surely the assassin of suffering from cancer or typhoid fever or consumption. One enthusiast would shout across continents that he had discovered a kind of pan-germ that caused all diseases from pneumonia to the pip—only to be forgotten for an idiot who might claim that he had proved one disease, let us say consumption, to be the result of the attack of a hundred different species of microbes.

So great was the enthusiasm about germs—and the confusion—that Koch's discoveries were in danger of being laughed into obscurity along with the vast magazines full of balderdash that were being printed on the subject of the germ theory.

And yet to-day we demand with a great hue and cry more laboratories, more microbe hunters, better paid searchers to free us from the diseases that scourge us. How futile! For progress, God must send us a few more infernal marvelous searchers of the kind of Robert Koch.

But in the midst of the danger that foolish enthusiasm would kill the new science of microbe hunting, Koch kept his head, and sat down to find a way to grow germs pure. "One germ, one kind of germ only, causes one definite kind of disease—every disease has its own specific microbe, I know that," said Koch—without knowing it. "I've got to find a sure easy method of growing one species of germ away from all other contaminating ones that are always threatening to sneak in!"

But how to cage one kind of microbe? All manner of weird machines were being invented to try to keep different sorts of germs apart. Several microbe hunters devised apparatus so complicated that when they had finished building it they probably had already forgotten what they set out to invent it for. To keep stray germs of the air from falling into their bottles some heroic searchers did their inoculations in an actual rain of poisonous germicides!

V

Until, one day, Koch—who frankly admitted it was by accident—looked at the flat surface of half of a boiled potato left on a table in his laboratory. "What's this, I wonder?" he muttered, as he stared at a curious collection of little colored droplets scattered on the surface of the potato. "Here's a gray colored drop, here's a red one, there's a yellow, a violet one—these little specks must be made up of germs from the air. I'll have a look at them."

He stuck his short-sighted eyes down close to the potato so that his scraggly little beard almost dragged in it; he got ready his thin plates of glass and polished off the lenses of his microscope.

With a slender wire of platinum he fished delicately into one of the gray droplets and put a bit of its slimy stuff in a little pure water between two bits of glass, under his microscope. Here he saw a swarm of bacilli, swimming gently about, and every one of these microbes looked exactly like his thousands of brothers in this drop. Then Koch peered at the bugs from a yellow droplet on the potato, and at those of a red one and a violet one. The germs from one were round, from another they had the appearance of swimming sticks, from a third microbes looked like living corkscrews—but all the microbes in one given drop were like their brothers, invariably!

Then in a flash Koch saw the beautiful experiment nature had done for him. "Every one of these droplets is a pure culture of one definite kind of microbe—a pure colony of one species of germs. . . . How simple! When germs fall from the air into the liquid soups we have been using—the different kinds of them get all mixed up and swim among each other. . . . But when different bugs fall from the air on the solid surface of this potato—each one has to stay where it falls . . . it sticks there . . . then it grows there, multiplies into millions of its own kind . . . absolutely pure!"

Koch called Loeffler and Gaffky, his two military doctor assistants, and soberly he showed them the change in the whole mixed-up business of microbe hunting that his chance glance at an abandoned potato had brought. It was revolutionary! The three of them set to work with an amazing—loyal Frenchmen might call it stupid—German thoroughness to see if Koch was right. There they sat before the three windows of their room, Koch before his microscope on a high stool in the middle, Loeffler and Gaffky on stools on his left hand and his right—a kind of grimly toiling trinity. They tried to defeat their hopes, but quickly they discovered that Koch's prophecy was an even more true one than he had dreamed. They made mixtures of two or three kinds of germs, mixtures that could never have been untangled by growing in flasks of soup; they streaked these confused species of microbes on the cut flat surfaces of boiled potatoes. And where each separate tiny microbe landed, there it stuck, and grew into a colony of millions of its own kind—and nothing but its own kind.

Now Koch, who, by this simple experience of the old potato, had changed microbe hunting from a guessing game into something that came near the sureness of a science—Koch, I say, got ready to track down the tiny messengers that bring a dozen murderous diseases to mankind. Up till this time Koch had bad very little criticism or opposition from other men of science, mainly because he almost never opened his mouth until he was sure of his results. He told of his discoveries with a disarming modesty and his work was so unanswerably complete—he had a way of seeing the objections that critics might make and replying to them in advance—that it was hard to find protestors.

