Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 10

Songs and Dances, Games and Pastimes.

The Eskimo temperament finds a lively and characteristic expression in the mode of entertainment chosen as soon as but a few individuals are gathered together. The natural healthy joy of life must have an outlet, and this is found in boisterous games as well as in song and dance. Underlying all the games is the dominant passion of rivalry, always seeking to show who is best in various forms of activity: the swiftest, the strongest, the cleverest and most adroit. There are many different kinds of games, often in the form of gymnastic exercises, which are associated with the festivals invariably held when guests are to be entertained, and the party as a whole are otherwise fit and well, with meat enough for a banquet. There are ball games, races, trials of strength, boxing contests, archery etc.; but the same spirit of rivalry which makes all this kind of sport exciting, is also found in the song contests which are held in the feasting house as the culmination of all the merry items in the entertainment. And where there are several families living in one village, there is no need of visitors to provide the occasion, the party is then sufficient in itself. The autumn and the dark season naturally form the great time for song; as if it were desired to chase away the thoughts of the winter now inevitably approaching, in the course of which so much may happen in the way of unlooked-for, undesirable events, if Sila and the other guiding powers are not favourably disposed towards mankind.

The great song festivals at which I have been present during the dark season are the most original and the prettiest kind of pastime I have ever witnessed. Every man and every woman, sometimes also the children, will have his or her own songs, with appropriate melodies, which are sung in the qaç·e, the great snow hut which is set up in every village where life and good spirits abound. Those taking part in a song festival are called qaç·iʃut; the poem recited is called pisᴇq, the melody of a song iᵛɳᴇrut: and to sing is iᵛɳᴇrtᴀ·rnᴇq; the combination of song, words and dance is expressed by the word mumᴇrnᴇq: "changing about"; having reference to the fact that as soon as the leading singer has finished, another comes forward; he sings: mumᴇrpɔq, plural mumᴇrtut. The chorus, which must always accompany the leading singer, who beats time with his drum while dancing, is called iɳiɔrtut: those who accompany in song.

A qaç·e is heated and lighted by one or more lamps; to make it thoroughly festive, there must be no lack of blubber, and that is one reason why it is difficult to celebrate these festivals unless there is abundance of everything. If the hunting has been such as to require economy, no special feasting house is built, but the whole community assemble in the largest house in the place. An essential preliminary to the success of the general entertainment is the careful praetising of the songs by each family at home in their own huts. These people have no written characters, and no means of breaking the monotony of indoor life but what they can make for themselves, so that the songs are apt to be their chief method of entertainment. Where all are well, and have meat enough, everyone is cheerful and always ready to sing, consequently there is nearly always singing in every hut of an evening, before the family retire to rest. Each sits in his or her own usual place, the housewife with her needlework, the husband with his hunting implements, while one of the younger members takes the drum and beats time; all the rest then hum the melodies and try to fix the words in their minds.

When the song festivals are held in the qaç·e, the party assemble there every evening. Among villagers still living inland, because their womenfolk have not yet finished their needlework, the gathering begins early in the afternoon, and lasts until late in the evening, song and dance continuing uninterruptedly all the time. Should there happen to be visitors, the entertainment may last all night. The men who have most meat contribute the most delicious kinds of food, and the festival opens with a great banquet, at which everyone may eat as much as he can stuff.

Then, when the singing is to begin, the performers are drawn up in a circle, the men inside, the women outside. The one who is to lead off with an original composition now steps forward, holding the large drum or tambourine, called qilaut, a term possibly related to the qilavɔq previously mentioned: the art of getting into touch with spirits apart from the ordinary invocation. For qilaut means literally: "that by means of which the spirits are called up". This term for the drum, which with its mysterious rumbling dominates the general tone of the songs, is doubtless a reminiscence of the time when all song was sacred. For the old ones believe that song came to man from the souls in the Land of the Dead, brought thence by a shaman; spirit songs are therefore the beginning of all song. And the direct relation of the songs to the spirits is also explained by the fact that every Eskimo who under the influence of powerful emotion loses control of himself, often breaks into song, whether the occasion be pleasurable or the reverse.

Compare here, the manner in which Aua the shaman could suddenly fall a prey to an inexplicable dread, burst into tears and sing the song of joy. Or the case of Uvavnuk, when struck by the meteor suddenly bursting into song over the theme of all that moved her and made her a shaman (p. 123).

As a rule, each leading singer has to sing a certain number of songs, but not too many; three, for instance, and often it is so arranged that the one who comes after him must sing at least as many as the first. Should he fail to equal the number of his predecessor, he is accounted a poor singer, a man without experience or imagination. Before the song festival begins, the drum has to be carefully tuned up. The skin, which is stretched on a wooden frame, sometimes quite round, sometimes oval in shape, is made from the hide of a caribou cow or calf with the hair removed. This is called ija·, the "eye" of the drum, and must be moistened with water and well stretched before use. Only thus will it give the true, mysterious rumbling and thundering sound.

The singer generally opens with a modest declaration to the effect that he cannot remember his insignificant songs. This is intended to suggest that he considers himself but a poor singer; the idea being, that the less one leads the audience to expect, the humbler one's estimation of one's own performance, the more likelihood there will be of producing a good effect. A conceited singer, who thinks himself a master of his art, has little power over his audience.

The singer stands in the middle of the floor, with knees slightly bent, the upper part of the body bowed slightly forward, swaying from the hips, and rising and sinking from the knees with a rhythmic movement, keeping time throughout with his own beating of the drum. Then he begins to sing, keeping his eyes shut all the time; for a singer and a poet must always look inward in thought, concentrating on his own emotion.

