Material Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 5

| Table of contents |

To a nation living such a roving life as that of the Iglulik Eskimos, means of conveyance naturally are of great importance. As a consequence of the lack of permanent habitations. these people are practically always travelling; and, even if they have settled down at a certain place for some time, the struggle for existence makes it necessary for the men to make trips, and indeed sometimes long journeys, lasting several days, in order to find and kill game. Thus travelling is looked upon as a very natural form of existence; it is not regarded as being unusual or troublesome, as a necessary evil to be brought to an end as quickly as possible. If a man at Repulse Bay is seized with a desire to visit a relative at Ponds Inlet and he has sufficient dogs for the journey — it is surprising how few dogs are required — he sets off with his family, makes a halt where there is game for as long as he feels inclined, and then on to Ponds Inlet sometime sooner or later — if not this year, then perhaps next year; time is of no importance whatever. It is this complete lack of respect for time which one often has to contend with while travelling with these people. To travel quickly through a country with so many caribou is an absurdity to them.

In dealing with the means of conveyance of the Iglulik Eskimos it must be realised that the sea is covered with ice nine or ten months of the year; and at any time during the short period of open water the sea may be filled with drift ice which makes any sort of navigation impossible. It will thus be understood that land journeys predominate and, as the country is covered with snow for nine months, it is with the dog sledge that most Eskimo journeys are undertaken. During the months when there is no snow they travel to the interior on foot, man and dog carrying what necessaries are required. In the short period of open water the whale boat and the kayak are used; the latter, which by the way has disappeared from the whole of the southern part of the country, is however rather a hunting accessory than a means of conveyance; the whale boat was only acquired through intercourse with European whalers.

Fig. 42 (Iglulingmiut) is a typical Iglulik sledge (qamutik). The runners (qamutin) consist of whole planks, although the upper edge of one of them is a separate piece nailed on. The length is 3.53 m; height of runners 19 cm, thickness 4–5 cm, distance between them 41 cm. They are shod with whalebone (perraq); the noses of the runners are barely turned up. The cross-bars (naput) are about 70 cm long, 6–18 cm wide; thus they vary considerably, are roughly made, and lashed on to runners with seal-thong. The uprights (napariaq) are formed of a caribou antler with the side branches hewn off: their height above the ground is 78 cm.

To this sledge belongs a draught strap, consisting of a cross-strap which has two loops to go through holes in the runners, where they are held by pieces of antler (tuklerutit), long, pointed at one end. rounded on one side, flat on the other, with a deep. wide groove across the middle in which the loop of the cross-strap rests, whilst a thin cord, tied to the strap, passes over the runner and fastens in a hole in the thick end of the antler toggle; the length of this toggle is about 8 cm. The draughts-strap itself, which runs from the middle of the cross-strap, is 85 cm long and is closed by a buckle of ivory (pardleriaq); this is shown on fig. 43. It measures 8.8 × 5.6 × 3.9 cm, oval in cross-section, pierced longitudinally by a cylindrical hole, through which one end of the strap passes; its loop drops over a stud, carved like the head of a seal, at one end of the buckle. whilst in a similar one at the other side of the cavity there is a hole in which the other end of the strap is fastened. The buckle is decorated with dot-and-circle ornamentation.

Another sledge (Aivilingmiut, Southampton Island) has runners. of whole planks, 4,9 m long, 18 cm high and 5 cm wide; the distance between the runners is 46 cm; at the front they bend up a little, the nose-ends being 14 cm above the upper edge of the runners; the upper part of the nose consists of separate pieces of wood, 75 cm. long, nailed on. The cross-bars begin 90 cm from the nose; there are 17 crossbars (originally 19), 69–70 cm long, 5–18 cm wide and 2½–5 cm thick. Shoeing of whale bone, 5–9 cm wide.

A third sledge, from Ponds Inlet, has runners 2,70 m × 22 cm × 5 cm, distance apart 52 cm. The first cross-bar begins 60 cm from Image missingFig. 43.Pieces for holding the draugth-strap. 1 : 2. the nose, which is not bent up at all. There are 11 cross-bars, 76–84 cm long, 7½–14 cm wide. Whale bone shoeing, six shoes in all. of which two are on one runner, four on the other; the width of the shoes is 8 cm, thickness 1 cm, although towards the nose. it is about 2 cm.

The biggest sledge I saw in Repulse Bay had the following measurements: length 5,9 m, height of runners 20 cm, thickness 6½, distance apart 48 cm; 15 crossbars, 78–91 cm long. The runners were shod with iron and there was also iron shoeing on the upper side of the noses extending as far as 21 cm from the tip.

The usual size of a travelling sledge is 4½ to 5 m long, width between the runners 40 cm.[1] On shorter trips, especially on the sea ice, very small sledges are used. just big enough to hold one man. A sledge of this kind, from the Aivilingmiut, used especially in utoq hunting, is 1.07 cm long, height of runners 8½ cm, thickness 2.2 cm, distance apart 36½ cm; the noses are not bent up; distance to the first cross-bar 24 cm; five cross-bars, 7–8 cm wide, 43–49 cm long, each cross-bar having four pairs of notches; eight whale bone shoes, 4½ cm wide, fastened on with iron nails.

Fig. 43 b (Ponds Inlet) is a bone piece for holding the draughtstrap, 6.6 cm long, of the same type as that described above. Two buckles, of the same shape as that described, from Iglulik and Repulse Bay, are of antler, 7.4 and 5.8 cm long.[2] Besides this form. ordinary bone toggles (sanariaq) are also used for connection the trace.

Whale bone is used for preference for shoeing sledges, as it glides easier than iron in severe frost and holds the mud shoeing better. Old whale bone, mostly taken from house ruins, is preferred to new bone, as the latter is saturated with fat and thus cannot hold the shoeing. An exceedingly important feature about the sledge of the Igiulik Eskimos is the mud shoeing. Peaty mud is taken in summer from the bottom of a small pond; it is more difficult to get it in winter when it has to be chopped up, thawed and cleaned of stones and lumps; sometimes it is kneaded with a board whipped with a thick seal thong, about two centimetres between each spiral winding. When the mud is to be laid on in the autumn it is thawed, mixed with water and thoroughly kneaded until it is of uniform consistence; it is then shaped into balls of about the size of a fist and these are laid along the runners and spread out into an even, 5–6 cm thick layer which, in order to hold better, is also laid a little way up the sides of the runners; this makes the runners about 10 cm wide at the bottom. With a knife (or a plane) the underside of the frozen mud is now smoothed flat and on top of this is laid the ice shoeing, water being poured on a piece of bear skin, which is quickly rubbed time after time over the mud surface until there is an even layer of ice over the whole of the runner, about two cm thick; I have once seen a brush of bear hair used in applying the water. Ice-shoeing can also be made of snow which has newly drifted together; it is dipped in water and smoothed out. A little salt or urine in the water makes the ice shoeing strong.

This process of putting mud shoeing on a sledge often lasts several hours and is by no means a pleasant task, as the mud must be laid on with the bare hands. Despite the considerable increase in weight thereby given the already heavy sledge, this shoeing is of great advantage in the cold period, when it does not so readily break off and the sledge is made to run much more easily. When driving over pack ice this shoeing lasts surprisingly well; only over stones does it readily break, for which reason care must be taken to avoid stones when travelling across country. If a large piece of the mud shoeing is lost and cannot be found, it is a great calamity which often involves an immediate pitching of camp. If the piece can be found, it is often lashed on by boring holes through it; otherwise an attempt must be made to repair it with moss fibre mixed with snow. and urine, or blood and gut, porridge, or any other material at hand. I have occasionally seen blood and caribou gut, the contents of caribou gut and stomach and caribou liver used as shoeing without mud; but it was not so durable and the dogs gnawed it. In order to be able to renew and repair the ice shoeing at any time they usually take a small water-bag, which the woman carry in the backpouch if they have no small children. Fig. 44 (Iglulik) is a water-bag of this kind, of bearded-seal skin, joined in one seam along one side and the bottom, with a fairly narrow neck round which a cord can be tied; 36 cm long, and, in its present flattened state, 18 cm wide. A similar water-bag from Ponds Inlet is of five pieces of bladder skin sewn together, 27 cm long, 14 cm wide, but at the mouth only 7 cm wide.

In the autumn of 1922 the Eskimos on Southampton Island began to use mud shoeing in the middle of November; in the spring of Image missingFig. 44.Water-bag. 1922 I saw it used until 29th May, in 1923 until 21st May. When travelling late in spring the mud shoeing must be protected against the strong sun by means of a piece of skin hung down from the sides of the sledge to keep it in the shade, while the noses of the runners are wrapped in skins.

