Microbe Hunters/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

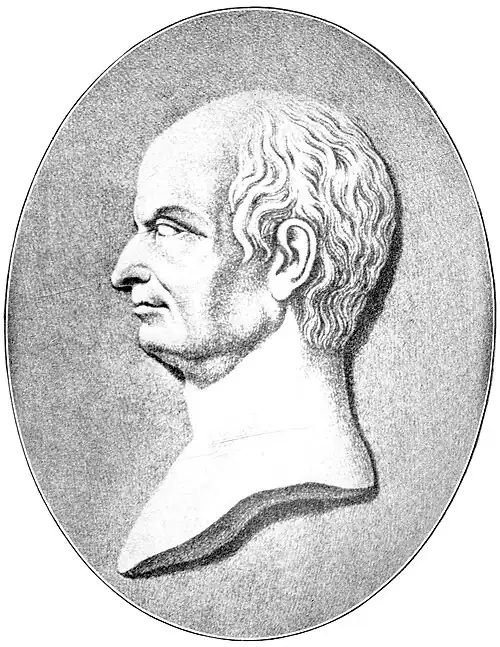

SPALLANZANI

MICROBE MUST HAVE PARENTS!

I

"Leeuwenhoek is dead, it is too bad, it is a loss that cannot be made good. Who now will carry on the study of the little animals?" asked the learned men of the Royal Society in England, asked Réaumur and the brilliant Academy in Paris. Their question did not wait long for an answer, for the janitor of Delft had hardly closed his eyes in 1723 for the long sleep that he had earned so well, when another microbe hunter was born, in 1729 a thousand miles away in Scandiano in northern Italy. This follower of Leeuwenhoek was Lazzaro Spallanzani, a strange boy who lisped verses while he fashioned mudpies; who forgot mudpies to do fumbling childish and cruel experiments with beetles and bugs and flies and worms. Instead of pestering his parents with questions, he examined living things in nature, by pulling legs and wings off them, by trying to stick them back on again. He must find out how things worked; he didn't care so very much what they looked like.

Like Leeuwenhoek, the young Italian had to fight to become a microbe hunter against the wishes of his family. His father was a lawyer and did his best to get Lazzaro interested in long sheets of legal foolscap—but the youngster sneaked away and skipped flat stones over the surface of the water, and wondered why the stones skipped and didn't sink.

In the evenings he was made to sit down before dull lessons, but when his father's back was turned he looked out of the window at the stars that gleamed in the velvet black Italian sky, and next morning lectured about them to his playmates until they called him "The Astrologer."

On holidays he pushed his burly body through the woods near Scandiano, and came wide-eyed upon foaming natural fountains. These made him stop his romping, and caused him to go home sunk in unboyish thought. What caused these fountains? His folks and the priest had told him they had sprung in olden times from the tears of sad, deserted, beautiful girls who were lost in the woods. . . .

Lazzaro was a dutiful son—and a politician of a son—so he didn't argue with his father or the priest. But to himself he said "bunk" to their explanation, and made up his mind to find out, some day, the real why and wherefore of fountains.

Young Spallanzani was just as determined as Leeuwenhoek had been to find out the hidden things of nature, but he set about getting to be a scientist in an entirely different way. He pondered: "My father insists that I study law, does he?" He kept up the pretense of being interested in legal documents—but in every spare moment he boned away: at mathematics and Greek and French and Logic—and during his vacations watched skipping stones and fountains, and dreamed about understanding the violent fireworks of volcanoes. Then craftily he went to the noted scientist, Vallisnieri, and told this great man what he knew. "But you were born for a scientist," said Vallisnieri, "you waste time foolishly, studying lawbooks."

"Ah, master, but my father insists."

Indignantly Vallisnieri went to Spallanzani senior and scolded him for throwing away Lazzaro's talents on the merely useful study of law. 'Your boy," he said, "is going to be a searcher, he will honor Scandiano, and make it famous—he is like Galileo!"

And the shrewd young Spallanzani went to the University at Reggio, with his father's blessing, to take up the career of scientist.

At this time it was much more respectable and safe to be a Scientist than it had been when Leeuwenhoek began his first grinding of lenses. The Grand Inquisition was beginning to pull in its horns. It preferred jerking out the tongues of obscure alleged criminals and burning the bodies of unknown heretics, to persecuting Servetuses and Galileos. The Invisible College no longer met in cellars or darkened rooms, and learned societies all over were now given the generous support of parliaments and kings. It was not only beginning to be permitted to question superstitions, it was becoming fashionable to do it. The thrill and dignity of real research into nature began to elbow its way into secluded studies of philosophers. Voltaire retired for years into the wilds of rural France to master the great discoveries of Newton, and then to popularize them in his country. Science even penetrated into brilliant and witty and immoral drawing-rooms, and society leaders like Madame de Pompadour bent their heads over the forbidden Encyclopedia—to try to understand the art and science of the making of rouge and silk stockings.

Along with this excited interest in everything from the mechanics of the stars to the caperings of little animals, the people of Spallanzani's glittering century began to show an open contempt for religion and dogmas, even the most sacred ones. A hundred years before men had risked their skins to laugh at the preposterous and impossible animals that Aristotle had gravely put into his books on biology. But now, they could openly snicker at the mention of his name and whisper: "Because he's Aristotle it implies that he must be believed e'en though he lies." Still there was plenty of ignorance in the world, and much pseudo-science—even in the Royal Societies and Academies. And Spallanzani, freed from the horror of an endless future of legal wranglings, threw himself with vigor into getting all kinds of knowledge, into testing all kinds" of theories, into disrespecting all kinds of authorities no matter how famous, into association with every kind of person, from fat bishops, officials, and professors to outlandish actors and minstrels.

He was the very opposite of Leeuwenhoek, who so patiently had ground lenses, and looked at everything for twenty years before the learned world knew anything about him. At twenty-five Spallanzani made translations of the ancient poets, and criticized the standard and much admired Italian translation of Homer. He brilliantly studied mathematics with his cousin, Laura Bassi, the famous woman professor of Reggio. He now skipped stones over the water in earnest, and wrote a scientific paper on the mechanics of skipping stones. He became a priest of the Catholic Church, and helped support himself by saying masses.

