Material Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 7

The two most important forms of dwelling of the Iglulik Eskimos are the snow house and the tent: in that period of autumn before the snow becomes good enough for house building, whereas it is so cold that living in a tent is unpleasant, various dwellings are used which may be grouped under the Eskimo name of qarmat; these are also used occasionally late in spring.

The Iglulik Eskimos do not know permanent winter houses. It is true that here and there in the country there are numerous ruins of such habitations; but they date, as shown elsewhere,[1] from an earlier, now extinct Eskimo culture, the Thule culture; the Iglulik Eskimos themselves ascribe these ruins to another nation, the Tunit, who inhabited the country before them. On Southampton Island the Sadlermiut used such houses right up to the time when they died out in 1903.

The snow house (iglo) and the building of snow houses have been described very frequently in Arctic literature; there is hardly any traveller to the Central regions who has not given a description of this marvel of Eskimo technique which, in a snow storm at a temperature of –40° or –50° C. can, in the course of an hour, create a house in which one may live warmly and comfortably while storm and frost rage outside. Without the snow house, winter travelling in these regions would be practically impossible; that the earlier discoverers up there were so immobile in winter is principally due to the fact that they had not learned to build snow houses.

But if the main features of the construction and erection of snow houses are well enough known, there may be various details worthy of observation, just as there may be local variations among the different tribes. On account of the fundamental importance of the snow house I will therefore describe, from my own observations, the building and erection of the snow house among the Iglulik Eskimos.

When building a snow house, the first thing to do is to look for a snow-bank with sufficiently deep, firm and homogeneous snow;

the bank should preferably be so deep (about half a metre) that the blocks can be cut vertically out of it. In particular, the snow must be uniform in consistence, as otherwise the blocks will easily break; snow that is too loose cannot be used, and too hard snow is also avoided as it is difficult to work with.

For the purpose of examining the nature of the snow they use the snow-probe (aputsiuk),[2] a thin rod of wood, bone or antler with a handle and a ferrule on the end. Fig. 72 c (Repulse Bay) has a handle of wood, in which is inserted a four-sided rod of wood having at the end a ferrule of antler held on by bone rivets; its length is 81 cm. A snow-probe from the Aivilingmiut on Southampton Island has a head of wood, 5 cm in diameter, rounded above and flat underneath, a rather heavier, four-sided wooden rod (1.7 cm thick), which at the end has a heavy, rounded-square ferrule of antler; length 84 cm. With a slight pressure of the hand the snow-probe is pushed down through the snow, and the Eskimo can feel the nature of it by the resistance met with. Often they use no special snow-probe but merely a ramrod or the ice-hunting harpoon; in this case a small lump of wet snow is usually stuck on the end, this freezes and thus acts as a substitute for the ferrule.

The snow having been found satisfactory, a start may be made immediately in cutting out blocks; often a layer of looser snow must first be shovelled off before cutting can commence. The most important implement in snow-house building is the snow-knife (pána). Nowadays they use single-edged, steel knives of European manufacture, but they always put the handle on themselves; it must be long enough to be gripped with two hands, must be fairly thin, with rounded edges so that it does not meet with much resistance from the snow, and must have a knob at the end to act as a stop for the hand; this knob is sometimes a separate piece of ivory lashed on, sometimes a part of the wooden handle itself.

Fig. 73 a (Itibdjeriang) is a modern snow-knife with a large, single-edged, European, iron blade and a wooden handle of the typical form; at the joint between blade and handle there is a reinforcement of musk-ox horn; 50 cm long; the thickness of the handle increases evenly to 1.6 cm at the rear end. A snow-knife from Ponds Inlet is 45 cm long, the blade accounting for 20 cm of this; the thickness of the handle grows from 1.0 cm near the blade to 1.7 at the end. Like the foregoing the blade is wedged into the handle and fastened with rivets. At the middle of the front edge of the handle there is a small projection; a unilateral knob only at the end of the handle. A third snow-knife is 37 cm long, of which the blade measures 16; the wooden handle has a unilateral knob; the blade is straight, wide, single-edged; on both sides of the fore end of the handle there is an iron mounting to strengthen it.

Fig. 73 b (Iglulingmiut, Ponds Inlet) is a sheath for a snow-knife, consisting of a piece of sealskin; in one corner a sealskin thong, 31 cm long, is tied on for suspension purposes. The length is 50 cm, the width at the top 10, at the bottom 5 cm.

The earlier form of snow-knife was of ivory, fairly slender. with a knob tied on to the handle. One of these is shown on fig. 74 a, an old specimen found at Pingerqalik; it is 30 cm long, 1.6 cm thick at the handle; similar snow-knives are figured by Parry[3] and Hall.[4] Fig. 74 b (found at Amitsoq) is a slender, thin, snow-knife blade of ivory, 37 cm long; the handle end is cut off square with seven holes

for fastening on the handle; the blade and handle have run smoothly into each other; greatest thickness 0.9 cm. Boas[5] figures a model of a similar slender snow-knife with a blade of ivory fastened on to a wooden handle. The broad form of snow-knife with one or two shoulders, figured in several places by Boas,[6] seems to be connected with the Thule culture.

Having found a snow-bank of suitable size and kind, preferably with a slightly sloping surface, the cutting out of the snow blocks commences. Two parallel scratches are made in the snow, corresponding to the length of a snow block, 60–70 cm, and the first blocks are cut out of the mass of snow between these; the first one is triangular-prismatic and must be thrown aside; but as soon as this has been removed and a vertical wall has been obtained to commence with, the blocks themselves can be cut out. The snow-knife is run backwards and forwards at the ends of the block in order to prevent the snow from binding; the back-face is formed

Image missingFig. 75.Snow house building.

by sticking the knife down deeply at the back several times, the bottom-face is formed by a single cut, and the block is loosened by a gentle kick with the foot. Most frequently the block is cut on a slight curve, the side facing the worker being a little concave and is intended to face the inside of the house. When a block is loose, it is lifted up and the next one is cut. Not until about ten blocks have been cut does the building of the house begin. By means of the ice-hunting harpoon, the snow-knife or other implement, a circle is often described on the surface of the snow-drift to indicate the size of the house; more frequently, however, building is commenced without it. The first blocks are placed in a circle, leaning slightly inwards, resting against each other, the adjoining faces being trimmed to fit. This circle is so arranged that the passage from which the first row of blocks was cut may be used as the doorway to the house when it is finished; owing to the direction of the wind this doorway should preferably face the south. The following blocks are then cut out from the snow inside the circle as long there is sufficient snow: often there is enough, sometimes so much, indeed, that a ledge can be allowed to remain and form the platform of the house. After the first line of blocks has been set it is cut so that it forms a spiral, ascending from right to left when seen from the inside of the house. Building then continues, the blocks continuing the spiral line; the builder lifts up the block with both hands and sets it on the underlayer; with the snow knife in his right hand he cuts the adjoining faces to fit while pushing the new block into place with his left.[7] Every new row inclines more and more inwards than the preceding one; each new block is supported by obliquely cut faces — one that of the preceding block and one underneath; the uppermost blocks

Fig. 76.Roof construction of snow house.

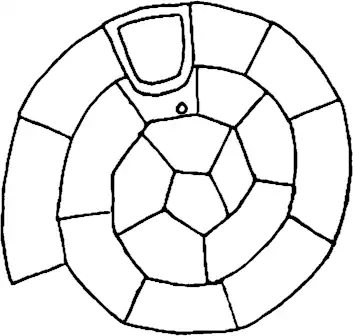

lie almost horizontally but nevertheless rest firmly and securely. The top block is pushed vertically up through the hole and cut above the hole into the requisite shape to fit it, whereafter it is let down into the hole. The roof construction of a snow house at Itibdjeriang is shown in fig. 76.

Fig. 76.Roof construction of snow house.

lie almost horizontally but nevertheless rest firmly and securely. The top block is pushed vertically up through the hole and cut above the hole into the requisite shape to fit it, whereafter it is let down into the hole. The roof construction of a snow house at Itibdjeriang is shown in fig. 76.

The size of the blocks depends upon the nature of the snow; if it is good and firm, the size is 60–80 cm long, 40–50 cm high and 15–20 cm thick; if the snow is very soft or poor. they must be made smaller. For an ordinary snow house about 3 m in diameter about 35 blocks are used.

If there is only one man to build a house with a diameter of about 3 m. the erection itself takes about 1½ hours; if there are two men, so that one can cut the blocks and hand them to the builder. it can be done in an hour, and in forty to fifty minutes when conditions are very favourable. There are men, however, who can build especially quickly; an old Aivilik, Aqaut, once built a snow house himself, big enough for four people, in 26 minutes; but this is the exception. When building large snow houses, two men can take part in the building together, each beginning his spiral at different places and their spirals then run between each other and form the house.

