Microbe Hunters/Chapter 12

CHAPTER XII

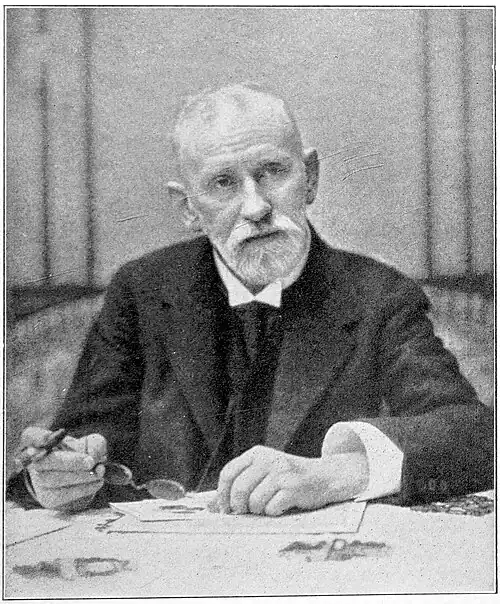

PAUL EHRLICH

THE MAGIC BULLET

I

Two hundred and fifty years ago, Antony Leeuwenhoek, who was a matter-of-fact man, looked through a magic eye, saw microbes, and so began this history. He would certainly have snorted a contemptuous Dutch sort of snort at anybody who called his microscope a magic eye.

Now Paul Ehrlich―who brings this history to the happy end necessary to all serious histories―was a gay man. He smoked twenty-five cigars a day; he was fond of drinking a seidel of beer (publicly) with his old laboratory servant and many seidels of beer with German, English and American colleagues; a modern man, there was still something medieval about him for he said: "We must learn to shoot microbes with magic bullets." He was laughed at for saying that, and his enemies cartooned him under the name "Doktor Phantasus."

But he did make a magic bullet! Alchemist that he was, he did something more outlandish than that, for he changed a drug that is the favorite poison of murderers into a saver of the lives of men. Out of arsenic he concocted a deliverer from the scourge of that pale corkscrew microbe whose attack is the reward of sin, whose bite is the cause of syphilis, the ill of the loathsome name. Paul Ehrlich had a most weird and wrong-headed and unscientific imagination: that helped him to make microbe hunters turn another corner, though alas, there have been few of them who have known what to do when they got around that corner, which is why this history has to stop with Paul Ehrlich.

Of course, it is sure as the sun following the dawn of tomorrow, that the high deeds of the microbe hunters have not come to an end; there will be others to fashion magic bullets. And they will be waggish men and original, like Paul Ehrlich, for it is not from a mere combination of incessant work and magnificent laboratories that such marvelous cures are to be got. . . . To-day? Well, to-day there are no microbe hunters who look you solemnly in the eye and tell you that two plus two makes five. Paul Ehrlich was that kind of a man. Born in March of 1854 in Silesia in Germany, he went to the gymnasium at Breslau, and his teacher of literature ordered him to write an essay, subject: "Life is a Dream."

"Life rests on normal oxidations," wrote that bright young Jew, Paul Ehrlich. "Dreams are an activity of the brain and the activities of the brain are only oxidations . . . dreams are a sort of phosphorescence of the brain!"

He got a bad mark for such smartness, but then he was always getting bad marks. Out of the gymnasium, he went to a medical school, or rather, to three or four medical schools―Ehrlich was that kind of a medical student. It was the opinion of the distinguished medical faculties of Breslau and Strasbourg and Freiburg and Leipsic that he was no ordinary student. It was also their opinion he was an abominably bad student, which meant that Paul Ehrlich refused to memorize the ten thousand and fifty long words supposed to be needed for the cure of sick patients. He was a revolutionist, he was part of the revolt led by that chemist, Louis Pasteur, and the country doctor, Robert Koch. His professors told Paul Ehrlich to cut up dead bodies and learn the parts of dead bodies; instead he cut up one part of a dead body into very thin slices and set to work to paint these slices with an amazing variety of pretty-colored aniline dyes, bought, borrowed, stolen from under his demonstrator's nose.

He hadn't a notion of why he liked to do that―though there is no doubt that to the end of his days this man’s chief joy (aside from wild scientific discussions over the beer tables) was in looking at brilliant colors, and making them.

"Ho, Paul Ehrlich―what are you doing there?” asked one of his professors, Waldeyer.

"Ja, Herr Professor, I am trying with different dyes!"

He hated classical training, he called himself a modern, but he had a fine knowledge of Latin, and with this Latin he used to coin his battle cries. For he worked by means of battle cries and slogans rather than logic. "Corpora non agunt nisi fixata!" he would shout, pounding the table till the dishes danced―"Bodies do not act unless fixed!" That phrase heartened him through thirty years of failure. "You see! You understand! You know!" he would say, waving his horn-rimmed spectacles in your face, and if you took him seriously you might think that Latin rigmarole (and not his searcher's brain) carried him to his final triumph. And in a way there is no doubt it did!

Paul Ehrlich was ten years younger than Robert Koch; he was in Cohnheim's laboratory on that day of Koch's first demonstration of the anthrax microbe; he was atheistical, so he needed some human god and that god was Robert Koch. Painting a sick liver Ehrlich had seen the tubercle germ before ever Koch laid eyes on it. Ignorant, lacking Koch's clear intelligence, he supposed those little colored rods were crystals. But when he sat that evening in the room in Berlin in March, 1882, and listened to Koch's proof of the discovery of the cause of consumption, he saw the light: "It was the most gripping experience of my scientific life," said Paul Ehrlich, long afterwards. So he went to Koch. He must hunt microbes too! He showed Robert Koch an ingenious way to stain that tubercle microbe―that trick is used, hardly changed, to this day. He would hunt microbes! And in the enthusiastic way he had he proceeded to get consumption germs all over himself: so he caught consumption and had to go to Egypt.