Despising secretly all authority, he got himself snugly into the good graces of powerful authorities, so that he might work undisturbed. Ordained a priest, supposed to be a blind follower of the faith, he fell savagely to questioning everything, to taking nothing for granted—excepting the existence of God, of some sort of supreme being. At least if he questioned this he kept it—rogue that he was—strictly to himself. Before he was thirty years old he had been made professor at the University of Reggio, talking before enthusiastic classes that listened to him with saucer-eyes. Here he started his first work on the little animals, those weird new little beings that Leeuwenhoek had discovered. He began his experiments on them as they were threatening to return to that misty unknown from which the Dutchman had dredged them up.

The little animals had got themselves involved in a strange question, in a furious fight, and had it not been for that, they might have remained curiosities for centuries, or even have been completely forgotten. This argument, over which dear friends grew to hate each other and about which professors tried to crack the skulls of priests, was briefly this: Can living things arise spontaneously, or does every living thing have to have parents? Did God create every plant and animal in the first six days, and then settle down to be Managing Director of the universe, or does He even now amuse Himself by allowing new animals to spring up in humorous ways?

In Spallanzani's time the popular side was the party that asserted that life could arise spontaneously. The great majority of sensible people believed that many animals did not have to have parents—that they might be the unhappy illegitimate children of a disgusting variety of dirty messes. Here, for example, was a supposedly sure recipe for getting yourself a good swarm of bees. Take a young bullock, kill him with a knock on the head, bury him under the ground in a standing position with his horns sticking out. Leave him there for a month, then saw off his horns—and out will fly your swarm of bees.

II

Even the scientists were on this side of the question. The English naturalist Ross announced learnedly that: "To question that beetles and wasps were generated in cow dung is to question reason, sense, and experience." Even such complicated animals as mice didn't have to have mothers or fathers—if anybody doubted this, let him go to Egypt, and there he would find the fields literally swarming with mice, begot of the mud of the River Nile—to the great calamity of the inhabitants!

Spallanzani heard all of these stories which so many important people were sure were facts, he read many more of them that were still more strange, he watched students get into brawls in excited attempts to prove that mice and bees didn't have to have fathers or mothers. He heard all of these things—and didn't believe them. He was prejudiced. Great advances in science so often start from prejudice, on ideas got not from science but straight out of a scientist's head, on notions that are only the opposite of the prevailing superstitious nonsense of the day. Spallanzani had violent notions about whether life could rise spontaneously; for him it was on the face of things absurd to think that animals—even the wee beasts of Leeuwenhoek—could arise in a haphazard way from any old thing or out of any dirty mess. There must be law and order to their birth, there must be a rime and reason! But how to prove it?

Then one night, in his solitude, he came across a little book, a simple and innocent little book, and this book told him of an entirely new way to tackle the question of how life arises. The fellow who wrote the book didn't argue with words—he just made experiments—and God! thought Spallanzani, how clear are the facts he demonstrates. He stopped being sleepy and forgot the dawn was coming, and read on. . . .

The book told him of the superstition about the generation of maggots and flies, it told of how even the most intelligent men believed that maggots and flies could arise out of putrid meat. Then—and Spallanzani's eyes nearly popped out with wonder, with excitement, as he read of a little experiment that blew up this nonsense, once and for always.

"A great man, this fellow Redi, who wrote this book," thought Spallanzani, as he took off his coat and bent his thick neck toward the light of the candle. 'See how easy he settles it! He takes two jars and puts some meat in each one. He leaves one jar open and then puts a light veil over the other one. He watches—and sees flies go down into the meat in the open pot—and in a little while there are maggots there, and then new flies. He looks at the jar that has the veil over it—and there are no maggots or flies in that one at all. How easy! It is just a matter of the veil keeping the mother flies from getting at the meat. . . . But how clever, because for a thousand years people have been getting out of breath arguing about the question—and not one of them thought of doing this simple experiment that settles it in a moment."

Next morning it was one jump from the inspiring book to tackling this same question, not with flies, but with the microscopic animals. For all the professors were saying just then that though maybe flies had to come from eggs, little sub-visible animals certainly could rise by themselves.

Spallanzani began fumblingly to learn how to grow wee beasts, and how to use a microscope. He cut his hands and broke large expensive flasks. He forgot to clean his lenses and sometimes saw his little animals dimly through his fogged glasses—just as you can faintly make out minnows in the water tiled up by your net. He raved at his blunders; he was not the dogged worker that Leeuwenhoek had been—but. despite his impetuousness he was persistent—he must prove that these yarns about the animalcules were yarns, nothing more. But wait! "If I set out to prove something I am no real scientist—I have to learn to follow where the facts lead me—I have to learn to whip my prejudices. . . ." And he kept on learning to study little animals, and to observe with a patient, if not an unprejudiced eye, and gradually he taught the vanity of his ideas to bow to the hard clearness of his facts.

At this time another priest, named Needham, a devout Catholic who liked to think he could do experiments, was becoming notorious in England and Ireland, claiming that little microscopic animals were generated marvelously in mutton gravy. Needham sent his experiments to the Royal Society, and the learned Fellows deigned to be impressed.

He told them how he had taken a quantity of mutton gravy hot from the fire, and put the gravy in a bottle, and plugged the bottle up tight with a cork, so that no little animals or their eggs could possibly get into the gravy from the air. Next he even went so far as to heat the bottle and its mutton gravy in hot ashes. "Surely," said the good Needham, "this will kill any little animals or their eggs, that might remain in the flask." He put this gravy flask away for a few days, then pulled the cork—and marvel of marvels—when he examined the stuff inside with his lens, he found it swarming with animalcules.

"A momentous discovery, this," cried Needham to the Royal Society, "these little animals can only have come from the juice of the gravy. Here is a real experiment showing that life can come spontaneously from dead stuff!" He told them mutton-gravy wasn't necessary—a soup made from seeds or almonds would do the same trick.

The Royal Society and the whole educated world were excited by Needham's discovery. Here was no Old Wives' tale. Here was hard experimental fact; and the heads of the Society got together and thought about making Needham a Fellow of their remote aristocracy of learning. But away in Italy, Spallanzani was reading the news of Needham's startling creation of little animals from mutton gravy. While he read he knit his brows, and narrowed his dark eyes. At last he snorted: "Animalcules do not arise by themselves from mutton gravy, or almond seeds, or anything else! This fine experiment is a fraud—maybe Needham doesn't know it is—but there's a nigger in the wood pile somewhere. I'm going to find it. . . ."

