Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos/Chapter 1

Eskimo Life: Descriptions and Autobiographies.

Our first encounter with these natives took place on the 4th of December 1921. More than two months had passed since our arrival at Danish Island, and up to now we had not set eyes on a single human being of the tribes we had come all this way to visit. Work of various kinds had kept us busy at headquarters, and the state of the ice had hitherto precluded excursions of any length. By the end of November, however, all the fjords were frozen hard enough for us to set out for Repulse Bay, where we knew there should be one of the Hudson Bay Company's trading stations. We could there obtain information as to the distribution of the population between Iglulik and Chesterfield Inlet.

Peter Freuchen, the Polar Eskimo Nasaitsordluarssuk and I were at last on our way to the north-west in search of natives. We had followed the northern coast of Vansittart Island through the mouth of Gore Bay, and making a wide detour where the strength of the current prevented the formation of winter ice, had gone overland. past the south-western coast of Melville Peninsula; we were now on the sea ice in Haviland Bay. We had had an accident to one of the sledges, which had suffered damage among the pressure ridges, and Freuchen and Nasaitsordluarssuk were consequently a little way behind.

It was about noon, the red of the sun tinged the horizon out towards Rowe's Welcome. The sky was perfectly clear, and it was bitterly cold. A faint breeze blowing right in my face stung so that I could hardly keep my head to the front as I drove. It was fine, level fjord ice underfoot; we were some distance from the edge of the ice, which was just visible with its pressure ridges to the south, and as the way was clear ahead, I had turned my back to the wind for a moment, to thaw my face. I had only been sitting like this for a moment, when I started up at a sudden sound. I had heard it quite distinctly, and the dogs too must have noticed; they began to sniff eagerly about, and I was thus sure I had made no mistake. The sound I had heard was that of a shot fired not far off; there was no mistaking it. I glanced back towards my companions, thinking they had fired as a signal to me to wait. I soon descried them, but they were driving up at a good pace, and as far as I could see, overtaking me; it could not be from them. I then looked out ahead, and perceived, some four kilometres distant, a black line extending across the ice midway out in the bay. It could not be bare rock. I stopped the team at once and got out my glass; and now I could plainly distinguish a whole line of sledges with a great number of dogs. They had halted, as I myself had done, and were watching me intently. One man broke away from the rest, and came running across the ice at right angles to the line I was following. I realised that he was making for me, and with the excitement natural to a first meeting with human beings in these wilds, I at once jumped on the sledge and gave my dogs the signal for full speed. It was not long before they too sighted the man as he ran, and regarding him as game in flight, set off in chase. In a few minutes I had come up with him, and the dogs, themselves excited by the strange smell of him, and his unfamiliar dress, would have attacked him had I not shouted to him to stand still. I stopped the team at the same moment, cracked my whip over their heads, and leaped clear of the sledge in front of the dogs, so as to place myself between them and the stranger. I had made a long jump, and with such impetus that to avoid knocking him over I was obliged to throw my arms round his neck. So there we stood, laughing and shaking each other, while the dogs, crestfallen, lay down on the ice, as if ashamed at having mistaken a friend for an enemy.

The first thing that struck me when I had recovered a little was that the man understood all I said; and I understood him in turn when he spoke. He was a tall, well-built fellow, his face and long hair covered with rime after his run, which had made him so hot that his cheeks were literally steaming. He explained that his name. was Papik ("Tail feather") and he had his autumn quarters by Nivfâvik, which I later ascertained was up at the head of Lyon Inlet. I was so eager to get into touch with the natives that I did not wait for my companions to come up, but went across at once to the group, now quite near. The men came forward to meet us without hesitation, but the women and children remained lying by the sledges, stretched. at their ease in the sun, as if there were no such thing as cold. Several of the women were nursing half-naked infants at the breast. The light fell on their brown smiling faces, and my first impression was that they must be uncommonly hardy folk. I considered myself fairly accustomed to the climate of these latitudes, but only a moment ago I had suffered so from the icy wind that I had been forced to turn and let my face thaw. Yet here were these women and children sitting about as if altogether unaffected by the cold.

These, then, were the people whom the Greenlanders called Akilinermiut ("those who dwell in the land beyond the great sea"); the people I had heard about ever since, as a boy, I had first begun to listen to the Eskimo folk tales. I could not have found a more picturesque setting for a first impression. Here was a whole caravan out in the midst of the ice, men and women in curious dresses of skins, like living illustrations to the Greenland story-tellers' tales of the terrible. "inland folk". Every stitch of their clothing was of caribou skin, fine. short-haired skins of animals killed at the opening of the autumn hunting season. The dresses of the women especially rendered them altogether shapeless — very wide in the upper part, with a big fur hood falling from the shoulders down over the back, and long loose coat tails coming down over the breeches before and behind, edged with white skin. The footwear also was peculiar, the actual boots. being apparently covered with an outer envelope, commencing in a long tongue right up on the thigh, and terminating just below the calf in a sort of bag; a most comical arrangement, serving as far as could be seen no useful purpose whatever.

The curious fur dresses of the men were as if made for running: they were not so long as those of the women, but had the same tail fashioning front and back. The tails were either of equal length, divided up the thigh, or comparatively short in front with a longer tail behind.

Many different impressions passed rapidly through my mind at this first meeting, but there was one thing which moved me beyond. all else, and almost at once made a bond between us, as if we had been old acquaintances, and that was the language. True, I had always known that the natives here spoke the same tongue, but I had never imagined there would be so little difference that we could enter into converse at once without the slightest hindrance. Owing to the similarity of language, they took us at first for distant tribal kinsmen from Baffin Land. They themselves had just started off with their loads on the sledges, on the way to their snow huts a few days' journey away. But like all Eskimos, they were so swayed by the impulse of the moment that all thought of proceeding on their way was abandoned for the present. As soon as they saw we were friendly folk, as interesting to them as they were to us, they went wild with delight. There was a shouting and laughing and cracking of jokes which further raised their spirits, and as there happened to be some big deep snowdrifts close at hand, we moved over to them at once to set about building snow huts, where we could spend the rest of the day and the night in improving our acquaintance and celebrating the occasion. This frank, spontaneous friendliness was a great pleasure to me, for I realised that among such people I should find no difficulty in learning from them, later on, all they could tell about themselves and their past.

Meeting an unknown tribe is rather like travelling through unknown country; one is, so to speak, prepared for surprises. And so it was with us. The surprises were not wanting. The faculty of observation is of course most alert at the first meeting. The common, everyday business of building a snow hut, which we ourselves had had to do hundreds of times, was now something extraordinary; and quite exciting to watch. Never had we seen a house spring up so rapidly out of the snow as under the snow-knives of our new friends here. Among the Polar Eskimos of North Greenland, the building of a fair-sized snow hut is reckoned a good hour's work for two men. One cuts the blocks from a snowdrift lying outside the ground plan of the house, and hands them, unless there happens to be a third man on the job, to the one who is building the hut. Here however, one man cut the blocks and built the hut at the same time. Selecting a portion of a snowdrift where the snow was of the right degree of firmness for his purpose, he marked out a circle in it, the snow. within the circle being reckoned to suffice for the entire hut. To make a calculation of this sort in a moment calls for a great deal of experience and practice. Actually, then, our native architect here builds. his wall and the selfsupporting roof up over the space left by the blocks cut out of the drift as he works. He must therefore cut down to the full depth of the drift, working his way to the bottom, whereas the Greenlanders cut the blocks they need from the surface. It was a simplification of the process amounting to genius, and labour-saving to such a degree that one man here could cut the blocks, set them in place and trim them off with his knife all in about the same time that a Greenlander would take to cut the blocks alone. As the hut grew up out of the drift, one of the women, taking a big flat wooden shovel, spread loose snow over the wall from the outside. This layer of loose snow fills in any cracks and crevices, making the house. thoroughly sound and warm inside, however hard it may be blowing without. The remarkable skill here displayed was evidently the result. of many generations' technical experience, and we at once realised that we had come upon a system of winter housing, and a capacity for utilising available material, superior to that which we knew from Greenland. These men were experts in the use of snow as building material. In three quarters of an hour, three large snow huts were ready; and almost as soon as the snow bench inside was cut to shape, the blubber lamp was lit and the interior warmed up. I and my two companions quartered ourselves in different huts, so that we might make the most of our new acquaintance. Before long, all our baggage was stowed on high platforms built of oblong snow blocks, and as soon as the dogs had been fed, we could go in and settle down among our friends. Snow was melted in pots hung over the lamp, and our hosts boiled caribou meat from the store they had with them. We had walrus meat, but were not allowed to cook any, as this was strictly taboo in a house where caribou meat was to be eaten at this time of year.