Sometimes when travelling on land a layer of walrus hide is laid under the runners instead of mud; the hide is frozen fast and the hair cut off, thus making the under side of the runners smooth; the ice-shoeing is then laid on this. Walrus hide does not last so well on ice as peat, however.

In former times, when wood could not be procured, sledges were made mostly of whale bone. Lyon[3] describes the sledges at Iglulik: ". . . . made of the jaw-bones of the whale, sawed to about two inches to a foot. These are the runners, and are shod with a thin plank of the same material; the side-pieces are connected by means of bones, pieces of wood, or deer's horns, lashed across with a few inches space between each, and they yield to any great strain which the sledge may receive. The general breadth of the upper part of the sledge is about 20 inches, but the runners lean inwards and therefore at bottom it is rather greater. The length of bone sledges is from four feet to fourteen. Their weight is necessarily great; and one of moderate size, that is to say, about ten or twelve feet, was found to be 217 lbs." Parry[4] mentions an 11' sledge which weighed 268 lbs and that the runners were often made of "several pieces of wood or bone scarfed and lashed together, the interstices being filled to make all smooth and firm with moss stuffed in tight and then cemented by throwing water to freeze upon it". Hall,[5] too, mentions a whale bone sledge from Repulse Bay.

Sledges with runners of skin are sometimes used. In summer when the young men go caribou hunting in the interior with their families and their chattels, they do not take a sledge with them as a rule; it is too troublesome to carry about. And then, when there is sufficient snow for sledging, they make sledges of caribou skins and antlers. On Southampton Island, in the winter of 1922–23, I saw three such sledges. One was made of one caribou skin, divided longitudinally and the halves folded lengthwise with the hair side. inwards and then frozen together in that form; the nose was bent up a little. The dimensions of the runners were 2.0 m, 22 and 9 cm; their distance apart 55 cm. Four pieces of antler and one piece of wood were used as cross-pieces. The runners were shod with mud and then ice, formed by laying snow in water and then rubbing it on. This sledge was so light that a man could carry it with ease. Another sledge was made of two caribou skins. On this the dimensions of the runners were 3 m, 20 and 10 cm, distance apart 40 cm; mud shoeing; six cross-pieces; the runner-noses slightly upturned. These sledges are fairly durable; if only the dogs are prevented from eating them they can last a whole winter; they have difficulty in standing pack ice, however. Sometimes the runners are stiffened by a layer of mud or a few caribou leg bones being laid inside them.

In earlier days, when wood was more scarce than it is now, skin sledges were more common. A man about 65 years old was able to remember that in his childhood there were only two wooden sledges at Iglulik; the other men made sledges of walrus hide in winter: two pieces were folded over with wet snow between and frozen together into very hard runners; walrus penis-bones were used as crosspieces. When they returned from the caribou hunt in autumn the seal-skin tents were often made into sledge runners, antlers being used as cross-pieces; a sledge of this sort was called qerqetitaq. The earlier writers also refer to sledges with runners of seal and walrus hide.[6]

On certain occasions when they had no other sledge or the snow was too soft for them, a kind of sledge without runners was used, often simply a caribou or bear skin, to which the dogs were harnessed. In October 1922 the meat of a whole and a half caribou was carried to the house at Hansine Lake on a caribou skin (uniútaq), which glided easily over the smooth ice of the lake drawn by five dogs. At Iglulik, when there was soft snow, a sledge of walrus hide without runners (atdleraq) was sometimes used; Lyon[7] writes: "we sometimes saw a person who had but one or two dogs, driving in a Image missingFig. 45.Trace and harness. little tray made of a rough piece of walrus hide, or a flat slab of ice, hollowed like a bowl". At Iglulik they sometimes used a sort of toboggan of this kind, made of baleen joined together (also called uniútaq); it is presumably one of these that Lyon[8] means when he says that a man made a substitute for a sledge "by plaiting whalebone, with which wretched contrivance they would have attempted to set out".

The sledge load is laid upon skin; if there is meat or blubber in the load, it is packed in sealskin; otherwise caribou skin is used. The skins under the load have the hair side downwards; over the load is laid a covering of skins with the hair upwards. The load is then lashed firm with the lashing thong (napuliut), a strong seal-thong which is passed round the ends of the cross-pieces and Dulled very tight. When there are rails on the sledge, these support the load very considerably.

To the draught-strap are fastened the traces (ipiutat), to the other end of which is fastened the harness of the dogs (ano). Fig. 45 (Ponds Inlet) shows a trace and Image missingFig. 46.Method of fastening the trace buckle. harness; the trace is of seal-thong, 4.6 m long, divided into two pieces which are held together by a loop and a small toggle (sanariaq) of musk-ox horn, 7.3 cm long, At the rear end is a trace buckle (orseq) of whale bone of the usual shape with two holes, one large and one small, drilled in the same direction; it is 6.5 cm long. The method of fastening the trace buckle to the trace is shown in fig. 46. The harness is of unhaired seal-skin straps, about 2½ cm broad; it consists of two loops round the fore-legs of the dog, meeting in a single strap at the front and sewn together at the rear at the spot (on the dog's back) from which the trace starts; a short cross-strap connects these two loops at the back of the dog's neck.

Another trace is 6.0 cm long, has a trace buckle of antler, 5.0 cm long; the trace is not divided and thus has no toggle. A third trace is

Fig. 47.Leader dog with fringe-harness.

5.5 m long and has a buckle of antler, 5.1 cm long. Both are from Ponds Inlet. A set of harness from Qajûvfik has a 3.7 m trace and a buckle of antler, 4.3 cm long, with only one large hole: a cross of red cloth is sewn on the harness to show that the owner is a Christian; no toggle.

Fig. 47.Leader dog with fringe-harness.

5.5 m long and has a buckle of antler, 5.1 cm long. Both are from Ponds Inlet. A set of harness from Qajûvfik has a 3.7 m trace and a buckle of antler, 4.3 cm long, with only one large hole: a cross of red cloth is sewn on the harness to show that the owner is a Christian; no toggle.

Sometimes the leader dog, and now and then the "boss", are distinguished by having harness with fringes (Fig. 47). A set of this kind, from Iglulik is of black, unhaired sealskin; the straps are formed by folding over a broad strip; they are now 3½ cm wide. On each loop is sewn a piece of hairy sealskin, 13 cm long, cut to form fringes 30 cm long. The upper part of the trace, 60 cm long, is fastened to the harness by means of a rather heavy trace-buckle of ivory, 7.1 cm long.

The trace buckles are often distinguished by their size and, especially in the Iglulik district where there is plenty of ivory, are of considerable weight — which is said to increase the drawing powers of the dogs. Fig. 48.2 (Iglulik) is a trace buckle of ivory, 7.6 cm long, 2.9 cm thick; one from Pingerqalik is still heavier (9.4 cm long, 3.8 cm thick). Sometimes, however, buckles are not used at all, but simple loops. A separate toggle is seen Fig. 48.3.

Fig. 48.1 (Iglulik) shows a walrus tusk carved to form three trace. buckles and a toggle for the draught-strap; the various pieces are not finished and are still joined together. A block, found at Yellow Bluff, exactly like European blocks, carved in ivory, is 7.0 × 4.4 × 2.9 cm; it has presumably been made according to the European pattern and used for the draught-strap.

The whip (iperautaq), which is used when sledge-driving, consists of a short handle of wood or bone (ipo) and a long lash of seal-thong (iperautaq); the rear end of the lash is very thick and formed of several thongs plaited or sewn together. Fig. 49 (Aivilingmiut) is a whip of this kind. The wooden handle is 29 cm long; the foremost 12 cm of it are closely wound with thin strips of seal-thong, one

of which passes round the end of the handle and back again. The rear 75 cm of the lash are formed of closely plaited, thin thong, round, about 2½ cm thick, decreasing evenly in thickness towards the fore end. The rearmost, thick part runs into another piece, 23 cm long, consisting of two thick strips of seal-thong, 1½ cm wide, sewn together, and then follows a length of single thong, decreasing in width from 1.3 cm to a quite thin end, 8.2 m long. Thus the total length of the whip is 9½ m. The thick, rear end of the lash may also be formed by laying a number of wide thongs over each other and sewing them together, or of a broad thong rolled together and sewn. Lyon[9] says that the whips have a handle of one foot and a lash of 18–24 feet.

The dogs are of the usual Eskimo breed and do not differ much, in appearance, from the Greenland dogs. There is, however, a considerable difference in the size; some Eskimos pay especial attention to the breeding of big dogs, as for instance Ilupalik and his family at Ingnertoq where I saw the biggest dogs. The colour varies greatly: white, black, yellowish, reddish-brown and the greyish-brown colour that is called singarnaq.

