Life Movements in Plants Vol 1/Chapter 10

December 1918.

PART II.

GROWTH AND ITS RESPONSIVE VARIATIONS.

X.—THE HIGH MAGNIFICATION CRESCOGRAPH FOR RESEARCHES ON GROWTH[1]

By

Sir J. C. Bose,

Assisted by

Guruprasanna Das, l.m.s.

In discussing the difficulties connected with investigations relating to longitudinal growth and its variations, Special stress must be laid on the importance of maintaining external conditions absolutely constant. This constancy can only be maintained in practice for a short time. Lengthy periods of observation, moreover, introduce the uncertainty of complication arising from spontaneous variation of growth. The possibility of accurate investigation, therefore lies in reducing the period of the experiment to a few minutes during which we have to determine the normal rate of growth and its variation under a given changed condition. This would necessitate the devising of a method of very high magnification for record of the rate of growth.[1]

With auxanometers now in use, which give a magnification of about twenty times, it takes nearly four hours to determine the influence of changed condition in inducing variation of growth. It will be seen that if we succeeded in enhancing magnification from twenty to ten thousand times, the necessary period for experiment would be reduced from four hours to thirty seconds. The importance of securing a magnification of this order is sufficiently obvious.

The problem of high magnification was first solved by my Optical Lever.[2] The tip of the growing organ was attached to the short arm of a lever, the axis of which carried a small mirror; in this way it was possible to obtain a magnification of a thousand times. The magnified movement of growth was followed with a pen on a revolving drum. The record laboured under the disadvantage of not being automatic. This defect was overcome by the use of the photographic method which however entailed the inconvenience and discomfort of a dark room.

I have, for the past six years, been working with a different method, which has now been brought to a great state of perfection. The problem to be solved was the devising of a direct method of high magnification and the automatic record of the magnified rate of growth.

METHOD OF HIGH MAGNIFICATION.

The magnification in my Crescograph is obtained by a compound system of two levers. The growing plant is attached to the short arm of a lever, the long arm of which is attached to the short arm of the second lever. If the magnification by the first lever be m, and that by the second, n, the resulting magnification would be mn.

The practical difficulties met with in carrying out this idea are very numerous. It will be understood that just as the imperceptible movement is highly magnified by the compound system of levers, the various errors and difficulties are likely to be magnified in the same proportion. The principal difficulties met with were due: (1) to the weight of the compound lever which exerted a great tension on the growing plant, (2) to the yielding of flexible connections by which the plant was attached to the first lever, and the first lever to the second, and (3) to the friction at the fulcrums.

Weight of the Lever.—As the first lever is to exert a pull on the second, it has to be made rigid. The second lever serves as an index, and can therefore be made of fine glass fibre. The securing of rigidity of the first lever entails large cross section and consequent weight, which exerts considerable tension on the plant. Excessive tension greatly modifies growth; even the weight of the index used in self-recording auxanometers is found to modify the normal rate of growth. The weight of the levers introduces an additional difficulty in the increased friction at the fulcrums, on account of which there is an obstruction of the free movement of the recording arm of the lever. The conditions essential for overcoming these difficulties therefore are: (1) construction of a very light lever possessing sufficient rigidity, and (2) arranging the levers in such a way that the tension on the plant may be reduced to any extent, or even eliminated.

I found in navaldum, an alloy of aluminium, a light material possessing sufficient rigidity. The first lever is constructed out of a thin narrow sheet 25 cm. in length; it has, as explained before, to be fairly rigid in order to exert a pull on the second without undergoing any bending; this rigidity is secured by giving the thin narrow plate of the lever a T-shape. The first lever balances, to a certain extent, the second. Finer adjustments are made by means of an adjustable counterpoise B, at the end of the levers. By this means the tension on the plant can be greatly reduced; or a constant tension may be exerted by means of a weight T (Fig. 56). In my later type

Fig. 56.—Compound lever. P, plant attached to short arm of lever L; T, weight exerting tension; C, connecting link; L′, second lever with bent tip for record; B, B, balancing counterpoise. Fork F, carries at its side two conical agate cups, on which lever rests by two pin-points. (From a photograph.)

of the apparatus the plant connection is made to the right, instead of the left side of the first fulcrum. This gives certain practical advantages. The second lever is then made practically to balance the first, only a very slight weight being necessary for exact counterpoise. The reduction of total weight thus secured reduces materially the friction at the fulcrum with great enhancement of efficiency of the apparatus.