II

Ehrlich was thirty-four years old then, and if he had died in Egypt, he would certainly have been forgotten, or been spoken of as a color-loving, gay, visionary failure. He had the energy of a dynamo; he had believed you could treat sick people and hunt microbes at the same time; he had been head physician in a famous clinic in Berlin, but he was a very raw-nerved man and was fidgety under the cries of sufferers past helping and the deaths of patients who could not be cured. To cure them! Not by guess or by the bedside manner or by the laying on of hands or by waiting for Nature to do it—but how to cure them! These thoughts made him a bad doctor, because doctors should be sympathetic but not desperate about ills over which they are powerless. Then, too, Paul Ehrlich was a disgusting doctor because his brain was in the grip of dreams: he looked at the bodies of his patients: he seemed to see through their skins: his eyes became super-microscopes that saw the quivering stuff of the cells of these bodies as nothing more than complicated chemical formulas. Why of course! Living human stuff was only a business of benzene rings and side-chains, just like his dyes! So Paul Ehrlich (caring nothing for the latest physiological theories) invented a weird old-fashioned life-chemistry of his own; so Paul Ehrlich was anything but a Great Healer; so he would have been a failure――― But he didn't die!

"I will stain live animals!" he cried. "The chemistry of animals is like the chemistry of my dyes—staining them while they are still alive—that will tell me all about them!" So he took his favorite dye, which was methylene blue, and shot a little of it into the ear vein of a rabbit. He watched the color flow through the blood and body of the beast and mysteriously pick out and paint the living endings of its nerves blue―but no other part of it! How strange! He forgot all about his fundamental science for a moment. "Maybe methylene blue will kill pain then," he muttered. and he straightway injected this blue stuff into groaning patients, and maybe they were eased a little, but there were difficulties, of a more or less entertaining nature, which maybe frightened the patients—who can blame them?

He failed to invent a good pain-killer, but from this strange business of methylene blue pouncing on just one tissue out of all the hundred different kinds of stuff that living things are made of, Paul Ehrlich invented a fantastic idea which led him at last to his magic bullet.

"Here is a dye," he dreamed, "to stain only one tissue out of all the tissues of an animal's body—there must be one to hit no tissue of men, but to stain and kill the microbes that attack men." For fifteen years and more he dreamed that, before ever he had a chance to try it. . . .

In 1890 Ehrlich came back from Egypt; he had not died from tuberculosis; Robert Koch shot his terrible cure for consumption into him, still he did not die from tuberculosis—and presently he went to work in the Institute of Robert Koch in Berlin, in those momentous days when Behring was massacring guinea-pigs to save babies from diphtheria and the Japanese Kitasato was doing miraculous things to mice with lockjaw. Ehrlich was the life of that grave place! Koch would come into his pupil's crammed and topsy-turvy laboratory, that gleamed and shimmered with rows of bottles of dyes Ehrlich had no time to use—for you may be sure Koch was Tsar in that house and thought Ehrlich's dreams of magic bullets were nonsense. Robert Koch would come in and say:

"Ja, my dear Ehrlich, what do your experiments tell us to-day?"

Then would come a geyser of excited explanations from Paul Ehrlich, who was prying then into the way mice may become immune to those poisons of the beans called the castor and the jequirity:

"You see, I can measure exactly—it is always the same!—the amount of poison to kill in forty-eight hours a mouse weighing ten grams. . . . You know, I can now plot a curve of the way the immunity of my mice increases—it is as exact as experiments in the science of physics. . . . You understand, I have found how it is this poison kills my mice; it clots his blood corpuscles inside his arteries! That is the whole explanation of it . . ." and Paul Ehrlich waved test-tubes filled with brick-red clotted clumps of mouse blood at his famous chief, proving to him that the amount of poison to clot that blood was just the amount that would kill the mouse that the blood came from. Torrents of figures and experiment Paul Ehrlich poured over Robert Koch—

"But wait a moment, my dear Ehrlich! I can't follow you—please explain more clearly!"

"Certainly, Herr Doktor! That I can do right off!" Never for a moment does Ehrlich stop talking, but grabs a piece of chalk, gets down on his knees, and scrawls huge diagrams of his ideas over the laboratory floor—"Now, do you see, is that clear?"

There was no dignity about Paul Ehrlich! Neither about his attitudes, for he would draw pictures of his theories anywhere, with no more sense of propriety than an annoying little boy, on his cuffs and the bottoms of shoes, on his own shirt front to the distress of his wife, and on the shirt fronts of his colleagues if they did not dodge fast enough. Nor could you properly say Paul Ehrlich was dignified about his thoughts, because, twenty-four hours a day he was having the most outrageous thoughts of why we are immune or how to measure immunity or how a dye could be turned into a magic bullet. He left a trail of fantastic pictures of those thoughts behind him everywhere!

Just the same he was the most exact of men in his experiments. He was the first to cry out against the messy ways of microbe hunters, who searched for truth by pouring a little of this into some of that, and in that laboratory of Robert Koch he murdered fifty white mice where one was killed before, trying to dig up simple laws, to be expressed in numbers, that he felt lay beneath the enigmas of immunity and life and death. And that exactness, though it did nothing to answer those riddles, helped him at last to make the magic bullet.

