Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 4

Death, and Life in the Land of the Dead.

In the very earliest times, there was no death among human beings. Men took women to wife, and women bore children, and mankind grew so numerous that at last there was not room for all. The first human beings lived on an island, and there are those who maintain that it was the island of Mitligjuaq, in Hudson Strait. But the people there propagated their kind, and as none ever left the land where they were born, there were at last so many that the island could not support them. Very slowly, then, one side of the island began to slope down towards the sea. The people grew frightened, for it seemed as if they might slip off and be drowned. But then an old woman began to shout; she had power in her words, and she called out loudly: "tɔquʷaglutik pilᴇrlit taʃ·a nuna tat·ɔrtualu·nialᴇraᵖtigo": "Let be so ordered that human beings can die, for there will no longer be room for us on earth".

And the woman's words had such power that her wish was fulfilled. Thus death came among mankind.

— — —

"Mysterious as the manner in which death came into life, even so mysterious is death itself", says Aua.

"We know nothing about it for certain, save that those we live with suddenly pass away from us, some in a natural and understandable way because they have grown old and weary, others, however, in mysterious wise, because we who lived with them could see no reason why they in particular should die, and because we knew that they would gladly live. But that is just what makes death the great power it is. Death alone determines how long we may remain in this life on earth, which we cling to, and it alone carries us into another life which we know only from the accounts of shamans long since dead. We know that men perish through age, or illness, or accident, or because another has taken their life. All this we understand. Something is broken. What we do not understand is the change which takes place in a body when death lays hold of it. It is the same body that went about among us and was living and warm and spoke as we do ourselves, but it has suddenly been robbed of a power, for lack of which it becomes cold and stiff and putrefies. Therefore we say that a man is ill when he has lost a part of his soul, or one of his souls; for there are some who believe that man has several souls. If then that part of a man's vital force be not restored to the body, he must die. Therefore we say that a man dies when the soul leaves him.

"We have already spoken of how most shamans divide the soul into two parts: inu·sia, of which we say that anᴇrnᴇranut atavɔq: that it "is one with the spirit of life", and the spirit of life is something a living human being cannot do without. The other part of the soul is tᴀrniɳa, perhaps the most powerful part of the soul, and the most mysterious, for while tᴀrniɳa gives life and health, it is at the same time nap·autip ina·: the site of disease, or the spot where any sickness enters in.

"We believe that men live on after death here on earth, for we often see the dead in our dreams fully alive. And we believe in our dreams, for sleep has a ruler, a spirit which we call Aipâtle. This spirit would not show us our dear departed if they did not go on living. Aipâtle helps us also in other ways. When we wake in the morning therefore, we pray to him for what we want, and make offerings of meat to him when we are about to eat. We sacrifice to the spirit, saying: 'aipa·tʟe iluamik piumavuɳa; nᴇrʒutinik tunisigut': 'I wish for what is good, give us luck in our hunting.'

"Old folk declare that when a man sleeps, his soul is turned upside down, so that the soul hangs head downwards, only clinging to the body by its big toe. For this reason also we believe that death and sleep are nearly allied: for otherwise, the soul would not be held by so frail a bond when we sleep. But the Spirit of Sleep is also very fond of the dead, for when we sacrifice meat to him, he gives the souls of the dead meat from our offerings. This also is a sign that death and sleep are nearly allied."

— This account was given by Aua, not, of course, impromptu and all at once, but his explanation is a summary of his own words, in his answers to my numerous questions.

No Eskimo fears death in itself, for all are convinced that it is merely the transition to a new and better form of life. But as mentioned elsewhere, there is also this mystery connected with the soul, that as soon as death has deprived it of the body, it can turn upon the living as an evil and ruthless spirit. The soul of a good and peaceable man may suddenly turn into an evil spirit. There is therefore much intricate taboo associated with death, as the precepts will afterwards show. For the present, it will suffice to state as follows:

When a person dies, the body must be placed in its grave as speedily as possible. If the sun is still in the sky, when death occurs, then it is done at once, but if death occurs after sunset, then the body, if that of a man, must remain in the house or tent for three days, if that of a woman, for four days, or in some places, five. The body is tied up in the caribou skin which was used by the sick person to sleep on, and is set up in a crouching position. This work must be carried out by an old woman, who may have a little girl to help her. The dead body must never be carried out through the ordinary entrance to the dwelling. In the case of a snow hut, it is dragged out through a hole cut in the back wall; in the case of a tent, the skin that forms the tent is lifted up behind the sleeping place, and the body removed that way. In the winter it is generally dragged to the grave, in summer it is carried. The bodies of men and boys are laid in the grave with the face towards the east; women, on the other hand, must face south.

After death, there are two different places to which one may pass either up into heaven to the Udlormiut, or People of Day; their land lies in the direction of dawn, and is the same as the Land of the Moon Spirit. The other place to which the dead may come lies down under the sea. It is a narrow strip of land, with sea on either side; and the inhabitants are therefore called Qimiujârmiut: "the dwellers in the narrow land." The immigrant Netsilingmiut call them Atlet: "those lowest down", for they live in a world below the world in which we live.