When the building of the house is finished there is still a lot of lighter work to do before it is habitable: holes between the blocks are to be plugged with loose snow or, if they are large, with small blocks cut to fit; the joints are tightened by cutting off the upper, outer edge of the blocks and pressing the snow into the crack with the mitten. If it is a snow house that is to be used for some time as a dwelling, loose snow is shovelled up over it with the snow shovel (puarqit), an important implement, which is always taken along on sledge journeys. Fig. 72 b (Iglulik) is a snow shovel, made of three boards tied together, edge to edge, with sinew-tread; at the bottom is an edging of antler, likewise fastened on with sinew-thread; the blade is strengthened across the top by a small piece of wood; the hand loop is of seal thong; 80 cm long, 29 cm wide. Fig. 72 a (Aivilingmiut) consists of a triangular frame of antler, a blade consisting of two pieces of bearded-seal skin sewn together and a handle of antler; in the frame at the top a hand-loop of antler is inserted and fastened by iron pegs; the various parts are held together with strips of copper, sinew-thread and iron nails; length 86 cm, of which the handle measures 42 cm; breadth 32 cm. A small, crude snow shovel from Iglulik is 63 cm long, 30 cm wide; it consists of three boards tied together with sinew-thread and an edging of antler on all three sides; the handle is a separate piece of wood nailed on; just above the hand-loop, which is of antler, is a cross-piece, also of antler. A large modern snow shovel from Ponds Inlet is 99 cm long, 33 cm wide (just below the hand-loop); it consists of three boards nailed together; edging at the bottom and a broad reinforcement of sheetiron; the hand-loop of wood, composed of three pieces; the thickness of the handle is increased by a piece of wood nailed on.[8]

Shovelling snow over the snow house is mostly the work of the women. The man is still making the platform in the house; if a ledge of snow has not been left standing, snow is shovelled together with the shovel and stamped firmly into a platform, whilst the floor is levelled; then a shelter wall is built at the door — or all according to the nature and intention of the house — a passage way, store room, etc. are built. Windows are put in (not in temporary houses) and a ventilating hole in the roof; sometimes a small chimney is used and this promotes the draught and prevents the roof from melting; I have not seen such a chimney but I was told of it at Iglulik. Then the house is finished as far as the man is concerned, and the women may come in and put things right, arrange the platforms as couches, put up the lamp and drying rack. Platform-skins, sleeping rugs and the other chattels are usually brought in through a hole in the wall, which is then closed up again, instead of bringing them through the low, partly "subterranean" doorway. As a rule, a newly built snow house is strong enough for a man to lie on top and close the crevices; but when it has been used for some time and the inner layer has been turned into ice, one may stand on top and stamp with the feet without doing any damage.

Many women, though not all can built snow houses, even if they have not usually the same skill as the men; they often help the men to cut the blocks. There are some men who never learn the art; a young married man at Iglulik could not build a snow house and the same was said of a man about fifty years old at the same place.

The size of the snow house and its arrangement depend upon what it is to be used for. Other demands are of course made of a snow house that is to be used as a dwelling for a couple of families

Fig. 77.Ground plan of snow house; Repulse Bay.

for a long period than of a house that is only intended to provide shelter for a man for one night. In the following I will describe different snow houses, showing their size and construction and how they are joined together into blocks of dwellings.

Fig. 77.Ground plan of snow house; Repulse Bay.

for a long period than of a house that is only intended to provide shelter for a man for one night. In the following I will describe different snow houses, showing their size and construction and how they are joined together into blocks of dwellings.

Fig. 77 shows the ground plan of a snow house at Repulse Bay, of the usual form. intended for two families. The diameter is 4.3 m, the height above the floor 2.65 m, platform height 0.55 m; above the doorway is a window of fresh-water ice, 2.05 m above the floor; its size is 60 × 55 cm; by the side platform there is a niche, about 20 cm deep. in which the women sitting sewing on the main platform can place their feet. In front of the house is a store room, the floor of which is about 20 cm lower than that of the house; from this an opening leads into the house and a wooden door on hinges out to the front room, which opens out with a semi-circular wall; the front room is where the dogs live in bad weather. At the side of the store is a sideroom for skin clothing.

The Eskimo terms for the various parts of the house are: ceiling: iluperuk; floor: nateq; main platform: igleq; side platform: akit; rear wall: kilo; door: uateruluk; store room: serdluaq; dog's room: uatlik; window: igalâq; airhole: qingaq.

This is the usual form and size of snow house intended as a dwelling for two families for long periods.[9] If there is only one family, they are mostly made smaller (3–3½ m in diameter); if there is a lack of blubber so that heating is difficult, they can be made very small; on Southampton Island I saw one in which not even the Eskimos could stand upright or lie outstretched on the platform.

Fig. 78 is a snow-house block inhabited by four families in March, 1922, at Itibdjeriang, on the east coast of Melville Peninsula. The smaller house is of the same type as that described in the foregoing, diameter 4.10 m. interior height 2.45 m, platform height 0.35 m; it is built of seven rows of blocks over the platform; the doorway forms a regular arch, 1,60 m high, 1.15 m wide; the left edge of the window is almost over the middle of the doorway; the window is a trapezoid slab of ice, 0.60 m high, 0.60 m wide at the bottom.

The large house is arranged differently, there being two main platforms and three (or four) lamp places; it is the usual type of house when intended for more than two families. The diameter is 5.60 m, height 3.15 m; the platform is 50 cm above the floor; the window 65 cm above the doorway, 55 × 70 cm; the doorway is arched. 1.80 m high, 1.40 m wide. The doorways of these two houses lead into a front room, 2.15 m high, from which lead a small opening into a room for skin clothing and also an entrance-door of wood on hinges, 85 × 45 cm, out to a bigger store room, 1.85 m high, built of five rows of blocks, in which dog harness, meat, etc. are kept; by the side of this is a smaller store room, 1.70 cm high, built of 6 rows of blocks; finally, a wooden door. 95 × 50 cm, leads into a front room, 2.00 m high, built of 6 rows of blocks, which provides a shelter for the dogs; and from this a door, 1.15 × 0.50 m, leads out into the open air.

Fig. 79 shows a bigger snow-house block, built in February, 1922, at Aua's River near Itibdjeriang and inhabited by the same group of Eskimos as the foregoing. The characteristic feature of this is the central system, with a number of small snow houses which all, directly or indirectly, merge into a centre room; the whole block has only one common exit, and one can pass from one house to the other without having to go outside. In its ground plan it resembles the house which Hall[10] figures from Nuvuk, although the latter is more simple.

The largest single snow house I have seen, at Pingerqalik in April 1923. was lined with skin and measured 5.5 m in diameter. 2.5 m high, both measures to the skin lining. The window consisted of two slabs of ice, 1.3 × 0.65 m; the door measured 0.75 × 0.50 m: there were two main platforms. There was a central store room, from which were doors to the house, to two smaller side rooms for clothing and meat and a wooden door to the dogs' room, in one side of which was a small opening into a separate little snow house which acted as a latrine. In February 1924 the same family lived at Pingerqalik in a snow house that had no skin lining. 6.5 m in diameter. 4 m high.

According to Capt. Comer. Boas[11] refers to a snow house on the west coast of Hudson Bay with a diameter of 7 m, height 4m. and Low[12] mentions one at Fullerton, 27 feet in diameter, 12 feet high: this, however, was too big for the material and had to be supported by battens.

Skin lining of snow houses is commonly used by the Iglulingmiut and Tunumeriut, but not by the Aivilingmiut; none of the earlier expedition reports mention skin-lined houses here either. I have seen skin-lined houses both at Repulse Bay and at Qajûvfik; but in both cases they belonged to Iglulingmiut who had moved down there.

The skin lining (iluperuk) is made of sealskin sewn together: more often it is worn-out tent skins that are used for this purpose. The hair side faces the interior of the house. The skin hangs ten to forty centimetres from the wall of the house and is held by a number of strings (sanariaq), both ends of which are fastened to wooden sticks; one of these rests on the outside of the snow house, the other holds the skins up; from the middle of the roof hangs a thick seal thong, thirty to forty em long, with a thick wooden stick at each end; the others are thinner and shorter. The skin lining usually extends right down to the platform and is fastened at the bottom with wooden pegs.

Thin slabs of fresh-water ice are oftenest used as windows in the snow house; these are hewn out with the ice pick, most easily at a place on the lake where two cracks cross; the shape of the ice-pane is usually trapezoid or rectangular: Parry mentions round windows. In skin-lined snow houses gut-skin windows are often used; at Ingnertoq I saw in March 1922 in a large, skin-lined house, a window formed of seven bearded-seal guts joined together and sewn fast to a skin frame about one metre wide, which was fastened to the skin lining. The gut-skin window gives more light and is easier to wipe clean of rime than the ice window; but it is not so tight.