III

Such was the gayety of Paul Ehrlich, and such his modesty—for he was always making straight-faced jokes at his own ridiculousness—that he easily won friends, and he was a crafty man too and saw to it that certain of these friends were men in high places. Presently, in 1896, he was director of a laboratory of his own; it was called the Royal Prussian Institute for Serum Testing. It was at Steglitz, near Berlin, and it had one little room that had been a bakery and another little room that had been a stable. "It is because we are not exact that we fail!" cried Ehrlich, remembering the bubble of the vaccines of Pasteur which had burst, and the balloon of the serums of Behring which had been pricked. "There must be mathematical laws to govern the doings of these poisons and vaccines and antitoxins!" he insisted, so this man with the erratic imagination walked up and down in those two dark rooms, smoking, explaining, expostulating, and measuring as accurately as God would let him with drops of poison broth and calibrated tubes of healing serum.

But laws? He would make an experiment. It would turn out beautifully. "You see! here is the reason of it!" he would say, and draw a queer picture of what a toxin must look like and what the chemistry of a body cell must look like, but as he went on working, as regiments of guinea-pigs marched to their doom, Paul Ehrlich found more exceptions to his simple theories than agreements with them. That didn't bother him, for, such was his imagination, that he invented new little supporting laws to take care of the exceptions, he drew stranger and stranger pictures, until his famous "Side-Chain" theory of immunity became a crazy puzzle, which could explain hardly anything, which could predict nothing at all. To his dying day Paul Ehrlich believed in his silly side-chain theory of immunity;

from all parts of the world critics knocked that theory to smithereens—but he never gave it up; when he couldn't find experiments to destroy his critics he argued at them with enormous hair-splittings like Duns Scotus and St. Thomas Aquinas. When he was beaten in these arguments at medical congresses it was his custom to curse—gayly—at his antagonist all the way home. "You see, my dear colleague!" he would cry, "that man is a SHAMELESS BADGER!" Every few minutes, at the top of his voice he yelled this, defying the indignant conductor to put him off the train.

So, in 1899, when he was forty-five, if he had died then, Ehrlich would certainly still have been called a failure. His efforts to find laws for serums had resulted in a collection of fantastic pictures that nobody took very seriously, they certainly had done nothing to turn feebly curative serums into powerful ones—what to do? First, this to do, thought Ehrlich, and he pulled his wires and cajoled his influential friends, and presently the indispensable and estimable Mr. Kadereit, his chief cook and bottle-washer, was dismounting that laboratory at Steglitz—they were moving to Frankfort-on-the-Main, away from the vast medical schools and scientific buzzings of Berlin. What to do? Well, Frankfort was near those factories where the master-chemists turned out their endless bouquets of pretty colors—what could be more important for Paul Ehrlich? Then there were rich Jews in Frankfort, and these rich Jews were famous for their public spirit, and money—Geld, that was one of his four big “G’s,” along with Geduld—patience, Geshick—cleverness and Gliick—luck, which Ehrlich always said were needed to find the magic bullet. So Paul Ehrlich came to Frankfort-on-the-Main, or rather, "WE came to Frankfort-on-the-Main," said the valuable Mr. Kadereit, who had the very devil of a time moving all of those dyes and that litter of be-penciled and dog-eared chemical journals.

Reading this history, you might think there was only one good kind of microbe hunter: the kind of searcher who stood on his own absolutely, who paid little attention to the work of other microbe hunters, who read nature and not books. But Paul Ehrlich was not that kind of man! He rarely observed nature, unless it was the pet toad in his garden, whose activities helped Ehrlich to prophesy the weather—it was Mr. Kadereit's first duty to bring plenty of flies to that toad. . . . No, Paul Ehrlich got his ideas out of books.

He lived among scientific books and subscribed to every chemical journal in every language he could read, and in several he couldn't read. Books littered his laboratory so that when visitors came and Ehrlich said: "I beg you, be seated!" there was no place for them to sit at all. Journals stuck out of the pockets of his overcoat—when he remembered to wear one—and the maid, bringing his coffee in the morning, fell over ever-growing mountains of books in his bedroom. Books, with the help of those expensive cigars, kept Paul Ehrlich poor. Mice built nests in the vast piles of books on the old sofa in his office. When he wasn't painting the insides of his animals and the outside of himself with his dyes, he was peering in these books. And what was important inside of those books, was in the brain of Paul Ehrlich, ripening, changing itself into those outlandish ideas of his, waiting to be used. That was where Paul Ehrlich got his ideas—you would never accuse him of stealing the ideas of others!—and queer things happened to those ideas of others when they stewed in Ehrlich's brain.

So now, in 1901, at the beginning of his eight-year search for the magic bullet he read of the researches of Alphonse Laveran. Laveran was the man, you remember, who discovered the malaria microbe, and very lately Laveran had taken to fussing with trypanosomes. He had shot those finned devils, which do evil things to the hind-quarters of horses and give them a disease called the mal de Caderas, into mice. Laveran had watched those trypanosomes kill those mice, one hundred times out of one hundred. Then Laveran had injected arsenic under the skins of some of those suffering mice. That had helped thema little, and killed many of the trypanosomes that gnawed at them, but not one of these mice ever got really better; one hundred out of one hundred died and that was as far as Alphonse Laveran ever got.