Full of confidence Koch went to Professor Rudolph Virchow, by far the most eminent German researcher in disease, an incredible savant, who knew more than there was to be known about a greater number of subjects than any sixteen scientists together could possibly know. Virchow was, in brief, the ultimate Pooh-Bah of German medical science. He had spoken the very last word on clots in blood vessels and had invented the impressive words, heteropopia, agenesia, and ochronosis, and many others that I have been trying for years to understand the meaning of. He had—with tremendous mistakenness—maintained that consumption and scrofula were two different diseases; but with his microscope he had made genuinely good, even superb descriptions of the way sick tissues look and he had turned his lens into every noisome nook and cranny of twenty-six thousand dead bodies. Virchow had printed—I do not exaggerate—thousands of scientific papers, on every subject imaginable, from the shapes of little German schoolboys' heads and noses to the remarkably small size of the blood vessels in the bodies of sickly green-faced girls.

Properly awed—as any one would be—Koch tiptoed respectfully into this Presence.

"I have discovered a way to grow microbes pure, unmixed with other germs, Herr Professor," the bashful Koch told Virchow, with deference.

"And how, I beg you tell me, can you do that? It looks to me to be impossible."

"By growing them on solid food—I can get beautiful isolated colonies of one kind of microbe on the surface of a boiled potato. . . . And now I have invented a better way than that . . . I mix gelatin with beef broth . . . and the gelatin sets and makes a solid surface, and"

But Virchow was not impressed. He made a sardonic remark that it was so hard to keep different races of germs from getting mixed up that Koch would have to have a separate laboratory for each species of microbe. . . . In short, Virchow was very sniffish and cold to Koch, for he had come to that time of life when ageing men believe that everything is known and there is nothing more to be found out. Koch went away a bit depressed, but not one jot was he discouraged. Instead of arguing and writing papers and making speeches against Virchow he launched himself into the most exciting and superb of all his microbe huntings—he set out to spy upon and discover the most vicious of microbes, that mysterious marauder which each year killed one man, woman, and child out of every seven that died, in Europe, in America. Koch rolled up his sleeves and wiped his gold-rimmed glasses and set out to hunt down the microbe of tuberculosis.

VI

Compared to this sly murderer the bacillus of anthrax had been reasonably easy to discover—it was a large bug as microbes go, and the bodies of sick animals were literally alive with anthrax germs when the beasts were about to die. But this tubercle germ—if indeed there was such a creature—was a different matter. Many searchers were looking in vain for it. Leeuwenhoek, with his sharpest of all eyes, would never have found it even if he had looked at a hundred sick lungs; Spallanzani's microscopes would not have been good enough to have revealed this sly microbe; Pasteur, searcher that he was, had neither the precise methods of searching, nor, perhaps, the patience, to lay bare this assassin.

All that was known about tuberculosis was that it must be caused by some kind of microbe, since it could be transmitted from sick men to healthy animals. An old Frenchman, Villemin, had pioneered in this work, and Cohnheim, the brilliant professor of Breslau, had found that he could give tuberculosis to rabbits—by putting a bit of the consumptive's sick lung into the front chamber of a rabbit's eye. Here Cohnheim could watch the little islands of sick tissue—the tubercles—spread and do their deadly work; it was a strange clever experiment that was like looking through a window at a disease growing. . . .

Koch had studied Cohnheim's experiments closely. "This is what I need," he meditated. "I may not use human beings for experimental animals, but now I can give the disease, whenever I wish, to animals . . . here is a real chance to study it, handle it, to look for the microbe that must cause it . . . there must be a microbe there. . . ."