The second or the recording lever has a normal excursion through 8 cm. on the recording surface, which is a very thin sheet of glass 8×8 cm. coated with a layer of smoke. As the recording lever is about 40 cm. in length, the curvature in the record is slight, and practically negligible in the middle portion of 4 cm. The dimensions given allow a magnification of ten thousand times. A far more compact apparatus is made with 15 cm. length of levers. This gives a magnification of a thousand times.

AUTOMATIC RECORD OF THE RATE OF GROWTH.

Another great difficulty in obtaining an accurate record of the curve of growth arises from the friction of contact of the bent tip of the writing lever against the recording surface. This I was able to overcome by an oscillating device by which the contact, instead of being continuous, was made intermittent. The smoked glass plate, G, is made to oscillate, to and fro, at regular intervals of time, say one second. The bent tip of the recording lever comes periodically in contact with the glass plate during its extreme forward oscillation. The record would thus consist of a series of dots, the distance between successive dots representing magnified growth during a second.

The drawback in connection with the obtaining of record on the oscillating plate lies in the fact that if the plate approaches the recording point with anything like suddenness, then the stroke on the flexible lever causes an after-oscillation; the multiple dots, thus produced, spoil the record. In order to overcome this, a special contrivance is necessary, by which the speed of approach of the plate should be gradually reduced to zero at contact with the recording point. The rate of recession should, on the other hand, continuously increase from zero to maximum. The recording point will in this manner be gently pressed against the glass plate, marking the dot, and then gradually set free. It was only after strict observance of these conditions that the disturbing effect of after-vibration of the lever could be obviated.

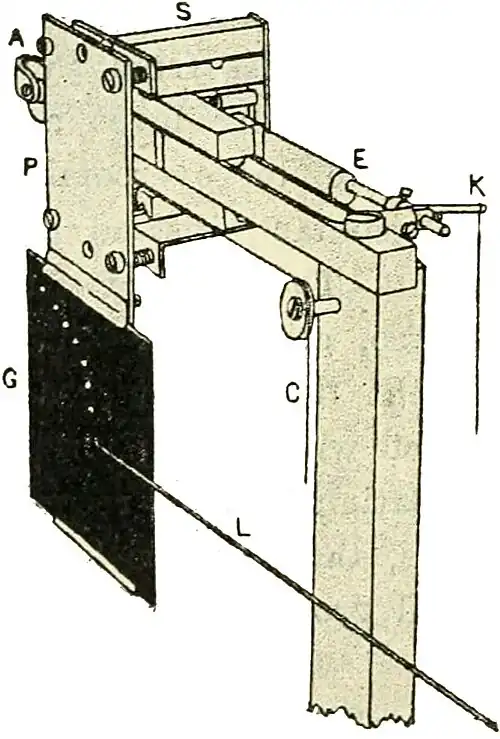

This particular contrivance consists of an eccentric rod actuated by a rotating wheel. A cylindrical rod is supported eccentrically, so that semi-rotation of the eccentric causing a pull on the crank K (Fig. 57) pushes the plate

Fig. 57.—Eccentric for oscillation of plate. K, crank; S, slide; P, holder for glass plate G. A, adjusting screws; L, recording lever. Clock releases string C for lateral movement of the plate. (From a photograph.)

carrier gradually forward. On the return movement of the eccentric, a light antagonistic spring makes the plate recede. The rate of the movement, of the crank itself is further regulated by the device of the revolving wheel. This is released periodically by clockwork at intervals of one, two, five, ten, or fifteen seconds respectively, according to the requirements of the experiment. The complete apparatus is shown in figure 58.

Fig. 58.—Complete apparatus. P, plant; S, micrometer screw for raising or lowering the plant; C, clockwork for periodic oscillation of plate; W, rotating wheel. V, cylindrical plant-chamber. (From a photograph.)