But reading this was enough to get Ehrlich started. "Ho! here is an excellent microbe to work with! It is large and easy to see. It is easy to grow in mice. It kills them with the most beautiful regularity! It always kills mice! What could be a better microbe than this trypanosome to use to try to find a magic bullet to cure? Because, if I could find a dye that would save, completely save, just one mouse!"

IV

So Paul Ehrlich, in 1902, set out on his hunt. He got out his entire array of gleaming and glittering and shimmering dyes. "Splen-did!" he cried as he squatted before cupboards holding an astounding mosaic of sloppy bottles. He provided himself with plenty of the healthiest mice. He got himself a most earnest and diligent Japanese doctor, Shiga, to do the patient job of watching those mice, of snipping a bit off the ends of their tails to get a drop of blood to look for the trypanosomes, of snipping another bit off the ends of the same tails to get a drop of blood to inject into the next mouse—to do the job, in short, that it takes the industry and patience of a Japanese to do. The evil trypanosomes of the mal de Caderas came in a doomed guinea-pig from the Pasteur Institute in Paris; into the first mouse they went, and the hunt was on.

They tried nearly five hundred dyes! What a completely unscientific hunter Paul Ehrlich was! It was like the first boatman hunting for the right kind of wood from which to make stout oars; it was like primitive blacksmiths clawing among metals for the best stuff from which to forge swords. It was, in short, the oldest of all the ways of man to get knowledge. It was the method of Trial and Sweating! Ehrlich tried; Shiga sweat. Their mice turned blue from this dye and yellow from that one, but the beastly finned trypanosomes of the mal de Caderas swarmed gayly in their veins, and killed those mice, one hundred out of every hundred!

That man Ehrlich smoked more of his imported cigars, even at night in bed he would awake to smoke them; he drank more mineral water; he read in more books, and he threw books at the head of poor Kadereit—who heaven knows could not be blamed for not knowing what dye would kill trypanosomes. He said Latin phrases; he propounded amazing theories of what these dyes ought to do. Never had any searcher coined so many utterly wrong theories. But then, in 1903, came a day when one of these wrong explanations came to help him.

Ehrlich was testing the pretty-colored but complicated benzopurpurin dyes on dying mice, but the mice were dying, with sickening regularity, from the mal de Caderas. Paul Ehrlich wrinkled his forehead—already it was like a corrugated iron roof from the perplexities and failures of twenty years—and he told Shiga:

"These dyes do not spread enough through the mouse's body! Maybe, my dear Shiga, if we change it a little—maybe, let us say, if we added sulfo-groups to this dye, it would dissolve better in the blood of the mouse!" Paul Ehrlich wrinkled his brow.

Now, while Paul Ehrlich's head was an encyclopedia of chemical knowledge, his hands were not the hands of an expert chemist. He hated complicated apparatus as much as he loved complicated theories. He didn't know how to manage apparatus. he was only a chemical dabber making endless fussy little starts with test-tubes, dumping in first this and then that to change the color of a dye, rushing out of his room to show the first person he met the result, waving the test-tube at him, shouting: "You understand? This is splen-did!" but as for delicate syntheses, those subtle buildings-up and changings of dyes, that was work for the master chemists. "But we must change this dye a little—then it will work!" he cried. Now Paul Ehrlich was a gay man and a most charming one, and presently back from the dye factory near by came that benzopurpurin color, with the sulfo-groups properly stuck onto it, "changed a little."

Under the skin of two white mice Shiga shot the evil trypanosomes of the mal de Caderas. A day passes. Two days go by. The eyes of those mice begin to stick shut with the mucilage of doom, their hair stands up straight with their dread of destruction—one day more and it will be all over with both of those mice. . . . But wait! Under the skin of one of those two mice Shiga sends a shot of that red dye—changed a little. Ehrlich watches, paces, mutters, gesticulates, shoots his cuffs. In a few minutes the ears of that mouse turn red, the white of his nearly eyes turn pinker than the pink of his albino pupils. That day is a day of fate for Paul Ehrlich, it is the day the god of chance is good, for, like snows before the sun of April, so those fell trypanosomes melt out of the blood of that mouse!

Away they go, shot down by the magic bullet, till the last one has perished. And the mouse? His eyes open. He snouts in the shavings in the booto of his cage and sniffs at the pitiful little body of his dead companion, the untreated one.

He is the first one of all mice to fail to die from the attack of the trypanosome.

Paul Ehrlich, by the grace of persistence, chance, God, and a dye called "Trypan Red" (its real chemical name would stretch across this page!) has saved him! How that encouraged this already too courageous man! "I have a dye to cure a mouse—I shall find one to save a million men," so dreamed that confident German Jew.

But not at once, alas and alas. With gruesome diligence Shiga shot in that trypan red, and some mice got better but others got worse. One, seemingly to be cured, would frisk about its cage, and then, after sixty days (!) would turn up seedy in the morning. Snip! went an end of its tail and the skillful Shiga would call Paul Ehrlich to see its blood matted with a writhing smarm of the fell trypanosomes of the mal de Caderas. Terrible beast are trypanosomes, sly, tough, as all despicable microbes are tough. And among the tough lot of them there are super-hardy ones. These beasts, when a Jew and a Japanese come along to have at them with a bright-colored dye, lap up that dye. They like it! Or they retreat discreetly to some out-of-the-way place in a mouse's carcass. There they wait their time to multiply in swarms. . . .

