Microbe Hunters/Chapter 10

CHAPTER X

ROSS VS. GRASSI

MALARIA

I

The last ten years of the nineteenth century were as unfortunate for ticks, bugs, and gnats as they were glorious for the microbe hunters. Theobald Smith had started them off by scotching the ticks that carried Texas fever; a little later and six thousand miles away David Bruce, stumbling through the African bush, got onto the trail of the tsetse fly, accused him, convicted him. How melancholy and lean have been the years, since then, for that murderous tick whose proper name is Bo-ophilus bovis, and you may be sure that since those searchings of David Bruce, the tsetses have had to bootleg for the blood of black natives and white hunters, and missionaries. And now alas for mosquitoes! Malaria must be wiped from the earth. Malaria can be destroyed! Because, by the middle of 1899, two wrangling and not too dignified microbe hunters had proved that the mosquito—and only one particular kind of mosquito—was the criminal in the malaria mystery.

Two men solved that puzzle. The one, Ronald Ross, was a not particularly distinguished officer in the medical service of India. The other, Battista Grassi, was a very distinguished Italian authority on worms, white ants, and the doings of eels. You cannot put one before the other in the order of their merit—Ross would certainly have stopped short of solving the puzzle without Grassi. And Grassi might (though I am not so sure of that!) have muddled for years if the searchings of Ross had not given him hints. So there is no doubt they helped each other, but unhappily for the Dignity of Science, before the huzzahs of the rescued populations had died away, Battista Grassi and Ronald Ross were in each other's hair on the question of who did how much. It was deplorable. To listen to these two, you would think each would rather this noble discovery had remained buried, than have the other get a mite of credit for it. Indeed, the only consolation to be got from this scientific brawl—aside from the saving of human lives—is the knowledge that microbe hunters are men like the rest of us, and not stuffed shirts or sacred cows, as certain historians would have us believe. They sat there, Battista Grassi and Ronald Ross, indignant co-workers in a glorious job, in the midst of their triumph, with figurative torn collars and metaphorical scratched faces. Like two quarrelsome small boys they sat there.

II

For the first thirty-five years of his life Ronald Ross tried his best not to be a microbe hunter. He was born in the foothills of the Himalayas in India, and knowing his father (if you believe in eugenics) you might suspect that Ronald Ross would do topsy-turvy things with his life. Father Ross was a ferocious looking border-fighting English general with belligerent side-whiskers, who was fond of battles but preferred to paint landscapes. He shipped his son Ronald Ross back to England before he was ten, and presently, before he was twenty, Ronald was making a not too enthusiastic pass at studying medicine, failing to pass his examinations because he preferred composing music to the learning of Latin words and the cultivation of the bedside manner. This was in the eighteen-seventies, mind you, in the midst of the most spectacular antics of Pasteur, but from the autobiography of Ronald Ross, which is a strange mixture of cleverness and contradiction, of frank abuse of himself and of high enthusiasm for himself, you can only conclude that this revolution in medicine left Ronald Ross cold.

But he was, for all that, something of a chaser of moonbeams, because, finding that his symphonies didn't turn out to be anything like those of Mozart, he tried literature, in the grand manner. He neglected to write prescriptions while he nursed his natural bent for epic drama. But publishers didn't care for these masterpieces, and when Ross printed them at his own expense, the public failed to get excited about them. Father Ross became indignant at this dabbling and threatened to stop his allowance, so Ronald (he had spunk) got a job as a ship's doctor on the Anchor Line between London and New York. On this vessel he observed the emotions and frailties of human nature in the steerage, wrote poetry on the futility of life, and got up his back medical work. Finally he passed the examination for the Indian Medical Service, found the heat of India detestable, but was glad there was little medical practice to attend to, because it left him time to compose now totally forgotten epics and sagas and blood-and-thunder romances. That was the beginning of the career of Ronald Ross!

Not that there was no chance for him to hunt microbes in India. Microbes? The very air was thick with them. The water was a soup of them. All around him in Madras were the stinking tanks breeding the Asiatic cholera; he saw men die in thousands of the black plague; he heard their teeth rattle with the ague of malaria, but he had no ears or eyes or nose for all that—for now he forgot literature to become a mathematician. He shut himself up inventing complicated equations. He devised systems of the universe of a grandeur he thought equal to Newton's. He forgot about these to write another novel. He took twenty-five-mile-a-day walking trips in spite of the heat and then cursed India bitterly because it was so hot. He was ordered off to Burma and to the Island of Moulmein, and here he did remarkable surgical operations—"which cured most of the cases"—though he had never presumed to be a surgeon. He tried everything but impressed hardly anybody; years passed, and, when the Indian Medical Service failed to recognize his various abilities, Ronald Ross cried: "Why work?"

He went back to England on his first furlough in 1888, and there something happened to him, an event that is often an antidote to cynicism and a regulator of confused multitudinous ambitions. He met, he was smitten with, and presently he married Miss Rosa Bloxam. Back in India—though he wrote another novel called "Child of Ocean" and invented systems of shorthand and devised phonetic spellings for the writing of verse and was elected secretary of the Golf Club—he began to fumble at his proper work. In short he began to turn a microscope, with which he was no expert, on to the blood of malarious Hindus. The bizarre, many-formed malaria microbe had been discovered long ago in 1880 by a French army surgeon, Laveran, and Ronald Ross, who was as original as he was energetic and never did anything the way anybody else did it, tried to find this malaria germ by methods of his own.

Of course, he failed again. He bribed, begged, and wheedled drops of blood out of the fingers of hundreds of aguey East Indians. He peered. He found nothing. "Laveran is certainly wrong! There is no germ of malaria!" said Ronald Ross, and he wrote four papers trying to prove that malaria was due to intestinal disturbances. That was his start in microbe hunting!

III

He went back to London in 1894, plotting to throw up medicine and science. He was thirty-six. "Everything I had tried had failed," he wrote, but he consoled himself by imagining himself a sad defiant lone wolf: "But my failure did not depress me. . . . it drove me aloft to peaks of solitude. . . . Such a spirit was a selfish spirit but nevertheless a high one. It desired nothing, it sought no praise. . . . it had no friends, no fears, no loves, no hates."

But as you will see, Ronald Ross knew nothing of himself, for when he got going at his proper work, there was never a less calm and more desirous spirit than his. Nor a more enthusiastic one. And how he could hate!

