Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 9

Mountain Spirits, Earth Spirits and other Spirits.

The Eskimos believe that they are surrounded on all sides by spirits, the same spirits which the angákut enlist in their service as helping spirits, and answering spirits. Distinction may be made between two different kinds of spirits, the more tangible, earth-bound spirits which in many ways correspond to those appearing in the folk-lore of other peoples as trolls and gnomes; and on the other hand, the personifications of such dissimilar things as fire, stone, a precipice, a feasting house or such like; these spirits are then referred to as the inua, the owner or lord, of the stone or house.

iʲᴇraq, plural iʲᴇrqät, corresponds to the isᴇrᴀq of Greenland. The word means literally: "those who have something about the eyes", and the name refers to the fact that the eyes of these mountain trolls are set lengthwise in the face, not transversely as ours are; they "blink sideways" with their eyes. The mouth is placed in a similar way to the eyes. They live up in the hills, or rather, inside the hills, which they have fitted up like great stone houses, much resembling those inhabited by white men. The shamans often see them disappearing into the cracks and fissures of rock that form their dwellings. They are not visible to human beings having no special relations with the supernatural, but only to shamans. Ordinary people are very much afraid of them, and hear only their whistling in the air; one must never show fright in any way, for they only attack the timid and cowardly.

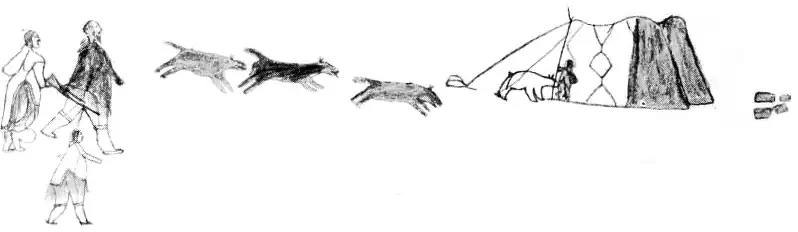

The iʲᴇrqät are famous especially for their running powers, and there is no animal which they cannot outrun. Caribou in full flight, for instance, they can overtake with ease. When, now and again, they capture a human being, the first thing they do is to make the captive a swift runner also. It is said that they have a method of cleansing the feet and shins of human beings through the action of worms in the earth or tiny creatures in the lakes. When these have eaten away the flesh from shinbones or toes, human beings become as lightfooted as the iʲᴇrqät. They are of the same shape as human beings, and live in the same way. The men are dressed in human fashion, only the women's garments are otherwise, their breeches consisting of the white skin from the belly of the caribou; white belly skins all cut up into strips. They are as strong as wolves; when they have killed a caribou, they run home with it, slinging it over their shoulders just as a wolf does with its prey. They have always a great store of all manner of delicacies in the way of food, especially fat and suet from the caribou, which they boil down and leave to set in great skin bags made from the hides of bull caribou. When they capture human beings, they keep them, and do not allow them to go away again. Shamans have found among them strange implements very much like the mirrors used by white men. This implement is at once a mirror and a spyglass. It glitters like mica, and when one looks down into it, all that is passing far away among the dwellings of men is reflected in this mirror; therefore the iʲᴇrqät know all about mankind.

Aua's father, Qingailisaq, called Oqâmineq: "the man with the sharp tongue", gave the following account of his encounter with the iʲᴇrqät: it is here reproduced according to Aua's version:

"My father was out once hunting caribou, and had killed four. He was just cutting them up when he saw four men coming towards him. They came over the crest of a hill, and he thought at first it was caribou. But they came closer, and he saw that they were iʲᴇrqät, two men with their grown-up sons. One of the sons was quite a young man. All were big men, and they looked just like ordinary human beings, save that they had nostrils like those of the caribou. The oldest of the men seemed very excited, he at once grasped hold of Oqâmineq, pressed his hands against his chest to throw him down, but Oqâmineq remained calmly standing, and the angry iʲᴇrᴀq could not do anything with him.

Then said the iʲᴇrᴀq: "Will you do any harm?"

"I will do no harm; you need not be afraid of me" answered Oqâmineq.

Then the iʲᴇrᴀq at once loosed hold of him, and proposed that they should sit down on a stone and talk. And he told his son to cut up the caribou my father had been cutting up himself. The work was speedily done, though he had no knife; he flayed them in the same way as one does a lemming, simply tearing open the skin, but it was done more rapidly than by a man working with a knife.

The iʲᴇrᴀq sat down on a stone and talked with my father. He said they lived in the country inland from Piling, near Nuvuk; they lived by hunting caribou. They had a small pocket in their tunics, in which they kept two small stones. They were mighty runners, and could outrun the caribou; when they came up quite close, they killed them with the stones in their pockets.

The old iʲᴇrᴀq was out looking for a son that was lost — a son who had not come home from his hunting, and he now thought he must have been killed by human beings, and had at first believed that it was Oqâmineq who had killed him. But Oqâmineq said he had never seen an iʲᴇrᴀq before, and the other then grew calm, and they parted in friendship and mutual understanding.