So, for his first little success, Paul Ehrlich paid with a thousand disappointments. The trypanosome of David Bruce's nagana and the deadly trypanosome of human sleeping sickness laughed at that trypan red! They absolutely refused to be touched by it! Then, what worked so beautifully with mice, failed completely when they came to try it on white rats and guinea-pigs and dogs. It was a grinding work, to be tackled only by such an impatient persistent man as Ehrlich, for had he not saved one mouse?—What waste! He used thousands of animals! I used to think, in the arrogance of my faith in science: "What waste!" But no. Or call it waste if you like, remembering that nature gets her most sublime results—so often—by being lavishly wasteful. And then remember that Paul Ehrlich had learned one lesson: change an apparently useless dye, a little, and it turns from a merely pretty color into something of a cure. That was enough to drive forward this too confident man.

All the time the laboratory was growing. To the good people of Frankfort Paul Ehrlich was a savant who understood all mysteries, who probed all the riddles of nature, who forgot everything. And how the people of Frankfort loved him for being so forgetful! It was said that this Herr Professor Doktor Ehrlich had to write himself postal cards several days ahead to remind himself of festive events in his family. "What a human being!" they said. "What a deep thinker!" said the cabbies who drove him every morning to his Institute. "That must be a genius!" said the grind-organ musicians whom he tipped heavily once a week to play dance music in the garden by the laboratory. "My best ideas come when I hear gay music like that," said Paul Ehrlich, who detested all highbrow music and literature and art. "What a democratic man, seeing how great he is!" said the good people of Frankfort, and they named a street after him. Before he was old he was legendary!

Then the rich people worshiped him. A great stroke of luck came in 1906. Mrs. Franziska Speyer, the widow of the rich banker, Georg Speyer, gave him a great sum of money to build the Georg Speyer House, to buy glassware and mice and expert chemists, who could put together the most complicated of his darling dyes with a twist of the wrist, who could make even the crazy drugs that Ehrlich invented on paper. Without this Mrs. Franziska Speyer, Paul Ehrlich might very well never have molded those magic bullets, for that was a job—you can watch what a job!—for a factory full of searchers. Here in this new Speyer House Ehrlich lorded it over chemists and microbe hunters like the president of a company that turned out a thousand automobiles a day. But he was really old-fashioned, and never pressed buttons. He was always popping into one or another of the laboratories every conceivable time of the day, scolding his slaves, patting them on the back, telling them of howling blunders he himself had made, laughing when he was told that his own assistants said he was crazy. He was everywhere! But there was always one way of tracking him down, for ever and again his voice could be heard, bawling down the corridors:

"Ka-de-reit! . . . Ci-gars!" or "Ka-de-reit! . . . Min-er-al wa-ter!"

V

The dyes were a great disappointment. The chemists muttered he was an idiot. But then, you must remember Paul Ehrlich read books. One day, sitting in the one chair in his office that wasn't piled high with them, peering through chemical journals like some Rosicrucian in search of the formula for the philosopher's stone, he came across a wicked drug. It was called "Atoxyl" which means: "Not poisonous." Not poisonous? Atoxyl had almost cured mice with sleeping sickness. Atoxyl had killed mice without sleeping sickness. Atoxyl had been tried on those poor darkies down in Africa. It had not cured them, but an altogether embarrassing number of those darkies had gone blind, stone blind, from Atoxyl before they had had time to die from sleeping sickness. So, you see, this Atoxyl was a sinister medicine that its inventors—had they been living—should have been ashamed of. It was made of a benzene ring, which is nothing more than six atoms of carbon chasing themselves round in a circle like a dog running round biting the end of his tail, and four atoms of hydrogen, and some ammonia and the oxide of arsenic—which everybody knows is poisonous.

"We will change it a little," said Paul Ehrlich, though he knew the chemists who had invented Atoxyl had said it was so built that it couldn't be changed without spoiling it. But every afternoon Ehrlich fussed around alone in his chemical laboratory, which was like no other chemical laboratory in the world. It had no retorts, no beakers, no flasks nor thermometers nor ovens—no, not even a balance! It was crude as the prescription counter of the country druggist (who also runs the postoffice) excepting that in its middle stood a huge table, with ranks and ranks of bottles—bottles with labels and bottles without, bottles with scrawled unreadable labels and bottles whose purple contents had slopped all over the labels. But that man's memory remembered what was in every one of those bottles! From the middle of this jungle of bottles a single Bunsen burner reared its head and spouted a blue flame. What chemist would not laugh at this laboratory?

Here Paul Ehrlich dabbled with Atoxyl, shouting: "Splen-did!", growling: "Un-be-liev-a-ble!", dictating to the long-suffering Miss Marquardt, bawling for the indispensable Kadereit. In that laboratory, with a chemical cunning the gods sometimes bestow on searchers who could never be chemists, Paul Ehrlich found that you can change Atoxyl, not a little but a lot, that it can be built into heaven knows how many entirely unheard-of compounds of arsenic, without spoiling the combination of benzene and arsenic at all!

"I can change Atoxyl!" Without his hat or coat Ehrlich hurried out of this dingy room to the marvelous workshop of Bertheim, chief of his chemist slaves. "Atoxyl can be changed—maybe we can change it into a hundred, a thousand new compounds of arsenic!" he exclaimed. . . . "Now, my dear Bertheim," and he poured out a thousand fantastic schemes. Bertheim? He could not resist that "Now my dear Bertheim!"