The devil of prejudice was talking again. Now Spallanzani began to sharpen his razors for his fellow priest—the Italian was a nasty fellow who liked to slaughter ideas of any kind that were contrary to his—he began to whet his knives, I say, for Needham. Then one night, alone in his laboratory, away from the brilliant clamor of his lectures and remote from the gay salons where ladies adored his knowledge, he felt sure he had found the loophole in Needham's experiment. He chewed his quill, he ran his hands through his shaggy hair, "Why have those little animals appeared in that hot gravy, and in those soups made from seeds?" Undoubtedly because Needham didn't heat the bottles long enough, and surely because he didn't plug them tight enough!

Here the searcher in him came forward—he didn't go to his desk to write Needham about it—instead he went to his dusty glass-strewn laboratory, and grabbed some flasks and seeds, and dusted off his microscope. He started out to test, even to defeat, if necessary, his own explanations. Needham didn't heat his soups long enough—maybe there are little animals, or their eggs, which can stand a tremendous heat, who knows? So Spallanzani took some large glass flasks, round bellied with tapering necks. He scrubbed and washed and dried them till they stood in gleaming rows on his table. Then he put seeds of various kinds into some, and peas and almonds into others, and following that poured pure water into all of them. "Now I won't only heat these soups for a short time," he cried, "but I'll boil them for an hour!" He got his fires ready—then he grunted: "But how shall I close up my flasks? Corks might not be tight enough, they might let these infinitely wee things through." He pondered. "I've got it, I'll melt the necks of my bottles shut in a flame. I'll close them with glass—nothing, no matter how small, can sneak through glass!"

So he took his shining flasks one by one, and rolled their necks gently in a hot flame till each one was fused completely shut. He dropped some of them when they got too hot—he sizzled the skin of his fingers, he swore, and got new flasks to take the smashed ones' places. Then when his flasks were all sealed and ready, "Now for some real heat," he muttered, and for tedious hours he tended his bottles, as they bumped and danced in caldrons of boiling water. One set he boiled for a few minutes only. Another he kept in boiling water for a full hour.

At last, his eyes near stuck shut with tiredness, he lifted the flasks of stew steaming from their kettles, and put them carefully away—to wait for nervous anxious days to see whether any little animals would grow in them. And he did another thing, a simple one which I almost forgot to tell you about, he made another duplicate set of stews in flasks plugged up with corks, not sealed, and after boiling these for an hour put them away beside the others.

Then he went off for days to do the thousand things that were not enough to use up his buzzing energy. He wrote letters to the famous naturalist Bonnet, in Switzerland, telling him his experiments; he played football; he went hunting and fishing. He lectured about science, and told his students not of dry technicalities only, but of a hundred things—from the marvelous wee beasts that Leeuwenhoek had found in his mouth to the strange eunuchs and the veiled multitudinous wives of Turkish harems. At last he vanished and students and professors—and ladies—asked: "Where is the Abbé Spallanzani?" He had gone back to his rows of flasks of seed soup.

III

He went to the row of sealed flasks first, and one by one he cracked open their necks, and fished down with a slender hollow tube to get some of the soup inside them, in order to see whether any little animals at all had grown in these bottles that he had heated so long, and closed so perfectly against the microscopic creatures that might be floating in the dust of the outside air. He was not the lively sparkling Spallanzani now. He was slow, he was calm. Like some automaton, some slightly animated wooden man he put one drop of seed-soup after another before his lens.

He first looked at drop after drop of the soup from the sealed flasks which had been boiled for an hour, and his long looking was rewarded by—nothing. Eagerly he turned to the bottles that had been boiled for only a few minutes, and cracked their seals as before, and put drops of the soup inside them before his lens.

"What's this?" he cried. Here and there in the gray field of his lens he made out an animalcule playing and sporting about—these weren't large microbes, like some he had seen— but they were living little animals just the same.

"Why, they look like little fishes, tiny as ants," he muttered —and then something dawned on him "These flasks were sealed—nothing could get into them from the outside, yet here are little beings that have stood a heat of boiling water for several minutes!"

He went with nervous hands to the long row of flasks he had only stoppered with corks—as his enemy Needham had done—and he pulled out the corks, one by one, and fished in the bottles once more with his tubes. He growled excitedly, he got up from his chair. he seized a battered notebook and feverishly wrote down obscure remarks in a kind of scrawled shorthand. But these words meant that every one of the flasks which had been only corked, not sealed, was alive with little animals! Even the corked flasks which had been boiled for an hour, "were like lakes in which swim fishes of all sizes, from whales to minnows."

"That means the little animals get into Needham's flasks from the air!" he shouted. "And besides I have discovered a great new fact: living things exist that can stand boiling water and still live—you have to heat them to boiling almost an hour to kill them!"

It was a great day for Spallanzani, and though he did not know it, a great day for the world. Spallanzani had proved that Needham's theory of little animals arising spontaneously was wrong—just as the old master Redi had proved the idea was wrong that flies can be bred in putrid meat. But he had done more than that, for he had rescued the baby science of microbe hunting from a fantastic myth, a Mother Goose yarn that would have made all scientists of other kinds hold their noses at the very mention of microbe hunting as a sound branch of knowledge.

Excited, Spallanzani called his brother Nicolo, and his sister, and told them his pretty experiment. And then, bright-eyed, he told his students that life only comes from life; every living thing has to have a parent—even these wretched little animals! Seal your soup flasks in a flame, and nothing can get into them from outside. Heat them long enough, and everything, even those tough beasts that can stand boiling, will be killed. Do that, and you'll never find any living animals arising in any kind of soup—you could keep it till doomsday. Then he threw his work at Needham's head in a brilliant sarcastic paper, and the world of science was thrown into an uproar. Could Needham really be wrong? asked thoughtful men, gathered in groups under the high lamps and candles of the scientific societies of London and Copenhagen, of Paris and Berlin.

The argument between Spallanzani and Needham didn't stay in the academies among the highbrows. It leaked out through heavy doors onto the streets and crept into stylish drawingrooms. The world would have liked to believe Needham, for the people of the eighteenth century were cynical and gay; everywhere men were laughing at religion and denying any supreme power in nature, and they delighted in the notion that life could arise haphazardly. But Spallanzani's experiments were so clear and so hard to answer, even with the cleverest words. . . .

Meanwhile the good Needham had not been resting on his oars exactly; he was an expert at publicity, and to help his cause along he went to Paris and lectured about his mutton gravy, and in Paris he fell in with the famous Count Buffon. This count was rich; he was handsome; he loved to write about science; he believed he could make up hard facts in his head; he was rather too well dressed to do experiments. Besides he really knew some mathematics, and had translated Newton into French. When you consider that he could juggle most complicated figures, that he was a rich nobleman as well, you will agree that he certainly ought to know—without experimenting—whether little animals could come to life without fathers or mothers! So argued the godless wits of Paris.