My host was a genial, kindly fellow named Pilakapsak; his wife Hauna was untiring in her efforts to make us comfortable, and it was not until all had eaten their fill that we settled down to talk.

We now learned, to our great satisfaction, that there were native settlements in nearly all directions from our headquarters on Danish Island. The population was not overwhelming in numbers, but the more interesting in point of composition. A couple of days' journey from our house we could come into contact not only with Iglulingmiut, but also with Aivilingmiut and Netsilingmiut.

The conversation was of a very general character, we on our part feeling our way carefully at first, to learn how far we could go in our questionings without appearing too inquisitive. Thanks to our speaking the language, however, and the confidence this inspired in our hosts, we were able even to touch upon matters of religion, in regard to which I very soon ascertained that these people were still entirely primitive in their views and unaffected by outside influences.

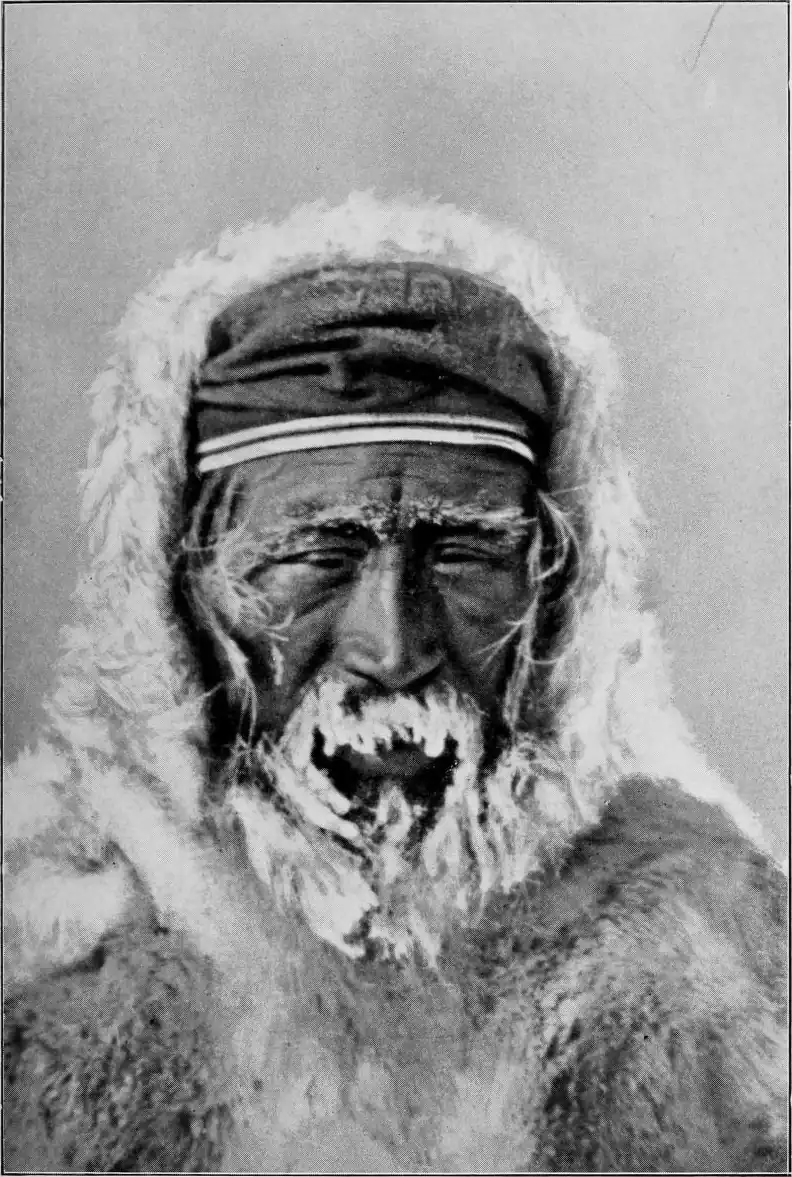

On the day following this first meeting, we arrived at Repulse Bay while it was still daylight, and made the acquaintance here of Captain George Cleveland, an old whaling captain, now in charge of the Hudson's Bay Company's trading station there. Captain Cleveland received us with great hospitality, and most willingly furnished us with a great deal of information that proved very valuable in arranging our plans of work. We stayed here a few days, and made several other acquaintances, including that of one old man in particular with whom I was to have further dealings in the course of my work later on. His name was Ivaluardjuk; he had a long white beard and red, rheumy eyes, worn dim with over many blizzards. He was, it appeared, the geographer of his tribe, and was remarkably well up in the country and its inhabitants throughout the entire range between, Ponds Inlet and Chesterfield. When I brought out a pencil and paper, he drew, to my astonishment, the whole coastline from Repulse Bay to Ponds Inlet, without hesitation, and though the proportions of course could not be correct, the map yet gave such a good general view that we were now able to fix a number of the Eskimo placenames. This was a very essential point for us, as we should have to discuss the various localities with natives who knew nothing of the English names given to parts of their own territory by Parry and Lyon a hundred years before, while on the other hand they had an abundance of names of their own for fjords, lakes, mountains and all characteristic features. I was thus able to note, on the map drawn for me by Ivaluardjuk, somewhere about a hundred Eskimo names, which I shall refer to later on.

I discovered at once, in the course of our first talk, that Ivaluardjuk, though very careful about what he said, was remarkably well acquainted with the ancient traditions of his tribe. In order to draw him out a little, I narrated a few of the stories common in Greenland. These proved to be well-known here, and the surprise of the natives at finding a stranger from unknown lands able to relate old tales they fancied were exclusively their own, was such that in a short time the house was filled with inquisitive listeners. Thus I gained the old man's confidence, and we were soon discussing the folk-lore of his people as experts, the reserve he had shown at first being gradually discarded. He is the oldest member of the household I am visiting, and is indeed one of the oldest members of his tribe. He himself might have stepped out of some old, weird story, with his strange, worn look, and the quiet, steady manner of his own narration makes a deep impression on those around. After a while he tells me something of his own family affairs. He ought long since to have been a widower, he says, a poor old fellow with no authority among his neighbours; for his first wife had died many years before, and all his children of that marriage grown up. But he dreaded the loneliness and helplessness that are always the lot of a wifeless man in his country, and had therefore married an adoptive daughter of his own, and bought her a child, paying for it with one of his dogs. He laughs in his quiet, kindly fashion as he tells the story, and adds:

"Thus men can better their existence and soften the harshness of fate. Now I no longer feel alone, and my old age is a restful time. But when chance to think of my childhood and recall all the old memories from those days, then youth seems a time when all meat was juicy and tender, and no game too swift for a hunter. When I was young, every day was as a beginning of some new thing, and every evening ended with the glow of the next day's dawn. Now, I have only the old stories and songs to fall back upon, the songs that I sang myself in the days when I delighted to challenge my comrades to a song-contest in the feasting house".

Hardly had he finished speaking when all present begged him to sing a song; he made no objection, but drew back a little on the bench. His wife then chanted in a clear voice a monotonous air, consisting of but a few notes constantly repeated. The other women at once joined in, and Ivaluardjuk himself, thus supported, delivered a peculiar song which I afterwards wrote down. The ideas and expressions, and the general effect, of Eskimo songs are so unlike anything we are accustomed to in our own that it is not always possible to translate literally. The following is, however, as close a rendering of the original as can reasonably be given when endeavouring at the same time to reproduce something of the charm and the unconscious art displayed in the utterance of the Eskimo singer:

These two pests

Come never together.

I lay me down on the ice,

Lay me down on the snow and ice,

Till my teeth fall chattering.