For the next two years the whole staff, Japs and Germans, not to mention some Jews, men and white rats and white mice, not to mention Miss Marquardt and Miss Leupold—and don't forget Kadereit!—toiled together in that laboratory which was like a subterranean forge of imps and gnomes. They tried this, they did that, with six hundred and six—that is their exact number—different compounds of arsenic. Such was the power of the chief imp over them, that this staff never stopped to think of the absurdity and the impossibility of their job, which was this: to turn arsenic from a pet weapon of murderers into a cure which no one was sure could exist for a disease Ehrlich hadn't even dreamed might be cured. These slaves worked as only men can work when they are inspired by a wrinkle-browed fanatic with kind gray eyes.

They changed Atoxyl! They developed marvelous compounds of arsenic which—hurrah!—would really cure mice. "We have it!" the staff would be ready to shout, but then, worse luck, when the fell trypanosomes of the mal de Caderas had gone, those marvelous cures turned the blood of the cured mice to water, or killed them with a fatal jaundice. . . . And—who would believe it?—some of those arsenic remedies made mice dance, not for a minute but for the rest of their lives round and round they whirled, up and down they jumped. Satan himself could not have schemed a worse torture for creatures just saved from death. It seemed ridiculous, hopeless, to try to find a perfect cure. But Paul Ehrlich? He wrote:

"It is very interesting that the only damage to the mice is that they become dancing mice. Those who visit my laboratory must be impressed by the great number of dancing mice it entertains. . . ." He was a sanguine man!

They invented countless compounds, and it was a business for despair. There was that strange affair of the arsenic fastness. When Ehrlich found that one big dose of a compound was too dangerous for his beasts, he tried to cure them by giving them a lot of little doses. But, curse it! The trypanosomes became immune to the arsenic, and refused to be killed off at all, and the mice died in droves. . . .

Such was the grim procession through the first five hundred and ninety-one compounds of arsenic. Paul Ehrlich kept cheering himself by telling himself fairy stories of marvelous new cures, stories that God and all nature could prove were lies. He drew absurd diagrams for Bertheim and the staff, pictures of imaginary arsenical remedies that they in their expert wisdom knew it was impossible to make. Everywhere he made pictures for his boys—who knew more than he did—on innumerable reams of paper, on the menu cards of restaurants and on picture post cards in beer halls. His men were aghast at his neglect of the impossible; they were encouraged by his indomitable mulishness. They said: "He is so enthusiastic!" and became enthusiastic with him. So, burning his candle at both ends, Paul Ehrlich came, in 1909, to his day of days.

VI

Burning his candle at both ends, for he was past fifty and his time was short, Paul Ehrlich stumbled onto the famous preparation 606—though you understand he could never have found it without the aid of that expert, Bertheim. Product of the most subtle chemical synthesis was this 606, dangerous to make because of the peril of explosions and fire from those constantly present ether vapors, and so hard to keep—the least trace of air changed it from a mild stuff to a terrible poison.

That was the celebrated preparation 606, and it rejoiced in the name: "Dioxy-diamino-arsenobenzol-dihydro-chloride." Its deadly effect on trypanosomes was as great as its name was long. At a swoop one shot of it cleaned those fell trypanosomes of the mal de Caderas out of the blood of a mouse—a wee bit of it cleaned them out without leaving a single one to carry news or tell the story. And it was safe! So safe—though it was heavily charged with arsenic, that pet poison of murderers. It never made mice blind, it never turned their blood to water, they never danced—it was safe!

"Those were the days!" muttered old Kadereit, long after. Already in those days he was growing stiff, but how he stumped about taking care of the "Father." "Those were the days, when we discovered the 606!" And they were the days—for what more hectic days (always excepting the days of Pasteur) in the whole history of microbe hunting? 606 was safe, 606 would cure the mal de Caderas, which was nice for mice and the hindquarters of horses, but what next? Next was that Paul Ehrlich made a lucky stab, that came from reading a theory with no truth in it. First Paul Ehrlich read—it had happened in 1906—of the discovery by the German zoölogist, Schaudinn, of a thin pale spiral-shaped microbe that looked like a corkscrew without a handle. (It was a fine discovery and Fritz Schaudinn was a fantastic fellow, who drank and saw weird visions. I wish I could tell you more of him.) Schaudinn spied out this pale microbe looking like a corkscrew without a handle. He named it the Spirocheta pallida. He proved that this was the cause of the disease of the loathsome name.

Of course Paul Ehrlich (who knew everything) read about that, but it particularly stuck in Ehrlich's memory that Schaudinn had said: "This pale spirochete belongs to the animal kingdom, it is not like the bacteria. Indeed, it is closely related to the trypanosomes. . . . Spirochetes may sometimes turn into trypanosomes. . . ."

Now, it was hardly more than a guess of that romantic Schaudinn that spirochetes had anything to do with trypanosomes, but it set Paul Ehrlich aflame.

"If the pale spirochete is a cousin of the trypanosome of the mal de Caderas—then 606 ought to hit that spirochete. . . . What kills trypanosomes should kill their cousins!" Paul Ehrlich was not bothered by the fact that there was no proof these two microbes were cousins. . . . Not he. So he marched towards his day of days.

He gave vast orders. He smoked more strong cigars each day. Presently regiments of fine male rabbits trooped into the Georg Speyer House in Frankfort-on-the-Main, and with these creatures came a small and most diligent Japanese microbe hunter, S. Hata. This S. Hata was accurate. He was capable. He could stand the strain of doing the same experiment a dozen times over and he could, so nimble was this S. Hata, do a dozen experiments at the same time. So he suited the uses of Ehrlich, who was a thorough man, do not forget it!