When Ross returned to London he met Patrick Manson, an eminent and mildly famous English doctor. Manson had got himself medically notorious by discovering that mosquitoes can suck worms out of the blood of Chinamen (he had practiced in Shanghai); Manson had proved—this is remarkable!—that these worms can even develop in the stomachs of mosquitoes. Manson was obsessed by mosquitoes, he believed they were among the peculiar creatures of God, he was convinced they were important to the destinies of man, he was laughed at, and the medical wiseacres of Harley Street called him a "pathological Jules Verne." He was sneered at. And then he met Ronald Ross—whom the world had sneered at. What a pair of men these two were! Manson knew so little about mosquitoes that he believed they could only suck blood once in their lives, and Ross talked vaguely about mosquitoes and gnats not knowing that mosquitoes were gnats. And yet—

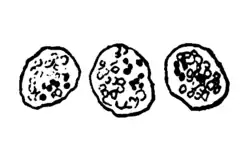

Manson took Ross to his office, and there he set Ross right about the malaria microbe of Laveran that Ross did not believe in. He showed Ronald Ross the pale malaria parasites, peppered with a blackish pigment. Together they watched these germs, fished out of the blood of sailors just back from the equator, turn into little squads of spheres inside the red blood cells, then burst out the blood cells. "That happens just when the man has his chill,” explained Manson. Ross was amazed at the mysterious transformations and cavortings of the malaria germs in the blood. After those spheres had galloped out of the corpuscles, they turned suddenly into crescent shapes, then those crescents would shoot out two, three, four, sometimes six long whips, which lashed and curled about and made the beast look like a microscopic octopus.

"That, Ross, is the parasite of malaria—you never find it in people without malaria—but the thing that bothers me is: How does it get from one man to another?"

Of course that didn't really bother Patrick Manson at all. Every cell in that man's brain had in it a picture of a mosquito or the memory of a mosquito or a speculation about a mosquito. He was a mild man, not a terrific worker himself, but intensely prejudiced on this subject of mosquitoes. And he appreciated Ronald Ross's energy of a dynamo, he knew Ronald Ross adored him, and he remembered Ross was presently returning to India. So one day, as they walked along Oxford Street, Patrick Manson took his jump: "Do you know, Ross," he said, "I have formed the theory that mosquitoes carry malaria . . . ?" Ronald Ross did not sneer or laugh.

Then the old doctor from Shanghai poured his fantastic theory over this young man whom he wanted to make his hands: "The mosquitoes suck the blood of people sick with malaria . . . the blood has those crescents in it . . . they get into the mosquito's stomach and shoot out those whips . . . the whips shake themselves free and get into the mosquito's carcass. . . . The whips turn into some tough form like the spore of an anthrax bacillus. . . .The mosquitoes die . . . they fall into water . . . people drink a soup of dead mosquitoes. . . ."

This, mind you, was a story, a romance, a purely trumped-up guess on the part of Patrick Manson. But it was a passionate guess, and by this time you have learned, maybe, that one guess, guessed enthusiastically enough—one guess in a billion may lead to something in this strange game of microbe hunting. So this pair walked down Oxford Street. And Ross? Well, he talked about gnats and mosquitoes and did not know that mosquitoes were gnats. But Ross listened to Manson. . . . Mosquitoes carry malaria? That was an ancient superstition—but here was Doctor Manson, thinking about nothing else. Mosquitoes carry malaria? Well, Ross's books had not sold; his mathematics were ignored. . . . But here was a chance, a gamble! If Ronald Ross could prove mosquitoes were to blame for malaria! Why, a third of all the people in the hospitals in India were in bed with malaria. More than a million a year died, directly or indirectly, because of malaria, in India alone! But if mosquitoes were really to blame—it would be easy!—malaria could be absolutely wiped out. . . . And if he, Ronald Ross, were the man to prove that!

"It is my duty to solve the problem," Ross said. Fictioneer that he was, he called it: "The Great Problem." And he threw himself at Manson's feet. "I am only your hands—it is your problem!" he assured the doctor from China.

"Before you go, you should find out something about mosquitoes," advised Manson, who himself didn't know whether there were ten different kinds of mosquitoes, or ten thousand, who thought mosquitoes could live only three days after they had bitten. So Ross (who didn't know mosquitoes were gnats) looked all over London for books about mosquitoes—and couldn't find any. Too little of a scholar, then, to think of looking in the library of the British Museum, Ross was sublimely ignorant, but maybe that was best, for he had nothing to unlearn. Never has such a green searcher started on such a complicated quest. . . .

He left his wife and children in England, and on the twenty-eighth of March, 1895, he set sail for India, with Patrick Manson's blessing, and full of his advice. Manson had outlined experiments—but how did one go about doing an experiment? But mosquitoes carry malaria! On with the mosquito hunt! On the ship Ross pestered the passengers, begging them to let him prick their fingers for a drop of blood. . . . He looked for mosquitoes, but they were not among the discomforts of the ship, so he dissected cockroaches—and he made an exciting discovery of a new kind of microbe in an unfortunate flying fish that had flopped on the deck. He was ordered to Secunderabad, a desolate military station that sat between hot little lakes in a huge plain dotted with horrid heaps of rocks, and here began to work with mosquitoes. He had to take care of patients too, he was only a doctor and the Indian Government —who can blame them?—would not for a moment recognize Ronald Ross as an official authentic microbe hunter or mosquito expert. He was alone. Everybody was against him from his colonel who thought him an insane upstart to the black-skinned boys who feared him for a dangerous nuisance (he was always wanting to prick their fingers!). The other doctors! They did not even believe in the malaria parasite. When they challenged him to show them the germs in the patient's blood, Ross went to the fray full of confidence, dragging after him a miserable Hindu whose blood was rotten with malaria microbes, but when the fatal test was made—curse it!—that wretched Hindu suddenly felt fit as a fiddle. His microbes had departed from him. The doctors roared with laughter. But Ronald Ross kept at it.

He started out to follow Manson's orders. He captured mosquitoes, any kind of mosquito, he couldn't for the life of him have told you what kind they were. He let the pests loose under nets over beds on which lay naked and foolishly superstitious dark-skinned people of a caste so low that they had no proper right to have emotions. The blood of these people was charmingly full of malaria microbes. The mosquitoes hummed under the nets—and wouldn't bite. Curse it! They could not be made to bite! "They are stubborn as mules," wrote Ross, in agony, to Patrick Manson. But he kept at it. He cajoled the mosquitoes. He pestered the patients. He put them in the hot sun "to bring their flavor out." The mosquitoes kept on humming and remained sniffish. But, eureka! At last he hit on the idea of pouring water over the nets, soaking the nets—also the patients, but that was no matter—and finally the mosquitoes got to work and sucked their fill of Hindu blood. Ronald Ross caught them then, put them gingerly in bottles, then day after day killed them and peeped into their stomachs to see if those malaria microbes they had sucked in with the blood might be growing. They didn’t grow!

