Microbe Hunters/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

PASTEUR

MICROBES ARE A MENACE!

I

In 1831, thirty-two years after the magnificent Spallanzani died, microbe hunting had come to a standstill once more. The sub-visible animals were despised and forgotten while other sciences were making great leaps ahead; clumsy horribly coughing locomotives were scaring the horses of Europe and America; the telegraph was getting ready to be invented. Marvelous microscopes were being devised, but no man had come to squint through these machines—no man had come to prove to the world that miserable little animals could do useful work which no complicated steam engine could attempt; there was no hint of the somber fact that these wretched microbes could kill their millions of human beings mysteriously and silently, that they were much more efficient murderers than the guillotine or the cannon of Waterloo.

On a day in October in 1831, a nine-year-old boy ran frightened away from the edge of a crowd that blocked the door of the blacksmith shop of a village in the mountains of eastern France. Above the awed excited whispers of the people at the door this boy had heard the crackling "s-s-s-s-z" of a white hot iron on human flesh, and this terrifying sizzling had been followed by a groan of pain. The victim was the farmer Nicole. He had just been mangled by a mad wolf that charged howling, jaws dripping poison foam, through the streets of the village. The boy who ran away was Louis Pasteur, son of a tanner of Arbois and great-grandson of a serf of the Count of Udressier.

Days and weeks passed and eight victims of the mad wolf died in the choking throat-parched agonies of hydrophobia. Their screams rang in the ears of this timid—some called him stupid—boy; and the iron that had seared the farmer's wound burned a deep scar in his memory.

"What makes a wolf or a dog mad, father—why do people die when mad dogs bite them?" asked Louis. His father the tanner was an old sergeant of the armies of Napoleon. He had seen ten thousand men die from bullets, but he had no notion of why people die from disease. "Perhaps a devil got into the wolf, and if God wills you are to die, you will die, there is no help for it," you can hear the pious tanner answer. That answer was as good as any answer from the wisest scientist or the most expensive doctor in the world. In 1831 no one knew what caused people to die from mad dog bites—the cause of all disease was completely unknown and mysterious.

I am not going to try to make believe that this terrible event made the nine-year-old Louis Pasteur determine to find out the cause and cure of hydrophobia some day—that would be very romantic—but it wouldn't be true. It is true though that he was more scared by it, haunted by it for a longer time, brooded over it more, that he smelled the burned flesh and heard the screams a hundred times more vividly than an ordinary boy would—in short, he was of the stuff of which artists are made; and it was this stuff in him, as much as his science, that helped him to drag microbes out of that obscurity into which they had passed once more, after the gorgeous Spallanzani died. Indeed, for the first twenty years of his life he showed no signs at all of becoming a great searcher. This Louis Pasteur was only a plodding, careful boy whom nobody noticed particularly. He spent his playtime painting pictures of the river that ran hy the tannery, and his sisters posed for him until their necks grew stiff and their backs ached grievously; he painted curiously harsh unflattering pictures of his mother—they didn't make her look pretty, but they looked like his mother. . . .

Meanwhile it seemed perfectly certain that the little animals were going to be put permanently on the shelf along with the dodo and other forgotten beasts. The Swede Linnæus, most enthusiastic pigeonholer, who toiled at putting all living things in a neat vast card catalogue, threw up his hands at the very idea of studying the wee beasts. "They are too small, too confused, no one will ever know anything exact about them, we will simply put them in the class of Chaos!" said Linnæus. They were only defended by the famous round-faced German Ehrenberg who had immense quarrels—in moments when he wasn't crossing oceans or receiving medals—futile quarrels about whether the little animals had stomachs, strange arguments about whether they were really complete little animals or only parts of larger animals; or whether perchance they might be little vegetables instead of little animals.

Pasteur kept plugging at his books though, and it was while he was still at the little college of Arbois that the first of his masterful traits began to stick out—traits good and bad, that made him one of the strangest mixtures of contradictions that ever lived. He was the youngest boy at the college, but he wanted to be a monitor; he had a fiery ambition to teach other boys, particularly to run other boys. He became a monitor. Before he was twenty he had become a kind of assistant teacher in the college of Bezançon, and here he worked like the devil and insisted that everybody else work as hard as he worked himself; he preached in long inspirational letters to his poor sisters—who, God bless them, were already trying their best—

"To will is a great thing, dear sisters," he wrote, "for Action and Work usually follow Will, and almost always Work is accompanied by Success. These three things, Work, Will, Success, fill human existence. Will opens the door to success both brilliant and happy; Work passes these doors, and at the end of the journey Success comes to crown one's efforts."

When he was seventy his sermons had lost their capital letters, but they were exactly the same kind of simple earnest sermons.

His father sent him up to Paris to the Normal School and there he resolved to do great things, but he was carried away by a homesickness for the smell of the tannery yard and he came back to Arbois abandoning his high ambition. . . . In another year he was back at the same school in Paris and this time he stuck at it; and then one day he passed in a tear-stained trance out of the lecture room of the chemist Dumas. "What a science is chemistry," he muttered, "and how marvelous is the popularity and glory of Dumas." He knew then that he was going to be a great chemist too; the misty gray streets of the Latin Quarter dissolved into a confused and frivolous world that chemistry alone could save. He had left off his painting but he was still the artist.

Presently he began to make his first stumbling independent researches with stinking bottles and rows of tubes filled with gorgeous colored fluids. His good friend Chappuis, a mere student of philosophy, had to listen for hours to Pasteur's lectures on the crystals of tartaric acid, and Pasteur told Chappuis: "It is sad that you are not a chemist too." He would have made all students chemists just as forty years later he tried to turn all doctors into microbe hunters.

Just then, as Pasteur was bending his snub nose and broad forehead over confused piles of crystals, the sub-visible living microbes were beginning to come back into serious notice, they were beginning to be thought of as important serious fellow creatures, just as useful as horses or elephants, by two lonely searchers, one in France and one in Germany. A modest but original Frenchman, Cagniard de la Tour, in 1837 poked round in beer vats of breweries. He dredged up a few foamy drops from such a vat and looked at them through a microscope and noticed that the tiny globules of the yeasts he found in them sprouted buds from their sides, buds like seeds sprouting. "They are alive then, these yeasts, they multiply like other creatures," he cried. His further searchings made him see that no brew of hops and barley ever changed into beer without the presence of the yeasts, living growing yeasts. "It must be their life that changes barley into alcohol," he meditated, and he wrote a short clear paper about it. The world refused to get excited about this fine work of the wee yeasts—Cagniard was no propagandist, he had no press agent to offset his own modesty.

In the same year in Germany Doctor Schwann published a short paper in long sentences, and these muddy phrases told a bored public the exciting news that meat only becomes putrid when sub-visible animals get into it. "Boil meat thoroughly and put it in a clean bottle and lead air into it that has passed through red-hot pipes—the meat will remain perfectly fresh for months. But in a day or two after you remove the stopper and let in ordinary air, with its little animals, the meat will begin to smell dreadfully; it will teem with wriggling, cavorting creatures a thousand times smaller than a pinhead—it is these beasts that make meat go bad."

How Leeuwenhoek would have opened his large eyes at this! Spallanzani would have dismissed his congregation and rushed from his masses to his laboratory; but Europe hardly looked up from its newspapers, and young Pasteur was getting ready to make his own first great chemical discovery.

When he was twenty-six years old he made it. After long peerings at heaps of tiny crystals he discovered that there are four distinct kinds of tartaric acid instead of two; that there are a variety of strange compounds in nature that are exactly alike—excepting that they are mirror-images of each other. When he stretched his arms and straightened up his lame back and realized what he had done, he rushed out of his dirty dark little laboratory into the hall, threw his arms around a young physics assistant—he hardly knew him—and took him out under the thick shade of the Gardens of the Luxembourg. There he poured mouthfuls of triumphant explanation at him—he must tell some one. He wanted to tell the world!