Hata started out by doing long tests with 606 on spirochetes not so pale or so dangerous. There was that spirochete fatal to chickens. . . . The results? "Un-heard . . . of! In-cred-i-ble!" shouted Paul Ehrlich. Chickens and roosters whose blood swarmed with that microbe received their shot of 606. Next day the chickens were clucking and roosters strutting—it was superb. But that disease of the loathsome name?

On the 31st of August, 1909, Paul Ehrlich and Hata stood before a cage in which sat an excellent buck rabbit. Flourishing in every way was this rabbit, excepting for the tender skin of his scrotum, which was disfigured with two terrible ulcers, each bigger than a twenty-five-cent piece. These sores were caused by the gnawing of the pale spirochete of the disease that is the reward of sin. They had been put under the skin of that rabbit by S. Hata a month before. Under the microscope—it was a special one built for spying just such a thin rogue as that pale microbe—under this lens Hata put a wee drop of the fluid from these ugly sores. Against the blackness of the dark field of this special microscope, gleaming in a powerful beam of light that hit them sidewise, shooting backwards and forwards like ten thousand silver drills and augers, played myriads of these pale spirochetes. It was a pretty picture, to hold you there for hours, but it was sinister—for what living things can bring worse plague and sorrow to men?

Hata leaned aside. Paul Ehrlich looked down the shiny tube. Then he looked at Hata, and then at the rabbit.

"Make the injection,” said Paul Ehrlich. And into the ear- vein of that rabbit went the clear yellow fluid of the solution of 606, for the first time to do battle with the disease of the loathsome name.

Next day there was not one of those spiral devils to be found in the scrotum of that rabbit. His ulcers? They were drying already! Good clean scabs were forming on them. In less than a month there was nothing to be seen but tiny scabs—it was like a cure of Bible times—no less! And a little while after that Paul Ehrlich could write:

"It is evident from these experiments that, if a large enough dose is given, the spirochetes can be destroyed absolutely and immediately with a single injection!"

This was Paul Ehrlich's day of days. This was the magic bullet! And what a safe bullet! Of course there was no danger in it—look at all these cured rabbits! They had never turned a hair when Hata shot into their ear-veins doses of 606 three times as big as the amount that surely and promptly cured them. It was more marvelous than his dreams, which all searchers in Germany had smiled at. Now he would laugh! "It is safe!" shouted Paul Ehrlich, and you can guess what visions floated into that too confident man's imagination. "It is safe—perfectly safe!" he assured every one. But at night, sitting in the almost unbreathable fog of cigar smoke in his study, alone, among those piles of books and journals that heaped up fantastic shadows round him, sitting there before the pads of blue and green and yellow and orange note paper on which every night he scrawled hieroglyphic directions fo1 the next day’s work of his scientific slaves, Paul Ehrlich, noted as a man of action, whispered:

"Is it safe?"

Arsenic is the favorite poison of murderers. . . . "But how wonderfully we have changed it!" Paul Ehrlich protested.

What saves mice and rabbits might murder men. . . . "The step from the laboratory to the bedside is dangerous—but it must be taken!" answered Paul Ehrlich. You remember his gray eyes, that were so kind.

But, heigho! Here was the next morning, the brave light of the bright morning. Here was the laboratory with its cured rabbits, here was that wizard, Bertheim—how he had twisted that arsenic through all these six hundred and six compounds. That man could not go wrong. So many of them had been dangerous that this six hundred and sixth one must be safe. . . . Bravo! Here was the mixed good smell of a hundred experimental animals and a thousand chemicals. Here were all these men and women, how they believed in him! So, let’s go! Let us try it!

At bottom Paul Ehrlich was a gambler, as who of the great line of the microbe hunters has not been?

And before that sore on the scrotum of the first rabbit had shed its last scab, Paul Ehrlich had written to his friend, Dr. Konrad Alt: "Will you be so good as to try this new preparation, 606, on human beings with syphilis?"

Of course Alt wrote back: “Certainly!" which any German doctor—for they are right hardy fellows—would have replied.

Came 1910, and that was Paul Ehrlich's year. One day, that year, he walked into the scientific congress at Koenigsberg, and there was applause. It was frantic, it was long, you would think they were never going to let Paul Ehrlich say his say. He told of how the magic bullet had been found at last. He told of the terror of the disease of the loathsome name, of those sad cases that went to horrible disfiguring death, or to what was worse—the idiot asylums. They went there in spite of mercury—mercury fed them and rubbed into them and shot into them until their teeth were like to drop out of their gums, He told of such cases given up to die. One shot of the compound six hundred and six, and they were up, they were on their feet. They gained thirty pounds. They were clean once more—their friends would associate with them again. . . . Paul Ehrlich told, that day, of healings that could only be called Biblical! Of a wretch, so dreadfully had the pale spirochetes gnawed at his throat that he had had to be fed liquid food through a tube for months. One shot of the 606, at two in the afternoon, and at supper time that man had eaten a sausage sandwich! There were poor women, innocent sufferers from the sins of their men—there was one woman with pains in her bones, such pains she had been given morphine every night for years, to give her a little sleep. One shot of compound six hundred and six. She had gone to sleep, quiet and deep, with no morphine, that very night. It was Biblical, no less. It was miraculous—no drug nor herb of the old women and priests and medicine men of the ages had ever done tricks like that. No serum nor vaccine of the modern microbe hunters could come near to the beneficent slaughterings of the magic bullet, compound six hundred and six.