Store room and doorway are usually built as separate houses, circular; more rarely they are of a more oval form as shown in Parry.[13] Only in one single instance, at Hall's Lake, have I seen a doorway with straight walls as seems to be the rule among the Copper Eskimos.[14]

On journeys which include women and children. snow bouses of the same plan as fig. 77 are usually built, but without a store room and window and with only a small shelter-wall in front of the door, which can be closed from the inside by means of a block of snow; if a lot of baggage is taken, a special house must sometimes be built for it. If men travel alone, small, very low snow houses are built without a platform. At the settlements small houses are often built for a dog with pups or as a latrine; for the latter purpose, however, a circular wall is often sufficient, merely to keep off the wind and the dogs.

Snow houses can generally be built in the course of October; in 1923 the first snow houses on Southampton Island were built in the middle of October. The change from a tent or qarmaq to a warm, tight snow house is a great comfort, even if at first, when the snow is soft and the temperature low, the snow house is quickly worn out. A month or six weeks may be taken as being the usual duration of a snow house in the cold winter period; skin-lined houses, however, can often last much longer, often the whole winter. When quite new the snow house is cold; but the heat of the lamp soon melts the innermost layer of snow and this is sucked up by the walls and freezes into ice, which makes the house tight and strong. Ventilation takes place through a small air hole, qingaq, "the nose of the house", which at night is closed with a piece of skin, a mitten, or some similar object (but not with snow, as that is too tight). But the time comes when the melted snow can no longer be sucked up and then the house begins to drip, a most uncomfortable time, when platform skins, rugs and clothing become wet. If there is much heat in the house, widening the air hole will often put a stop to the dripping; otherwise one tries to avoid it by cutting off the icicle or unevenness from which the drops are falling so that the water may run down the walls; or a lump of snow is put on to the place from which the drops fall; the lump then freezes on and will collect the melted water; it must be frequently renewed, however; if the dripping cannot be prevented, vessels must be placed under it. When a snow house has become so old that most of the wall has been turned to ice, it must be left; in the first place it is too cold, and secondly it drips incessantly. On Southampton Island we built a large snow house on November 25th; on December 8th it commenced to drip, but on December 25th it froze again owing to severe frost and then became lined with a layer of rime; on January 1st it was deserted. At Kingâdjuaq in April 1923 we came across a skin-lined house which had been inhabited all the winter; it was then completely "subterranean”, buried in snow; the window opened into a "well", supported by blocks of snow; the lower part of the skin lining was completely hidden by large masses of ice. formed by the melted water which had oozed down the walls.

In May the snow house becomes a less pleasant dwelling; the snow becomes very soft; holes are continually forming in the roof. which readily falls in and makes everything wet. Very often large bulges form in the roof, and they sink further and further down. until they break; for a time these bulges can be dealt with by tapping them of water by fixing a pointed cone of snow at the lowest part: from this the water runs in a stream. Otherwise the roof must be supported by means of rods and planks and it is at this time that the Eskimo moves into a qarmaq or, more often, a tent. When we left Iglulik on May 15th 1922, all the Eskimos were still living in snow houses; on the 18th at Amitsoq we met Eskimos of whom some lived in tents, others in snow houses. In the spring of 1923. on the way to Ponds Inlet, a snow house was built for the last time on 12th May, at Inuksuligârssuk, near the head of Milne Inlet.

From a hygienic point of view the snow house is undoubtedly an excellent dwelling. Its short lifetime involves that large heaps of refuse and dirt do not get time to accumulate. In snow houses which are used for a long time the women sometimes clean them out when they have become too dirty: With the ulo and the snow shovel they scrape a layer from the floor and a new snow layer is put down in its place. In many cases urine may not be passed inside the house, and even then only in a hole made for the purpose; bones and other refuse are collected behind the lamp or in a corner on the floor and are thrown to the dogs at certain intervals.

The temperature inside the snow house is illustrated by the following examples: the snow-house block fig. 78 at Itibdjeriang, 14th February 1922, 10 am; all lamps (1) burning; outside −34° C. On the platform in the living room: −3.1°; on the floor in the living room −6.0°; at man's height above the drying rack: +1.6°; on the platform in the small house −1.7°; on the floor, same house −8.0°; man's height above the drying rack: +2.0°; the floor in the front room: −10.2°; man's height same place: −1.8°, the floor in the store room: −24.2°.

Large skin-lined house at Pingerqalik, 14th April 1923, 3 pm.:

Air temperature: −10°; on the platform +4.2 C., floor 0°, at man's height above the platform: +6.4°. Four lamps burning.

Small skin-lined house at Qajuvfik, 23rd March 1923, 3pm. Two lamps burning, a number of people present; air temperature −30°: platform +5.2°, at man's height above it +9.8°, the floor +0.5°.

House at Pitorqaq, 27th January 1924; not skin-lined; outside −41°. On the floor −7°, middle of house −1°, 20 cm below middle of roof +4°.

For a snowhouse with all lamps burning and many people and dogs inside it, with an air temperature of −32°, Parry[15] recorded: over the drying rack +3°, two or three feet from it 0°, near the wall −5°.

A special use of the snow house is as a Festival or Dance House (qâgi). These are not built now; but formerly, when a number of people often gathered at one place, they were used and old people still alive can remember them and their furnishings. At Repulse Bay, festival houses were built in the form of two large, connected snow houses; in each of them was a platform, one for the men and one for the women; it was under the arch which joined the two houses that the dance proceeded. Hall[16] mentions a great feast at Nuvuk which took place in a house of this kind; from Repulse Bay he figures a dance house which differs in consisting of three connected snow houses. At Iglulik in winter, mask-dances were held in a large snow house, round, with no platform, the lamp on a block of snow in the middle; the men stood at one side, the women at the other, and the children between them. At Ponds Inlet, dance houses were most often built at Qilalukan, and they had the same form as the Iglulik house, i. e. without platform. These dance houses closely resemble that described by Boas[17] from Cumberland Gulf but differ in the positions of the men and women.

In May, when the snow house begins to become less comfortable as a dwelling, most Eskimos move into tents (Esk.: tupeq), a change that is just as pleasant as the move from tent to snow house in the cold, windy days of autumn. European canvas tents are now used. more and more, as they are lighter, quicker to pitch and not so warm in summer; on the other hand they are too cold in the late autumn. The oldfashioned skin tent is still the most commonly used, however.

The tent sheet may either be of seal skin or caribou skin; seal skin tents are the most common. As a type of the seal skin tent I will describe one (Fig. 80) which I saw in May, 1922, at Ipiutaq, near

Amitsoq, belonging to an Iglulik family who were returning home from a trading journey to Repulse Bay. The skeleton is of wooden poles and consists of: two poles (paqtaujaq) forming a cross at the fore part of the tent, 1.6 m high, the distance between them at the base being 2.8 m; a centre pole (sugaq), vertical, 1.8 m high, almost in the middle of the tent, set upon a flat stone; across the top of this is a ridge-pole (sánerutaq), flat, 80 cm long, having in the middle of the under side a socket for the centre pole; at right angles to this ridge-pole lie two sticks (tukimugutit), 45 cm long, with a distance of 40 cm between them; they are not fastened but are held in position by the pressure of the tent-sheet. From the top end of the centre pole a massive seal-thong (noqarut), stretched tight, runs to the cross at the front of the tent and from there to a large stone lying in front of the tent; the distance from the cross to the vertical pole is 1.5 m. This line is supported outside the tent by a vertical rod, 4.6 cm from the tent door and 2.6 cm from the stone; the latter holds the line tight and the whole tent upright. The tent-sheet (tupeq) is laid over this skeleton; it consists of ten seal skins sewn together; of these, the five which form the rear part of the tent (qingmerun) and the roof in the fort part (uming) are hairy, whilst the five in front are unhaired (nerdlernang) and translucent. The tent-sheet is held down and taut by 27 stones (perut) placed in a circle; when the tent is moved, these stones remain as the well-known tent rings. The doorway, the opening between the two flaps of the tent, may be fastened back or closed at will. The rear part of the tent is occupied by the platform, bounded at the front by a number of flat stones; it extends to the centre pole; here the width of the floor is 2.7 m, the depth of the platform is 2.0 m, depth of floor from platform to doorway 1.3 m.

I have seen this type of seal skin tent, with various small modifications, in use from Southampton Island to Ponds Inlet. On Southampton Island I have seen in several tents three sticks laid at right angles to the ridge-pole on the centre-pole, which is sometimes inserted through loops on the tent sheet; other rods are sometimes placed under the tent sheet from the crossed-poles obliquely back to the ground in order to stretch the tent further out. One small tent had the vertical centre pole replaced by two oblique poles, joined at the top by a ridge-pole.