He bungled. He was like any tyro searcher—only his innate hastiness made him worse—and he was constantly making momentous discoveries that turned out not to be discoveries at all. But his bunglings had fire in them. To read his letters to Patrick Manson, you would think he had made himself miraculously small and crawled under the lens into that blood among the objects he was learning to spy upon. And what was best, everything was a story to him, no, more than a story, a melodrama. Manson had told him to watch those strange whips that grew out of the crescent malaria germs and made them look like octopuses. In vast excitement he wrote a long letter to Manson, telling of a strange fight between a whip that had shaken itself free, and a white blood cell—a phagocyte. He was a vivid man, was Ronald Ross. "He [Ross called that whip "he"] kept poking the phagocyte in the ribs (!) in different parts of his body, until the phagocyte finally turned and ran off howling . . . the fight between the whip and the phagocyte was wonderful. . . . I shall write a novel on it in the style of the 'Three Musketeers.' " That was the way he kept himself at it and got himself past the first ambushes and disappointments of his ignorance and inexperience. He collected malarious Hindus as a terrier collects rats. He loved them if they were shot full of malaria, he detested them when they got better. He gloried in the wretched Abdul Wahab, a dreadful case. He pounced on Abdul and dragged him from pillar to post. He put fleas on him. He tortured him with mosquitoes. He failed. He kept at it. He wrote to Manson: "Please send me advice. . . ." He missed important truths that lay right under his nose—that yelled to be discovered.

But he was beginning to know just exactly what a malaria parasite looked like—he could spot its weird black grains of pigment, and tell them apart from all of the unknown tiny blobs and bubbles and balloons that drifted before his eyes under his lens. And the insides of the stomachs of mosquitoes? They were becoming as familiar as the insides of his nasty hot quarters!

What an incredible pair of searchers they were! Away in London Patrick Manson kept answering Ross's tangled tortured letters, felt his way and gathered hope from his mixed-up accounts of unimportant experiments. "Let mosquitoes bite people sick with malaria," wrote Manson, "then put those mosquitoes in a bottle of water and let them lay eggs and hatch out grubs. Then give that mosquito-water to people to drink. . . ."

So Ross fed some of this malaria-mosquito soup to Lutchman, his servant, and almost danced with excitement as the man's temperature went up—but it was a false alarm, it wasn't malaria, worse luck. . . . So dragged the dreary days, the months, the years, feeding people mashed-up mosquitoes and writing to Manson: "I have a sort of feeling it will succeed—I feel a kind of religious excitement over it!" But it never succeeded. But he kept at it. He intrigued to get to places where he might find more malaria; he discovered strange new mosquitoes and from their bellies he dredged up unheard-of parasites—that had nothing to do with malaria. He tried everything. He was illogical. He was anti-scientific. He was like Edison combing the world to get proper stuff out of which to make phonograph needles. "There is only one method of solution," he wrote, "that is, by incessant trial and exclusion." He wrote that, while the simple method lay right under his hand, unfelt.

He wrote shrieking poems called "Wraths." He was ordered to Bangalore to try to stop the cholera epidemic, and didn't stop it. He became passionate about the Indian authorities. "I wish I might rub their noses in the filth and disease which they so impotently let fester in Hindustan," Ronald Ross cried. But who can blame him? It was hot there. "I was now forty years old," he wrote, "but, though I was well known in India, both for my sanitary work at Bangalore and for my researches on malaria I received no advancement at all for my pains."

IV

So passed two years, until, in June of 1897 Ronald Ross came back to Secunderabad, to the steamy hospital of Begumpett. The monsoon bringing its cool rain should have already broken, but it had not. A hellish wind blew gritty clouds of dust into the laboratory of Ronald Ross. He wanted to throw his microscope out of the window. Its one remaining eyepiece was cracked, and its metal work was rusted with his sweat. There was the punka, the blessed punka, but he could not start the punka going because it blew his dead mosquitoes away, and in the evening when the choking wind had died, the dust still hid the sun in a dreadful haze. Ronald Ross wrote:

What ails the solitude?

- Is this the judgment day?

The sky is red as blood

- The very rocks decay.

And that relieved him and released him, just as another man might escape by whiskey or by playing bottle-pool, and on the sixteenth of August he decided to begin his work all over, to start, in short, where he had begun in 1895—"only much more thoroughly this time." So he stripped his malaria patient—it was the famous Husein Khan. Under the mosquito net went Husein, for Ronald Ross had found a new kind of mosquito with which to plague this Husein Khan, and in his unscientific classification Ross called this mosquito, simply, a brown mosquito. (For the purposes of historical accuracy, and to be fair to Battista Grassi, I must state that it is not clear where these brown mosquitoes came from. In the early part of his report Ronald Ross says he raised them from the grubs—but a moment later, speaking of a closely related mosquito, he says: "I have failed in finding their grubs also.")

It is no wonder—though lamentable for the purposes of history—that Ronald Ross was mixed up, considering his lone-wolf work and that hot wind and his perpetual failures! Anyway, he took those brown mosquitoes (which may have bitten other beasts, who knows) and loosed them out of their bottles under the net. They sucked the blood of Husein Khan, at a few cents per suck per mosquito, and then once more, one day after another, Ross peeped at the stomachs of those insects.

On the nineteenth of August he had only three of the brown beasts left. He cut one of them up. Hopelessly he began to look at the walls of its stomach, with its pretty, regular cells arranged like stones in a paved road. Mechanically he peered down the tube of his microscope, when suddenly something queer forced itself up into the front of his attention.

What was this? In the midst of the even pavement of the cells of the stomach wall lay a funny circular thing, about a twenty-five-hundredth of an inch its diameter was—here was another! But, curse it! It was hot—he stopped looking. . . .

The next day it was the same. Here, in the wall of the stomach of the next to the last mosquito, four days after it had sucked the blood of the unhappy malarious Husein Khan, here were those same circular outlines—clear—much more distinct  than the outlines of the cells of the stomach, and in each one of these circles was "a cluster of small granules, black as jet!" Here was another of those fantastic things, and another—he counted twelve in all. He yawned. It was hot. That black pigment looked a lot like the black pigment inside of malaria microbes in the blood of human bodies—but it was hot. Ross yawned, and went home for a nap.

than the outlines of the cells of the stomach, and in each one of these circles was "a cluster of small granules, black as jet!" Here was another of those fantastic things, and another—he counted twelve in all. He yawned. It was hot. That black pigment looked a lot like the black pigment inside of malaria microbes in the blood of human bodies—but it was hot. Ross yawned, and went home for a nap.

And as he awoke—so he says in his memoirs—a thought struck him: "Those circles in the wall of the stomach of the mosquito—those circles with their dots of black pigment, they can't be anything else than the malaria parasite, growing there. . . . That black pigment is just like the specks of black pigment in the microbes in the blood of Husein Khan. . . . The longer I wait to kill my mosquitoes after they have sucked his blood, the bigger those circles should grow . . . if they are alive, they must grow!"