As a rule the Iglulik Eskimos have not many dogs; only a few have teams of ten dogs or more, even in years when distemper has not done great ravage; as in 1922–23. The usual number owned by a family is four to six; on journeys it is therefore a common occurrence that two families share one sledge. The reason why they have so few dogs is the difficulty of procuring food for them, especially during the caribou-hunting season. In this respect the Iglulingmiut themselves are in the best position as they oftenest have big stores of walrus meat; and as a consequence it is among them that one finds the biggest and best dog-teams.

As Parry[10] expresses it. the dogs are treated "as an unfeeling master does his slaves; that is, they take just as much care of them as their own interest is supposed to require." Only as pups are they treated well; this, however, is necessary if they are to live at all. A small snow or ice house[11] or a little shelter of stone is often built for a bitch with pups; or it may be taken into the dwelling house where the pups remain during the first few weeks and are fed on the best — if there is food to give them, Bitches with young sometimes have the lower part of the body protected by a piece of skin. One of these, from Igluliks, Qajûvfik, is of caribou skin, 36 × 36 cm, and at the edges has a number of straps, mostly of sealskin, and one or two longer cords for tying. The pups are not very old, however, before the children get them to play with and they treat them by no means gently, put harness on them and thrash them with toy whips, sticks, etc; it hardly ever happens, however, that the pups bite the children. If the pups are to travel while still small, they are put into a caribou-skin bag which is fastened on to the sledge; if they are big, they are tied on without being packed in. When they are about two months old they can already begin to be harnessed to the sledge; even if they cannot do much good, they can become accustomed to the harness and to obey; they often have to be whipped terribly before they learn this.

The fully grown dogs are always very harshly treated, seldom get more food than will just keep up their strength, often have to through long periods of hunger. are thrashed and kicked at every opportunity and are often whipped in a most frightful manner; but they are an uncowable breed, who remain cheerful in spite of nearly everything.

Everything eatable is used as dog feed. The best is the solid, fat walrus meat; but seal, narwhal and white-whale meat and blubber are good too. Caribou meat, especially of lean animals, is a much poorer feed; enormous quantities of lean caribou meat are necessary to keep up the strength of the dogs in the severe cold of winter. But it is by no means always the case that the dogs can be fed on meat; more frequently they have to be content with refuse of various kinds which man despises: the entrails of seals and other animals, walrus hide, the contents of the stomachs of caribou, and the quantity divided among them is often quite insufficient. In summer, when no work is required of the dogs, they are not fed at all as a rule, but have to roam about and find food for themselves on the beach or around the settlements.

As an example of how the dogs are fed when food is scarce I will describe my experiences on Southampton Island in the winter of 1922–23. Our host, Angutimarik, had a good dog team of ten dogs and two pups: another man, Saraq, who lived with us, had six dogs and a number of pups. All the summer the dogs had roamed about the country round Duke of York Bay without being fed; when we sailed from Kûk on September 6th in boats we saw dogs running along the shore at Comers Strait. When we got back to Kûk on September 13th most of Angutimarik's and Saraq's dogs had arrived there and, for the first time since summer, they were then fed with walrus meat. On September 29th several seals were caught, and again the dogs received a good feed; during the two weeks that had passed they had showed signs of being very hungry, for instance the pups had eaten most of our tent guys (of rope!). On October 4th the dogs got the opportunity of eating the refuse remaining when the tents were moved; there was not much that was eatable, but a few bones at any rate, fat-sodden pieces of skin and a little grease to lick off the stones. While at Hansine Lake: October 8th they were fed on the leavings of our meals of salmon during the last four days. October 9th a caribou was wounded, which the dogs pursued and ate. October 12th fed again with salmon leavings and a little liquid blubber poured into a trough of ice. October 18th again fed with a little fish oil containing lumps of blubber. October 21st fed with salmon leavings and picked caribou bones; several of Saraq's pups now dead from hunger.

The journey to Kirchhoffer River (Angutimarik's team alone): October 29th, fed on a seal skin in which there had been blubber, some salmon and caribou bones. October 31st fed on a little oil with lumps of blubber. November 9th a dog died of hunger and several others were very weak. November 10th, fed on half a lean caribou. November 13th, fed on two whole caribou. November 15th, fed on a caribou and a half. At Darkness Lake, Kirchhoffer River: November 17th, fed on a caribou. November 22nd, 23rd and 29th fed on caribou meat; the dogs, at any rate the more sturdy ones, begun to improve.

Thus Hall[12] is not far wrong when he writes: "The Iwillik people, in hard times, feed their dogs once a week." If there is plenty of meat the dogs are usually fed every other evening when on winter journeys; each dog then receives 1–1½ kilogrammes of meat; during halts they are only fed every third or fourth day.

The dogs are often fed in the simple manner that the meat is cut up and thrown to them promiscuously; but as this means that the big, powerful dogs always get more than their share, two to four dogs are sometimes taken into the house and allowed to eat from a heap of pieces of meat lying on a skin on the ground; if they are taken singly, the process is too slow; often a dog becomes so bewildered at coming into the house to such abundance that it forgets to eat; it is then merely kicked out again when time is up. At Iglulik we once saw a special dog feeding-box of walrus skin. frozen into shape. At Pingerqalik in February, 1924, where there were lots of food, the dogs were fed in the houses until they could eat no more and went outside of their own accord.

It will be understood that in the cold winter time the dogs are nearly always hungry and they sneak about trying to get a bite more than their ration. As a consequence, everything eatable — meat, skin clothing, seal-thongs, etc. — have to be hidden inside the houses or placed on a scaffolding where the dogs cannot reach them. Sledge lashings, traces and harness are eaten if one is not careful. Human faeces are regarded as a great delicacy, a circumstance which can involve much unpleasantness if one is not armed with a whip or a stick. If there is no door to the snow house — not all families possess a wooden door — a watch must constantly be kept in order that the dogs may not break in and eat the meat, the blubber in the lamp, and so on. If they try to make their way in they are greeted with severe blows with the snow-beater, a harpoon, axe, or a special implement — a whip without the thin lash, a weapon which can distribute terrible blows. A house-whip of this kind from Iglulik consists of a handle of wood, 21 cm long, the butt end of which is wound, first with plaited sinew-thread, then with seal-thong, which forms a strap for hanging the whip up; then there is a very thick lash, 63 cm long, made of rolled sealskin, sewn through and through with thick seal-thong; at the base the thickness is 3 cm, at the end 1½ cm. If the dogs break in at night — an experience I have had twice on Southampton Island — it is most unpleasant. A dog manages to get the door open and, in a second, the house is overrun with dogs; they bolt in, overturn the lamp and put the room in darkness, snap up everything eatable. The Eskimos, who have to creep about naked on their rugs, become quite desperate and strike out at the dogs with anything they can get hold of, axes, snow-knives, snow-beaters. the house soon becoming a battlefield resounding with blows, tremendous yells and the scolding of the Eskimos.

But it never occurs to the dogs to resist and bite; when they are hungry they are cowardly; but if they have eaten their fill and are in good condition, they may, in their playfulness and boldness, be a little snappish[13] without meaning any harm by it. It is astonishing to see a big, powerful dog tolerate being beaten by a three or four year old boy without so much as showing its teeth. Even during the worst periods of hunger the dogs never think of turning against human beings.

All dogs have names. These either have some meaning which refers to certain of the dog's peculiarities or are "only names"; Parry[14] says that the dogs are named after friends and acquaintances, but this is not the case, now at any rate. The names of a sledge-team from Iglalik were: Iglulingmiutaq — the one from Iglulik; Qernerkuluk — the little black one; Qingmikuluk — the little dog: Tunuserut — the one from Admiralty Inlet; Tabakert — tobacco; Qernialuk — the big black one; Nâkateq — the one who does not get what he goes for; Kâktoq — the hungry one; Taguarbik, Ququngmiaq, Paqbiseq, Ajakaluk — "only names".

A team from Southampton Island was called: Pualualik — the one with mittens on; Qerquaq — seaweed; Kâkbik (bitch) — needle case; Tikivik — thimble holder; Atuarsijoq — the pathfinder; Oqsoreaq — quartzite; Aterdluk — the one with the bad name; Kilingajoq — the food which a tabooed woman must cook for herself; Qernerluk — the little black one; Alaqtalâq — the one with no harpoon line; Qijuk — wood; Akudlojoq — "only a name".