At Ponds Inlet I saw several tents in which the centre pole was replaced by two oblique poles forming a cross; sometimes there was also a third pole which ran from the cross along the rear wall of the tent, and in one case there I saw two longitudinal poles connecting the two crosses, thus making the seal thong along the ridge of the tent superfluous. The construction used seemed to depend upon how many poles they had. The construction last referred to required seven long poles as compared with the three poles of the first-mentioned; but of course this made a much firmer skeleton. The tent described by Boas[18] from Ponds Inlet only differs from the one first described above in that. instead of two crossed poles in the front. it had one vertical and one oblique pole. Parry[19] described a tent at Iglulik which had only one pole, a vertical centre pole with a ridgepole besides a pole outside the tent, and this pole consisted of several pieces of antler and bone lashed together; in this case a part of the tent-sheet was made of walrus hide, cut thin and translucent. Parry[20] also refers to double tents, two tents of this kind joined at the doorway, with one common door at the side.

A tent sheet from Ponds Inlet, belonging to a tent with two crosses, is 3.70 m long, 4.50 m wide; it consists of four whole, hairy and four whole, hairless seal skins, as well as a large number of small pieces, twelve to thirteen skins seeming to have been used to make this tent sheet. The rear part is hairy, the fore part unhaired except two strips on each side of the ridge of the tent.

Another tent-sheet, from the Aivilingmiut, is 4.05 × 3.20 m wholly of hairy skin, 4 whole and 17 pieces, presumably about 7 skins in

all. To it belong a ridge-pole, a board 76 × 10 cm, in the ends of which are rectangular, oblique holes for the stays which have supported it. A piece of seal skin, 30 cm wide, hangs down from its lower edge.

Wooden doors are now commonly used for seal-skin tents; as a rule they are the same doors that are used for the snow houses in winters; in these cases the tent sheet is sewn to the frame of the door.

I saw at Ponds Inlet that holes in the tent sheet were repaired by means of small, round, white pieces of seal skin, over which were sewn smaller, round pieces of dark seal skin; splits were repaired with strips of white seal skin, over which were sewn two rows of small, square, black pieces of seal skin.

Of caribou skin tents I have only seen a single specimen, at Ipiutaq May 1922 (Fig. 81). Its skeleton consisted of two crosses of poles 1.8 m high, at a distance of 1.2 m from each other. The crosses were connected by a seal thong which passed from a stone 3.5 m in front of the tent. The tent sheet was of hairy caribou skin with the hair on the outside; only the door consisted of unhaired skin scraped thin; there were 24 stones. This caribou skin tent is warmer, but not so durable as seal-skin tents and is not used to any great extent.

Parry[21] refers to a tent at Lyon Inlet thus: "It consisted of a rude circular wall of loose stones, from six to eight feet in diameter and three in height, in the centre of which stood an upright pole made of several pieces of firwood lashed together by thongs and serving as a support to the deer-skins that formed the top covering." Tent rings of the kind here described, consisting of closely placed, big stones or walls of smaller stones, are. as mentioned in my archaeolegical work,[22] extremely common in Repulse Bay and on the southern half of Melville Peninsula; such walls are never used now; like the corresponding, heavy oval tent rings, they seem to be connected with the Thule culture; but from Parry's description we see that they have been in use right up to his time. The modern tent rings form a circular or slightly oval ring of stones at intervals; inside are the platform stones and, very often, three stones placed together where the fire-place has been. In the Iglulik area, where large stones are not plentiful, lime grits were often used to weight the tent sheet. and thus the tent ring here often appears merely as a low mound of grits.

On Button Point I saw quite a small tent. used by a mentally deficient girl; it was built of three small poles which met at the middle, over which the tent sheet was drawn; the height was only a good metre and the owner could just sit upright in it.

When cooking in the open air a small kitchen tent (talo) is often built — a skin laid over two poles to provide shelter from the wind; here the cooking is done by means of blubber and bones or with heather, bilberry or willow twigs; bear bones are said to be particularly good to cook with.

When a tent is to be pitched the procedure is as follows: Large stones are laid in a ring; the tent skin is spread out and drawn into position; stones are laid on the rear part of the tent, the two fore cross-poles are put in and the line from them to the big stone is connected, after which the cross is raised; the centre-pole is erected and finally the tent sheet is stretched on all sides and the stones laid on. In windy weather especially it is necessary that these are near at hand (Southampton Island, October 1922).

In the unpleasant transitional periods autumn and spring many Eskimos use a number of forms of dwellings which with a collective Eskimo title are called qarmat, or autumn houses, as it is principally in the autumn that they are used. They consist of a wall (qarmaq) which may be of earth, stone, whale skulls, ice or snow, and a roof (ulinga) consisting of the tent-sheet and supported by the tent poles.

The qarmat of stones, earth and whale skulls are often built upon the sites of old winter houses of the Thule culture period, as here the material is right at hand. The qarmaq is distinct from the old winter house in that it is a purely temporary dwelling, built much less solidly, and in having a skin roof, whereas the winter house has had a roof of earth and stones. supported by whale bones. I have seen qarmat built on the sites of old winter houses at Kûk, Southampton Island (five, only about two years old), Naujan (one, also quite recent) and at several places at Ponds Inlet (Qilalukan, Mitimatalik, Qaersut, Iterdleq). At Igiulik it can be seen that five of the ruins are relatively recent and built into earlier house ruins, the walls of which have been partly preserved on the outside in the form of low earthern mounds; it was presumably these bone houses which Parry[23] found inhabited in the autumn and the first part of the winter with roofs, first of skin, later of snow. I have seen similar old qarmat built into old house ruins at Pingerqalik and Tikerâq. Presumably it is these which Parry[24] mentions on Calthorpe Island. The Eskimos themselves differentiate between the old house ruins, which they call iglorssuit, "big houses", and the autumn houses, qarmat.

As the type of these more solidly built qarmat, built of stone, earth and whale bones, I will take the one which the Aivilik Patdloq built in the autumn of 1920 on the site of an old house ruin at Naujan in Repulse Bay (Fig. 82). It is built into a slope. The walls reach 80 cm above the platform and are built of stones, turf and seven whale skulls; moss is filled in between the stones. The platforms are covered with flat stones; the door is 1 m wide and a half metre high; it is covered over with a flat stone. Over the door a whale rib has formed the upper frame for a gut-skin window; the tent sheet served as a roof. The whole plan and construction is very near to the qarmat described by Boas[25] from Cumberland Culf.

Five new qarmat at Kûk, Southampton Island, were quite similar; one of the houses, however, had two platforms like the snow house fig. 78. For six days at the end of October 1922 we lived in one of these qarmat; the wall was heightened with two courses of snow blocks and above these the tent skin was laid as a roof. The many qarmat built upon house ruins at Ponds Inlet also have the same construction; but by no means all of them have whale skulls in the walls.

At one time these solid qarmat seem to have been more generally used than now. Aua (about 60 years old) told me that when his father was a small boy, Eskimos lived in qarmat at Iglulik, Pingerqalik, Tikerâq, Ugle and Uglerlârssuk. And it was presumably qarmat that Sherard Osborn[26] saw at Ponds Inlet and describes as winter houses: ". . . sunk from three to four feet below the level of the ground: a ring of stones — few feet high, were all the vestiges we saw. No doubt they completed the habitation by building a house of snow of the usual dome shape over the stones and sunken floor . . ." Presumably it was the settlement Iterdleq at Button Point that Osborn has seen. When Knud Rasmussen[27] says that the immigrants from Ponds Inlet to Cape York on their way "built houses of stone and turf in the autumn", the qarmat is also undoubtedly meant.

Permanent qarmat are, however, also built at places where there are no house ruins; in these cases they are always without whale skulls. At Nutarasungneq and Kuktujoq, between Janes' Creek and Albert Harbour at Ponds Inlet, there are seven and six qarmat respectively, built entirely of stones; they seem to be fairly recent. A single, rather older one, is at Mitimatalik. Padloq told me that a few years ago he built a qarmat at Naulingniarbik river at Usugarsuk, and one of the recently erected qarmat at Kûk lay some distance from the others, was rather small and built entirely of turf.

Still less solid buildings than these, but resembling them, are the hunting shelters (siniktorvik) which the caribou hunters often build when sleeping out at night and no tent has been taken along. A number of stones are placed in a ring or a square; at one end an elevation is made on which to rest the head, and two caribou skins are used to form the roof. These hunting shelters, which often are only used for one night, are frequently met with, especially in the interior.