There are very precise rules for the use of the qilaut. The skin of the drum itself is never struck, the edge of the wooden frame being beaten instead, with a short and rather thick stick. The drum is held in the left hand, by a short handle attached to the frame, and as it is fairly heavy, and has to be constantly moved to and fro, it requires not only skill, but also considerable muscular power, to keep this going sometimes for hours on end. The singer's own movements, the beating of the drum, and the words of the song must fit in one with another according to certain definite rules, which appear easy and obvious to an onlooker, but anyone trying to imitate the performance will inevitably get out of time. It is a great art to keep one's attention fixed on the rhythmic movements of the body, the beats of the drum, which must accompany, yet not coincide with, the bending of the knees; then there is also the time of the melody itself, which must likewise follow the movements, and finally the words, which have to be remembered very accurately, with the inconceivably numerous repetitions recurring at certain particular parts of the song. And the singer, while keeping all this in mind, must at the came time inspire his chorus so that it is led up to that ecstasy which can at times carry a simple melody for hours, supported only by a refrain consisting of ajaja, ajaja. I have been present at song festivals lasting for 14–16 hours, which shows what song means to these people. Imagine a concert in any civilised community lasting for that length of time! But the secret of the Eskimos' endurance lies of course in the fact that they are simple and primitive natures, working themselves up collectively into an ecstasy which makes them forget all else.

I have many a time endeavoured to learn their songs so as to be able myself to take part in a performance at the qaç·e, but with no great success. I never found any difficulty in making up a song that should fulfil the ordinary requirements, though it was not easy to equal the natural primitive temperament in its power of finding simple and yet poetic forms of expression; but as soon as I tried to accompany myself on the drum, with the very precise movements of the body that go with it, I invariably got out of time, and thus lost my grip of those whom it was my business to inspire as my chorus. These attempts of my own to take part gave me an increased respect for this particular form of the art of singing, and now that I have to describe, as far as I can, the performance as a whole, I can only say that the general feeling, the emotional atmosphere in a qaç·e among men and women enlivened by song is something that cannot be conveyed save by actual experience. Some slight idea of it may perhaps be given some day, when the "talking film" has attained a higher degree of technical perfection — if it gets there in time; it would then have to be by a combination of the songs in the Eskimo tongue and the dancing in living pictures. Unfortunately, I was unable to record their melodies on the phonograph, as our instrument was out of order. I hope then at some future date to be able to revert to this complicated but humanly speaking highly interesting subject; for the present, I must confine myself to the Eskimos' own view.

There are various kinds of songs. Firstly those inspired originally by some great joy or sorrow, in a word, an emotion so powerful that it cannot find vent in ordinary everyday language. Then there are songs merely intended to give the joy of life, of hunting, rejoicing in the beasts of the chase, and all the good and ill that man can experience when among his fellow men. Then again, every man who aspires to be considered one with any power of gathering his neighbours together must also have challenged some one else to a song contest: and in this he must have his own particular rival, one whom he delights to compete with, either in the beauty of his songs as such, or in the skilful composition and delivery of metrical abuse. He describes the experiences which he considers most out of the ordinary, and best calculated to impress others with the idea of his own prowess as a hunter and courage as a man. Two such opponents in song contests must be the very best of friends; they call themselves, indeed, iglɔre·k, which means "song cousins", and must endeavour, not only in their verses but also in all manner of sport, each to outdo the other; when they meet, they must exchange costly gifts, here also endeavouring each to surpass the other in extravagant generosity. Song cousins regard themselves as so intimately associated that whenever they meet, they change wives for the duration of their stay. On first meeting after a prolonged absence, they must embrace and kiss each other by rubbing noses.

Song cousins may very well expose each other in their respective songs, and thus deliver home truths, but it must always be done in a humorous form, and in words so chosen as to excite no feeling among the audience but that of merriment.

These cheerful duels of song must not be confused with those songs of abuse which, albeit cast in humorous form for greater effect, have nevertheless an entirely different background in the insolence with which the singer here endeavours to present his opponent in a ludicrous light and hold him up to derision. Such songs always originate in some old grudge or unsettled dispute, some incautious criticism, some words or action felt as an insult, and perhaps breaking up an old friendship. The only means then of restoring amicable relations is by vilifying each other in song before the whole community assembled in the qaç·e. Here, no mercy must be shown; it is indeed considered manly to expose another's weakness with the utmost sharpness and severity; but behind all such castigation there must be a touch of humour, for mere abuse in itself is barren, and cannot bring about any reconciliation. It is legitimate to "be nasty", but one must be amusing at the same time, so as to make the audience laugh; and the one who can thus silence his opponent amid the laughter of the whole assembly, is the victor, and has put an end to the unfriendly feeling. Manly rivals must, as soon as they have given vent to their feelings, whether they lose or win, regard their quarrel as a thing of the past, and once more become good friends, exchanging valuable presents to celebrate the reconciliation. Sometimes the songs are accompanied by a kind of boxing, the parties striking each other with their fists, first on the shoulders, then in the face, not as a fight, but only to test each other's endurance and power of controlling emotion despite the pain. This form of boxing, which is called tiklu·t·ut, is well known among the Aivilingmiut and Iglulingmiut, but is especially prevalent among the Netsilingmiut.

I shall frequently have occasion to revert to the Eskimo songs when dealing with the various tribes encountered on my last journeys. The best singers I met during our winters at Hudson's Bay were Aua and his brother Ivaluardjuk, whose most characteristic song I have already given in the introductory section. When sung, it produced an altogether extraordinary effect on those present. And anyone who understands the Eskimo tongue will be able to appreciate the great power of expression and the elegance of form in the original text. For my own part, what impressed me most was the individuality of conception in the poet's endeavouring to further the expression of his inspiration, or of his hunting experience, by lying down on the ice on a winter's day and in a vision recalling the contrast to the harshness of the moment in his fight with the gnats, which are the pests that accompany the delightful warmth of summer. The Eskimo poet does not mind if here and there some item be omitted in the chain of his associations; as long as he is sure of being understood, he is careful to avoid all weakening explanations. Here is the old man, his limbs awry with the gout, shivering with cold one bitter winter's day, and, in order to give warmth to his description of a distant memory of the chase, he cries out into the driving snow:

These two pests

Come never together.