Needham and Buffon got on famously. Buffon wore purple clothes and lace cuffs that he didn't like to muss up on dirty laboratory tables, with their dust and cluttered glassware and pools of soup spilled from accidentally broken flasks. So he did the thinking and writing, while Needham messed with the experiments. These two men then set about to invent a great theory of how life arises, a fine philosophy that every one could understand, that would suit devout Christians as well as witty atheists. The theory ignored Spallanzani's cold facts, but what would you have? It came from the brain of the great Buffon, and that was enough to upset any fact, no matter how hard, no matter how exactly recorded.

"What is it that causes these little animals to arise in mutton gravy, even after it has been heated, my Lord?" you can hear Needham asking of the noble count. Count Buffon's brain whirled in a magnificent storm of the imagination, then he answered: "You have made a great, a most momentous discovery, Father Needham. You have put your finger on the very source of life. In your mutton gravy you have uncovered the very force—it must be a force, everything is force—which creates life!"

"Let us then call it the Vegetative Force, my Lord," replied Father Needham.

"An apt name," said Buffon, and he retired to his perfumed study and put on his best suit and wrote—not from dry laboratory notes or the exact records of lenses or flasks but from his brain—he wrote, I say, about the marvels of this Vegetative Force that could make little animals out of mutton gravy and heated seed soups. In a little while Vegetative Force was on everybody's tongue. It accounted for everything. The wits made it take the place of God, and the churchmen said it was God's most powerful weapon. It was popular like a street song or an off color story—or like present day talk about relativity.

Worst of all, the Royal Society tumbled over itself to get ahead of the men in the street, and elected Needham a Fellow, and the Academy of Sciences of Paris made him an Associate. Meanwhile in Italy Spallanzani began to walk up and down his laboratory and sputter and rage. Here was a danger to science, here was ignoring of cold facts, without which science is nothing. Spallanzani was a priest of God, and God was perhaps reasonably sacred to him, he didn't argue with any one about that—but here was a pair of fellows who ignored his pretty experiments, his clear beautiful facts!

But what could Spallanzani do? Needham and Buffon had deluged the scientific world with words—they had not answered his facts, they had not shown where Spallanzani's experiment of the sealed flasks was wrong. The Italian was a fighter, but he liked to fight with facts and experiments, and here he was laying about him in this fog of big words, and hitting nothing. Spallanzani stormed and laughed and was sarcastic and bitter about this marvelous hoax, this mysterious Vegetative Force. It was the Force, prattled Needham, that had made Eve grow out of Adam's rib. It was the Force, once more, that gave rise to the remarkable worm-tree of China, which is a worm in winter, and then marvelous to say is turned by the Vegetative Force into a tree in summer! And much more of such preposterous stuff, until Spallanzani saw the whole science of living things in danger of being upset, by this alleged Vegetative Force with which, next thing people knew, Needham would be turning cows into men and fleas into elephants.

Then suddenly Spallanzani had his chance, for Needham made an objection to one of his experiments. "Your experiment does not hold water," he wrote to the Italian, "because you have heated your flasks for an hour, and that fierce heat weakens and so damages the Vegetative Force that it can no longer make little animals."

This was just what the energetic Spallanzani was waiting for, and he forgot religion and large classes of eager students and the pretty ladies that loved to be shown through his museum. He rolled up his wide sleeves and plunged into work, not at a writing desk but before his laboratory bench, not with a pen, but with his flasks and seeds and microscopes.

IV

"So Needham says heat damages the Force in the seeds, does he? Has he tried it? How can he see or feel or weigh or measure this Vegetative Force? He says it is in the seeds, well, we'll heat the seeds and see!"

Spallanzani got out his flasks once more and cleaned them. He brewed mixtures of different kinds of seeds, of peas and beans and vetches with pure water, until his work room almost ran over with flasks—they perched on high shelves, they sat on tables and chairs, they cluttered the floor so it was hard to walk around.

"Now, we'll boil a whole series of these flasks different lengths of time, and see which one generates the most little animals," he said, and then doused one set of his soups in boiling water for a few minutes, another for a half hour, another for an hour, and still another for two hours. Instead of sealing them in the flame he plugged them all up with corks—Needham said that was enough—and then he put them carefully away to see what would happen. He waited. He went off fishing and forgot to pull up his rod when a fish bit, he collected minerals for his museum, and forgot to take them home with him. He plotted for higher pay, he said masses, and studied the copulation of frogs and toads—and then disappeared once more to his dim work room with its regiments of bottles and weird machines. He waited.

If Needham were right, the flasks boiled for minutes should be alive with little animals, but the ones boiled for an hour or two hours should be deserted. He pulled out the corks one by one, and looked at the drops of soup through his lens and at last laughed with delight—the bottles that had been boiled for two hours actually had more little animals sporting about in them than the ones he had heated for a few minutes.

"Vegetative Force, what nonsense! so long as you only plug up your flasks with corks the little animals will get in from the air. You can heat your soups till you're black in the face—the microbes will get in just the same and grow, after the broth has cooled."

Spallanzani was triumphant, but then he did the curious thing that only born scientists ever do—he tried to beat his own idea, his darling theory—by experiments he honestly and shrewdly planned to defeat himself. That is science! That is the strange self-forgetting spirit of a few rare men, those curious men to whom truth is more dear than their own cherished whims and wishes. Spallanzani walked up and down his narrow work room, hands behind him, meditating—"Wait, maybe after all Needham has guessed right, maybe there is some mysterious force in these seeds that strong heat might destroy."

Then he cleaned his flasks again, and took some seeds, but instead of merely boiling them in water, he put them in a coffee-roaster and baked them till they were soot-colored cinders. Next he poured pure distilled water over them, growling: "Now if there was a Vegetative Force in those seeds, I have surely roasted it to death."

Days later when he came back to his flasks, with their soups brewed from the burned seeds, he smiled a sarcastic smile—a smile that meant squirmings for Buffon and Needham—for as one bottle after another yielded its drops of soup to his lens, every drop from every bottle was alive with wee animals that swam up and down in the liquid and went to and fro, living their funny limited little lives as gayly as any animals in the best soup made from unburned seeds. He had tried to defeat his own theory, and so trying had licked the pious Needham and the precious Buffon. They had said that heat would kill their Force so that no little animals could arise—and here were seeds charred to carbon, furnishing excellent food for the small creatures—this so-called Force was a myth! Spallanzani proclaimed this to all of Europe, which now began to listen to him.