The ice house is another form of qarmaq. During our sojourn at Hansine Lake on Southampton Island we lived in an ice house from 11th to 22nd October 1922. Its erection proceeded in the following manner: The work was commenced three days before, the ice being hewn away from an area of the lake near the shore on which the ice house was to be built; the reason was that the ice covering the lake had become too thick to build with, and therefore new, thinner ice had to be formed; the thick, useless slabs were pushed in under the ice. In the course of three days the new ice had attained a thickness of 12–15 cm; it was then cut into eight square slabs 1.8 × 1.0 m by means of the ice pick and these slabs were taken up one by one, a hole being made in the middle and through this the loop of a seal thong was run; this loop was then caught by a salmon spear pushed in under the ice and drawn up to the top, where the two ends of the thong were run through the loop and two or three men dragged the slab, by means of these two ends, up on to the firm ice, raised it on edge and pulled it ashore. On a stony, slightly sloping surface by the shore the slabs were placed on edge, leaning slightly inwards, and were cemented together with wet snow. Two slabs were broken during transportation and were cemented together again with wet snow. They were trimmed at the top to make them all the same height; owing to the dip of the terrain the height of the slabs at the front wall was 1.70 m, at the rear wall 1.50 m. In the walls a door was cut facing SE; just big enough for a man to creep through. Before the walls were closed up a number of stones were dragged in, particularly flat stones suitable as edge-stones for the platform, and after that a quantity of grit and small stones was scraped from the floor and built into a platform 30 cm above the floor; two small side platforms were also made. The diameter of the house was 4 metres; of this the platform occupied 2.2 m. The tent-sheet was used for a roof, being spread out flat so that the hairy part covered the rear side of the house, the front side being covered with a double fold of the hairless part. The tent sheet was supported by the tent poles and two salmon spears laid from wall to wall and fastened by a strong seal thong which was tied round the house about half a metre below the upper edge of the slabs, where a number of notches had Image missingFig. 83.Ice house; Southampton Island. been hewn in the angles of the walls. At night an ice block was used as a door, cemented in with dry snow, and outside the door a small shelter wall was built of snow. This house was much warmer than the tent and pleasantly light; but it did not become as tight and warm as a snow house. Fig. 83 shows this ice house with the two other forms of dwellings, the tent and the snow house, at Hansine Lake, October 21st.

Parry[28] mentions and figures an ice house with a skin roof. from Iglulik. This differs from the foregoing in that the walls are mostly built of two slabs placed one on top of the other, and in having a long entrance passage, likewise of ice slabs. In the same place he shows a dog's house and kayak supports of fresh-water ice. Gilder[29] too, says that the Aivilik Eskimo "Toolooah" built an ice house on King Williams Land.

At Hall's Lake, near Iglulik, I saw on March 23rd, 1922, a deserted ice house. It was built of 14 ice slabs, about 10 cm thick, rather narrow, 1.5 × 0.7 m, inclining slightly inwards. Its diameter was 3½ m. On this the roof was formed of four rows of snow blocks, 60 × 30 cm; the platforms were 40 cm above the floor and built of flat limestones; in front of the door there were two small fore-rooms of snow. This house is thus a transitional form between the qarmaq proper with skin roof and the snow house. Lyon,[30] too, refers to ice houses with snow roofs, from Iglulik.

The snow-qarmaq. Is the most frequently used and the only one that is sometimes built in spring too. It is simply the snow house. uncompleted, the domed snow roof being replaced by the flat, outspread tent-sheet. How high the wall is built depends upon the nature of the snow; the softer it is, the less the wall can stand inclining inwards. These qarmat are used both in the autumn, before the snow has become sufficiently firm, and in spring, when the heat of the sun makes the snow house unsafe. I have seen these qarmal used right up to June 10th; as a rule, however, a move is made into the tent in the middle of May.

Finally it remains to mention that during the past few years experiments have been made to get the Eskimos at Ponds Inlet to live. in wooden houses (Fig. 84), rectangular houses of wood with a saddle-shaped roof, the interior containing a main platform and two-side platforms. Originally these wooden houses were doubtless built by the competing trading companies in order to retain a hold on the Eskimos. With few exceptions the experiment does not seem to have been a success. With their lack of cleanliness, which does not matter so much in a snow house as they soon have to move into a new one, such piles of dirt accumulate in these wooden houses that the stench becomes almost intolerable, especially when in winter they are almost hermetically sealed up.

This reminds me of an episode at Ponds Inlet: At the settlement lived an old man from Iglulik, Utsutsiaq and his old wife, and they had obtained a wooden house too. With their instinctive impulse to pick everything up and keep it, large quantities of all kinds of rubbish had in the course of the years accumulated in their house, and it all produced an almost unbearable smell. The zealous manager of the trading station thought that this was going too far and ordered the house to be removed. The whole population of the settlement was drummed up and they carried the house to a new site. When it was removed, there lay on its old site an enormous heap of old bones, shreds of skin and clothing, pieces of wood, old, worn-out pans and meat-cans, turf, heather, and everything was sodden with blubber. This was in the evening, but the manager said that next morning the whole lot was to be thrown into the sea. When he awoke next morning, rather early, he found that the whole heap had disappeared. And as this Eskimo industry so early in the day seemed suspicious to him, he looked into things: the old people had spent the whole night carrying their accumulated chattels to their new house which was now filled with them, and they themselves lay fast. asleep in the consciousness of having performed a great and useful work.

The main platform in house and tent serves at night as a bed, by day as a work-place for the women who sit there and sew, tend the lamps, cook and eat; when the men are in the house they usually sit on the platform too.

The platform is covered with skins; but under these is as a rule a platform covering, partly for the purpose of making the platform comfortable and especially to keep the platform skins from direct contact with the snow in the snow house and thus prevent them. from becoming wet on the under side. In the tent and qarmaq where this precaution is not necessary, it is as a rule sufficient to remove all unevenness from the platform. Sometimes, however, a layer of heather (Cassiope tetragona) is spread in order to give increased comfort, and along the fore edge of the platform a row of slightly bigger stones is laid as a kind of head guard. On this the skins are laid, most frequently caribou skins. the first layer usually with the hair towards the ground, the others with the hair upwards; sometimes seal skin is used for the lowest layer.

In the snow house a pole is often laid along the front edge of the platform to prevent it from being broken by use. The platform covering is mostly a thick layer of heather, Cassiope, which is more or less easily procurable in most places; other dwarf bushes may be used among the heather. In the Iglulik area, where these are often very scarce, small pieces of limestone are frequently used instead. Of more durable kind are the mats (atdliaq) which are occasionally plaited of willow twigs or Cassiope: Thin twigs are laid in bunches and these are tied together into mats; on moving these mats can be taken along and can be used on journeys, when otherwise seal skins or caribou skins, with the hair downwards, are used. A mat of this kind, from the Iglulingmiut at Repulse Bay, consists of 43 thin bunches of Cassiope, held together by four longitudinal cords of plaited sinew thread: the dimensions are 1.05 × 0.85 m. Another specimen is 1.25 × 0.65 m and consists of still thinner bunches of Cassiope, held together by five longitudinal cords of sinew thread; on this a number of the bunches are wound with sinew thread. A third mat, found in a tent ring at Chesterfield Inlet, measures 0.65 × 0.40 m and consists of thin willow twigs, held together by two thin longitudinal cords of seal theng, to which the various bunches are tied with sinew thread.

In earlier times platform coverings of plaited baleen have been used; an Eskimo at Ponds Inlet recognised the baleen mats I had found at the excavations at Qilalukan[31] as such nuluavinik, plaitings for platform coverings. From Iglulik Parry[32] says: "The beds are arranged by first covering the snow with a quantity of small stones, over which is laid their paddles, tent poles, and some blades. of whalebone: above these they place a number of little pieces of net-work, made of thin slips of whalebone, and lastly a quantity of twigs of birch and of the Andromeda tetragona." Fig. 85 shows a baleen mat from Parry's Expedition 1822, collected on Winter Island. and now in the British Museum; on the label it is stated to be "Net used by the Eskimaux for laying under their beds also supposed to be used for fishing". It is of exactly the same type as the mats Image missingFig. 85.Platform covering of baleen; Parry's Collection, British Museum. Image missingFig. 86.Sleeping rug. excavated at Qilalukan and provides further confirmation of the supposed use of these.

How many layers of caribou skin are laid upon the platform depends upon how many they have; the usual number is three, of which the one underneath, which is most exposed to damp, is poor skin with the hair downwards. The top layer, which serves as a bed for the naked body, consists of the best skins.

To cover them at night they use rugs of caribou skin (qeipik). Fig. 86 (Iglulik) is one of these sleeping rugs. It is sewn together of three long pieces which narrow towards the foot end; on this specimen the middle portion is increased in width by a fourth piece, and between the two side pieces several smaller pieces have been inserted and form the bottom of the rug. When folded, the rug is shaped like a sleeping bag, cut open in one side nearly to the bottom; the hair-side is turned inwards. The top edge is closely trimmed with hairy caribou skin fringe, about 15 cm long, and it is further strengthened by a very narrow strip of short-haired caribou skin sewn on. The length of the rug is 1,40 m, width at the top unfolded. 1.35 m. In a folded state, when the edges at the top lie together, the width there is about 70 cm, at the seam about 40 cm from the bottom it is about 60 cm wide; from there the bottom is evenly rounded.