It is I.

Aja — aja — ja.

From those days,

From those days,

Mosquitoes swarming

From those days,

The cold is bitter,

The mind grows dizzy

As I stretch my limbs

Out on the ice.

It is I,

Aja — aja — ja.

Call for strength

And I seek after words,

I, aja — aja — ja.

Something to sing of,

The caribou with the spreading antlers!

The spear with my throwing stick (sic!).

And my weapon fixed the bull

In the hollow of the groin.

And it quivered with the wound.

Till it dropped

And was still.

Call for strength.

And I seek after words.

It is I.

Aja, aja — haja — haja.

This utterance of an old man, who recognised that for him the joyous days of life were long since over and past, brought the noisy listeners to silence. And I saw that these people I had come to study were not unacquainted with the virtues of piety and reverence. I realised that if I could only go the right way to work, I could learn from them something that might show others at home something of the Eskimo mind.

My visit to Repulse Bay proved of the greatest importance in the subsequent arrangement of my work. The natives here were frank and genial folk, with whom it was easy to enter into conversation on ordinary matters of everyday life. Nor had they any reluctance to tell a story, or sing a song accompanied by the whole household as chorus. But as soon as I ventured to touch on more serious themes, they showed more reserve. There were great and difficult questions here which were best left alone. Only when actual happenings called for some decision, some course of action in face of threatening circumstances, would the subject be discussed with the wise men of the tribe. The earth grew angry if men out hunting worked too much with stones and turf in the building of their meat stores and hunting depots: so also the spirits that guided men's fate might be offended if men concerned themselves over much with such things. Men knew so little of things apart from their food and sleep and rest; it might easily seem presumptuous if they endeavoured to form any opinion about hidden things. Happy folk should not worry themselves by thinking.

And old Ivaluardjuk held to this view at first, maintaining a profound reserve when I endeavoured to draw him out. Moreover, apart from this innate reluctance to speak of such things as life itself and the purpose of life, and its guiding powers, the Eskimos of these regions were extremely cautious in expressing their views at all when dealing with white men. True, no missionaries ever came here — save for a few brief visits — to condemn their religion, but the little they knew of "that sort of white men", who were so unlike the traders and whalers, was not calculated to render them more communicative. As far as they could understand, it seemed that the strangers regarded them pityingly on account of their belief in such unreasonable things as their wise men maintained to be the foundations of all wisdom. A kind of spiritual shyness, not unmixed perhaps with a certain sense of dignity, made them reticent on the subject: they merely acknowledged that the missionaries otherwise appeared to be good men in their daily life.

"The other sort" of white men comprised the traders and whalers. These were bright, smart fellows, caring only for their hunting and trading. But when any of them occasionally happened to be present at the solemn seances of the angákut, they would merely shrug their shoulders, or make some scornful remark, as to the relations of these shamans with the supernatural. Furthermore, all white men looked with supreme disdain on the system of taboo by which the balance of the Eskimo community was maintained.

I understood then, that if I were to succeed in gaining the full confidence of these people, it was absolutely necessary to place myself in their position. I was not concerned to guide or correct them in any way, but had come to their country expressly for the purpose of learning what they could teach. The thing to do, then, was to make friends with some of the elders, those most familiar with the traditions of the tribe. Once I had won their friendship, the rest would come of itself.

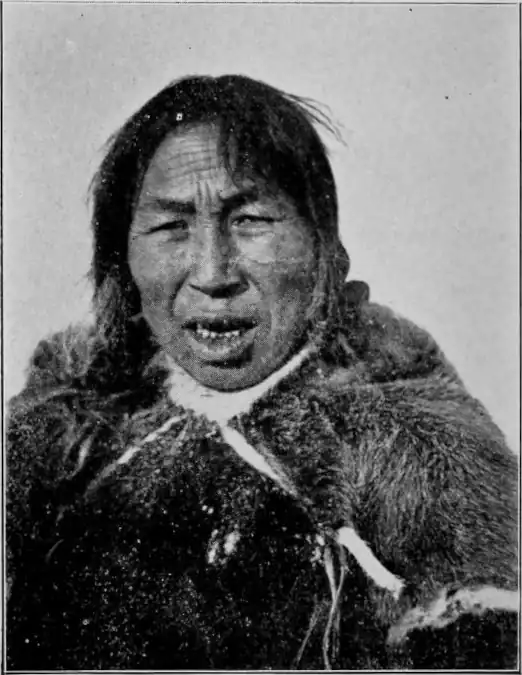

It was not long before I made just the sort of acquaintance I had in mind; it happened indeed on the way back from Repulse Bay to Danish Island. Peter Freuchen had gone on further south to continue his investigations, and Nasaitsordluarssuk and I were driving home alone to inform our companions of all that we had learned. In order to save time, we decided to make a short cut from Haviland Bay down to Gore Bay. We had not got far inland when we came upon an old woman fishing for trout in a lake. The ice was thick already, and she lay half hidden among broken hummocks, with her head bent over the hole where her line was down. We thus took her entirely by surprise. She started up as the dogs gave tongue, and stumbled backward in confusion at the sight of us. We had already been told that the natives here were not usually pleased to encounter strangers unawares; there was no knowing whether it was friend or enemy. We were not surprised then, that the old woman endeavoured to run away: in this, however, she was unsuccessful: in fact, a moment after she was sitting on my sledge — albeit much against her will — and driving down towards the place where she lived, our dogs having already scented human dwellings near. She had with her at little puppy, that she had not wished to leave behind, and held it in her lap with a convulsive clasp, looking up at me at the same time with such an expression of terror in her eyes that I could not help laughing. She had heard nothing of our arrival in the district and saw now only two men and two sledges, every detail revealing the stranger. The fashion of our clothes, the build of our sledges, the dogs' harness, and even our manner of speech. She was sitting behind me, and as I bent down to explain who we were and what we wanted, I suddenly noticed a sound I had not perceived before, and now discovered, tucked away down at the back of her behind the fur hood, a little naked infant with its arms round her neck, squealing in concert with the puppy. I now hastened to mention the names of all the new friends I had made during my stay at Repulse Bay, and this, as showing that I was well known to people she knew as neighbours, changed her attitude entirely. So delighted was she to find herself among friends that her eyes filled with tears. As soon as she had calmed down a little, I explained where we had come from. It was easier now to do so than in the case of our first meeting with natives at Haviland Bay, for I could now give the Eskimo names of the places. I knew that Ponds Inlet was called Tununeq, and explained therefore that we came from a country beyond the great sea that washed the shores of Baffin Land. Hardly had I finished. speaking when she told me that she herself was called Takornâq ("the recluse" or "the one that is shy of strangers") and came from Iglulik. She had moved down to Repulse Bay with her husband, Padloq, expressly in order to be near white men and all the wealth which one could obtain by bartering with them. She had often been to Ponds Inlet, and had met Scottish whalers there. They had told her of the people from whose land we came, who spoke the same language as she did, and lived over on the other side. So pleased was she at finding that we belonged, as it were, to her own world after all, that she became frankly communicative, not to say garrulous herself. It was not long before we had the village in sight and soon came up to the three snow huts which were all it amounted to. They were built close to a lake where trout were to be caught. The inhabitants came running towards us but without knowing quite how to receive us, for they also had recognised at once that we were strangers. But on catching sight of Takornâq, who was laughing delightedly, they came up and gathered round us. Takornâq certainly did not bear out the character implied in her name. She chattered away, recounting all the information she had just acquired, and pointing to us, explained that we were real live human beings, from a country far, far away beyond the sea from Tununeq.

