Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 5

The Angákut or Shamans.

The functions of shamans at the present day are many and various. The most important are as follows:

They must be physicians, curing the sick.

Meteorologists, not only able to forecast the weather, but also able to ensure fine weather. This is effected by travelling up to Sila.

They must be able to go down to Takánakapsâluk to fetch game. a power which they themselves explain thus: nak·aivaglune nᴇrʒutinik manisaidlune, meaning literally: "they must be able to fall down (to the bottom of the sea) in order to bring to light the animals hunted."

They must be able to visit the Land of the Dead under the sea or up in the sky in order to look for lost or stolen souls. Sometimes the dead will wish to have a dear relative who is still alive, brought up to them in the Land of the Dead; the person in question then falls ill, and it is the business of the shaman to make the dead release such souls.

Finally, every great shaman must, when asked, and when a number of people are present, exercise his art in miraculous fashion in order to astonish the people and convince them of the sacred and inexplicable powers of a shaman.

Human beings have not always possessed the power of entering into communication with supernatural forces: they have only attained to the level of their present shamans' capacity through the experiments and experience of many generations.

The material here dealt with concerning the angákut, their training and their powers, I obtained from conversations with Aua and his relative Ivalo; in both cases, based on Iglulik traditions. I have however, also learned much that is valuable in this connection through Angutingmarik, a respected shaman of the Aivilik tribe, from Padloq, and from Inugpasugjuk, an immigrant Netsilingmio in whose house I lived for some time at Pikiuleq (Depot Island) near Chesterfield.

In the very earliest times, men lived in the dark and had no animals to hunt. They were poor, ignorant people, far inferior to those living nowadays. They travelled about in search of food, they lived on journeys as we do now, but in a very different way. When they halted and camped, they worked at the soil with picks of a kind we no longer know. They got their food from the earth, they lived on the soil. They knew nothing of all the game we now have, and had therefore no need to be ever on guard against all those perils which arise from the fact that we, hunting animals as we do, live by slaying other souls. Therefore they had no shamans, but they knew sickness, and it was fear of sickness and suffering that led to the coming of the first shamans. The ancients relate as follows concerning this:

"Human beings have always been afraid of sickness, and far back in the very earliest times there arose wise men who tried to find out about all the things none could understand. There were no shamans in those days, and men were ignorant of all those rules of life which have since taught them to be on their guard against danger and wickedness. The first amulet that ever existed was the shell portion of a sea-urchin. It has a hole through it, and is hence called itᴇq (anus) and the fact of its being made the first amulet was due to its being associated with a particular power of healing. When a man fell ill, one would go and sit by him, and, pointing to the diseased part, break wind behind. Then one went outside, while another held one hand hollowed over the diseased part, breathing at the same time out over the palm of his other hand in a direction away from the person to be cured. It was then believed that wind and breath together combined all the power emanating from within the human body, a power so mysterious and strong that it was able to cure disease.

"In that way everyone was a physician, and there was no need of any shamans. But then it happened that a time of hardship and famine set in around Iglulik. Many died of starvation, and all were greatly perplexed, not knowing what to do. Then one day when a number of people were assembled in a house, a man demanded to be allowed to go behind the skin hangings at the back of the sleeping place, no one knew why. He said he was going to travel down to the Mother of the Sea Beasts. No one in the house understood him, and no one believed in him. He had his way, and passed in behind the hangings. Here he declared that he would exercise an art which should afterwards prove of great value to mankind; but no one must look at him. It was not long, however, before the unbelieving and inquisitive drew aside the hangings, and to their astonishment perceived that he was diving down into the earth; he had already got so far down that only the soles of his feet could be seen. How the man ever hit on this idea no one knows; he himself said that it was the spirits that had helped him: spirits he had entered into contact with out in the great solitude. Thus the first shaman appeared among men. He went down to the Mother of the Sea Beasts and brought back game to men, and the famine gave place to plenty, and all were happy and joyful once more.

"Afterwards, the shamans extended their knowledge of hidden things, and helped mankind in various ways. They also developed their sacred language, which was only used for communicating with the spirits and not in everyday speech."

— — —

When a young man or woman wishes to become a shaman, the first thing to do is to make a present to the shaman under whom one wishes to study. Sometimes two such instructors may be employed at the same time. The present given in the first place must be something valuable, an item from among one's own possessions which has cost the owner some trouble to obtain. Among the Iglulingmiut, wood was the most expensive of all, and it was therefore customary here to pay one's instructor with a tent pole. The wing of a gull was fastened to the pole as a sign or symbol indicating that the pupil should in time acquire the power of travelling through the air to the Land of the Dead up in heaven, or down through the sea to the abode of Takánakapsâluk. The young aspirant, when applying to a shaman should always use the following formula:

"takujumagama": "I come to you because I desire to see."

The gift would then be placed outside the tent, or the house, according as it was summer or winter, and would remain there for some time as a present to the helping spirits that would in time be at the pupil's command. The shaman could have the use of the tent pole afterwards himself, there was no difficulty about that, for the spirits are creatures of air and have no use for wood; they would have the ownership of it all the same, since it had once been given them by a human being, and that was enough for the spirits.

The evening after a shaman has received and set out a gift of this nature, he must do what is called sakavɔq: that is, invoke and interrogate his helping spirits in order to "remove all obstacles" (padzizaiᴀ·rniᴀrlugit) that is, to eliminate from the pupil's body and mind all that might hinder him from becoming a good shaman. Then the pupil and his parents, if he have any, must confess any breach of taboo or other offence they have committed, and purify themselves by confession in face-of-the spirits.

While all this is going on, the shaman remains on the bench behind a skin so hung as to conceal him on the innermost part of the principal seat. The pupil afterwards climbs up and sits down beside him, but not until he has purified himself by confession.

The period of instruction among the Iglulingmiut and Aivilingmiut is not particularly long, especially in the case of men. Some can make do with five days. It is understood, however, that the young shaman, after having been initiated by his experienced tutor, must continue his training on his own account, far from the dwellings of men, in the solitary parts where he can be alone with nature.

During the actual period of instruction he is constantly receiving tuition from one or two shamans, this taking place on the hidden part of the bench behind the curtain. But the shamans are not obliged to remain with the pupil the whole time, as they have special hours for tuition: in the morning, in the middle of the day, in the evening and at night. The pupil must, during the time he is here, never sit on the ordinary coverings spread over the bench, but have a pair of man's breeches laid out under him. He is only allowed to sit on these, and must not leave his place on any account, during the days his instruction lasts. Nor is he, throughout that time, ever allowed to eat his fill, but must eat as little as possible.

While a shaman has a pupil under instruction, he is not allowed to undertake any kind of hunting, and members of the pupil's household are likewise debarred from such occupation.

The first thing a shaman has to do when he has called up his helping spirits is to withdraw the soul from his pupil's eyes, brain and entrails. This is effected in a manner which cannot be explained, but every capable instructor must have the power of liberating the soul of eyes, brain and entrails from the pupil's body and handing it over to those helping spirits which will be at the disposal of the pupil himself when fully trained. Thus the helping spirits in question become familiarised with what is highest and noblest in the shaman-to-be: they get used to the sight of him, and will not be afraid when he afterwards invokes them himself.

The next thing an old shaman has to do for his pupil is to procure him an aɳak·ua by which is meant his "angákoq" i. e. the altogether special and particular element which makes this man an angákoq. It is also called his qaumanᴇq, his "lighting" or "enlightenment", for aɳak·ua consists of a mysterious light which the shaman suddenly feels in his body, inside his head, within the brain, an inexplicable searchlight, a luminous fire, which enables him to see in the dark, both literally and metaphorically speaking, for he can now, even with closed eyes, see through darkness and perceive things and coming events which are hidden from others; thus they look into the future and into the secrets of others.

The first time a young shaman experiences this light, while sitting up on the bench invoking his helping spirits, it is as if the house in which he is suddenly rises; he sees far ahead of him, through mountains, exactly as if the earth were one great plain, and his eyes could reach to the end of the earth. Nothing is hidden from him any longer; not only can he see things far, far away, but he can also discover souls, stolen souls, which are either kept concealed in far, strange lands or have been taken up or down to the Land of the Dead.

An aɳak·ua or qaumanᴇq is a faculty which the old shamans procure for their pupils from the Spirit of the Moon. There are also some who obtain it through the medium of some deceased person among the Udlormiut who is particularly fond of the pupil in question. Or again, it can be obtained through bears which appear in human form; bears in human form are the shamans' best helpers. And finally, it can also be obtained from the Mother of the Caribou, who lives far up inland, and is here called Pakitsumánga.