Ross fidgeted about—and how he could fidget!—waiting for the next day, that would be the fifth day after his little flock of mosquitoes had fed on Husein under the net. That was the day for the cutting up of the last mosquito of the flock. Came the twenty-first of August. "I killed my last mosquito,” Ronald Ross wrote to Manson, “and rushed at his stomach!"

Yes! Here they were again, those circle cells, one . . . two . . . six . . . twenty of them. . . . They were full of the same jet-black dots. . . . Sure enough! They were bigger than the circles in the mosquito of the day before. . . . They were really growing! They must be the malaria parasites growing! (Though there was no absolutely necessary reason they must be.) But they must be! Those circles with their black dots in the bellies of three measly mosquitoes now kicked Ronald Ross up to heights of exultation. He must write verses!

Oh, million-murdering death.

A million men will save—

Oh, death, where is thy sting?

Thy victory, oh, grave?"

At least that is what Ronald Ross, in those memoirs of his, says he wrote on the night of the day of his first little success. But to Manson, telling the finest details about the circles with their jet-black dots, he only said:

"The hunt is up again. It may be a false scent, but it smells promising."

And in a scientific paper, sent off to England to the British Medical Journal, Ronald Ross wrote gravely like any cool searcher. He wrote admitting he had not taken pains to study his brown mosquitoes carefully. He admitted the jet-black dots might not be malaria parasites at all, but only pigment coming from the blood in the mosquito's gullet. There certainly was need for this caution, for he was not sure where his brown mosquitoes came from: some of them might have sneaked in through a hole in the net—and those intruders might have bitten a bird or beast before they fed on his Hindu patient. It was a most mixed-up business. But he could write poems about saving the lives of a million men!

Such a man was Ronald Ross, mad poet shaking his fist in the face of the malignant Indian sun, celebrating uncertain discoveries with triumphant verses, spreading nets with maybe no holes in them. . . . But you must give him this: he had been lifted up. And, as you will see, it was to the everlasting honor of Ronald Ross that he was exalted by this seemingly so piffling experiment. He clawed his way—and this is one of the major humors of human life!—with unskilled but enthusiastic fingers toward the uncovering of a murderous fact and a complicated fact. A fact you would swear it would take the sure intelligence of some god to uncover.

Then came one of those deplorable interludes. The High Authorities of the Indian Medical Service failed to appreciate him. They sent him off to active duty at doctoring, mere doctoring. Ronald Ross rained telegrams on his Principal Medical Officer. He implored Manson way off there in England. In vain. They packed him off up north, where there were few mosquitoes, where the few he did catch would not bite—it was so cold, where the natives (they were Bhils) were so superstitious and savage they would not let him prick their fingers. All he could do was fish trout and treat cases of itch. How he raved!

V

But Patrick Manson did not fail him, and presently Ross came down from the north, to Calcutta, to a good laboratory, to assistants, to mosquitoes, to as many—for that city was a fine malaria pest-hole!—Hindus with malaria crescents in their blood as any searcher could possibly want. He advertised for helpers. An assorted lot of dark-skinned men came, and of these he chose two. The first, Mahomed Bux, Ronald Ross hired because he had the appearance of a scoundrel, and (said Ross) scoundrels are much more likely to be intelligent. The second assistant Ross chose was Purboona. All we know of that man is that he had the booming name of Purboona, and Purboona lost his chance to become immortal because he vamoosed after his first pay day.

So Ross and Mr. Mahomed Bux set to work to try to find once more the black-dotted circles in the stomachs of mosquitoes. Mr. Mahomed Bux sleuth-footed it about, among the sewers, the drains, the stinking tanks of Calcutta, catching gray mosquitoes and brindled mosquitoes and brown and green dappled-winged ones. They tried all kinds of mosquitoes (within the limits of Ronald Ross's feeble knowledge of the existing kinds). And Mr. Mahomed Bux? He was a howling success. The mosquitoes seemed to like him, they would bite Hindus for this wizard of a Mahomed when Ross could not make them bite at all—Mahomed whispered things to his mosquitoes. . . . And a rascal? No. Mr. Mahomed Bux had just one little weakness—he faithfully got thoroughly drunk once a week on Ganja. But the experiments? They turned out as miserably as Mahomed turned out beautifully, and it was easy for Ross to wonder whether the heat was causing him to see things last year at Begumpett.

Then the God of Gropers came to help Ronald Ross. Birds have malaria. The malaria microbe of birds looks very like the malaria microbe of men. Why not try birds?

So Mr. Mahomed Bux went forth once more and cunningly snared live sparrows and larks and crows. They put them in cages, on beds, with mosquito bar over the cages, and Mahomed slept, with one eye open, on the floor between the beds to keep away the cats.

On St. Patrick's day of the year 1898, Ronald Ross let loose ten gray mosquitoes into a cage containing three larks, and the blood of those larks teemed with the germs of malaria. The ten mosquitoes bit those larks, and filled themselves with lark's blood.

Three days later Ronald Ross could shout: "The microbe of the malaria of birds grows in the wall of the stomach of the gray mosquito—just as the human microbe grew in the wall of the stomach of the brown spot-winged mosquito."

Then he wrote to Patrick Manson. This lunatic Ross became for a moment himself a malaria microbe! That night he wrote these strange words to Patrick Manson:

"I find that I exist constantly in three out of four mosquitoes fed on bird-malaria parasites, and that I increase regularly in size from about a seven-thousandth of an inch after about thirty hours to about one seven-hundredth of an inch after about eighty-five hours. . . . I find myself in large numbers in about one out of two mosquitoes fed on two crows with blood parasites. . . ."

He thought he was himself a circle with those jet-black dots. . . .

"What an ass I have been not to follow your advice before and work with birds!" Ross wrote to Manson. Heaven knows what Ronald Ross would have discovered without that persistent Patrick Manson.

You would think that such a man as Ross, wild as the maddest of hatters, topsy-turvy as the dream of a hasheesh-eater, you would swear, I say, that he could do no accurate experiments. Wrong! For presently he was up to his ears in an experiment Pasteur would have been proud to do.

Mr. Mahomed Bux brought in three sparrows, and one of these sparrows was perfectly healthy, with no malaria microbes in its blood; the second had a few; but the third sparrow was very sick—his blood swarmed with the black-dotted germs. Ross took these three birds and put each one in a separate cage, mosquito-proof. Then the artful Mahomed took a brood of she-mosquitoes, clean, raised from the grubs, free of all suspicion of malaria. He divided this flock up into three little flocks, he whispered Hindustani words of encouragement to them. Into each cage, with its sparrow, he let loose a flock of these mosquitoes.

Marvelous! Not a mosquito who sucked the blood of the healthy sparrow showed those dotted circles in her stomach. The insects who had bitten the mildly sick bird had a few. And Ronald Ross, peeping through his lens at the stomachs of the mosquitoes who had bitten the very sick sparrow—found their gullets fairly polka-dotted with the jet-black pigmented circles!

