Material Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 10

Like the other Eskimo tribes, the Iglulik Eskimos form no political or social unity. They are only a group of families, related by the same manner of living, the same forms of implements and clothing, the same methods and customs, to some extent connected by blood ties. There is no superior authority, but custom and habit and tradition provide certain rules which must be observed. In particular it is the numerous taboo regulations which have a profound effect upon their manner of living, some of them being general, having become established upon tradition from generation to generation, others imposed temporarily by a shaman for a particular occasion, to heal a sick person, to ensure good hunting, and so on. If these regulations are broken, the person concerned is regarded as one who, by his behaviour, has been the cause of new misfortunes; but he is not punished in any other manner. There is no executive authority, but on the other hand there is a sort of judicial authority: the shaman.

Within each settlement, which as a rule comprises a few families, often connected by kinship, there is as a rule an older man who enjoys the respect of the others and who decides when a move is to be made to another hunting centre, when a hunt is to be started, how the spoils are to be divided, when the dogs are to be fed, etc. He is called isumaitoq, “he who thinks". It is not always the oldest man, but as a rule an elderly man who is a clever hunter or, as head of a large family, exercises great authority. He cannot be called a chief; there is no obligation to follow his counsel; but they do so in most cases, partly because they rely upon his experience, partly because it pays to be on good terms with this man. At Itibdjeriang, Ingnertoq and Iglulik older men were isumaitoqa; on Southampton Island Audlanâq, who was only 35 years old, had attained that dignity by his skill.

In the family circle the husband is usually the one to decide: there are, however, examples to the contrary.

The distribution of labour between man and woman — for there is no other distribution of labour — is at once apparent: the man goes hunting, procures food and skins for the house and he is also the artisan who builds the house, makes the sledge, fashions his and his wife's implements, scrapes skins. The wife sews clothing, prepares the skin (except the scraping, with which the husband helps). attends to the lamp, cooks meat and looks after the children. But it is no rare occurrence for women to participate in the hunt, especially salmon fishing, where, however, net fishing is always the task of the men, the women fishing with the hook. At Ponds Inlet I heard of several women who were skilful seal-hunters, both ũtoq and maupoq hunting. The women are often clever at fox-trapping, too; a woman at Ponds Inlet had caught 15 foxes in one winter. Two older. rather lazy men at Ponds Inlet had each two clever wives who also did most of the hunting and were very skilful at catching seals, narwhals and foxes. Most of the women, however, spend nearly all their time indoors, sitting on the platform with their sewing and all day long singing their interminable monotone song with the eternal refrain: aja-aja-aja-a.

Marriage. Children are betrothed at birth; as soon as a man receives a son he buys a wife for him for some utensil or other; the aim is to secure domestic help in good time. But if his fiancée should die in the meantime the young man is often placed in an unfortunate position, very often having to wait for a death or some other opportunity of acquiring a wife, and he frequently has to be content with an old widow. Brothers and sisters may marry, and a man may marry two sisters (this is denied by Lyon 1824, p. 353); the case I quote was a man at Ponds Inlet.

Marriage takes place at an early age. The man, as soon as he is able to feed himself and his wife, the woman as soon as she is able to sew and tend the lamp, even if she is barely mature. One sees married women who are scarcely more than fifteen or sixteen, a fact that is also mentioned by Parry[1] and Lyon.[2] Marriage is entered upon without any ceremony; the young man simply comes and fetches his future wife and takes her to his house.[3]

Some men, usually clever hunters, have two wives; in earlier times it is said that there were some who had three. In all there are now six men who have two wives, but formerly this seems to have been a more common state; thus Parry[4] says that among the Iglulingmiut twelve had two wives, and some of the younger men were betrothed to two; he also says that as a rule there was a difference of five or six years between the ages of the two wives, but this does not seem to be the case now. And of the Aiviliks Gilder says: "At least half of their married men had two wives." As a general rule the two wives seem to get on well together; the wife who basks under the husband's favour at the moment is the domestic head of the house. But that matters have not always been so idyllic appears from Lyon's description of how a man had to stop a fight between his two wives by stabbing them in the head with a knife. A man at Iglulik told me that he had a wife there and one at Ponds Inlet; but as they did not agree very well, he stayed with each one in turn. On the other hand it happens sometimes that one woman has two husbands; but usually only for a short period, as the two husbands do not seem to agree so well as two wives.

The marriage state is not very stable. Exchanging wives and divorce followed by a new marriage, are common and are looked upon as natural occurrences; when a couple separate the children belong to the mother, and therefore marriages in which there are children. especially sons, are more stable than childless marriages. But even then marriage may be too much for these people; with smiles and much head-shaking they told me, for example, of a young man who was now about to exchange his fourth wife. Two young men at Iglulik were nuliaqatên, exchanged wives at certain intervals, mostly for a year at a time; one of them, however, had the say in these matters and fixed the period of exchange; if they neglected to make the exchange, one of them would have bad hunting. The women submit to this changing with astonishing resignation; they seem to be satisfied if only they have someone to provide for them. Marriages are often marriages of convenience; only rarely does one see man and wife caress each other: but on the other hand beatings and harsh words are not common. As a rule the wife must put up with anything from her husband, although now and then an especially clever wife may be the "master of the house". The relations between man and wife seem mostly to be good — they are comrades. In sexual matters, however, they are rather loose and the women often hardly know who is the father of their children. One man had been away two years on a mail journey to Fort Churchill; on the day after his return his wife gave birth to a daughter; he was delighted at the surprise.