In addition to the bear, there is also another animal possessing qualities which may be of importance to the shamans. This is the lemming. It is said that the white lemmings fell down from heaven. They therefore possess an altogether peculiar knowledge of the diseases of mankind, and the causes of death. An aɳak·ua derived from the lemmings is therefore considered specially valuable.

But it is not enough for a shaman to be able to escape both from himself and from his surroundings. It is not enough that, having the soul removed from his eyes, brain and entrails, he is able also to withdraw the spirit from his body and thus undertake the great "spirit flights" through space and through the sea; nor is it enough that by means of his qaumanᴇq he abolishes all distance, and can see all things, however far away. For he will be incapable of maintaining these faculties unless he have the support of helping and answering spirits. The Eskimo term for these is: tɔ·ʳɳʳᴀq, pl. tɔ·ʳɳʳät, properly, spirit, also called apᴇrʃᴀq, pl. apᴇrʃät, one that exists to be questioned, an answering spirit. It is these which enable him to continue the work along the lines of instruction imparted by the old shamans. But he must procure these helping spirits for himself; he must meet them in person, and they should preferably be animals appearing in human form. He cannot even choose for himself what sort he will have. They come to him of their own accord, strong and powerful, if the young man shows promise. Fox, owl, bear, dog, shark and all manner of mountain spirits, especially iʲᴇrqät, are reckoned as powerful and effective helpers.

But before a shaman attains the stage at which any helping spirit would think it worth while to come to him, he must, by struggle and toil and concentration of thought, acquire for himself yet another great and inexplicable power: he must be able to see himself as a skeleton. Though no shaman can explain to himself how and why, he can, by the power his brain derives from the supernatural, as it were by thought alone, divest his body of its flesh and blood, so that nothing remains but his bones. And he must then name all the parts of his body, mention every single bone by name; and in so doing, he must not use ordinary human speech, but only the special and sacred shaman's language which he has learned from his instructor. By thus seeing himself naked, altogether freed from the perishable and transient flesh and blood, he consecrates himself, in the sacred tongue of the shamans, to his great task, through that part of his body which will longest withstand the action of sun, wind and weather, after he is dead.

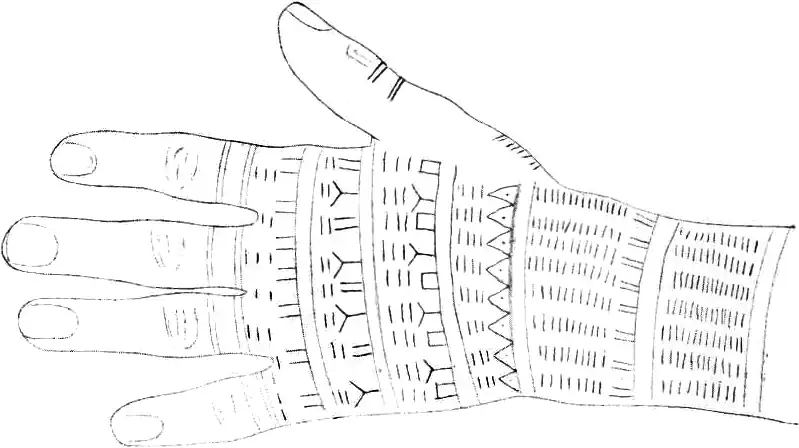

As soon as a young man has become a shaman, he must have a special shaman's belt as a sign of his dignity. This consists of a strip of hide to which are attached many fringes of caribou skin, and these are fastened on by all the people he knows, as many as he can get; to the fringes are added small carvings, human figures made of bone, fishes, harpoons; all these must be gifts, and the givers then believe that the shaman's helping spirits will always be able to recognise them by their gifts, and will never do them any harm.

A man who has just become a shaman must for a whole year refrain from the following:

He must not eat the marrow, breast, entrails, head or tongue of any beasts; the meat he eats must be raw, clean flesh. Women during the first year are subject to even further restrictions, but the most important of all is that they are not allowed to sew a single stitch throughout that year.

The last thing a shaman learns of all the knowledge he is obliged to acquire, is the recitation of magic prayers or the murmuring of magic songs, which can heal the sick, bring good weather or good hunting. One can practise magic words simply by walking up and down the floor of one's house and talking to oneself. But the best magic words are those which come to one in an inexplicable manner when one is alone out among the mountains. These are always the most powerful in their effects. The power of solitude is great and beyond understanding. Here is a method of learning an effective magic prayer:

When one sees a raven fly past, one must follow it and keep on pursuing until one has caught it. If one shoots it with bow and arrow, one must run up to it the moment it falls to the ground, and standing over the bird as it flutters about in pain and fear, say out loud all that one intends to do, and mention everything that occupies the mind. The dying raven gives power to words and thoughts. The following magic words, which had great vitalising power, were obtained by Angutingmarik in the manner above stated:

nunᴀrzuamasuk

uƀva mak·ua —

saunᴇrʒuit silᴀrʒu·p

qᴀqitɔrai —

pᴀrqitɔrai —

he — he — he.

tɔ·ʳɳʳᴀ·rzuk

udludlo

avatiɳnut

audlᴀrit

patqᴇrnagit

uʷai — uʷai — uʷai!

Translation:

Great earth,

Round about on earth

There are bones, bones, bones,

which are bleached by the great Sila

By the weather, the sun, the air,

So that all the flesh disappears,

He — he — he.

And the day, the day,

Go to my limbs

without drying them up,

Without turning them to bones

Uvai, uvai, uvai.

Every good shaman can teach others of his knowledge, and help his pupils over the initial difficulties. Some, however, maintain that the best shamans are those who have never studied under others, but went out at once into the great solitude. This again is denied by those who hold that a good preliminary instruction is a necessary qualification, without which the shaman cannot obtain any benefit from his solitude in the wilds. It is a long schooling that is required before one can honestly undertake all the tasks which unfortunate fellow-creatures may put before one. So seriously are all preparations considered, that some parents, even before the birth of the shaman-to-be, set all things in order for him beforehand by laying upon themselves a specially strict and onerous taboo. Such a child was Aua, and here is his own story:

"I was yet but a tiny unborn infant in my mother's womb when anxious folk began to enquire sympathetically about me; all the children my mother had had before had lain crosswise and been stillborn. As soon as my mother now perceived that she was with child, the child that one day was to be me, she spoke thus to her housefellows:

"'Now I have again that within me which will turn out no real human being.'

"All were very sorry for her and a woman named Ârdjuaq, who was a shaman herself, called up her spirits that same evening to help my mother. And the very next morning it could be felt that I had grown, but it did me no good at the time, for Ârdjuaq had forgotten that she must do no work the day after a spirit-calling, and had mended a hole in a mitten. This breach of taboo at once had its effect upon me: my mother felt the birth-pangs coming on before the time, and I kicked and struggled as if trying to work my way out through her side. A new spirit-calling then took place, and as all precepts were duly observed this time, it helped both my mother and myself.

"But then one day it happened that my father, who was going out on a journey to hunt, was angry and impatient, and in order to calm him, my mother went to help him harness the dogs to the sledge. She forgot that in her condition, all work was taboo. And so, hardly had she picked up the traces and lifted one dog's paw before I began again kicking and struggling and trying to get out through her navel; and again we had to have a shaman to help us.

"Old people now assured my mother that my great sensitiveness to any breach of taboo was a sign that I should live to become a great shaman; but at the same time, many dangers and misfortunes would pursue me before I was born.

"My father had got a walrus with its unborn young one, and when he began cutting it out, without reflecting that my mother was with child, I again fell to struggling within the womb, and this time in earnest. But the moment I was born, all life left me, and I lay there dead as a stone. The cord was twisted round my neck and had strangled me. Ârdjuaq, who lived in another village, was at once sent for, and a special hut was built for my mother. When Ârdjuaq came and saw me with my eyes sticking right out of my head, she wiped my mother's blood from my body with the skin of a raven, and made a little jacket for me of the same skin.

"'He is born to die, but he shall live,' she said.

"And so Ârdjuaq stayed with my mother, until I showed signs of life. Mother was put on very strict diet, and had to observe difficult rules of taboo. If she had eaten part of a walrus, for instance, then that walrus was taboo to all others; the same with seal and caribou. She had to have special pots, from which no one else was allowed to eat. No woman was allowed to visit her, but men might do so. My clothes were made after a particular fashion; the hair of the skins must never lie pointing upwards or down, but fall athwart the body. Thus I lived in the birth-hut, unconscious of all the care that was being taken with me.