II

In a month he was praised by gray-haired chemists and became the companion of learned men three times his age. He was made professor at Strasbourg and in the off moments of researches he determined to marry the daughter of the dean. He didn't know if she cared for him but he sat down and wrote her a letter that he knew must make her love him:

"There is nothing in me to attract a young girl's fancy," he wrote, "but my recollections tell me that those who have known me very well have loved me very much."

So she married him and became one of the most famous and long-suffering and in many ways one of the happiest wives in history—and this story will have more to tell about her.

Now the head of a house, Pasteur threw himself more furiously into his work; forgetting the duties and chivalries of a bridegroom, he turned his nights into days. "I am on the verge of mysteries," he wrote, "and the veil is getting thinner and thinner. The nights seem to me too long. I am often scolded by Madame Pasteur, but I tell her I shall lead her to fame." He continued his work on crystals; he ran into blind alleys, he did strange and foolish and impossible experiments, the kind a crazy man might devise—and the kind that turn a crazy man into a genius when they come off. He tried to change the chemistry of living things by putting them between huge magnets. He devised weird clockworks that swung plants back and forward, hoping so to change the mysterious molecules that formed these plants into mirror images of themselves. . . . He tried to imitate God: he tried to change species!

Madame Pasteur waited up nights for him and marveled at him and believed in him, and she wrote to his father: “You know that the experiments he is undertaking this year will give us, if they succeed, a Newton or a Galileo!" It is not clear whether good Madame Pasteur formed this so high opinion of her young husband by herself. . . . At any rate, truth, that will o' the wisp, failed him this time—his experiments didn't come off.

Then Pasteur was made Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Sciences in Lille and there he settled down in the Street of the Flowers, and it was here that he ran, or rather stumbled for the first time, upon microbes; it was in this good solid town of distillers and sugar-beet raisers and farm implement dealers that he began his great campaign, part science, part drama and romance, part religion and politics, to put microbes on the map. It was from this not too interesting middle sized city—never noted for learning—that he splashed up a great wave of excitement about microbes that rocked the boat of science for thirty years. He showed the world how important microbes were to it, and in doing this he made enemies and worshipers; his name filled the front pages of newspapers and he received challenges to duels; the public made vast jokes about his precious microbes while his discoveries were saving the lives of countless women in childbirth. In short it was here he hopped off in his flight to immortality.

When he left Strasbourg truth was tricking him and he was confused. He came to Lille and fairly stumbled on to the road to fame—by offering help to a beet-sugar distiller.

When Pasteur settled in Lille he was told by the authorities that highbrow science was all right—

"But what we want, what this enterprising city of Lille wants most of all, professor," you can hear the Committee of business men telling him, "is a close coöperation between your science and our industries. What we want to know is—does science pay? Raise our sugar yield from our beets and give us a bigger alcohol output, and we'll see you and your laboratory are taken care of."

Pasteur listened politely and then proceeded to show them the stuff he was made of. He was much more than a man of science! Think of a committee of business men asking Isaac Newton to show them how his laws of motion were going to help their iron works! That shy thinker would have thrown up his hands and set himself to studying the meaning of the prophecies of the Book of Daniel at once. Faraday would have gone back to his first job as a bookbinder's apprentice. But Pasteur was no shrinking flower. A child of the nineteenth century, he understood that science had to earn its bread and butter, and he started to make himself popular with everybody by giving thrilling lectures to the townspeople on science:

"Where in your families will you find a young man whose curiosity and interest will not immediately be awakened when you put into his hands a potato, and when with that potato he may produce sugar, and with that sugar alcohol, and with that alcohol ether and vinegar?" he shouted enthusiastically one evening to an audience of prosperous manufacturers and their wives. Then one day Mr. Bigo, a distiller of alcohol from sugar beets, came to his laboratory in distress. "We're having trouble with our fermentations, Professor," he complained; "we're losing thousands of francs every day. I wonder if you could come over to the factory and help us out?" said the good Bigo.

Bigo's son was a student in the science course and Pasteur hastened to oblige. He went to the distillery and sniffed at the vats that were sick, that wouldn't make alcohol; he fished up some samples of the grayish slimy mess and put them in bottles to take to his laboratory—and he didn't fail to take some of the beet pulp from the healthy foamy vats where good amounts of alcohol were being made. Pasteur had no idea he could help Bigo, he knew nothing of how sugar ferments into alcohol—indeed, no chemist in the world knew anything about it. He got back to his laboratory, scratched his head, and decided to examine the stuff from the healthy vats first. He put some of this stuff—a drop of it—before his microscope, maybe with an aimless idea of looking for crystals, and he found this drop was full of tiny globules, much smaller than any crystal, and these little globes were yellowish in color, and their insides were full of a swarm of curious dancing specks.

"What can these things be," he muttered. Then suddenly he remembered—

"Of course, I should have known—these are the yeasts you find in all stews that have sugar which is fermenting into alcohol!"

He looked again and saw the wee spheres alone; he saw some in bunches, others in chains, and then to his wonder he came on some with queer buds sprouting from their sides—they looked like sprouts on infinitely tiny seeds.

"Cagniard de la Tour is right. These yeasts are alive. It must be the yeasts that change beet sugar into alcohol!" he cried. "But that doesn't help Mr. Bigo—what on earth can be the matter with the stuff in the sick vats?" He grabbed for the bottle that held the stuff from the sick vat, he sniffed at it, he peered at it with a little magnifying glass, he tasted it, he dipped little strips of blue paper in it and watched them turn red. . . . Then he put a drop from it before his microscope and looked. . . .

"But there are no yeasts in this one; where are the yeasts? There is nothing here but a mass of confused stuff—what is it, what does this mean?" He took the bottle up again and brooded over it with an eye that saw nothing—till at last a different, a strange look of the juice forced its way up into his wool-gathering thoughts. "Here are little gray specks sticking to the walls of the bottle—here are some more floating on the surface—wait! No, there aren't any in the healthy stuff where there are yeasts and alcohol. What can that mean?" he pondered. Then he fished down into the bottle and got a speck, with some trouble, into a drop of pure water; he put it before his microscope. . . .

His moment had come.

No yeast globes here, no, but something different, something strange he had never seen before, great tangled dancing masses of tiny rod-like things, some of them alone, some drifting along like strings of boats, all of them shimmying with a weird incessant vibration. He hardly dared to guess at their size—they were much smaller than the yeasts—they were only one-twenty-five-thousandth of an inch long!

That night he tossed and didn't sleep and next morning his stumpy legs hurried him back to the beet factory. His glasses awry on his nearsighted eyes, he leaned over and dredged up other samples from other sick vats—he forgot all about Bigo and thought nothing of helping Bigo; Bigo didn't exist; nothing in the world existed but his sniffing curious self and these dancing strange rods. In every one of the grayish specks he found millions of them. . . . Feverishly at night with Madame Pasteur waiting up for him and at last going to bed without him, he set up apparatus that made his laboratory look like an alchemist's den. He found that the rod-swarming juice from the sick vats always contained the acid of sour milk—and no alcohol. Suddenly a thought flooded through his brain: "Those little rods in the juice of the sick vats are alive, and it is they that make the acid of sour milk—the rods fight with the yeasts perhaps, and get the upper hand. They are the ferment of the sour-milk-acid, just as the yeasts must be the ferment of the alcohol!" He rushed up to tell the patient Madame Pasteur about it, the only half-understanding Madame Pasteur who knew nothing of fermentations, the Madame Pasteur who helped him so by believing always in his wild enthusiasms. . . .

It was only a guess but there was something inside him that whispered to him that it was surely true. There was nothing uncanny about the rightness of his guess; Pasteur made thousands of guesses about the thousand strange events of nature that met his shortsighted peerings. Many of these guesses were wrong—but when he did hit on a right one, how he did test it and prove it and sniff along after it and chase it and throw himself on it and bring it to earth! So it was now, when he was sure he had solved the ten-thousand-year-old mystery of fermentation.

His head buzzed with a hundred confused plans to see if he was really right, but he never neglected the business men and their troubles, or the authorities or the farmers or his students. He turned part of his laboratory into a manure testing station, he hurried to Paris and tried to get himself elected to the Academy of Sciences—and failed—and he took his classes on educational trips to breweries in Valenciennes and foundries in Belgium. In the middle of this he felt sure, one day, that he had a way to prove that the little rods were alive, that in spite of their miserable littleness they did giant's work, the work no giant could do—of changing sugar into lactic acid.