I lay me down on the ice,

Lay me down on the snow and ice.

Till my teeth fall chattering.

It is I.

Aja — aja — ja.

This reference to the mosquitoes at once calls up recollections of summer in the minds of his hearers, and he drives them away again at once to bring forward the situation he has in view. The same poetic adroitness is also apparent in Tûglik's play song, which is given in the description of the shaman Unaleq. This also must be heard to produce the full effect; it needs the clear children's voices to give it at its best. The description of the evil days of dearth could not be more intensely given than in the second and sixth verses, where the subject is introduced as follows:

Plague us every one,

Stomachs are shrunken,

Dishes are empty.

The hallucinations which almost invariably accompany actual starvation are then given in the following lines, where things of solid earth become but as a floating mirage to those whose entrails are racked with emptiness:

All about us,

Skin boats rise up.

Out of their moorings,

The fastenings go with them,

Earth itself hovers

Loose in the air.

aja· — ja· — japape.

aja· — ja· — japape,

And then comes finally the joyous vision of food:

Of pots on the boil?

And lumps of blubber

Slapped down by the side bench?

aja· — ja· — japape

Hu — hue! Joyfully

greet we those.

who brought us plenty!

This little song, which is given on p. 41. is nothing but a scrap of nursery rhyme, known to all children at play, yet it shows to the full the high level of Eskimo poetry.

But when one tries to talk to one of these poets on the subject of poetry as an art, he will of course not understand in the least what we civilised people mean by the term. He will not admit that there is any special art associated with such productions, but at the most may grant it is a gift, and even then a gift which everyone should possess in some degree. I shall never forget Ivaluardjuk's astonishment and confusion when I tried to explain to him that in our country, there were people who devoted themselves exclusively to the production of poems and melodies. His first attempt at an explanation of this inconceivable suggestion was that such persons must be great shamans who had perhaps attained to some intimate relationship with the spirits, these then inspiring them continually with utterances of spiritual force. But as soon as he was informed that our poets were not shamans, merely people who handled words, thoughts and feelings according to the technique of a particular art, the problem appeared altogether beyond him. And it is precisely in this that we find the difference between the natural temperament of the uncultured native and the mind of more advanced humanity; between the Eskimo singer and the poet of any civilised race; the work of the latter being more a conscious attempt to create beauty and power in rhythm and rhyme. The word "inspiration", as we understand it, does not, of course, exist for the Eskimo; when he wishes to express anything corresponding to our conception of the term, he uses the simple phrase: "to feel emotion". But every normal human being must feel emotion at some time or other in the course of a lifetime, and thus all human beings are poets in the Eskimo sense of the word.

In order further to make clear Ivaluardjuk's ideas, I would once more refer to the woman Uvavnuk, who one dark night experienced her great emotion, the decisive inspiration of her life, through the medium of a meteor which came rushing down out of space and took up its abode in her, so that she, who had until then been quite an ordinary person, became clairvoyant, became a shaman, and could sing songs that had in themselves the warmth of the glowing meteor.

Finally, the Eskimo poet must — as far as I have been able to understand — in his spells of emotion, draw inspiration from the old spirit songs, which were the first songs mankind ever had; he must cry aloud to the empty air, shout incomprehensible, often meaningless words at the governing powers, yet withal words which are an attempt at a form of expression unlike that of everyday speech. Consequently, no one can become a poet who has not complete faith in the power of words. When I asked Ivaluardjuk about the power of words, he would smile shyly and answer that it was something no. one could explain; for the rest, he would refer me to the old magic song I had already learned, and which made all difficult things easy. Or to the magic words which had power to stop the bleeding from a wound: "This is blood, that flowed from a piece of wood".

His idea in citing this example was to show that the singer's faith in the power of words should be so enormous that he should be capable of believing that a piece of dry wood could bleed, could shed warm, red blood — wood, the driest thing there is.

— — —

Some poems are so fashioned that they can be reproduced without difficulty, almost word for word, as they are recited and sung. Such are the songs I have quoted here and there in the foregoing. But there are others which presuppose a thorough acquaintance with the events described or referred to, and would thus be untranslatable without commentaries that would altogether spoil the effect. This applies more especially to hunting songs, where the animals are not mentioned by name, bat indicated by some descriptive phrase, and where various details are explained beforehand, apart from the text proper, the latter being then often rather a kind of encouraging refrain, an incitement to the chorus, who, once in the grip of the tune, simply shout out the words among the other singers, and thus make the singing more pleasing and effective. In such cases, I have been obliged to seek explanatory information from the composers, who then interpreted the text for me into ordinary language, so that it was possible to translate it. I give here some examples of such songs, which would have been the merest guesswork in translation, if the poet himself had not furnished the needful commentary. All these songs are by Aua.