"For a whole year my mother and I had to live entirely alone, only visited now and again by my father. He was a great hunter, and always out after game, but in spite of this he was never allowed to sharpen his own knives; as soon as he did so, his hand began to swell and I fell ill. A year after my birth, we were allowed to have another person in the house with us; it was a woman, and she had to be very careful herself; whenever she went out she must throw her hood over her head, wear boots without stockings, and hold the tail of her fur coat lifted high in one hand.

"I was already a big boy when my mother was first allowed to go visiting; all were anxious to be kind, and she was invited to all the other families. But she stayed out too long; the spirits do not like women with little children to stay too long away from their house, and they took vengeance in this wise: the skin of her head peeled of, and I, who had no understanding of anything at that time, beat her about the body with my little fists as she went home, and made water down her back.

"No one who is to become a skilful hunter or a good shaman must remain out too long when visiting strange houses; and the same holds good for a woman with a child in her amaut.

"At last I was big enough to go out with the grown up men to the blowholes after seal. The day I harpooned my first seal, my father had to lie down on the ice with the upper part of his body naked, and the seal I had caught was dragged across his back while it was still alive. Only men were allowed to eat of my first catch, and nothing must be left. The skin and the head were set out on the ice, in order that I might be able later on to catch the same seal again. For three days and nights, none of the men who had eaten of it might go out hunting or do any kind of work.

"The next animal I killed was a caribou. I was strictly forbidden. to use a gun, and had to kill it with bow and arrows; this animal also only men were allowed to eat; no woman might touch it.

"Some time passed, and I grew up and was strong enough to go out hunting walrus. The day I harpooned my first walrus my father shouted at the top of his voice the names of all the villages he knew, and cried: 'Now there is food for all!'

"The walrus was towed in to land, while it was still alive, and not until we reached the shore was it finally killed. My mother, who was to cut it up, had the harpoon line made fast to her body before the harpoon head was withdrawn. After having killed this walrus, I was allowed to eat all those delicacies which had formerly been forbidden, yes, even entrails, and women were now allowed to eat of my catch, as long as they were not with child or recently delivered. Only my own mother had still to observe great caution, and whenever she had any sewing to do, a special hut had to be built for her. I had been named after a little spirit, Aua, and it was said that it was in order to avoid offending this spirit that my mother had to be so particular about everything she did. It was my guardian spirit, and took great care that I should not do anthing that was forbidden. I was never allowed, for instance, to remain in a snow hut where young women were undressing for the night; nor might any woman comb her hair while I was present."

"Even after I had been married a long time, my catch was still subject to strict taboo. If there but lived women with infants near us, my own wife was only allowed to eat meat of my killing, and no other woman was allowed to satisfy her hunger with the meat of any animal of which my wife had eaten. Any walrus I killed was further subject to the rule that no woman might eat of its entrails, which are reckoned a great delicacy, and this prohibition was maintained until I had four children of my own. And it is really only since I have grown old that the obligations laid on me by Ârdjuaq in order that I might live have ceased to be needful.

"Everything was thus made ready for me beforehand, even from the time when I was yet unborn; nevertheless, I endeavoured to become a shaman by the help of others; but in this I did not succeed. I visited many famous shamans, and gave them great gifts, which they at once gave away to others; for if they had kept the things for themselves, they or their children would have died. This they believed because my own life had been so threatened from birth. Then I sought solitude, and here I soon became very melancholy. I would sometimes fall to weeping, and feel unhappy without knowing why. Then, for no reason, all would suddenly be changed, and I felt a great, inexplicable joy, a joy so powerful that I could not restrain it, but had to break into song, a mighty song, with only room for the one word: joy, joy! And I had to use the full strength of my voice. And then in the midst of such a fit of mysterious and overwhelming delight I became a shaman, not knowing myself how it came about. But I was a shaman. I could see and hear in a totally different way. I had gained my qaumanᴇq, my enlightenment, the shaman-light of brain and body, and this in such a manner that it was not only I who could see through the darkness of life, but the same light also shone out from me, imperceptible to human beings, but visible to all the spirits of earth and sky and sea, and these now came to me and became my helping spirits.

"My first helping spirit was my namesake, a little aua. When it came to me, it was as if the passage and roof of the house were lifted up, and I felt such a power of vision, that I could see right through the house, in through the earth and up into the sky; it was the little Aua that brought me all this inward light, hovering over me as long as I was singing. Then it placed itself in a corner of the passage, invisible to others, but always ready if I should call it.

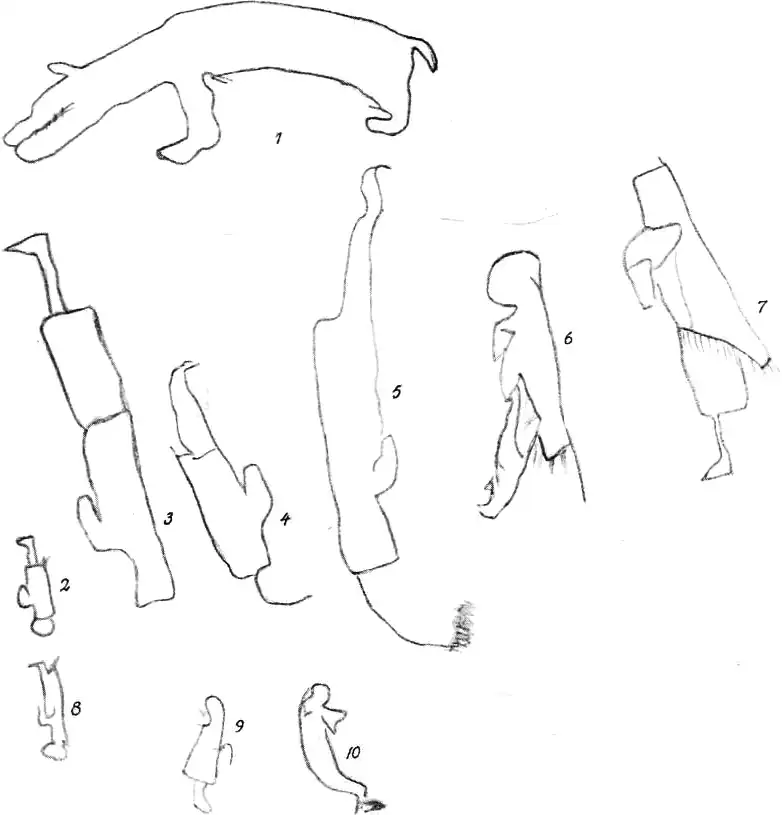

"An aua is a little spirit, a woman, that lives down by the sea shore. There are many of these shore spirits, who run about with a pointed skin hood on their heads; their breeches are queerly short, and made of bearskin; they wear long boots with a black pattern, and coats of sealskin. Their feet are twisted upward, and they seem to walk only on their heels. They hold their hands in such a fashion that the thumb is always bent in over the palm; their arms are held raised up on high with the hands together, and incessantly stroking the head. They are bright and cheerful when one calls them, and resemble most of all sweet little live dolls; they are no taller than the length of a man's arm.

"My second helping spirit was a shark. One day when I was out in my kayak, it came swimming up to me, lay alongside quite silently and whispered my name. I was greatly astonished, for I had never seen a shark before; they are very rare in these waters. Afterwards it helped me with my hunting, and was always near me when I had need of it. These two, the shore spirit and the shark, were my principal helpers, and they could aid me in everything I wished. The song I generally sang when calling them was of few words, as follows:

Joy, joy!

I see a little shore spirit,

A little aua,

I myself am also aua,

The shore spirit's namesake,

Joy, joy!

"These words I would keep on repeating, until I burst into tears, overwhelmed by a great dread; then I would tremble all over, crying only: "Ah-a-a-a-a, joy, joy! Now I will go home, joy, joy!"

"Once I lost a son, and felt that I could never again leave the spot where I had laid his body. I was like a mountain spirit, afraid of human kind. We stayed for a long time up inland, and my helping spirits forsook me, for they do not like live human beings to dwell upon any sorrow. But one day the song about joy came to me all of itself and quite unexpectedly. I felt once more a longing for my fellowmen, my helping spirits returned to me, and I was myself once more".

Niviatsian, aua's cousin, was out hunting walrus with a number of other men near Iglulik; some were in front of him and others behind. Suddenly a great walrus came up through the ice close beside him, grasped him with his huge fore-flippers, just as a mother picks up her little child, and carried him off with it down into the deep. The other men ran up, and looking down through the hole in the ice where the walrus had disappeared, they could see it still holding him fast and trying to pierce him with its tusks. After a little while it let him go, and rose to the surface, a great distance off, to breathe. But Niviatsian, who had been dragged away from the hole through which he had first been pulled down, struggled with arms and legs to come up again. The men could follow his movements, and cut a hole about where they expected him to come up, and here my father actually did manage to pull him up. There was a gaping wound over his collarbone, and he was breathing through it; the gash had penetrated to the lung. Some of his ribs were broken, and the broken ends had caught in one of his lungs, so that he could not stand upright.