Here also dwells the great Sea Spirit Takánakapsâluk.

As already mentioned, persons dying by violence, whether through no fault of their own or by their own hand, pass to Udlormiut; those dying a natural death, by disease, go to Qimiujârmiut. Life in the Land of the Dead is described later under Shamans. It is pleasant both in the Land of Day and in the Narrow Land. In the former, hunting is mainly confined to land animals, in the latter, the denizens of the sea. It appears however, from the stories, that the dead up in heaven can procure marine animals by the aid of the moon, and similarly, the dwellers in the underworld can obtain caribou meat.

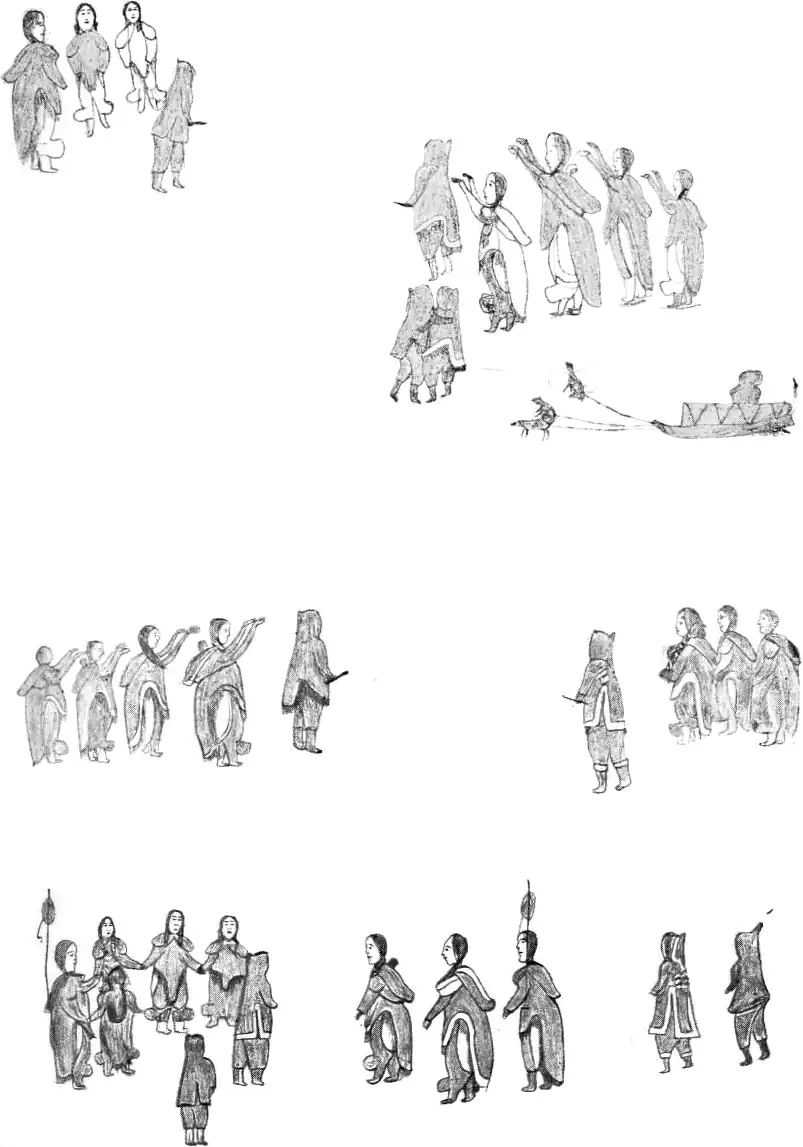

Some hold that all dead persons, whatever the manner of their death, go first to Takánakapsâluk, who then alone determines where they are to dwell; those who have lived a good life without breach of taboo are sent on at once to the Land of Day, whereas those who have failed to observe the ancient rules of life are detained in her house to expiate their misdeeds, before being allowed to proceed to the Narrow Land. The dead suffer no hardship, wherever they may go, but most prefer nevertheless to dwell in the Land of Day, where the pleasures appear to be without limit. Here, they are constantly playing ball, the Eskimos' favourite game, laughing and singing, and the ball they play with is the skull of a walrus. The object is to kick the skull in such a manner that is always falls with the tusks downwards, and thus sticks fast in the ground. It is this ball game of the departed souls that appears as the aurora borealis, and is heard as a whistling, rustling, crackling sound. The noise is made by the souls as they run across the frost-hardened snow of the heavens. If one happens to be out alone at night when the aurora borealis is visible, and hears this whistling sound, one has only to whistle in return and the lights will come nearer, out of curiosity.