"I can't study these rods that I think are alive in this mixed-up mess of the juice of the beet-pulp from the vats," Pasteur pondered. "I shall have to invent some kind of clear soup for them so that I can see what goes on—I'll have to invent this special food for them and then see if they multiply, if they have young, if a thousand of the small dancing beings appears where there was only one at first." He tried putting some of the grayish specks from the sick vats into pure sugar water. They refused to grow in it. "The rods need a richer food," he meditated, and after many failures he devised a strange soup; he took some dried yeast and boiled it in pure water and strained it so that it was perfectly clear, he added an exact amount of sugar and a little carbonate of chalk to keep the soup from being acid. Then on the point of a fine needle he fished up one of the gray specks from some juice of a sick fermentation. Carefully he sowed this speck in his new clear soup—and put the bottle in an incubating oven—and waited, waited anxious and nervous; it is this business of experiments not coming off at once that is always the curse of microbe hunting.

He waited and signed some vouchers and lectured to students and came back to peer into his incubator at his precious bottle and advised farmers about their crops and fertilizers and bolted absent-minded meals and peered once more at his tubes—and waited. He went to bed without knowing what was happening in his bottle—it is hard to sleep when you do not know such things. . . .

All the next day it was the same, but toward evening when his legs began to be heavy with failure once more, he muttered: "There is no clear broth that will let me see these beastly rods growing—but I'll just look once more—"

He held the bottle up to the solitary gaslight that painted grotesque giant shadows of the apparatus on the laboratory walls. "Sure enough, there's something changing here," he whispered; "there are rows of little bubbles coming up from some of the gray specks I sowed in the bottle yesterday—there are many new gray specks—all of them are sprouting bubbles!" Then he became deaf and dumb and blind to the world of men; he stayed entranced before his little incubator; hours floated by, hours that might have been seconds for him. He took up his bottle caressingly; he shook it gently before the light—little spirals of gray murky cloud curled up from the bottom of the flask and from these spirals came big bubbles of gas. Now he would find out!

He put a drop from the bottle before his microscope. Eureka! The field of the lens swarmed and vibrated with shimmying millions of the tiny rods. "They multiply! They are alive!" he whispered to himself, then shouted: "Yes, I'll be up in a little while!" to Madame Pasteur who had called down begging him to come up for dinner, to come for a little rest. For hours he did not come.

Time and again in the days that followed he did the same experiment, putting a tiny drop from a flask that swarmed with rods into a fresh clear flask of yeast soup that had none at all—and every time the rods appeared in billions and each time they made new quantities of the acid of sour milk. Then Pasteur burst out—he was net a patient man—to tell the world. He told Mr. Bigo it was the little rods that made his fermentations sick: "Keep the little rods out of your vats and you'll always get alcohol, Mr. Bigo." He told his classes about his great discovery that such infinitely tiny beasts could make acid of sour milk from sugar—a thing no mere man had ever done or could do. He wrote the news to his old Professor Dumas and to all his friends and he read papers about it to the Lille Scientific Society and sent a learned treatise to the Academy of Sciences in Paris. It is not clear whether Mr. Bigo found it possible to keep the little rods out of his vats—for they were like bad weeds that get into gardens. But to Pasteur that didn't matter so much. Here was the one important fact:

It is living things, sub-visible living beings, that are the real cause of fermentations!

Innocently he told every one that his discovery was remarkable—he was too much of a child to be modest—and from now on and for years these little ferments filled his sky; he ate and slept and dreamed and loved—after his absent-minded fashion—with his ferments by him. They were his life.

He worked alone for he had no assistant, not even a boy to wash his bottles for him; how then, you will ask, did he find time to cram his days with such a bewildering jumble of events? Partly because he was an energetic man, and partly it was thanks to Madame Pasteur, who in the words of Roux, "loved him even to the point of understanding his work." On those evenings when she wasn't waiting up lonely for him—when she had finished putting to bed those children whose absent-minded father he was—this brave lady sat primly on a straight-backed chair at a little table and wrote scientific papers at his dictation. Again, while he was below brooding over his tubes and bottles she would translate the cramped scrawls of his notebooks into a clear beautiful handwriting. Pasteur was her life and since Pasteur thought only of work her own life melted more and more into his work. . . .

III

Then one day in the midst of all this—they were just nicely settled in Lille—he came to her and said: "We are going to Paris, I have just been made Administrator and Director of Scientific Studies in the Normal School. This is my great chance."

They moved there, and Pasteur found there was absolutely no place for him to work in; there were a few dirty laboratories for the students but none for the professors; what was worse, the Minister of Instruction told him there was not one cent in the budget for those bottles and ovens and microscopes without which he could not live. But Pasteur snooped round in every cranny of the dirty old building and at last climbed tricky stairs to a tiny room where rats played, to an attic under the roof. He chased the rats out and proclaimed this den his laboratory; he got money—in some mysterious way that is still not clear—for his microscopes and tubes and flasks. The world must know how important ferments are in its life. The world soon knew!

His experiment with the little rods that made the acid of sour milk convinced him—why, no one can tell—that other kinds of small beings did a thousand other gigantic and useful and perhaps dangerous things in the world. "It is those yeasts that my microscope showed me in the healthy beet vats, it is those yeasts that turn sugar into alcohol—it is undoubtedly yeasts that make beer from barley and it is certainly yeasts that ferment grapes into wine—I haven't proved it yet, but I know it." Energetically he wiped his fogged spectacles and cheerfully he climbed to his attic. Experiments would tell him; he must make experiments; he must prove to himself he was right—more especially he must prove to the world he was right. But the world of science was against him.

Liebig, the great German, the prince of chemists, the pope of chemistry, was opposed to his idea. "So Liebig says yeasts have nothing to do with the turning of sugar into alcohol—so he claims that you have to have albumen there, and that it is just the albumen breaking down that carries the sugar along down with it, into alcohol." He would show this Liebig! Then a trick to beat Liebig flashed into his head, a crafty trick, a simple clear experiment that would smash Liebig and all other pooh-bahs of chemistry who scorned the important work that his precious microscopic creatures might do.

"What I have to do is to grow yeasts in a soup that has no albumen in it at all. If yeasts will turn sugar into alcohol in such a soup—then Liebig and his theories are finished." Defiance was in every fiber of him. This business was turning from an affair of cold science into a purely personal matter. But it was one thing to have this bright idea and quite another to find an albumenless food for yeasts—yeasts were squeamish in their tastes, confound them—and he fussed around his drafty attic and was for weeks an exasperated, a very grumpy Pasteur. Until one morning a happy accident cleared the road for him.

He had by chance put some salt of ammonia into an albumen soup in which he grew the yeasts for his experiments. "What's this," he meditated. "The ammonia salt keeps disappearing as my yeasts bud and multiply. What does this mean?" He thought, he fumbled— "Wait! The yeasts use up the ammonia salt, they will grow without the albumen!" slammed shut the door of his attic room, he must be alone while he worked—he loved to be alone as he worked just as he greatly enjoyed spouting his glorious results to worshipful, brilliant audiences. He took clean flasks and poured distilled water into them and carefully weighed out pure sugar and slid it into this water and then put in his ammonia salt—it was the tartrate of ammonia that he used. He reached for a bottle that swarmed with young budding yeasts; with care he fished out a yellowish flake of them and dropped it into his new albumen less soup. He put the bottle in his incubating oven. Would they grow?

That night he turned over and over in his bed. He whispered his hopes and fears to Madame Pasteur—she couldn't advise him but she comforted him. She understood everything but couldn't explain away his worries. She was his perfect assistant. . . .

He was back in his attic next morning not knowing how he had got up the stairs, not remembering his breakfast—he might have floated from his bed directly to the rickety dusty incubator that held his flask—that fatal flask. He opened the bottle and put a tiny cloudy drop from it between two thin bits of glass and slid the specimen under the lens of his microscope—and knew the world was his.