Niviatsian lay for a long time unconscious. When he came to himself, however, he was able to get on his feet without help. The wound over the collarbone was the only serious one; there were traces of the walrus's tusks both on his head and in different parts of his body, but it seemed as if the animal had been unable to wound him there. Old folk said that this walrus had been sent by the Mother of the Sea Beasts, who was angry because Niviatsian's wife had had a miscarriage and concealed the fact in order to avoid the taboo.

Niviatsian then went with his companions in towards land, but he had to walk a little way apart from them, on ice free from footmarks. Close to land, a small snow hut was built, and he was shut in there, laid down on a sealskin with all his wet clothes on. There he remained for three days and three nights without food or drink, this he was obliged to do in order to be allowed to live, for if he had gone up at once to the unclean dwellings of men after the ill-treatment he had received, he would have died.

All the time Niviatsian was in the little snow hut, the shaman up at the village was occupied incessantly in purifying his wife and his old mother, who were obliged to confess in the presence of others all their breaches of taboo, in order to appease the powers that ruled over life and death. And after three days, Niviatsian recovered, and had now become a great shaman. The walrus, which had failed to kill him, became his first helping spirit. That was the beginning.

Another time he was out hunting, it was on a caribou hunt up in land, he ran right up against a wolverine's lair. The animal had young ones, and attacked him furiously. It "wrestled" with him all day and night and did not leave hold of him until the sun was in the same place as when it had begun. But in spite of the animal's sharp teeth and claws, there was not a single wound on his body, only a few abrasions. Thus the wolverine also became his helping spirit.

His third helping spirit was Amajorjuk, the ogress with the great amaut on her back, in which she puts the human beings she carries off. She attacked him so suddenly, that he was in the bag already before he could think of doing. The bag closed over him at once, and he was shut in. But he had his knife round his neck, and with this he stabbed the woman in the back, just behind the shoulderblade, and she died. The amaut was as thick as walrus hide, and it took him a long time to cut his way out and escape. But now he discovered that he was altogether naked; he had no idea when he had been stripped of his clothes, nor did he know where he now was, save that it must be far, far inland. Not until he came down close to the sea did he find his clothes, and then he got safely home. But there was a horrible smell of rotten seaweed all over his body, and the smell hung about his house so obstinately that it was half a year before it went away. This ogress also became his helping spirit, and he was now regarded as the greatest of shamans among mankind.

— — —

The methods of attaining magic power here indicated lay particular stress on the inexplicable terror that is felt when one is attacked by a helping spirit, and the peril of death which often attends initiation. Most helping spirits make their first appearance by attacking the person concerned in some violent and mysterious manner. Most dreaded of all helping spirits was im·ap tᴇria·, the sea ermine. This creature is fashioned like the land ermine, but is more slender, lithe and swift, and able to dash up out of the sea so suddenly that defence is out of the question. It has dark, smooth skin, and no hair save a little at the tip of the tail and on the lobes of the ears. When a man was out at sea in his kayak, it would shoot up swiftly as lightning from the depths and slip into his sleeve, and then, running over his naked body, fill him with such a shuddering horror that he almost lost consciousness.

The shaman Niviatsian before mentioned inherited his special qualifications from his mother, Uvavnuk, who obtained her anak'ua in a manner hitherto unknown:

Uvavnuk had gone outside the hut one winter evening to make water. It was particularly dark that evening, as the moon was not visible. Then suddenly there appeared a glowing ball of fire in the sky, and it came rushing down to earth straight towards her. She would have got up and fled, but before she could pull up her breeches, the ball of fire struck her and entered into her. At the same moment she perceived that all within her grew light, and she lost consciousness. But from that moment also she became a great shaman. She had never before concerned herself with the invocation of spirits, but now iɳnᴇru·jäp inua, the spirit of the meteor, had entered into her and made her a shaman. She saw the spirit just before she fainted. It had two kinds of bodies, that rushed all glowing through space; one side was a bear, the other was like a human being; the head was that of a human being with the tusks of a bear.

Uvavnuk had fallen down and lost consciousness, but she got up again, and without knowing what she was doing, came running into the house; she came into the house singing: naluʃa·ruƀlune tamaisalo patsisaialᴇrlugit: there was nothing that was hidden from her now, and she began to reveal all the offences that had been committed by those in the house. Thus she purified them all.

Every shaman has his own particular song, which he sings when calling up his helping spirits; they must sing when the helping spirits enter into their bodies, and speak with the voice of the helping spirits themselves. The song which Uvavnuk generally sang, and which she sang quite suddenly the first evening, without knowing why, after the meteor had struck her, was as follows:

aulᴀrjᴀ·rmaɳa

iɳᴇʀajᴀ·rmaɳa

ᴀqajagin·ᴀrmaɳa.

nᴀ·rʒugʒu·p im·na

aulᴀrjᴀ·rmaɳa

inᴇʀajᴀ·rmaɳa

aulagᴀrinᴀrmaɳa".

Translation:

Has sent me adrift,

It moves me as the weed in a great river,

Earth and the great weather

Move me,

Have carried me away

And move my inward parts with joy."

These two verses she repeated incessantly, aliaɳnᴀrᵈlune i. e. intoxiated with joy, so that all in the house felt the same intoxication of delight, alianaigusulᴇrlutik, and without being asked, began to state all their misdeeds, as well as those of others, and those who felt themselves accused and admitted their offences obtained release from these by lifting their arms and making as if to fling away all evil; all that was false and wicked was thrown away. It was blown away as one blows a speck of dust from the hand:

"taiva·luk, taiva·luk: away with it, away with it!"

But there was this remarkable thing about Uvavnuk, that as soon as she came out of her trance, she no longer felt like a shaman; the light left her body and she was once more quite an ordinary person with no special powers. Only when the spirit of the meteor lit up the spirit light within her could she see and hear and know everything, and became at once a mighty magician. Shortly before her death she held a grand séance, and declared it was her wish that mankind should not suffer want, and she "manivai", i. e. brought forth from the interior of the earth all manner of game which she had obtained from Takánakapsâluk. This she declared, and after her death, the people of her village had a year of greater abundance in whale, walrus, seal and caribou than any had ever experienced before.

The girl who was thrown into the sea by her own father, and had her finger joints so cruelly cut off as she clung in terror to the side of the boat has in a strange fashion made herself the stern goddess of fate among the Eskimos. From her comes all the most indispensable of human food, the flesh of the sea beasts; from her comes the blubber that warms the cold snow huts and gives light in the lamps when the long arctic night broods over the land. From her come also the skins of the great seal which are likewise indispensable for clothes and boot soles, if the hunters are to be able to move over the frozen sea all seasons of the year. But while Takánakapsâluk gives mankind all these good things, created out of her own finger-joints, it is she also who sends nearly all the misfortunes which are regarded by the dwellers on earth as the worst and direst. In her anger at men's failing to live as they should, she calls up storms that prevent the men from hunting, or she keeps the animals they seek hidden away in a pool she has at the bottom of the sea, or she will steal away the souls of human beings and send sickness among the people. It is not strange therefore, that it is regarded as one of a shaman's greatest feats to visit her where she lives at the bottom of the sea, and so tame and conciliate her that human beings can live once more untroubled on earth.

When a shaman wishes to visit Takánakapsâluk, he sits on the inner part of the sleeping place behind a curtain, and must wear nothing but his kamiks and mittens. A shaman about to make this journey is said to be nak·a·ʒɔq: one who drops down to the bottom of the sea. This remarkable expression is due perhaps in some degree to the fact that no one can rightly explain how the journey is made. Some assert that it is only his soul or his spirit which makes the journey; others declare that it is the shaman himself who actually, in the flesh, drops down into the underworld.

The journey may be undertaken at the instance of a single individual, who pays the shaman for his trouble, either because there is sickness in his household which appears incurable, or because he has been particularly unsuccessful in his hunting. But it may also be made on behalf of a whole village threatened by famine and death owing to the scarcity of game. As soon as such occasion arises, all the adult members of the community assemble in the house from which the shaman is to start, and when he has taken up his position — if it is winter, and in a snow hut, on the bare snow, if in summer, on the bare ground — the men and women present must loosen all tight fastenings in their clothes, the lacings of their footgear, the waistbands of their breeches, and then sit down and remain still with closed eyes, all lamps being put out, or allowed to burn only with so faint a flame that it is practically dark inside the house.