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tupaguatᴀrivuɳa

imᴀq man·a

sailᴇrata·talᴇrmät

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tautuɳ·uᴀrpäk·iga

nap·ᴀriᴀratatlᴀrmät

(aiwᴇq una)

kauligjuᴀq una

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tuɳnᴇriʃuɳᴀrivᴀra

tu·ᵛkaᵛnik

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tautuɳ·uᴀrpäk·iga

avatᴀra sᴇrqisᴀ·ratätlarmät

tautuɳ·uᴀrpäk·iga

ajäp·ᴇriᴀriätlarmät

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tulɔrsa·talᴇrmago

aksɔruku·tᴀ·rpᴀra

(awiɳakuluɳmik

pit·ɔrqutᴇqalᴀ·rmän)

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tᴀrqatigigamiuk ima

tuɳnᴇriʃuɳᴀrivᴀra

aɳuʷik·aᵛnikle·

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

anᴇrsᴀ·qᴀrpäm·ata

avaklivun piʒamiɳnik

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

This hunting song can however, be directly translated without comment beyond the two parenthetical passages inserted by Aua out of consideration for "the white men". The first of these passages merely indicates that the object of the chase was a walrus, which, he states, need not have been explained to his fellow-countrymen, as it would be apparent from the song itself. The second interpolation tells us that the amulet belonging to the hunting float was a lemming: this explanation likewise would be superfluous to an Eskimo audience, as a lemming is the regular amulet for hunting floats. The translation then runs as follows, save that the refrain ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja, incessantly repeated for the sake of the melody, and otherwise only chosen as easily vocalised words, is here omitted. These words alone however, can work up the chorus to full pitch when constantly repeated, and all can join in. And thus general participation, where everyone present can feel, as it were, a part of the song itself, is perhaps what makes it possible for a song festival to go on for many hours without anyone growing tired.

For the sea lay so smooth

near at hand.

So I rowed out,

and a walrus came up

close beside my kayak.

It was too near to throw,

And thrust the harpoon into its side,

and the hunting float bounded over the water.

But it kept coming up again

And set its flippers angrily

like elbows on the surface of the water,

trying to tear the hunting float to pieces.

In vain it spent its utmost strength,

for the skin of an unborn lemming

was sewn inside as a guardian amulet,

and when it drew back, blowing viciously,

to gather strength again,

I rowed up and stabbed it

With my lance.

And this I sing

because the men who dwell

south and north of us here

fill their breathing with self-praise.

The following song is typical of the indirect method, where the poet takes it for granted that the situation referred to is known in all its details, and therefore contents himself with throwing out a few words to the chorus, who then, steadily repeating a refrain, allow their own imagination to work on the theme. Anyone not familiar with the underlying idea of this poetic brevity would be quite unable to understand the meaning, and may then, like a wellknown whaling captain, otherwise fully acquainted with the language and customs of these people, form the impression that the text is a kind of poetic riddle-me-re.

nanɔralik

kiglimile·

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ᴇrsisa·ɳ·uäɳ·iɳmät

saɳuniᴀrniniuna

akuɳniɳin·ᴀriƀlugo

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

tᴀrqatigigamiɳa

tuɳnᴇrʃuɳᴀrivᴀra

aɳuʷik·aᵛnikle·

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja

ᴇrqasuɳᴀrsin·ᴀrpᴀra

anᴇrsᴀ·qᴀrpäm·ata

avaklivun.

Literally translated, the meaning is as follows:

one wearing the skin of a bear

out in the drifting pack ice.

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja.

It came not threateningly.

Turning about

was the only thing that seemed to hamper it.

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja.

It wore out its strength against me,

And I thrust my lance

into its body.

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja.

ajajaⁱja aja ajaⁱja.

I call this to mind

Merely because they are ever breathing self-praise.

Those neighbours of ours to the south and to the north.

I asked Aua to give me an explanation of the actual event which forms the theme of this song, and he told the story as follows:

He was out one day hunting walrus with his brother Ivaluardjuk, when they caught sight of a huge bear, a male. It came forward at once to attack them, running at full speed, looking delighted at the prospect of fresh meat, almost like a cheerful dog that comes running up at a gallop, wagging its tail. And so assured did it seem of the inferiority of its prey that it appeared quite annoyed at having to take the trouble of turning when Aua sprang aside. And now commenced a hunt that lasted the whole day. Ivaluardjuk had clambered up to a ridge of ice and was shouting at the top of his voice to frighten the bear away. So swift and fierce was the bear in its movements that Aua was unable to harpoon it, while Aua himself was so agile that the bear could not get at him. At last the great fat bear becane so exhausted that it sat down in the snow, growling like a little puppy in a nasty temper. Then Aua ran up and thrust his lance into its heart. Ivaluardjuk stood up on his ridge of ice a little distance from the scene of the combat and waved his arms delightedly. He was so hoarse with shouting that he could no longer speak.

This is the hunting episode of which the song treats. It has been related so often that Aua can make do with but the briefest reference in his text to the course of events. At my request, he filled in the gaps so as to give the action in full, the result being as follows:

nanɔralik

kiglimile·

ᴇrsisa·ɳ·uäɳ·iɳmät

qiɳmizut

unazutut paɳaliɳmaɳa

qilamik ᴀqajäktu·tigiumaƀluɳa

saɳuniᴀrniniuna

akuɳniɳin·ᴀriƀluƀlugo

pikʃilᴀ·rama

a·makitaujualᴀrpuguk

uvla·min uʷalimun

tᴀrquatigigamiɳa

uɳnᴇrisuɳᴀrivᴀra

aɳuʷik·amikle·

On the drifting ice,

It seemed like a harmless dog

That came running towards me gladly,

So eager was it to eat me up on the spot,

That it swung round angrily

when I swiftly sprang aside out of its way.

And now we played catch-as-catch can

From morning to late in the day.

But by then it was so wearied

It could do no more,

And thrust my lance into its side.

Another song was even more fragmentary, the text being spun out into incessant repetitions, with the customary refrain of ajaⁱja; in its original form, as Aua sang it for me the first time, it ran as follows:

misikʃaⁱgiga

ajajaⁱja aja

ajajaⁱja aja

natᴇrnᴀrmiutᴀq

ajajaⁱja aja

misikʃaⁱgigale

ajajaⁱja aja

pᴇraläktik·iga·

ajajaⁱja.