In every dog-team there is a leader and a boss. When driving the leader has the longest trace and leads the way according to the calls of the driver. The boss is the strongest dog, who keeps the team in order and sees that every dog is in its place; in addition, it is as a rule the only dog that is permitted to copulate, none of the others being allowed to approach the bitches in the team. It sometimes happens that the boss is leader too; but as a rule the latter is a smaller, intelligent dog, often a bitch. The traces are of various lengths; in a team at Repulse Bay they varied from three to eight metres; pups, and poor dogs which require frequent use of the whip, have the shortest traces.

The teams of the Iglulik Eskimos have not that permanent, exclusive character of, for instance, those of the Polar-Eskimos. The reason is that only few Iglulik Eskimos have a complete team; almost every time they are going on a journey they have to borrow dogs from others, and of course they must lend their own dogs out on occasion. This constant mixing of the teams is not to their good and involves a certain slackness and disorder, and often violent fights between the various components of the team.

When driving the driver sils at the front of the sledge with his legs hanging over its right side and the whip hanging down so that the lash trails on the snow — or more frequently he walks alongside the sledge. He indicates the direction to the leader by calling: to the right — O-å-a, o-å-a; to the left — Harra — Harra; stop — å —a. (Lyon:[15] to the right — wah-aye. a-ya. whooa; to the left — a-wha, a-wha, a-whut. Parry:[16] Stop — wo. woa). To encourage the dogs they have a number of various sounds, many of which are difficult to reproduce. The usual advance signal is a peculiar gutteral sound, each of the syllables having pronounced stops: au — ja — ao, a sound which even all Eskimo women cannot utler. Other calls to increase speed are: ut-ul or utog, utoq, tukto, nanogq, inerssuit, ajukaha, the first pronounced as if almost tearing the throat, the latter like a very slender, whistling sound. If these signals do not have the desired effect, the whip comes into play and punishes the lazy ones. When strikling a blow with the whip the handle is brought forward quickly and then back suddenly, or the arm describes a circle: forward, up, back, down. If the whip is used with sufficient force it can give a terrible blow which rolls the dog over, A skilful dog driver can with certainty hit every dog in the team; if he should happen to strike the wrong one it will often throw itself upon its neighbour and a wild fight ensues which can only be brought to a stop by means of a severe use of the whip, and of course the sledge is stopped. Most of the Iglulik Eskimos are exceedingly poor dog drivers; they shout at the dogs incessantly and at the same time use the whip quite mechanically, as when one is rowing a boat; and as a rule the whip strikes those nearest and these howl continually; as a consequence they are quite low spirited whilst the other dogs plod calmly along, untroubled by the driver's shouts and the whip; sometimes he will then rush forward and beat with the whip-handle some dog or other which he has picked out. It is seldom that a leader is thrashed once it has been trained.

If the dogs are tired the sledge comes to a stop on the slightest provocation, as soon as it meets a little additional resistance or the driver ceases his bawling for a moment; the dogs lie down and only a liberal application of the whip will make them get up again. If the sledge has stopped, it is started again by gathering up the traces and drawing them tight; then when the dogs advance again at a call the traces are dropped suddenly the resultant jerk sets the sledge going again; a kick at the sledge is often sufficient, however. If there are tracks which the sledge can run in, this always facilitates driving considerably and wide detours are often made in order to follow a track; if there are no tracks, the most skilful driver will often go first with the best team. If the dogs see anything dark lying in the snow in front — most often dog excrement — the speed increases tremendously in the hope that it is something eatable. The same thing happens when caribou or bear tracks are met with and it is often a difficult matter then to keep the dogs going in the right direction. If the sledge is to stop, the signal is called and all the dogs are made to lie down by letting the whip drop gently on to them.

When loaded, the sledge is steered by the driver who walks on the right of it at the front and, with his left hand, holds the lashing-thong; if there are many stones or the terrain is difficult, the wife or another man walks on the left side, holding the same thong. When the going is particularly difficult, as on pack-ice for instance, one usually walks on ahead and shows the dogs the way, two steer the sledge and one or more push behind. Ice bare of snow is avoided, as the ice shoeing breaks easily on this; on bare sea-ice the shoeing readily becomes soft owing to the salt. When driving down steep banks, the two who hold the lashing-thong brake the sledge. bracing their feet against the snow; the dog-team is kept out to the side by signals in order to avoid being crushed by the sledge if it should get up too much speed. Klutschak[17] writes that when negotiating steep descents the dogs are out-spanned, and the sledge is set in motion, steered by a person on either side; a rolled line of walrus hide, held under the runners, serves as a brake. When driving light, the sledge is steered by the driver who rests on his left knee well forward; he then steers the sledge with his right foot round ice hummocks, stones, etc.

How much a dog team can pull and how quickly, depends upon many circumstances. Parry[18] says that ten dogs one day in June pulled a sledge with 1200 pounds a distance of 40 miles, but this is

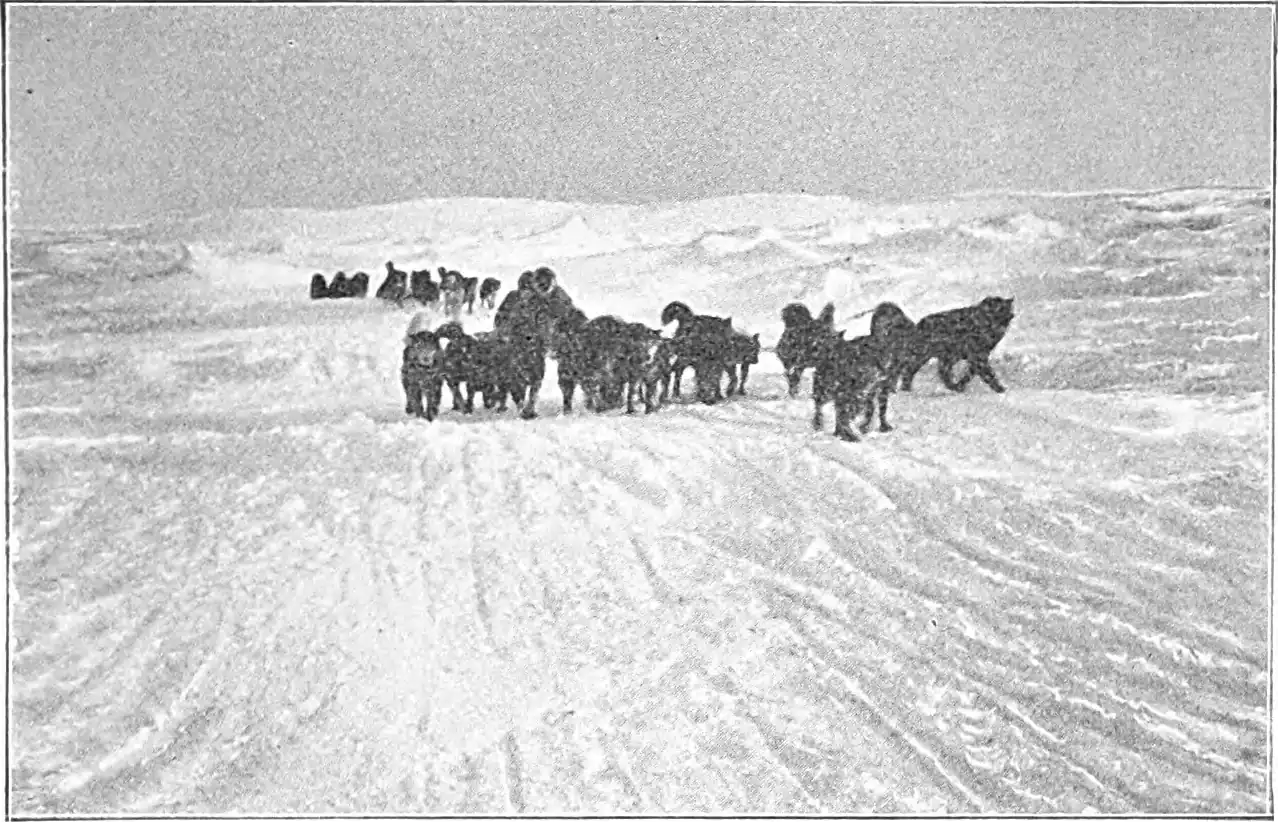

Fig. 40.Two big dog teams. Danish Island.

by no means the norm. Most of the Iglulik Eskimos' sledge journeys proceed at no greater pace than that a man on foot can easily keep up; in fact it is more often the case that the driver has to walk alongside the sledge, and, what is more, the wife frequently has to walk ahead. An average speed of three to four kilometres is fairly general on winter journeys, and this corresponds to a day's journey of 25 to 30 kilometres. In spring, when there is not much snow on the ice, when the days are longer and it is not necessary to build snow houses at night, day's journeys of 40 to 50 kilometres are common. When we moved across the middle of Southampton Island in November 1922 with a load of about 600 kg, drawn by ten hungry dogs, the average speed was barely over 2½ to 3 kilometres, even when everybody walked, and we rarely advanced more than 20 kilometres a day. I have seen a sledge team of 18 powerful dogs, pulling a big Iglulik sledge with two families who were going to Repulse Bay on a trading visit; but I have also met a very unpretentious sledge turn-out — a half-grown boy with a little sledge, drawn by a half-grown dog and a tiny pup. If the load is too big in proportion to the number of dogs, the men and women have to pull 100, a seal-thong being made fast to the sledge in the form of a loop and put over the breast. On short trips in summer there is hardly any limit to the number of people who can be loaded on a sledge. From Kôroqdjuaq to Button Point at Ponds Inlet (4 km) I saw six dogs pull six people, and 9 dogs pulled 14 people across Repulse Bay.

