Life Movements in Plants Vol 1/Chapter 21

XXI.—A COMPARISON OF RESPONSES IN GROWING AND NON-GROWING ORGANS

By

Sir J. C. Bose,

Assisted by

Guruprasanna Das.

I have in the preceding series of Papers demonstrated the effects of various forms of stimuli on growth. I have also given accounts of numerous reactions which are extraordinarily similar, in growing and non-growing organs. In fact certain characteristic reactions observed in motile pulvinus of Mimosa and other 'sensitive' plants led to the discovery of the corresponding phenomena in growing organs. For fully realising the essential similarity of responses given by all plant-organs, growing and non-growing, I shall give here a short review of the striking character of the parallelism.

- The incipient contraction of a growing organ under stimulus culminates in a marked shortening of the organ.

- The similarity of contractile responses in growing and pulvinated organs.

- Similar modification of both under condition of sub-tonicity.

- The opposite effects of Direct and Indirect stimulus, both in motile and in growing organs.

- The exhibition by all plant-organs of negative electric response under Direct, and positive electric response under Indirect stimulus.

- Similar modification of autonomous activity in Desmodium gyrans and in growing organs under parallel conditions.

- Similar excitatory effects of various stimuli on pulvinated and growing organs.

- Similar discriminative effects of different rays of light in excitation of motile and growing organs.

CONTRACTILE RESPONSE OF GROWING AND NON-GROWING ORGANS.

I have shown (page 198) that a growing organ under stimulus, undergoes an incipient contraction as shown in the responsive retardation of its rate of growth; that this retardation increases with the intensity of the incident stimulus till growth becomes arrested. Above this critical intensity the induced contraction causes an actual shortening of the organ. There is no breach of continuity in the increasing contractile reaction, which at various stages appears as a retardation, an arrest of growth or a marked shortening of length of the organ.

CONTRACTILE RESPONSE OF PULVINATED AND GROWING ORGANS.

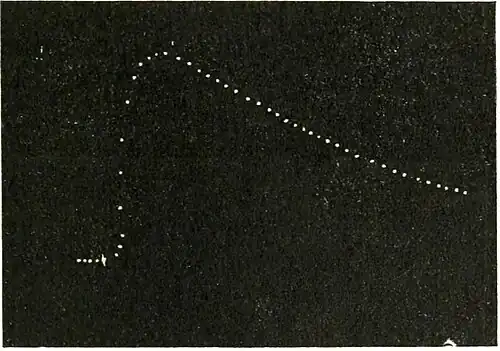

Experiment 94.—In order to show the striking similarity between the response of 'sensitive' Mimosa and that of a growing organ, I give a record (Fig. 88) obtained with a

Fig. 88.—Contractile response of growing organ under electric shock. Successive dots at intervals of 4″. Vertical lines below represent intervals of one minute. (Magnification 1,000 times.)

growing bud of Crinum under the stimulus of electric shock above the critical intensity. The recorder gave a magnification of a thousand times. In Fig. 88, the normal growth elongation is represented as a down-curve. On the application of stimulus the normal expansion was suddenly reversed to excitatory contraction, the latent period of reaction was one second and the period of the attainment of maximum contraction (apex-time) was 4 minutes. The organ recovered its original length after a further period of seven minutes and then continued its natural growth elongation. Repetition of stimuli gave rise to successive contractile responses which are in every way similar to the mechanical responses of Mimosa pudica. The essential similarity of response of pulvinated and growing organs will be seen in the following tabular statement:

TABLE XXI.—TIME RELATIONS OF MECHANICAL RESPONSE OF PULVINATED AND GROWING ORGANS.

| Specimen. | Latent period. | Apex-time. | Period of recovery. |

Motile pulvinus of Mimosa pudica. … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … |

0.1 sec. | 1803 secs. | 16 minutes. |

Motile pulvinus of Neptunia oleracea. … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … |

0.6 sec.„ | 180 secs.„ | 60 minutes.„ |

Growing bud of Crinum … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … |

1.0 sec.„ | 240 secs.„ | 607 minutes.„ |

The contraction in growing organs under stimulus is sometimes considerable. Thus in the filamentous corona of Passiflora quadrangularis the contraction may be as much as 15 per cent. of the original length. This is not very different from the excitatory reaction of the typically sensitive stamens of the Cynereæ, which exhibits a contraction from 8 to 22 per cent.