The heedless dweller of the plains,

All unexpected I came and took by surprise

The heedless dweller of the plains,

And I scattered the herd

In headlong flight.

— — —

I now begged Aua to give me the song in detail, and it then ran as follows:

With bow and arrows in my mouth.

The marsh was broad and the water icy cold,

And there was no cover to be seen.

Slowly I wriggled along,

Soaking wet, but crawling unseen

Up within range.

The caribou were feeding, carelessly nibbling the juicy moss,

Until my arrow stood quivering, deep

In the chest of the bull.

Then terror seized the heedless dwellers of the plain.

The herd scattered apace,

And trotting their fastest, were lost to sight

Behind sheltering hills.

— — —

Of course it is by no means all songs that are abbreviated in the text. It is done occasionally, because this also is reckoned something of a gift, to be able to convey the essence of a great event by the slightest indication. Finally, there is also the self-consciousness of the great hunter, underlying the view that one's adventures are so generally known that there is no need to describe them in detail. Accompanied by the weird rumble of the drum, one then flings out now and again, between repetitions of the stirring ajaⁱja, such simple words as:

The voice is raised and lowered in accord with the melody:

The dancer and singer suits the movements of his body to the steadily increasing force of the chorus:

And at last all believe they are themselves taking part in the happenings described.

— — —

I have already mentioned that the qaç·iʃut as a rule celebrated their festivals standing in a circle, with the men inside and the women outside, and in the middle the leading singer, called qilauʃᴀrtɔq: "the one that beats the drum". Sometimes, when the qaç·e is big enough," the participants will, especially among the Iglulingmiut, arrange themselves in such a fashion that the women kneel in a circle on the large raised platform of snow, while the men stand up out on the floor. The men awaiting their turn for dance and song stand innermost in the circle, nearest the one performing, who is called mumᴇrtɔq. Every wife must know her husband's songs, for the woman is supposed to be the man's memory. The mumᴇrtɔq will therefore often content himself with flinging out a few lines of the text, while his wife leads the chorus. A woman thus conducting the performance of her husband's productions is called iwɳᴇrtɔq: the chorus being termed iɳiɔrtut. A man without a wife, in other words, a singer with no one to take this important part, simply stands erect and sings his words. He is called iʷɳe·nᴀrtɔq: one who only sings. The nearest rendering of iʷɳᴇrpɔq is: utters his thoughts in song.

On the evening when any man of the village gives a banquet and festival in the qaç·e, the following cry is used to call the people together: "qaç·iava·, qaç·iava·", this is shouted about the place until all have heard.

Many remarkable customs are associated with song festivals in the qaç·e. I will give some further particulars of a few of the most characteristic, which, though known among the Aivilingmiut, belong more especially to the Iglulingmiut, where there are always many people together and an abundance of walrus meat.

There was the tivaju·t. When an ordinary qaç·e festival had taken place, and all those who so desired had sung their songs, the snow platform was pulled down and thrown out. Two men would then dress up, hidden from the inquisitive in one of the houses near by, one as a man, the other as a woman, and both wearing masks of skin. The idea was to make the masked figures appear as comical as possible. The woman's dress would be drawn in tight wherever it should ordinarily be loose and full, as for instance the large baggy kamiks, the big hood and the broad shoulder pieces; the dress in itself should also be too small. The same principle was observed in the case of the man's costume, which was barely large enough for him to get it on at all. The man dressed as a woman should have an anautᴀq, or snowbeating stick, in his hand, that is, a stick used for beating or brushing snow from one's garments; the male figure should carry a te·ᵍᴀrut, or short dog whip. Finally, the "man" should have fastened in the crutch a huge penis, grotesque in its effect, fashioned either of wood or of stuffed intestines.

In the middle of the qaç·e, from which the platform has now been removed, two blocks of snow are set out, one about the height of a man, the other half as high. These blocks should be roughly squared. The lower of the two snow pillars is called atᴇrᴀrtᴀrwik: the jumping block, the higher is called quᵈlᴇqᴀrwik: the lamp block.

As soon as the necessary preparations have been made, all the men and women assemble in the qaç·e, and now the two masked dancers, who are called tivaju·t, come bounding in. They are dumb performers, and may only endeavour to make themselves understood by signs, and only puff out breath between the lips and ejaculate "pust, pust" exactly as if they were trying to blow something out. They come bounding in, taking great leaps through the entrance hole, and must jump over the atᴇrᴀrtᴀrwik, this also to be done whenever they re-enter after an exit. The first thing the tivaju·t now do is to chase out all the men with blows, the woman striking with her anautᴀq, the man with his te·ᵍᴀrut, the women of the audience being suffered to remain behind. They then caper about, with light, adroit movements, among the women, peering everywhere to see if any man has concealed himself in their ranks. Should a man be so discovered, he is recklessly and mercilessly thrashed out of the house. As soon as the tivaju·t are sure all the men have gone, they themselves must dash out of the qaç·e, to where the men are assembled in a group outside. One of these men then steps up to the tivaju·t, and with his face close to the mask, whispers with a smile the name of the woman inside the qaç·e, with whom he wishes to lie the coming night. The two tivaju·t then at once rush back, gaily into the qaç·e, go up to the woman whose name has been whispered to them outside, and touch the soles of her feet with anautᴀq and te·ᵍᴀrut respectively. This is called ikuʃ·iʃut: the ones who hack out something for themselves with an axe or a big, sharp knife. Great rejoicing is now apparent among all the women, and the one woman chosen: ikut·aujɔq, goes out and comes in again with the man who has asked for her. Both are expected to look very serious; all the women in the qaç·e however, must be quite the reverse, laughing and joking and making fun, and trying all they can to make the couple laugh; should they succeed, however, it means a short life for the pair. The women in the qaç·e make faces, and murmur, in alle kinds of surprising tones: ununununununun, ununununun, ununununun! The two who are to lie together must then solemnly and slowly and without moving a muscle of their faces, walk round the lamp block twice, while the following song is sung:

ata·lune

kunige·cialaɳmᴀriga·

mamᴀri·cialaɳmᴀriga·

kisume·tɔq kan·a

a·t·ɔrtaile manᴇrmit·ɔq

kan·a a·t·ɔrtaile

tivajo· tivajo·, tivajo· tivajo·.