Connecting links.—Another puzzling difficulty lay in the fact that the magnification actually obtained was sometimes very different from the calculated value. This unreliability I was able to trace to the defects inherent in thread connections, employed at first to attach the plant to the first lever, and the first lever to the second. These flexible connections were found to undergo a variable amount of elastic yield. Hence it became necessary to use nothing but rigid connections. The plant attachment, A, of triangular shape is made of a piece of navaldum; its knife-edge rests on a notch at the short arm of the lever, L. There are several notches at various distances from the fulcrum. It will be understood how the magnification can be modified by moving A, nearer or further from the fulcrum. The lower end of the attachment is bent in the form of a hook. The end of the leaf of the plant P, is doubled on itself and tied. The loop thus formed is then slipped over the hooked end of A.

The link, C, connecting L and L′ consists of a pin pointed at both ends, which rests on two conical agate cups fixed respectively to the upper and lower surfaces of the levers L and L′. This mode of frictionless linking is rigid and allows at the same time perfectly free movement of the levers.

The fulcrum.—The most serious difficulty was in connection with frictionless support of the axes of the two levers. The horizontal axis was at first supported on jewel bearings, with fine screw adjustment for securing lateral support. Any slight variation from absolute adjustment made the bearing either too loose or too tight, preventing free play of the lever. When perfect adjustment was secured by any chance, the movement of the levers became jerky after a few days. This I afterwards discovered was due to the deposit of invisible particles of dust on the bearings. These difficulties forced me to work out a very perfect and at the same time a much simpler device. The lever now carries two vertical pin-points which are supported on conical agate cups. The axis of the lever passes through the points of support. The friction of support is thus reduced to a minimum. The levers are kept in place under the constant pressure of their own weight. The excursion of the end of the recording lever, which represents magnified movement of growth, was now found to be without jerk and quite uniform.

EXPERIMENTAL ADJUSTMENTS.

The soil in a flower pot is liable to be disturbed by irrigation, and the record thus vitiated by physical disturbance. This is obviated by wrapping a piece of cloth round the root imbedded in a small quantity of soil. The lower end of the plant is held securely by a clamp. In order to subject the plant to the action of gases and vapours, or to variation of temperature it is enclosed in a glass cylinder (V) with an inlet and an outlet pipe (Fig. 58). The chamber is maintained in a humid condition by means of a sponge soaked in water. Different gases, warm or cold water vapours, may thus be introduced into the plant chamber.

Any quick growing organ of a plant will be found suitable for experiment. In order to avoid all possible disturbing action of circumnutation, it is preferable to employ either radial organs, such as flower peduncles and buds of certain flowers, or the limp leaves of various species of grasses, and the pistils of flowers. It is also advisable to select specimens in which the growth is uniform. I append a representative list of various specimens in which, under favourable conditions of season and temperature, the rates of growth may be as high as those given below:—

Peduncle of Zephyranthes |

0.700.7 mm. per hour. |

Leaf of grass |

0.701.10 mm.„ per„ hour.„ |

Pistil of Hibiscus flower |

0.701.20 mm.„ per„ hour.„ |

Seedling of wheat |

0.701.60 mm.„ per„ hour.„ |

Flower bud of Crinum |

0.702.20 mm.„ per„ hour.„ |

Seedling of Scirpus Kysoor |

0.703.00 mm.„ per„ hour.„ |

The specimen employed for experiment may be an intact plant, rooted in a flower pot. It is, however, more convenient to employ cut specimens, the exposed end being wrapped in moist cloth. The shock-effect of section passes off after several hours, and the isolated organ renews its growth in a normal manner. Among various specimens I find S. Kysoor to be very suitable for experiments on growth. The leaves are much stronger than those of wheat and different grasses, and can bear a considerable amount of pull without harm. Its rate of growth under favourable condition of season is considerable. Some specimens were found to have grown more than 8 cm. in the course of twenty-four hours, or more than 3 mm. per hour. This was during the rainy season in the month of August. But a month later the rate of growth fell to about 1 mm. per hour.

I shall now proceed to describe certain typical experiments which will show: (1) the extreme sensibility of the Crescograph; (2) its wide applicability in different investigations; and (3) its capability in determining with great precision the time-relations of responsive changes in the rate of growth. In describing these typical cases, I shall give detailed account of the experimental methods employed, and thus avoid repetition in accounts of subsequent experiments.