The shaman sits for a while in silence, breathing deeply, and then, after some time has elapsed, he begins to call upon his helping spirits, repeating over and over again: "tagva ᴀrqutin·ilᴇrpɔq — tagva nᴇruvtulᴇrpɔq": "the way is made ready for me; the way opens before me!"

Whereat all present must answer in chorus: "taimaililᴇrᵈle": "let it be so!"

And when the helping spirits have arrived, the earth opens under the shaman, but often only to close up again; he has to struggle for a long time with hidden forces, ere he can cry at last:

"Now the way is open".

And then all present must answer: "Let the way be open before him; let there be way for him".

And now one hears, at first under the sleeping place: "Halala — he — he — he, halala — he — he — he!" and afterwards under the passage, below the ground, the same cry: "Halele — he!" And the sound can be distinctly heard to recede farther and farther until it is lost altogether. Then all know that he is on his way to the ruler of the sea beasts.

Meanwhile, the members of the household pass the time by singing spirit songs in chorus, and here it may happen that the clothes which the shaman has discarded come alive and fly about round the house, above the heads of the singers, who are sitting with closed eyes. And one may hear deep sighs and the breathing of persons long since dead; these are the souls of the shaman's namesakes, who have come to help. But as soon as one calls them by name, the sighs cease, and all is silent in the house until another dead person begins to sigh.

In the darkened house one hears only sighing and groaning from the dead who lived many generations earlier. This sighing and puffing sounds as if the spirits were down under water, in the sea, as marine animals, and in between all the noises one hears the blowing and splashing of creatures coming up to breathe. There is one song especially which must be constantly repeated; it is only to be sung by the oldest members of the tribe, and is as follows:

qalume· kanaɳ·a

nuitᴇrtuɳa

supiktertuɳa

aɳnᴇrsɔrte·kpik

in·ᴀrtᴇrtuɳa

qiluje·kpik"

The text, like all magic texts, is not clear; qiluje·kpik is the same as qiluniᴀrpaᵛkit: I will pull you up by the hands. aɳᴇrsɔrte·kpik i. e. nᴇqᴇqaɳ·ilᴇrmät: "because we are without food", qalume· is the term for the hollow on the left of the entrance hole, a hollow in the floor of the house, where water often collects. supiktᴇrtuɳa i. e. wriggle, bore a way up. Orulo translated it as follows:

to help you up:

we are without food,

we are without game.

From the hollow by the entrance

you shall open,

you shall bore your way up.

We are without food,

and we lay ourselves down

holding out hands

to help you up!

An ordinary shaman will, even though skilful, encounter many dangers in his flight down to the bottom of the sea; the most dreaded are three large rolling stones which he meets as soon as he has reached the sea floor. There is no way round; he has to pass between them, and take great care not to be crushed by these stones, which churn about, hardly leaving room for a human being to pass. Once he has passed beyond them, he comes to a broad, trodden path, the shamans' path; he follows a coastline resembling that which he knows from on earth, and entering a bay, finds himself on a great plain, and here lies the house of Takánakapsâluk, built of stone, with a short passage way, just like the houses of the tunit. Outside the house one can hear the animals puffing and blowing, but he does not see them; in the passage leading to the house lies Takánakapsâluk's dog stretched across the passage taking up all the room; it lies there gnawing at a bone and snarling. It is dangerous to all who fear it, and only the courageous shaman can pass by it, stepping straight over it as it lies; the dog then knows that the bold visitor is a great shaman, and does him no harm.

These difficulties and dangers attend the journey of an ordinary shaman. But for the very greatest, a way opens right from the house whence they invoke their helping spirits; a road down through the earth, if they are in a tent on shore, or down through the sea, if it is in a snow hut on the sea ice, and by this route the shaman is led down without encountering any obstacle. He almost glides as if falling through a tube so fitted to his body that he can check his progress by pressing against the sides, and need not actually fall down with a rush. This tube is kept open for him by all the souls of his namesakes, until he returns on his way back to earth.

Should a great shelter wall be built outside the house of Takánakapsâluk, it means that she is very angry and implacable in her feelings towards mankind, but the shaman must fling himself upon the wall, kick it down and level it to the ground. There are some who declare that her house has no roof, and is open at the top, so that she can better watch, from her place by the lamp, the doings of mankind. All the different kinds of game: seal, bearded seal, walrus and whale, are collected in a great pool on the right of her lamp, and there they lie puffing and blowing. When the shaman enters the house, he at once sees Takánakapsâluk, who, as a sign of anger, is sitting with her back to the lamp and with her back to all the animals in the pool. Her hair hangs down loose all over one side of her face, a tangled, untidy mass hiding her eyes, so that she cannot see. It is the misdeeds and offences committed by men which gather in dirt and impurity over her body. All the foul emanations from the sins of mankind nearly suffocate her. As the shaman moves towards her, Isarrataitsoq, her father, tries to grasp hold of him. He think it is a dead person come to expiate offences before passing on to the Land of the Dead, but the shaman must then at once cry out: "I am flesh and blood" and then he will not be hurt. And he must now grasp Takánakapsâluk by one shoulder and turn her face towards the lamp and towards the animals, and stroke her hair, the hair she has been unable to comb out herself, because she has no fingers; and he must smooth it and comb it, and as soon as she is calmer, he must say:

"pik·ua qilusinᴇq ajulᴇrmata": "those up above can no longer help the seals up by grasping their foreflippers".

Then Takánakapsâluk answers in the spirit language: "The secret miscarriages of the women and breaches of taboo in eating boiled meat bar the way for the animals".

The shaman must now use all his efforts to appease her anger, and at last, when she is in a kindlier mood, she takes the animals one by one and drops them on the floor, and then it is as if a whirlpool arose in the passage, the water pours out from the pool and the animals disappear in the sea. This means rich hunting and abundance for mankind.

It is then time for the shaman to return to his fellows up above, who are waiting for him. They can hear him coming a long way off; the rush of his passage through the tube kept open for him by the spirits comes nearer and nearer, and with a mighty "Plu — a — he — he" he shoots up into his place behind the curtain: "Plu-plu", like some creature of the sea, shooting up from the deep to take breath under the pressure of mighty lungs.

Then there is silence for a moment. No one may break this silence until the shaman says: "I have something to say".

Then all present answer: "Let us hear, let us hear".

And the shaman goes on, in the solemn spirit language: "Words will arise".

And then all in the house must confess any breaches of taboo they have committed.

"It is my fault, perhaps", they cry, all at once, women and men together, in fear of famine and starvation, and all begin telling of the wrong things they have done. All the names of those in the house are mentioned, and all must confess, and thus much comes to light which no one had ever dreamed of; every one learns his neighbours' secrets. But despite all the sins confessed, the shaman may go on talking as one who is unhappy at having made a mistake, and again and again break out into such expressions as this:

"I seek my grounds in things which have not happened; I speak as one who knows nothing".

There are still secrets barring the way for full solution of the trouble, and so the women in the house begin to go through all the names, one after another; nearly all women's names; for it was always their breaches of taboo which were most dangerous. Now and again when a name is mentioned, the shaman exclaims in relief:

"taina, taina!"

It may happen that the woman in question is not present, and in such case, she is sent for. Often it would be quite young girls or young wives, and when they came in crying and miserable, it was always a sign that they were good women, good penitent women. And as soon as they showed themselves, shamefaced and weeping, the shaman would break out again into his cries of self-reproach:

"pitᴀqaɳ·icumik, piʃuɳa pitᴀqaɳ·icumik, piʃuɳa pitᴀqᴀrpät ɔqᴀrniᴀrtutit": "I seek, and I strike where nothing is to be found! I seek, and I strike where nothing is to be found! If there is anything, you must say so!"

And the woman who has been led in, and whom the shaman has marked out as one who has broken her taboo, now confesses:

"qalipsulᴀ·rama ɔqᴀrädlaɳ·in·ama kap·iasukluɳa iglume pigama": "I had a miscarriage, but I said nothing, because I was afraid, and because it took place in a house where there were many".