The words of this song are difficult to translate literally, but the following rather free rendering comes nearest to the sense as given by Orulo:

teasing, capering Dancer-in-a-mask,

Twist yourself round and kiss yourself behind,

you will find it very sweet.

Give him gifts,

dried moss for lamp wicks,

masquerader, masquerader,

teasing, capering Dancer-in-a-mask!

While this song is being sung, the two maskers stand facing each other and making all manner of lascivious and grotesque gestures; now and again the man strikes his great penis with his te·gᴀrut, and the woman strikes it with her anautᴀq, and then they pretend to effect a coition standing up. This is intended partly to demonstrate the joys of sexual intercourse, and partly also to elicit a laugh from the couple walking round the lamp block. The game is carried on throughout the evening, until all the men and woman have been paired off, the party then dispersing, each man leading home to his own house. the woman he has chosen.

Another favourite game was tɔrlɔrtut. When two song cousins met at a village, and one of them wished to challenge his iglɔq to a song contest, he would very secretly approach all the other men in the place, so that his iglɔq should have no idea of what was going on. Then in the evening, all would pretend to retire to rest as usual, but a watch would be kept over the house of the man to be challenged. As soon as it was known for certain that he was asleep, all the rest would get up, and, armed with their dog whips and snow beaters, steal up to his house and suddenly, with wild howlings and a terrible commotion, wake the sleeper by beating on the roof. This meant that there was to be a contest on the following evening in the qaç·e.

Another festival, only celebrated when there are many people, is called quluɳᴇrtut. It opens with a challenge between two iglɔre·k, first to all manner of contests out in the open, and ending with a song contest in the qaç·e. The two rivals, each with a knife, embrace and kiss each other as they meet. The women are then divided into two parties. One party has to sing a song, a long, long song which they keep on repeating; meantime, the other group stand with uplifted arms waving gulls' wings, the object being to see which side can hold out the longer. Here is a fragment of the song that is sung on this occasion:

gaily dressed in new fur garments,

women, women, youthful women.

See, with mittens on their hands,

gulls wings they are holding high,

and the long, loose-flapping coat tails

wave with every swaying motion.

Here are women, youthful women,

No mistaking when they stride

forth to meet the men awaiting

prize of victory in the contest.

The women of the losing party then had to "stride" over to the others, who surrounded them in a circle, when the men had to try to kiss them.

After this game an archery contest was held. A target was set up on a long pole, and the one who first made ten hits was counted the winner. Then came ball games and fierce boxing bouts. In these, it was permissible to soften the effect of the blows by wearing a fur mitten with the fur inside. The combatants had to strike each other first on the shoulders, then in the eyes or on the temples, and in spite of the glove, it was not unusual for a collarbone to be broken, or for a blow in the face to do serious damage. I have at any rate seen a man who had had one eye knocked out in the course of one of these tests of strength and manliness. After all these sporting events, which in the respective games required the two iglɔre·k to be unceasingly up to the mark and to show themselves at their very best, the conclusion took place in the qaç·e, where the two rivals had again to finish off their duel by a song contest lasting as a rule the whole night.

Apart from these festive customs more or less associated with the qaç·e, there were also the numerous kinds of games which, at any rate in the more cheerful villages, were practised not only by children but also by adults of all ages. Persons playing a game are called qitiktut.