"Here they are," he cried, "lovely budding growing young yeasts, hundreds of thousands of them—yes, and here are some of the old ones, the parent yeasts I sowed in the bottle yesterday." He wanted to rush out and tell some one, but he held himself—he must find out something more—he got some of the soup from the fatal bottle into a retort, to find out whether his budding beings had made alcohol. "Liebig is wrong—albumen isn’t necessary—it is yeasts, the growth of yeasts that ferments sugar." And he watched trickling tears of alcohol run down the neck of the retort. He spent the next weeks in doing the experiment over and over, to be sure that the yeasts would keep on living, to be certain that they would keep on making alcohol. He transferred them monotonously, from one bottle to another—he put them through countless flasks of this same simple soup of ammonia salt and sugar in water and always the yeasts budded lustily and filled the bottles with a foamy collar of carbonic acid gas. Always they made alcohol! This checking-up of his discoveries was dull work. There was not the excitement, the sleepless waiting for a result he hoped for passionately or feared terribly would not come.

His new fact was old stuff by now but still he kept on, he cared for his yeasts like some tender father, he fed them and loved them and was proud of their miraculous work of turning great quantities of sugar into alcohol. He ruined his health watching them and he violated sacred customs of all good middle-class Frenchmen. He writes of how he sat down before his lens at seven in the evening—and this is the dinner hour of France!—he sat down to watch and see if he could spy on his yeasts in the act of budding. "And from that time," he writes, "I did not take my eye from the microscope." It was half past nine before he was satisfied that he had seen them bud. He made vast crazy tests that lasted from June until September to find out how long yeasts would keep at their work of turning sugar into alcohol, and at the end he cried: "Give your yeasts enough sugar, and they will not stop working for three months, or even more!"

Then for a moment the searcher in him changed into a showman, an exhibitor of stupendous surprises, a missionary in the cause of microbes. The world must know and the people of the world must gasp at this astounding news that millions of gallons of wine in France and boundless oceans of beer in Germany are not made by men at all but by incessantly toiling armies of creatures ten-billion times smaller than a wee baby!

He read papers about this and gave speeches and threw his proofs insolently at the great Liebig's head—and in a little while a storm was up in the little Republic of Science on the left bank of the Seine in Paris. His old Professors beamed pride on him and the Academy of Sciences, which had refused to elect him a member, now gave him the Prize of Physiology, and the magnificent Claude Bernard—whom Frenchmen called Physiology itself—praised him in stately sentences. The next night, Dumas, his old professor—whose brilliant lectures had made him cry when he was a green boy in Paris—threw bouquets at Pasteur in a public speech that would have made another man than Pasteur bow his head and blush and protest. Pasteur did not blush—he was perfectly sure that Dumas was right. Instead he sat down proudly and wrote to his father:

"Mr. Dumas, after praising the so great penetration I had given proof of . . . added: The Academy, sir, rewarded you a few days ago for other profound researches; your audience this evening will applaud you as one of the most distinguished professors we possess. All that I have underlined was said in these very words by Mr. Dumas, and was followed by great applause."

It is only natural that in the midst of this hurrahing there was some quiet hissing. Opponents began to rise on all sides. Pasteur made these enemies not entirely because his discoveries stepped on the toes of old theories and beliefs. No, his bristling curious impudent air of challenge got him enemies. He had a way of putting "am-I-not-clever-to-have-found-this-and-aren't-all-of-you-fools-not-to-believe-it-at-once" between the lines of all of his writings and speeches. He loved to fight with words, he had a cocky eagerness to get into an argument with every one about anything. He would have sputtered indignantly at an innocently intended comment on his grammar or his punctuation. Look at portraits of him taken at this time—it was 1860—read his researches, and you will find a fighting sureness of his perpetual rightness in every hair of his eyebrow and even in the technical terms and chemical formulas of his famous scientific papers.

Many people objected to this scornful cockiness—but some good men of science had better reasons for disagreeing with him—his experiments were brilliant, they were startling, but his experiments stopped short of being completely proved. They had loopholes. Every now and then when he set out confidently with some of his gray specks of ferment to make the acid of sour milk, he would find to his disgust a nasty smell of rancid butter wafting up from his bottles. There would be no little rods in the flask—alas—and none of the sour-milk-acid that he had set out to get. These occasional failures, the absence of sure-fire in these tests gave ammunition to his enemies and brought sleepless nights to Pasteur. But not for long! It is not the least strange thing about him that it didn't seem to matter to him that he never quite solved this confusing going wrong of his fermentations; he was a cunning man—instead of butting his head against the wall of this problem, he slipped around it and turned it to his great fame and advantage.

Why this annoying rancid butter smell—why sometimes no sour-milk-acid? One morning, in one of his bottles that had gone bad, he noticed another kind of wee beasts swimming around among a few of the discouraged dancing rods which should have been there in great swarms.

"What are these beasts? They're much bigger than the rods—they don't merely quiver and vibrate—they actually swim around like fish; they must be little animals."

He watched them peevishly, he had an instinct they had no business there. There were processions of them hooked together like barges on the River Seine, strings of clumsy barges that snaked along. Then there were lonely ones that would perform a stately twirl now and again; sometimes they would make a pirouette and balance—the next moment they would shiver at one end in a curious kind of shimmy. It was all very interesting, these various pretty cavortings of these new beasts. But they had no business there! He tried a hundred ways to keep them out, ways that would seem very clumsy to us now, but just as he thought he had cleaned them out of all his bottles, back they popped. Then one day it flashed over him that every time that his bottles of soup swarmed with this gently moving larger sort of animal, these same bottles of soup had the strong nasty smell of rancid butter.

So he proved, after a fashion, that this new kind of beast was another kind of ferment, a ferment that made the rancid-butter-acid from sugar; but he didn't nail down his proof, because he couldn't be sure, absolutely, that there was one kind and only one kind of beast present in his bottles. While he was a little confused and uncertain about this, he turned his troubles once more to his advantage. He was peering, one day, at the rancid butter microbes swarming before his microscope. "There's something new here—in the middle of the drop they are lively, going every which way." Gently, precisely, a little aimlessly, he moved the specimen so that the edge of the drop was under his lens. . . . "But here at the edge they're not moving, they're lying round stiff as pokers." It was so with every specimen he looked at. "Air kills them," he cried, and was sure he had made a great discovery. A little while afterward he told the Academy proudly that he had not only discovered a new ferment, a wee animal that had a curious trick of making stale-butter-acid from sugar, but besides this he had discovered that these animals could live and play and move and do their work without any air whatever. Air even killed them! "And this," he cried, "is the first example of little animals living without air!"

Unfortunately it was the third example. Two hundred years before old Leeuwenhoek had seen the same thing. A hundred years later Spallanzani had been amazed to find that microscopic beasts could live without breathing.

Very probably Pasteur didn't know about these discoveries of the old trail blazers—I am sure he was not trying to steal their stuff—but as he went up in his excited climb toward glory and toward always increasing crowds of new discoveries, he regarded less and less what had been done before him and what went on around him. He re-discovered the curious fact that microbes make meat go bad. He failed to give the first discoverer, Schwann, proper credit for it!

But this strange neglect to give credit for the good work of others must not be posted too strongly against him in the Book of St. Peter, because you can see his fine imagination, that poet's thought of his, making its first attempts at showing that microbes are the real murderers of the human race. He dreams in this paper that just as there is putrid meat, so there are putrid diseases. He tells how he suffered in this work with meat gone bad; he tells about the bad smells—and how he hated bad smells!—that filled his little laboratory during these researches: "My researches on the fermentations have led me naturally toward these studies to which I have resolved to devote myself without too much thought of their danger or of the disgust which they inspire in me," and then he told the Academy of the hard job that awaited him; he explained to them why he must not shrink from it, by making a graceful quotation from the great Lavoisier: "Public usefulness and the interests of humanity ennoble the most disgusting work and only allow enlightened men to see the zeal which is needed to overcome obstacles."