So Koch set to work—he did everything with a cold system that gives one the shivers when one reads his scientific reports—and he got his first consumptive stuff from a powerful man, a laborer aged thirty-six. This man had been superbly healthy three weeks before, when all at once he began to cough, little pains shot through his chest, his body seemed literally to melt away. Four days after this poor fellow entered the hospital, he was dead, riddled with tubercles—every organ was peppered with little grayish-yellow, millet-seed-like specks

With this dangerous stuff Koch set to work, alone, for Loeffler had set out to track down the microbe of diphtheria and Gaffky was busy trying to find the sub-visible author of typhoid fever. Koch, meanwhile, crushed the yellowish tubercles from the body of the dead man between two heated knives; he ground these granules up and delicately, with a little syringe, injected them into the eyes of numerous rabbits and under the skins of flocks of foolish guinea-pigs. He put these beasts in clean cages and tended them lovingly. And while he waited for his creatures to develop signs of the consumption, he began to peer with his most powerful microscope through the sick tissues that he had taken from the body of the dead workman.

For days he saw nothing. His best lenses, that magnified many hundred times, showed him only the dead ruins of what had once been good healthy lung or liver. "If there is a tubercle microbe, he is such a sneaky fellow that I won’t be able, perhaps, to see him in his native state. But I can try painting the tissue with a powerful dye—that may make this bug stand out. . . ."

Day after day, Koch set about staining the stuff from the dead workman brown and blue and violet and most of the colors of the rainbow. Carefully, dipping his hands in the germ-killing bichloride of mercury after almost every move—blackening and wrinkling them with it—he smeared the perilous material from the tubercles on thin clean bits of glass and kept these pieces of glass for hours in a strong blue dye. . . .

Then one morning he took his specimens out of their bath of stain, and put them under his lens, and focussed his microscope and out of the gray mist a strange picture untangled itself. Lying among the shattered diseased lung cells were curious masses of little, infinitely thin bacilli—blue colored rods—so slim that he could not guess their size, and they were less than a fifteen-thousandth of an inch long.

"Ah! they are pretty," he muttered. "They're not straight like the anthrax bugs . . . they have little bends and curves in them. Wait! here are whole bunches of them . . . like cigarettes in a pack—Heh! here is one lone devil inside a lung cell . . . I wonder . . . have I found him—that tubercle bug, already?"

Koch went on, precisely, with that efficiency of his, to staining tubercles from every part of the workman's body, and everywhere his blue dye showed up these same slender crooked bacilli—strange creatures unlike any he had seen in all the thousands of animals or men, diseased or healthy, into whose insides he had pried. And now, sorry things began to happen to his inoculated guinea-pigs and rabbits. The guinea-pigs began to huddle disconsolately in the corners of their cages; their sleek coats ruffled and their bouncing little bodies began to fall away until they were sad bags of bones. They were feverish, their cavortings stopped and they looked listlessly at their fine carrots and their fragrant meals of hay—and one by one they died. And as these unconscious martyrs died—for Koch's mad curiosity and for suffering men—the little microbe hunter pinned them down on his post-mortem board and soaked their sick hair with bichloride of mercury and precisely and with breathless care cut them open with sterile knives.

And inside these poor beasts Koch found the same kind of grayish-yellow sinister tubercles that had filled the body of the workman. Into the baths of blue stain on his eternal strips of glass Koch dipped them—and everywhere, in every one, he found the same terrible curved sticks that had jumped into his astounded gaze when he had stained the lung of the dead man.

"I have it!" he whispered, and called the busy Loeffler and the faithful Gaffky from their own spyings on other microbes. "Look!" Koch cried. "One little speck of tubercle I put into this beast six weeks ago—there could not have been more than a few hundred of those bacilli in that small bit—and now they've grown into billions! What devils they are, those germs—from that one place in the guinea-pig's groin they have sneaked everywhere into his body, they have gnawed—they have grown through the walls of his arteries . . . the blood has carried them into his bones . . . into the farthest corner of his brain. . . ."

Now he went to hospitals everywhere in Berlin, and begged the bodies of men or women that had died of consumption, he spent dreary days in dead houses and every evening before his microscope in his laboratory where the stillness was broken only by the eerie purrings and scurryings of guinea-pigs. He injected the sick tissue from the wasted bodies of consumptives who had died, into hundreds of guinea-pigs, into rabbits and three dogs, thirteen scratching cats, ten flopping chickens and twelve pigeons. He didn't stop with these wholesale insane inoculations but shot the same kind of deadly cheesy stuff into white mice and rats and field mice and into two marmots. Never in microbe hunting has there been such appalling thoroughness.