My father, who was a great shaman, went home and had a dress made like that of the iʲᴇrᴀq, but with a picture of the hands in front, on the chest, to show how the iʲᴇrᴀq had attacked him. It took several women to make that garment, and many caribou skins were used. There were a number of white patterns in the dress, and it became a famous dress, which was bought by him who was called: anak'oq (the well known whaler and collector for the American Museum of Natural History, Capt. George Comer), and my father was paid a high price for the garment, which is the only iʲᴇrᴀq tunic ever made by human hands.

A few of the best known stories of iʲᴇrqät are here given.

Two women who were out gathering fuel (Cassiope), were stolen away by the iʲᴇrqät. They stayed among them, and one of the girls had a child. It was feared that they might run away, and they were therefore always guarded. One day they were taken to a warm lake where it was the custom to remove the hair from caribou skins. They were made to stand with their feet in the warm water, and the big toe was then opened and some of the flesh cut away. Part of the skin and flesh of the big toe were cut away, and it was said that it was this which prevented human beings from running swiftly.

The two girls at last grew weary of living among the iʲᴇrqät, and went away, pretending they were going out to gather fuel, but as usual, there was one to keep watch over them. They managed nevertheless to hide in a fissure of rock near a river. One of the women had her child on her back. The other woman had no children.

It was at once discovered that they had run away, and a search was made at once, and dogs taken out.

When the iʲᴇrqät came to the river and had to cross it, they leapt across, and that with such speed that one only heard the wind of their flight.

A dog found the women, but they said to it:

"We will kill you if you say anything".

The dog promised not to say anything, and simply went off after the others who were searching. It was afraid of being killed. The child on the woman's back tried to call to its father, but one of the women then took it by the throat and strangled it. The iʲᴇrqät searched until evening then they went home.

The girls continued their flight and came to some human beings who were very fond of athletic sports. They took part in the sports, but without letting the others notice how swift they were; only when playing ball did they take rather more trouble. One day someone said to them:

"We have heard that people who have been stolen away by the iʲᴇrqät become good runners".

The two girls would never show how good they were at running. They always said they could only run quite slowly, but once, when they were out playing ball, one of the girls threw the ball to her companion, and they began running.

One of the girls said:

"Run like a young caribou."

The other girl said:

"Try to run like a young cow with calf."

And then they ran. And the dust rose up behind them at every stride. They ran a long way, but came back again, and all the lookers-on stood staring.

"That is the way you should run when playing ball" said the two girls, and gave the ball to the others, but no one wanted to play ball any more, and all went home.

The two girls stayed on afterwards at that village and were married, and they were never again invited to take part in any kind of sport or ball game; they were left to themselves. But when they went out to gather fuel, they often came home with caribou. And their husbands loved them, because, though they were women, they brought meat to the house.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

There were once two old men who had nothing to live on. Not knowing what to do, they decided to seek refuge among the iʲᴇrqät, for they had heard that one had only to cross a great river and follow it up, and would then come to the land of the iʲᴇrqät.

So they left their own place, and walked and walked, and kept on walking until they came to a stream, and this they followed up inland. They passed a caribou lying dead on the ground, but they simply passed it by, and walked and walked and kept on walking.

On the way they saw more slain caribou, floating down the stream. Once, when there was a big fat bull among them, they hauled it ashore, cut it up and ate of it. After that they made up great loads of meat and carried these with them farther up inland.

Suddenly they were surrounded by iʲᴇrqät, who called out to them that they were not to drag any more of the caribou carcases ashore. They looked round, and perceived many tents, and they were invited to come in as visitors; they went in, and were given sleeping rugs and shown their places. A tent was also given them, and they now lived here. They were given the most delicious rich tongues, and tender steaks, and every day fresh skins were given them for sleeping rugs and coverings. The iʲᴇrqät were skilful hunters, and withal good and kindly folk, and the two old men stayed with them and lived in abundance to the end of their days.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

iɳnᴇriugjᴀq, plural iɳnᴇriugjät, corresponds to the Greenland form iɳnᴇrʃuᴀq, plural iɳnᴇrʃuit, and means literally: "the great fire". The name refers to the fact that the windows of the sea spirits, or perhaps more correctly the shore spirits, are sometimes seen lighted up. The spirits of earth, on the other hand, have luminous lard bladders in their huts and take their name from this.

The iɳnᴇriugjät, the sea or shore spirits, always have their houses on small reefs or rocky islets; they are exactly like human beings to look at, and not here, as in the Greenland stories, without noses. Some indeed say that they have very handsome noses; others again that their nostrils are like those of the caribou. All their clothes are made of sealskin. They never wear clothes of caribou skin, as the Eskimos in the neighbourhood of Hudson Bay otherwise do: they live on, and utilise exclusively, the animals of the sea. They are visited only by shamans, who state that they have warm and comfortable houses. They are not hostile to man, but on the contrary, often endeavour to help those who cannot get along by themselves, as they are very skilful hunters. The shamans often employ them as helping spirits. When the supply of meat runs out, the shamans often visit them and bring home meat from there. When game becomes scarce, the shaman will often visit their dwellings, which are just below the surface of the sea under the rocks where they live. From here they often send newly killed seal up to the surface as gifts to mankind. The only instance, as far as Aua's knowledge went, of harm done to human beings by the sea spirits was the following:

There was once a man who was left alone on the hunting grounds out on the ice, after all his companions had gone home. A seal came up to breathe at the blowhole where he was waiting, but when he harpooned it, both seal and harpoon disappeared in some way he could not understand. He then went homewards, and on the way, came to a house he had not seen before. He went inside, and was kindly received, and boiled meat was set before him that he might eat. An old woman asked him: "Do you like meat soup with blood in?"