IV

So he prepared the stage for his dangerous experiments—years before he entered on them. He prepared a public stage-setting. His proposed heroism thrilled the calm men of science that were his audience. As they returned home through the gray streets of the ancient Latin Quarter they could imagine Pasteur bidding them a farewell full of emotion, they could see him marching with set lips—wanting to hold his nose but bravely not doing it—into the midst of stinking pestilences where perilous microbes lay in wait for him. . . . It is so that Pasteur proved himself much more useful than Leeuwenhoek or Spallanzani—he did excellent experiments, and then had a knack of presenting them in a way to heat up the world about them. Grave men of science grew excited. Simple people saw clear visions of the yeasts that made the wine that was their staff of life and they were troubled at nights by thoughts of hovering invisible putrid microbes in the air. . . .

He did curious tests that waited three years to be completed. He took flasks and filled them part way full with milk or urine. He doused them in boiling water and sealed their slender necks shut in a blast flame—then for years he guarded them. At last he opened them, to show that the urine and the milk were perfectly preserved, that the air above the fluid in the bottles still had almost all of its oxygen; no microbes, no destruction of the milk! He allowed germs to grow their silent swarms in other flasks of urine and milk that he had left unboiled, and when he tested these for oxygen he found that the oxygen had been completely used up—the microbes had used it to burn up, to destroy the stuff on which they fed. Then like a great bird Pasteur spread his wings of fancy and soared up to fearsome speculations—he imagined a weird world without microbes, a world whose air had plenty of oxygen, but this oxygen would be of no use, alas, to destroy dead plants and animals, because there were no microbes to do the oxidations. His hearers had nightmare glimpses of vast heaps of carcasses choking deserted lifeless streets—without microbes life would not be possible!

Now Pasteur ran hard up against a question that was bound to pop up and look him in the face sooner or later. It was an old question. Adam had without doubt asked it of God, while he wondered where the ten thousand living beings of the garden of Eden came from. It was the question that had all thinkers by the ears for a hundred centuries, that had given Spallanzani so much exciting fun a hundred years before. It was the simple but absolutely insoluble question: Where do microbes come from?

"How is it," Pasteur's opponents asked him, "how is it that yeasts appear from nowhere every year of every century in every corner of the earth, to turn grape juice into wine? Where do the little animals come from, these little animals that turn milk sour in every can and butter rancid in every jar, from Greenland to Timbuctoo?"

Like Spallanzani, Pasteur could not believe that the microbes rose from the dead stuff of the milk or butter. Surely microbes have to have parents! He was, you see, a good Catholic. It is true that he lived among the brainy skeptics on the left bank of the Seine in Paris, where God is as popular as a Soviet would be in Wall Street, but the doubts of his colleagues didn't touch Pasteur. It was beginning to be the fashion of the doubters to believe in Evolution: the majestic poem that tells of life, starting as a formless stuff stirring in a steamy ooze of a million years ago, unfolding through a stately procession of living beings until it gets to monkeys and at last— triumphantly—to men. There doesn't have to be a God to start that parade or to run it—it just happened, said the new philosophers with an air of science.

But Pasteur answered: "My philosophy is of the heart and not of the mind, and I give myself up, for instance, to those feelings about eternity that come naturally at the bedside of a cherished child drawing its last breath. At those supreme moments there is something in the depths of our souls which tells us that the world may be more than a mere combination of events due to a machine-like equilibrium brought out of the chaos of the elements simply through the gradual action of the forces of matter." He was always a good Catholic.

Then Pasteur dropped philosophy and set to work. He believed that his yeasts and rods and little animals came from the air—he imagined an air full of these invisible things. Other microbe hunters had shown there were germs in the air, but Pasteur made elaborate machines to prove it all over again. He poked gun cotton into little glass tubes, put a suction pump on one end of them and stuck the other end out of the window, sucked half the air of the garden through the cotton—and then gravely tried to count the number of living beings in this cotton. He invented clumsy machines for getting these microbe-loaded bits of cotton into yeast soup, to see whether the microbes would grow. He did the good old experiment of Spallanzani over; he got himself a round bottle and put some yeast soup in it, and sealed off the neck of the bottle in the stuttering blast lamp flame, then boiled the soup for a few minutes—and no microbes grew in this bottle.

"But you have heated the air in your flask when you boiled the yeast soup—what yeast soup needs to generate little animals is natural air—you can't put yeast soup together with natural unheated air without its giving rise to yeasts or molds or torulas or vibrions or animalcules!" cried the believers in spontaneous generation, the evolutionists, the doubting botanists, cried all Godless men from their libraries and their armchairs. They shouted, but made no experiments.

Pasteur, in a muddle, tried to invent ways of getting unheated air into a boiled yeast soup—and yet keep it from swarming with living sub-visible creatures. He fumbled at getting a way to do this; he muddled—keeping all the time a brave face toward the princes and professors and publicists that were now beginning to swarm to watch his miracles. The authorities had promoted him from his rat-infested attic to a little building of four or five two-by-four rooms at the gate of the Normal School. It would not be considered good enough to house the guinea-pigs of the great Institutes of to-day, but it was here that Pasteur set out on his famous adventure to prove that there was nothing to the notion that microbes could arise without parents. It was an adventure that was part good experiment, part unseemly scuffle—a scuffle that threatened at certain hilariously vulgar moments to be settled by a fist fight. He messed around, I say, and his apparatus kept getting more and more complicated, and his experiments kept getting easier to object to and less clear, he began to replace his customary easy experiments that convinced with sledge-hammer force, by long drools of words. He was stuck.

Then one day old Professor Balard walked into his workroom. Balard had started life as a druggist; he had been an owlish original druggist who had amazed the scientific world by making the discovery of the element bromine, not in a fine laboratory, but on the prescription counter in the back room of a drugstore. This had got him fame and his job of professor of chemistry in Paris. Balard was not ambitious; he had no yearning to make all the discoveries in the world—discovering bromine was enough for one man's lifetime—but Balard did like to nose around to watch what went on in other laboratories.

"You say you're stuck, you say you do not see how to get air and boiled yeast soup together without getting living creatures into the yeast soup, my friend?" you can hear the lazy Balard asking the then confused Pasteur. "Look here, you and I both believe there is no such thing as microbes rising in a yeast soup by themselves—we both believe they fall in or creep in with the dust of the air, is it not so?"

"Yes," answered Pasteur, "but———"

"Wait a minute!" interrupted Balard. "Why don't you just try the trick of putting some yeast soup in a bottle, boiling it, then fixing the opening so the dust can't fall in. At the same time the air can get in all it wants to."

"But how?" asked Pasteur.

"Easy," replied the now forgotten Balard. "Take one of your round flasks, put the yeast soup into it, then soften the glass of the flask neck in your blast lamp—and draw the neck out and downward into a thin little tube—turn this little tube down the way a swan bends his neck when he's picking something out of the water. Then just leave the end of the tube open. It’s like this———" and Balard sketched a diagram:

Pasteur looked, then suddenly saw the magnificent ingeniousness of this little experiment. "Why, then microbes can't fall into the flask, because the dust they stick to can't very well fall upward—marvelous! I see it now!"

"Exactly," smiled Balard. "Try it and find out if it works—see you later," and he left to continue his genial round of the laboratories.

Pasteur had bottle washers and assistants now, and he ordered them to hurry and prepare the flasks. In a moment the laboratory was buzzing with the stuttering ear-shattering b-r-r-r-r-r of the enameler's lamps; he fell to work savagely. He took flasks and put yeast soup into them and then melted their necks and drew them out and curved them downward—into swan's necks and pigtails and Chinaman's cues and a half-dozen fantastic shapes. Next he boiled the soup in them—that drove out all the air—but as the flasks cooled down new air came in—unheated air, perfectly clean air.

The flasks ready, Pasteur crawled on his hands and knees, back and forth with a comical dignity on his hands and knees, carrying one flask at a time, through a low cubby hole under the stairs to his incubating oven. Next morning he was first at the laboratory, and in a jiffy, battered notebook in his hand, if you had been there you would have seen his rear elevation disappearing underneath the stairway. Like a beagle to its rabbit Pasteur was drawn to this oven with its swan neck flasks. Family, love, breakfast, and the rest of a silly world no longer existed for him.