Takornâq was consious of her position at the moment, as the principal actor in the scene, and when I asked her the names of those about us, she took me by the shoulder and led me, laughing herself all the time, from one to another, mentioning their names. This one was Inernerunashuaq ("the one that was made in a hurry") an old shaman, and I noticed that he wore, as a mark of his dignity, the belt of office round his waist, consisting of a broad strip of skin hung about with many odd items, bones of animals, little implements, knives and whips cut out of walrus ivory. His wife, who was conspicuously tattooed on the face, was called Tûglik ("northern diver"), a big, fat woman with a whole crowd of little children hanging to her skirts. Then there was Talerortalik ("the one with the forepaws"); his wife was the shaman's daugter, Utsukitsoq ("the narrow vulva"). The young couple stood modestly in the background, but Takornâq, who was not afraid of saying what she thought, declared openly that it was they who kept the shaman and his family alive. Inernerunashuaq might be a great shaman — that was none of her business to say, she put in laughing — but he was certainly a very poor hunter. This lack of respect for a shaman interested me very much, albeit the remark was only made in jest, for I had always understood that the natives were very careful about what they said to the shaman. I learned afterwards that this was indeed the rule, and Takornâq the exception, being not only remarkably free with her tongue, but equally sincere in what she said. She was herself skilled in shamanism, though practising more in secret, and would thus know something of the limitations of the craft. Finally, there was Talerortalik's brother Peqingajoq ("the crooked one"), who was actually a cripple, with a pronounced hunchback figure. Takornâq informed me that he was a most hardworking fellow, and so keen on his fishing that there was always ice on the front of his dress — from lying face downward on the ice at his fishing hole. There were other natives in the party, but it would take up too much space to mention every one.

Takornâq, maintaining that she had a sort of right to us, as having been the first to meet us, now invited us in to her house. It was a well-kept snow hut, but rather cold until we got the blubber lamp going. Nasaitsordluarssuk and I clambered up on to the bench, which was completely covered with warm skins of caribou, a pot of meat was set to boil, and these domestic preparations finished, our hostess sat down between us and declared that now she was married to both of us, for her husband was away on a journey. She burst out laughing herself at this observation, and seemed to enjoy her own joke immensely. It was indeed, not to be understood in any ill sense, for she added directly after that she knew no better man than her husband. It was only her fun, she said, and there was no harm in talking nonsense when one felt a little jolly.

As soon as the place was warmed up a little, she pulled out the infant from her amaut, and laid it with motherly pride in a sleeping bag of hare's skin. The child's name was Qahîtsoq, it had been called after a mountain spirit. It was not her own child but one of twins, belonging to a certain Nagjuk ("deer's horn") of the Netsilingmiut, and Takornâq had bought it of him as it would otherwise have been killed. "Twins", she added, "are hardly ever allowed to live in our country, for we are always travelling about, and a mother cannot carry more than one in her amaut". The price paid for Qahîtsoq was a dog and a frying pan; really too much for such a skinny little bit of a thing. Takornâq was evidently sore at the recollection that Nagjuk had cheated her, and kept the fatter of the twins for himself.

Takornâq talked incessantly, and it was not long before we were quite like old acquaintances. There was no need for me to say much, a grunt here and there, an encouraging remark, sufficed to keep her going. She was proud of her descent, for the Iglulingmiut, which of all the tribes has had least to do with white men, is reckoned as having the cleverest hunters and the best women. She was therefore anxious that we should not mistake her birthplace for that of the others in the village, these being all Netsilingmiut. They were dirty with their clothes, she said, and not at all clean in their houses. She and her husband, now, had special vessels for urinals indoors, which showed how cleanly they were even when living in snow huts, whereas the Netsilingmiut did not hesitate to make water on the floor, or even on the bench under their pillows, simply lifting up the skins that covered it.

When the talk began to quieten down a little, I told her about my own childhood in Greenland, that she might understand how I came to speak her language, and having ended my story, I declared that I would rather listen to others than talk myself. At this she burst out laughing, and observed that it was just the other way with her: she would much rather talk herself than listen to other people. I therefore took her at her word and begged her to tell me about her own life, as far as she could remember, from her earliest childhood. And now for the first time since we had entered the hut, Takornâq seemed inclined to talk seriously. She closed her eyes and sat for a long time without speaking; then when at last she began, she gave us the whole story of her life, all her experiences recounted without hesitation, in clear and fluent language.

"My father and mother often had children that died. My father was a great shaman, and as he was very anxious to have children, he went up inland to an ice loon and asked it to help him. My father and mother say that it was with the aid of this creature that I was born; a strange creature it was, half bird, half human. So it was that I came into the world. And I lived.

"Some time after I was born, there came a season of scarcity, and all were in want of food. My father had gone out to a hole in the ice, and here, it is said, he spoke as follows:

"'If my daughter is to live, you will remain as you are. If my daughter is to die, you will close over, and keep away all the seal. Now give me this sign.'

"The hole in the ice did not change, there was no movement in the water, and my father began to catch seals, and he knew that I was not to die.

"When he came home in the evening, he said to my mother:

"'Today a sign has been given to tell me that our daughter is not to die like the others. Therefore you need no longer trouble about all those rules for women who have had a child.'

"And though it is the custom among our people for women with young children to refrain from many kinds of food which are considered harmful to the child, my mother now ate whatever she liked, and nothing was forbidden to her. But then it came about that I fell ill after all, and they thought I should die. Then my father said to my mother:

"'Take the meat fork and stand it up in the pot! If it falls down she will die; if it stays upright she will live.'

"The fork was laid across the pot, and slipped down of its own accord and stood upright. Thus once more they learned that I was to live, and my mother again took to eating whatever she liked.

"Thus I began to live my life, and I reached the age when one is sometimes as it were awake, and sometimes as if asleep. I could begin to remember and forget.

"One day I remember I saw a party of children out at play, and wanted to run out at once and play with them. But my father, who understood hidden things, perceived that I was playing with the souls of my dead brothers and sisters. He was afraid this might be dangerous, and therefore called up his helping spirits and asked them about it. Through his helping spirits my father learned that despite the manner in which I was born, with the aid of a magic bird, and the way my life had been saved by powerful spirits, there was yet something in my soul of that which had brought about the death of all my brothers and sisters. For this reason the dead were often about me, and I could not distinguish between the spirits of the dead and real live people. Thus it was that I had gone out to play with the souls of my dead brothers and sisters, but it was a dangerous thing to do, for in the end the dead ones might keep me among themselves. My father's helping spirits would therefore now endeavour to protect me more effectively than hitherto, and my father was not to be afraid of my dying now. And after that, whenever I wanted to go out and play with the spirit children, which I always took for real ones, a sort of rocky wall rose up out of the ground, so that I could not get near them.

"The next thing I remember is hearing people talk of evil spirits, which were said to be about us; evil spirits that would bring misfortune and spoil the hunting. When I heard this I was very much afraid, for I was now old enough to understand that our life was set about with many perils, and I fell to crying. Then I remember we all went away, to escape from that dangerous place, and travelled long and far until we came to Qiqertaq (Ship Harbour Island, near Haviland Bay). It was here that I first saw the white men, and I learned later on that they were whalers. I remember some curious things from those days. There was an old woman who wanted to sell a puppy to the white men, but they would not buy it, and I thought how hard it was on the old woman, for she was very poor. I remember she tried to work magic and do the white men harm because they would not help her.

"Another thing I remember about the white men is that they were very eager to get hold of women. A man with a handsome wife could get anything he wanted out of them: they never troubled much about what a thing cost as long as they could borrow the wife now and again. And they gave the women valuable gifts. I was only a little girl myself at that time, and had but little knowledge of what took place between man and woman when they were together, but I remember there were some of our men who would have no dealings with the white men, because they did not wish to share their wives with them. But most of the men did not mind; for it is quite a common thing among us to change wives. A man does not love his wife any the less because she lies with someone else now and again. And it is the same with the woman. They like to know about it, that is all: there must be no secrets in such matters. And when a man lends his wife to another, he himself always lies with the other man's wife. But with white men it was different; none of them had their wives with them to lend in exchange. So they gave presents instead, and thus it was that many men of our tribe looked on it as only another kind of exchange, like changing wives. And there were so many things in our way of life that did not agree with the white men's ways, and they did not feel obliged themselves to keep our rules about what was taboo, so we could not be so particular in other matters. Only the white men had less modesty than our own when wishing to lie with a woman. Our men always desired to be alone with the woman, and if there was no other way, they would build a snow hut. But the white men on the big ship lived many together in one place, lying on shelves along the steep sides of the ship, like birds in the face of a cliff. And I remember a thing that caused great amusement to many, though the ones to whom it happened were not pleased. One evening when a number of women had gone to the white men's ship to spend the night there, we in our house had settled down early to rest. But suddenly we were awakened by the sound of someone weeping outside. And this was what had happened. A woman named Atanarjuat had suddenly fallen through the shelf where she was lying with one of the men on the ship, and rolled stark naked on the floor. She burst out crying for shame, put on her clothes in a great hurry and went home weeping, saying that she would never again lie with a white man. It was she whom we had heard outside our house, and as I said before, these things took place at a time when I did not rightly know what went on between man and woman. But all the same, when I heard about this, a thing most of the others laughed at, I could not help feeling that the white men must have less sense of decency than we had.