A peculiar sexual excess is that the men sometimes copulate with animals which they have just killed; we also heard tell that women occasionally had sexual relations with dogs.

Childbirth must not take place in the snow house or tent in which the family resides, but in a separate little snow house or tent built by the side of the other and where the woman must spend the first two months after confinement; she may receive visitors, however, but has her own lamp and cooking pot and cooks her own food. The birth itself is usually easy and she helps herself; the navel-string is cut with a piece of flint, a strip of skin is tied round it and the after-birth is kept and buried together with the piece of flint. A woman who gave birth to a child in August, 1922, on Danish Island, dug a hole in the gravel in the tent floor, placed a box on two sides of the hole, sat over it with her elbows supported on the boxes and thus brought her child to the world. Before the afterbirth had come, her eldest daughter came running into the tent and began to talk; "that is why the child. which otherwise would have been a boy, became a girl, as he drew the genitals inside him". A woman on Southampton Island who, in the summer of 1922, bore her fourth child, had no skin for a separate tent but spent the time after confinement in the big tent; when the period was over, the tent was moved to another site a few metres from the old one; the old clothing was thrown away.

Immediately after birth the child is given a name, and is usually called after the last relative to die, most frequently of the mother's family, regardless of whether the person was a man or a woman. By this means the old names of the tribe are preserved, and many of the names we find in Parry and Lyon are still to be met with. If no relative has died recently, the husband names the child.

This naming often gives rise to peculiar names, as is eloquently shown by the list given in a previous chapter of the names of all the adult Igluliks and their meaning.

Infanticide does not occur among the Iglulik Eskimos; the custom of abandoning newly born female children which is so widespread among the more westerly Central Eskimos does not seem to have ever been practised here. This may be due to the fact that conditions of life here are rather better, that it is somewhat easier to procure food for these people, to whom the aquatic mammals are of more importance than to the Netsilik, Copper and Caribou Eskimos.

Adoption of children is, on the other hand, very common. A very large number of the children are adoptives (tiguagkat); of the eighteen children at Repulse Bay in the winter of 1921–22, eight were adopted. These are not alone children who have lost their parents and have been adopted by other families, nor are they always children of very large families (for instance twins) or whose parents are poor hunters who have difficulty in procuring food for them. It is often simply a business transaction, the adoptive parents paying for the child; these offers are sometimes so tempting that the parents cannot resist them. For instance, a young married couple at Iglulik, who already had a boy of four or five, sold a son of nine months to a rather elderly man at Ponds Inlet who already had two children, the price being a rifle for the father and an accordion for the mother. A young woman at Ponds Inlet sold her newly born son for a large soapstone lamp. One of the cleverest hunters on Southampton Island had only one of his own children; he had given a son to an old, childless couple at Repulse Bay, another to a man on Southampton Island who already had two himself and one adopted child. In many cases it seems to have been done merely for the sake of friendship or kinship; often the payment is not at all in reasonable proportion to the "value" of the child. At times it is almost a matter of charity, as in the winter of 1924 when a couple who were blind were given an infant child. Parry,[5] too, mentions the general spread of this custom and says that it is nearly always sons who are given away. This, however, does not apply now; although the new parents would rather have a boy, the actual parents prefer to keep them. Adoptive children are treated exactly as the family's own children.

For the children themselves this adoption is mostly a bad exchange; as a rule they cannot, of course, get milk and therefore they have to be brought up on soup or chewed meat, which they suck from the mother's mouth, and of course a large number of them die of it. An adoptive child, eleven days old, at Pingerqalik was fed on caribou fat and blubber; twice a day two other women in the house, who were nursing, pressed a little milk out into the lid of a gut-skin box and this was poured into the child; at twelve days old it already began to get cooked meat. Adoption undoubtedly is very greatly to blame for the terribly high infant mortality.

The child spends the first part of its life in its mother's back-pouch, where at first it lies in the bottom, stark naked; by means of the wide shoulders of the frock it can be put to the breast without being taken out into the air, as Lyon also mentions.[6] As soon as it grows a little and receives its first garment, it is allowed to put its head out of the pouch. When it can sit up, it is often taken out of the pouch and sat on the platform in its combination suit. The mother has an astonishing faculty for knowing when the child wishes to relieve itself, and takes it out of the pouch and holds it the while. Big children, up to three or four years, are also carried in the back pouch on journeys.

It is surprising what infants are exposed to as regards cold. In a snowstorm and severe frost the head is often protruding out of the pouch, with the result that the mother is unable to turn her hood up. In −20° I have seen a woman bring her nine-months adoptive daughter out of the pouch and sit her on the sledge for a little while with her lower body bare.

During the first two years the child is normally fed on the breast, and in fact even up to three or four years one occasionally sees them given the breast, as Lyon[7] also draws attention to. On the other hand, infants are often given a drop of soup or a piece of meat or fat to suck.

As a rule, children are allowed their own way, even when quite small; if a little mite wants a sharp knife or ulo to play with, he gets it; I have seen a boy of just over twelve months fall down from the platform to the floor of the snow house, stark naked and with a sharp flensing knife in his hand; it is seldom that they cut themselves, however and the Eskimos say that it is good for them to learn early to handle edged things.