Fig. 40.Two big dog teams. Danish Island.

by no means the norm. Most of the Iglulik Eskimos' sledge journeys proceed at no greater pace than that a man on foot can easily keep up; in fact it is more often the case that the driver has to walk alongside the sledge, and, what is more, the wife frequently has to walk ahead. An average speed of three to four kilometres is fairly general on winter journeys, and this corresponds to a day's journey of 25 to 30 kilometres. In spring, when there is not much snow on the ice, when the days are longer and it is not necessary to build snow houses at night, day's journeys of 40 to 50 kilometres are common. When we moved across the middle of Southampton Island in November 1922 with a load of about 600 kg, drawn by ten hungry dogs, the average speed was barely over 2½ to 3 kilometres, even when everybody walked, and we rarely advanced more than 20 kilometres a day. I have seen a sledge team of 18 powerful dogs, pulling a big Iglulik sledge with two families who were going to Repulse Bay on a trading visit; but I have also met a very unpretentious sledge turn-out — a half-grown boy with a little sledge, drawn by a half-grown dog and a tiny pup. If the load is too big in proportion to the number of dogs, the men and women have to pull 100, a seal-thong being made fast to the sledge in the form of a loop and put over the breast. On short trips in summer there is hardly any limit to the number of people who can be loaded on a sledge. From Kôroqdjuaq to Button Point at Ponds Inlet (4 km) I saw six dogs pull six people, and 9 dogs pulled 14 people across Repulse Bay.

One can only drive in the dark when there is a track to follow. At Kûk on Southampton Island a man was on White Island for blubber at the latter end of October; to enable him to find his way back a "beacon" was placed outside the house — a big lighted bunch of moss saturated with blubber, placed in a small bowl and surrounded by a sheltering wall of snow.

When a halt is made on a journey and a snow house is to be built, the dogs are usually let loose, as they rest better without harness. A consequence of this is that everything eatable, skin clothing, meat, thongs, etc. have to be taken into the house and the sledges placed on high erections of snow. It happens, however, that to avoid this the dogs are tied, either to a stone or a board which is buried deep into the snow, or to an eye in the ice, formed by hewing two holes obliquely towards each other until they meet at the bottom.[19] Or muzzles (siguqaut) are put on the dogs. A muzzle from Iglulik consists of a sealskin band, 3½ cm wide. 24 cm long, sewn together into a ring: at a distance of 7 cm from each other two seal-thongs are sewn on to one edge of this band, 29 and 39 cm long, and can be tied at the back of the dog's neck.

If the dogs are well fed it does not affect them, even in the most. severe cold, to sleep curled up in the snow. In case of a snow storm, they make their way into the "ante-room" of the house. But if they are thin and hungry, they shiveringly creep together, often in big clusters. trying to warm each other.

In spring, when the ice begings to melt, its surface is turned into fine needles which quickly make the dogs' paws bleed. The dogs are then furnished with dog-boots (qingmit kangmê). Four of these, from Qajûvfik, are oblong pieces of sealskin, unhaired, 24–28 × 9 cm; in the centre of each are two holes side by side for the claws, and in each of the four corners there are holes through which a thin sealskin cord is drawn to tie them with. Fitting boots on the forty or fifty paws of a big team is a task which requires great patience and can give great trouble and cause much delay.

If a dog is inclined to run away, one of its fore legs is tied to its neck by means of a seal-thong, as will be seen on Lyon's[20] picture from Winter Island. The dogs do not bark, they howl; when a sledge approaches a settlement or something else attracts the attention of the dogs, they start to howl and at once all the dogs in the settlement join in a most disharmonious concert of shrill and deep voices blended together and only dying away gradually.

At Iglulik, the dogs used for walrus hunting often have their tails cut off, leaving only a small stump big enough to put the tip of the nose under the reason seems to be that often when the dog jumps over a crack in the ice its tail trails in the water and thus becomes filled with ice and obstructs the dog's movements. Another custom which I saw at Iglulik and which was said to have come from Ponds Inlet (where I did not see it, however) was to clip the dog's hair at the back of the neck "to prevent them suffering too much from the heat in summer".

As will have been gathered from the foregoing, the winter journeys of the Iglulik Eskimos require great physical strength. One must accompany the sledge from morning till night, often walking the whole way, frequently in soft snow, wrestle with the heavy load in pack-ice or over stony or uneven terrain, clear the traces and at the same time continually keep the dogs in hand so that they do not strike out or laze. The wife must assist to the best of her ability, help to unravel the traces, help to steer through pack ice or over difficult country, often run in front to show the way; the women are often just as good drivers as the men. When darkness descends there still remains a good lot to do; camp has to be pitched. The snow house must be built, the sledge-load opened up, meat and skin clothing must be stowed away, the sledge placed on a snow heap; the dogs must be released and fed; the house must be made ready inside, the lamp lighted, ice has to be fetched for melting and, finally, food has to be cooked. Three or four hours may easily pass by from the moment when the sledge stops until the family, their stomachs full of boiled meat, can lie down naked under the sleeping rugs. In the morning, too, a couple of hours pass before a meal has been eaten (usually only frozen meat), the sledge loaded, the sledge-runners iced, the dogs caught and in-spanned. During the day several brief halts are made — rarely more than half an hour — during which men and dogs rest, munch a little frozen meat or try to obtain water by hewing a hole through the ice over a lake. But if there is game: caribou, bear or seal, a halt is usually made at once, and a successful hunt often involves a stay of several days. If the food is all eaten and hunting is bad, hard times arrive with hunger for man and beast. Hungry dogs are much more difficult to drive than satisfied ones, and they make the journey more difficult by the fact that whenever there is an opportunity, they threw themselves at the sledge and devour everything eatable on it; if there is a danger of this happening, there must always be one person at the sledge when it stops. The Eskimos, Image missingFig. 51.Pack-bag for dog. however, bear all these trials and troubles with astonishingly good humour and look upon it all as the most natural thing in the world.

In summer, when the country is bare of snow, the dog sledge cannot be used. The Eskimos understand how to make their dogs useful in another manner, however, as they teach them to carry burdens. On the dog's back is placed a pack-bag (nangmaut). Fig. 51 (Iglulingmiut, Adderley Bluff) is one of these pack-bags, made of caribou skin, from which most of the hair has been removed with an ulo; the hair side is turned outwards. At the edges of the large opening in the middle there are holes for the running-cords; on one side these holes are made in a strip of sealskin sewn on separately. The bag measures 87×48 cm. Another pack-bag from Southampton Island is intended for level terrain. It is of caribou skin, scraped quite thin and transparent, 78×45 cm, and in the middle of one side-piece has an opening, round, about 20 cm in diameter, in the edge of which are holes and loops for a running. cord; on this specimen, too, some of the loops are on a separately sewn-on strip of sealskin. The cords on the pack-bag are tied round the dog's neck and breast. In many cases, however, the pack is fastened directly on to the dog's back, care being taken that the burden is divided into two heavy masses which can hang down the animal's sides, fastened with a girth over the back.

Both Parry[21] and Hall[22] mention that the dogs carry burdens in "saddle-bags"; Parry says that a good dog can easily carry 20–25 pounds; I have seen powerful dogs carrying at least twice that weight, however.

It is particularly during removals and journeys while out caribou hunting in summer and early autumn that packdogs are used. As a rule the Eskimos themselves have to carry heavy burdens on these journeys; Hall[23] refers to journeys of five miles with burdens of 100–125 lbs.