Then he relaxed from his hard pryings into the loves and battles and deaths of little animals by making deep studies of the digestion of food in the human stomach—and to do this he experimented cruelly on himself. This was not enough, so he had to launch into weird investigations in the hot dark attic of his house, on the strange problem of how bats can keep from bumping into things although they cannot see. In the midst of this he found time to help educate his little nephews and to take care of his brother and sister, obscure beings who did not share his genius—but they were of his blood, and he loved them.

But he soon came back to the mysterious question of how life arises, that question which his religion taught him to ignore, to accept with blind faith as a miracle of the Creator. He didn't work with little animals only; instead he turned his curiosity onto larger ones, and began vast researches on the mating of toads. "What is the cause of the violent and persistent way in which the male toad holds the female?" he asked himself, and his wonder at this strange event set his ingenious brain to devising experiments of an unheard-of barbarity.

He didn't do them out of any fiendish whim to hurt the father toad-but this man must know every fact that could possibly be known about how new toads arose. What will make the toad let go this grip? And that mad priest cut off a male toad's hind legs in the midst of its copulation—but the dying animal did not relax that blind grasp to which nature drove it. Spallanzani mused over his bizarre experiment.

"This persistence of the toad," he said, "is due less to his obtuseness of feeling than to the vehemence of his passion."

In his sniffing search for knowledge which let him stop at nothing, he was led by an instinct that drove him into heartless experiments on animals—but it made him do equally cruel and fantastic tests on himself. He studied the digestion of food in the stomach, he gulped down hollowed-out blocks of wood with meat inside them, then tickled his throat and made himself vomit them up again so that he could find out what had happened to the meat inside the blocks. He kept insanely at this self-torture, until, as he admitted at last, a horrid nausea made him stop the experiments.

Spallanzani held immense correspondences with half the doubters and searchers of Europe. By mail he was a great friend of that imp, Voltaire. He complained that there were few men of talent in Italy, the air was too humid and foggy—he became a leader of that impudent band of scientists and philosophers who unknowingly prepared the bloodiest of revolutions while they tried so honestly to find truth and establish happiness and justice in the world. These men believed that Spallanzani had spiked once for all that nonsense about animals—even the tiniest ones—arising spontaneously. Led by Voltaire they cracked vast jokes about the Vegetative Force and its parents, the pompous Buffon and his laboratory boy, Father Needham.

"But there is a Vegetative Force," cried Needham, "a mysterious something—I'll admit you can't see it or weigh it—that can make life arise out of gravy or soup or out of nothing at all, perhaps. Maybe it can stand all of that roasting that Spallanzani applies to it, but what it needs particularly is a very elastic air to help it. And when Spallanzani boils his flasks for an hour, he hurts the elasticity of the air inside the flasks!"

Spallanzani was up in arms in a moment, and bawled for Needham's experiments. "Has he heated air to see if it got less elastic?" The Italian waited for experiments—and got only words. "Then I'll have to test it out myself," he said, and once again he put seeds in rows of flasks and sealed off their necks in a flame—and boiled them for an hour. Then one morning he went to his laboratory, and cracked off the neck of one of his bottles. . . .

He cocked his ear—he heard a little wh-i-s-s-s-s-t. "What's this," he muttered, and grabbed another bottle and cracked off its neck, holding his ear close by. Wh-i-s-s-st! There it was again. "That means the air is coming out of my bottle; or going into it," he cried, and he lighted a candle and ingeniously held it near the neck of a third flask as he cracked the seal.

The flame sucked inward toward the opening.

"The air's going in—that means the air in the bottle is less elastic than the air outside, that means maybe Needham is right!"

For a moment Spallanzani had a queer feeling at the pit of his stomach, his forehead was wet with nervous sweat, his world tottered around him. . . . Could that fool Needham have made a lucky stab, a clever guess about what heat did to air in sealed up flasks? Could this windbag knock out all of this careful finding of facts, which had taken so many years of hard work? For days Spallanzani went about troubled, and snapped at students to whom before he had been gentle, and tried to comfort himself by reciting Dante and Homer—and this only made him more grumpy. A relentless torturing imp pricked at him and this imp said: "Find out why the air rushes into your flasks when you break the seals—it may not have anything to do with elasticity." The imp woke him up in the night, it made him get tangled up in his masses. . . .

Then like a flash of lightning the explanation came to him and he hurried to his work bench—it was covered with broken flasks and abandoned bottles and its muddled disarray told his discouragement—he reached into a cupboard and took out one of his flasks. He was on the track, he would show Needham was wrong, and even before he had proved it he stretched himself with a heave of relief—so sure was he that the reason for the little whistling of air had come to him. He looked at the flasks, then smiled and said, "All the flasks that I have been using have fairly wide necks. When I seal them in the flame it takes a lot of heat to melt the glass till the neck is shut off—all that heat drives most of the air out of the bottle before it's sealed up. No wonder the air rushes in when I crack the seal!"

He saw that Needham's idea that boiling water outside the flask damaged the elasticity of the air inside was nonsense, nothing less. But how to prove this, how to seal up the flasks without driving out the air? His devilish ingenuity came to help him, and he took another flask, put seeds into it, and filled it partly with pure water. Then he rolled the neck of the bottle around in a hot flame until it melted down to a tiny narrow opening—very, very narrow, but still open to the air outside. Next he let the flask cool—now the air inside must be the same as the air outside—then he applied a tiny flame to the now almost needle-fine opening. In a jiffy the flask was sealed—without expelling any of the air from the inside. Content, he put the bottle in boiling water and watched it bumps and dance in the kettle for an hour and while he watched he recited verses and hummed gay tunes. He put the flask away for days, then one morning, sure of his result, he came to his laboratory to open it. He lighted a candle; he held it close to the flask neck; carefully he broke the seal—wh-i-s-s-s-t! But the flame blew away from the flask this time—the elasticity of the air inside the flask was greater than that outside!

All of the long boiling had not damaged the air at all—it was even more elastic than before—and elasticity was what Needham said was necessary for his wonderful Vegetative Force. The air in the flask was super-elastic, but fishing drop after drop of the soup inside, Spallanzani couldn't find a single little animal. Again and again, with the obstinacy of a Leeuwenhoek, he repeated the same experiment. He broke flasks and spilled boiling water down his shirt-front, he seared his hands, he made vast tests that had to be done over—but always he confirmed his first result.