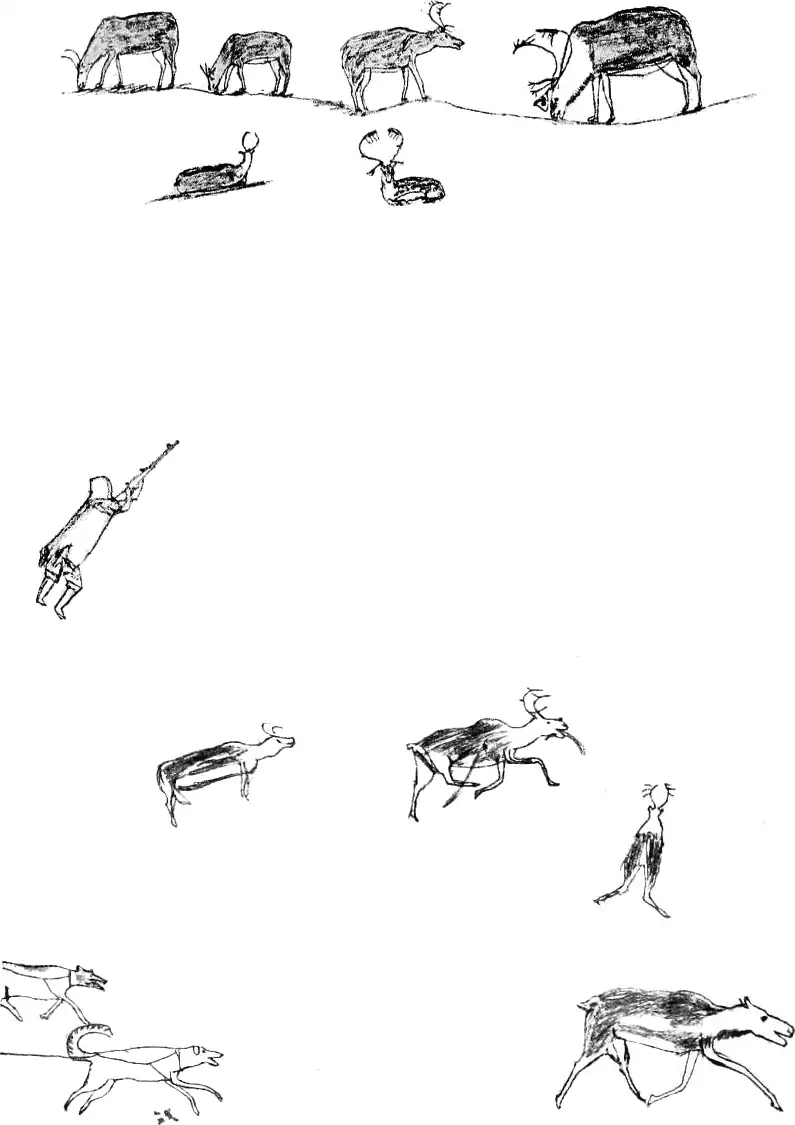

Greatly in favour were the gymnastic exercises with sealskin thongs stretched across the room, either in the qaç·e or in an ordinary dwelling. This was called akluɳᴇrtᴀrtut: those who played with thongs. The thongs were made fast by cutting holes through the wall of the snow hut and attaching the ends of the hide to sticks placed across outside. With these strips of hide, which were not very thick, and therefore cut into arms and legs with painful effect, exercises in strength and agility were performed, resembling in many ways our Reck exercises. I would here refer to Pakak's illustrations. which are an attempt at showing how these were carried out.

But then, besides all this, there were the real games. When the day's work was done, and the young hunters came home from their various expeditions, all those who were of a lively temperament would assemble out on the ice or on a piece of smooth ground behind the houses, if on land, and here the games would be played, preferably in the twilight or in the evening by moonlight. The following are some of the most common:

First, all form up in a long line and at a given signal run each to the place where he wishes to stand. The object is to pass a certain goal, a hole in the snow or a pole set up, or something of the sort: the one who is last to pass the spot has to be the wolf. The wolf has now to run after all the others, and every time he catches any one must touch him either on the neck or at the waist up under the tunic, but always on the bare skin; to touch the dress does not count. The moment the wolf touches one of the others he must say: uʷinigɔrᴀra: "I have touched his skin" and the one so touched is then wolf in his turn. And so the game goes on until all have been wolf.

This is often played by children. It is precisely the ordinary game as we know it, the object being merely for one to run after and touch another. In doing so, he cries "a·mak", and hence the name a·makitaujuᴀrnᴇq, which means "to say a·mak to one another".

There is also a ball game in which the players endeavour to run certain marked distances set out in a square, with stops only allowed at the corners, a kind of rounders. There are two sides, one first throwing the ball to one of the other side, who strikes at it with a kind of bat. Having struck the ball, the striker has to run from one place of safety to another without being hit; thus one player after another runs in turn. As soon as one of a side is hit by one of the other, they change over, the batting side handing the bat to the others.

The players divide into two sides, which, however, do not form up in separate groups, but mingle together. One side has the ball, and throws to those of the same side, the other players trying to take the ball from them. At every throw, there is a wild scrimmage, the object all through being for one side to get the ball from the other.

One of the players hides, and the others look for him. As soon as the one in hiding is found, all must run after him, and the first to touch him is the next to hide. When one has gone into hiding, the rest cry: "ilak kuk·umiᴀrit": "comrade, utter a sound". The one in hiding must then whistle, and should as often as possible change his hiding place and whistle again, so as to deceive the others as to his position.

Children find a small piece of wood and make of it a little sledge: then all their companions come and are harnessed to it, or more correctly, pretend to be harnessed. The boy on the sledge then pretends to whip his dogs. This is called: Driving the sledge.

Children select a small hill and slide down it on a skin, a piece of sealskin or caribou skin. If the hill is steep enough, they simply lie flat face downwards, and slide down in the furs they are wearing.

This game is played with a ball, the player striking it up in the air again and again with one hand. The player who can keep this up for the greatest number of times without letting the ball fall to the ground is the winner, and receives a prize from the rest.

A child runs in to the passage way of a house, and while there, is beaten about the body by one of the others with clenched fist. The one thus beaten must then begin to run after the others. Some run into the house to escape, others run out, and the object now is to catch them in the same way as in the wolf game, by touching them on the bare body. Every time the pursuer touches one of the others, he must say "uɳa·", and at last, when he has touched every one, another takes his place and the game begins anew.

Children form up in a long line. The one who is to be moon takes another player, and the pair place themselves a little distance from the rest. Some of those in the line now move off, pretending to search for fuel. As they pass by the one playing moon, they must pretend not to see him, and try to carry off the child. When the latter resists, they must cry out: "ana·luk, ana·luk" (an excrement). When they then add: "A piece of caribou suet, a piece of caribou suet" the child consents, and goes off with them. Thus they take the child with them, and hide it behind those in the line. The moon now suddenly discovers that its child is gone, and must then say: "But where is my child gone?"

He goes off in search of the child, and must pick up all the pieces of dogs' dirt he sees on the ground and rub them over his belly and hindquarters, then smell them and throw them away, and leaping high in the air, exclaim once more: "But where is my child gone?"

Then he comes up to those in the line, and sniffing at them, says: "Of course he has been enticed away with caribou suet and dainty eyes and tongue. What did you have it in?"

"A piece of a mitten."

"What did he use for a knife?"

"A piece of flint."

The one playing moon must now strike those in the line, tread on their feet and kick at them, saying:

"What is it making all that noise over there?"

Then those in the line answer: "Dogs."