The size of the rug is adjusted to the size of the family, for the whole family lies under it. The fringe, which is always used because it keeps the neck warm, is also mentioned by Parry;[33] once I have seen the front edge of the rug decorated with a strip of yellow seal skin, over which a thinner strip of black seal skin was sewn.

When hunting and travelling the men sometimes use sleeping bags, also of caribou skin with the hair inwards; but this is something that is comparatively new; formerly they either slept in an extra rug or simply in their fur frock.

A pillow (akiseruluk), which I saw at Pingerqalik, was a long sausage, about 60 × 22 × 12 cm, made of caribou skin with the hair turned inwards and tightly stuffed with caribou hair; as a rule the rolled-up clothing serves as a pillow.

In a house where two families live, the wives lie on the outer side of the platform, then come small children, then the men and in the middle lie the bigger children or guests. When water or urine is spilled on the platform skins or clothing, it is removed with the water scraper (kiliutaq). Fig. 67.7 shows the typical form of this implement. It is of caribou scapula, with the joint-head cut off and smoothed and the blade cut round at the bottom; 15½ cm long. Seven other specimens, with lengths varying from 13½ to 18 cm, are formed in exactly the same manner. Fig. 67. 8 is another form of water scraper from Ponds Inlet, made of a narwhal scapula; the hole in the handle is closed with a wooden plug; it is 14½ cm long.

On the side platforms are the lamps, drying rack, cooking pots and other cooking utensils. The usual form of lamp (quidleq) will be seen on fig. 87 (Aivilingmiut, Southampton Island). It is a large. half-moon. shaped bowl of soapstone, 78 cm long, 36 cm wide and about 4 cm deep; thickness 3–4 cm; the front edge is slightly curved, the rear edge very much so. A number of smaller lamps are of similar shape:

| Aivilingmiut, | length | 46 | cm, | breadth | 22 | cm, | depth | 2.5 | cm |

| Aivilingmiut— | length— | 35 | cm,„ | breadth— | 16 | cm,„ | depth— | 2 | cm„ |

| Aivilingmiut— | length— | 34½ | cm,„ | breadth— | 14 | cm,„ | depth— | 3 | cm„ |

| Aivilingmiut— | length— | 34 | cm,„ | breadth— | 19 | cm,„ | depth— | 4 | cm„ |

| Aivilingmiut— | length— | 22½ | cm,„ | breadth— | 13 | cm,„ | depth— | 3 | cm„ |

| Repulse Bay, | length— | 69 | cm,„ | breadth— | 29 | cm,„ | depth— | 5 | cm„ |

| Repulse Bay— | length— | 38 | cm,„ | breadth— | 19 | cm,„ | depth— | 2 | cm„ |

| Itibdjeriang, | length— | 36 | cm,„ | breadth— | 13 | cm,„ | depth— | 4 | cm„ |

| Ingnertoq | length— | 36 | cm,„ | breadth— | 15 | cm,„ | depth— | 3.3 | cm„ |

| Kingâdjuaq | length— | 21 | cm,„ | breadth— | 10 | cm,„ | depth— | 1.5 | cm„ |

| Iglulik | length— | 17 | cm,„ | breadth— | 8½ | cm,„ | depth— | 1.5 | cm„ |

| Iglulik— | length— | 26 | cm,„ | breadth— | 12 | cm,„ | depth— | 2.7 | cm„ |

| Ponds Inlet | length— | 44 | cm,„ | breadth— | 19 | cm,„ | depth— | 3 | cm„ |

It will be seen that the proportions between length and breadth of most of the lamps are fairly constant, a little over 2; only in a Image missingFig. 88.Lamp with partition. few does it fall below 2, but never going below 1,7; on one it rises to 2,8.

Only two of the lamps differ in form from the others; they were both made by the same man and are quite new: Fig. 88 (Ingnertoq) has partitions which at the rear wall form three sections to hold blubber fibre and other incombustible matter. The other, from Kingâdjuaq, is a very small lamp having at the ends projecting blocks, 4 cm wide, 6 cm high, on which the cooking pot can stand. At Ponds Inlet, too, I saw a lamp with a longitudinal partition.

Most lamps are fairly flat; on some the front edge passes smoothly into the bottom, on others it appears as a distinct rim. Two lamps are very crude, up to 5 cm thick and have rounded corners; but most of them resemble Fig. 87 in being rather thin with angular corners. The front edge is oftenest slightly curved. although in a few cases nearly straight.

The type of lamp figured by Parry[34] is quite the same as that prevailing to-day. Boas[35] says that the lamps at Cumberland Gulf and Ponds Inlet are deeper than the lamps from the west coast of Hudson Bay; but this is not the rule, at any rate at Ponds Inlet; it is the same type of lamp that is used by the Aiviliks and the Ponds Inlet Eskimos.

Lyon[36] found a lamp that was made of granite slabs cemented together; it is now in the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, and is 32½ cm long, 15 cm wide; the bottom is made of two longitudinal pieces placed at angles to each other; the front edge is almost straight, the back edge curved, made of several pieces cemented together.

Nowadays lamps of sheet iron are often used, mostly of the same shape as the stone lamps; in case of need a naturally hollowed stone, a saucer or a cooking-pot lid may be used.

The lamp is placed on three sticks (pituangit), which are pushed down into the snow of the platform, or, in the tent or qarmaq, on three stones. A bowl for collecting dripping blubber, such as often used by other Eskimos, I have never seen used by the Iglulik Eskimos; Parry,[37] however, mentions "a small skin basket for catching the oil that falls over".

When the lamp is to be lighted, it is filled with blubber; this may be in liquid or solid form. In spring, when ũtoq seal-hunting is going on, a large store of blubber is usually collected; this is cut up and filled into a whole-flayed sealskin, the openings of which are then closed and it is placed in a meat cache. There it lies until the summer is over. The pieces of blubber are gradually turned into liquid fat — train oil — by fermentation. When in winter these blubber bags (oqsut) are taken out, the blubber is ready for use and may be poured directly into the lamp.[38] If on the other hand the blubber is of recently killed animals it must be beaten in order to press the oil out. It is placed on a flat stone (kauarsivik) and beaten. with the blubber pounder (kauarsit). The common form of this implement will be seen on fig. 89 (Ponds Inlet). It is a branch of antler with the appendent piece of the stem; the length of the handle is 27 cm, that of the head 12 cm. Another of the seven blubber. pounders in the collection has a head only 7 cm long. A European hammer, or the back of an axe, is often used for blubber pounding. however.

When the blubber has been pounded. it is laid in the lamp where it gradually melts. Moss (ikúmaq) is usually used for the wick of the lamp, after having been chopped small with the ulo. (Parry[39] says that it is rubbed with the hands): I have also seen cotton grass used as a wick (on Southampton Island); sometimes the moss is mixed with willow fluff. The finely-chopped moss is moistened with oil and placed in a row of lumps along the front edge of the lamp, in which oil, if they have it, is poured so that it just reaches them. They are then lighted and teased out with the lamp trimmer into a continuous

strip; there must be no points or other irregularities in the strip, as this makes the flame smoke, and smoke is detested by the Eskimos. The wick should preferably be renewed every day.

The typical form of lamp trimmer (tarqut) is shown on Fig. 90.1;[40] this one is from Itibdjeriang. It consists of a fine-grained marly slate which is only found in Admiralty Inlet and has a four-sided, richly decorated handle and a round point, bent over at the end, 18 cm long. A lamp trimmer from Repulse Bay of the same material and shape is 19 cm long and its handle is decorated with regular transversal stripes. A small lamp trimmer from Iglulik, of the same material, is only 10 cm long, with no distinct handle but with a bent point. Fig. 90.2 (Iglulingmiut, Ponds Inlet) is of the same shape but has a handle of ivory and a point of iron; 16 cm long. Fig. 90.3 (Itibdjeriang) reproduces the same form in wood; 23½ cm long. Besides this traditional form of lamp trimmer, more simple forms are also met with, a plain stick of wood, and formerly often a seal penis bone. It is not unusual to find the peculiar limestone concretions from Committee Bay used as lamp trimmers; these are also mentioned by Boas[41] as "small petrifacts (largely as fish)". Parry[42] refers to lamp trimmers of asbestos.

In the snow house it is an easy matter for snow to get into the lamp. with the result that it burns badly. This water is taken out by means of holding a lump of snow in the oil; the snow then absorbs. the water but not the oil. On journeys a small box, filled with chopped, oily lamp moss is often taken on journeys to facilitate the work.

