Life Movements in Plants Vol 1/Chapter 9

IX.—MODIFYING INFLUENCE OF TONIC CONDITION ON RESPONSE

By

Sir J. C. Bose,

Assisted by

Guruprasanna Das.

In experiments with different pulvinated organs, great difference is noticed as regards their excitability. If electric shock of increasing intensity from a secondary coil be passed through the pulvini of Mimosa, Neptunia, and Erythrina arranged in series, it would be found that Mimosa would be the first to respond; a nearer approach of the secondary coil to the primary would be necessary for Neptunia to show sign of excitation. Erythrina would require a far greater intensity of electric shock to induce excitatory movement. Organs of different plants may thus be arranged, according to their excitability, in a vertical series, the one at the top being the most excitable. The specific excitability of a given organ is different in different species.

In addition to this characteristic difference, an identical organ may, on account of favourable or unfavourable conditions, exhibit wide variation in excitability. Thus under favourable conditions of light, warmth and other factors, the excitability of an organ is greatly enhanced. In the absence of these favourable tonic conditions the excitability is depressed or even abolished. I shall, for convenience, distinguish the different tonic conditions of the plant as normal, hyper-tonic and sub-tonic. In the first case, stimulus of moderate intensity will induce excitation; in the second, the excitability being exceptionally high, very feeble stimulus will be found to precipitate excitatory reaction. But a tissue in a sub-tonic condition will require a very strong stimulus to bring about excitation. The excitability of an organ is thus determined by two factors: the specific excitability, and the tonic condition of the tissue.

THEORY OF ASSIMILATION AND DISSIMILATION.

A muscle contracts under stimulus; this is assumed to be due to some explosive chemical change which leaves the tissue in a condition less capable of functioning, or in a condition below par. Herring designates this as a process of dissimilation. The excitability of the muscle is restored after suitable periods of rest, by the opposite metabolic change of assimilation. "Assimilation and Dissimilation must be conceived as two closely interwoven processes, which constitute the metabolism (unknown to us in its intrinsic nature) of the living substance. Excitability diminishes in proportion with the duration of D-stimulus, or, as it is usually expressed, the substance fatigues itself. It is perfectly intelligible that a progressive fatigue and decrement of the magnitude of contraction must ensue. The only point that is difficult to elucidate is the initial staircase increment of the twitches, more especially in excised, bloodless muscle, which seems in direct contradiction with the previous theory."[1]

With reference to Herring's theory given above, Bayliss in his "Principles of General Physiology" (1915), page 377 says, "In the phenomenon of metabolism, two processes must be distinguished, the building up of a complex system or substance of high potential energy, 'anabolism,' and the breaking down of such a system 'catabolism,' giving off energy in other forms. The tendency of much recent work, however, is to throw doubt on the universality of this opposition of anabolism and catabolism as explanatory of physiological activity in general."

The results obtained with the response of plants to stimulus may perhaps throw some light on the obscurities that surround the subject. They show that the two processes may be present simultaneously, and that the 'down' change induced by stimulus may, in certain instances, be more than compensated by the 'up' change.[2] I shall, for convenience, designate the physico-chemical modification, associated with the excitatory negative mechanical and electrical response of plants, as the "D" change; this is attended by run down of energy. The positive mechanical and electrical response must therefore connote opposite physico-chemical change, with increase of potential energy. This I shall designate as the "A" change, which by increasing the latent energy, enhances the functional activity of the tissue. That stimulus may give rise simultaneously to both A, and D, effects, finds strong support in the dual reactions exhibited in plant-response. Under indirect stimulus, the two responses are seen separately, the more intense negative following the feeble positive. When by the reduction of the intervening distance, stimulus is made direct, the resultant response, as previously stated, is negative; and this is due not to the total absence of the positive but to its being masked by the predominant negative. Let us next consider the question of unmasking this positive element in the resultant negative response.

UNMASKING OF THE POSITIVE EFFECT.

Under favourable conditions of the environment, the excitability of the organs is at its maximum. A given stimulus will bring about an intense excitation, and the 'down' D-change will therefore be very much greater than the A-change. Let us now consider the case at the opposite extreme where, owing to unfavourable condition, the excitability is at its lowest. Under stimulus the excitatory D-change will now be relatively feeble compared to the A-change, by which the potential energy of the system becomes increased. In such a case successive stimuli will increase the functional activity of the tissue, and bring about staircase response. Biedermann mentions the staircase response of excised bloodless muscle as offering difficulty of explanation. It is obvious that the physiological condition of the excised muscle must have fallen below par. The staircase response in such a tissue is thus explained from considerations that have just been adduced.

The results obtained with Mimosa not only corroborate them, but add incontestable proof of the simultaneous existence of both A and D changes. The physiological condition of a plant, Mimosa for example, is greatly modified by the favourable or unfavourable condition of the environment. In a hyper-tonic condition its excitability becomes very great; in this condition the plant responds to its maximum even under very feeble stimulus. Here the D-change is relatively great, and successive responses are apt to show sign of fatigue.

But the plant in a sub-tonic condition will exhibit feeble or no excitation. The D-change will be absent while the A-change will take place under the action of stimulus. This, by increasing the potential energy, will enhance the functional activity of the tissue.

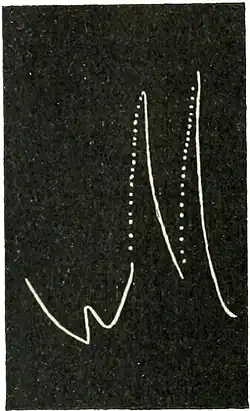

Staircase response in Mimosa: Experiment 48.—The theoretical considerations will be found experimentally verified in the record obtained with a specimen of Mimosa in a sub-tonic condition (Fig. 53).