Had you still been there a half hour later, you would have seen him come crawling out, his eyes shining through his fogged glasses. He had a right to be happy, for every one of the long twisty necked bottles in which the yeast soup had been boiled was perfectly clear—there was not a living creature in them. The next day they remained the same and the next. There was no doubt now that Balard's scheme had worked. There was no doubt that spontaneous generation was nonsense. "What a fine experiment is this experiment of mine—this proves that you can leave any kind of soup, after you’ve boiled it, you can leave it open to the ordinary air, and nothing will grow in it—so long as the air gets into it through a narrow twisty tube."

Balard came back and smiled as Pasteur poured the news of the experiment over him. "I thought it would work—you see, when the air comes back in, as the flask cools, the dusts and their germs start in through the narrow neck—but they get caught on the moist walls of the little tube."

"Yes, but how can we prove that?" puzzled Pasteur.

"Just take one of those flasks that has been in your oven all these days, a flask where no living things have appeared, and shake that flask so that the soup sloshes over and back and forth into the swan's neck part of it. Put it back in the oven, and next morning the soup will be cloudy with thick swarms of little beasts—children of the ones that were caught in the neck."

Pasteur tried it, and it was so! A little later at a brilliant meeting where the brains and wit and art of Paris fought to get in, Pasteur told of his swan neck flask experiment in rapturous words. "Never will the doctrine of Spontaneous Generation recover from the mortal blow that this simple experiment has dealt it," he shouted. If Balard was there you may be sure he applauded as enthusiastically as the rest. A rare soul was Balard.

Then Pasteur invented an experiment that was—so far as one can tell from a careful search through the records—really his own. It was a grand experiment, a semi-public experiment, an experiment that meant rushing across France in trains, it was a test in which he had to slither around on glaciers. Once more his laboratory became a shambles of cluttered flasks and hurrying assistants and tinkling glassware and sputtering, bubbling pots of yeast soup. Pasteur and his enthusiastic slaves—they were more like fanatic monks than slaves—were getting ready hundreds of round bellied bottles. They filled each one of them part full of yeast soup and then, during many hours that shot by like moments—such was their excitement—they doused each bottle for a few minutes in boiling water. And while the soup was boiling they drew the flask necks out in a spitting blue flame until they were sealed shut. Each one of this regiment of bottles held boiled yeast soup—and a vacuum.

Armed with these dozens of flasks, and fussing about them, Pasteur started on his travels. He went down first into the dank cellars of the Observatory of Paris, that famous Observatory where worked the great Le Verrier, who had done the proud feat of prophesying the existence of the planet Neptune. "Here the air is so still, so calm," said Pasteur to his boys, "that there will be hardly any dust in it, and almost no microbes." Then, holding the flasks far away from their bodies, using forceps that had been heated red hot in a flame, they cracked the necks of ten of the flasks in succession; as the neck came off each one, there was a hissing "s-s-s-s" of air rushing in. At once they sealed the bottles shut again in the flickering flame of an alcohol lamp. They did the same stunt in the yard of the observatory with another ten bottles, then hurried back to the little laboratory to crawl under the stairs to put the bottles in the incubating oven.

A few days later Pasteur might have been seen squatting before his oven, handling his rows of flasks lovingly, laughing his triumph with one of those extremely rare laughs of his—he only laughed when he found out he was right. He put down tiny scrawls in his notebook, and then crawled out of his cubby-hole to tell his assistants: "Nine out of ten of the bottles we opened in the cellar of the Observatory are perfectly clear—not a single germ got into them. All the bottles we opened in the yard are cloudy—swarming with living creatures. It's the air that sucks them into the yeast soup—it’s the dust of the air they come in with!"

He gathered up the rest of the bottles and hurried to the train—it was the time of the summer vacation when other professors were resting—and he went to his old home in the Jura mountains and climbed the hill of Poupet and opened twenty bottles there. He went to Switzerland and perilously let the air hiss into twenty flasks on the slopes of Mont Blanc; and found, as he had hoped, that the higher he went, the fewer were the flasks of yeast soup that became cloudy with swarms of microbes. "That is as it ought to be," he cried, "the higher and clearer the air, the less dust—and the fewer the microbes that always stick to particles of the dust." He came back proudly to Paris and told the Academy—with proofs that would astonish everybody!—that it was now sure that air alone could never cause living things to rise in yeast soup. "Here are germs, right beside them there are none, a little further on there are different ones . . . and here where the air is perfectly calm there are none at all," he cried. Then once more he set a new stage for possible magnificent exploits: "I would have liked to have gone up in a balloon to open my bottles still higher up!" But he didn't go up in that

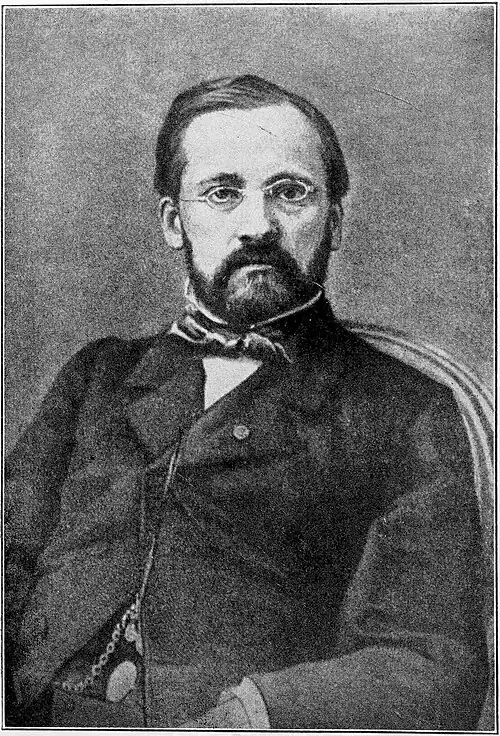

PASTEUR AT FORTY-FIVE

balloon, for his hearers were already sufficiently astonished. Already they considered him to be more than a man of science; he became for them a composer of epic searchings, a Ulysses of microbe hunters—the first adventurer of that heroic age to which you will soon come in this story.

Many times Pasteur won his arguments by brilliant experiments that simply floored every one, but sometimes his victories were due to the weakness or silliness of his opponents, and again they were the result of—luck. Before a society of chemists Pasteur had insulted the scientific ability of naturalists; he was astonished, he shouted, that naturalists didn't stretch out a hand to the real way of doing science—that is, to experiments. "I am of the persuasion that that would put a new sap into their science," he said. You can imagine how the naturalists liked that kind of talk; particularly Mr. Pouchet, director of the Museum of Rouen, did not like it and he was enthusiastically joined in not liking it by Professor Joly and Mr. Musset, famous naturalists of the College of Toulouse. Nothing could convince these enemies of Pasteur that microscopic beasts did not come to life without parents. They were sure there was such a thing as life arising spontaneously; they decided to beat Pasteur on his own ground at his own game.

Like Pasteur they filled up some flasks, but unlike him they used a soup of hay instead of yeast, they made a vacuum in their bottles and hastened to high Maladetta in the Pyrenees, and they kept climbing until they had got up many feet higher than Pasteur had been on Mont Blanc. Here, beaten upon by nasty breezes that howled out of the caverns of the glaciers and sneaked through the thick linings of their coats, they opened their flasks—Mr. Joly almost slid off the edge of the ledge and was only saved from a scientific martyr's death when a guide grabbed him by the coat tail! Out of breath and chilled through and through they staggered back to a little tavern and put their flasks in an improvised incubating oven—and in a few days, to their joy, they found every one of their bottles swarming with little creatures. Pasteur was wrong!