V

Triumphant he shouted his last experiment to Europe, and Needham and Buffon heard it, and had to sit sullenly amid the ruins of their silly theory, there was nothing to say—Spallanzani had spiked their guns with a simple fact. Then the Italian sat down to do a little writing himself. A virtuoso in the laboratory, he was a fiend with his quill, when once he was sure his facts had destroyed Needham's pleasant myth about life arising spontaneously. Spallanzani was sure now that even the littlest beasts had to come—always—from beasts that had lived before. He was certain too, that a wee microbe always remained a microbe of the same kind that its parents had been, just as a zebra doesn't turn into a giraffe, or have musk-oxen for children, but always stays a zebra—and has zebra babies.

"In short," shouted Spallanzani, "Needham is wrong, and I have proved that there is a law and order in the science of animals, just as there is in the working of the stars."

Then he told the muddle that Needham would have turned the science of little animals into—if good facts hadn't been found to beat him. What animals this weird Vegetative Force could make—what tricks it could do—if it had only existed! "It could make," said Spallanzani, "a microscopic animal found sometimes in infusions, which like a new Protean, ceaselessly changes its form, appearing now as a body thin as a thread, now in an oval or spherical form, sometimes coiled like a serpent, adorned with rays and armed with horns. This remarkable animal furnishes Needham an example, to explain easily how the Vegetative Force produces now a frog and again a dog, sometimes a midge and at others an elephant, to-day a spider and to-morrow a whale, this minute a cow and the next a man."

So ended Needham—and his Vegetative Force. It became comfortable to live once more; you felt sure there was no mysterious sinister Force sneaking around waiting to change you into a hippopotamus.

Spallanzani's name glittered in all the universities of Europe; the societies considered him the first scientist of the day; Frederick the Great wrote long letters to him and with his own hand made him a member of the Berlin Academy; and Frederick's bitter enemy, Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria, put it over the great king by offering Spallanzani the job of professor in her ancient and run-down University of Pavia, in Lombardy. A pompous commission came, a commission of eminent Privy Councillors weighed down with letters and Imperial Seals and begged Spallanzani to put this defunct college on its feet. There were vast interminable arguments and bargainings about salary—Spallanzani always knew how to feather his nest—bargains that ended in his taking the job of Professor of Natural History and Curator of the Natural History Cabinet of Pavia.

Spallanzani went to the Museum, the Natural History Cabinet, and found that cupboard bare. He rolled up his sleeves, he lectured about everything, he made huge public experiments and he awed his students because his deft hands always made these experiments turn out successfully. He sent here and there for an astounding array of queer beasts and strange plants and unknown birds—to fill up the empty Cabinet. He climbed dangerous mountains himself and brought back minerals and precious ores; he caught hammer-head sharks and snared gay-plumed fowl; he went on incredible collecting expeditions for his museum—and to work off that tormenting energy that made him so fantastically different from the popular picture of a calm scientist. He was a Roosevelt with all of Teddy's courage and appeal to the crowd, but with none of Teddy's gorgeous inaccuracy.

In the intervals of this hectic collecting and lecturing he shut himself in his laboratory with his stews and his microscopic animals, and made long experiments to show that these beasts obey nature's laws, just as men and horses and elephants are forced to follow them. He put drops of stews swarming with microbes on little pieces of glass and blew tobacco smoke at them and watched them eagerly with his lens. He cried out his delight as he saw them rush about trying to avoid the irritating smoke. He shot electric sparks at them and wondered at the way the little animals "became giddy" and spun about, and quickly died.

"The seeds or eggs of the little animals may be different from chicken eggs or frog's eggs or fish eggs—they may stand the heat of boiling water in my sealed flasks—but otherwise these little creatures are really no different from other animals!" he cried. Then just after that he had to take back his confident words. . . .

"Every beast on earth needs air to live, and I am going to show just how animal these little animals are by putting them in a vacuum—and watching them die," said Spallanzani to himself, alone one day in his laboratory. He cleverly drew out some very thin tubes of glass, like the ones Leeuwenhoek had used to study his little animals. He dipped the tube into a soup that swarmed with his microbes; the fluid rushed up into the hair-fine pipe. Then Spallanzani sealed off one end of it, and ingeniously tied the other end to a powerful vacuum pump, and set the pump going, and stuck his lens against the thin wall of the tube. He expected to see the wee animals stop waving the "little arms which they were furnished to swim with;" he expected them to get giddy and then stop moving. . . .

The pump chugged on—and nothing whatever happened to the microbes. They went nonchalantly about their business and did not seem to realize there was such a thing as life-maintaining air! They lived for days, for weeks—and Spallanzani did the experiment again and again, trying to find something wrong with it. This was impossible—nothing can live without air—how the devil do these beasts breathe? He wrote his amazement in a letter to his friend Bonnet:

"The nature of some of these animalcules is astonishing! They are able to exercise in a vacuum the functions they use in free air. They make all of their courses, they go up and down in the liquid, they even multiply for several days in this vacuum. How wonderful this is! For we have always believed there is no living being that can live without the advantages air offers it."

Spallanzani was very proud of his imagination and his quick brain and he was helped along in this conceit by the flattery and admiration of students and intelligent ladies and learned professors and conquering kings. But he was an experimenter too—he was really an experimenter first, and he bent his head humbly when a new fact defeated one of the brilliant guesses of his brain.

Meanwhile this man who was so rigidly honest in his experiments, who would never report anything but the truth of what he found amid the smells and poisonous vapors and shining machines of his laboratory, this superbly honest. scientist, I say. was planning low tricks to increase his pay as Professor at Pavia. Spallanzani, the football player, the climber of mountains and explorer, this Spallanzani whined to the authorities at Vienna about his feeble health—the fogs and vapors of Pavia were like to make him die, he said. To keep him the Emperor had to increase his pay and double his vacations. Spallanzani laughed and cynically called his lie a political gesture! He always got everything he wanted. He got truth by dazzling experiments and close observation and insane patience; he obtained money and advancement by work— and by cunning plots and falsehoods; he received protection from religious persecution by becoming a priest!

Now, as he grew older, he began to hanker for wild researches in regions remote from his little laboratory. He must visit the site of ancient Troy whose story thrilled him so; he must see the harems and slaves and eunuchs, which to him were as much a part of natural history as his bats and toads and little animals of the seed infusions. He pulled wires, and at last the Emperor Joseph gave him a year's leave of absence and the money for a trip to Constantinople—for his failing health, which had never been more superb.