The man answered: "If it is meat soup, I should be the last to despise it."

He drank the meat soup, stayed a little longer with the strangers, and then went home. He went homewards, and arrived at the place. But he had not been home long before he began to feel violent pains in his stomach, and then a remarkable thing happened, in that a harpoon suddenly appeared in his body, having passed through it from one side to the other. And the moment this took place, the man fell down dead. A shaman then explained that it was the iɳnᴇriugjät who had stolen his harpoon when he harpooned the seal, in order to kill him afterwards with his own weapon. The sea spirit had uttered a spell over the harpoon, changed it into seal meat, and this led him to swallow it, in order that it might bore its way out through his body after he got home, and kill him.

The iɳnᴇriugjät of earth lived far up inland, and hunted only caribou. They were mighty hunters, and had always abundance of meat and fine caribou skins. People who have visited them say that along the walls inside the houses were small shining things; they could not understand what they were, but they looked like intestines filled with suet and entrails, and resembled both intestines of caribou calves and of fully grown beasts. If only one could get hold of one of these mysterious luminous things, which they had no name for, one would become a very great shaman, provided one carried the light on one's person for the rest of one's life. This then became the shaman's aɳak·ua or qaumanᴇq. These luminous, transparent and oblong bags that shone out from the side walls of the house, have given those spirits the name of iɳnᴇriugjät. They too resembled human beings, but at the same time, their eyes and mouth were like those of the iʲerqät. They had very narrow faces and long noses.

A young man who was out hunting caribou once came to the land of the iɳnᴇriugjät. He entered a large and comfortable house, but hardly had he got inside before he was forbidden to go out again. These fire spirits never slept, they were always awake, they did not understand how to sleep. The young hunter, who had walked far and was now tired, soon began to feel sleepy, and as he had been awake for a long, time, he made ready to sleep on the spirits' bench, but every time he lay down and closed his eyes, the iɳnᴇriugjät cried: "he is dying, he is dying!" and raised him up and woke him.

At last the man was tired and sleepy beyond endurance, and said: "You must not raise me up because I lie down and close my eyes. I am not dying, I am only going to sleep."

But the spirits, who did not know what sleep was, raised him up every time he tried to sleep, and the man, who was never allowed to sleep, at last grew ill with exhaustion and died.

Since then, only very great shamans have dared to visit the iɳnᴇriugjät, for though they are not otherwise hostile to men, there is this dangerous thing about them, that they cannot endure to see a human being sleep.

tᴀrqajägʒuᴀq, plural tᴀrqajägʒuit, the Shadow Folk, are quite like ordinary human beings, but there is this peculiar thing about them: that one never sees the beings themselves, only their shadows; they are not dangerous, but always good to human beings, and the shamans are very glad to make use of them as helping spirits. They hunt by running, and can only bring down an animal if they are able to overtake it on foot. These Shadow Folk correspond to the tᴀʀajaⁱt of the Greenlanders, and Ivaluardjuk related of them as follows:

"It is said that there is this remarkable thing about the Shadow Folk, that one can never catch sight of them, by looking straight at them. The Shadow Folk once had land near Tununeq (Ponds Inlet). One day, an elderly man appeared among them and stayed with them. And the Shadow Folk came and brought food both for him and his dogs. The Shadow Folk themselves had also dogs: one of them was named Sorpâq.

"One day, the Shadow Folk spoke to the old man who was visiting them as follows: 'If you should ever be in fear of Indians, just call Sorpâq. There is nothing on earth it is afraid of.'

"The man remained for some time among the Shadow Folk, and then went home again. He came home, and some time after he had come home, his village was attacked by Indians, and the old man then fell to calling Sorpâq. Sorpâq at once appeared, and began to pursue the Indians. Every time Sorpâq overtook an Indian, it bit him and threw him to the ground, killing him on the spot. Thus Sorpâq saved all the people of the village, who would otherwise have been exterminated by the Indians.

"It is said that these Shadow Folk are just like ordinary human beings, save that one cannot see them; otherwise, they have the same kind of houses and the same kind of weapons, harpoons and bladder harpoons, just like everyone else."

Told by

Ivaluardjuk.

kukiliga·ciait is the plural form of kukiliga·ciᴀq and means: "those with the great claws", corresponding to the Greenlanders' kukiʃ·a·jɔ·q, plural kukiʃ·a·jo·t.