Now the fight was on. Pasteur became publicly sarcastic about the experiments of Pouchet, Joly and Musset; he made criticisms that to-day we know are quibbles. Pouchet came back with the remark that Pasteur "had presented his own flasks as an ultimatum to science to astonish everybody." Pasteur was furious, denounced Pouchet as a liar and bawled for a public apology. It seemed, alas, as if the truth were going to be decided by the spilling of blood, instead of by calm experiment. Then Pouchet and Joly and Musset challenged Pasteur to a public experiment before the Academy of Sciences, and they said that if one single flask would fail to grow microbes after it had been opened for an instant, they would admit they were wrong. The fatal day for the tests dawned at last—what an interesting day it would have been—but at the last moment Pasteur's enemies backed down. Pasteur did his experiments before the Commission—he did them confidently with ironical remarks—and a little while later the Commission announced: "The facts observed by Mr. Pasteur and contested by Messrs. Pouchet, Joly and Musset, are of the most perfect exactitude."

Luckily for Pasteur, but alas for Truth, both sides happened to be right. Pouchet and his friends had used hay instead of yeast soup, and a great Englishman, Tyndall, found out years later that hay holds wee stubborn seeds of microbes that will stand boiling for hours! It was really Tyndall that finally settled this great quarrel; it was Tyndall that proved Pasteur was right.

V

Pasteur was now presented to the Emperor Napoleon III. He told that dreamy gentleman that his whole ambition was to find the microbes that he was sure must be the cause of disease. He was invited to an imperial house party at Compiègne, The guests were commanded to get ready to go hunting, but Pasteur begged to be excused; he had had a dray load of apparatus sent up from Paris—though he was only staying at the palace for a week!—and he impressed their Imperial Majesties enormously by bending over his microscope while everybody else was occupied with frivolous and gay amusements.

The world must know that microbes have got to have parents! At Paris he made a popular speech at the scientific soirée at the Sorbonne, before Alexandre Dumas, the novelist, and the woman genius, George Sand, the Princess Mathilde, and a hundred more smart people. That night he staged a scientific vaudeville that sent his audience home in awe and worry; he showed them lantern slides of a dozen different kinds of germs; mysteriously he darkened the hall and suddenly shot a single bright beam of light through the blackness. "Observe the thousands of dancing specks of dust in the path of this ray," he cried; "the air of this hall is filled with these specks of dust, these thousands of little nothings that you should not despise always, for sometimes they carry disease and death; the typhus, the cholera, the yellow fever and many other pestilences!" This was dreadful news; his audience shuddered, convinced by his sincerity. Of course this news was not strictly true, but Pasteur was no mountebank—he believed it himself! Dust and the microbes of the dust had become his life—he was obsessed with dust. At dinner, even at the smartest houses, he would hold his plates and spoons close up to his nose, peer at them, scour them with his napkin, he was with a vengeance putting microbes on the map. . . .

Every Frenchman from the Emperor down was becoming excited about Pasteur and his microbes. Whisperings of mysterious and marvelous events seeped through the gates of the Normal School. Students, even professors, passed the laboratory a little atremble with awe. One student might be heard remarking to another, as they passed the high gray walls of the Normal School in the Rue d'Ulm: "There is a man working here—his name is Pasteur—who is finding out wonderful things about the machinery of life, he knows even about the origin of life, he is even going to find out, perhaps, what causes disease. . . ." So Pasteur succeeded in getting another year added to the course of scientific studies; new laboratories began to go up; his students shed tears of emotion at the fiery eloquence of his lectures. He talked about microbes causing disease long before he knew anything about whether or not they caused disease—he hadn't yet got his fingers at the throats of mysterious plagues and dreadful deaths, but he knew there were other ways to interest the public, to arouse even such a hardheaded person as the average Frenchman.

"I beg you," he addressed the French people in a passionate pamphlet, "take some interest in those sacred dwellings meaningly called laboratories. Ask that they be multiplied and completed. They are the temples of the future, of riches and comfort." Fifty years ahead of his time as a forward-looking prophet, he held fine austere ideals up to his countrymen while he appealed to their wishes for a somewhat piggish material happiness. A good microbe hunter, he was much more than a mere woolgathering searcher, much more than a mere man of science. . . .

Once more he started out to show all of France how science could save money for her industry; he packed up boxes of glassware and an eager assistant, Duclaux, and bustled off to Arbois, his old home—he hurried off up there to study the diseases of wine—to save the imperiled wine industry. He set up his laboratory in what had been an old café and instead of gas burners he had to be satisfied with an open charcoal brazier that the enthusiastic Duclaux kept glowing with a pair of bellows; from time to time Duclaux would scamper across to the town pump for water; their clumsy apparatus was made by the village carpenter and tinsmith. Pasteur rushed around to his friends of long ago and begged bottles of wine, bitter wine, ropy wine, oily wine; he knew from his old researches that it was yeasts that changed grapejuice into wine—he felt certain that it must be some other wee microscopic being that made wines go bad.

Sure enough! When he turned his lens on to ropy wines he found them swarming with very tiny curious microbes hitched together like strings of beads; he found the bottles of bitter wine infested with another kind of beast and the kegs of turned wine by still another. Then he called the winegrowers and the merchants of the region together and proceeded to show them magic.

"Bring me a half dozen bottles of wine that has gone bad with different sicknesses," he asked them. "Do not tell me what is wrong with them, and I'll tell you what ails them without tasting them." The winegrowers didn’t believe him; among each other they snickered at him as they went to fetch the bottles of sick wine; they laughed at the fantastic machinery in the old café; they took Pasteur for some kind of earnest lunatic. They planned to fool him and brought him bottles of perfectly good wine among the sick ones. Then he set about flabbergasting them! With a slender glass tube he sucked a drop of wine out of a bottle and put it between two little slips of glass before his microscope. The wine raisers nudged each other and winked French winks of humorous common sense, while Pasteur sat hunched over his microscope, and they became more merry as minutes passed. . . .

Suddenly he looked at them and said: "There is nothing the matter with this wine—give it to the taster—let him see if I'm right."

The taster did his tasting, then puckered up his purple nose and admitted that Pasteur was correct; and so it went through a long row of bottles—when Pasteur looked up from his micro- scopes and prophesied: "Bitter wine"—it turned out to be bitter; and when he foretold that the next sample was ropy, the taster acknowledged that ropy was right!

The wine raisers mumbled their thanks and lifted their hats to him as they left. "We don't get the way he does this—but he is a very clever man, very, very clever," they muttered. That is much for a peasant Frenchman to admit. . . .

When they left, Pasteur and Duclaux worked triumphantly in their tumbledown laboratory; they tackled the question of how to keep these microbes out of healthy wines—they found at last that if you heat wine just after it has finished fermenting, even if you heat it gently, way below the point of boiling, the microbes that have no business in the wine will be killed—and the wine will not become sick. That little trick is now known to everybody by the name of pasteurization.

Now that people of the East of France had been shown how to keep their wine from going bad, the people of the middle of France clamored for Pasteur to come and save their vinegar-making industry. So he rushed down to Tours. He had got used to looking for microscopic beings in all kinds of things by now—he no longer groped as he had had to do at first; he approached the vinegar kegs, where wine was turning itself into vinegar, he saw a peculiar-looking scum on the surface of the liquor in the barrels. "That scum has to be there, otherwise we get no vinegar," explained the manufacturers. In a few weeks of swift, sure-fingered investigation that astonished the vinegar-makers and their wives, Pasteur found that the scum on the kegs was nothing more nor less than billions upon billions of microscopic creatures. He took off great sheets of this scum and tested it and weighed it and fussed with it, and at last he told an audience of vinegar-makers and their wives and families that the microbes which change wine to vinegar actually eat up and turn into vinegar ten thousand times their own weight of alcohol in a few days. What gigantic things these infinitely tiny beings can do—think of a man of two hundred pounds chopping two millions of pounds of wood in four days! It was by some such homely comparison as this one that he made microbes part of these humble people's lives, it was so that he made them respect these miserably small creatures; it was by pondering on their fiendish capacity for work that Pasteur himself got used to the idea that there was nothing so strange about a tiny beast, no larger than the microbe of vinegar, getting into an ox or an elephant or a man—and doing him to death. Before he left them he showed the people of Tours how to cultivate and care for those useful wee creatures that so strangely added oxygen to wine to turn it into vinegar—and millions of francs for them.