Day after day Ross killed and cut up one after another of the last set of mosquitoes. Day after day, he watched those circles swelling, growing—there was no doubt about it now; they began to look like warts sticking out of the wall of the stomach. And he watched weird things happening in those warts. Little bright colored grains multiplied in them, "like bullets in a bag." Were these young malaria microbes? Then where did they go from here? How did they get into new healthy birds? Did they, indeed, get from mosquitoes into other birds?

Excitedly Ronald Ross wrote to Patrick Manson: "Well, the theory is proved, the mosquito theory is a fact." Which of course it wasn't, but that was the way Ronald Ross encouraged himself. There was another regrettable interlude, in which the unseen hand of his incurable restless dissatisfaction took him by the throat, and dragged him away up north to Darjeeling, to the hills that make giant's steps up to the white Himalayas, but of this interlude we shall not speak, for it was lamentable, this restlessness of Ronald Ross, with the final simple experiment fairly yelling to be done. . . .

But by the beginning of June he was back at his birds in Calcutta—it was more than 100 degrees in his laboratory— and he was asking: "Where do the malaria microbes go from the circles that grow into those big warts in the stomach wall of the mosquito?"

They went, those microbes, to the spit-gland of those mosquitoes!

Squinting through his lens at a wart on the wall of the stomach of a she-mosquito, seven days after she had made a meal from the blood of a malarious bird, Ronald Ross saw that wart burst open! He saw a great regiment of weird spindle-shaped threads march out of that wart. He watched them swarm through the whole body of that she-mosquito. He pawed around in countless she-mosquitoes who had fed on malarious birds. He watched other circles grow into warts, get ripe, burst, shoot out those spindles. He pried through his lens at the "million things that go to make up a mosquito"—he hadn’t the faintest notion what to call most of them—until one day, strangest of acts of malignant nature, he saw those regiments of spindle-threads, which had teemed in the body of the mosquito, march to her spit-gland.

In that spit-gland, feebly, lazily moving in it, but swarming in such myriads that they made it quiver, almost, under his lens, were those regiments and armies of spindle-shaped threads, hopeful valiant young microbes of malaria, ready to march up the tube to the mosquito's stinger. . . .

"It's by the bite mosquitoes carry malaria then," Ross whispered—he whispered it because that was contrary to the theory of his scientific father, Patrick Manson. "It is all nonsense that birds—or people either—get malaria by drinking dead mosquitoes, or by inhaling the dust of mosquitoes. . . ." Ronald Ross had always been loyal to Patrick Manson. But now! Never has there been a finer instance of wrong theories leading a microbe hunter to unsuspected facts. But now! Ronald Ross needed no help. He was a searcher.

"It's by the bite!" shouted Ronald Ross, so, on the twenty-fifth day of June in 1898, Mr. Mahomed Bux brought in three perfectly healthy sparrows—fine sparrows with not a single microbe of malaria in their blood. That night, and night after night after that night, with Ronald Ross watching, Mr. Mahomed Bux let into the cage with those healthy sparrows a flock of poisonous she-mosquitoes who had fed on sick birds. . . . And Ronald Ross, fidgety as a father waiting news of his first-born child, biting his mustache, sweating, and sweating more yet because he used up so much of himself cursing at his sweat—Ross watched those messengers of death bite the healthy sparrows. . . .

On the ninth of July Ross wrote to Patrick Manson: "All three birds, perfectly healthy before, are now simply swarming with proteosoma." (Proteosoma are the malarial parasites of birds.)

Now Ronald Ross did anything but live remotely on his mountain top. He wrote this to Manson, he wired it to Manson, he wrote it to Paris to old Alphonse Laveran, the discoverer of the malaria microbe; he sent papers to one scientific journal and two medical journals about it; he told everybody in Calcutta about it; he bragged about it—in short, this Ronald Ross was like a boy who had just made his first kite finding that the kite could really fly. He went wild—and then (it is too bad!) he collapsed. Patrick Manson went to Edinburgh and told the doctors of the great medical congress about the miracle of the sojourn and the growing and the meanderings of the malaria microbes in the bodies of gray she-mosquitoes: he described how his protégé, Ronald Ross, alone, obscure, laughed at, but tenacious, had tracked the germ of malaria from the blood of a bird through the belly and body of she-mosquitoes to their dangerous position in her stinger, ready to be shot into the next bird she bit.

The learned doctors gaped. Then Patrick Manson read out a telegram from Ronald Ross. It was the final proof: the bite of a malarial mosquito had given a healthy bird malaria! The congress—this is the custom of congresses—permitted itself a dignified furore, and passed a resolution congratulating this unknown Major Ronald Ross on his "Great and Epoch-Making Discovery." The congress—it is the habit of congresses—believed that what is true for birds goes for men too. The congress—men in the mass are ever uncritical—thought that this meant malaria would be wiped out from to-morrow on and forever—for what is simpler than to kill mosquitoes? So that congress permitted itself a furore.

But Patrick Manson was not so sure: "One can object that the facts determined for birds do not hold, necessarily, for men." He was right. There was the rub. This was what Ronald Ross seemed to forget: that nature is everlastingly full of surprises and annoying exceptions, and if there are laws and rules for the movements of the planets, there may be absolutely no apparent rime and less reason for the meanderings of the microbes of malaria. . . . Searchers, the best of them, still do no more than scratch the surface of the most amazing mysteries, all they can do (yet!) to find truth about microbes is to hunt, hunt endlessly. . . . There are no laws!

So Patrick Manson was stern with Ronald Ross. This nervous man, feeling he could stand this cursed India not one moment longer, must stand it months longer, years longer! He had made a brilliant beginning, but only a beginning. He must keep on, if not for science, or for himself, then for England! For England! And in October Manson wrote him: "I hear Koch has failed with the mosquito in Italy, so you have time to grab the discovery for England."

But Ronald Ross—alas—could not grab that discovery of human malaria, not for science, nor humanity, nor for England—nor (what was worst) for himself. He had come to the end of his rope. And among all microbe hunters, there is for me no more tortured man than this same Ronald Ross. There have been searchers who have failed—they have kept on hunting with the naturalness of ducks swimming; there have been searchers who have succeeded gloriously—but they were hunters born, and they kept on hunting in spite of the seductions of glory. But Ross! Here was a man who could only do patient experiments—with a tragic impatience, in agony, against the clamoring of his instincts that yelled against the priceless loneliness that is the one condition for all true searching. He had visions of himself at the head of important committees, and you can feel his dreams of medals and banquets and the hosannahs of multitudes. . . .

He must grab the discovery for England. He tried gray mosquitoes and green and brown and dappled-winged mosquitoes on Hindus rotten with malaria—but it was no go! He became sleepless and lost eleven pounds. He forgot things. He could not repeat even those first crude experiments at Secunderababad.