MODIFICATION OF RESPONSE BY CONDITION OF SUB-TONICITY.

In Mimosa the normal response to direct stimulus is negative, the leaf undergoing a fall. But sub-tonic specimens exhibit a positive response with erection of the leaf. The action of the stimulus itself improves the tonic condition, and the abnormal positive is thus converted into normal negative, through diphasic response (p. 147). Similarly in growing organs, while the normal effect of stimulus is incipient contraction and retardation of growth under condition of sub-tonicity the response is by acceleration of growth. Continuous stimulation converts this abnormal acceleration into normal retardation of growth (p. 225).

EFFECTS OF DIRECT AND INDIRECT STIMULUS.

Direct stimulus induces in Mimosa and other 'sensitive' plants a negative response. There is a diminution of turgor and contraction in the motile organ, resulting in the fall of leaf. Indirect stimulus, on the other hand, gives rise to a positive or erectile response, indicative of increase of turgor and expansion (p. 138).

In growing organs Direct stimulus induces an incipient contraction and retardation of rate of growth; the effect of Indirect stimulus is expansion and accelaration of the rate of growth (p. 216).

The opposite reactions to Direct and Indirect stimulus are also found in the electric response given by all plant organs. Thus while Direct stimulus induces an electromotive change of galvanometric negativity, Indirect stimulus induces the opposite change of galvanometric positivity (p. 214).

MODIFICATION OF AUTONOMOUS ACTIVITY.

The autonomous activity of Desmodium gyrans exhibited by the pulsation of its leaflets come to a stop under condition of sub-tonicity. The arrested movement is, however, revived by the action of stimulus (p. 228). The depressed or arrested growth of a growing organ is similarly accelerated or revived by the action of stimulus (p. 230).

In vigorous specimens stimulus induces the opposite effect by retarding or arresting the pulsatory activity or growth.

Warmth induces an effect which is antagonistic to that of stimulus. The contractile effect of stimulus is seen in the pulsations of leaflet Desmodium by the reduction of their expansive or diastolic limit, and in growing organs by the retardation of the rate of growth. The expansive effect of warmth is seen in reduction of the systolic limit of Desmodium pulsation, and in the acceleration of rate of growth in growing organs (p. 237).

EXCITATORY EFFECTS OF VARIOUS STIMULI ON PULVINATED AND GROWING ORGANS.

Certain agents induce excitation in living tissues, the excitatory change being detected by contraction, or by electromotive variation, or by change of electric resistance, and in growing organs by the retardation of the rate of growth. In general, the various stimuli which excite animal tissues also excite vegetable tissues.

It has been shown that every form of stimuli, however diverse, also induces incipient contraction and retardation of the rate of growth. Thus mechanical irritation, such as friction or wound, induces a retardation of growth (p. 202); they also induce an excitatory contraction in Mimosa, attended by the fall of the leaf. Different modes of electric stimulation act similarly on both growing and pulvinated organs. The action of light visible and invisible will presently be seen to react on both alike. And in this connection nothing could be more significant than the discriminative manner in which both the pulvinated and the growing organs respond to certain lights and not to others.

In contrast to the contractile effect of stimulus, certain agents induce the antagonistic reaction of expansion. It has been shown that while stimulus induces a retardation, rise of temperature up to an optimum point, induces an acceleration of the rate of growth. I have also referred to the fact that while the autonomous pulsations of Desmodium leaflet exhibit under stimulus a diminution of the extent of the diastolic expansion, warmth on the other hand, induces the opposite effect by diminishing the systolic contraction.

EFFECT OF LIGHT ON PULVINATED ORGANS.

I have referred to the well-known fact that it is the more refrangible portions of the spectrum that are more effective in inducing excitatory reactions and have already given records of the responsive reactions of various lights on growing organs. I shall now give records of the effect of various lights on the pulvinus of Mimosa pudica. The amplitude and time relations of the curves of response will give a more precise idea of the quantitative effects of various lights in inducing excitation.