"Then I forgot all that happened at that place, and did not remember again until we came to Malukshitaq (Lyon Inlet), where we had taken land. One thing I remember from that time is that my mother always had a urine bucket for a pillow when she lay down to sleep. This she did in order that my father might be successful in his hunting. Thus she helped the hunters, and they killed a walrus. There was a great feast, and I was there, and I remember there was a fight between father and son. I was afraid, and ran away.

"All this that I have told you I remember only as in a mist. My first clear remembrance is of the time when we lived at Utkuhigjalik (Wager Bay); my father died there. Soon after his death, my mother married Mánâpik ("the very much present") but they could not live together, and it was not long before they separated, and my mother was married to a man named Higjik ("the marmot"). Shortly after, we went away from there, and lived at Oqshoriaq (the word means quartzite; it is the Eskimo name for Marble Island). There were many people there at that time, and life was very amusing. The men often had boxing matches, and there were great song feasts at which all were assembled. It was there I saw for the first time an old woman from Qaernermiut (Baker Lake). I was told that this old woman was the first who ever saw Oqshoriaq. Before that time, it was nothing but a heap of pressure ridges in the ice. It was not until later that the ice turned to the white stone we call Oqshoriaq. I remember the first time we came to that island, we had to crawl up on to the land, and were not allowed to stand upright until we reached the top. That was done then, and it is done to this day, for the Island is a sacred place: magic words made it, and if we do not show respect for it by crawling it will change to ice again, and all the people on it will fall through and drown."

— At this point in Takornâq's story the meat in the pot began to boil, and she interrupted her narration to serve up a meal. Tea was made from our own supply, and the old woman was so pleased at this little trivial courtesy, that she at once improvised a song, the words of which were as follows:

The lands around my dwelling

Are more beautiful

From the day

When it is given me to see

Faces I have never seen before.

All is more beautiful,

All is more beautiful,

And life is thankfulness.

These guests of mine

Make my house grand.

Ajaja — aja — jaja.

We then settled down to eat, but Takornâq herself would not join us, for in order to preserve the life of the delicate infant she had bought, she was obliged to refrain from eating any food cooked in a pot with meat intended for others; she must have her own special cooking pot, and eat from no other.

As soon as we had finished, she went to a store chamber at one side of the hut, and dragged out the carcase of a caribou, which she gave us with the following words:

"Go out and give this to your dogs. I am only doing as my husband would have done had he been at home."

We then went out and fed our dogs, and when we re-entered the hut, the talk naturally turned upon her husband, Padloq (properly, "he who lies face downwards"). She had already told us that she had been married several times before. She now resumed her story where she had left off, as follows:

"When I was old enough to begin taking part in games with the young men, I was married. My first husband was called Angutiashuk ("one who is not a real man"). We were only married a very short time. I did not care for him, he was no good, and so we separated. He died of hunger shortly after.

"It was not long before I was married again, this time to one named Quivâpik, but everyone was afraid of him, because he was always threatening to kill people if he did not get exactly what he wanted. He went up inland hunting caribou, and I went with him to help carry the meat. We lived quite alone, far from any people, and I often wept with misery at our loneliness. I felt the need of being among others, and having someone to talk to, for Quivâpik was a man who hardly ever spoke. We stayed up inland all that summer. The only means we had of getting fire was by using firestone (pyrites) but once we could not find any, and could make no fire. Then Quivâpik called up his helping spirits, and while doing this he cried to me suddenly:

"'Close your eyes and clutch at the air!' And I did so, and a piece of fire-stone came flying through the air and I caught it, and we were able to make a fire once more.

"Summer came to an end, and autumn set in, and when the darkness came, we could sometimes see beings in human form, but we did not know what they were. We were afraid of them, and returned home to our own place, where at that time there was scarcity of game and great want of food. Before long a walrus was captured, and then there was meat for all once more.

"Real knives of iron and steel, such as we use now, were very rare in those days, and the men often lost them. Then my husband would hold a spirit calling, and in that way recover the lost knives.

"Once while we were at Southampton Island, Quivâpik was attacked by some of his enemies, and wounded by a harpoon in one eye and one thigh, but so great a shaman was he that he did not die.

"Quivâpik once tried to catch a dead man who was trying to return to his village. A corpse thus trying to come to life again is called an an aɳᴇrlᴀrtukxiᴀq. They are persons at whose birth magic words have been uttered, so that if they die, they can come to life again and return to their place among men. But it was a hard matter for Quivâpik to catch this one, so he got another shaman to help him, and even then they did not succeed. Quivâpik said it would have been easy to bring the dead man to life again if only the moon had given leave. But the dead man's mother had sewn garments of new caribou skin on the island of Oqshoriaq, and that is not allowed there, so the moon would not let her son come to life again.

"Another time we were out after salmon, and I could not catch any. But my husband came and took the fish hook and line from me and held the hook between his legs, and after holding it there a while, he swallowed it, and drew it out from his navel, and the line the same way. After that I caught plenty of salmon.

"I was married to him for seven years, but then he was killed by some people who were afraid of him. A man named Ikumaq ('the flame') stabbed him with a snow knife, and took me to wife himself. He was not my husband for long, and when I married again, it was Padloq. It is not our custom to call our husbands by their names. I call Padloq o·maga ("the one that keeps me alive"). From the day I married him, my life became restful.

"In the course of my life, from childhood to old age. I have seen many lands, and lived in many different ways. There were times of abundance, and times of dearth and want. The worst thing I remember was when I found a woman who had eaten her husband and her childern to save herself from starvation.

"Ûmaga and I were travelling from Iglulik to Tununeq when he dreamed one night that a friend of his had been eaten by his nearest kin. Ûmaga has the gift of second sight, and always knows when anything remarkable is going to happen. Next day we started off, and there was something remarkable about our journey from the start. Again and again the sledge stuck fast, but when we came to look, there was nothing to show what had stopped it. This went on all day, and in the evening we halted at Aunerit ('the melted place', in the interior of Cockburn Land). Next morning a ptarmigan flew over our tent. I threw a walrus tusk at it, but missed. Then I threw an axe, and again missed. And it seemed as if this also was to show that other strange things were to happen that day. We started off, and the snow was so deep that we had fo help pull the sledge ourselves. Then we heard a noise. We could not make out what it was; sometimes it sounded like a dying animal in pain, and then again like human voices in the distance. As we came nearer, we could hear human words, but could not at first make out the meaning, for the voice seemed to come from a great way off. Words that did not sound like real words, and a voice that was powerless and cracked. We listened, and kept on listening, trying to make out one word from another, and at last we understood what it was that was being said. The voice broke down between the words, but what it was trying to say was this:

"'I am not one who can live any longer among my fellows: for I have eaten my nearest of kin'.

"Now we knew that there should properly be no one else in this part of the country but ourselves, but all the same we could distinctly hear that this was a woman speaking, and we looked at each other, and it was as if we hardly dared speak out loud, and we whispered:

"'An eater of men! What is this we have come upon here!'

"We looked about us, and at last caught sight of a little shelter, built of snow with a piece of a skin rug. It lay half hidden in a drift, and was hardly to be noticed in the snow all round, which was why we had not made it out before. And now that we could see where it was the voice came from, it sounded more distinctly, but still went on in the same broken fashion. We went slowly up to the spot, and when we looked in, there lay a human skull with the flesh gnawed from the bones. Yes, we came to that shelter, and looking in, we saw a human being squatting down inside, a poor woman, her face turned piteously towards us. Her eyes were all bloodshot, from weeping, so greatly had she suffered.