And yet—all honor to Ronald Ross. He did marvelous things in spite of himself. It was his travail that helped the learned, the expert, the indignant Battista Grassi to do those clean superb experiments that must end in wiping malaria from the earth.

VI

You might know Giovanni Battista Grassi would be the man to do what Ronald Ross had not quite succeeded in bringing off. He had been educated for a doctor, at Pavia where that glittering Spallanzani had held forth amid applause a hundred years before. Grassi had been educated for a doctor (Heaven knows why) because he had no sooner got his license than he set himself up in business as a searcher in zoölogy. With a certain amount of sniffishness he always insisted: "I am a zoologo—not a medico!" Deliberate as a glacier, precise as a ship's chronometer, he started finding answers to the puzzles of nature. Correct answers! His works were pronounced classics right after he published them—but it was his habit not to publish them for years after he started to do them. He made known the secret comings and goings of the Society of the White Ants—not only this, but he discovered microbes that plagued and preyed upon these white ants. He knew more than any man in the world about eels—and you may believe it took a searcher with the insight of a Spallanzani to trace out the weird and romantic changes that eels undergo to fulfill their destiny as eels. Grassi was not strong. He had abominable eyesight. He was full of an argumentative petulance. He was a contradictory combination of a man too modest to want his picture in the papers but bawling at the same time for the last jot and tittle of credit for everything that he did. And he did everything. Already, when he was only twenty-nine, before Ross had dreamt of becoming a searcher, Battista Grassi was a professor, and had published his famous monograph upon the Chaetognatha (I do not know what they are!).

Before Ronald Ross knew that anybody had ever thought of mosquitoes carrying malaria, Grassi had had the idea, had taken a whirl at experiments on it, but had used the wrong mosquito, and failed. But that failure started ideas stewing in his head while he worked at other things—and how he worked! Grassi detested people who didn’t work. "Mankind," he said, "is composed of those who work, those who pretend to work, and those who do neither." He was ready to admit that he belonged in the first class, and it is entirely certain that he did belong there.

In 1898, the year of the triumph of Ronald Ross, Grassi, knowing nothing of Ross, never having heard of Ross, went back at malaria again. "Malaria is the worst problem Italy has to face! It desolates our richest farms! It attacks millions in our lush lowlands! Why don’t you solve that problem?" So the politicians, to Battista Grassi. Then too, the air was full of whispers of the possibility that I don't know how many different diseases might be carried from man to man by insects. There was that famous work of Theobald Smith, and Grassi had an immense respect for Theobald Smith. But what probably finally set Grassi working at malaria—you must remember he was a very patriotic and jealous man—was the arrival of Robert Koch. Dean of the microbe hunters of the world, Tsar of Science (his crown was only a little battered) Koch had come to Italy to prove that mosquitoes carry malaria from man to man.

Koch was an extremely grumpy, quiet, and restless man now; sad because of the affair of his consumption cure (which had killed a considerable number of people); restless after the scandal of his divorce from Emmy Fraatz. So Koch went from one end of the world to the other, offering to conquer plagues but not quite succeeding, trying to find happiness and not quite reaching it. His touch faltered a little. . . . And now Koch met Battista Grassi, and Grassi said to Robert Koch:

"There are places in Italy where mosquitoes are absolutely pestiferous—but there is no malaria at all in those places!"

"Well—what of it?"

"Right off, that would make you think mosquitoes had nothing to do with malaria," said Battista Grassi.

"So?”. . . Koch was enough to throw cold water on any logic!

"Yes—but here is the point," persisted Grassi, "I have not found a single place where there is malaria—where there aren't mosquitoes too!"

"What of that?"

"This of that!" shouted Battista Grassi. "Either malaria is carried by one special particular blood-sucking mosquito, out of the twenty or forty kinds of mosquitoes in Italy—or it isn't carried by mosquitoes at all!"

"Hrrrm-p,” said Koch.

So Grassi made no hit with Robert Koch, and so Koch and Grassi went their two ways, Grassi muttering to himself: "Mosquitoes—without malaria . . . but never malaria—without mosquitoes! That means one special kind of mosquito! I must discover the suspect. . . ."

That was the homely reasoning of Battista Grassi. He compared himself to a village policeman trying to discover the criminal in a village murder. "You wouldn’t examine the whole population of a thousand people one by one!" muttered Grassi. "You would try to locate the suspicious rogues first. . . .”

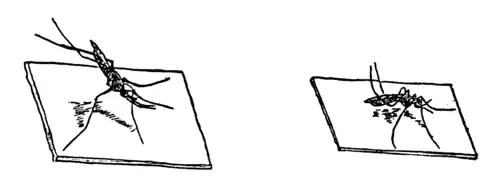

His lectures for the year 1898 at the University of Rome over, he was a conscientious man who always gave more lectures than the law demanded, he needed a rest, and on the 15th of July he took it. Armed with sundry fat test-tubes and a notebook, he sallied out from Rome to those low hot places and marshy desolations where no man but an idiot would go for a vacation. Unlike Ross, this Grassi was a mosquito expert besides everything else that he was. His eyes—so red-rimmed and weak—were exceedingly sharp at spotting every difference between the thirty-odd different kinds of mosquitoes that he met. He went around with the fat test-tube in his hand, his ear cocked for buzzes. The buzz dies away as the mosquito lights. She has lit in an impossible place. Or she has lit in a disgusting place. No matter, Battista Grassi is up behind her, pounces on her, claps his fat test-tube over her, puts a grubby thumb over the mouth of the test-tube, paws over his prize and pulls her apart, scrawls little cramped pot-hooks in his notebook. That was Battista Grassi, up and down and around the nastiest places in Italy all that summer.

So it was he cleared a dozen or twenty different mosquitoes of the suspicion of the crime of malaria—he was always finding these beasts in places where there was no malaria. He ruled out two dozen different kinds of gray mosquitoes and brindled mosquitoes, that he found anywhere—in saloons and bedrooms and the sacristies of cathedrals, biting babies and nuns and drunkards. "You are innocent!" shouted Battista Grassi at these mosquitoes. "For where you are none of these nuns or babies or drunkards suffers from malaria!"

You will grant this was a most outlandish microbe hunting of Grassi's. He went around making a nuisance of himself. He insinuated himself into the already sufficiently annoyed families of those hot malarious towns. He snooped annoyingly into the affairs of these annoyed families: "Is there malaria in your house? . . . Has there ever been malaria in your house? . . . How many have never had malaria in your house . . . how many mosquito bites did your sick baby have last week? . . . What kind of mosquitoes bit him?" He was utterly without a sense of humor. And he was annoying.