Determination of the absolute rate of growth: Experiment 51.—For the determination of the absolute rate, I shall interpret the results of a record of growth obtained with a vigorous specimen S. Kysoor on a stationary plate. The oscillation frequency of the plate was once in a second, and the magnification employed was ten thousand times. The magnified growth movement was so rapid that the record consists of a series of short dashes instead of dots (Fig. 59A). For securing regularity in the rate of

Fig. 59.—Crescographic records: (A) successive records of growth at intervals of one second (magnification 10,000 times). (ɑ) Effect of temperature on a stationary plate; N, normal rate of growth; C, retarded rate under cold; H, enhanced rate under warmth: (b) record on moving plate, where diminished slope of curve denotes retarded rate under cold. (Magnification 2,000 times.)

growth, it is advisable that the plant should be kept in uniform darkness or in uniformly diffused light. So sensitive is the recorder that it shows a change of growth-rate due to the slight increase of illumination by the opening of an additional window. One-sided light, moreover, gives rise to disturbing phototropic curvature. With the precautions described the growth-rate in vigorous specimens is found to be very uniform.

After the completion of the first vertical series, the recording plate was moved 1 cm. to the left; the tip of the recorder was brought once more to the top by the micrometer screw, S, (Fig. 58), and the record taken once more after an interval of 15 minutes. The magnified growth for 4 seconds is 38 mm. in the first record; it is precisely the same in the record taken fifteen minutes after. The successive growth elongations at intervals of 1 second is practically the same throughout, being 9.5 mm. This uniformity in the spacings demonstrates not only the regularity of growth under constant conditions, but also the precision of the apparatus. It also shows that by keeping the external condition constant, the normal growth-rate could be maintained uniform for at least fifteen minutes. The magnified rate of growth is nearly 1 cm. per second, and since it is quite easy to measure 0.5 mm., the Crescograph enables us to magnify and record a length of 0.0005 mm., that is to say, the sixteenth part of a wave of red light. The absolute rate of growth, moreover, can be determined in a period as short as 0.05 of a second. These facts will give some idea of the great possibilities of the Crescograph for future investigations.

As the period of experiment is very greatly shortened by the method of high magnification, I shall, in the determination of the absolute rate of growth, adopt a second as the unit of time, and μ, or micron, as the unit of length,—the micron, being a millionth part of a metre or a thousandth part of a millimeter.

If m be the magnifying power of the compound lever and l, the average distance between successive dots in mm. at intervals of t seconds then:—

the rate of growth = l/mt × 103μ per second.

In the record given l = 9.5 mm.

In the record given lm = 10,000.

In the record given lt = 1 second.

Hence the rate of growth = 9.5/10,000 × 103μ per sec.

Hence the rate of growth == 0.95μ per sec.

Having demonstrated the extreme sensitiveness and reliability of the apparatus, in quantitative determination, I shall next proceed to show its wide applicability for various researches relating to the influence of external agencies in modification of growth. For this two different methods are employed. In the first of these methods, the records are taken on a stationary plate: of these the record is at first taken under normal condition, the subsequent series being obtained under the given changed condition; the increase or diminution of intervals between successive dots, in the two series, at once demonstrates the stimulating or depressing nature of the changed condition.

In the second method, the record is taken on a plate moving at an uniform rate by clockwork. A curve is thus obtained, the ordinate representing growth elongation and the abscissa the time. The increment of length divided by the increment of time gives the absolute rate of growth at any part of the curve. As long as the growth is uniform, so long the slope of the curve remains constant. If a stimulating agency enhances the rate of growth, there is an immediate upward flexure in the curve; a depressing agent, on the other hand, lessens the slope of the curve.

I shall now give a few typical examples of the employment of the Crescograph for investigations on growth: the first example I shall take is the demonstration of the influence of variation of temperature.

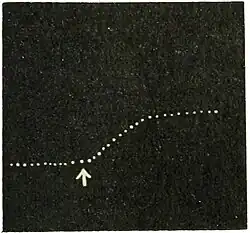

Stationary method: Experiment 52.—The records, given in Fig. 59ɑ, were taken on a stationary plate. The specimen was S. Kysoor; the Crescographic magnification was two thousand times, and the successive dots at intervals of 5 seconds. The middle series, N, was at the temperature of the room. The next, C, was obtained with the temperature lowered by a few degrees. Finally H was taken when the plant-chamber was warmed. It will be seen how under cooling the spaces between successive dots have become shortened, showing the diminished rate of growth. Warming, on the other hand, caused a widening of intervals between successive dots, thus demonstrating an enhancement of the rate of growth.