"'Kivkaq,' she said (literally, 'you my gnawed bone,' which was her pet name for Padloq, whom she knew well) 'Kivkaq, I have eaten my elder brother and my children.' 'My elder brother' was her pet name for her husband. Padloq and I looked at each other, and could not understand that she was still alive and breathing. There was nothing of her but bones and dry skin, there seemed indeed hardly to be a drop of blood in all her body, and she had not even much clothing left, having eaten a great deal of that, both the sleeves and all the lower part of her outer furs. Padloq bent down quite close, to hear better, and Ataguvtâluk — for we knew her now, and could see who it was — said once more:

"'Kivkaq, I have eaten your fellow-singer from the feasting, him with whom you used to sing when we were gathered in the great house at a feast.'

"My husband was so moved at the sight of this living skeleton, which had once been a young woman, that it was long before he knew what to answer. At last he said:

"'You had the will to live, therefore you live.'

"We now put up our tent close by, and cut away a piece of the fore curtain to make a little tent for her. She could not come into the tent with us, for she was unclean, having touched dead bodies. When we went to move her, she tried to get up, but fell back in the snow. Then we tried to feed her with a little meat, but after she had swallowed a couple of mouthfuls, she fell to trembling all over, and could eat no more. Then we gave her a little hot soup, and when she was a little quieter, we looked round the shelter and found the skull of her husband and those of her children; but the brains were gone. We found the gnawed bones, too. The only part she had not been able to eat was the entrails. We gave up our journey then, and decided to drive back with her to Iglulik as soon as she felt a little stronger. And when she was once more able to speak, she told us how it had all come about. They had gone up country hunting caribou, but had not been able to find any; they then tried fishing in the lakes but there were no fish. Her husband wandered all about in search of food, but always without success, and they grew weaker and weaker. Then they decided to turn back towards Iglulik, but were overtaken by heavy snowfalls. The snow kept on, it grew deeper and deeper, and they themselves were growing weaker and weaker every day; they lay in their snow hut and could get nothing to eat. Then, after the snow had fallen steadily for some time there came fierce blizzards, and at last her husband was so exhausted that he could not stand. They kept themselves alive for some time by eating the dogs, but these also were wasted away and there was little strength in them as food: it simply kept them alive, so that they could not even die. At last the husband and all the children were frozen to death; having no food, they could not endure the cold. Alaguvtâluk had been the strongest of them all, though she had no more to eat than the others; as long as the children were alive, they had most. She had tried at first to start off by herself and get through to Iglulik, for she knew the way, but the snow came up to her waist, and she had no strength, she could not go on. She was too weak even to build a snow hut for herself, and the end of it was she turned back in her tracks and lay down beside her dead husband and the dead children; here at least there was shelter from the wind in the snow hut and there were still a few skins she could use for covering. She ate these skins to begin with. But at last there was no more left, and she was only waiting for the death to come and release her. She seemed to grow more and more dull and careless of what happened: but one morning, waking up to sunshine and a fine clear sky, she realised that the worst of the winter was over now, and it could not be long till the spring. Her snow hut was right on the road to Tununeq, the very road that all would take when going from Iglulik to trade there. The sun was so warm that for the first time she felt thawed a little, but the snow all about her was as deep and impassable as ever. Then suddenly it seemed as if the warm spring air about her had given her a great desire to go on living, and thus it was that she fell to eating of the dead bodies that lay beside her. It was painful, it was much worse than dying, and at first she threw up all she ate, but she kept on, once she had begun. It could not hurt the dead, she knew, for their souls were long since in the land of the dead. Thus she thought, and thus it came about that she became an inukto'majoq, an eater of human kind.

"All this she told us, weeping; and Padloq and I realising that after all these sufferings she deserved to live and drove her in to Iglulik, where she had a brother living. Here she soon recovered her strength, but it was long before she could bear to be among her fellows. It is many years now since all this happened, and she is married now, to one of the most skilful walrus hunters at Iglulik, named Iktukshârjua, who had one wife already; she is his favourite wife and has had several more children.

"That is the most dreadful thing in all my life, and whenever I tell the story, I feel I can tell no more."

— With these words she set about arranging a sleeping place for Nasaitsordluarssuk and myself on the bench, and for a long time did not speak. Quietly she prepared a little meal for herself, after having entertained us so lavishly, and always taking great care that none of her food came in contact with any we had left: for that might have been dangerous to the adopted child that she was vainly endeavouring to keep alive. She then crawled up on to the bench behind her lamp and soon fell asleep.

Takornâq was the first of all the Hudson Bay Eskimos whose confidence I gained. In her narrative that first evening we were together she gave me, as it were, in a single sum, the life I had now to investigate in detail. Early next morning we set off again, but not before extracting a promise from Takornâq to come and stay with us for a while as soon as her husband returned.

She kept her word. Padloq proved to be just the right sort of husband for her. He was a quiet and persevering hunter, and a good traveller, and we afterwards arranged for them to assist us in the work of the expedition; they took up their quarters on Danish Island and stayed with us throughout one winter. My intercourse with them was of great importance to my work, for Padloq was a shaman, and from him and Takornâq together I obtained much valuable information.

Padloq and I often made excursions together, and on one of our many journeys an event occurred which showed him in such a characteristic light that I include the story here. It happened during a walrus hunt on the edge of the ice, out in Frozen Strait.

Padloq might fairly be said to be of a humble, religious turn of mind, and it was his firm belief that all the little happenings of everyday life, good or bad, were the outcome of activity on the part of mysterious powers. Human beings were powerless in the grasp of a mighty fate, and only by the most ingenious system of taboo, with propitiatory rites and sacrifices, could the balance of life be maintained. Owing to the ignorance or imprudence of men and women, life was full of contrary happenings, and the intervention of the angákut was therefore a necessity. Padloq himself was always most concerned about the adopted child, Qahîtsoq, on which he and Takornâq alike lavished all their affection. The poor, emaciated creature, a boy, seemed hardly capable of life, and despite all the efforts of Takornâq to feed him and fatten him, with constant meals of seal-meat soup and blubber from her own mouth, he was always whining, even in sleep. Padloq himself once said of the poor little weakling — which after all lacked nothing but its own mother's milk — that "he was as a guest among the living". By way of linking him more strongly to life, they had him betrothed to a fine healthy little girl, who was, like himself, less than a year old. But all efforts were unavailing, the boy died ere the winter was out. During his lifetime, however, the little fellow had furnished material for many conversations, and in the course of these talks with Padloq I could not but think, many a time, how unjust it is to accuse primitive peoples of being only concerned with their food and how to get it with least trouble. True, they say themselves that a man's only business is to procure food and clothing, and while fulfilling his duties in this respect he finds, in his hunting and adventures, the most wonderful experiences of his life. Nevertheless, men may be to the highest degree interested in spiritual things; and I am thinking here not only of their songs and poems, their festivals when strangers come to their place, but also of the manner in which they regard religious questions, wherein they evince great adaptability and versatility. This it is which always gives their accounts that delightful originality which is the peculiar property of those whose theories are based on experience of life itself. Their naturalness makes of them philosophers and poets unawares, and their simple and primitive orthodoxy gives to their presentment of a subject the childlike charm which makes even the mystic element seem credible.

One evening, Padloq, who was an enthusiastic angákoq, had been particularly occupied in studying the fate of the child. We were lying on the bench, enjoying our evening rest, but Padloq stood upright, with closed eyes, over by the window of the hut. He stood like that for hours, chanting a magic song with many incomprehensible words. But the constant repetition, and the timid earnestness of his utterance, made the song as it were an expression of the frailty of human life and man's helplessness in face of its mystery. Then suddenly, after hours of this searching in the depths of the spirit, he seemed to have found what he sought; for he clapped his hands together and blew upon them, washing them, as it were, in fresh human breath, and cried out:

"Here it is! Here it is!"

We gave the customary response:

"Thanks, thanks! You have it."

Padloq now came over to us and explained that Qahîtsoq had been out in a boat the previous summer, the sail of which had belonged to a man now dead. A breeze from the land of the dead had touched the child, and now came the sickness. Yes, this was the cause of the sickness: Qahîtsoq had touched something which had been in contact with death, and the child was yearning now away from its living kind to the land of the dead.