The Claw-Trolls live far up inland, where in winter they dwell in snow huts, just in the same way as human beings do. They are very dangerous on account of their long claws. If they come upon human beings, or human beings come to them, they will attack with their long claws, and keep on scratching and tearing at them all over the body as long as there is any flesh left. Only the greatest of shamans ever escape alive from such an encounter.

These Claw-Trolls are best known in the stories from their encounter with the Moon and his sister the Sun, when the pair were wandering out into the world after having killed their wicked grandmother. The story is given elsewhere. Only very bold and skilful shamans dare to have a kukiliga·ciᴀq for a helping spirit; but the shaman who does so venture is held in high esteem and feared by all.

The amajɔrʒuk is an ogress, hated and feared beyond all the other earth spirits. The naughtiest children can be made to stop crying at the mere mention of her name. She is said to be great ogress, with a big amaut on her back; it is made of untanned hide of great male walrus; it is filled with old rotten seawed, and the human beings whom she captures smell of seaweed long after, even when they escape without delay.

The amarjɔrʒuk attacks both adults and children, and as soon as she has overtaken her victim, she puts it down into her amaut, from which none can escape without aid. She is the most feared of all soulstealers, and only the greatest shamans dare to set out against her.

amajɔrʒuk was one of Aua's helping spirits.

amajɔrʒuk corresponds to the Greenland amᴀrsiniɔ·q.

inɔrᴀrutligᴀ·rʒuk, plural inɔrᴀrutligᴀ·rʒuit, answer to the Greenlanders' inuᴀruL·igᴀq, plural inuᴀruL·ik·at, meaning literally: "the Little People, the Dwarfs".

It is said that the inɔrᴀrutligᴀ·rʒuit live in the mountains just in the same way as human beings, and are just like them to look at, but quite small. They are no bigger than the lumbar vertebra of a walrus set on end. Their clothes are made of caribou skin, often cut to the same pattern as those of human beings. They are as a rule mischievous and hostile. When they meet a human being, they suddenly grow, and as soon as they have grown as tall as their opponent, they fall upon him and throw him down, if they are strong enough; then they remain lying on the victim until the latter is starved to death. Should they on the other hand be overthrown themselves, they pretend to die, and the human being leaves them, believing them killed; but if one turns round a moment after leaving them, they have always disappeared without a trace. The inɔrᴀrutligᴀ·rʒuit kill their game by following up an animal's track and keeping on until they overtake the beast. If a human being has killed it meanwhile, they nevertheless consider it their own catch, and grow angry if the hunter refuses to give it up. They are very swift-footed, and can outrun every animal there is.

They are good and effective helping spirits, and much sought after as such.

Many different stories are told about them. Here is one of the bestknown:

inɔrᴀrutligᴀ·rʒuk, a little Mountain Dwarf, once came with his wife on a visit to a village where there lived none but an old woman and her granddaughter. They built their house close to that of the old woman, as a double house with a single entrance, and the old woman entertained her guests as well as she could, but the guests returned to their part of the house without having eaten their fill, and being, hungry after their journey, they took the after-part of a caribou and the tail fin of a whale in to thaw, and began eating of these.

inɔrᴀrutligᴀ·rʒuit made a long stay, and when the day came for them to leave, the old woman invited them to stay on, but in vain; they wished to go, and they went. The old woman wished to keep the hindquarters of the caribou bull and the tail fin of the whale, of which they had eaten, and so she spat on them, to make them freeze fast to the bench. The dwarf and his wife came in to fetch them, but as they could not get the meat loose from where it lay, they left it behind in the snow hut.

"It is impossible to get it loose, it is frozen fast" said the dwarf's wife.

"When a thing is impossible, one must leave it" answered her husband, and so they left the meat where it was. But after they were gone, the old woman and her granddaughter went in to fetch it, and lo! the hindquarters af the caribou bull had changed into that of a gull, and what had been the tail fin of a whale was now no more than the stump of a bird's tail.

The possessions of a dwarf, and his game, are always directly proportional to the size of the dwarf himself, but as long as they are being dealt with by one of the dwarf race, they appear to human beings as if they were real large animals, of the type they represent.

Some time after, other visitors came to the village. They heard the noise of dogs and the talking of human beings, but could see nothing but some shadows moving over the snow. They had received a visit from the tᴀrqajᴀ·qjuit.

Then they heard a voice, which came from the wife of the visiting tᴀrqajᴀ·qjuᴀq:

"We have come to the house of poor folk who appear to have nothing to eat. We will give them some meat".

And then the shadow folk built them a new house, and the old woman and her granddaughter moved in, and they brought meat into the new house, and said:

"Take this, though it is not very much. All the meat on our sledge is frozen".

The Shadow Folk were clever hunters, and the man caught seal, caribou and salmon, and the old woman and her grandchild lived in abundance.

One day there came other visitors again. This time it was a party of real human beings, and the Shadow Man wanted them to go out hunting with him. They went out together, and it often happened that the Shadow Man vanished from the sight of his companion, and they had to search for him. The man was ill at ease about having such a comrade while out hunting, and when he saw a shadow close beside him, he stabbed that shadow with a knife. He killed him, and the moment he was dead he became visible. He was a young and handsome man.