The following incident from Southampton Island is typical of child rearing: Agorajâq was a boy of three of four years, and was in the house of his grandfather Angutimarik; he was a determined and ill-natured little chap, knew what he wanted and as a rule had his own way. He came into the house after having been out playing in the snow, and his inner frock was filled with snow, for which reason Angutimarik beat it. This made him furious. he howled and struck at his grandfather, who calmly continued until he had finished. Then the boy's anger turned upon Makik's four year old daughter, to whom he was often cruel; he tried to strike her face. but she pushed him over. He screamed terribly and his grandfather lifted him up; again he rushed at her, was again pushed over and again picked up; this was repeated three times. Finally, Angutimarik took him aside and asked him if he would like a piece of meat. "No!" "Soup?" "No!" Then he went outside. Shortly afterwards his grandmother called to him: "Will you not have a little cooked meat". "No". "Nor soup?". "No, I won't". Then he came in through the door and struck at his grandfather with his toy whip. "Come now and have some meat and soup while it is warm", said Angutimarik. "No!", and out he went again. A short time afterwards he appeared again in the doorway with the whip. "Do you want some soup now?" asked his grandmother. "No!" "Are you sure you won't have a little soup?". He came closer and was given a big cup of soup. "Would you like some meat too?". He started to eat ravenously.

Once, however, I saw his grandparents thrash him; still, he was more ill-natured than children usually are; most of them are good humoured and it does not spoil them much to get their own way.

I have only seen one example of children being severely brought up; this was a woman on Southampton Island, who often thrashed

Image missingFig. 163.

Toy harpoon.

her two adoptive children, especially one, a dear little girl, who was often unnecessarily beaten and gave the impression of being rather cowed. The other Eskimos also said that the woman was too severe and, when her right arm became swollen with rheumatism or something like it, the shaman said that it was because she beat the little girl so much.

The children play like other children, imitating the doings of their elders. The boys are given miniature sledges, whips and hunting implements such as harpoons, leisters, bows, arrows and slings. Often a pup is made to act as sledge dog and its treatment is by no means gentle. The claws and sinews of the flippers of a bearded seal are made to represent four dogs with traces; they make toy houses and tent rings in the gravel outside. The girls have a small lamp and cooking pot, and they play at dolls.[8] Of other toys there are tops and bull-roarers. Half-grown girls squat down opposite each other and hop in concert, singing long, monotone songs the while; this game is called ajangartut. During the shaman séances on Southampton Island the children played "head lifting". They are very hardy and run about and play even in very severe weather.

The following is a description of some of the playthings contained in the collection:

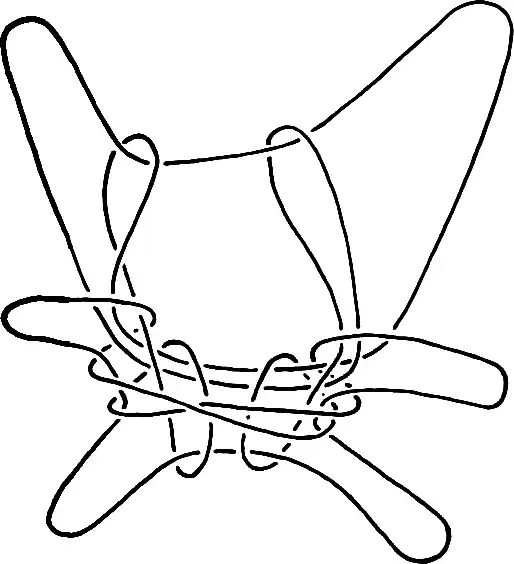

Fig. 163 (Iglulik) is a toy harpoon, consisting of a wooden shaft, to the fore end of which is scarfed a foreshaft of ivory; this foreshaft has a transversal groove and, on each side of this, four dark patches to represent the lashing of the joint. A thong runs from an eye on the rear of the foreshaft in under the lashing of the tikâgut. Under this thong runs a strap on the line, which is of seal thong, ending at the back end in a loop and at the fore end holding the harpoon head, which is of antler with an iron blade, slightly flat with two bifurcated dorsal spurs. Total length 59 cm.

Whereas this harpoon is apparently intended to represent a walrus harpoon, a loose foreshaft (from Iglulik) belongs to a toy kayak harpoon; it is of ivory, has a wide tenon at the butt end, a curved, slender point and two pierced holes at right-angles to each other; 9.0 cm long.

Two harpoon heads of ivory, both from Iglulik, illustrate the two now common types: the seal-harpoon head, flat with two barbs, two dorsal spurs, and the walrus-harpoon head. thin, with the blade at right-angles to the line hole, no barbs; 35 and 2.8 cm long respectively.

From Iglulik there is a bow with four arrows. The bow is made of two pieces of antler nailed together with iron nails; it is 53 cm. long, about 2 cm wide; the string, of twine, is fastened at one end to a knob, at the other end in a hole. The arrows have wooden shafts with nocks (one of them is strengthened here with sinew-thread binding) and iron heads, three of them blunt, the fourth hammered out to an only slightly sharp blade, inserted in the fore end of the shaft which is lapped with sinew-thread: lengths 24 to 32 cm. Another toy. bow from Iglulik is of one piece of antler, 28½ cm long. 1.3 cm wide, string of sinew-thread, held by two knobs at the ends, an arrow with wooden shaft and a blunt iron head, 23 cm long.