An implement that is sometimes used in connection with the lamp is the blubber dripper (Itipserfik); fig. 91 (Iglulik) is of antler, 32 cm long, flat, slightly curved, with the concave edge cut into notches; at the ends are holes for the cords, and from these holes grooves lead upwards. Another, from Itibdjeriang is a straight wooden stick, 41 cm long. This implement is hung horizontally over the lamp by cords at both ends. the cords being fastened to the drying rack. The lump of blubber is laid above the stick and it melts with the heat of the lamp and drips down into it. Sometimes a skin thong is used instead of a stick. I have only seen the blubber dripper used by a few Iglulingmiut families; but I have found a piece of one in a recent qarmaq at Ponds Inlet; the Aiviliks are also said to have used it formerly.

The size of the flame of the lamp depends upon the circumstances; if food is to be cooked and there is plenty of blubber, the whole wick burns and the lamp can then give off considerable heat. Cooking by means of the blubber lamp always proceeds slowly, however. A small, round, iron pan with three large pieces of seal Image missingFig. 92.Drying frames. meat, a meal for two adults and a child, will with a 20 cm flame be cooked in an hour and a quarter. A large oval iron cooking pot, with caribou meat for four men and a child, cooked over a 40 cm flame, is ready in two hours. The temperature for the meat and in the house naturally plays a great part. If no cooking is being done, only a small part of the wick burns; at night a very little flame burns — if this is not extinguished too.

Over the lamp is the drying rack (pauktutit). It consists of three rods, one vertical, standing in the corner of the side platform, and two horizontal, which are stuck into the snow wall at right angles to each other; the ends of these three sticks are lashed together. A fourth stick is then put into the wall at right angles to the direction of the lamp but nearer to the wall; its other end rests upon the stick that is parallel with the lamp. On the two sticks at right angles to the lamp hangs the cooking pot suspended by cords, and over them, resting on the sticks, is the drying frame (ingnitaq). It consists of a frame of wood or bone and a net of cord or strips of skin. The usual form is shown in fig. 92.1 (Ponds Inlet); it is a halfmoon shaped wooden frame, 81 cm long, 47 cm wide, and a net of thin strips of seal skin fastened to holes in the frame. Fig. 92.2 (Iglulik) is a more primitive form, 55 × 40 cm; the frame is made of two curved pieces of antler; the net is of sinew-thread cord, strung rather irregularly. A similar, irregular, oval form is seen on the drying frame figured by Parry.[43] At one place, Ingnertoq, I saw a circular frame. In plaiting the net for the drying frame an Eskimo on Southampton Island started at the frame, the meshes gradually becoming wider: in the centre they were gathered into a star. All clothing that is to be dried is laid upon the drying frame, and it is particularly for this purpose that the lamp also burns during the night. In two skin-lined houses at Iglulik and Pingerqalik I have seen bigger drying racks, two parallel rods being placed under the roof, at right angles to the platform; a seal thong was stretched between them and on this were hung dog-traces, etc., for which there was not room on the drying rack over the lamp.

The cooking pot (uvkusik) of former times was of soapstone, oblong, with sharp corners and suspension cords and a kind of lug, a projecting ledge at the ends, as shown on Parry's figures[44] and as also occur in the Anangiarssuk find.[45] Nowadays soapstone cooking pots are very rare; the only one I saw, fig. 93, 1 bought of an Aivilik at Repulse Bay, and he bought it some years before of a Netsilik. It is oblong, 42 cm long, greatest breadth 15 and depth 11 cm; at one end the breadth at the top is 14½ and at the bottom 13½ cm, at the other end 13 and 11 cm; its thickness is 1.3 to 1,5 cm. The length seems to have been greater originally, one end-piece being a separate slab tied to the remainder of the pot, which is in one piece, by a band of iron. One side of the pot has been cracked, but is repaired with copper wire. In the corners there are suspension holes, opening into the upper edge and also into the sides or end-pieces.

Nowadays the cooking pots used are of European make. The heavy, awkward and fragile soapstone cooking pots were among the first to be displaced by European culture. If a European cooking pot cannot be afforded, they make one of sheet-iron of the same shape as the old soapstone pot. One of these, from Ponds Inlet, is almost rectangular. 39 × 18 × 14 cm; width at the ends at the top 16, at the bottom 13 cm. In the corners are suspension holes, in which are two pieces of wire.

When the meat is cooked it is lifted out of the pot with a meat fork (ungangiut), most often simply a pointed bone, sometimes more carefully made with a carved handle like that figured by Hall[46] and Boas.[47] Two meat forks from the Aivilingmiut on Southampton Island have two prongs, but this is presumably the result of European influence. One is of ivory, 27 cm long, 1,8 cm wide, curved, cut at the fore end into two points, 4 cm long; the other is 23 cm long, has a wooden handle and two bone points. 8 cm long. tied on with seal thong.

The meat is served up into meat trays (pûgutaq) of wood. The most common form is oval, made of a flat bottom and vertical sides. Fig. 94 a (Ponds Inlet) is an oval meat tray of wood; the bottom is Image missingFig. 93.Cooking pot of soapstone. made of two pieces, the sides are vertical and made of two pieces of wood bent together and joined with nails and wire. Length 44, breadth 27, depth 7 cm, of which the bottom measures 1½ cm. A number of other meat trays of the same type have lengths from 24 to 54 cm, breadths 13 to 34 and depths 4 to 10 cm. Similar trays are mentioned by Parry.[48] One from Itibdjeriang is, as an exception, circular, 21 cm in diameter, 7 cm deep.

Fig. 94 b (Ingnertoq) is a meat tray of another form, hollowed out of a single piece of wood; at the ends are projecting pieces for handles; in the middle of the under side is a flat surface for it to rest on; 46 cm long, 25 cm wide, 8½ cm deep, 1–2 cm thick.

Exactly similar wooden vessels are used as blubber trays for holding unused pieces of blubber.

Dippers (qajûtaq) for soup, water, oil and other liquids are usually of the form shown on fig. 95 (Aivilingmiut), It is of musk-ox horn, wide, deep, with a short, turned up handle; the length with the Image missingFig. 94.Meat trays. handle is 20 cm, width 20 cm, depth 6 cm; a crack in the front edge has been repaired with wire. A number of exactly similar dippers have the following dimensions: 21 × 17 × 5½ (Ponds Inlet, suspension hole in the handle); 21 × 21 × 6 (Repulse Bay); 11 × 9 × 4; 23 × 19 × 5½; 17 × 17 × 5 (Beach Point). A specimen from Admiralty Inlet (Ulukssan) differs in the breadth, the dipper itself being 9 cm long, 16 cm wide and 3½ cm deep, with a handle, only slightly curved, 5 cm long. These musk-ox dippers have also been the common form in earlier times, as Parry[49] and Boas[50] figure. Now, when Image missingFig. 95.Musk ox dipper. Image missingFig. 96.Meat knife. the musk ox is exterminated or at any rate very rare in their territory, the Iglulik Eskimos often buy these dippers from the Netsiliks.

Formerly they also used dippers of sealskin with a bone edging, or without this. A model of a water dipper from the Aivilingmiut, Qajûvfik, is of bearded-seal skin with a flat, oval bottom, 14 × 9 cm, and vertical sides; a stick of wood, 39 cm long, serves as a handle. A model from the Iglulingmiut, Qajûvfik, comes to a point at the bottom; diameter at the top 10 cm, 10 cm deep; a seal rib, 20 cm long, serves as a handle.

For eating thick blood soup, etc. they use small, flat spoons (alûn) of antler. One of these spoons from Ponds Inlet is 18 cm long, of which the bowl, 2½ cm wide, accounts for 5 cm. Boas[51] figures a small spoon of musk-ox horn. But nowadays most Eskimo families have European spoons and forks.

Parry[52] figures cups (imuseq), formed of the hollowed-out points of musk-ox horn, the point itself forming a handle, which is furnished with a row of notches, and he mentions. "circular and oval vessels of whalebone of various sizes" and "a number of smaller vessels of skin sewed neatly together". According to an old Eskimo woman, baleen cups were still in use at Iglulik fifty years ago.

Water pails (qátaq) of sealskin were used in former times. Boas[53] figures one of these, and Parry[54] mentions "a large basket of the same material (skin) resembling a common sieve in shape, but with the bottom close and tight". A newly made water pail from the Iglulingmiut, Qajûvfik, is of black, unhaired seal skin with the hair side inwards. It consists of an oval bottom, 23 × 26 cm, formed of two pieces and vertical sides of two pieces sewn together with a longitudinal seam; 22 cm high. The upper rim, 1 cm wide, is bent over and the edge sewn down on the outer side. A handle, 3½ cm wide, is split into two thongs at each end, and these are sewn on to the rim at a distance of 6 cm apart. At one time cylindrical vessels of seal skin were used as urine containers (qorbik); nowadays an empty meat can usually serves.