The Shadow Folk mourned deeply at his death, and went away, though the old woman and her granddaughter did all they could to make them stay, for they had grown very fond of them.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

Inukpäk, plural inukpait, means a giant, and answers to the Greenland term, which is the same.

It is said that the inukpait are fashioned just like ordinary human beings, save that they are mighty and huge, but otherwise harmless, and indeed well disposed towards mankind. So large are their bodies, that when a man of the human race marries an inukpäk woman and goes to lie with her, he is altogether lost in her genitals and dies. But if an inukpäk man lies with a human woman, it has happened that he has thrust his penis right through her and killed her. The following story is told wherever Eskimos are to be found, but in different versions. Right over in East Greenland men know this story of the giant who was treated with scorn because he had only two teeth.

There was once a giant who stood astride of a fjord, catching sea-scorpions. He was so big himself that he called the whales sea-scorpions.

A little mountain dwarf stood on the shore watching him. He cried:

"You giant, you great giant, your catch is a morsel for two teeth."

The giant did not answer. But the dwarf kept on calling out, and so at last the giant went up after him.

The dwarfs, inɔrᴀrugligᴀ·rʒuit, who are mountain spirits, have the faculty of growing to suit the size of the things they meet, and so it happened now; the little dwarf suddenly became big, when the giant fell upon him to thrash him. But the giant threw him down all the same, with such force that he lost one leg, and the giant left him lying there, and went back to the fjord where he was catching sea-scorpions.

One day when the giant was out, he swept up a whole umiaq with its crew in the hollow of his hand, and took them home. He lived on a shelf, a rocky shelf on a steep cliff. Thither he carried the umiᴀq and its crew, and whenever he wanted to sleep, he laid them on his cheek.

The people of the umiᴀq were soon weary of dwelling on the rocky shelf, and one day when the giant lay down to sleep, they bored at hole in his nose and lowered themselves down to the ground.

There were still two remaining when the giant woke, but those who had fled hid among the rocks.

"Where are my children?" asked the giant, when he awoke. Then one of those who had been left behind sang:

Your children let themselves down,

It is true, it is true.

Through a hole in your nose,

They let themselves down,

Ijaja, ijaja."

Then the giant began digging in the ground to make a new channel for a river, and the river then burst through the country and flooded it, carrying with it all those who had hidden among the rocks, so that they perished.

But the giant remained up on his rocky shelf with his human children, and whenever he lay down to sleep, he set them on his cheek so that they should not run away.

One evening when the giant lay dozing, the two men caught sight of a bear, a great he-bear. At first they did not know how to wake the giant, but then one of the men picked up a piece of rock and began hammering at the giant's head. It was no use, the giant would not wake up. So they took a bigger piece of rock and began hammering at his head with that. Then at last the giant woke, and they cried to him:

"There is a bear down there".

The giant got up and went to meet the bear, sticking one of the men in under his belt and the other in the lace of his kamik. On the way, the man under the belt was crushed and killed, and only the one in the lace was left alive.

The giant went up to the bear, took it in his fingers and killed it.

Whenever the giant ate, the man who was with him used to gather up great stores of meat from the crumbs that fell from his food. And now I know no more of that story.

Told by

Naukatjik.

Nᴀra·je· answers to the Greenland form nᴀraje·, and means properly: the one with the big belly. They are excellent helping spirits, as their enormous voracity renders them very swift. When a nᴀra·je· girds up his stomach, there is not a living creature that he cannot outrun. All else that is known of them is told in the following story:

A nᴀra·je· spirit once took a human being to live with it. One day they sighted some caribou. They went into hiding, so that the caribou could not see them, and here the nᴀra·je· spirit began girding up his belly with a long strip of hide. He had so huge a belly that it almost hung down to the ground. His adopted son was afraid he might burst if he tied himself up like that, and suggested that he himself should run after the caribou. But the nᴀra·je· spirit went in chase of them all the same, and though they had a long start, he ran so swiftly once he had fastened up his belly, that he overtook them all. Then he struck them one by one over the legs so that they could not walk, and then he killed them. He was a glutton, who could eat a whole caribou at once, and it was his custom, when about to feed, to make a hollow in the ground for his belly, and there he would lie down and begin to eat.

The nᴀra·je· spirit ate a whole caribou, and when the adopted sou came near, he was frightened, and cried:

"When I have eaten so much you must go a long way round and keep well away from me": "avu·nakan·ᴇq" (A long way round; keeping some distance off).

Here ends this story.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

There are spirits which take care that human beings shall not become too devoted to songs and festivals: they also dislike to hear children making too much noise out in the open or in the houses when alone without adults.

There was once a great village where the people were very fond of assembling for festivals in the dancing house. When the huts were deserted, the children were gathered together in a big house. In this house there was a very large drying frame, made of sealskin thongs tied together, and it was the children's custom to do gymnastic exercises in these, and not infrequently, one or another of them would get hurt: for they were only children, and had no one to look after them. When the children were not playing inside the house, they would run outside and scream and shout, or they would play at being shamans, and pretend to be calling up spirits.