A salmon spear from the Aivilingmiut has a thin wooden shaft and a centre prong of iron, side prongs of musk-ox horn and barbs of iron; lashing of sinew-thread; 61 cm long, of which the side prongs measure 11 cm.

A sledge (Iglulik) is of wood. with runners 16½ cm long and 2½ cm wide, upturned at the nose; six cross-slats about 8 cm long; double lashings of sinew-thread. The draught line, of sealskin, is fastened on by knots in holes in the runners and ends in a loop and a bone toggle; it extends 10 cm beyond the nose of the runners. Four trace buckles with traces and harness, 50–74 cm long. A small toy sledge from Ponds Inlet is of wood, 6.0 × 1.8 cm; the nose is slightly upturned: the cross-slats are not indicated, but the runners are cut out on the under side.

Fig. 164 (Aivilingmiut, Southampton Island) is a kayak with a man in it, carved in ivory. The kayak is rather broad with the ends slightly turned up; it has four deck-straps; paddle and harpoon are pushed in under the two foremost straps. The man has a face and arms to the front; the dress is not indicated. 17.5 cm long.

An ulo (Chesterfield Inlet) has a blade of red slate, handle and tang of ivory; the blade is held on by two pins, likewise of ivory; length of blade 3.5 cm; total width 3.3 cm.

Fig. 165b (Ponds Inlet) is a lamp of soapstone of the usual form. 13.8 cm long. A number of other toy lamps have lengths varying from 17.2 to 4.1 cm: four of them have a longitudinal partition which shuts off a small space at the back. I have seen lamps like the biggest of these used as anteroom lamps.

Fig. 165 a (Ponds Inlet) is a soapstone cooking pot, square with sharp corners, where there are holes for suspension cords; Image missingFig. 164.Toy Kayak, carved in ivory. 14.1 cm long, 3.8 cm high. A number of smaller, similarly square cooking pots are from 5.7 to 1.9 cm long.

Two dippers of musk-ox horn from the Aivilingmiut, Southampton Island, are 6.1 and 9.2 cm long. A toy water-scraper from Iglulik is of caribou scapula, 6.8 cm long. A cup, of soapstone (Kingâdjuaq) is 6.4 cm high, with a top diameter of 7.2 cm, and is apparently a copy of a European tea-cup, widest at the top; a similar one from Ponds Inlet is more cylindrical, 4.1 cm high, 3.9 cm wide at the top.

Fig. 166 (Repulse Bay) is a toy blubber-pounder, of musk-ox horn, 6.3 cm long.

An ajagaq (Pingerqalik) is exactly like fig. 170.1 but only 3.5 cm long, with 13 holes; the stick is 3.0 cm long.

A drum without a skin (Itibdjeriang) is a bent, flat piece of wood, 19 cm in diameter, about 1½ cm wide, the ends held by a sinew-thread lashing; the handle is 12 cm long and has a notch in one edge near the fore end, in which the frame lies. A drum-stick, found at Kûk, Southampton Island, is of wood, 20 cm long, round; 10 cm Image missingFig. 165.Toy cooking-pot and lamp. of the length are occupied by the rather thin handle, which ends in a knob; the other part is thicker and lapped with a strip of seal-thong.

Fig. 167 (Ponds Inlet) shows the usual, traditional type of doll, of wood, with no face or arms and no hint of clothing; 11 cm long. Other wooden dolls, however, have the feet or the lower edge of the trouser-legs indicated; some of the figures have faint signs of hanging breasts and are thus females; the others may be presumed to be males. Their size varies from 5 to 17 cm. A number of wooden dolls of the same type have Image missingFig. 166.

Toy blubber-pounder.

Image missingFig. 167.

Wooden doll.

clothes on, of caribou skin of the usual cut of frock and trousers.

A large doll from Pingerqalik (Fig. 168) is made of caribou skin with the hair inside and stuffed with caribou hair; it has head, arms and well-developed legs, a hood of light caribou skin and black edge and hanging fringes, frock with white border at the bottom and a small flap at the back, and trousers; it seems to represent a boy. Length 25 cm, breadth 9 cm. A similar, dressed doll from Ponds Inlet is figured by Speck.[9]

Fig. 169 (Repulse Bay) is a bird figure with flat under-side (tingmiu jaq), of ivory, decorated with rows of dots along the back; 3.6 cm long. Two others from Repulse Bay are of similar size and have respectively one and three rows of dots lengthwise along the back; one from Iglulik is only 1.4 cm long, unornamented. None of these bird figures have a hole in the rear end such as these tingmiujat usually have; Parry,[10] however, figures one which has this hole, and it has a human forebody. Image missingFig. 168.Doll with clothing. The Iglulik Eskimos do not seem to know the use of these figures in games, such as Boas[11] mentions from Cumberland Gulf.

A bull-roarer from Iglulik is of wood, 7.8 cm long, 1.8 cm wide, flat, slightly curved, with deep notches in the edges and, at the narrow end, a hole in which is fastened a piece of sinew-thread, 17 cm long, ending in a noose. A buzz (Beach Point), consists of a small vertebra of a white fish; through the two longitudinal canals are sinew- threads so that it can be made to spin round when they are pulled; 3.7 cm long.