On October 4–5th 1923 we moved with two Eskimo families from Kûk to Hansine Lake on Southampton Island, a journey of 15 kilometres. which took us two days. It was a long and laborious carry. At 5.30 am we broke camp, packed and distributed the loads among seven persons and 20 dogs. Only one of the dogs had a proper pack-bag, two bags of sealskin joined by a piece of the same skin and hung over the dog's back. All the other dogs had harness on, and to this their loads were tied, two cords running from the pack round underneath the animal. One dog carried the tent-sheet (for the sealskin tent; weight at least 25 kg) and two small wooden posts; another a fur coat and two big tent poles which it dragged behind it; a third had a lot of meat and blubber wrapped up in skins; a fourth had a bag and a small box containing sundries, a fifth a bag of clothing, a sixth two caribou skins, and so on. Even the big pups had to carry something, if only an enamel cup on a cord round the neck. All the adult persons carried heavy burdens, which were scarcely less than 50 kg; these loads were usually so arranged that a strap passed across the breast and another across the brow. Only slow progress was made; at every moment the caravan had to stop because a dog had slipped its load, had lain down when its load had become disarranged; two started to fight, one began to eat its load, another got caught on two stones, and so on. On the first day we marched from noon until 5.30 pm but had to camp then owing to the darkness; the next day we went on another four hours before we reached our destination. A dog was then missed and a man had to go back to look for it; it had lain down through exhaustion and had to be kicked on after it had been relieved of a part of its burden.

The kayak (qajaq), which in certain other Eskimo areas plays such a fundamental part, is of comparatively slight importance here. so slight, indeed, that it has quite disappeared from among the Aivilingmiut and, with the exception of one, the Iglulingmiut too. Only at Ponds Inlet does it seem to be holding its own; in the summer of 1923 there were six kayaks there, and of these one was newly built whilst a seventh was in course of construction. The cause of Image missingFig. 52.Kayaks. the relatively small use of the kayak in this area is partly to be found in the comparatively short period during which the sea is not covered with ice and partly in the introduction of the whaleboat and, finally, in the fact that caribou hunting from the kayak has been entirely displaced by hunting with the gun.

But if the kayak has disappeared from the southern part of the area, it has been there so recently that most middle-aged men have seen it and most of the older men have used it.

In former days the Iglulik Eskimos seem to have had two different kayaks, each for its own purpose: one for caribou hunting on lakes and rivers and one for hunting aquatie mammals; they varied somewhat in form and there were strict taboo rules against using them for anything else than what they were intended for. Of these, the kayak for caribou hunting seems to have disappeared entirely; there are, however, old men still alive who have used it. The present kayak is only used on the sea.

Fig. 52 a is a kayak from Ponds Inlet with its paddle and kayak-stand. The length is 5.85 metres, the breadth 62 cm, height from bottom to upper edge of the coaming 36 cm; the manhole is straight at the back, rounded at the front, 47 cm wide, 52 cm long, the frame 7 cm high. There are three deck-straps: in front and behind the manhole and far to the fore end; the latter is held by two bone eyes whilst the other two are sewn on. Just to the right of the coaming is a rest for the harpoon, saddle-shaped, 8 cm long, of antler with a wooden peg in the end. The kayak-stand is made of a bent wooden band and two cross-stays, the long one 57 cm long and 6 cm wide; the band is 38 and 34½ cm in diameter, 3½ cm wide; in the right end of the short cross-stay is a bone peg, 7 cm long, set in obliquely, which also forms a rest for the harpoon. The paddle is 2.93 m long; of this each of the blades accounts for 1.07 m; 92 cm from the ends is a small piece of seal-thong which acts as a drip-ring. At the middle the width of the paddle is 4 cm, that of the blades 10 cm; the thickness at the middle is 2½ cm.

From Aivilik and Wager Bay we have three broken pieces of paddles which have been edged with bone, held to the wood by long bone pegs; the breadth of this edging is about 1 cm. Fig. 53 (Ponds Inlet) is a rest for the kayak harpoon; it is of antler, 8.0 cm long; on the underside grooves for the lasing lead from the holes to the ends.

The skeleton of a kayak at Ponds Inlet was built in the following manner: Fig. 54 shows the skeleton of the deck: the two gunwales, the fore-and-aft beam and the twenty deckbeams which are lashed on to the gunwales; the fore-and-aft beam is slightly morticed into the five foremost deck-beams but elsewhere lies above them; it is also morticed into the stout, curved deck-beam in front of the manhole. The bottom is formed of a keel which runs from stem to stern, two streaks on each side of it, the two outermost running from the stern to the third deck-beam, the two innermost between deck-beams 4 and 5 from the stern to the sixth from the stem; the distance between the outer edges of the outermost streaks at the middle of the kayak is 47 cm. Furthermore, there are 27 ribs. curved, thin pieces of wood which run from gunwale to gunwale, lashed to the streaks; the height from deck-beam to the upper edge of the keel is, at the middle, 30 cm. Between each rib the streaks in the bottom are lashed together with seal-thong. The construction of the stern (a) and stem (b) will be seen from the sketch fig. 55. The coaming of the manhole is not made fast to the rest of the skeleton; it is 52 cm wide, 45 cm long, 13 cm high; at the after end the deck is flat, at the fore end the nose turns up about 10 cm. The length is 6.01 m.

The Eskimos have names for all the various parts of the skeleton: the manhole: pâq; deck-beams: ajân; keel: niutsaq; gunwale: apúmaq; streaks: siánit; ribs: tikpît; heavy deck-beam in front of manhole: masik; deck-beam behind manhole: iksivautaq; stem: usuijaq; stern: aquaq; kayakstand: asaluk; harpoon-rest: akserkikut; deck-strap: tarqaq; paddle: pautik; paddle-blade: mulingit; drip-ring: naktibik.

I observed that a Ponds Inlet kayak was built in the following manner: the gunwales and stem and stern were made first; then the two deck-beams on each side of the manhole were set in, and, after these, the other deck-beams; then came the ribs, the keel and the other streaks; finally the coaming of the manhole and the skin. covering, which was made of six unhaired sealskins.

This kayak is, as will be seen, very crude and clumsy and will not easily capsize; as the Iglulik Eskimos have no special kayak-jacket which can be fastened round the manhole coaming, it cannot, however, stand much of a sea.

Regarding the kayak at Iglulik we have in Fig. 52 b a sea-kayak made for us by the Iglulingmio Aua at Qajûvfik. It is 5.60 m long, 59 cm broad; stem and stern are pointed and very little upturned. The hole is oval, 50 × 43 cm. the greatest breadth being closest to the after end. Before the hole we have a curved deck-beam of antler, like the other deck-beams mortised into the gunwales and secured by lashing; the ribs are mortised into the lower edge of the gunwales, and lashed to the keel and one streak at each side of the keel. The kayak is during the transportation flattened. Besides we have the descriptions and illustrations of Parry[24] and Lyon.[25] The length seems to have been about 25 feet, but of this five feet were taken up by the long, upturned stem and stern, which resemble those still used by the Caribou Eskimos. The breadth was 19 inches, the depth 10 inches; the manhole was round. The weight was 50 to 60 lbs. It does not clearly appear whether the kayaks which Parry and Lyon describe were for caribou or aquatic mammal hunting. On the plate Parry p. 508 one sees caribou hunting from kayaks with pointed stems of this kind; but a similarly pointed stem is shown on the kayak on p. 274 and which seems to be for aquatic mammal hunting, as the man is carrying it down to the beach. It would thus seem that the Iglulingmiut in former times have used a type of kayak which differed considerably from the Ponds Inlet kayak, unless Parry has not been aware of the difference and in both cases has drawn a caribou-hunting kayak.

I have not seen the only kayak now left in the Iglulik area; but the Eskimos told me that it does not in any way differ from the Ponds Inlet kayak, so much the more as its owner has lived a long time in northern Baffin Land.

As regards the Aiviliks, an old man at Repulse Bay described how their kayaks were built; he could not remember whether there was a difference of design between the sea and the lake kayak. The skeleton only differed from the Ponds Inlet type described above in that the deck-beams were morticed into the gunwales and also lashed, and the ribs were also most frequently morticed into the gunwales. The keel was laid on the outside of the ribs, and these were bound

Fig. 56.Stitches in kayak-skin.

together by a cross-lashing (Fig. 56 a). The manhole coaming was oftenest oval in shape, but sometimes the same as that on the Ponds Inlet kayak. The covering skin was made of six or seven sealskins sewn together; they were first scraped clean of fat with the ulo, then folded and laid in the sun, after which the hair was removed with the salikut scraper. The stitching was done with a double seam, amerng: the two edges were first laid together and sewn with overcasting; then one skin was turned over the other and overcast again (Fig. 56 b). When the skin was to be drawn over the skeleton it was wetted and laid out, the kayak was placed upon it in the middle and the skin was pulled up and around it, the two edges meeting down the centre-line of the kayak; at first it would not meet, but the stitches then put in were made in the fashion seen in Fig. 56 c and the thread was gradually pulled tighter until the two edges came together; this zig-zag sewing was called sukuteruta; the stitches were only to go halfway through the skin. If sufficient wood was not available for ribs. bone or baleen could also be used.