Once when the grown ups were at a singing festival, the children played as usual, shouting and making a noise, and when the lamps, with no one to tend them, began to smoke, they ran outside. But here they suddenly discovered that the great Thrashing Spirit was coming towards them. Ahead of it ran its whip, which was a live bearded seal. The children, terrified, ran back to the house to hide. In the confusion, while all were trying to conceal themselves, there was a little boy who asked the others to lift him up on to the great drying frame of sealskin thongs, and the others lifted him up, and he hid away there. Some hid in the space under the bench, others crept into the side cupboards of the house where skins and furs were kept. The children had just hidden themselves when the Thrashing Spirit came in through the passage. In front of it crawled its whip, which was a live bearded seal. Once inside the house, the Thrashing Spirit picked up the bearded seal by its hind flippers, swung it like a whip and thrashed all the children to death. Only the little boy who had clambered up on to the drying frame remained undiscovered. Then the Thrashing Spirit went out of the house and disappeared.

All the grown ups had been in the dancing house, and stayed a long while at their singing. When at last they came home, they found all their children had been killed. The boy up on the drying frame climbed down and told who it was that had killed all the others. All the men at once set about preparations for vengeance, and made ready their weapons. Next day they again held a song festival in the house they used for dancing, just as if nothing had happened, but some of the men hid in the house where the children had been murdered. Now and again the men went out of the house to see if anyone was coming, and at last they saw the Thrashing Spirit approaching. One of the men then clambered up on to the great drying frame, taking with him a lamp and some oil which had been heated over the lamp. The oil was just thoroughly scalding hot when the Thrashing Spirit at last came into the house. In front of it crawled its whip, the live bearded seal. Hardly had the bearded seal entered the house, when the man up on the drying frame poured the boiling oil down over it. There was a fizzling sound, and at the same time, the other men, who had hidden themselves about the house, sprang out and stabbed it. The bearded seal died almost at once. But the Thrashing Spirit itself escaped out of the house, and though the men ran after it, none of them could overtake it.

But it is said that after that, the Thrashing Spirit never visited people who were singing in their feasting house, now that it had lost its whip.

Told by

Ivaluardjuk.

— — —

Some stories concerning various spirits are given in the following pages. They are set down without comment, as all that is known about the spirits in question is given in the stories themselves.

There was once a woman who saw two Indians come rowing across a lake, and she sat down to wait for them. When they reached her, they proposed that she should sit down in the back of their kayak, as one of the men had no wife, and would like to marry her; but the woman did not want to get married, she rejected the men and let the kayak row on. But as she turned her back upon them, she laid her hands on a big stone, and suddenly it was as if the stone began dragging her towards it. It was the Stone Spirit that took her, because she had rejected her fellow human beings, and when the stone drew her to it, she began to grow stiff, and as soon as she felt this, she cried out to the men in the kayak, at the top of her voice:

"Dear kayak men, come back, you may have me for your wife if you like."

But the men in the kayak rowed on, and again the woman cried out:

"Dear kayak men, come back, you may have me for your wife if you like. Now my feet are turning to stone, now my legs are turning to stone, now my body is turning to stone."

But the men in the kayak paid no heed to her cries, and so the Stone Spirit took the woman to itself, and she was turned into a pillar of stone.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

It happened that people disappeared, and no one knew how. It happened that children running about outside at their play were suddenly lost, or that caribou hunters up inland did not return. And then it is said that three children of the same parents were out one day playing together. The oldest carried the youngest in an amaut. One of them found a little bird carved out of walrus tusk, and at that they all fell to searching eagerly about in the hope of finding more, and so intent were they on their search, that suddenly, without knowing how, they found themselves in a house. The moment they got in, a woman came and placed herself in their way, so that they could not get out again.

The oldest girl understood that they had come to the house of a spirit which ate human beings, and so she said:

"Before we begin eating this tender calf I am carrying, just turn round and eat a little of the earth by the door opening; and close your eyes, and cover them with your hands, and howl at the top of your voice."

The girl had the jaw of a seal in her hand, and as the Spirit of the Precipice began eating away at the passage, she herself fell to digging in the ground with the jawbone. The girl had just managed to dig a hole through the ground when the Spirit of the Precipice was about to open her eyes, so she said:

"Do not open your eyes, eat a little more of the earth by the doorway; then you shall soon have the tender little calf to eat."

The Spirit of the Precipice closed her eyes again and fell to howling with all her might, and at the same moment the girl sent out her two little sisters, making them go first through the hole she had dug; then as she herself was about to follow them, the Spirit tried to grasp her, but only managed to get hold of a piece of her clothing, which she tore off and kept in her hand. Thus the girl got away. The Spirit of the Precipice called after her:

"Did you see all the heads lying about in here, all the human heads? When I have nothing to eat, I suck the snot from their noses."

The girl took her little sisters by the hand and they fled homewards as hard as they could. They had got a good way when the Spirit came out of her house and cried after them:

"I had not thought you could be so artful!"