Boas[12] says that the children play at seals with a piece of skin with holes in it.

In the dark winter days and evenings, time often goes very slowly, especially when snowstorms and blizzards put a stop to hunting; the Eskimos eat and sleep, tell stories and talk, and play games; in summer, too, during the light nights when there is no inclination to sleep, games and pastimes continue merrily, often till the sun is again high in the heavens. Mention has already been made of the games and playthings of the children, and now those of the grown ups will be described.

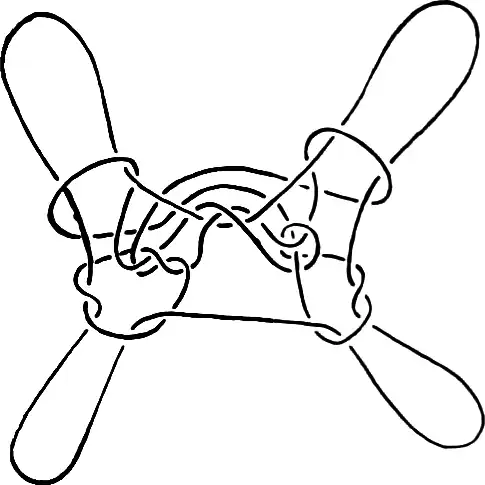

Ajagaq is a game, which consists in catching on a stick a piece of bone with holes in, fastened to the stick by a cord (cup-and-ball); not all the holes have the same value. Fig. 170.1 is a rather imaginative bear figure carved in ivory, with numerous holes on the underside and front; in the back is an eye to which the cord, of sinewthread, is fastened. The stick, of ivory, consists of a fairly wide, flat shaft and a round point; at the junction of these two the cord is tied. Image missingFig. 169.Bird figure. Length 7.7 cm, that of the stick 9.7, of the cord 15 cm. Three other similar ajagait have lengths. from 6.6 to 10.1 cm; one of them has a dot-andcircle ornament on the back. The same form is referred to in Hall.[13]

Fig. 170.2 (Aivilingmiut) is another common form of ajagaq; it consists of a bearded-seal humerus, from which most of the growths have been cut away in one end and an elongated hole has been scraped in the soft face of the cut; a natural eye in the bone forms the second hole. The cord is fastened to an eye on the middle of the bone; there is another eye beside it. Length 14.7 cm. The stick is of ivory, 7.7 cm long and consists of a flat, four-sided handle and a flat point; between the two a cord, 18 cm long, is fastened by means of a groove. Five other ajagait are of the same bone; three of them have only the natural eye; one has other three holes in one end, one in the other, and one has five drilled holes in a row on the underside.

Fig. 170.3 shows a third ajagaq, of ivory, with a hole in the fore end and five on the underside; an eye in the back; 8.4 cm long. The stick has a flat handle, round point and the cord is fastened in a hole; the stick is 9.8 cm, the cord 21 cm long. Seal scapulae, or carvings in the form of fish, etc. are occasionally used too.[14]

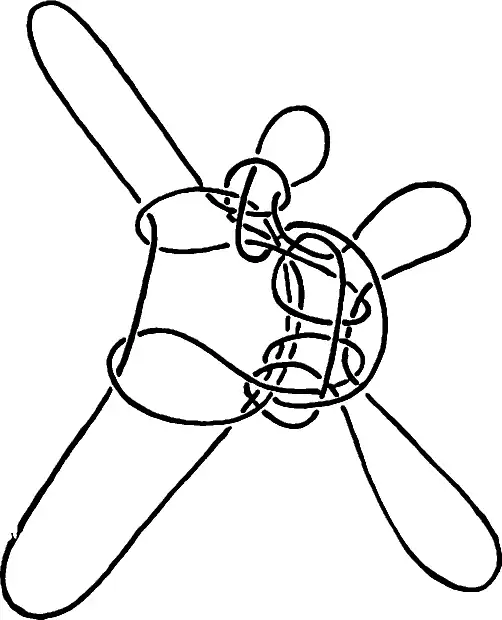

Nuglutang. This game is also known but is not played much now; it is mentioned by Klutschak.[15] It consists of a piece of bone with. holes, hanging down from the roof, the cord being stretched tight by means of a weight. On a sign being given all the players strike at the holes of the bone with a pointed stick, and the one who succeeds in getting his stick into a hole wins.[16]

Fig. 171 (Iglulik) is a nuglutang of ivory, 4.5 cm long, almost round, pierced with large holes in both ends and at the middle with two holes at right-angles to each other. A similar one from Ponds Inlet (new, unused) is similar in shape, 6.5 cm long; the seal-thong is fastened to both ends; the stick is 26 cm long and consists of a point of ivory, 11½ cm long, blunt, scarfed with a nail to a wooden shaft, which is widest at the butt end.

These games have now to a certain extent been superseded by cards; it is always the same fairly simple game that is played; the women especially are devotees and it is nothing uncommon for them to play throughout the night. Stakes are made, often valuable objects such as knives, axes, tobacco, etc., and the gambling passion is often very much in evidence.