She thus admits that she has had a miscarriage, but did not venture to say so at the time because of the consequences involved, affecting her numerous house-mates; for the rules provide that as soon as a woman has had a miscarriage in a house, all those living in the same house, men and women alike, must throw away all the house contains of qituptɔq: soft things, i. e. all the skins on the sleeping place, all the clothes, in a word all soft skins, thus including also ilupᴇrɔq: the sealskin covering used to line the whole interior of a snow hut as used among the Iglulingmiut. This was so serious a matter for the household that women sometimes dared not report a miscarriage; moreover, in the case of quite young girls who had not yet given birth to any child, a miscarriage might accompany their menstruation without their knowing, and only when the shaman, in such a case as this, pointed out the girl as the origin of the trouble and the cause of Takánakapsâluk's anger, would she call to mind that there had once been, in her menstruation skin (the piece of thick-haired caribou skin which women place in their under-breeches during menstruation) something that looked like "thick blood". She had not thought at the time that it was anything particular, and had therefore said nothing about it, but now that she is pointed out by the shaman, it recurs to her mind. Thus at last the cause of Takánakapsâluk's anger is explained, and all are filled wih joy at having escaped disaster. They are now assured that there will be abundance of game on the following day. And in the end, there may be almost a feeling of thankfulness towards the delinquent. This then was what took place when shamans went down and propitiated the great. Spirit of the Sea.

"The great shamans of our country often visit the People of Day for joy alone; we call them pavuɳnᴀrtut (those who rise up into heaven). The shaman who is about to make the journey seats himself, as in the case of nak·a·jɔq, at the back of the sleeping place in his house. But the man who travels to the Land of Day must be bound before he is laid down behind the curtain; his hands must be fastened behind his back, and his head lashed firmly to his knees; he also must wear only breeches, leaving legs and the upper part of the body naked. When this is done, the men who have bound him must take an ember from the lamp on the point of a knife, and pass it over his head, drawing rings in the air, and say: "niɔʀuniᴀrtɔq aifa·le": "Let him who is now going a-visiting be fetched away".

"Then all lamps are put out, and all visitors in the house close their eyes. They sit like that for a long while, and deep silence reigns throughout the house. But after a time, strange sounds are heard by the listening guests; they hear a whistling that seems to come far, far up in the air, humming and whistling sounds, and then suddenly the shaman calling out at the top of his voice:

'Halala — halalale, halala — halalale!'

"And at the same moment, all visitors in the house must cry: 'Ale — ale — ale!'; then there is a sort of rushing noise in the snow hut, and all know that an opening has been formed for the soul of the shaman, an opening like the blowhole of a seal, and through it the soul flies up to heaven, aided by all those stars which were once human beings. And all the souls now pass up and down the souls' road, in order to keep it open for the shaman; some rush down, others fly up, and the air is filled with a rushing, whistling sound:

"'Pfft — pfft — pfft!'

"That is the stars whistling for the soul of the shaman, and the guests in the house must then try to guess the human names of the stars, the names they bore while living down on earth; and when they succeed, one hears two short whistles: 'Pfft — pfft!' and afterwards a faint, shrill sound that fades away into space. That is the stars' answer, and their thanks for being still remembered.

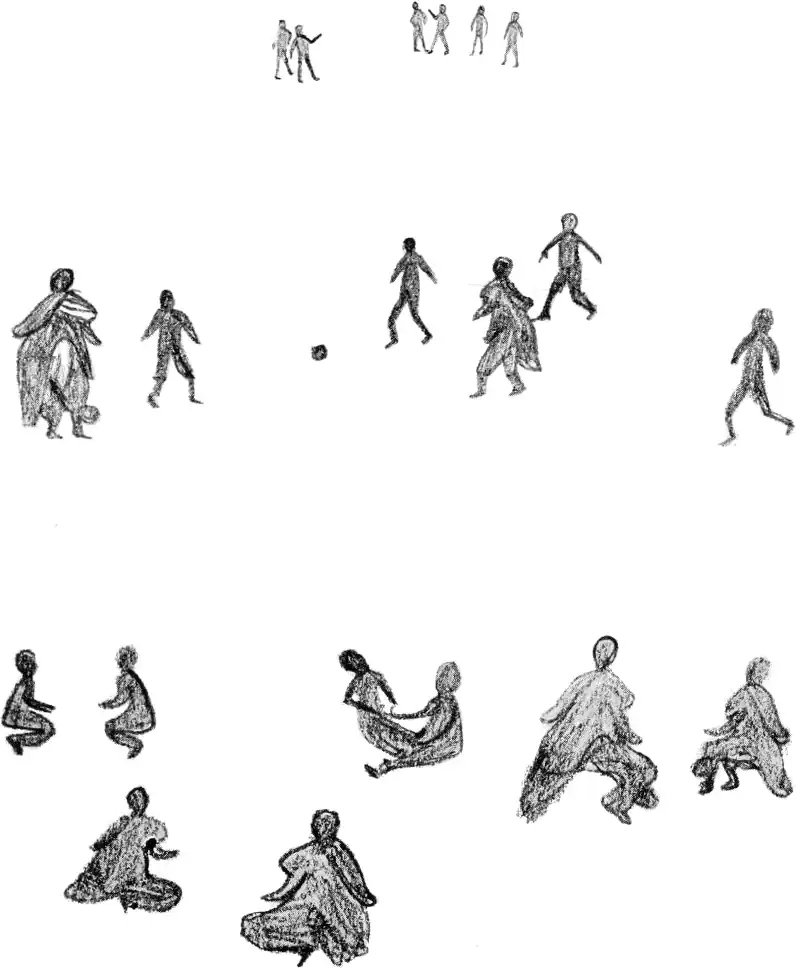

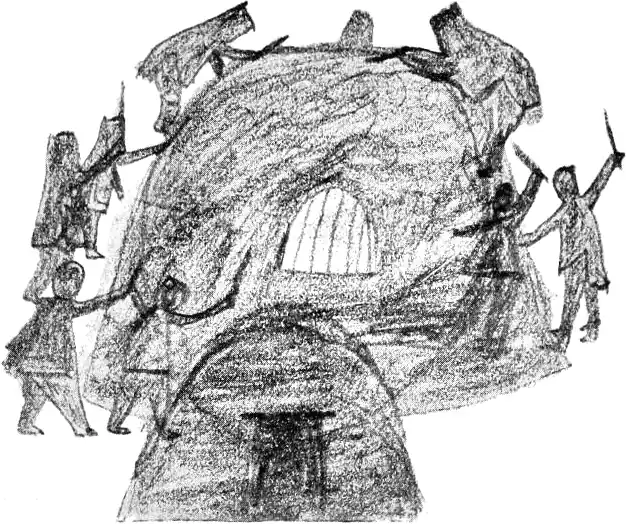

"Often a shaman will remain away for a long time, and his guests will then entertain themselves by singing old songs, always with closed eyes. It is said that there is great joy in the Land of Day when a shaman comes on a visit. They do not perceive him at first, being occupied with their games and laughter and football. But then there is heard the cry: 'niɔʀuᴀrzuit, niɔʀuᴀrzuit!' ringing out over the ground: 'Visitors, visitors'. And at once people come running out of the houses. But the houses have no passage ways, no entrances or exits, and therefore the souls come out from all parts, wherever they fancy, through the wall or through the roof. They shoot right through the house, and though one can see them, they are nevertheless nothing, and there are no holes in the houses where they passed through. And they run towards the visitor, glad to greet him, glad to bid him welcome, for they believe it is the soul of a dead man, like themselves. But then when he says: 'puᵈla·liuvuɳa' 'I am still of flesh and blood', they turn away dissappointed.

"Up in the Land of Day, the thong with which the shaman was bound falls away of itself, and now the dead ones, who are always in high spirits, begin playing ball with it. Every time they kick it, the thing flies out into the air and seems to take the shape of all manner of beings, now a caribou, now a bear, now a human being. They are fashioned by a mass of little loops, which form of themselves at a mere kick from one of the dead.

"When the shaman has amused himself a while among all the happy dead, he returns to his old village. The guests, who are awaiting him with closed eyes, hear a loud bump at the back of the sleeping place, and then they hear the thong he was tied with come rushing down; this does not fall behind the curtain, but down among all the waiting members of the household. Then the shaman is breathless and tired, and only cries:

"'Pjuh — he — he — he!'

"Afterwards he tells of all that he has seen and heard."

— — —

The journey to the Land of the Dead in heaven is not always made, however, merely for pleasure. As long as a shaman is treating a sick person, he must devote himself entirely to this work, and at certain definite times of the day sakavɔq: i. e. he invokes his helping spirits. This is done as a rule four times during the twenty four hours: morning, noon, evening and night. Not until the patient is cured may the shaman resume his everyday business of hunting. Should the treatment fail, and the patient die, this is generally due to witchcraft; more will be said about this elsewhere. Should it be a shaman summoned from another village, however, who is treating the sick person, he may leave his patient before the cure is complete, when the disease lasts a very long time, but must then undertake to leave behind some of his helping spirits in charge. A shaman who has done this will say of himself that he "lacks something"; that he is "not altogether himself" for the helping spirits that remain behind to look after the patient are at part of himself. And as long as a shaman lacks some of his helping spirits, he will not, as a rule, go out hunting; he would feel the power of his senses impaired by the loss.