When they got home, the children told what had happened, and thus it became known what had happened to all the children and all the caribou hunters that had disappeared. It was the Spirit of the Precipice that had taken them. None of the men were at home, so the women of the village all set about to take vengeance on the Spirit of the Precipice. One of the women took down a new sealskin thong, one that had never been used, and then they tried to do exactly as the children had done. They began looking about on the ground for small figures of birds carved out of walrus tusk. One of the women found such a figure, and before she knew where she was, she had been drawn into the house, and at once she spoke to the Spirit, and said:

"The whalers cannot kill the whales they catch, and therefore I have come to cut your claws."

At these words, the Spirit stretched out her hands, and said:

"You are right. My nails have got so long."

"Let me see your feet as well," said the woman. But as soon as the Spirit had stretched out hands and feet, she bound them with the sealskin thong and cried out to the others outside the house to pull. The Spirit tried to resist with her feet, but the women outside pulled so violently that one of the Spirit's hips was broken, and at last they pulled her out of the house. Then they dragged her away, hauling her along over the ground. They tried to pick out the most uneven parts, so it was no wonder the Spirit was soon on the point of death. Then suddenly it said:

"Wait a little before you kill me, wait a little. Let me tell you a little story first. My entrails are made of beads, wait a little, wait a little before you kill me. My liver is made of copper, wait a little, wait a little before you kill me. My lungs are made of a hard white stone, but I do not know what my heart is made of."

Hardly had the Spirit spoken of her heart when she breathed her last and died.

Then they cut up the dead body to see if what she had said was true, and sure enough: hardly had they slit up the belly when they saw that it was full of beads, and they took out the beads and made bracelets and necklaces of them, but there were many more than they could use, and they took the rest home.

They lay down to sleep, decked out in all their fine beads, but when they awoke next morning, all the beads had turned into ordinary human entrails.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

There was once a woman who could not get married, and so she married a spirit. The spirit could not eat the same food as the woman, and though she always invited him to partake of every meal, he wasted away and was at last nothing but skin and bone. One day he left the house and went out on to a great plain. He cut a hole in the ground in the same way as one cuts a hole in the ice of a lake, and began fishing. It was not long before he brought up a whole caribou, a fine big beast with plenty of suet. He took the caribou home with him, and they lived on that. He himself was able to eat of it. But when the caribou was all gone, the spirit went down to the sea and set about hunting seal. Here, however, he never caught anything, and again he wasted away; for he could not eat meat that others had caught. Once, when the hunters had been out, and the spirit as usual came home without having caught anything, he pulled out a piece of his own intestine and came home with it in his hand. His wife's parents, who thought he had made a catch, received him with pleasure, and made preparations to cook the piece of intestine, which they supposed was from a seal. They put it into the pot and began to boil it, but before long a horrible smell spread through the house. Then said the spirit:

"I think it must be cooked now." And he got up and took a step across the floor, but at the same moment he fell down dead.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

The story begins with a man who lived somewhere or other and had a real woman for a wife. The man was a great caribou hunter, who went out on long, long hunting expeditions, often remaining away for many days. One day he came home from his hunting, and as he approached his dwelling, he saw his wife wading out in a lake. He hid himself in order to see what she was about; and then he heard her say:

"Oh penis of the Lake Spirit, come up to the surface and show yourself."

At these words a great penis appeared in the middle of the lake and the woman went out to it and let it go up into her genitals. The man stood watching, then went home, but said nothing to his wife of what he had seen. On the next day he did not go out hunting, but went up to the lake. He placed himself by the edge of the water, and imitating his wife's voice, uttered the same words he had heard her say the day before; and sure enough, a penis at once rose up to the surface of the water, and the man waded out, cut it off and carried it home to his house. He then set to work to boil it. When it was done, he said to his wife:

"Here you are, eat."

The woman took the food her husband gave her and began to eat.

Then said her husband:

"What is that you are eating?"

"I do not know," answered his wife.

But then he said:

"It is your lover's penis."

"Then no wonder it tastes so nice," said the woman.

Then said her husband again:

"Which are you more afraid of: a knife, or maggots?"

"Maggots one can crush, but I am afraid of a knife," answered the woman.

After that the husband said nothing, but went out hunting as usual, only now he nearly always came home with one mitten. The other one he had lost, so he said. It was because he was collecting maggots in his mittens. When he had got together a great number of maggots, he brought them home, spread a skin on the floor and told his wife to undress and sit down on it.

The woman tried to keep her tunic on by clutching the tails between her thighs, but her husband cut away the ends of the stuff and pulled off the tunic, and then he poured all the maggots out over her. And the maggots crawled into the woman, in through her mouth, her nostrils and every opening of the body. Thus they came into her body and killed her.

This the husband did because his wife had the Spirit of the Lake for a lover.

Told by

Ivaluardjuk.

After that the man set out on a journey, and when he had come far from his own place, he put up a tent and settled down there and began hunting in those parts. He went out hunting caribou as usual, but now it happened that sometimes, on returning home to his tent, he would find cooked meat in the pot. When this happened several times, and he had found a meal ready waiting for him on his return, he determined to try to find out who it was that cooked his food for him. He pretended to go out hunting, but hid himself near the tent and kept watch.