"Ach! this is a little hard on the nerves, this work," he muttered (thinking, perhaps of the lightning move of the paw of one of his cats jabbing the germ-filled syringe needle into his own hand). For Koch, hunting his invisible foes alone, there were so many disagreeable and always imminent possibilities of excitement—of something tragically worse than mere excitement. . . .

But the hand of this completely unheroic looking little microbe hunter never slipped, it just grew drier and more wrinkled and blacker from its incessant baths in the bichloride of mercury—that good bichloride, with which in those old days the groping microbe hunters used to swab down everything, including their own persons. Then, week by week, in all of Koch's meaouwing, crowing, barking, clucking menagerie of beasts those small curved bacilli grew into their relentless millions—and one by one the animals died, and gave eighteen-hour-days of work to Robert Koch in post-mortems and blear-eyed peerings through the microscope.

"It is only when a man or beast has tuberculosis that I can find these blue-stained rods, these bacilli," Koch told Loeffler and Gaffky. "In healthy animals—I have looked, you know, at hundreds of them—I never find them."

"That means, without doubt, that you have discovered the bacillus that is the cause, Herr Doktor"

"No—not yet—what I have done might make Pasteur sure, but I am not at all convinced yet. . . . I have to get these bacilli out of the bodies of my dying animals now . . . grow them on our beef broth jelly, pure colonies of these microbes I must get, and cultivate them for months, away from any living creature . . . and then, if I inoculate these cultivations into good healthy animals, and they get tuberculosis . . ." and Koch's sober wrinkled face smiled for a moment. Loeffler and Gaffky, ashamed of their jumping at conclusions, went back awed to their own searchings.

Testing every possible combination that his head could invent, Koch set out to try to grow his bacilli pure on beef-broth jelly. He made a dozen different kinds of good soup for them, he kept his tubes and bottles at the temperature of the room and the temperature of a man's body and the temperature of fever. He cleverly used the sick lungs of guinea-pigs that teemed with bacilli, lungs that held no other stray microbes which might over-grow and choke out those delicate germs which he was sure must be the authors of consumption. The stuff from these lungs he planted dangerously into hundreds of tubes and bottles, but all this work ended in—nothing. In brief, those slim bacilli that grew like weeds in tropic gardens in the bodies of his sick animals, those microbes that swarmed in millions in sick men, those bacilli turned up their noses—that is, they would have if they had been equipped with noses—at the good soups and jellies that Koch cooked for them. It was no go!

But one day a reason for his failures popped into Koch's head: "The trouble is that these tubercle bacilli will only grow in the bodies of living creatures—they are maybe almost complete parasites—I must fix a food for them that is as near as possible like the stuff a living animal's body is made of!"

So it was that Koch invented his famous food—blood-serum jelly—for microbes that are too finicky to grow on common provender. He went to string-butchers and got the clear straw-colored serum from the clotted blood of freshly slaughtered healthy cattle and carefully heated this fluid to kill all the stray microbes that might have fallen into it. Delicately he poured this serum into each one of dozens of narrow test-tubes, and placed these on a slant so that there would be a long flat surface on which to smear the sick consumptive tissues. Then ingeniously he heated each tube just hot enough to make the serum set, on a slant, into a clear beautiful jelly.

That morning a guinea-pig, sadly riddled with tuberculosis, had died. He dissected out of it a couple of the grayish yellow tubercles, and then, with a wire of platinum he streaked bits of this bacillus-swarming stuff on the moist surface of his serum jelly, on tube after tube of it. Then, with that drawing in and puffing out of breath that comes after a nasty piece of work, well done, Koch took his tubes and put them in the oven—at the exact temperature of a guinea-pig's body.

Day after day Koch hurried in the morning to his incubating oven, and took out his tubes and held them close to his gold-rimmed glasses, and saw—nothing.

"Well, I have failed again," he mumbled—it was the fourteenth day after he had planted his consumptive stuff—"every other microbe I have ever grown multiplies into large colonies in a couple of days, but here, confound it—there is nothing, nothing . . ."