As long as the shamans are telling of what happened in the olden days, their imagination is naturally borne up by all that distance has rendered great and wonderful. The old accounts gain colour, and again and again we are fold that the generation in which we live is grown feeble and incapable. In the olden days — ah, there were real shamans then!. But now, all is mediocrity; the practice, the theories of all that one should know may still be remembered, but the great art, the dizzying flights to heaven and to the bottom of the sea, these are forgotten. And therefore I was never able to witness a spirit séance which was really impressive in its effect. There might be a certain atmosphere about them, but mostly in the scenes in which all took part, and in the faith and imagination evident among the audience; they might also be uncanny and thrilling as scenes of native life, and even fascinating. One saw terrified, unhappy human beings fighting against fate; one heard weeping and outeries in the dark night of life. But apart from the effect thus produced by the actors and their environment the manifestation of magic in itself was always more or less transparent, and among these tribes at least had nothing of the true spiritual uplift, which they themselves were able to impart to the old traditions. Nevertheless, the shamans were never humbugs or persons who did not believe in their own powers; and it was also extremely rare to meet with any scepticism among the listeners.

I once made the acquaintance of a highly respected shaman named Angutingmarik; when we discussed problems or theories, his answers often impressed me. Nor was he by any means lacking in self-appreciation. Here is his own estimate of his position:

"As to myself, I believe I am a better shaman than others among my countrymen. I will venture to say that I hardly ever make a mistake in the things I investigate and in what I predict. And I therefore consider myself a more perfect, a more fully-trained shaman than those of my countrymen who often make mistakes. My art is a power which can be inherited, and if I have a son, he shall be a shaman also, for I know that he will from birth be gifted with my own special powers."

This Angutingmarik once held a seance at which Jacob Olsen, who was present in company with Therkel Mathiassen, was able to write down all that was said, and I was myself subsequently enabled to test the accuracy of the account by going through it with Jacob Olsen and Angutingmarik together. The description of the proceedings given below is a literal translation. This method of invocation, a very common one among the Aivilingmiut, is an intermediate form between the sakajut type, where the shaman sits behind a curtain of skins on the sleeping place, and the qilajut, of which examples will be given later on. No tricks of any sort are here employed, everything being left to the answering spirits invoked, who give the shaman his cue, whereby he is enabled throughout to make suggestions furnishing occasion for the confessions made. It must of course be borne in mind that in a little Eskimo village, everyone nearly always knows all about everybody else, despite all efforts on the part of any individual to keep anything secret, and however firm his conviction that nobody knows. But should the shaman have nothing definite to go upon, he will keep to matters of ordinary everyday life in which he can be sure that all the women offend against taboo. And he can nevertheless confidently reckon on astonishing all with his knowledge. In the course of his questioning he must always appear to be accusing himself: "Is it my fault?" For he knows that if he does not succeed in ascertaining the cause of the disease, then he is either a poor shaman who cannot, or a black magician who will not cure, and is using his art in the service of evil. It is therefore essential for him to have the listeners' repeated assurance that it is not he who is responsible for the sickness. The listeners on their part must help him to the utmost of their power in eliciting confessions of all offences, for should any such be definitively concealed, it might mean disaster to the whole community. Hence the highly dramatic dialogue which always takes place between the shaman, the audience and the sick person. And all, shaman and audience alike must do what they can to furnish excuses for the offences committed, for such indulgence on the part of human beings tends to appease the anger of the Sea Spirit.

A woman named Nanoraq, the wife of Mákik, lay very ill, with pains all over her body. The patient, who was so ill that she could hardly stand upright, was placed on the bench. All the inhabitants of the village were summoned, and Angutingmarik enquired of his spirits as to the cause of the disease. The shaman walked slowly up and down the floor for a long time, swinging his arms backwards and forwards with mittens on, talking in groans and sighs, in varying tones, sometimes breathing deeply as if under extreme pressure. He says:

"It is you, you are Aksharquarnilik, I ask you, my helping spirit, whence comes the sickness from which this person is suffering? Is it due to something I have eaten in defiance of taboo, lately or long since? Or is it due to the one who is wont to lie beside me, to my wife? Or is it brought about by the sick woman herself? Is she herself the cause of the disease?"

The patient answers:

"The sickness is due to my own fault. I have but ill fulfilled my duties. My thoughts have been bad and my actions evil."

The shaman interrupts her, and continues:

"It looks like peat, and yet is not really peat. It is that which is behind the car, something that looks like the cartilage of the ear? There is something that gleams white. It is the edge of a pipe, or what can it be?"

The listeners cry all at once:

"She has smoked a pipe that she ought not to have smoked. But never mind. We will not take any notice of that. Let her be forgiven, tauva!

The shaman:

"That is not all. There are yet further offences, which have brought about this disease. Is it due to me, or to the sick person herself?"

The patient answers:

"It is due to myself alone. There was something the matter with my abdomen, with my inside."

The shaman:

"I espy something dark beside the house. Is it perhaps a piece of a marrow-bone, or just a bit of boiled meat, standing upright, or is it something that has been split with a chisel? That is the cause. She has split a meat bone which she ought not to have touched."

The audience:

"Let her be released from her offence! tauva!"

The shaman:

"She is not released from her evil. It is dangerous. It is matter for anxiety. Helping spirit, say what it is that plagues her. Is it due to me or to herself?"

Angutingmarik listens, in breathless silence, and then speaking as if he had with difficulty elicited the information from his helping spirit, he says:

"She has eaten a piece of raw, frozen caribou steak at a time when that was taboo for her."

Listeners:

"It is such a slight offence, and means so little, when her life is at stake. Let her be released from this burden, from this cause, from this source of illness. tauva!"

The shaman:

"She is not yet released. I see a woman over in your direction, towards my audience, a woman who seems to be asking for something. A light shines out in front of her. It is as if she was asking for something with her eyes, and in front of her is something that looks like a hollow. What is it? What is it? Is it that, I wonder, which causes her to fall over on her face, stumble right into sickness, into peril of death? Can it indeed be something which will not be taken from her? Will she not be released from it? I still see before me a woman with entreating eyes, with sorrowful eyes, and she has with her a walrus tusk in which grooves have been cut."

Listeners:

"Oh, is that all? It is a harpoon head that she has worked at, cutting grooves in it at a time when she ought not to touch anything made from parts of an animal. If that is all, let her be released. Let it be, tauva!"

Shaman:

"Now this evil is removed, but in its place there appears something else; hair combings and sinew thread."

The patient:

"Oh, I did comb my hair once when after giving birth to a child. I ought not to have combed my hair; and I hid away the combings that none might see."

Listeners:

"Let her be released from that. Oh, such a trifling thing; let her be released. tauva!"

Shaman:

"We have not yet come to the end of her offences, of the causes of her sickness. Here is a caribou breast come to light, a raw caribou breast."

Listeners:

"Yes, we know! Last summer, at a time when she was not allowed to eat the breast of a caribou she ate some all the same. But let her be released from that offence. Let it be taken from her. tauva!"

Shaman:

"She is not yet free. A seal comes forth, plain to be seen. It is wet. One can see how the skin has been scraped on the blubber side; it is all plain as could be."

The patient:

"I did scrape the skin of a seal which my son Qasagâq had killed at a time when I ought not to have touched seal skins."

Shaman:

"It is not yet removed. It has shifted a little way back. Something very like it, something of the same sort, is visible near by."

Listeners:

"Oh that was last summer, when her husband cut out the tusk from a walrus skull, and that was shortly after he had been ill, when he was not yet allowed to touch any kind of game. Let her be released from that. Do let it be taken from her! tauva!"

Shaman:

"There is more to come. There are yet cases of work, of occupations which were forbidden; something that happened in the spring, after we had moved over to this place."

The patient:

"Oh, I gave my daughter a waistbelt made of skin that had been used for my husband's quiver."

Listeners:

"Let this be taken away. Let her be released from it. tauva!"

Shaman:

"It is not yet taken away. She is not released from it as yet. Perhaps it has something to do with the caribou. Perhaps she has prepared caribou skins at a time when she ought not to have touched them."

Listeners:

"She has prepared caribou skins. She helped to stretch out the skins at a time when she was living in the same house with a woman who had her menses. Let her be released from that tauva!"

Shaman:

"She is not freed from guilt even yet. It seems now as if the earth beneath our feet were beginning to move."

Patient:

"I have picked moss at a time when I ought not to have touched earth at all, moss to melt lead with for my husbands rifle bullets."