Shamans often visit the Udlormiut, not only for pleasure, but also in order to obtain a kind of "blessing", for it brings luck to all the village if one of its shamans makes this aerial journey, and such a shaman is said to be "pavuɳnᴀrtɔq": "he rises to pavuɳa", or that which is highest of all.

Anyone having relatives among the Udlormiut and wishing to join them after death, can avoid being sent to the Qimiujârmiut: the survivors must then lay the body out on the ice instead of burying it on land. Blocks of snow are then set out round the body, not stones, as on land. Often indeed, a small snow hut is built up over the body as it lies. But it is not everyone who can reckon on their surviving relatives' or neighbours' taking all this trouble, and in order to make sure of coming to the Udlormiut, the best way is to arrange one's death oneself. This was done not long since by an old woman named Inuguk, of Iglulik. Her son had perished while out in his kayak, and as she did not live in the same village herself, the news did not reach her until the winter was well advanced. She was old and without other relatives, and could not be certain that others would comply with her wishes when once she was dead; she therefore cut a hole for herself in the ice of a big lake and drowned herself there in order to join her son.

Another example is likewise recorded from Iglulik: an old woman was frozen to death during a severe winter with scarcity of food. When her son learned the news, he went out one cold winter's night and lay down naked in the snow and was frozen to death himself. This he did because he was very fond of his mother, and wished to live with her in the Land of the Dead.

These suicides, however, had some special reason for taking their own lives. The Eskimos' fearlessness of death is more powerfully illustrated in the case of the many old men and women who ended. their lives by hanging themselves. This is done probably not only because the Moon Spirit says that the whole thing is but a moment's dizziness, but possibly also because of an ancient belief that death by violence has a purifying effect. During our first winter in these regions, no fewer than three suicides took place among the few people we knew; two by hanging, the third by cutting the throat. Jacob Olsen was once staying in a village where an old woman committed suicide, and he gives the following account of the matter:

"During my stay at Chesterfield Inlet, I was once up inland hunting caribou with Pilakapsak and his wife Hauna, and in the course of our hunting we came down to a village called Paunat. Here there lived a man named Uhughuanajôq. There were seven others living in the same house with him, among them his mother-in-law, whose name was Aungêq; she was consumptive, and was spitting blood, but not very seriously ill. I often visited this house and talked with the old woman. One evening I went there as usual, and came in through the passage without noticing anything remarkable; the people were sitting about on the bench as they generally did; only I thought they seemed uncommonly silent. It was not the custom here to invite a visitor to sit down, and therefore, having emerged from the narrow entrance hole, I straightened myself up and went across at once to the spot where the sick woman used to lie. On coming nearer, I nearly cried out aloud: I found myself looking into a face that was perfectly blue, with a pair of great eyes projecting right out from the head, and the mouth wide open. I stood there a little to pull myself together, and now perceived a line fastened round the old woman's neck and from there to the roof of the hut. When I was able to speak once more, I asked those in the house what this meant. It was a long time before anyone answered. At last the son-in-law spoke up, and said: 'She felt that she was old, and having begun to spit up blood, she wished to die quickly, and I agreed. I only made the line fast to the roof, the rest she did herself.'

"I could not bear to look at the horrible corpse, which lay stretched out stark naked on the bench, and therefore asked who was going to cover her up for burial. At the same moment there came a widow and a little girl from one of the houses near by. These two gathered all the dead woman's belongings together and laid them on a caribou skin, which they then tied up; next, they began tying up the body itself in another skin, and I stepped forward to help, for there was no one else in the place who dared touch it. Then the woman and the little girl went out, having first armed themselves with their knives, and the rest of the household lay down to sleep. Both men and women laid their knives ready to hand; this they explained was done lest the dead woman's soul should come back and frighten them.

"Early next morning all the sledges were set on edge outside the huts; this was to warn any visitors arriving that there was a dead body in the place.

"For five days the body was kept in the hut; none of the inmates went out, and no work was done. At last, on the fifth day, a hole was cut in the inner wall of the hut, and through this the body and all its belongings were dragged out by means of a long line, right away to the place where the grave was to be. The entire household followed, chatting and laughing as if nothing serious were the matter. A little way from the village, the body was covered up with snow blocks, and hardly was this done when all broke out into violent and uncontrolled lamentation; it was not weeping, but shouting and screaming. Then all went home. But for five days in succession, the grave was visited at the same hour of the day, and always with the same deafening cries. During all that time, no hunting was allowed to be done, and the members of the bereaved household were only allowed to eat food brought them from other houses.

"At last the snow hut was evacuated, a new one built, and life resumed its normal course."