Calculating from the data obtained from the figure we find:—

The absolute value of the normal rate |

0.457μ per second. |

Diminished rate under cold |

0.101μ per„ second.„ |

Enhanced rate under warmth |

0.737μ per„ second.„ |

Moving plate method: Experiment 54.—This was carried out with a different specimen of S. Kysoor, the record being taken on a moving plate (Fig. 59b). The first part of the curve here represents the normal rate of growth. The plant was then subjected to moderate cooling, the subsequent curve with its diminished slope denotes the depression of growth. The question of influence of temperature will be treated in a subsequent Paper of the present series in much greater detail.

Precaution against physical disturbance: Experiment 54 There may be some misgiving about the employment of such high magnification: it may be thought that the accuracy of the record might be vitiated by physical disturbance, such as vibration. In physical experimentation far greater difficulties have, however, been overcome, and the problem of securing freedom from vibration is not at all formidable. The whole apparatus need only be placed on a heavy bracket screwed on the wall to ensure against mechnical disturbance. The extent to which this has been realized will be found from the inspection of the first part of the record in figure 60, taken on a moving plate. A thin dead twig was substituted for the growing plant, and the perfectly horizontal record not only demonstrated the absence of growth movement but also of all disturbance. There is an element of physical change, against which precautions have to be taken in experiments on variation of the rate of growth at different temperatures. In order to determine its character and extent, a record was taken with the dead twig, of the effect of raising the temperature of the plant-chamber through ten degrees. The record (Fig. 60) with a magnification of two thousand times shows that there is an expansion during

Fig. 60.—Horizontal record shows absence of growth in a dead branch; physical expansion on application of warmth at arrow followed by horizontal record on attainment of steady temperature. (Magnification 2,000 times.) the rise of temperature, and that the variable period lasted for a minute, after which there was a cessation of physical movement, the record becoming once more horizontal. The obvious precautions to be taken in such a case, is to wait for several minutes for the attainment of steady temperature. The movement caused by physical change abates in a short time whereas the change of rate of growth brought about by physiological reaction is persistent.

DETERMINATION OF LATENT PERIOD AND TIME-RELATIONS OF RESPONSE.

Experiment 55.—In the determination of time-relations of responsive change in growth under external stimulus, I shall take the typical case of the effect of electric shock from a secondary coil of one second's duration. Two electrodes were applied, one above and the other below the growing region of a bud of Crinum. The record was taken on a moving plate, the magnification employed being two thousand times, and successive dots made at intervals of two seconds. It was a matter of surprise to me to find that the growth of the plant was affected by an intensity of stimulus far below the limit of our own perception. As regards the relative sensitiveness of plant and animal, some of my experiments show that the leaf of Mimosa pudica in a favourable condition responds to an electric stimulus which is one-tenth the minimum intensity that causes perception in a human being. For convenience I shall designate the intensity of electric shock that is barely perceptible to us as the unit shock. When an intensity of 0.25 unit was applied to the growing organ, it responded to it by a retardation of growth. Inspection of Fig. 61 shows

Fig. 61.—Time-relations of response of growing organ to electric stimulus of increasing intensities applied at the short horizontal lines. Successive dots at intervals of 2 seconds. that there is a flexure induced in the curve in response to stimulus, the flattening of the curve denoting retardation of growth. The latent period, in this case, is 6 seconds. The normal rate was restored after 5 minutes. The intensity of shock was next raised from 0.25 unit to one unit. The second record shows that the latent period is reduced to 4 seconds, and a relatively greater retardation of growth was induced by the action of the stronger stimulus. The recovery of the normal rate was effected after the longer period of 10 minutes. I took one more record, the intensity being three units. The latent period was now reduced to 1 second, and the induced retardation was so great as to effect a temporary arrest of growth.