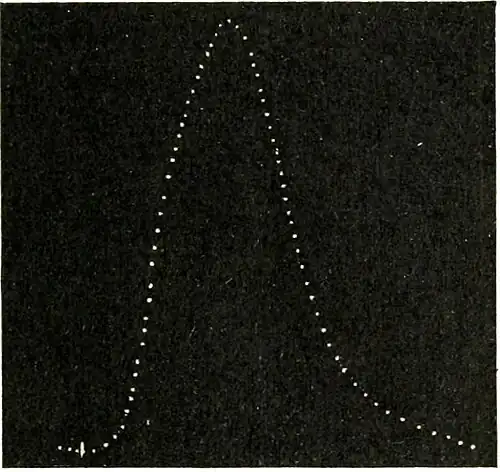

Action of white light: Experiment 95.—The source of light was an arc lamp; a pencil of parallel light is made to pass through a trough of alum solution. This process of excluding thermal rays is adopted for the visible rays of the spectrum. Colour filters were also used for obtaining red, yellow and blue lights. The pencil of light is thrown upwards by an inclined mirror on the lower half of the pulvinus. The response is taken by an Oscillating recorder, giving successive dots at intervals of 10 seconds, the magnification employed being 100 times. The pulvinus being subjected to light for 10 seconds gave response by a fall of the leaf (Fig. 89). The response to light

Fig. 89.—Effect of white light on the pulvinus of Mimosa. Successive dots in this and in the following records are at intervals of 10″. (Magnification 100 times).

is thus found to be essentially similar to that induced by electric stimulus, the only difference being in the relative sluggishness of the reply. Electric shock passes instantaneously through the mass of the pulvinus, stirring up the active tissues to responsive contraction. The latent period is, therefore, as short as 0.1 second and the maximum contraction is effected in about 3 seconds. In the case of the stimulus of light the shock-effect is not so great; excitation, moreover, has to pass slowly from the surface of the pulvinus inwards. Hence the latent period is twelve seconds, and the period of maximum contraction is as long as 90 seconds. As the stimulation is moderate, the recovery is effected in 11 minutes, instead of 16 minutes, which is the usual period for Mimosa to recover from an electric shock. The important conclusion to be derived from this experiment is that light is a mode of stimulation end that it induces a responsive contraction, similar to that caused by other forms of stimuli. This contractile response under light is exhibited not merely by the motile pulvinus of Mimosa, but by other pulvini as well, such as those of Erythrina indica, and of the ordinary bean plant.

Action of red and yellow lights.—The pulvinus gave little or practically no response to these lights.

Action of blue light: Experiment 96.—Light was applied for 10 seconds and the amplitude of response was similar to that induced by white light (Fig. 90).

Fig. 90.—Effect of blue light on pulvinus of Mimosa.

Action of Ultra-violet rays: Experiment 97.—The source of light was a quartz mercury-vapour lamp. The effect was so intense that, to keep the record within the plate, I had to reduce the period of exposure to half, i.e., to five seconds. The responsive movement was initiated within six seconds of the application of light. The intensity and the rapidity of reaction is independently evidenced by the more erect curve of response (Fig. 91).

Fig. 91.—Effect of ultra-violet rays on the pulvinus of Mimosa

Action of Infra-red rays: Experiment 98.—The obscure thermal rays also caused a strong excitatory reaction (Fig. 92). Attention is here drawn once more to the antagonistic reactions of temperature and radiation effects of heat.

It has been shown that the rays which cause the most intense excitations in Mimosa also induce the greatest retardation in the rate of growth. Thus ultra-violet is not only the most effective in causing excitation in Mimosa but also in retardation of growth. Next in order comes the blue rays: the yellow and red are practically ineffective in both the cases. Infra-red rays are, however, very effective in exciting the sensitive Mimosa and in retarding the rate of growth.

Fig. 92.—Effect of infra-red rays on the pulvinus of Mimosa.

DIVERSE MODES OF RESPONSE TO STIMULUS.