Knives (pilaut) are now usually the steel snow knife or European table and pocket knives. There still remain many flensing knives of a certain type, however, which they make themselves, a type which is represented by fig. 96 (Ingnertoq). It is a large, broad-bladed, two-edged knife, 45 cm long, of which the iron blade measures 26. The handle, which is of wood, with an iron reinforcement at the fore end, is so long that it can be gripped with both hands; sometimes these are also used as snow knives. Four other knives, all from Iglulik, are of the same form:

| Lengths respectively | 41 | 35 | 32 | 29 | cm |

| Of which the blade is | 20 | 18 | 13 | 10 | cm„ |

| Width of blade | 8 | 7 | 5½ | 5½ | cm„ |

They all widen out at the handle end and there are projections at the sides of the handles, mostly near its fore end, however. A two-edged meat knife from Iglulik has a flat handle of antler. 3.7 cm wide at the rear end, widening out at the other end to 4.2 cm; in a slot in this the symmetrical iron blade. 4.8 cm wide at the base, is fastened with two iron nails; length 26 cm, of which the blade measures 12. A small two-edged meat knife from Iglulik of the same form and material as fig. 96, but only 19½ cm long, 2.3 cm wide, has a sheath of unhaired sealskin, 8 cm long.

Fig. 97 a (Aivilingmiut, Repulse Bay) is a smaller, single edged meat knife with wooden handle, two iron reinforcements which hold the blade, and a suspension hole; it is 19 cm long, the blade being 8½ cm. A knife from the Aivilingmiut differs in size, it being 30 cm long, of which the blade accounts for 12. The handle is of antler. has a notch at the middle and a suspension hole at the butt end. The blade has one edge and is fastened at the base by two reinforcements. let into a socket in the fore end of the handle.

Fig. 97 b (found at Iglulik) is a small, old, single-edged knife. with a thin handle of antler and a narrow iron blade, formed of two pieces rivetted together; apparently it dates from the time before iron became common; its length is 14 cm.

For picking the marrow out of caribou bones they use marrow extractors (saudlûn) usually made of a caribou leg-bone. Fig. 98 (Repulse Bay) shows one of these, 18 cm long; one from Ponds Inlet, 14 cm long, of the same bone, is thin and slightly widened at both ends to a spoon-like, slightly hollowed-out bowl. Broader bone spoons are sometimes used for picking out the brains from caribou heads. Parry[55] figures a bundle of marrow extractors of better manufacture, tied to a needle case, and the marrow extractors which

Boas[56] figures from the west coast of Hudson Bay also show more careful workmanship, being ensiform with dot-and-circle ornamentation and a hole in the rear end.

The sucking tube (tordloaq) is used for sucking up liquids which are difficult to drink, when for example they are full of pieces of ice, etc; when caribou-hunting they are also used for drinking water from flat, ice-covered pools, etc. Fig. 99 (Iglulik) is a sucking-tube of a caribou leg-bone with the ends cut off; 19 cm long. Two others, from Iglulingmiut, Qajûvfik, are of the same bone, 16 and 18 cm long.

An indispensable household utensil is the snow beater (anautaq), with which clothing must be beaten as soon as one comes inside the house, as otherwise the snow will soon melt. Fig. 100 a (Iglulingmiut. Qajûvfik) shows the typical form of snow beater, which is also figured by Boas;[57] it is of wood, 43 cm long, 1.7 cm thick, with rounded edges and a shaped handle with a knob at the end and one shoulder. Four other specimens of the same form have lengths from 40 to 53 cm; on one of them the end-knob is a separate piece, of antler, lashed on. From Repulse Bay we have a snow beater in the form of a thin, crooked branch of antler, 39 cm long, maximum thickness 1½ cm, pointed at one end (Fig. 100 b). For a length of 9 cm the handle is furnished with 28 grooves.

The remaining household furniture includes various boxes, bags. and sacks for keeping tools, clothing, etc. Small toolboxes (qijorqut). wooden boxes about 50 × 15 × 15 cm, are nearly always part of the travelling equipment. Sacks (ikpiarssuk) are used for keeping clothing, pieces of skin, etc.; canvas sacks are mostly used nowadays. Fig. 101 (Ponds Inlet) is a clothes bag of unhaired seal skin; the bottom forms an almost circular piece, 25 × 27 cm; the sides consist of a piece of skin sewn together by a longitudinal seam, about 80 cm high; the upper mouth is edged with a strip, 2½ cm wide, in which are ten holes for a running cord; the sewing (running stitches) is done with sinew thread. Another clothes bag from Ponds Inlet consists of black, unhaired sealskin with the hair-side out; the bottom is in one piece, the sides another and the mouth-edge consists of a 5–6 cm wide strip of light-coloured sealskin; near the bottom the diameter is about 24 cm, at the mouth 15 cm; depth 25 cm. A third clothes bag, from the Iglulingmiut, Ponds Inlet, has its bottom and one side of bladder skin, the other side and the 6 cm mouth-edge of partly unhaired caribou skin; diameter near the mouth 18 cm, at the mouth 10 cm; depth 25 cm.

Bags of bird's foot skin were figured as long ago as by Parry[58] and also by Boas.[59] Fig. 102 (Southampton Island) is a similar bag made of the skin of swans' feet. In the middle of the bottom is a circular, white piece of seal skin, 11 cm in diameter. The remainder of the bottom, which is about 25 cm in diameter, and the sides, consist of six wide strips of swan's foot skin with the claws still on, alternating with thinner strips of white seal skin, drawn through with thin strips of black seal skin, the free ends of which project at the top. Round the rather narrow mouth (about 12 cm in diameter) is a white strip of seal skin, about 5½ cm wide. From Iglulik we have a smaller bag, formed of gull feet; in the bottom is a small piece of white seal skin, 2½ cm in diameter; at the top a strip of seal skin of the same width, drawn through with two black thin strips; the sides are wholly of bird's foot skin. The total diameter is about 12 cm.

From Iglulik we have an oval bag of loon skin with the feathers on, about 30 cm long, 14 cm wide; the mouth is 13 cm long, edged with seal skin strip, 1 cm wide.

Lyon[60] mentions "a large bag entirely composed of the skins of salmon, neatly and even ornamentally sewed together". On Southampton Island I saw a small bag of salmon skin in which were kept pieces of flint for fire striking with steel. A small bag from Ponds Inlet has a bottom of salmon skin with a diameter of 10 cm and sides of bladder skin; the mouth is 8 cm in diameter, edged with a strip of seal skin 1½ cm wide; the depth is 15 cm.

Fire in former days seems to have been mostly produced by the help of two pieces of pyrites (ingnerit) struck against each other; the sparks were caught on cotton grass (supun) or moss; this method is also referred to by Parry.[61] Pyrites occurs fairly commonly in the limestone area. Fire-boring has also been used, however; for this they used a bow (nîun) which made a wooden stick (usuk) rotate rapidly against another piece of wood against which it was pressed. Lyon[62] mentions fire-making "by friction"; presumably he means this method. They are both hardly ever used now, as all have matches or fire-steel. But one must economise with matches; in the house the pipes are always lighted with a stick dipped in oil. ignited at the flame of the lamp.

- ↑ Mathiassen 1927.

- ↑ Cf. Boas 1901, fig. 137.

- ↑ 1824 Plate p. 550. 1.

- ↑ 1879, p. 73.

- ↑ 1901, p. 94.

- ↑ 1907, fig. 208 a (Aivilik), 208 b, d and 209 d (Iglulik), 207 e–f and 208 e (Ponds Inlet).

- ↑ It is presumably due to a misunderstanding that one sees pictures of snow houses in which the spiral ascends in the opposite direction, from left to right (Parry 1824, Plate p. 499, Gilder p. 255, Boas 1888, fig. 492 b); I have never seen a snow house built in that manner and really it would be most unnatural, except for lefthanded builders.

- ↑ See also Boas 1901, fig. 139.

- ↑ Boas 1901, p. 96 writes of the snow house of the Aiviliks: "The snow house differs from that of Cumberland Sound in that the bed platform is not in the rear of the house but at the sides", but this only applies to the large houses: the ground plan figured by Boas 1888, fig. 491 of a snow house of the tribes at Davis Strait might just as well be of the Iglulik Eskimos.

- ↑ 1879, p. 128.

- ↑ 1901, p. 96.

- ↑ 1906, p. 142.

- ↑ 1824, p. 500.

- ↑ Jenness 1922, fig. 13 f.

- ↑ 1824. p. 502.

- ↑ 1879, p. 90.

- ↑ 1888, fig. 531.

- ↑ 1888, fig. 505.

- ↑ 1824, p. 271.

- ↑ l. c., p. 272.

- ↑ 1824, p. 90.

- ↑ Archaeology of the Central Eskimos I, p. 101.

- ↑ 1824, p. 358.

- ↑ l. c., p. 285.