"No," the indignant head of the house might tell him, "we suffer from malaria—but we are not bothered by mosquitoes!" Battista Grassi would never take his word for that. He snouted into pails and old crocks in the back yards. He peered beneath tables and behind sacred images and under beds. He even discovered mosquitoes hiding in shoes under those beds. . . .

So it was—it is most fantastical—that Battista Grassi went more than two-thirds of the way to solving this puzzle of how malaria gets from sick men to healthy ones before he had ever made a single experiment in his laboratory! For, everywhere where there was malaria, there were mosquitoes. And such mosquitoes! They were certainly a very special definite sort of blood-sucking mosquito Grassi found.

"Zan-za-ro-ne, we call that kind of mosquito," the householders told him.

Always, where the "zan-za-ro-ne" buzzed, there Grassi found deep flushed faces on rumpled beds, or faces with chattering teeth going towards those beds. Always where that special and definite mosquito sang at twilight, Grassi found fields waiting for some one to till them, and from the houses of the little villages that sat in these fields, he saw processions emerging, and long black boxes. . . .

There was no mistaking this mosquito, zanzarone, once you had spotted her; she was a frivolous gnat that flew up from the marshes towards the lights of the towns; she was an elegant mosquito proud of four dark spots on her light brown wings; she was not a too dignified insect who sat in an odd way with the tail-end of her body sticking up in the air [that was one way he could spot her, for the Culex mosquitoes drooped their tails]; she was a brave blood-sucker who thought: "The bigger they are the more blood I get out of them!" So zanzarone preferred horses to men and men to rabbits. That was zanzarone, and the naturalists had given her the name Anopheles claviger many years before. Anopheles claviger! This became the slogan of Battista Grassi. You can see him, shuffling along behind lovers in the dusk, making fists of his fingers to keep himself from pouncing on the zanzarone who made meals off their regardless necks. . . . You can see this Grassi, sitting in a stagecoach with no springs, oblivious to bumps, deaf to the chatter of his fellow-passengers, with absent eyes counting the Anopheles claviger he had discovered—with delight—riding on the ceiling of the wagon in which he journeyed from one utterly terrible little malarious village to another still more cursed.

"I'll try them on myself!" Grassi cried. He went up north to his home in Rovellasca. He taught boys how to spot the anopheles mosquito. The boys brought boxes full of these she-zanzarone from towns where malaria rages. Grassi took these boxes to his bedroom, put on his night shirt, opened the boxes, crawled into bed—but curse it! not one of the zanzarone bit him. Instead they flew out of his room and bit Grassi's mother, "fortunately without ill effect!"

Then Grassi went back to Rome to his lectures, and on September 28th of 1898, before ever he had done a single serious experiment, he read his paper before the famous and ancient Academy of the Lincei: "It is the anopheles mosquito that carries malaria if any mosquito carries malaria . . ." And he told them he was suspicious of two other brands of mosquitoes—but that was absolutely all, out of the thirty or forty different tribes that infected the low places of Italy.

Then came an exciting autumn for Battista Grassi and an entertaining autumn for the wits of Rome, and a most important autumn for mankind. Besides all that it was a most itchy autumn for Mr. Sola, who for six years had been a patient of Dr. Bastianelli in the Hospital of the Holy Spirit, high up on the top floor of this hospital that sat on a high hill of Rome. Here zanzarone never came. Here nobody ever got malaria. Here was the place for experiments. And here was Mr. Sola, who had never had malaria, every twist and turn of whose health Dr. Bastianelli knew, who told Battista Grassi that he would not mind being shut up with three different brands of hungry she-mosquitoes every night for a month.

Grassi and Bignami and Bastianelli started off, strangely enough, with those two minor mosquito suspects—those two culexes that Grassi had discovered always hanging around malarious places along with the zanzarone. . . . They tortured Mr. Sola each night with hundreds of these mosquitoes. They shut poor Mr. Sola up in that room with those devils and turned off the light. . . .

Nothing happened. Sola was a tough man. Sola showed not a sign of malaria.

(It is not clear why Grassi did not start off by loosing his zanzarone at this Mr. Sola.)

Maybe it was because Robert Koch had laughed publicly at this idea of the zanzarone—Grassi does admit that discourse aged him.

But, one fine morning, Grassi hurried out of Rome to Moletta and came back with a couple of little bottles in which buzzed ten fine female anopheles mosquitoes. That night Mr. Sola had a particularly itchy time of it. Ten days later this stoical old gentleman shook horribly with a chill, his body temperature shot up into a high fever—and his blood swarmed with the microbes of malaria.

"The rest of the history of Sola's case has no interest for us," wrote Grassi, "but it is now certain that mosquitoes can carry malaria, to a place where there are no mosquitoes in nature, to a place where no case of malaria has ever occurred, to a man who has never had malaria—Mr. Sola!"

Over the country went Grassi once more, chasing zanzarone, hoarding zanzarone: in his laboratory he tenderly raised zanzarone on winter-melons and sugar-water; and in the top of the hospital of the Holy Spirit, in those high mosquito-proof rooms, Grassi and Bastianelli (to say nothing of another assistant, Bignami) loosed zanzarone into the bedrooms of people who had never had malaria—and so gave them malaria.

It was an itchy autumn and an exciting one. The newspapers became sarcastic and hinted that the blood of these poor human experimental animals would be on the heads of these three conspirators. But Grassi said: to the devil with the newspapers, he cheered when his human animals got sick, he gave them doses of quinine as soon as he was sure his zanzarone had given them malaria, and then "their histories had no further interest for him."

By now Grassi had read of those experiments of Ronald Ross with birds. "Pretty crude stuff!" thought this expert Grassi, but when he came to look for those strange doings of the circles and warts and spindle-shaped threads in the stomachs and saliva-glands of his she-anopheles, he found that Ronald Ross was exactly right! The microbe of human malaria in the body of his zanzarone did exactly the same things the microbe of bird malaria had done in the bodies of those mosquitoes Ronald Ross hadn't known the names of. Grassi didn't waste too much time praising Ronald Ross, who, Heaven knows, deserved praise, needed praise, and above all wanted praise. Not Grassi!

"By following my own way I have discovered that a special mosquito carried human malaria!" he cried, and then he set out—"It is with great regret I do this," he explained—to demolish Robert Koch. Koch had been fumbling and muddling. Koch thought malaria went from man to man just as Texas fever traveled from cow to cow. Koch believed baby mosquitoes inherited malaria from their mothers, bit people, and so infected them. And Koch had sniffed at the zanzarone.

So Grassi raised baby zanzarone. He let them hatch out in a room, and every evening in this room, for four months, sat this Battista Grassi with six or seven of his friends. What friends he must have had! For every evening they sat there in the dusk, barelegged with their trousers rolled up to their knees, bare-armed with their shirt sleeves rolled up to their elbows. Some of these friends, whom the anopheles relished particularly, were stabbed every night fifty or sixty times! So Grassi demolished Robert Koch, and so he proved his point, because, though the baby anopheles were children of mother mosquitoes who came from the most pestiferous malaria holes in Italy, not one of Grassi's friends had a sign of malaria!