Any other man would have pitched these barren disappointing serum-tubes out, but at this stubbly-haired country doctor's shoulder his familiar demon whispered: "Wait—be patient, my master—you know that tubercle germs sometimes take months, years to kill men. Maybe too they grow very slowly in the serum tubes." So Koch did not pitch the tubes out, and on the morning of the fifteenth day he came back to his incubator—to find the velvety surface of the serum jelly covered with tiny glistening specks! Koch reached a trembling hand for his pocket lens, clapped it to his eye and peered at one tube after another, and through his lens these glistening specks swelled out into dry tiny scales. . . .

In a daze Koch pulled the cotton plug out of one of his tubes, mechanically he flamed its mouth in the sputtering blue fire of the Bunsen burner, with a platinum wire he picked off one of these little flaky colonies—they must be microbes—and not knowing how or what, he got them before his microscope. . . .

Then he knew that he had got to a warm inn on the stony road of his adventure—here they were, countless myriads of these same bacilli, these crooked rods that he had first spied in the lung of the dead workman. They were motionless but surely multiplying and alive—they were delicate and finicky about their food and feeble in size, but more savage than hordes of Huns and more murderous than ten thousand nests of rattlesnakes.

Now Koch, in taut intent months, confirmed his first success—he went after proving it with a patience and a detail that made me sick of his everlasting thoroughness and prudence as I read the endlessly multiplied experiments in his classic report on tuberculosis—from consumptive monkeys and consumptive oxen and consumptive guinea-pigs Koch grew forty-three different families of these deadly rods on his slanted tubes of serum jelly!

And only from animals sick or dying of tuberculosis, could he grow them. For months he nursed these wee murderers along, planting them from one tube to another—with marvelous watchfulness he kept all other chance microbes away from them.

"Now I must shoot these bacilli—these pure cultivations of my bacilli—into healthy guinea-pigs, into all kinds of healthy animals. If then these creatures get tuberculosis, I shall know that my bacilli are necessarily and beyond all doubt the cause!"

That man with the terrible single-mindedness of a maniac driven by a fixed idea changed his laboratory into the weirdest kind of zoo. He became grouchy to every one—to curious visitors he was a sarcastic, spiteful little German ogre. Alone he sterilized batteries of shining syringes and shot the crinkly masses of microbes from the cultivations in his serum-jelly tubes—he injected these bacilli ground up in a little pure water into guinea-pigs and rabbits and hens and rats and mice and monkeys. "That's not enough!" he growled, "I'll try some animals that never are known to have tuberculosis naturally." So he ranged abroad and gathered to his laboratory and injected his beloved terrible bacilli into tortoises, sparrows, five frogs and three eels.

Insanely Koch completed this most fantastic test by sticking his microbes from the serum cultivation into—a goldfish!

Days dragged by, weeks passed, and every day Koch walked into his workshop in the morning and made straight for the cages and jars that held these momentous animals. The goldfish continued to open and shut his mouth and swim placidly about in his round-bellied bowl. The frogs croaked unconcernedly and the eels kept all of their slippery liveliness; the tortoise now and then stuck his head out of his shell and seemed to wink an eye at Koch as if to say: "Your tubercle bugs are food for me—give me some more."

But while his injections worked no harm to these creatures, that do not in the course of nature get consumption anyway—at the same time the guinea-pigs began to droop, to lie pitifully on their sides, gasping. One by one they died, their bodies wasting terribly into tubercles. . . .

Now Koch had forged the last link of the chain of his experiments and was ready to give his news to the world: The bacillus, the true cause of tuberculosis, has been trapped, discovered! When suddenly he decided there was one more thing to do.

"Human beings surely must catch these bacilli by inhaling them, in dust, or from the coughing of people sick with consumption. I wonder, will healthy animals be infected that way too?" At once Koch began to devise ways of doing this experiment—it was a nasty job. "I'll have to spray the bacilli from my cultivations at the animals," he pondered. But this was a more serious business than turning ten thousand murderers out of jail. . . .

Like the good hunter that he was, he took a chance with the dangers that he couldn't avoid. He built a big box and put guinea-pigs and mice and rabbits inside it and set this box in the garden. Then through the window he ran a lead pipe that opened in a spray nozzle inside the box, and for three days, for half an hour each day, he sat in his laboratory, pumping at a pair of bellows that shot a poisonous mist of bacilli into the box—to be breathed by the cavorting beasts inside it.