Fig. 53.—Record showing the effect of stimulus modifying tonicity and producing staircase effect. (Mimosa.) Owing to the lack of favourable 'tone' the leaf was relaxing as seen in the first part of the curve. The stimulus of electric shock, applied at the thick dot in the curve slanting downwards, gave no response but raised the tone of the tissue by arresting the growing relaxation. Subsequent stimuli gave rise to staircase responses. Stimulus has, through the A-effect, raised the functional activity of the tissue to a maximum.

ARTIFICIAL DEPRESSION OF TONIC CONDITION AND MODIFICATION OF RESPONSE.

It has been shown that while favourable tonic condition has the effect of raising the excitability and enhancing the negative response with the associated D-change, a condition of sub-tonicity, on the other hand, induces depression of excitability, a diminution of negative response and of the attendant D-change. In this condition the positive element in the response with the A-change will come into greater prominence. These considerations led me to experiment with specimens exhibiting increasing sub-tonicity, with a view of ummasking the positive element in the response, i.e., the A-change. In the last experiment a specimen was found which happened to be in a sub-tonic condition on account of the unfavourable condition of its surroundings. I was next desirous of securing specimens in which I could induce increasing sub-tonicity at will.

I have shown (Expt. 23) that a detached branch of Mimosa can be kept alive for several days with the cut end immersed in water. In this condition the pulvinus retains its sensitiveness for more than two days. The excitability undergoes a continuous decline and is abolished about the fiftieth hour. Isolation from the parent organism thus causes a continuous depression of the tonic condition of the specimen. The case is somewhat analogous to the depression of excitability in an excised bloodless muscle. It is thus possible to secure specimens of varying degrees of sab-tonicity. A specimen that has been detached for six hours will exhibit a slight amount of depression, while a different specimen isolated for twenty-four hours will occupy a very much lower position in the scale of tonicity.

Experiment 49.—The staircase response of Mimosa given in figure 53 was obtained with the stimulus of induction shock. In order to establish a wider generalisation I now used the stimulus of light given by an arc lamp. There may be a difficulty on account of the diurnal movement of Mimosa; the leaf, generally speaking, has a movement in a downward direction from morning till noon, after which there is a comparative state of rest. It is better to choose the time of noon for experiment. In any case the response to stimulus is very abrupt and in strong contrast with the slow diurnal movement. A horizontal pencil of light was thrown upwards by means of a small mirror and made to fall on the lower half of a pulvinus of the Mimosa leaf. The excitatory down movement is followed by recovery on the cessation of light. The intensity of stimulus can be modified by varying the intensity of light. I took for my first series of experiments a specimen that had been isolated for six hours. Stimulation was caused by successive applications of light for 25 seconds at intervals of 3 minutes. Figure 54 shows how the functional activity of the sub-tonic specimen is enhanced by stimulus, the successive responses thus exhibiting the staircase effect.

Fig. 54.

Fig. 55.

Fig. 54.—Staircase response in sub-tonic Mimosa.

Fig. 55.—Positive, diphasic and negative response under successive stimulation.

POSITIVE RESPONSE IN SUB-TONIC SPECIMEN.

Experiment 50.—A still lower degree of sub-tonicity was ensured by keeping the specimen in an isolated condition for 12 hours. Stimulus of light for 20 seconds' duration was applied at intervals of 2 minutes. In the record (Fig. 55) the first two responses, not shown, were purely positive. The third exhibited a positive A-effect, followed by the negative response D-effect. The A-effect is thus seen fully unmasked. In subsequent responses the A-effect became more and more overshadowed by the D-effect. At the third response the masking is complete and the excitatory negative response is at its maximum. The record of staircase effect (Fig. 54) also exhibits a preliminary positive twitch at the beginning of the series, which disappeared after the second response.

The modifying influence of tonic condition on response I find to be of universal occurrence. In vigorous specimens the electric response to stimulation is negative; but tissues in sub-tonic condition give positive response and after long-continued stimulation the abnormal positive is converted into the normal negative. It is very interesting that under condition of sub-tonicity diverse expressions of physiological reaction exhibit similar change of sign of normal response. Thus in my measurement of the velocity of transmission of excitation in the conducting tissue of Mimosa, I find that, when the tissue is in an optimum condition, exhibiting high velocity of transmission, excessive stimulus has the effect of diminishing the conducting power. But in a depressed condition of the tissue the effect is precisely the opposite. Thus in a given case the velocity of transmission was low; strong electric stimulation enhanced the rate by 33 per cent. In extreme cases of sub-tonicity, where the conducting power was in abeyance, the excessive stimulus caused by wound not only restored the power of conduction but raised the velocity of transmission to 25 mm. per second (Expt. 37).

SUMMARY.

The excitability of a plant is found to be modified by its tonic condition.

A sub-tonic specimen of Mimosa, like an excised bloodless muscle, shows a preliminary staircase response. Stimulus induces simultaneously both "A" and "D" effects, with their attendant positive and negative reactions.

A tissue in optimum condition exhibits only the resultant negative response, the comparatively feeble positive being masked by the predominant negative. With decline of tone, the "D" effect diminishes and we get "A" effect unmasked.

In extreme sub-tonic specimen, we get first only the "A" effect, with its positive response. Successive stimulation converts the pure positive into diphasic and ultimately into normal negative response.

- ↑ Biedermann—Electro-Physiology (English Translation), Vol 1, pp. 83, 84, 5; Macmillan & Co.

- ↑ In the response of inorganic matter I have obtained records of positive, diphasic and negative responses. It would perhaps be advisable to refer the 'A' and 'D' effects, to physico-chemical change. The simultaneous double reaction, combination and decomposition, is of frequent occurrence in many chemical changes.