"It is not the mosquito's children, but only the mosquito who herself bites a malaria sufferer—it is only that mosquito who can give malaria to healthy people!" cried Grassi.

Grassi was as persistent as Ronald Ross had been erratic. He plugged up every little hole in his theory that anopheles is the one special and particular mosquito to bring malaria to men. By a hundred air-tight experiments he proved the malaria of birds could not be carried by the mosquitoes who brought it to men and that the malaria of men could never be strewn abroad by the mosquitoes who brought it to birds. Nothing was too much trouble for this Battista Grassi! He knew as much about the habits and customs and traditions of those zanzarone as if he himself were a mosquito and the king and ruler of mosquitoes. . . .

VII

What is more, Battista Grassi was a practical man, and as I have said, an excessively patriotic man. He wanted to see his discovery do well by Italy, for he loved his Italy faithfully and violently. His experiments were no sooner finished, the last good strong nail was no sooner driven into the house of his case against the anopheles, than he began telling people, and writing in newspapers, and preaching—you might almost say he went about, bellowing till he bored everybody:

"Keep away the zanzarone and in a few years Italy will be free from malaria!"

He became a fanatic on the best ways to kill anopheles: he was indignant (that man had no sense of humor!) because townspeople insisted on strolling through their streets in the dusk. "How can you be so foolish as to walk in the twilight?" Grassi asked them. "That is the very time when the malaria mosquito is waiting for you."

He was the very type of the silly sanitarian. "Don't go out in the warm evenings," he told every one, "unless you wear heavy cotton gloves and veils!" (Imagine young Italians making love in heavy cotton gloves and veils.) So there was a good deal of sniggering at this professor who had become a violent missionary against the zanzarone.

But Battista Grassi was a practical man! "One family, staying free from the tortures of malaria—that would be worth ten years of preaching—I’ll have to show them!" he muttered. So, in 1900, after his grinding experiments of 1898 and '99, this tough man set out to "show them." He went down into the worst malaria region of Italy, along the railroad line that ran through the plain of Capaccio. It was high summer. It was deadly summer there, and every summer the poor wretches of railroad workers, miserable farmers whose blood was gutted by the malaria poison, would leave that plain, at the cost of their jobs, at the cost of food, at the risk of starvation—to the hills to flee the malaria. And every summer from the swamps at twilight swarmed the malignant hosts of female zanzarone; at each hot dusk they made their meals and did their murders, and in the night, bellies full of blood, they sang back to their marshes, to marry and lay eggs and hatch out thousands more of their kind.

In the summer of 1900 Battista Grassi went to the plain of Capaccio. The hot days were just beginning, the anopheles were on the march. In the windows and on the doors of ten little houses of station-masters and employees of the railroad Grassi put up wire screens, so fine-meshed and so perfect that the slickest and the slightest of the zanzarone could not slip through them. Then Grassi, armed with authority from the officials of the railroad, supplied with money by the Queen of Italy, became a task-master, a Pharaoh with lashes. One hundred and twelve souls—railroad men and their families—became the experimental animals of Battista Grassi and had to be careful to do as he told them. They had to stay indoors in the beautiful but dangerous twilight. Careless of death—especially unseen death—as all healthy human beings are careless, these one hundred and twelve Italians had to take precautions, to avoid the stabs of mosquitoes. Grassi had the devil of a time with them. Grassi scolded them. Grassi kept them inside those screens by giving them prizes of money. Grassi set them an indignant example by coming down to Albanella, most deadly place of all, and sleeping two nights a week behind those screens.

All around those screen-protected station houses the zanzarone swarmed in humming thousands—it was a frightful year for mosquitoes. Into the un-screened neighboring station houses (there were four hundred and fifteen wretches living in those houses), the zanzarone swooped and sought their prey. Almost to a man, woman, and child, those four hundred and fifteen men, women and children fell sick with the malaria.

And of those one hundred and twelve prisoners behind the screens at night? They were rained on during the day, they breathed that air that for a thousand years the wisest men were sure was the cause of malaria, they fell asleep at twilight, they did all of the things the most eminent physicians had always said it was dangerous to do, but in the dangerous evenings they stayed behind screens—and only five of them got the malaria during all that summer. Mild cases these were, too, maybe only relapses from the year before, said Grassi.

"In the so-much-feared station of Albanella, from which for years so many coffins had been carried, one could live as healthily as in the healthiest spot in Italy!" cried Grassi.

VIII

Such was the fight of Ronald Ross and Battista Grassi against the assassins of the red blood corpuscles, the sappers of vigorous life, the destroyer of men, the chief scourge of the lands of the South—the microbe of malaria. There were aftermaths of this fight, some of them too long to tell, and some too painful. There were good aftermaths and bad ones. There are fertile fields now, and healthy babies, in Italy and Africa and India and America, where once the hum of the anopheles brought thin blood and chattering teeth, brought desolate land and death.

There is the Panama Canal. . . .

Then there is Sir Ronald Ross, who was—as once he hoped and dreamed—given enthusiastic banquets.

There is Ronald Ross who got the Nobel Prize of seven thousand eight hundred and eighty pounds sterling for his discovery of how the gray mosquito carries malaria to birds. . . .

There is Battista Grassi who didn't get the Nobel Prize, and is now unknown, except in Italy, where they huzzahed for him and made him a Senator (he never missed a meeting of that Senate to within a year of his death).

All these are, for the most part, good, even if some of them are slightly ironical aftermaths.

Then there is Ronald Ross, who had learned the hard game of searching while he made his discovery about the gray mosquito—you would say his best years of work were just beginning—there is Ronald Ross, insinuating Grassi was a thief, hinting that Grassi was a charlatan, saying Grassi had added almost nothing to the proof that mosquitoes carry malaria to men!

There was Grassi—justifiably purple with indignation, writing violent papers in reply. . . . You cannot blame him! But why will such searchers scuffle, when there are so many things left to find? You would think—of course it would be so in a novel—that they could have ignored each other, or could have said: "The facts of science are greater than the little men who find those facts!"—and then have gone on searching, and saving.

For the fight has only just begun. The day I finish this tale, it is twenty-five years after the perfect experiment of Grassi, comes this news item from Tokio—it is stuck away down in a corner of an inside page of a newspaper:

"The population of the Ryukyu Islands, which lie between Japan and Formosa, is rapidly dying off. . . . Malaria is blamed principally. In eight villages of the Yaeyama group . . . not a single baby has been born for the last thirty years. In Nozoko village . . . one sick old woman was the only inhabitant. . . ."