The game of saqataq is played in the following manner: a knife is laid on the platform and spun round and the person at whom the point is directed when it comes to rest is then laughed at, or must fetch ice etc., is pretty, ugly, or whatever may have been agreed upon in advance. Blind man's buff (taptajaqtut): A man has his eyes blindfolded and must catch another, who receives a blow on the left temple and takes his place.[17] Boas[18] says about the Aiviliks that a musk ox dipper acts as a roulette wheel, being twisted round in a circle by the women and the one from whom the handle points. away, wins.

There are several games which may be included in the term Sport:

Fisticuffs. Was formerly used as a sort of greeting or introduction when a strange tribe was on a visit; it was also practised among the Iglulik Eskimos themselves for the purpose of settling disputes. The method is that two men strike each other, in turn with the closed hand, either on the left temple (quperneq) or on the bare left shoulder (tigdlungneq); the blow is struck with the inner side of the hand and describes a horizontal curve from right to left. The one who holds out longest is the winner. In former days especially these fights often became serious; there still lives an old man on Southampton Island who, in his younger days, killed a Netsilik by a blow on the temple during one of these contests, and it sometimes happened

Image missingFig. 171.

Nuglutang.

that the beaten contestant, exasperated with pain and anger, resorted to the knife.[19] Nowadays it is only the young people who amuse themselves in this manner, and they always stop in good time.

One summer night at Beach Point I saw a number of young people playing, besides fisticuffs: tug-of-war with a length of seal-thong (aqsaraq), at each end of which was a wooden handle, the two contestants sitting on the ground with their feet braced against each other's and pulling on the handles; pulling by locking two fingers together or two arms; with a ring of seal-thong held between them, two men lay on the ground at full length and each tried to draw the other to him; holding each other by the head, each put a finger in the corner of the other's mouth and pulled until one gave up; throwing with stones at a stone set up on a bigger one, or seeing who had the longest throw.

An aqsaraq fron Itibdjeriang consists of two wooden sticks, about 13 cm long, 2½ cm thick, tied together with a strip of walrus hide which rests in grooves and has the ends sewn together; distance between the sticks about 3 cm.

The game of atdlungatoq consists in a thong being stretched. across the snow house, fastened with toggles to the outer side of the house, or it may be stretched outside between two stone pillars. On this thong they do physical exercises: sitting on the thong and bringing the legs over without losing balance, etc., a game that is also spoken of by Hall.[20]

Kalivertartoq: One holds the thin end of the whip and another the handle; in skipping with it, one or two must stand in and jump over the lash so that it passes under them. At Aningatartoq the one who is skipping holds the rope himself.

Ball games are very popular in summer: both men and women, often with children in the back-pouches, take part ant often roll over in a bunch on the grass. There are various games: Ataujartut: there are two sides, and the object is to keep passing the ball to and fro and preventing the opposing side from getting it; the player who has the ball may only retain it a moment; sometimes the men form one side and the women the other. Atariaq: One stands in the middle and the others around him; the ball is knocked alternately to him and to those around him; it must not be held but knocked on immediately. The ball used in these games is usually of seal skin filled with gravel. These national games are now being more and more forced into the background by football and baseball.

Iglukitartut is the name of a ball game with two or three stones, one in one hand and two in the other; these stones are thrown into the air and caught by different hands in turn. When playing piqlertartut they use a small ball of the cartilage of a walrus breast-bone; it is thrown on to the ground and bounces up again; the players sit on the platform and try to catch it and throw it again, but as the floor is uneven, it is very uncertain in which direction it will bounce. Boas[21] figures from the Aiviliks two rings of baleen tied together, which were used as a kind of ball.