These successes made Pasteur drunk with confidence in his method of experiment; he began to dream impossible gaudy dreams—of immense discoveries and super-Napoleonic microbe huntings—and he did more than brood alone over these dreams; he put them into speeches and preached them. He became, in a word, a new John the Baptist of the religion of the Germ Theory, but unlike the unlucky Baptist, Pasteur was a forerunner who lived to see at least some of his prophecies come true.

Then for a short time he worked quietly in his laboratory in Paris—there was nothing for him to save just then—until one day in 1865 Fate came to his door and knocked. Fate in the guise of his old professor, Dumas, called on him and asked him to change himself from a man of science into a silkworm doctor. "What's wrong with silkworms? I did not know that they ever had diseases—I know nothing at all about silkworms—what's more, I have never even seen one!" protested Pasteur.

VI

"The silk country of the South is my native country," answered Dumas. "I've just come back from there—it is terrible—I cannot sleep nights for thinking of it, my poor country, my village of Alais. . . . This country that used to be rich, that used to be gay with mulberry trees which my people used to call the Golden Tree—this country is desolate now. The lovely terraces are going to ruin—the people, they are my people, they are starving. . . ." Tears were in his voice.

Anything but a respecter of persons, Pasteur who loved and respected himself above all men, had always kept a touching reverence for Dumas. He must help his sad old professor! But how? It is doubtful at this time if Pasteur could have told a silkworm from an angle worm! Indeed, a little later, when he was first given a cocoon to examine, he held it up to his ear, shook it, and cried: "Why, there is something inside it!" Pasteur hated to go South to try to find out what ailed silkworms, he knew he risked a horrid failure by going and he detested failure above everything. But it is one of the charming things about him that in the midst of all his arrogance, his vulgar sureness of himself, he had kept that boyish love and reverence for his old master—so he said to Dumas: "I am in your hands, I'm at your disposal, do with me as you wish—I will go!"

So he went. He packed up the never complaining Madame Pasteur and the children and a microscope and three energetic and worshiping young assistants and he went into the epidemic that was slaughtering millions of silkworms and ruining the South of France. Knowing less of silkworms and their sicknesses than a babe in swaddling clothes he arrived in Alais; he got there and he learned that a silkworm spins a cocoon round itself and turns into a chrysalid inside the cocoon; he found out that the chrysalid changes into a moth that climbs out and lays eggs—which hatch out the next spring into new broods of young silkworms. The silkworm growers—disgusted at his great ignorance—told him that the disease which was killing their worms was called pébrine, because the sick worms were covered with little black spots that looked like pepper. Pasteur found out that there were a thousand or so theories about the sickness, but that the little pepper spots—and the curious little globules inside the sick worms, wee globules that you could only see with a microscope—were the only facts that were known about it.

Then Pasteur unlimbered his microscope, before he had got his family settled—he was like one of those trout fishing maniacs who starts to cast without thought of securing his canoe safely on the bank—he unlimbered his microscope, I say, and began to peer at the insides of sick worms, and particularly at these wee globules. Quickly he concluded that the globules were a sure sign of the disease. Fifteen days after he had come to Alais he called the Agricultural Committee together and told them: "At the moment of egg-laying put aside each couple of moths, the father and the mother. Let them mate; let the mother lay her eggs—then pin the father and mother moths down onto a little board, slit open their bellies and take out a little of the fatty tissue under their skin; put this under a microscope and look for those tiny globules. If you can't find any, you can be sure the eggs are sound—you can use those eggs for new silkworms in the spring."

The committee looked at the shining microscope. "We farmers can't run a machine like that," they objected. They were suspicious, they didn't believe in this newfangled machine. Then the salesman that was in Pasteur came to the front. "Nonsense!" he answered. "There is an eight-year-old girl in my laboratory who handles this microscope easily and is perfectly able to spot these little globules—these corpuscles— and then you grown men try to tell me you couldn't learn to use a microscope!" So he shamed them. And the committee obediently bought microscopes and tried to follow his directions. Then Pasteur started a hectic life; he was everywhere around the tragic silk country, lecturing, asking innumerable questions, teaching the farmers to use microscopes, rushing back to the laboratory to direct his assistants—he directed them to do complicated experiments that he hadn't time to do, or even watch, himself—and in the evenings he dictated answers to letters and scientific papers and speeches to Madame Pasteur. The next morning he was off again to the neighboring towns, cheering up despairing farmers and haranguing them. . . .

But the next spring his bubble burst, alas. The next spring, when it came time for the worms to climb their mulberry twigs to spin their silk cocoons, there was a horrible disaster. His confident prophecy to the farmers did not come true. These honest people glued their eyes to their microscopes to pick out the healthy moths, so as to get healthy eggs, eggs without the evil globules in them—and these supposed healthy eggs hatched worms, sad to tell, who grew miserably, languid worms who would not eat, strange worms who failed to molt, sick worms who shriveled up and died, lazy worms who hung around at the bottoms of their twigs, not caring whether there was ever another silk stocking on the leg of any fine lady in the world.

Poor Pasteur! He had been so busy trying to save the silkworm industry that he hadn't taken time to find out what really ailed the silkworms. Glory had seduced him into becoming a mere savior—for a moment he forgot that Truth is a will o' the wisp that can only be caught in the net of glory-scorning patient experiment. . . .

Some silkworm raisers laughed despairing laughs at him—others attacked him bitterly; dark days were on him. He worked the harder for them, but he couldn't find bottom. He came on broods of silkworms who fairly galloped up the twigs and proceeded to spin elegant cocoons—then at the microscope he found these beasts swarming with the tiny globules. He discovered other broods that sulked on their branches and melted away with a gassy diarrhœa and died miserably—but in these he could find no globules whatever. He became completely mixed up; he began to doubt whether the globules had anything to do with the disease. Then to make things worse, mice got into the broods of his experimental worms and made cheerful meals on them and poor Duclaux, Maillot and Gernez had to stay up by turns all night to catch the raiding mice; next morning everybody would be just started working when black clouds appeared in the West, and all of them—Madame Pasteur and the children bringing up the rear—had to scurry out to cover up the mulberry trees. In the evenings Pasteur had to settle his tired back in an armchair, to dictate answers to peeved silkworm growers who had lost everything—using his method of sorting eggs.

After a series of such weary months, his instinct to do experiments, this instinct—and the Goddess of Chance—came together to save him. He pondered to himself: "I've at least managed to scrape together a few broods of healthy worms—if I feed these worms mulberry leaves smeared with the discharges of sick worms, will the healthy worms die?" He tried it, and the healthy worms died sure enough, but, confound it! the experiment was a fizzle again—for instead of getting covered with pepper spots and dying slowly in twenty-five days or so, as worms always do of pébrine—the worms of his experiment curled up and passed away in seventy-two hours. He was discouraged, he stopped his experiments; his faithful assistants worried about him—why didn't he try the experiment over?

At last Gernez went off to the north to study the silk worms of Valenciennes, and Pasteur, not clearly knowing the reason why, wrote to him and asked him to do that feeding experiment up there. Gernez had some nice broods of healthy worms. Gernez was sure in his own head—no matter what his chief might think—that the wee globules were really living things, parasites, assassins of the silkworm. He took forty healthy worms and fed them on good healthy mulberry leaves that had never been fed on by sick beasts. These worms proceeded to spin twenty-seven good cocoons and there were no globules in the moths that came from them. He smeared some other leaves with crushed-up sick moths and fed them to some day-old worms—and these worms wasted away to a slow death, they became covered with pepper spots and their bodies swarmed with the sub-visible globules. He took some more leaves with crushed-up sick moths and fed these to some old worms just ready to spin cocoons; the worms lived to spin the cocoons, but the moths that came out of the cocoons were loaded with the globules, and the worms from their eggs came to nothing. Gernez was excited—and he became more excited when still nights at his microscope showed him that the globules increased tremendously as the worms faded to their deaths. . . .

Gernez hurried to Pasteur. "It is solved," he cried, "the little globules are alive—they are parasites!—They are what make the worms sick!"