He had not been waiting long when a little fox appeared and stole into the tent. Before going in, it took off its skin and laid it out to dry on the stones; and thus it turned into a young woman, and went into the tent. She only stayed in the tent a little while at a time, and kept coming out and looking round, in fear of being taken by surprise; but whenever the woman went into the tent, the man ran towards it as hard as he could: then as soon as she came out he hid again; when she went in, he ran a little way again, and in this manner he approached the tent. At last he was near enough to run up and snatch the fox skin just as she was coming out of the tent. The woman at once came up to him and begged and prayed him to give her back the skin, and when he would not, she burst into tears.

"I will marry you" said the man.

"No, I will not" answered the woman.

"You shall not have the skin unless promise to marry me".

"Well then you may have me for your wife, but now give me the skin".

Thus the man obtained a wife, and they lived together in his dwelling.

The summer passed, and the winter set in, and there came a raven in human form to visit them.

One day the raven said suddenly that he noticed a strange smell of urine in the house.

At these words the husband said:

"My wife feels uncomfortable when you say such things. Please never speak of it when she is within hearing".

This warning had no effect. The raven said again:

"How can it be there is such a strange smell of fox in here."

At these words the young wife burst into tears, drew forth her bag, and took out a fox skin and began chewing it to make it soft. As soon as the skin was soft enough, she put it on, and ran out into the passage and disappeared.

"Oh, oh, now I have made my dear host a widower" said the raven.

At these words the man said:

"Ugh, what is that horrible stink I can smell? It is like dog's dirt."

He said that because the raven's wife was a piece of dog's dirt in human form.

After that the man went outside to try to follow up his wife's tracks. He followed the tracks in the snow, there was one of a fox and one of a human being. Thus he came to a village. He went straight into the house and found his wife, who was in there. But every time he sat down beside his wife, she slipped away from him: so he spat on his first finger and touched her with that, and then she did not try to escape from him any more. And in that way he got back his wife again.

Told by

Ivaluardjuk.

There was once a family who had put their drying frame away in a feasting house, and so they sent a young girl in to fetch it. It was a dark evening, and when the girl came into the dark house, she said:

"Where is the spirit of the feasting house?"

"Here he is" answered the spirit, He was quite naked, and had no hair.

"Where are your eyes?" asked the woman.

"They are here," answered the spirit in a very deep voice and he spoke in a deep voice because he was not a human being, but a spirit.

"And where is your nose?"

"It is here!"

"And your ears?"

"They are here!"

"And your mouth?"

"It is here!"

"And your hands?"

"They are here!"

"And your feet?"

"They are here!"

"And your penis?"

"It is here?"

"And your testicles?"

"They are here!"

But at these words the spirit leaped forth from the bench and grasped hold of the girl, and she cried:

"Oh, do let me take my drying frame down first!"

At these words the spirit let the girl go, and she managed to slip out of the feasting house and run off home.

Old people say that the spirit would never have appeared to the girl if she had not asked after it herself. One should never ask after spirits, or attempt to speak to them, for if so, they will appear.

Told by

Unaleq.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

There was once an old woman, who went out to look to the traps she had set, and took her dog with her. She was anxious to get back to her snow hut the same day, but when darkness fell, she stopped to wait for the moon to come up. She had come to some snow huts, which were deserted, and here she sought out the narrowest, and here she went in to rest. Having climbed up on to the sleeping place, she crept right inside her breeches, closed them at the top, laid her dog down beside her and tried to sleep. (Women's breeches reach almost to the armpits at the top, and when women have to sleep without coverings, they can pull their breeches right over their shoulders and curl up in them as in a sleeping bag).

While she lay there, she heard a voice say:

"Whose a·papa· are you?"

The dog answered of its own accord:

"It is my a·papa·" (an untranslatable word, that was used to frighten people).

But every time the voice asked, the dog answered:

"It is my a·papa·."

At last the dog was silent, but the voice kept on asking. Then the old woman made ready to slip out of the snow hut, taking the little dog in her amaut. The moon was now in the sky, and it had grown light; and now, following her tracks, she hurried homewards as fast as she could. She had already gone a good distance away from the snow hut, when suddenly a crackling flame darted out from the window opening of the snow hut, and the flame rushed along the road after the old woman. The old woman threw herself down beside the tracks, out in the clean snow, where there were no footmarks, hiding her head in the snow; she had turned round, and pulled up the tail of her tunic. The Spirit of the Flame (ikuma·lu·p inua). came rushing forward, but did not notice the old woman, as she lay outside the line of tracks, while she herself distinctly saw the face of the Spirit through the flickering fire in the flame itself with hood pulled down, just like a human being in a hurry: but as the Spirit of the Flame passed by the old woman, it broke up, as it were, into a whole lot of little flames, that flickered for a moment and then went out. Now that the Spirit of the Flame was gone, the old woman tried to get her little dog to stand up, taking it out of the amaut; and the dog was now none the worse, and stood up as lively as could be, there in the snow; and the old woman hurried home with her dog, after having overcome the Spirit of the Flame by her cunning.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.