Never was there such applause.

Never has it been better earned, for that day Paul Ehrlich—forget for a moment the false hopes raised and the troubles that followed—that day Paul Ehrlich had led searchers around a corner.

But, to every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. What is true in the realm of lifeless things is true in the lives of such men as Paul Ehrlich. The whole world bawled for salvarsan. That was what Ehrlich—we must forgive him his grandiloquence—called compound six hundred and six. Then, in the laboratory of the Georg Speyer House, Bertheim and ten assistants—worn these fellows were before they started it—turned out hundreds of thousands of doses of this marvelous stuff. They did the job of a chemical factory in their small laboratory, in the dangerous fumes of ether, in the fear that one little slip might rob a hundred men and women of life, for it was two-edged stuff, that salvarsan. And Ehrlich? Now he was only a shell of a man, with diabetes—and why did he keep on smoking more cigars?—now Ehrlich burned the candle in the middle.

He was everywhere in the Georg Speyer House. He directed the making of compounds that would be still more wonderful—so he hoped. He chased around so that even Kadereit couldn't keep track of him. He dictated hundreds of enthusiastic letters to Martha Marquardt, he read thousands of letters from every corner of the world, he kept records, careful records they were too, of every one of the sixty-five thousand doses of salvarsan injected in the year 1910. He kept them—this was like that strangely systematic man!—on a big sheet of paper tacked to the inside of the cupboard door of his office, from the top to the bottom of that door in tiny scrawls, so that he had constantly to squat on his heels or stretch up on tiptoe and strain his eyes to read them.

As the list grew, there were records of most extraordinary cures, but there were reports it was not pleasant to read, too, records that told of hiccups and vomitings and stiffenings of legs and convulsions and death—every now and then a death in people who had no business dying, coming right after injections of the salvarsan.

How he worked to explain them! How he wore himself to a shred to avoid them, for Paul Ehrlich was not a hard-boiled man. He made experiments; he conducted immense correspondences in which he asked minute questions of just how the injections had been made. He devised explanations, on the margins of the playing cards he used for his games of solitaire each evening, on the backs of those blood-and-thunder murder mysteries that were the one thing he read—so he imagined—to rest. But he never rested! Those disasters pursued him and marred his triumph. . . .

The wrinkles deepened to ditches on his forehead. The circles darkened under those gray eyes that still, but not so often, danced with that owlish humor.

So this compound six hundred and six, saving its thousands from death, from insanity, from the ostracism worse than death that came to those sufferers whose bodies the pale spirochete gnawed until they were things for loathing, this 606 began killing its tens. Paul Ehrlich wore his too feeble body to a shadow, trying to explain a mystery too deep for explanation. There is no light on that mystery now, ten years after Ehrlich smoked the last of his black cigars. So it was that this triumph of Paul Ehrlich was at the same time the last disproof of his theories, which were so often wrong. "Compound six hundred and six unites chemically with the spirochetes and kills them—it does not unite chemically with the human body and so can do no damage!" That had been his theory. . . .

But alas! What is the chemistry of what this subtle 606 does to the still more subtle—and unknown—machine that is the human body? Nothing is known about it even now. Paul Ehrlich paid the penalty for his fault—which may be forgiven him seeing the blessings he has brought to men—his fault of not foreseeing that once in every so many thousands of bodies a magic bullet may shoot two ways. But then, the microbe hunters of the great line have always been gamblers: let us think of the good brave adventurer Paul Ehrlich was and the thousands he has saved.

Let us remember him, trail-breaker who turned a corner for microbe hunters and started them looking for magic bullets. Already (though it is too soon to tell the whole story) certain obscure searchers, some of them old slaves of Paul Ehrlich, sweating in the great dye factories of Elberfeld, have hit upon a most fantastical drug. Its chemistry is kept a secret. It is called "Bayer 205." It is a mild mysterious powder that cures the hitherto always fatal sleeping sickness of Rhodesia and Nyassaland. That was the ill, you remember, that the hard man, David Bruce, fought his last fight, in vain, to prevent. It does outlandish things to the cells and fluids of the human body—you would say they were fibs and fairy tales if you heard the queer things that drug can do! But what is best, it slaughters microbes! It kills them beautifully, precisely, with a completeness that must make Paul Ehrlich wriggle in his grave—and when it doesn't kill microbes it tames them.

It is as sure as the sun following the dawn of to-morrow that there will be other microbe hunters to mold other magic bullets, surer, safer, bullets to wipe out for always the most malignant microbes of which this history has told. Let us remember Paul Ehrlich, who broke this trail. . . .

This plain history would not be complete if I were not to make a confession, and that is this: that I love these microbe hunters, from old Antony Leeuwenhoek to Paul Ehrlich. Not especially for the discoveries they have made nor for the boons they have brought mankind. No. I love them for the men they are. I say they are, for in my memory every man jack of them lives and will survive until this brain must stop remembering.

So I love Paul Ehrlich—he was a gay man who carried his medals about with him all mixed up in a box never knowing which ones to wear on what night. He was an impulsive man who has, on occasion, run out of his bedroom in his shirt tail to greet a fellow microbe hunter who came to call him out for an evening of wassail.

And he was an owlish man! "You say a great work of the mind, a wonderful scientific achievement?" he repeated after a worshiper who told him that was what the discovery of 606 was.

"My dear colleague," said Paul Ehrlich, "for seven years of misfortune I had one moment of good luck!"

END OF

Microbe Hunters