In ten days three of the rabbits were gasping, fighting for that precious air that their sick lungs could no longer give them. In twenty-five days the guinea-pigs had done their humble work—one and all they were dead, of tuberculosis.

Koch told nothing of the ticklish job it was to take these beasts out of their germ-soaked box—if I had been in his place I would rather have handled a boxful of boa-constrictors—and he makes no mention of how he disposed of this little house whose walls had been wet with this so-deadly spray. What chances for making heroic flourishes were missed by this quiet Koch!

VII

On the twenty-fourth of March in 1882 in Berlin there was a meeting of the Physiological Society in a plain small room made magnificent by the presence of the most brilliant men of science in Germany. Paul Ehrlich was there and the most eminent Professor Rudolph Virchow—who had but lately sniffed at this crazy Koch and his alleged bacilli of disease—and nearly all of the famous German battlers against disease were there.

A bespectacled wrinkled small man rose and put his face close to his papers and fumbled with them. The papers quivered and his voice shook a little as he started to speak. With an admirable modesty Robert Koch told these men the plain story of the way he had searched out the invisible assassin of one human being out of every seven that died. With no oratorical raisings of his voice he told these disease fighters that the physicians of the world were now able to learn all of the habits of this bacillus of tuberculosis—this smallest but most savage enemy of men. Koch recited to them the lurking places of this slim microbe, its strengths and weaknesses, and he showed them how they might begin the fight to crush, to wipe out this sub-visible deadly enemy.

At last Koch sat down, to wait for the discussion, the inevitable arguments and objections that greet the finish of revolutionary papers. But no man rose to his feet, no word was spoken, and finally eyes began to turn toward Virchow, the oracle, the Tsar of German science, the thunderer whose mere frown had ruined great theories of disease.

All eyes looked at him, but Virchow got up, put on his hat, and left the room—he had no word to say.

If old Leeuwenhoek, two hundred years before, had made so astounding a discovery, Europe of the Seventeenth Century would have heard the news in months. But in 1882 the news that Robert Koch had found the microbe of tuberculosis trickled out of the little room of the Physiological Society the same evening, sang to Kamchatka and to San Francisco on the cable wires that night, and exploded on the front pages of the newspapers in the morning. Then the world went wild over Koch, doctors boarded ships and hopped trains for Berlin to learn from him the secret of hunting microbes; vast crowds of them rushed to Berlin to sit at Koch's feet to learn how to make beef-broth jelly and how to stick syringes full of germs into the wiggling carcasses of guinea-pigs.

Pasteur's deeds had set France by the ears, but Koch's experiments with the dangerous tubercle bacilli rocked the earth, and Koch waved worshipers away, saying:

"This discovery of mine is not such a great advance."

He tried to get away from his adorers and to dodge his eager pupils, to snatch what moments he could for his own new searchings. He loathed teaching—that way he was precisely like Leeuwenhoek—but he was forced, cursing under his breath, to give lessons in microbe hunting to Japanese who spoke horrible German and understood less than they spoke, and to Portuguese, who could never, by any amount of instruction, learn to hunt microbes. He started a huge fight with Pasteur—but of this I shall tell in the next chapter—and between times he showed his assistant, Gaffky, how to spy on and track down the bacillus of typhoid fever. He was forced to attend idiotic receptions and receive medals, and came away from these occasions to guide his fierce-mustached assistant Loeffler, who was on the trail of the poison-dripping microbe that kills babies with diphtheria. It was thus that Koch shook the tree of his marvelous simple method of growing microbes on the surface of solid food—he shook the tree, as Gaffky said long afterward, and discoveries rained into his lap.

In all of his writings I have never found any evidence that Koch considered himself a great originator; never, like Pasteur, did he seem to realize that he was the leader in the most beautiful and one of the most thrilling battles of men against cruel nature—there was no actor in this mussy-bearded little man. But he did set under way an inspiring drama, a struggle with the messengers of death that turned some of the microbe-hunting actors into maniac searchers, men who went to nearly suicidal lengths, almost murderous extremes—to prove that microbes were the cause of dangerous diseases.