Fig. 56.Stitches in kayak-skin.

together by a cross-lashing (Fig. 56 a). The manhole coaming was oftenest oval in shape, but sometimes the same as that on the Ponds Inlet kayak. The covering skin was made of six or seven sealskins sewn together; they were first scraped clean of fat with the ulo, then folded and laid in the sun, after which the hair was removed with the salikut scraper. The stitching was done with a double seam, amerng: the two edges were first laid together and sewn with overcasting; then one skin was turned over the other and overcast again (Fig. 56 b). When the skin was to be drawn over the skeleton it was wetted and laid out, the kayak was placed upon it in the middle and the skin was pulled up and around it, the two edges meeting down the centre-line of the kayak; at first it would not meet, but the stitches then put in were made in the fashion seen in Fig. 56 c and the thread was gradually pulled tighter until the two edges came together; this zig-zag sewing was called sukuteruta; the stitches were only to go halfway through the skin. If sufficient wood was not available for ribs. bone or baleen could also be used.

Boas[26] figures models of the two kayak types of the Aiviliks. The sea kayak, fig. 106 a, rather resembles the Ponds Inlet kayak but has a round manhole; the lake kayak, fig. 106 b, with its rounded bottom and pointed, slightly bent-up stem, resembles the kayaks illustrated by Parry. In the same work Boas shows paddles for the two types; the sea paddle, fig. 107 b, has a long, pointed blade, the lake paddle a shorter blade, broad and rounded at the ends.

Hall[27] says that the kayak of the Aiviliks is much lighter and smaller than that of the Greenlanders; a kayak, he says, only weighs 25 lbs; presumably he is here referring to the caribou-hunting kayak, but even in that case the figure sounds rather improbable. Rae[28] gives the following dimensions of a kayak at Repulse Bay: length 21 feet, breadth at the middle 19 inches, depth 9½ inches.

Whale boats and other European wooden boats have now partly superseded the kayak and the Aiviliks especially, since the time of the whalers, are excellent seamen and handle a boat with great skill. But it is only the more well-to-do among them who have a whale boat. Of the 27 families who lived on Southampton Island in the winter of 1921–22, five had whale boats; one of these boat owners also had a motor boat. Of the 14 families who lived about Repulse Bay, five of them had boats. The Iglulingmiut had no whale boats, but seven of them had boats with wooden skeletons, covered with skin. The skeleton is a copy of that of the whale boat or perhaps it is in fact that of a whale boat. When the Eskimos tell that in former days the people at Iglulik and Admiralty Inlet had large skin boats they are probably referring to such boats as these, originating out of European technique. The important Eskimo women's boat, the umiak, does not seem to have ever been. known to the Iglulik Eskimos, and none of the earlier expeditions have seen these boats among them.

Fig. 57 is one of these Eskimo skin boats. from the Iglulingmiut at Itibdjeriang. It is 4.80 m long, 1,45 m broad at the middle. It is very flatbottomed. The frame, which is made of European planks (presumably from an older boat), a few barrel staves and pieces of antler, consists of: a keel, constructed of a half-round beam over which a four-sided beam is laid the greater part of its length, at one end prolonged by a sledge cross-slat. From this, on about the same plane, run 15 pairs of crossbeams which are again prolonged in the ribs, which are attached to the gunwales, each of which consists of several pieces. Under the cross-beams and ribs are a number of stringers which, however, are not continuous but are made up of small boards. The stem is formed of a bent piece of antler and the stern is supported by two sloping beams and a vertical piece of antler. In the stern of the boat are two thwarts and in the bows three pairs of oblique stays from keel to gunwale; the middle pair support a thwart. At each side there is a rowlock, consisting of a vertical pin jutting above the gunwhale and covered with skin. At the stern a long antler, the lower end of which is fastened to the thwart, forms a fork for the steering oar; the fork itself is covered with walrus skin lashed on with sinew-cord. On the whole the various parts of the frame are held together by seal-thong lashings, although a number of nails have been used and on one gunwale there is a large piece of iron mounting fastened on with screws. Covered with three unhaired, bearded-seal skins, the seams being tightened with blubber.

In former days two kayaks tied together were used as ferries over open water. At Repulse Bay I saw a man row ashore from an island on five inflated harpoon bladders fastened together, with a board laid across the top.

As a consequence of the roving life they lead, the Eskimos have a surprising knowledge of their land. When caribou hunting especially, they travel far and wide and on such occasions they take notice of all the details of the otherwise so monotonous landscape. This is necessary, if they are to be able to find the caches of meat and skin later in the winter, and they are able to explain to other Eskimos where these places are, so that the latter can find them with certainty, even if they have never been at the place previously. If a man is about to travel on a course which he has never followed before, it is described to him by another and in most cases he can then find his way along it. Much frequented routes through undiversified country are often marked by cairns — usually merely a stone set on end at prominent points; this is true, for instance, of the land passage from Cape Wilson to Usugarssuk on the main road from Iglulik to Repulse Bay. It is rarely that an Eskimo on a journey goes astray; of course it does happen that when it is snowing, or a blizzard is blowing, or in the dark, he cannot find his bearings; but when conditions improve he can almost always find his way again.

Most of the Iglulik Eskimos know two of the three principal areas of which their country is made up (Southampton Island, being a recent acquisition, is not included), and many of them know all three. On page 22 statistics have already been given of the topographical knowledge of the Tununermiut. As a rule it is the most skilful hunters and travellers who know most of the country. At  Fig. 58.Eskimo map, from Lyon Inlet to Ponds Inlet: drawn by Ivaluartjuk.

Ponds Inlet I met a man who knew the whole of the country between Chesterfield Inlet and Ponds Inlet and had also travelled to Piling, North Devon, Cornwallis Island, North Somerset and Prince of Wales Island; on the other hand I met a man at the same place who had spent the whole of his life in the Ponds Inlet district, where the limits of his knowledge were Milne Inlet and Anaularealing.

Fig. 58.Eskimo map, from Lyon Inlet to Ponds Inlet: drawn by Ivaluartjuk.

Ponds Inlet I met a man who knew the whole of the country between Chesterfield Inlet and Ponds Inlet and had also travelled to Piling, North Devon, Cornwallis Island, North Somerset and Prince of Wales Island; on the other hand I met a man at the same place who had spent the whole of his life in the Ponds Inlet district, where the limits of his knowledge were Milne Inlet and Anaularealing.

The Eskimos, at any rate the more intelligent among them, become familiar with a map in a surprisingly short time, even if they have never seen one before. They are also able to draw a map of the areas with which they are familiar. Such Eskimo maps can give much information regarding otherwise unknown areas, if only one is aware of their limitations. Fig. 58 is a map of the area between Repulse Bay and Ponds Inlet, drawn by Ivaluartjuk, a man about 60 years old. The two most conspicuous defects of Eskimo maps will be observed at once: distances and directions cannot be relied upon. A stretch of country that has been of importance to the drawer, one that he knows well and where he has lived for a long time, is involuntarily drawn bigger and with more detail than areas which he only knows from fleeting visits. On this map it will be seen that the southern part where the man now lives, is drawn with quite a different extent and accuracy than more distant regions, for instance in northern Baffin Land. But in places he knows well all the details, points, bays, islands or lakes are indicated and everything has a name. How good an Eskimo map is depends to a great degree upon the knowledge and intelligence of the drawer. At Ponds Inlet an Eskimo drew a detailed, fairly accurate map of the coast-line from Ponds Inlet to River Clyde, whereas another man of the same coast only made a line which turned when it reached the edge of the paper and which was given a number of small indentations to mark the fjords.

A number of other Eskimo maps, drawn by Iglulik Eskimos, are published by Parry,[29] Hall[30] and Speck.[31]

The names play an important part in the Eskimos' knowledge of the country. Their lack of variety and continual repetitions often make them of little use on European maps. In addition, names of large geographical units are usually lacking — Melville Peninsula, Fox Basin, Baffin Land, Bylot Island. The Eskimo names are oftenest connected with some particular locality or other, frequently a settlement or important hunting ground; these names, however, sometimes spread and are used in respect of large areas. The name Aivilik is connected with the point on the north coast of Repulse Bay, where the most important summer settlement of the Eskimos once was; but it is also used of the whole of Repulse Bay. Maluksitak is the name of a point at the northern entrance to Lyon Inlet, but it is used of the whole of Lyon Inlet; Tununeq, which is now used for the whole of Ponds Inlet area, was originally a cliff in Milne Inlet; Uvkusikssalik was originally the name of a soapstone quarry in Wager Bay but is now used for the whole of the bay.