Shaman:

"There is more yet, more forbidden work that has been done. The patient has not only melted lead for her husband when it was taboo, but she did it while still wearing clothes of old caribou skin, she did it before she had yet put on the garments made from the new autumn skins."

Listeners:

"Oh these are such little things. A woman must not be suffered to die for these. Do let her be released."

Shaman:

"She is not released. It may perhaps prove impossible to release her from these burdens. What is that I begin to see now? It must be blood, unless it is human filth. But it is outside the house, on the ground. It looks like blood. It is frozen, and covered with loose snow. Someone has tried to hide it."

Patient:

"Yes, that was in the autumn. I had a miscarriage, and tried to conceal it, I tried to keep it secret to avoid the taboo."

Listeners:

"This is certainly a great and serious offence. But let her be released nevertheless. Let her be released. tauva!"

Shaman:

"We wish her to get well again. Let all these obstacles be removed. Let her get well! And yet I see, and yet I espy things done which were forbidden. What do I see? It looks as if it were a caribou antler. It looks like that part of the antler nearest the head."

Patient:

"Oh that was a caribou head I once stole in order to eat it, though it was forbidden food for me at the time."

Listeners:

"That was very wrong, but all the same, let her be released, let her be released from that. tauva!"

Shaman:

"There is still something more I seem to see; something that as it were comes and disappears just as I am about to grap it. What is it? Can it be the man Amarualik, I wonder? It looks like him. I think it must be he. His face is bright, but he is blushing also. He is as bright as a living being. It looks as if he wanted to show me something. And yet another person. Who is that? The patient must have no secrets. Let her tell us herself. Let her speak to us herself. Or can it be my cousin Qumangâpik? Yes, it is he. It is Qumangâpik. The size is right, and he has a big nose."

Patient:

"Alas, yes, it is true. Those men have I lain with at a time when I ought not to have lain with any man, at a time when I was unclean."

Listeners:

"It is a very serious offence for a woman to lie with men when she is unclean. But never mind all that. Let her be released, let her get well."

Shaman:

"But there is more yet to come." And turning to his spirit, he says:

"Release her from it all. Release her, so that she may get well. There is still something hereabout, something I can faintly perceive, but cannot yet grasp entirely."

The patient:

"Before the snow came, and before we were allowed to work on the skins of newly captured caribou, I cut up some caribou skin for soles and sewed them on to our boots."

Shaman:

"That is there still! There is more yet. The sources of disease are doubtless all in the patient herself, or can it be that any are in me? Can it be my fault, or that of my helping spirits? Or can those here present as listeners be guilty in any way? Can they have any part in the disease? (This was a reference to Therkel Mathiassen and Jacob Olsen, who had been digging among the ruins. It is considered sacrilege to touch the houses of the dead.) What can be the cause of that which still torments her? Can it be forbidden work or forbidden food, something eatable, something eaten of that which was forbidden, and nothing said? Could it be a tongue?

Patient:

"Alas, yes, I ate a tongue when it was forbidden me to eat caribou tongue."

Listeners:

"tauva, let her be released from this burden, from this offence."

Shaman:

"She is not yet released. There is more yet about forbidden food."

Patient:

"Can it be because I once stole some salmon and ate it a time when salmon was forbidden me?"

Listeners:

"Let her foolishness, let her misdeeds be taken from her. Let her get well."

Shaman:

"She is not yet released. There is more yet; forbidden occupations, forbidden food, stealing. Can it be that she is trying to hide something from us? Is she trying to conceal something, I wonder?"

Listeners:

"Even if she is trying to keep something concealed, let her be released from that, let her get well."

Shaman:

"There are still offences, evil thoughts, that rise up like a heavy mass, and she was only just beginning to get clean. The confessions were beginning to help her."

Listeners:

"Let all evil thoughts disappear. Take away all evil thoughts."

Shaman:

"Many confessions has the patient made, and yet it seems difficult! Can it be that she is beyond cure? But let her get well, quite well. Raise her up. But you cannot. You are not able to relieve her of her illness, though many of the causes have now been removed. It is terrible, it is dangerous, and you, my helping spirit, you whom I believe to be here with us, why do you not raise her up and relieve her of her pain, of her sickness? Raise her up, hold her up. Now once more something appears before my eyes, forbidden food and sinews of caribou." Listeners. "Once more she has combed her hair although she was unclean. Let her be released from that; let it be taken away from her. Let her get well. tauva!"

Shaman:

"Yet again I catch a glimpse of forbidden occupations carried on in secret. They appear before my eyes, I can just perceive them."

Listeners:

"While she was lying on a caribou skin from an animal killed when shedding its coat in the spring, she had a miscarriage, and she kept it secret, and her husband, all unwitting, lay down on the same skin where that had taken place, and so rendered himself unclean for his hunting!"

Shaman:

"Even for so hardened a conscience there is release. But she is not yet freed. Before her I see green flowers of sorrel and the fruits of sorrel."

Listeners:

"Before the spring was come, and the snow melted and the earth grew living, she once, wearing unclean garments, shovelled the snow away and ate of the earth, ate sorrel and berries, but let her be released from that, let her get well, tauva!"

Shaman:

"She is not yet released. I see plants of seaweed, and something that looks like fuel. It stands in the way of her recovery. Explain what it can be."

Listeners:

"She has burned seaweed and used blubber to light it with, although it is forbidden to use blubber for sea plants. But let her be released from that, let her get well. tauva!"

Shaman:

"Ha, if the patient remains obstinate and will not confess her own misdeeds, then the sickness will gain the upper hand, and she will not get well. The sickness is yet in her body, and the offences still plague her. Let her speak for herself, let her speak out. It is her own fault."

Patient:

"I happened to touch a dead body without afterwards observing the taboo prescribed for those who touch dead bodies. But I kept it secret."

Shaman:

"She is not yet released. The sickness is yet in her body. I see snow whereon something has been spilt, and I hear something being poured out. What is it, what is it?"

Patient:

"We were out after salmon, and I happened to spill something from the cooking pot on the snow floor". (When salmon are being sought for, care must be taken never to spill anything from a cooking pot either in the snow, in a snow hut, or on the ground in a tent).

Shaman:

"There are more sins yet. There is more to come. She grows cleaner with every confession, but there is more to come. There is yet something which I have been gazing at for a long time, something I have long had in view ..."

Listeners:

"We do not wish that anything shall be dangerous. We do not wish anything to plague her and weigh heavily upon her. She is better now, it is better now. Let her get well altogether."

Shaman:

"Here you are, helping spirit, dog Púngo. Tell me what you know. Explain youself. Tell me, name to me, the thing she has taken. Was it the feet of an eiderduck?"

Patient:

"Oh, I ate the craw of a goose at a time when I was not allowed to eat such meat."

Listeners:

"Never mind that. Let her be released from that, let her get well."

Shaman:

"But she is not yet released. There is more yet. I can still see a hollow that has been visible to me all the time, ever since I began taking counsel of my helping spirits this evening. I see it, I perceive it. I see something which is half naked, something with wings, I do not understand what this can mean."

Patient:

"Oh, perhaps a little sparrow, which my daughter brought into the tent at a time when I was unclean, when it was forbidden me to come into contact with the animals of nature."

Listeners:

"Oh, let it pass. Let her be excused. Let her get well."

Shaman:

"She is not yet released. Ah, I fear it may not succeed. She still droops, falling forward, she is ill even yet. I see a fur garment. It looks as if it belonged to some sick person. I suppose it cannot be anyone else who has used it, who has borrowed it?"

Listeners:

"Oh, yes, it is true, she lent a fur coat to someone at a time when she was unclean."

Shaman:

"I can still see a piece of sole leather chewed through and through, a piece of sole leather being softened."

Patient:

"The spotted seal from the skin of which I removed the hair, and the meat of which I ate, though it was taboo."

Listeners:

"Let it pass. Let her be released from that. Let her get well."

Shaman:

"Return to life, I see you now returning in good health among the living, and you, being yourself a shaman, have your helping spirits in attendance. Name but one more instance of forbidden food, all the men you have lain with though you were unclean, all the food you have swallowed, old and new offences, forbidden occupations exercised, or was it a lamp that you borrowed?"

Patient:

"Alas yes, I did borrow the lamp of one dead. I have used a lamp that had belonged to a dead person."

Listeners:

"Even though it be so, let it be removed. Let all evils be driven far away, that she may get well."

Here the shaman ended his exorcisms, which had taken place early in the morning, and were now to be repeated at noon and later, when evening had come. The patient was by that time so exhausted that she could hardly sit upright, and the listeners left the house believing that all the sins and offences now confessed had taken the sting out of her illness, so that she would now soon be well again.