TABLE X.—TIME-RELATIONS OF RESPONSIVE GROWTH-VARIATION UNDER ELECTRIC SHOCK (Crinum).

| Intensity of stimulus. |

Latent period. | Normal rate. | Retarded rate. |

| 0.25 unit. 0.251 unit.„ 0.253 unit.„ |

6 seconds. 4 seconds.„ 1 seconds.„ |

0.62 μ per sec. 0.62 μ per„ 0.62 μ per„ |

0.49 μ per sec. 0.25 μ per„ Temporary arrest of growth. |

It is thus found that growth in plants is affected by an intensity of stimulus which is below human perception; that with increasing stimulus the latent period is diminished and the period of recovery increased; and that the induced retardation of growth increases continuously with the stimulus till at a critical intensity there is a temporary arrest of growth. I shall speak later of the effect induced by stimulus above this critical point.

Experiment 56.—As a further example of the capability of the Crescograph, I shall give the record of a single pulse of growth obtained with the peduncle of Zephyranthes Sulphurea (Fig. 62). The magnification employed was 10,000 times,

Fig. 62.—Record of a single growth-pulse of Zephyanthes. (Magnification 10,000 times.) the successive dots being at intervals of one second. It will be seen that the growth pulse commences with a sudden elongation, the maximum rate being 0.4 μ per sec. The pulse exhausts itself in 15 seconds, after which there is a partial recovery in the course of 13 seconds. The period of the complete pulse is 28 seconds. The resultant growth in each pulse is therefore the difference between elongation and recovery. Had a very highly magnifying arrangement not been used, the resulting rate would have appeared continuous. In other specimens, owing probably to greater frequency of pulsation and co-operation of numerous elements in growth, the rate appears to be practically uniform.

Advantages of the Crescograph.—There is no existing method which enables us to detect and measure such infinitesimal movements and their time-relations. The only attempt made in measuring minute growth has been by observing the movement of a mark on a growing plant through a microscope. The magnification available in practice is about 250 times. The observation of the movement would itself be sufficiently fatiguing. But a simultaneous estimate of the time-relations of rapidly fluctuating changes would prove so bewildering, that accurate results from this method would be altogether impossible. A 1/12″ objective gives a linear enlargement of about 1,200 times. But the employment of this objective is impracticable in the measurement of growth elongation of an ordinary plant. With the Crescograph, on the other hand, we obtain a magnification which far surpasses the highest powers of a microscope, and it can be used for all plants. It does not merely detect growth but automatically records the rate of growth and its slightest fluctuation. The extreme shortness of time required for an experiment renders the study of the influence of a single factor at a time possible, the other conditions being kept constant. The Crescograph thus opens out a very extensive field of inquiry into the physiology of growth; and the discovery of several important phenomena mentioned in this Paper is to be ascribed to the extreme sensitiveness of the apparatus, and the accuracy of the method employed.

MAGNETIC AMPLIFICATION.

The magnification obtained with two levers was, as stated before, 10,000 times. It may be thought that further magnification is possible by a compound system of three levers. There is, however, a limit to the number of levers that may be employed with advantage, for the slight overweight of the last lever becomes multiplied and exerts very great tension on the plant, which interferes with the normal rate of its growth. The friction at the bearings also becomes added up by an increase in the number of levers, and this interferes with the uniformity of the movement of the last recording lever. For securing further magnification, additional material contact has, therefore, to be abandoned. I have recently been successful in devising an ideal method of magnification without contact. The movement of the lever of the Crescograph upsets a very delicately balanced magnetic system. The indicator is a reflected spot of light from a mirror carried by the deflected magnet. Taking a single lever with the lengths of two arms 125 mm. and 2.5 mm. respectively we obtain a magnification of 50 times. The magnetic system gives a further magnification of 20,000 the total magnification being thus a million times. This was verified by moving by means of a micrometer screw the short arm of the lever through 0.005 mm. The resulting deflection of the spot of light at a distance of 4 metres was found to be 5,000 mm., or a million times the movement of the short arm. It is not difficult to produce a further magnification of 50 times by attaching a second lever to the first. The total magnification would in this case be 50 million times.

A concrete idea of this will be obtained when we realise that by the Magnetic Crescograph a magnification can be obtained which is about 50,000 times greater than that produced by the highest power of a microscope. This order of magnification would lengthen a wave of sodium light to about 3,000 cm. I am not aware of any existing method by which it is possible to secure an amplification of this order of magnitude. The application of this will undoubtedly be of great help in many physical investigations, some of which I hope to complete in the near future.