And then they all begin saying "miam, miam, miam" and pretending to eat the child. The one playing moon now asks the child: "Who was the first one that took you?" And the child answers: "That one there". And now the moon begins to go for the others in earnest, trying to frighten them, and every time he gets hold of one, tickles him and ill-treats him as hard as he can. The game ends when he has gone the whole way round.

A party of children join hands and form up in a circle, crying: "ᴀ·ʀa·," repeating it again and again. When they have stood thus for a time, one of the players attempts to break out of the circle, the rest doing all they can to prevent it. If one succeeds in breaking away, he must run over to two other children, standing some distance from the group, hand in hand, and try to force himself in between these two; should he succeed, one of the pair thus divided must strike him, saying: "umiᴀq" a skin boat, and after a pause, adding: "May you have the strength of a wolverine!"

The next time one comes up to the pair standing hand in hand a little way from the group, the same process is repeated. They must say "umiᴀq" to the one who joins their group, but this time, after striking him, they must add: "May you have the strength of a wolf." And so the game goes on, with wolf and wolverine alternately. When this has gone all round, wolves and wolverines fight, two and two but the pair that stood holding hands, and named the others wolf and wolverine respectively, are now themselves called grandmothers, and must cry out: "Wolverines, use your strength, wolves, use your strength." They now fight and keep on until one side wins.

A piece of caribou skin is filled with all manner of articles, giving it the shape of a big ball, and sewn up; it is then played with as follows:

The players take sides, with the passage way of a house for goal on either side. The side that kicks the ball into the other's goal wins. Next day the game is resumed, the losers of the day before endeavouring to make matters even.

The players are assembled in the qaç·e, and the one to be blindfolded is given a blow to start off with. He must then at once close his eyes so that he can see nothing, and then endeavour to touch the others; on touching anyone, he strikes him in the same way as he himself was struck at first and may then open his eyes. The player caught must then be blind man, and so the game goes on.

Two players take a sealhide thong, one holding each end, and swing it, a third trying to jump over and under.

An inflated sealing float is used for this, with a line attached at either end, and swung round in the same way as the skipping rope, the players trying to jump over and under.

The player collects the knuckle bones from the flippers of a seal, shakes them in one hand and drops them. Each bone is named after a man, and the man whose name-bones stand on end when thrown will be lucky in hunting.

A mug or dipper with a handle, such as is used for water, is taken and twirled round, the players sitting about in a circle. The one to whom the handle points when it stops must hand out some article belonging to him. Next time the handle points, the player indicated. picks up the article deposited by the first, forfeiting something of his own instead. And so the game goes on.

A piece of bone with a small hole in it is hung from the roof and swung backwards and forwards. Each player has a thin stick and tries to thrust it into the hole as the bone passes before him. The first to do so must pay a forfeit, which is claimed by the next to succeed, and so on as in the previous game.

The player takes two, three or four pebbles, and juggles with them, singing the following song:

tun·it tun·it tun·e·t

ajaⁱjᴀrujuɳ·ne· ajaⁱjᴀrujuɳ·ne·

kam·aɳ-ukua put·atlᴀrtᴇrute·ɳ

auɳmiɳ tᴀrtautiʲuɳ, tᴀrtalat·iuɳ

alᴇqämauna siuʷaliut,

anᴀrnicualukʒuaq

uʷa·tale uʷa·tale uʷa·tale

alᴇqäciᴀra piɳasuniɳ

uʷaɳale ataucimiɳ

kak·e·k·ak najɔrtuᴀriʷak·ak

imᴇrpak·a, imᴇrpak·a ajai ajai

kitutle aɳagigaluᴀrpagit?

a·ⁱjaⁱlu·t·ik·ut qatlᴀrialinik·ut

nigäƀjulik·ut te·ᵍᴀrutik·ut

sun·iala·k·ut nuʷuk·ut

ajija· aja·ja· ajija aja!

The text is incoherent and almost untranslatable. It is recited or sung very rapidly, to make the juggling more difficult; I give here the untranslatable portions in the original, and a literal rendering of the remainder:

Tattoo marks, tattoo marks, tattoo marks

— Little children, little children —

They make one's anger overflow,

They make the blood swell in the veins,

My elder sister was the first,

A big one that smelt of dirt,

uwa·tale uʷa·tale uʷa·tale

My little elder sister had three

I had one,

my elder sister two

I one,

I sniffed up the dirt from my nose and swallowed it,

I drank it, I drank it, ajai, ajai.

Whore are your mother's brothers?

Are they a·ⁱjalu·te or qatlᴀrianilik?

Are they nigäƀjulik or te·gᴀrut?

Are they sun·ialᴀ·q or nuʷuk?

ajija· aja·ja· ajija aja!

Two little girls jump up and down keeping time together, and sing:

a·jäɳaja·jäɳaja·jäɳaja·

tukliliutik·ik qailak it

ᴀrnᴀqatiʃautiginiᴀrapkit

a·jäɳaja·-a a·jäɳaja·-a

a·jäɳaja·jäɳaja·jäɳaja·

I will deck myself with it,

To make me look like a real woman,

a·jäɳaja·-a

etc.

This song also is sung very rapidly, the singers jumping up and down and bending the knees to the full each time.

These are briefly the games specially played by children and women. In good seasons, when game is plentiful and parties remain for a long time at one place, the women will, unlike the men, have very little exercise, and it is therefore not a mere coincidence that nearly all the games include some form of gymnastic activity. Thus nature regulates itself at all times, and the people keep themselves in health and good spirits by means of pastimes which in a pleasant and festive manner fill the space about the houses with merry cries and laughter.

There is also an Eskimo proverb which says that those who know how to play can easily leap over the adversities of life. And one who can sing and laugh never brews mischief.