We settled down then all together on the bench, waiting for the meal that was cooking. It was midwinter, the days were short, and the evenings long. A blubber lamp was used for the cooking, the pot being hung over it by a thong from a harpoon stuck into the wall. Suddenly the pot gave a jump, and rocked to and fro, as if someone had knocked it. The heat had melted the snow at the spot where the harpoon was fixed, the harpoon had slipped down a little, jerking the thong, and making the lumps of meat hop in their soup. Padloq, still under the influence of his trance, leapt up from his place and declared that we must at once shift camp, and move up on to the firm old winter ice; for our hut here was built among some pressure ridges forming a fringe between the old ice and the open sea. We had taken up this position in order better to observe the movements of the walrus, but Padloq now asserted that we were too near the open sea, and were filling the feeding grounds of the walrus with our own undesirable emanations. They did not like the smell of us. And the sea spirit Takánakapsâluk was annoyed, and had just shown her resentment by making our meat come alive in the pot. This is said to be a sign often given to people out near the fringe of the ice, and we were obliged to accept it. But the rest of us were not at all inclined to turn out just at that moment, all in the dark, and shift camp. It would be several hours before we got into new quarters, and hours again before we got anything to eat. Therefore, despite Padloq's protest, we stayed where we were, and when we had eaten our fill, crept into our sleeping bags. None of us dreamed how nearly Padloq had been right until next morning, when to our horror we found a crack right across the floor. It was only a narrow one, but wide enough for the salt water to come gurgling up through it now and again. The roof of the hut was all awry over by the entrance, and on knocking out a block of snow, we saw the black waters of the open sea right in front of us. The young ice on which the snow hut was built had broken away, but instead of being carried out to sea, it had drifted in at the last moment among some high pressure ridges kept in place by a small island.

After that I was obliged to promise Padloq that I would in future have more respect for his predictions as a shaman, should we again be out hunting on the ice-edge; for, as Padloq put it, the spirits can, at times, speak through some poor ignorant fellow otherwise of no account, and that to such purpose that even those far wiser may be well advised to heed what is said.

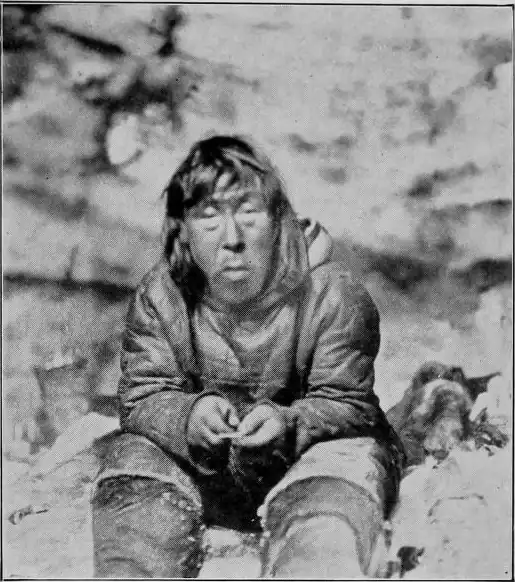

One bitterly cold day in March, during our first winter, a sledge suddenly appeared from behind some drifts at the back of the house, and pulled up a moment later at the door. The driver was an old shaman named Inernerunashuaq, whom I had met previously, at Takornâq's village; he had come down to us now with his whole family, in the hope of living for some indefinite period in abundance on our supplies of meat. He was beyond all comparison the most unskilful hunter of his tribe, and all that winter he had only managed to kill one caribou. He had thus no meat for food, and no skins to clothe his wife and children. The entire band were also in such a pitiably ragged state that it was a marvel they could travel at all in the cold wind. As it was they looked almost perishing. Almost all the natives we had encountered up to now had been more or less well off, or at least adequately clad, and in these regions that is the main thing, or nearly so. It was painful to us all, therefore, to see this naked poverty in the midst of winter. I had already heard, up at one of the villages, where everybody knows all about everybody else, that Inernerunashuaq had lived for the past month, with his wife, his children and his dogs, on the meat of a single bearded seal given him by the ever generous Padloq.

While sympathising heartily with their plight, however, I was obliged to welcome them with some reserve. We had already learned by experience that undue hospitality might bring down upon us visitors of the poor relation type whom we could not afford to keep, but found it almost impossible to get rid of. In several cases we had been forced to ask them, in so many words, to leave, as we were obliged to husband our stores for the many journeys to be made. And the family which now appeared on the scene was; I knew, one of the worst of its kind.

As soon as the miserable equipage had halted, and the wretched dogs sought shelter close to the house, Inernerunashuaq came running up to me, uttering a jumble of incoherent sounds that no one could be expected to understand. I fancied for a moment he must have lost his senses. And my companions were equally mystified, when Tûglik came up and explained that one of her husband's principal helping spirits was the spirit of a white man, and that this had now, on our arrival at the white men's dwelling, entered into him, and was talking white man's talk in our honour. The old shaman himself played his part with force and conviction, and when 1, entering into the game, addressed him in Danish, he showed not the slightest confusion, but answered again in his own made-up gibberish, as if he understood every word I said. All this made a certain impression on some Eskimos of Inernerunashuaq's own tribe who were present; they actually believed that their shaman was speaking a language which I understood. I was anxious to make the man's acquaintance, and was therefore obliged to back him up. Accordingly, I refrained from any exposure of his trickery, but when I felt he had exerted himself sufficiently, broke in upon his inspired nonsense and informed him that we were unfortunately on the point of setting out on a journey ourselves, and would not be able to entertain visitors for any length of time; they could, however, stay a few days if they liked, provided he would undertake to answer various questions I wished to ask him. The poor fellow, doubtless accustomed to be received with far less consideration elsewhere, was sufficiently delighted at this. I told him that I knew he was a great shaman, and wished to learn something of his art. This further increased his satisfaction, and he went off very cheerfully to set about building a snow hut close to our house. As soon as this was done, and the family with their few miserable belongings had moved in, I invited the whole party to a feed of frozen caribou meat and boiled walrus. It was really a delight to give these hungry people food, though they devoured it with a greediness that seemed almost inhuman. It looked as if their stomachs could never be filled; and I called to mind an old Greenland proverb which runs: "A dog is always ready to eat; for it never eats so much but that it can begin again: only a hungry human being eats beyond reason."

Next day we started work. I got Inernerunashuaq into the little apartment I used as a study, and questioned him as to all he might know regarding the traditions of his people. Unfortunately, I soon found that his brain was too confused for me to take his statements as generally valid. Nor was he altogether reliable in himself; if he found any difficulty about the question, he was not afraid to invent an answer on the spur of the moment, and though his explanation of the matter might be interesting enough, it was not what I wanted.

I take this opportunity of drawing attention to a point of importance in connection with this work. I have often been asked how I manage to check the accuracy of statements made in the course of such conversations. Many people are in opinion that artful shamans would very often try to deceive me with false information. This might perhaps happen, but I would point out that if one has but the right sort of relations with the Eskimos, and understanding of their ways, with a thorough knowledge beforehand of their religious ideas and how their imagination expresses itself therein, it will never be difficult to distinguish between information derived from their ancient traditions and the unscrupulous invention or embroiderings of irresponsible individuals. I have never questioned a native on serious matters, things of life and death, unless I knew him well enough to judge as to the value of what he might tell me. Inernerunashuaq was not a liar or a humbug, but a man of weak intellectual capacity, and in the course of our talks, he felt he was called upon to maintain his dignity as a shaman; he was, indeed, really afraid that a confession of ignorance might offend the spirits on whom his whole art depended. It was therefore he so often tried to make do with nonsensical meanderings, to such an extent that his wife, who, though not an angákoq, was an intelligent woman with plenty of sound common sense, had to intervene with an explanation of her own. And though Tûglik herself could not but be aware that her husband was by no means brilliant, she had nevertheless the greatest respect for his magic powers.