Doctor Fehleisen, to take one instance, went out from Koch's laboratory and found a curious little ball-shaped microbe, hitched to its brothers in chains like the beads of a rosary—he cultivated these bugs from skin gouged out of people sick with erysipelas, that sky-rockety disease that used to be called St. Anthony's Fire. On the theory that an attack of erysipelas might cure cancer—a mad man's excuse!—Fehleisen shot billions of these chain microbes, now known as streptococci, into people hopelessly sick with cancer. And in a few days each one of these human experimental animals of his flamed red with St. Anthony's Fire—some collapsed dangerously and nearly died—and so this desperado proved his case: That streptococcus is the cause of erysipelas.

Another pupil of Koch was the now forgotten hero, Doctor Garrè of Basel, who gravely rubbed whole test-tubes full of another kind of microbe—which Pasteur had alleged was the cause of boils—into his own arm. Garrè came down horribly with an enormous carbuncle and twenty boils—the tremendous dose of microbes he shot into himself might easily have finished him—but he dismissed his danger as merely "unpleasant" and shouted triumphantly: "I now know that this microbe, this staphylococcus, is the true cause of boils and carbuncles!"

Meanwhile, at the end of 1882, when Koch had finished his virulent and partly comic wrangle with Pasteur, who was just then with prodigious enthusiasm saving the lives of sheep and cattle in France, the discoverer of the tubercle bacillus started sniffing along the trail of one of the most delicate, the most easy to kill, and yet the most terribly savage of all microbes. In 1883 the Asiatic cholera knocked at the door of Europe. This cholera had stolen out of its lurking place in India and slipped mysteriously across the sea and over desert sands to Egypt; suddenly a murderous epidemic of it exploded in Alexandria and Europe across the Mediterranean was frightened. In Alexandria the streets were still with fear; the murderous virus—no one had the slightest notion of what kind of an invisible beast it was—this virus, I say, sneaked into healthy men in the morning, doubled them into knots of spasm-racked agony by afternoon, and put them to rest beyond the reach of all pain by night.

Then a strange race started between Pasteur and Koch, which meant between France and Germany, to search out the microbe of this cholera that flared threatening on the horizon. Koch and Gaffky went armed with microscopes and a menagerie of animals from Berlin; Pasteur—who was desperately busy struggling to conquer the mysterious microbe of hydrophobia—sent the brilliant and devoted Émile Roux and the silent Thuillier, youngest of the microbe hunters of Europe. Koch and Gaffky worked forgetting to eat or sleep; they toiled in dreadful rooms cutting up the bodies of Egyptians dead of cholera; in their muggy laboratory with the air fairly dripping with a steamy heat, sweat dropping off the ends of their noses on to the lenses of their microscopes, they shot stuff from the tragic carcasses of just-dead Alexandrians into apes and dogs and hens and mice and cats. But while these rival teams of searchers hunted frantically the epidemic began to fade away as mysteriously as it came. None of them had yet found a microbe they could surely accuse, and all of them—there is a kind of twisted humor in this—grumbled as they saw death receding, their chance of trapping their prey slipping from them.

Koch and Gaffky were getting ready to return to Berlin, when one morning a frightened messenger came to them and told them: "Dr. Thuillier, of the French Commission, is dead—of cholera."

Koch and Pasteur hated each other sincerely and enthusiastically, like the good patriots that they were, but now the two Germans went to the bereaved Roux and offered their help and their condolences; and Koch was one of those that carried in a plain box to its last home the body of Thuillier, this daring young Thuillier whom the miserably weak—but treacherous—cholera microbe had turned upon and done to death before he had ever had a chance to spy upon and trap it. At the grave Koch laid wreaths upon the coffin: "They are very simple," he said, "but they are of laurel, such as are given to the brave."

The funeral of this first of the martyred microbe hunters over, Koch hurried back to Berlin with certain mysterious boxes that held specimens, that he had painted with powerful dyes, and these specimens had in them a curious microbe shaped like a comma. Koch made his report to the Minister of State: "I have found a germ," he said, "in all cases of cholera . . . but I haven't proved yet that it is the cause. Send me to India where cholera is always smoldering—what I have found justifies your sending me there."