— — —

I myself came in to Chesterfield somewhat later, immediately after an old man named Qalaseq had hanged himself. Both Qalaseq and his wife Qalalâq belonged to the local Catholic Mission, and since the missionary had often impressed on them that human life is God's and that it was therefore unlawful for us human beings to kill ourselves, Qalalâq was now very eager to explain to me that her husband had not died of hanging. He had been ill for a year, and since there was no prospect of his recovery, he had grown tired of life, and had asked his wife to lend death a helping hand, but in such a fashion that he should not die during the hanging itself, but should be released from the hide thong that was to strangle him before he finally expired. Qulalâq accordingly assured me most earnestly that she had strangled him with the thong, but before he was quite dead, she had removed it, and at the same time held up before him a little crucifix, which had been given them by the missionary. Therefore, according to her view, Qalaseq had really died a natural death; they had only "hurried death up a little, as it is apt to be so very slow at times".

Those whose offences against taboo are not wiped out by a violent death, and who have therefore to go to the Sea Spirit for purification before they can pass to the company of the "blessed" in the Narrow Land, have then to pass through a period of purgatory, under the guardianship of Isarrataitsoq, the length of time varying, according to the magnitude of the offences, from one to two years, or even several years. Exceptionally good people may, however, get off with less than a year.

Those who passed to the Land of Day and had thus no need of purification were, however, according to some of the angákut, exposed to one great danger. This was Ululiarnâq. If she could get them to smile before they had quite reached the Land of the Blessed, and thus gain the right to tear out their entrails, they would have to live ever after with that same Ululiarnâq, pale, shrunken creatures with no strength to take part in the others' feasting and games.

The worst offence against taboo which any woman can commit is concealment of menstruation or abortion. Women during the menstrual period are especially unclean in relation to all animals hunted, and may thus expose the entire community to the greatest danger and disaster if they endeavour to conceal their impurity.

In the case of men, unnatural and perverse sex indulgence is regarded as the worst offence. By this is understood coition with animals, especially caribou and seals, which they have just killed, or with live dogs. There were also men who sought to satisfy their lust with the "sacred" earth itself, by making hollows in hummocks of earth and committing onanism there. Such offences are very severely condemned, but do not appear to have been, or even now to be, uncommon. It was possible, however, to palliate one's sins by confessing them to one's neighbours, and it was therefore not difficult to obtain information regarding such cases as soon as one got on the track. The shaman Anarqâq, for instance, whom I have often mentioned, and who spent a great part of the winter with us, had indulged in intercourse with caribou and seals; Qûvik, a young man from Repulse Bay, had made use of the earth, and Inûjaq, our adopted son, had used his dogs. These names are given merely to furnish examples from among those with whom we were personally acquainted.

This method of satisfying sex instinct however, was regarded as punishable, and the place where such souls have to undergo purification before they are suffered to live on in the eternal hunting grounds among the Qimiujârmiut, was in the house of Takánakapsâluk. Here they were laid up on the sleeping place under the same skin as the Sea Spirit's aged father, who tormented them and struck them on the genitals continually for a whole year or more, as long as he was not asleep. As a rule, a year from the date of death was considered sufficient for purification by suffering.

I did not meet anyone among the original inhabitants of the Aivilik or Iglulik who could tell me anything about life after death beyond what has already been stated. Inugpasugjuk however, an immigrant, was able to refer to certain old stories. When I asked him how it was possible to know anything at all about life after death, he referred to a well-known Netsilik shaman named Ánaituarjuk.

It is related that a shaman named Ánaituarjuk was wont to visit the Land of the Dead under the sea. Once when he was down there, he stopped at a big tent. He entered the tent from behind, through a small opening by which a puppy that was tied up there was accustomed to enter. He chose this way because he must not go in the same way as the dead. He came in and found an old couple inside. The old man was making a shaft for a salmon spear, and was saying how dissatisfied he was with his work. He was looking at it critically, when suddenly he glanced up and caught sight of a stranger, and at once entered into conversation with him and said:

"You have come to a rich land and rich people. Outside the tent lie great slabs of fat suet from the caribou. We simply keep it in case our son should ever happen to be away longer than usual at his hunting."

Dead people live on just in the same way as while on earth, and store up food for the winter as they did when alive.

The old man further related as follows:

"There are many salmon up in a lake called Nutiplertôq", and he invited the stranger to settle at Ibjorshivik, as there were many caribou there. At Hiorarshivik there were many seals.

And the old dead man went on:

"In times long past, when I was out hunting at the blowholes one day, I fell through the ice and was drowned. When I came to myself, I was down at the bottom of the sea. Here I saw all round smooth ice free from snow. I looked about and caught sight of two dogs. I caught hold of them and drove off with them. A great stone lay ahead, and my two dogs went one to either side of the stone, and though the traces whereby they were harnessed to my sledge were invisible, they broke all the same, and I lost the dogs, which ran away from me. I then went on without them, on foot, and every time I passed a deserted camp of snow huts, I looked about for something that might be useful to me. At last one day I found a 'feeler' (this is an implement made of bent caribou antler, used to ascertain the shape and course of a blowhole below the surface) that someone had forgotten, and also a harpoon, and with these I began hunting at the blowholes".