Such an enormous magnification cannot be employed in ordinary investigations on growth, for the moving spot of light indicating rate of growth, passes like a flash across the screen. But it is of signal service in my investigations on growth by the Method of Balance, to be described in a future Paper. The principle of this method consists in making the spot of light, which is moving in response to growth, stationary, by subjecting the plant to a compensating movement downwards. The slightest variation caused by an external agent would make the spot of light move either to the right or to the left, according to the stimulating or depressing character of the agent. It will be understood, how extremely sensitive this method is for detection of the most minute variation in the normal rate of growth.

THE DEMONSTRATION CRESCOGRAPH.

Before proceeding with accounts of further investigations, I shall describe a form of Magnetic Crescograph with which I have been able to give before a large audience demonstration of a striking character on various phenomena of growth. The magnification obtained was so great that I had to take some trouble in reducing it. This was accomplished by the employment of a single, instead of a compound system of two levers. The reflected spot of light was thrown on a screen placed at a distance of 4 metres, and this gave a magnification of a million times; it is obvious that an increase of the distance of the screen to 8 metres would have given a magnification of 2 million times. As it was, even the lower magnification was far too great for use with quick growing plants like Kysoor. I, therefore, employed the slower growing flower bud of Crinum. It will be seen from Table X that the normal rate of growth of the lily is of the order of 0.0006 mm. per second. The normal excursion of the spot of light reflected from the Crescograph exhibiting growth was found to be 3 metres in five seconds, or 60 cm. per second. This is a million times the actual rate of growth of the Crinum bud. As it is easy to measure 5 mm. in the scale, it will be seen that with the Demonstration Crescograph it is possible to detect the growth of a plant for a period shorter than a hundredth part of a second.

Experiment 57.—A scale 3 metres long divided into cm. is placed against the screen. A metronome beating half seconds is started at the moment when the spot of light transits across the zero division; the number of heats is counted till the index traverses the 300 cm. At the normal temperature of the room (30 C.), the index traversed 300 cm. in five seconds. The plant chamber was next cooled to 26°C. by the blowing in of cooled water vapour; the time taken by the spot of light to traverse the scale was now 20 seconds, i.e., the growth-rate was depressed to a fourth. Under continuous lowering of temperature the growth-rate became slowed down till at 21°C. there was an arrest of growth. Warm vapour was next introduced, gradually raising the temperature of the chamber to 35°C. The spot of light now rushed across the scale in a second and a half, i.e., the growth was enhanced to more than three times the normal rate. The entire series of the above experiments, on the effect of temperature on growth, was thus completed in the course of 15 minutes.

SUMMARY.

A description is given of the High Magnification Crescograph, which enables an automatic record of growth magnified ten thousand times. The absolute rate of growth can be easily determined from the data given in the record.

A magnification of a million times is obtained by the employment of Magnetic amplification. An increment of growth so minute as a millionth part of a mm. or 0.00000004 inch may thus be detected. It is also possible to detect the growth of a plant for a period shorter than a hundredth part of a second.

The influence of external conditions on variation of rate of growth is obtained by two methods of record. In STATIONARY METHOD, the increase or diminution of the distance between successive dots representing magnified rate of growth, demonstrates the stimulating or depressing nature of the changed condition.

In the second, or MOVING PLATE METHOD, a curve is obtained, the ordinate representing growth elongation, and the abscissa, time. A stimulating agent causes an upward flexure of the normal curve; a depressing agent, on the other hand, lessens the slope of the curve.

The action of external stimulus induces a variation of the rate of growth, the time relations of which are found from the automatic record of the growth. The latent period is shortened with the intensity of the stimulus. A responsive variation of growth is induced by an intensity of stimulus which is below human perception.

It is often possible to obtain record of the pulsatory nature of growth-elongation. Thus with the growing peduncle of Zerhyranthes, the growth pulse commences with a sudden elongation, the maximum rate being 0.0004 mm. per second. The pulse exhausts itself in 15 seconds, after which there is a partial recovery in course of 13 seconds, the period of complete pulse being 28 seconds. The resultant growth in each pulse is the difference between elongation and recovery.

The Magnetic Crescograph enables demonstration of principal phenomena of growth and its variation before a large audience.