Lines of communications among the Iglulik Eskimos follow definite routes, chosen because terrain and hunting chances are best along them. Several routes of this kind are described by Boas.[32]

From Repulse Bay to Chesterfield Inlet runs a sledge-route that is now used every year by the mail sledges, but which was of importance earlier as a trading route. From Beach Point it follows the coast southwards to Wager Bay; in order to cross this bay, the greater part of which is open in winter, the traveller must proceed along the north shore until the narrowest place has been passed, then to the south-east across a number of valleys and lakes till the coast is reached south of Nuvuk; from there along the coast to Fullerton, across the bay to Depot Island and on along the coast to the mouth of Chesterfield Inlet. From Repulse Bay to Iglulik the route usually followed is: eastwards to Haviland Bay, along the river Kûgârssuk. over several lakes to the head of Gore Bay, over a narrow isthmus to the mountain Kingâbik in Lyon Inlet, near its mouth, along the coast northwards to Pitorqaq at Cape Wilson (but travelling overland past Pt. Elizabeth). From there overland via a rather winding course to Usugarssuk, on to Ipiutaq, the isthmus of Amitsoq peninsula, Ingnertoq, over Halls Lake to Pingerqalik and Iglulik. Another route, which was used by Hall in 1866 and 1868, runs from Haviland Bay over several lakes to Ross Bay in Lyon Inlet, proceeding overland past the mountain Pinguarssuk to Usugarssuk river, which is followed as far as the coast. From Repulse Bay another important route runs over the lakes of Rae Isthmus to Committee Bay.

The most common routes from Iglulik to northern Baffin Land are: Through Gifford Fjord over Asta's Lake to Saputit, the head of Admiralty Inlet; from Nyeboe's Fjord over the lakes Ivisarortoq and Saputit to the head of Admiralty Inlet; this latter route, which Lavoie[33] travelled in 1910–11, starts, he says, from Whyte Inlet, a consequence of the mistake he made in believing that it was Autridge Bay and not Aggo Bay he came to.

To Ponds Inlet the route is: Through Murray Maxwell Bay, over the lake Angmalortoq to the head of Steensby's Fjord, from there over Taserssuaq and along the river Phillips Creek to the head of Milne Inlet. Another route runs from Isortoq, the fjord east of Steensby Fjord, to the fjord Anaularealing over a number of valleys and lakes. From Ponds Inlet the sledge route leads along the coast southeast to River Clyde and Home Bay. From Admiralty Inlet communication with Ponds Inlet proceeds round C. Charles York; the passage from the head of Adams Sound to Navy Board Inlet can only be made on foot.

Whaling, and later on the trading stations, have each contributed towards erasing the old tribal boundaries, and the mutual intercourse and trade between the tribes has undergone a very radical change. At the trading stations the members of the different tribes meet and, although they do not as yet regard each other as kinsmen, the former attitude, frequently one of hostility, as no longer observable.

At Chesterfield Inlet the Aiviliks met Qaernermiut ("Kinipetu"). Tradition says that in earlier times there has been trade between them at Baker Lake, the Aiviliks buying wood in exchange for dogs. The relations between the two tribes seem to have been good as a rule. Klutschak[34] mentions an instance of a quarrel: Two Kinepetus were living among the Aiviliks; when shooting at targets one of them was wounded. The tribes then agreed to choose three men each, and these were to represent the whole tribe in the quarrel; they could not cross the boundary of the other tribe without risking death.

The relations between the Netsiliks and the Aiviliks seem to have been much more antagonistic. Rae[35] writes: "The natives of this part of the coast (Pelly Bay) bear a very bad character, and are much feared by their countrymen of Repulse Bay". Hall[36] writes: ". . . there existed a strong war-like feeling between the natives of that region (Netsilik) and those of Iwilik", and Klutschak[37] "Seit langer Zeit schon standen die Netchilliks und Eivillik-Eskimos in einer Fehde, deren Ursprung in längst vergangenen Generationen zu suchen ist und nur durch die unter den Eskimos allgemeine noch existierende Blutrache fortgepflanzt wird", and later[38] he says that an Aivilik Eskimo undertook a journey of 400 miles in order to take blood-vengeance of a Netsilik who had killed his uncle.

In the whaling season, when Netsiliks and Aiviliks came together. there were often hard fights with the fists; on Southampton Island there still lives an Aivilik Eskimo who once killed a Netsilik in a fist-fight.

This state of war has now more or less given place to mutual contempt; the Aiviliks look down upon the Netsiliks, ridicule them for their swinish habits (they sometimes use their drinking cup as a night-pot, they aver) and their lice and look down upon them with about the same feeling as the metropolitan looks down upon the rustic. Nowadays, however, many Netsiliks live at Repulse Bay. Wager Inlet, Depot Island, attracted by the trading stations; as a rule they live by themselves, but the marked difference is becoming more and more blurred and there are now several cases of intermarriage between the two tribes. The Aiviliks now often buy lamps and musk-ox dippers of the Netsiliks in exchange for European trade goods.

With the Sadlermiut, the inhabitants of Southampton Island, the Aiviliks were also on a strained footing; on the whole this peculiar tribe avoided connection with other Eskimos. Lyon[39] writes of them: "They (the Aiviliks) hold these near, but unknown neighbours, in the most sovereign contempt, considering them as savages and as vastly inferior to themselves."

According to Boas[40] there was in former times a connection between Iglulik and Cumberland Gulf via the Pilingmiut, a group of Eskimos on the west coast of Baffin Land; of this connection I could not even find any remaining tradition.

Between the Tununermiut and the Akudnermiut on the east coast of Baffin Land there has formerly been considerable intercourse; Boas[41] refers to it as being "not very frequent". Whaling and trading have, however, attracted a number of Akudnermiut to Ponds Inlet, just as a number of Ponds Inlet Eskimos have been led to the newly established trading station at River Clyde; there has also been some intermarrying.

Stefansson[42] heard among the Copper Eskimos the name "Turnunirohirmiut"; but I doubt that there has been a regular trading route between the two peoples, as he believes. At any rate at Ponds Inlet I did not meet any Eskimo who had been in touch with either the Netsiliks on Boothia or the Eqaluktoqmiut at Albert Edward Bay on Victoria Land.

Boas[43] says that the Aggomiut, as the inhabitants of northern Baffin Land are called in Cumberland Gulf, have intercourse with the inhabitants of Ellesmere Land via North Devon. Presumably it has been roaming groups of Polar Eskimos (which here are called Akukitoqmiut) whom they met there. That Eskimos from Admiralty Inlet have visited the Cape York district and in many respects have influenced the people there and, among other things, taught them the use of the kayak, bow and salmon spear, is well known.[44]

- ↑ Cf. Boas 1901 p. 90.

- ↑ See Boas 1907 fig. 220.

- ↑ 1824 p. 324.

- ↑ 1824 p. 514.

- ↑ 1879 p. 221.

- ↑ Parry 1824 p. 515, Lyon 1824 p. 324, Hall 1879 p. 307, Boas 1901 p. 90.

- ↑ 1824. p. 324.

- ↑ 1824 p. 201.

- ↑ 1824 p. 333.

- ↑ 1824 p. 520.

- ↑ l. c. p. 358.

- ↑ 1879 p. 240.

- ↑ Cf. Lyon 1824 p. 159.

- ↑ 1824 p. 521.

- ↑ 1824 p. 533.

- ↑ 1824 p. 518.

- ↑ p. 54.

- ↑ 1824 p. 437.

- ↑ Cf. Parry 1824 p. 519.

- ↑ 1824 p. 111.

- ↑ 1824 p. 519.

- ↑ 1879 p. 67.

- ↑ l. c. p. 69.

- ↑ 1824 p. 506, illus. p. 274 and 508.

- ↑ 1824 p. 321.

- ↑ 1901 p. 76.

- ↑ 1879 p. 216.

- ↑ 1850 p. 94.

- ↑ 1824, p. 197, 198 and 252.

- ↑ Hall 1879.

- ↑ Speck Pl. VI.

- ↑ 1888, p. 450.

- ↑ See Bernier 1912.

- ↑ p. 227.

- ↑ 1850 p. 121.

- ↑ 1879, p. 82.

- ↑ p. 150.

- ↑ p. 228.

- ↑ 1824, p. 345.

- ↑ 1888, p. 432.

- ↑ l. c., p. 464.

- ↑ Prehistoric Commerce p. 7.

- ↑ l. c., p. 443.

- ↑ Knud Rasmussen 1905, p. 26. Steensby 1910, p. 261.