Thus Ánaituarjuk told of life after death.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

Inugpasugjuk also stated that Nuliajuk, which was his name for the Sea Spirit, would sometimes carry off human beings, either because they had themselves committed some breach of taboo, or because some near relative of the victim had done so. She did not always punish the one actually guilty, and that was the cruel part of it; for when anyone had done anything wrong, there was no knowing which of his dear ones might suffer for it. Instances were known where Nuliajuk, having carried off a human being, did not kill, but turned the victim into some creature of the sea, so that the man or woman in question would have to live on as a seal or walrus or one of the animals that belonged to her. Only the so-called aɳᴇrlᴀrtukxiᴀq could in such case return to life, with the aid of a shaman. An aɳᴇrlᴀrtukxiᴀq was a human being who had by means of magic words been given the power to come to life again even after having in some way perished by drowning or having been murdered by an enemy.

Those who sought to wrest from Nuliajuk the human beings she had stolen away, must be shamans of such power that they were not afraid to threaten her. If she did not consent of her own free will, they must thrash or beat or otherwise ill-treat her until she gave up the person she had taken. It was to be understood that the soul of the stolen person lived on in the animal, while the body or bones remained with Nuliajuk. An old account of one such case is given in the following story:

Anarte was out in his kayak when it capsized. He himself perished, and was for long a dead man. One day a great shaman was out in a kayak in the same waters. Suddenly he found he could make no progress; it seemed as if he were being held back by something, and when he turned round, he saw behind him Anarte. Then he thought:

"Perhaps Anarte wants to upset my kayak".

But Anarte answered: "I have no thought of upsetting your kayak; I am only here because I have become a sea animal."

Anarte begged the shaman to take him in to shore, and here he became a human being once more. Anarte thanked the shaman for his help, and then asked: "I know that my brother is also dead. When did he die?"

The shaman answered: "It is long since he died."

"At what season of the year did he die?"

"In winter. No human being did him any harm; the Sea Spirit alone was the cause of his death."

The shaman then took the dead Anarte with him to his village, and thus he returned to life. But it was not long before Anarte began making a staff out of straight pieces of earibou antler, and this staff he armed with sharp spikes made of the same material. With this staff he went off one day, when it was calm, down to the edge of the ice. Here he began to look about, to see whether the shining sea was smooth, and he ran on the shining sea as if it were smoothi ice, gliding over it. Now and again he threw himself flat and looked down just as if he were looking through a blowhole on smooth ice. He was a good way out at sea when suddenly he disappeared down under water. In this manner he passed down to the Sea Spirit Nuliajuk. Here he entered the house of Nuliajuk and asked:

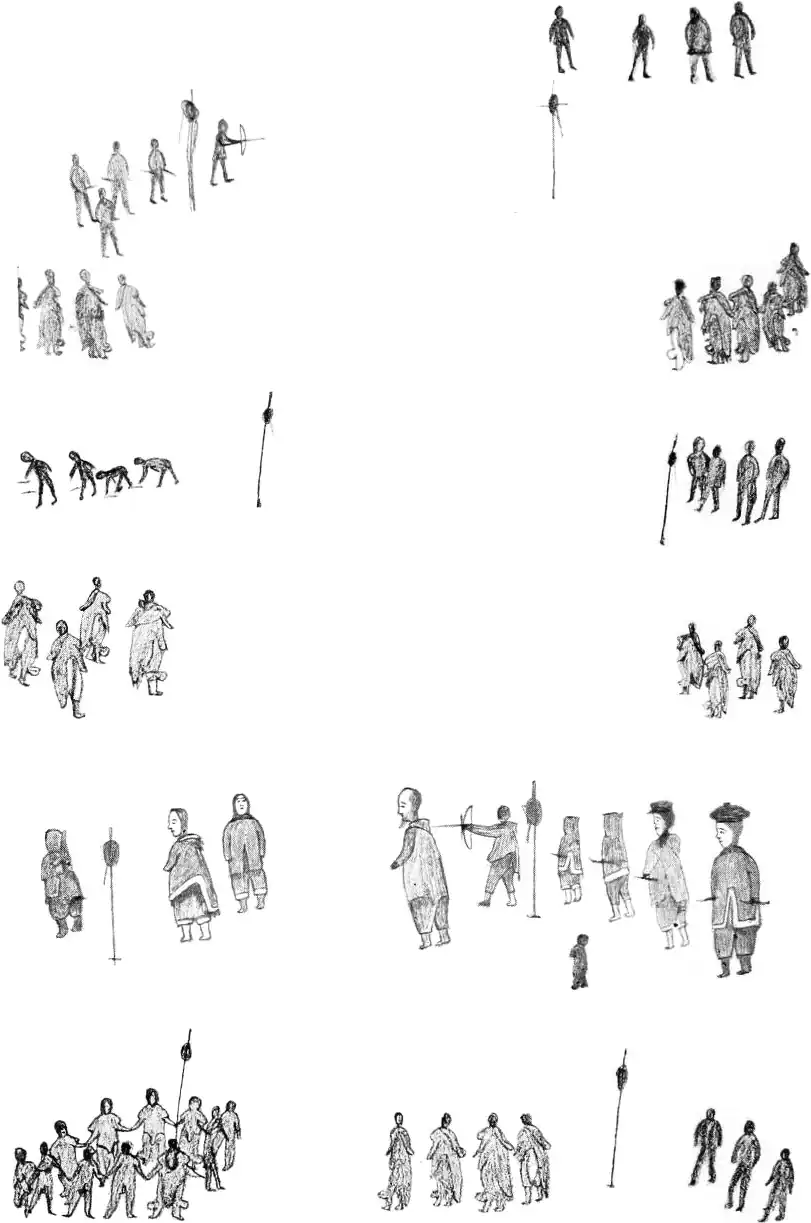

"Where has my brother gone?"

But Nuliajuk did not know. Anarte questioned her eagerly, but kept his horn staff with the sharp spikes still hidden. Now her father Isarrataitsoq began to take part in the talk, and mentioned various breaches of taboo which Anarte's little brother had committed. Then Nuliajuk lifted up the skin hangings and took out a lot of human bones, and putting the bones together, tried to make the skeleton stand up, but the skeleton fell down. Some of the bones were missing, and these she looked for, and setting them into the skeleton with the rest, tried again to make it stand up, but again it fell down. She could not find the missing bones, she said, but now Anarte brought out his stick, and Nuliajuk at once went very red in the face and found some more bones, and now the skeleton could stand up: it was Anarte's brother. If Nuliajuk had not brought out the missing bones. Anarte would have beaten her with his stick. Anarte then went out, letting his brother go first. Then they came up to the surface of the sea, and went on together, in to shore, and people saw them coming, Anarte and his brother, both of whom had been dead for a long time. They now mixed with the people of the village and went about as if they had never been dead, and took part at once in the sports of the young folk, just as they had done before.

Their parents, who were very old, lived a little distance from the village, at a place where they were wont to snare ciderduck; and they knew nothing of all this. A homeless girl was sent to tell them of their sons' return. At first she was afraid to go, but at last she was obliged to all the same. When she came into the old folk's house, one of them at once said: "Come and catch my lice." The girl did so, but she was afraid of the old people, and told a lie in order to have an excuse for running away. Not until she had reached the entrance did she give the message she had been asked to give: "Your sons have come back to the village; they are taking part in the sports with the young people over there." And then she ran back to the village as hard as she could.

"Hi, what's that you say?" Anarte's mother called after her.

"I was told to tell you that your sons are alive and have come back to the village, and they are now taking part in the sports with the young people there".

"Hi, you there" cried the old woman, delighted, "come back and take this little gift".

The girl was afraid they would kill her, and at first she did not dare to go back, and again the old mother called after her: "I won't hurt you. I only want to give you this". And the old woman gave the girl a fine knife by way of thanks, and they went off all three together to the village.

Afterwards the girl was married to one of the two young men who had returned to life, and the old parents lived happily to the end of their days with their two sons.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

— — —

With reference to this story. Inugpasugjuk stated that it was always a very dangerous thing to take another's life. People must have no secrets. All the evil deeds one tried to conceal grew and became dangerous, living evil. If one took the life of another human being, this must likewise not be kept secret from the neighbours, even though it were certain that the relatives of the person slain would have the blood of the slayer in revenge. It was therefore always great, strong, skilful and highly respected folk who dared to kill others. People of the ordinary middle class type took care to mind their own business, and rarely exposed themselves to danger.

The slayer who, for any reason, sought to conceal what he had done, always ran the risk of exposing himself to a danger which might be even greater than that which threatened him from those seeking vengeance. Evil deeds might always recoil upon the evildoer, and the slain persons could, after the expiration of the death taboo, either return as evil spirits frightening all about them to death, or, if it happened to be an aɳᴇrlᴀrtukxiᴀq, come to life again. When this happened, the man who had concealed the fact of his killing would always in some mysterious manner fall a victim to precisely the same death he had intended for his comrade. This is described in the story of Serêraut, or

There was once a man named Serêraut, who was out hunting seal with a companion. The other man had a wife, whom Serêraut wished to have, and when it now chanced that the other caught a bearded seal, Serêraut killed him and sent him to the bottom together with the seal he had caught.

It was summer and winter came. The dead man's wife lived with her mother, who was now old, and as Serêraut had not married her after all when he had killed her husband, they lived in great poverty. But their neighbours assembled in the dancing house and held a feast together.

One evening when they were having a song festival, Serêraut stood at the back of the feasting house looking on. Suddenly the man whom Serêraut had sent to the bottom of the sea stood there, together with the bearded seal, in the midst of the assembly, shooting up through the floor, and bearing in his body the harpoon head and line with which Serêraut had harpooned him. And now he, whom all knew to be dead, stood there and cried aloud: "Serêraut killed me, tied me to a bearded seal I had caught, and sent me to the bottom af the sea." Having uttered these words, he disappeared. The ghost disappeared again through the floor, and when the last little piece of the harpoon line had vanished, there stood Serêraut, his face red as blood, in the background of the assembly.