In Mimosa excitation is followed by the striking manifestation of the fall of the leaf. But in rigid trees contraction under excitation cannot find expression in movements. I have shown elsewhere that even in the absence of realised movement, the state of excitation can be detected by the induced electro-motive change. I have shown that not only every plant but every organ of every plant is sensitive and reacts to stimulus by electric response of galvanometric negativity.[1]

There is an additional electric method by which the excitatory change may be recorded. I find that excitation induces a variation of the electrical resistance of a vegetable tissue.[2] Thus the same excitatory reaction finds diverse concomitant manifestations, in diminution of turgor, in movement, in variation of growth, and in electrical change. The correspondence in the different phases of response in pulvinated, ordinary, and growing organs may be stated as follows: Excitation induces diminution of turgor, contraction and fall of the leaf of Mimosa; it induces an incipient contraction or retardation of rate of growth in a growing organ; it gives rise in all plant organs to an electric response of galvanometric negativity and of changed resistance. All these excitatory manifestations will, for convenience, be designated as the negative response. There is a responsive reaction which is opposite to the excitatory change described above. In Mimosa the fall of leaf under excitation is due to a sudden diminution of turgor; the erection of the leaf is brought about by natural or artificial restoration of turgor. Rise of temperature induces an expansive reaction which is antagonistic to that induced by stimulus. Warmth also enhances the rate of growth and induces an electric change of galvanometric positivity.[3] The restoration of normal turgor or enhancement of turgor is associated with expansion, erection of the leaf of Mimosa, enhancement of rate of growth in a growing organ, electric response of galvanometric positivity, and contrasted change of electric resistance. All these will be distinguished as positive response.

There are thus several independent means of detecting the excitatory change or its opposite reaction in vegetable tissues. It will be seen that the employment of these different methods has greatly extended our power of investigation on the phenomenon of irritability of plants.

We have seen how essentially similar are the responsive reactions in pulvinated and in growing organs. It is therefore rational to seek for an explanation of a particular movement in a growing organ from ascertained facts relating to the corresponding movement in a pulvinated organ. The investigations on motile and growing organs that have been described fully establish the two important facts that, Direct stimulus induces contraction and Indirect stimulus induces the opposite expansive reaction. These facts will be found to offer full explanation of various tropic curvatures to be described in the subsequent series of Papers.

SUMMARY.

There is no breach of continuity in the increasing contractile reaction in a growing organ under increasing intensity of stimulus; the incipient contraction seen in retardation of rate of growth culminates in a marked shortening of the length of the organ.

Time relations of response, the latent period, the apex time, and the period of recovery are of similar order in pulvinated and in growing organs.

In condition of sub-tonicity the pulvinus of Mimosa responds to stimulus by an abnormal positive or erectile response. Under continued stimulation the abnormal positive is converted into normal negative. Growing organs in sub-tonic condition responds to stimulus by abnormal acceleration of rate of growth, which is converted into normal retardation under continuous stimulation.

Direct stimulus induces in Mimosa a negative response, with the fall of leaf. But Indirect stimulus induces the positive or erectile response. Similarly, Direct stimulus induces in a growing organ a negative variation, or retardation of rate of growth, and Indirect stimulus a positive variation or acceleration of rate of growth.

The electric response to Direct stimulus is by galvanometric negativity, that to Indirect stimulus by galvanometric positivity.

Under condition of sub-tonicity the autonomous activity of leaflet of Desmodium gyrans and of growing organs comes to a stop. The arrested activity in both is revived by the application of stimulus. Active pulsation in Desmodium, and active growth in growing organs are, however, retarded or arrested by stimulus.

The contractile effect of stimulus on pulsation of leaflets of Desmodium gyrans is seen by the reduction of the diastolic limit of its pulsations; to this corresponds the incipient contraction and retardation of rate of growth in a growing organ. The effect of warmth is antagonistic to that of stimulus. The expansive effect of rise of temperature is seen in Desmodium by the reduction of the systolic limit of its pulsation; in growth it is exhibited by an acceleration of the rate of growth.

All stimuli which induce an excitatory contraction and fall of the leaf of Mimosa also induce incipient contraction and retardation of rate of growth in a growing organ.

Excitatory effects of different rays of light on motile and growing organs are similarly discriminative. Ultra-violet light exerts the most intense reaction which reaches a minimum towards the less refrangible red end of the spectrum. Beyond this, the infra-red or thermal rays become suddenly effective in inducing excitatory movement and retardation of growth.