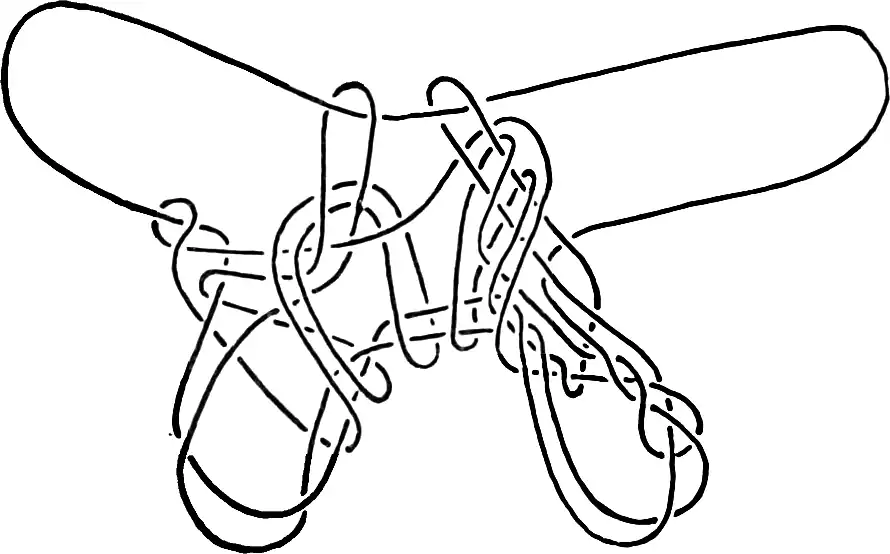

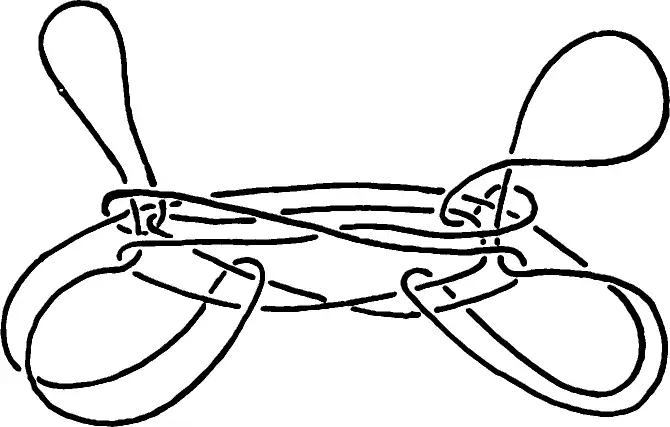

A favourite pastime of the women is "cat's cradle". the making of string figures (ajaragtut); these are also mentioned by Parry.[22] An exhaustive work has recently been published on the string figures of another Central Eskimo tribe, the Copper Eskimos, by D. Jenness[23] and I will therefore limit myself to indicating which of Jenness' figures are included in our collection from the Iglulik Eskimos and to illustrating some figures that are not in Jenness' collection. The following figures from the Iglulik Eskimos are known from the Copper Eskimos; they are given first by the Iglulik-Eskimo name, then follows the meaning of the name, the tribal-group from which we obtained it (Aiv., Igl., Tun.) and finally their number and name in Jenness' work:

- Ukaliartjuk, hare, Aiv. — XXVI, hare.

- Agdlarssuk, brown bear without head, Aiv. Tun. — I. Two brown bears.

- Amarorssuk, wolf, Aiv. — XXVIII wolf.

- Tugtúnguaq, caribou, Aiv. Tun. — XXIV, caribou.

- Tuluarssuk, raven, Aiv. Tun. — XXVII, raven.

- Teriangniarssuk, fox, Aiv. Tun. — XCV, fox.

- Ijitulertjuk, eye, Aiv. Tun. — XXXVI, two large eyes.

- Nugatsiaq, caribou calf, Aiv. — LVII, two calves.

- Nerdleq, goose, Aiv. — CXXXIX, swan.

- Qajaratsiaq, kayak, Tun. — XLVIII, kayak.

- Sagiatsiaq, caribou breast-bone, Tun. — CXLVII, breast bone.

- Qanertjuk, Tun. — XV, anus.

- Tûgalatsiaq, Tun. — LXXVIII, sealhunter.

The following figures differ only slightly from the corresponding figures of the Copper Eskimos:

- Qilaluaq, narwhal, Tun. Aiv. — XLIII whale.

- Qingmeq, dog, Tun. — LXXVIII, sealhunter.

- Ikumaratsiaq, fire on the blubber lamp, Tun. — CIIVI. steep mountain.

The following figures are not included in Jenness' collection from the Copper Eskimos and are therefore figured:

Ilimartuartoq, shaman performance, Tun. Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig. 172. | |

Túgatsiaq, Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 173. | |

Arnajorssuk, goblin woman, Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 174. | |

Seal gut, Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 175. | |

Lemmings (or caribou calves), Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 176. | |

Nivíngarssuartitaq, Aiv. Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 177. | |

Tuluarssuk, raven. Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 178. | |

Ijokarâtsiaq, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 179. | |

Nanortjuk, bear, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 180. | |

Itertjuk, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 181. | |

Ârdlo, killer whale, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 182. | |

Avatatsiaq, harpoon bladder, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 183. | |

Tamanuakataq, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 184. | |

Amaroq, wolf, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 185. | |

Puarqit, snow shovel. Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 186. | |

Qaqbiatiaq, wolverine, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 187. | |

Tûgdlit, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 188. | |

Tulimârssuk, rib, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 189. | |

Qaqârssuk, rock, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 190. | |

Kiasigatsiaq, shoulder blade, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 191. | |

Sêrqutdleq, knee, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 192. | |

Nauja, gull, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 193. | |

Aorrup niaqua, walrus head, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 194. | |

Qilaujaqtoq, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 195. | |

Avingnaratsiaq. lemming, Tun. Aiv. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 196. | |

Teriatsiaq, ermine, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 197. | |

Inuksugatsiaq, cairn, Tun. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Fig.— 198. | |

Dancing (muminguarneq) is one of the greatest pleasures of the Iglulik Eskimos. In former times the dance went on in a special, large snow-house, qâgi. which has been referred to in the foregoing; it was in the severe winter time, whilst they still lived in part upon the supplies left over from the summer and where a number of people lived at the same place, that this dancing took place.

As a rule only the men danced, one at a time; he took the drum and, with a rocking movement, allowed the frame to fall upon the drumstick, he himself swaying his body from side to side and singing; when one man was tired, another continued in his place. I did not find a single drum (qilaut) preserved among the Iglulik Eskimos except as a child's toy. Hall[24] describes the drum of the Aiviliks: A frame of wood or baleen, 2½ inches wide, 1½ inches thick, 3 feet in diameter, covered with caribou skin; when the skin is not in use it is kept frozen; it is saturated with water before being stretched over the frame.