So Koch sailed from Berlin for Calcutta, with the fate of Thuillier hanging over him, drolly chaperoning fifty mice and dreadfully annoyed by seasickness. I have often wondered what his fellow-passengers took him for—probably they guessed that he was some earnest little missionary or a serious professor intent to delve into ancient Hindu lore.

Koch found his comma bacillus in the dead bodies of every one of the forty carcasses into which he peered, and he unearthed the same microbe in the intestines of patients at the moment the fatal disease hit them. But he never found this germ in any of the hundreds of healthy Hindus that he examined, nor in any animal, from mice to elephants.

Quickly Koch learned to grow the comma bacillus pure on beef-broth jelly, and once he had it imprisoned in his tubes he studied all the habits of this vicious little vegetable, how it perished quickly when he dried it the least bit, how it could sneak into a healthy man by way of the soiled linen of patients that had died. He dredged this comma microbe up out of the stinking water of the tanks around which clustered the miserable Hindu's huts—sad hovels from which drifted the moans of helpless ones that were dying of cholera.

At last Koch sailed back to Germany, and here he was received like some returning victorious general. "Cholera never rises spontaneously," he told his audience of learned doctors; "no healthy man can ever be attacked by cholera unless he swallows the comma microbe, and this germ can only develop from its like—it cannot be produced from any other thing, or out of nothing. And it is only in the intestine of man, or in highly polluted water like that of India that it can grow."

It is thanks to these bold searchings of Robert Koch that Europe and America no longer dread the devastating raids of these puny but terrible little murderers from the Orient—and their complete extermination from the world waits only upon the civilization and sanitation of India. . . .

VIII

From the German Emperor's own hand Koch now received the Order of the Crown, with Star, but in spite of that his countrified hat continued to fit his stubbly head, and when admirers adored him he only said to them: "I have worked as hard as I could . . . if my success has been greater than that of most . . . the reason is that I came in my wanderings through the medical field upon regions where the gold was still lying by the wayside . . . and that is no great merit."

The hunters who believed that microbes were the chief foes of man, these men were brave, but there was careless heroism too among some of the ancient doctors and old-fogey sanitarians who thought that all this new stuff about microbes was claptrap and nonsense. Old Professor Pettenkofer of Munich was the leader of the skeptics who were not convinced by Koch's clear experiments, and when Koch came back from India with those comma bacilli that he was sure were the authors of cholera Pettenkofer wrote him something like this: "Send me some of your so-called cholera germs, and I'll show you how harmless they are!"

Koch sent him on a tube that swarmed with wee virulent comma microbes. And so Pettenkofer—to the great alarm of all good microbe hunters—swallowed the entire contents of the tube. There were enough billions of wiggling comma germs in this tube to infect a regiment. Then he growled his scorn through his magnificent beard, and said: "Now let us see if I get cholera!" Mysteriously, nothing happened, and the failure of the mad Pettenkofer to come down with cholera remains to this day an enigma, without even the beginning of an explanation.

Pettenkofer, who was foolhardy enough to try such a possibly suicidal experiment, was also sufficiently cocksure to believe that his drinking of the cholera soup had settled the question in his favor. "Germs are of no account in cholera!" shouted the old doctor. "The important thing is the disposition (whatever that means) of the individual!"

"There can be no cholera without the comma bacillus!" said Koch in reply.

"But I have just swallowed millions of your alleged fatal bacilli, and have not even had a cramp in my stomach!" came back Pettenkofer in rebuttal.

As it is so often the case, alas, in violent scientific controversies, both sides were partly right and partly wrong. Every event of the past forty years has shown that Koch was right when he said that people can never have cholera without swallowing his comma bacillus. And the years that have gone by have revealed that Pettenkofer's experiment pointed out a mystery behind the curtains of the unknown, and these obscuring draperies have not now even begun to be lifted by modern microbe hunters. Murderous germs are everywhere, sneaking into all of us, yet they are able to assassinate only some of us, and that question of the strange resistance of the rest of us is still just as much an unsolved puzzle as it was in those days of the roaring eighteen-eighties when men were ready to risk dying to prove that they were right.

For, make no mistake, Pettenkofer walked within an inch of death; other microbe hunters have since then swallowed cultures of virulent cholera microbes by accident—and died horribly.