There was only a moment's pause, and then the dead man again shot up through the floor and cried aloud:

"Serêraut killed me, and sent me to the bottom of the sea with the bearded seal I had caught."

This time he was closer to Serêraut than before, and when he disappeared, Serêraut was even more red in the face than he had been the first time. All now turned to look at him, for it was plain to them that he had lied when he came home and said that a bearded seal had dragged his comrade down into the water and drowned him.

The next time the ghost came up through the floor it was right in front of Serêraut, and again it cried to those in the feasting house:

"Serêraut killed me and sent me to the bottom of the sea with the bearded seal I had caught."

This time, when he disappeared, and the last end of the line he carried with him was just vanishing through the floor of the snow hut, Serêraut himself disappeared through the same hole in the floor, and thus suffered the same fate as he had dealt out to his comrade. But a moment later, the man whom Serêraut had killed came into the feasting house, and this time he had no longer the line fastened to his body with which he had been sent to the bottom of the sea. His mother was sent for at once, and told that her son had returned from the Land of the Dead, and as soon as the old mother heard this, she exclaimed:

"This magic was spoken over my son, that he shall return to life if he dies", and she put on her boots and ran into the feasting house. The old mother came in with her head bowed down towards the floor, and not until she had grasped her son by the feet did she look up and holding him fast, told him that he had been so long coming back to life that she had begun to feel anxious, though she knew that he would always come back even if killed by some enemy. Not until then did she venture to clasp her son's head, and she looked into his face and pressed his head close to her and gave him her breast to suck.

Thus the young hunter returned to life and to his village, but Serêraut disappeared for ever. He had kept his misdeed a secret and therefore could not come to life again.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

Inugpasugjuk further stated that death did not find all beings equally easy to deal with. People who lived passionately, and were dangerous to their surroundings, and treated the precepts of their forefathers with scorn, were as a rule those whom death found most difficult to catch. If therefore, one had an enemy whom it was necessary to get rid of, care must always be taken to cut out the dead man's heart and see it eaten by dogs. When this was done, no magic spell on earth could bring the man to life again, even if he were an aɳᴇrlᴀrtukxiᴀq. This is related of a man named Saugalik.

Saugalik's brother harpooned a bearded seal, but was dragged down by it and drowned. From that day onwards, Saugalik sought only for bearded seals with a harpoon line fixed in their bodies. One day he saw a bearded seal with a harpoon line, and set himself to wait until it should fall asleep. When at last it had fallen asleep, he crept up to it and carried it to an island near by. Here he hung it up by the harpoon line, which was none other than his brother's, and began throwing stones at the creature until it was dead. Though Saugalik had thus killed the bearded seal which has dragged his brother to death, he still felt his revenge was not enough; for he was very fond of his brother.

Despite his sorrow, he took part nevertheless in all song contests, when people assembled in the feasting house. One day, when Saugalik was going out hunting at the blowholes, his daughter said: "What can it be, I wonder, that Saugalik mourns for so deeply? One moment he bursts out crying and sheds tears, the next he is taking part in song contests when everyone is most joyful."

Saugalik heard these words, but took no notice. One day he went out to fetch meat from a store pit, and when he returned, he sent for his daughter and her husband, to entertain them with the meat he had brought home. The daughter and her husband ate as much as they could, and when they could eat no more they had as much meat to take home with them as they could carry.

Saugalik had his bow and arrows hidden on the sleeping place, and only covered with a skin, and now, when his daughter's husband bent down to go out through the passage, he took his bow and arrow and shot him. Nobody approved of this action on the part of Saugalik, and the men of the village therefore killed him. After the three days had passed, during which there is strict taboo for a dead man, Saugalik came back again. He came back to life. And then they killed him a second time. But this time it was the same as before. When the three days of strict taboo had passed after his death, he came back alive and well as ever. Then they cut off his head, but when the usual three days had passed, he returned once more with his eyes in his chest. Then they killed him for the fourth time, but this time they cut out his heart and threw it to the dogs, and the dogs ate it. And thus at last they managed to kill him, and he never returned again to his village.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

— — —

It is necessary to be careful when speaking about death. Death must not be offended, and that is why people are loth to mention the names of deceased relatives. Some indeed are even afraid to utter the name of Nuliajuk, and simply say Takána, "the one down there".

There is a story told of how careful one should be in speaking of death. One must never say anything about death in fun, for in such case, that which was not meant in earnest, or at any rate meant only as a threat, may very often become reality. Thus it happened with Sautlorasuaq, who had once in a passion threatened to come again as a ghost.