So Spallanzani put his rows of flasks away and locked his laboratory and said a dramatic and tearful good-by to his students; on the journey down the Mediterranean he got frightfully sea-sick, he was shipwrecked—but didn't forget to try to save the specimens he had collected on some islands. The Sultan wined and dined him, the doctors of the seraglios let him study the customs of the beauteous concubines . . . and afterward, good eighteenth century European that he was, Spallanzani told the Turks that he admired their hospitality and their architecture, but detested their custom of slavery and their hopeless fatalistic view of life. . . .

"We Westerners, through this new science of ours, are going to conquer the seemingly unavoidable, the apparently eternal torture and suffering of man," you can imagine him telling his polite but stick-in-the-mud Oriental friends. He believed in an all powerful God, but while he believed, the spirit of the searcher, the fact finder, flashed out of his eye, burdened all his thought and talk, forced him to make excuses for God by calling him Nature and the Unknown, compelled him to show that he had appointed himself first-assistant to God in the discovery and even the conquering of this unknown Nature.

After many months he returned overland through the Balkan Peninsula, escorted by companies of crack soldiers, entertained by Bulgarian dukes and Wallachian Hospodars. At last he came to Vienna, to pay his respects to his boss and patron, the Emperor Joseph II—it was the dizziest moment, so far as honors went, of his entire career. Drunk with success, he thought, you may imagine, of how all of his dreams had come true, and then

VI

While Spallanzani was on his triumphant voyage a dark cloud gathered away to the south, at his university, the school at Pavia that he had done so much to bring back to life. For years the other professors had watched him take their students away from them, they had watched—and ground their tusks and sharpened their razors—and waited.

Spallanzani by tireless expeditions and through many fatigues and dangers had made the once empty Natural History Cabinet the talk of Europe. Besides he had a little private collection of his own at his old home in Scandiano. One day, Canon Volta, one of his jealous enemies, went to Scandiano and by a trick got into Spallanzani's private museum; he sniffed around, then smiled an evil grin—here were some jars, and there a bird and in another place a fish, and all of them were labeled with the red tags of the University museum of Pavia! Volta sneaked away hidden in the dark folds of his cloak, and on the way home worked out his malignant plans to cook the brilliant Spallanzani's goose; and just before Spallanzani got home from Vienna, Volta and Scarpa and Scopoli let hell loose by publishing a tract and sending it to every great man and society in Europe, and this tract accused Spallanzani of the nasty crime of stealing specimens from the University of Pavia and hiding them in his own little museum at Scandiano.

His bright world came down around his ears; in a moment he saw his gorgeous career in ruins; in hideous dreams he heard the delighted cackles of men who praised him and envied him; he pictured the triumph of men whom he had soundly licked with his clear facts and experiments—he imagined even the return to life of that fool Vegetative Force. . . .

But in a few days he came back on his feet, the center of a dreadful scandal, it is true, but on his feet with his back to the wall ready to face his accusers. Gone now was the patient, hunter of microbes and gone the urbane correspondent of Voltaire. He turned into a crafty politician, he demanded an investigating committee and got it, he founded Ananias Clubs, he fought fire with fire.

He returned to Pavia and on his way there I wonder what his thoughts were—did he see himself slinking into the town, avoided by old admirers and a victim of malignant hissing whispers? Possibly, but as he got near the gates of Pavia a strange thing happened—for a mob of adoring students came out to meet him, told him they would stick by him, escorted him with yells of joy to his old lecture chair. The once self-sufficient, proud man’s voice became husky—he blew his nose— he could only stutteringly tell them what their devotion meant to him.

Then the investigating committee had him and his accusers appear before it, and knowing Spallanzani as you already do, you may imagine the shambles that followed! He proved to the judges that the alleged stolen birds were miserably stuffed, draggle-feathered creatures which would have disgraced the cabinet of a country school—they had been merely pitched out. He had traded the lost snakes and the armadillo to other museums and Pavia had profited by the trade; not only so, but Volta, his chief accuser, had himself stolen precious stones from the museum and given them to his friends. . . .

The judges cleared him of all guilt—though it is to-day not perfectly sure that he wasn’t a little guilty; Volta and his complotters were fired from the University, and all parties, including Spallanzani, were ordered by the Emperor to stop their deplorable brawling and shut up—this thing was getting to be a smell all over Europe—students were breaking up the classroom furniture about it, and other universities were snickering at such an unparalleled scandal. Spallanzani took a last crack at his routed enemies; he called Volta a perfect bladder full of wind and invented hideous and unprintably improper names for Scarpa and Scopoli; then he returned peacefully to his microbe hunting.

Many times in his long years of looking at the animalcules he had wondered how they multiplied. Often he had seen two of the wee beasts stuck together, and he wrote to Bonnet: “When you see two individuals of any animal kind united, you naturally think they are engaged in reproducing themselves.” But were they? He jotted his observations down in old notebooks and made crude pictures of them, but, impetuous as he was in many things, when it came to experiments or drawing conclusions—he was almost as cagy as old Leeuwenhoek had been.

Bonnet told Spallanzani’s perplexity about the way little animals multiplied to his friend, the clever but now unknown de Saussure. And this fellow turned his sharp eye through his clear lenses onto the breeding habits of animalcules. In a short while he wrote a classic paper, telling the fact that when you see two of the small beasts stuck together, they haven’t come together to breed. On the contrary—marvelous to say—these coupled beasts are nothing more nor less than an old animalcule which is dividing into two parts, into two new little animals! This, said de Saussure, was the only way the microbes ever multiplied—the joys of marriage were unknown to them!

Reading this paper, Spallanzani rushed to his microscope hardly believing such a strange event could be so—but careful looking showed that de Saussure was right. The Italian wrote the Swiss a fine letter congratulating him; Spallanzani was a fighter and something of a plotter; he was infernally ambitious and often jealous of the fame of other men, but he lost himself in his joy at the prettiness of de Saussure’s sharp observations. Spallanzani and these naturalists of Geneva were bound by a mysterious cement—a realization that the work of finding facts and fitting facts together to build the high cathedral of science is greater than any single finder of facts or mason of facts. They were the first haters of war—the first citizens of the world, the first genuine internationalists.