An old man, Ivaluartjuk, described the mask dances which were danced at Iglulik in former days: A man and his wife danced together, the man with a whip in his hand, the woman with a stick. The man had to choose a woman from among the spectators and any woman who wished to be taken whispered his name, whereafter. he touched her with the whip and they went outside together; the wife was supposed to chastise the audience with her stick. Masks of wood or sealskin were used during the dance. Fig. 199 b is the model of a man's mask, of hairy sealskin, oval, with openings for eyes, nostrils and mouth and a prominent, hairless nose; eyebrows. moustache and beard of caribou skin with long hair; Image missingFig. 199.Masks. edged with a narrow strip with the hair-side inwards; 25 cm long. Fig. 199 a is the corresponding woman's mask, of black, unhaired sealskin, with eyebrows of hairy sealskin and tatooing marks of yellow strips of sealskin; prominent nose; 26 cm long.

The dancer was not supposed to laugh, although the audience could do so. The man who had the best meat had to hang it up in the house before the dance began and later on distribute it. At the end of the dance the house was closed and not opened again until another dance was to be held. This dancing was called tivaijoq.

Sometimes during the mask dance an artificial penis was worn; it was connected by a cord with the upper part of the body so that it could be raised and lowered; when it was raised the audience had to laugh; when it was lowered, they had to look grave.

It is now more than twenty years since the last mask dance was held at Iglulik and still longer since the Aiviliks held one. The whaler dances at the trading stations have superseded it.

In summer, when there had been particularly good hunting, great feasts were once held at places surrounded by large stones; it is these which Parry describes from Ungerlôdjan at Iglulik. At several places, for instance at Repulse Bay, we saw such large, four-sided stone walls, but as a rule they seemed to be connected with the Thule culture.

Customs and taboo regulations among the Iglulik Eskimos are dealt with at length in Parry,[25] Klutchak[26] and Boas,[27] the latter according to information supplied by Captain Comer. I myself have never been present at a burial; but through other members of the Expedition and also by means of finds and through the Eskimos. themselves learned to know quite a lot about these matters and I give it here.

When a man has died, there must be no hunting for six days; during the first three days the corpse must lie in the house and is then carried through a hole in the rear wall and buried; during the last three days the relatives must howl at the grave. After the death of a woman there must be no hunting for ten days (5 + 5). The dead person's possessions in the house are taken by a childless woman and laid by the side of the grave. As a rule the burial takes place in the following manner: the corpse is shrouded in caribou skin and laid in the snow some distance from the settlement, snow being piled over it; in most cases the corpse is then torn to pieces and eaten by dogs, wolves or foxes (according to the Eskimos at Repulse Bay). In summer, stones are sometimes piled over, the grave thereby assuming the appearance of an irregular heap of stones.

Freuchen relates of the death of an old woman. Pauti, at Repulse Bay: When she was dead, a hole was made in the tent to allow the soul to escape; a bier was knocked together out of two planks, the corpse was sewn into all the skins in the tent, a large hole was made in the rear wall and the corpse was drawn through it. Four men carried the corpse and two women walked at the sides to see that it did not fall off. They went up over the hills and returned two hours later, the women with the hoods drawn over their heads. The grave was built of stones with turf between them; at one end three stones were placed together for the howlers; the bier lay at the side of the grave. Nobody went hunting during the next few days and the women had not to sew; the mittens and boots used at the burial were thrown away. The two grown-up sons of the deceased wept and howled at the grave, as also did the women in the tent.

It is the exception, however, that a stone grave is made. At Tulugkan. Ponds Inlet, I saw the grave of a little girl, which could not have been very old; no stones at all had been used and the bones, which still had the pellicle on them, lay spread about, while there were only small pieces and some hair of the caribou skin in which the body had been shrouded. In a crack in the cliff close by were the grave goods: a small, square cooking pot of sheet iron containing: an enamelled cup, iron spoon, two small wooden dolls, a small ulo, little bead necklace, small cardboard box, a fragment of newspaper, small piece of pencil, a safety pin and a match.

A rather older grave of a man at Moffet Inlet. in Admiralty Inlet, examined by Freuchen, contained: A flat harpoon head with iron blade, two spurs, no barbs; three rests for the ice-hunting harpoon; six pieces of composite bows of antler: a marline spike: five arrow Regarding older grave finds which belong to the same culture, however, see "Archaeology of the Central Eskimos", Pl. 66.

- ↑ Parry 1824 p. 378.

- ↑ Lyon 1824 p. 293.

- ↑ Lyon 1. c. p. 296.

- ↑ 1824 p. 528.

- ↑ 1824 p. 531.

- ↑ 1824, p. 173.

- ↑ 1824 p. 120.

- ↑ See Lyon 1824 p. 288.

- ↑ 1924 p. 35.

- ↑ 1824 p. 550.25.

- ↑ 1888 fig. 522.

- ↑ 1901 p. 111.

- ↑ 1879 p. 95.

- ↑ Cf. Boas 1901 fig. 163–64 and 1907 fig. 221 a–c.

- ↑ p. 232.

- ↑ Cf. Boas 1888 fig. 523.

- ↑ Cf. Boas 1901 p. 112.

- ↑ l. c. p. 110.

- ↑ Boas 1901 p. 116.

- ↑ p. 95.

- ↑ 1901 fig. 161.

- ↑ 1824 p. 293.

- ↑ 1925.

- ↑ 1879 p. 97.

- ↑ 1824 pp. 390, 393, 401, 551.

- ↑ p. 208.

- ↑ 1907 pp. 515–17.