Sautlorasuaq went out one day with his family on a journey to visit his cousin Utsugpatlak. On arriving at the village, they built a snow hut. As soon as they had finished building their snow hut, they went over to Utsugpatlak's house to eat, taking meat of their own in with them. When Utsugpatlak saw that his cousin had brought his own food, he was angry, and leapt towards him. He tore off a piece of the meat with his teeth, snatched it from Sautlorasuaq, and threw it to the dogs. For he took it as a sign that his cousin did not think he had food in the house, since he thus brought food of his own in with him, although he was a guest.

But Sautlorasuaq was angry, and said:

"When I die, I will come and haunt you, and you can do the same to me if you die first."

Many years after, Sautlorasuaq died. When he was on the point of death, he said:

"When I die, my soul will arise again in the shape of a bear. Therefore do not hurt the bear when you see it."

He died, and after the days of taboo for a dead man were over, true enough, there came a bear out of the house where Sautlorasuaq lay dead. The neighbours went after the bear, but the bear ran away. One of the men who was pursuing the bear said:

"It looked as if that might be Sautlorasuaq".

At these words, most of the men who were pursuing the bear turned back, but there were still some that kept on in chase. The swiftest of them got the bear and brought the dead bear home to his dwelling. But now it came to pass that the man who had killed the bear died shortly after, his windpipe burst. And all those who had eaten of the bear died likewise.

Thus Sautlorasuaq sought to avenge himself on his cousin by appearing to him in the guise of a bear. Afterwards, he was also seen in the form of a fox, and Utsugpatlak went about in deadly fear of what his cousin might hit upon next. At last he fell ill, while out on a journey, and while those with him were building a snow hut, he lay there close by waiting for the house to be finished. While he lay there, he heard the voice of Sautlorasuaq beside him, and the voice said:

"I have endeavoured to get at you in many different ways. But since it was always a failure, I will now leave you in peace."

That night Utsugpatlak slept in peace, and as he thereafter obtained the rest he needed, he got well again.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

Where a village strictly observes the taboo prescribed in case of death, and otherwise holds by the ancient precepts, no one ever need go in fear of the dead, once their breathing has been severed (kipisimalᴇrpän). But should anyone take it into his head to make a noise about the place where the soul has not yet left the body, or should work, or drive a sledge, go out hunting or arrange a song contest, then the dead man will return as an evil spirit. There are, however, never any definite rules for anything, for it may also happen that a deceased person may in some mysterious manner attack surviving relatives or friends whom he loves, even when they have done nothing wrong. Inugpasugjuk can give no explanation of this beyond suggesting that the dead perhaps do this out of longing for those whose companionship they lack in the Land of the Dead; and by frightening them to death or otherwise causing them to perish so that they die they would then be united at once in the hunting grounds of the dead, and the whole family could live on together. Often a ghost will appear in the form of a lethal fire, and in this, Inugpasugjuk's traditions agree entirely with what is known from of old in Greenland. It is stated there that a bright flame often shoots up from old graves, because the dead person has turned to fire.

As an instance of the manner in which a deceased father fetched his wife and son up to his hunting grounds in the Land of the Dead, we have the following story:

There was once a woman who lost her husband. When a year had passed since his death, the woman drove out with her two sons, a half-grown youth and a little boy, to visit her husband's grave. It was evening by the time they reached the grave, and therefore they built a snow hut close by. While the woman was building, with her elder son, they had laid the little boy down among some skins, and now they perceived that the child lay there laughing all the time. Then the woman spoke, and said:

"It is the child's father, trying to tickle him to death. He will also try to tickle us to death. Make haste therefore and harness your dogs and let us hurry away."

The young man did so, and the ghost came as a fire, as a flame, out of the grave, and when it had tickled the little child to death, it fell upon the woman also and killed her in the same way. After that, it set off as a flaming fire in chase of the son who was driving away, and appeared suddenly on the sledge, flaming like a torch. But the young man struck at the fire with the shaft of his whip, and every time he did so, the flame drew back a little. All the way home he fought with the flame, until he reached his dwelling unharmed. All the neighbours were just then assembled in the feasting house, and he dashed in there and told them what had happened, and that his father's ghost pursued him in the shape of a fire. But there was a shaman present, and he charmed the fire away, he destroyed it, and thus saved the young man's life.

Told by

Inugpasugjuk.

(immigrant Netsilingmio).

— — —

Human beings are thus helpless in face of all the dangerous and uncanny things that may happen in connection with death and the dead. It is not sufficient to observe all taboo or live entirely according to the precepts of the ancients. An act for which one is not personally responsible may prove disastrous, and one may die without the least idea of it. And even though one may not fear to pass to the eternal hunting grounds, there is nevertheless the natural tendency of all living things to cling to life on earth. But whether the misfortune come from the Sea Spirit, from the weather, or from the deceased, ordinary human beings can do nothing to affect their fate. The only ones who can intervene and penetrate into all that is hidden from ordinary mortals are the angákut (aɳak·ut), the shamans.