Then Spallanzani was forced into one of the most devilishly ingenious researches of his life. He was forced into this by his friendship for his pals in Geneva and by his hatred of another piece of scientific claptrap almost as bad as the famous Vegetative Force. An Englishman named Ellis wrote a paper saying de Saussure's observations about the little animals splitting into two was all wrong. Ellis admitted that the little beasts might occasionally break into two. "But that," cried Ellis, "doesn't mean they are multiplying! It simply means," he said, "that one little animal, swimming swiftly along in the water, bangs into another one amidships—and breaks him in half! That's all there is to de Saussure's fine theory.

"What is more," Ellis went on, "little animals are born from each other just as larger beasts come from their mothers. When I look carefully with my microscope, I can actually see young ones inside the old ones, and looking still more closely—you may not believe it—I can see grandchildren inside these young ones."

"Rot!" thought Spallanzani. All this stuff smelled very fishy to him, but how to show it wasn't true, and how to show that animalcules multiplied by breaking in two?

He was first of all a hard scientist, and he knew that it was one thing to say Ellis was feeble-minded, but quite

other to prove that the little animals didn’t bump into each other and so knock each other apart. In a moment the one way to decide it came to him—“All I have to do,” he meditated, “is to get one little beast off by itself, away from every other one where nothing whatever can bump into it—and then just sit and watch through the microscope to see if it breaks into two.” That was the simple and the only way to do it, no doubt, but how to get one of these infernally tiny creatures away from his swarms of companions? You can separate one puppy from a litter, or even a little minnow from its myriads of brothers and sisters. But you can’t reach in with your hands and take one animalcule by the tail—curse it—it is a million times too small for that.

Then this Spallanzani, this fellow who reveled in gaudy celebrations and vast enthusiastic lecturings, this hero of the crowd, this magnifico, crawled away from all his triumphs and pleasures to do one of the cleverest and most marvelously ingenious pieces of patient work in his hectic life. He did no less a thing than to invent a sure method of getting one animalcule—a few twenty-five thousandths of an inch long—a living animalcule, off by itself.

He went to his laboratory and carefully put a drop of seed soup swarming with animalcules on a clean piece of crystal glass. Then with a clean hair-fine tube he put a drop of pure distilled water—that had not a single little animal in it—on the same glass, close to the drop that swarmed with microbes.

“Now I shall trap one,” he muttered, as he trained his lens on the drop that held the little animals. He took a fine clean needle, he stuck it carefully into the drop of microbe soup—and then made a little canal with it across to the empty water drop. Quickly he turned his lens onto the passageway between the two drops, and grunted satisfaction as he saw the wriggling cavorting little creatures begin to drift through this little canal. He grabbed for a little camel’s-hair brush—“There! there’s one of the wee ones—just one, in the water drop!” Deftly he flicked the little brush across the small canal, wiping it out, so cutting off the chance of any other wee beast getting into the water drop to join its lonely little comrade.

“God!” he cried. “I’ve done it—no one’s ever done this before—I’ve got one animalcule all by himself; now nothing can bump him, now we’ll see if he’ll turn into two new ones!” His lens hardly quivered as he sat with tense neck and hands and arms, back bent, eye squinting through the glass at the drop with its single inhabitant. “How tiny he is,” he thought—“he is like a lone fish in the spacious abysses of the sea.”

Then a strange sight startled him, not less dramatic for its unbelievable littleness. The beast—it was shaped like a small rod—began to get thinner and thinner in the middle. At last the two parts of it were held together by the thickness of a spider web thread, and the two thick halves began to wriggle desperately—and suddenly they jerked apart. There they were, two perfectly formed, gently gliding little beasts, where there had been one before. They were a little shorter but otherwise they couldn’t be told from their parent. Then, what was more marvelous to see, these two children of the first one in a score of minutes split up again—and now there were four where there had been one!

Spallanzani did this ingenious trick a dozen times and got the same result and saw the same thing; and then he descended on the unlucky Ellis like a ton of brick and flattened into permanent obscurity Ellis and his fine yarn about the children and the grandchildren inside the little animals. Spallanzani was sniffish, he condescended, he advised, he told Ellis to go back to school and learn his a b c’s of microbe hunting. He hinted that Ellis wouldn’t have made his mistake if he’d read the fine paper of de Saussure carefully, instead of inventing preposterous theories that only cluttered up the hard job of getting genuine new facts from a stingy Nature.

A scientist, a really original investigator of nature, is like a writer or a painter or a musician. He is part artist, part cool searcher. Spallanzani told himself stories, he conceived himself the hero of a new epic exploration, he compared himself —in his writings even—to Columbus and Vespucci. He told of that mysterious world of microbes as a new universe, and thought of himself as a daring explorer making first groping expeditions along its boundaries only. He said nothing about the possible deadliness of the little animals—he didn’t like to engage, in print, in wild speculations—but his genius whispered to him that the fantastic creatures of this new world were of some sure but yet unknown importance to their big brothers, the human species. . . .

VII

Early in the year 1799, as Napoleon started thoroughly smashing an old world to pieces, and just as Beethoven was knocking at the door of the nineteenth century with the first of his mighty symphonies, war-cries of that defiant spirit of which Spallanzani was one of the chief originators—in the year 1799, I say, the great microbe hunter was struck with apoplexy. Three days later he was poking his energetic and irrepressible head above the bedclothes, reciting Tasso and Homer to the amusement and delight of those friends who had come to watch him die. But though he refused to admit it, this, as one of his biographers says, was his Canto di Cigno, his swan song, for in a few days he was dead.

Great Egyptian kings kept their names alive for posterity by having the court undertaker embalm them into expensive and gorgeous mummies. The Greeks and Romans had their likenesses wrought into dignified statues. Paintings exist of a hundred other distinguished men. What is left for us to see of the marvelous Spallanzani?

In Pavia there is a modest little bust of him and in the museum near by, if you are interested, you may see—his bladder. What better epitaph could there be for Spallanzani? What relic could more perfectly suggest the whole of his passion to find truth, that passion which stopped at nothing, which despised conventions, which laughed at hardship, which ignored bad taste and the feeble pretty fitness of things?

He knew his bladder was diseased. “Well, have it out after I’m dead,” you can hear him whisper as he lay dying. “Maybe you’ll find an astonishing new fact about diseased bladders.” That was the spirit of Spallanzani. This was the very soul of that cynical, sniffingly curious, coldly reasoning century of his—the century that discovered few practical things—but the same century that built the high clean house for Faraday and Pasteur, for Arrhenius and Emil Fischer and Ernest Rutherford to work in.