Inernerunashuaq, or, as he requested us to call him, Unaleq, the Cree Indian, had immigrated from the west some twenty years before, from the neighbourhood of Pelly Bay, where the nearest of the Netsilik Eskimos are established. I was anxious to learn something as to the views of these people, but after we had spent a whole day trying to solve the mystery of how the first human beings appeared on earth, it was as usual Tûglik who related the following, which she had heard from her great-grandmother:

"There was once a world before this one, and in that world lived human beings who did not belong to our tribe. The earth at that time rested on pillars, but one day the pillars gave way, and all things disappeared into nothing, and the world was emptiness. Then there grew up out of the earth two men; they were born and were grown up all at once, and they wished to beget children. By means of a magic song, one of them was changed into a woman, and they had children. These were our earliest forefathers, and from their offspring all the lands were peopled."

— — —

There was no denying the fact that Unaleq was a foolish and ridiculous old fellow, but since he nevertheless enjoyed a considerable reputation as a shaman, I was interested in him as a phenomenon. For the Eskimos hold that spirits will often show a deliberate preference for one otherwise incapable, and express themselves through such a medium. Unaleq was not brilliant, and he was a wretched hunter, who, unless helped out by others, let his family starve and go about in rags. All the same an atmosphere of mystery surrounded him. People who were really in trouble often applied to him, possibly considering that a man who knew so little about the everyday things of life might perhaps for that very reason have special knowledge of matters hidden and mysterious to his fellows.

Unaleq had ten helping spirits, and when I asked him for their names, he was greatly upset at such a want of respect. I pressed him nevertheless to tell me; but he insisted then on our shutting ourselves up in my little study, when he drew pictures of these helping spirits for me, and whispered their names in my ear. They were for the most part deceased Eskimos and Indians that he had met on solitary hunting expeditions up in the hills, he could not say how it had come about. The mightiest and most influential of them all was Nanoq Tulorialik ("The Bear with the fangs"). This was a giant in the shape of a bear, who came as often as he called. There were also the following deceased members of the Netsilik tribe; Angusingarna and Alu, both men, Arnagnagluk and Kavliliúkâq, both women. Then there were two nameless Indians of the Chipewyan tribe, two mysterious mountain spirits of those which are called Norjutilik, the name being derived from a peculiar tuft at the end of a stiff thong extending up above their heads from the point of the hood. Finally, there was a woman of the Tuneq tribe, or the people that inhabited the country before the present Eskimos made their way to the coasts: this woman's name was Kamingmalik.

Otherwise, he could tell me nothing more definite about these spirits. He merely said that their power lay in their own unfathomable mysteriousness. They had appeared to him in the first instance without his asking, he had touched them, and they had thereby become his property or his servants once and for all, coming to help him whenever he called. We agreed that Unaleq should give a demonstration of his art the same evening. I was just then making preparations for a sledge journey down to the Inland Eskimos west of Chesterfield, and the purpose of his seance, or to·nrinᴇq, as he himself called it, was to ensure a free passage for our party, with plenty of game and no misfortunes on the road. He would ask the advice of the Giant Bear, Tulorialik; when that particuliar spirit deigned to occupy his body, he, Unaleq, could transform himself into a bear or a walrus at will, and was able to render great service to his fellow men by virlue of the powers thus acquired. In payment for the seance, he was to have one of the biggest and handsomest of our snow knives; for a shaman would insult his helping spirits if he were to invoke them without adequate remuneration from the persons on whose behalf they were asked to intervene. And Unaleq had never possessed such a snow knife as we had.

In the evening, after dark, he came in, followed by his whole family, ready to fulfil his promise. The spirits, however, were not called upon until after he, assisted by his wife and children, had devoured a mass of walrus meat sufficient, in his judgement, to act as ballast in his inner man. Not until then did he declare himself ready to begin. There were several Eskimo visitors present, and all were eager to see what the evening would bring forth. We had hoped that Unaleq could have his trance in the mess room, where all could be present and witness his transformation to Tulorialik, but the old man declared very firmly that the apartment in question, being used by all, was too unclean for his spirits to visit. The invocation must take place in my little study, for he took it for granted that I, when I shut myself up there alone, would be occupied with lofty thoughts, like himself. He then required all the lamps to be put out, and crawled in under my writing table. His wife carefully hung skins all round the table, so that her husband was now hidden from all profane glances. All was in darkness, we could only wait for what was to come. For a long time not a sound was heard, but the waiting only increased our anticipations. At last we heard a scraping of heavy claws and a deep growling. "Here it comes" whispered Tûglik, and all held their breath. But nothing happened, except the same scraping and growling, mingled with deep, frightened groans; then came a fierce growl, followed by a wild shriek, and at the same moment, Tûglik dashed forward to the table and began talking to the spirits. She spoke in their own particular spirit language, which I did not understand at the time, but will give later on. The spirits spoke now in deep chest notes, now in a high treble. We could hear, in between the words, sounds like those of trickling water, the rushing of wind, a stormy sea, the snuffling of walrus, the growling of bear. These however, were not produced with any superlative art, for we could distinguish all through the peculiar lisp of the old shaman acting ventriloquist. This sitting lasted about an hour, and when all was quiet once more, Tûglik informed us that her husband, in the shape of the fabulous bear, had been out exploring the route we were to follow on our long journey. All obstacles had been swept aside, accident, sickness and death were rendered powerless, and we should all return in safety to our house the following summer. All this had been communicated in the special language of the spirits, which Tûglik translated for us, and at last, when this was done, Unaleq crawled out from under the table, exhausted by the heat.

Despite the extreme naïveté of the whole proceeding, this spirit seance was to me of great interest. For it was one of the first at which I was present, and I could not but feel astounded at the manner in which it impressed the Eskimos themselves. They were altogether fascinated, as if they really felt a breath of some supernatural power in the pitiful acting which any critical observer could see through at once. I saw here how great was the faith of these people in their wizardry, and how even the most mediocre practitioner can gain adherents, because all are ready to believe without question. And, as I was to learn in a moment, the old shaman himself believed in his helping spirit. He was a poor ventriloquist, but no humbug all the same; and this was proved in rather curious wise.

There was a little shed outside where we kept our trade goods, and when the general excitement after the seance had subsided, Unaleq and I went out to get the snow knife I had promised him. It was wonderful weather, perfectly calm and still, for once, without a cloud in the sky, and bright moonlight. The soft light had something of that unreality which always lies in the yellowish gleam of the moon over white, dazzling snow, the very light that spirits of the air would choose to come forth in, according to the Eskimo account. The charm of the winter evening seemed also to have made an impression on Unaleq, and the dogs, when they saw us come out, threw back their heads and uttered a monotonous howl that produced a strange, uncanny effect in the quiet of the night. The Eskimos always believe there are spirits about when the dogs howl in unison.

We stood still for a moment, affected by the beauty that surrounded us. Then suddenly Unaleq asked a question.

"Can you also call up spirits?"

"Just as well as you can" I answered quite sincerely.

"What would happen if you did" he enquired eagerly.

Half thoughtlessly, half on purpose, I answered:

"The roof of my house would fly up to heaven and with it whichever of us two is the poorer shaman."

To my great astonishment, Unaleq leapt aside so suddenly that he fell down into a deep hollow in the snow just behind us, and lay there jerking his limbs about, half senseless, until I helped him up. I laughed, and tried to explain that my answer was only meant in fun, and that I had not the slightest pretensions to any power over spirits. But his own conviction was so strong, his will to believe so thoroughly sincere, that nothing could now efface his first strong impression. Whatever I might say now, Unaleq fully and firmly believed that I was a great shaman. So impressed was he indeed, that when we reentered the house shortly after, he could not refrain from telling the others at once all that had passed. And the funny thing about it was that while all the others thoroughly understood my joke, the shamian himself alone maintained that I must be a great shaman all the same, and that his own power over the helping spirits had really been in serious peril.

I willingly admit that it was not very considerate of me thus to play upon the old man's simplicity; on the other hand, it was my business to study his mind in its natural state, and that was my excuse. And it certainly led me to understand that these Eskimos really believe one shaman can steal another's helping spirits; for all through that winter, whenever Unaleq was unsuccessful in his operations with the spirits, he declared to his fellows that it was my fault; his helping spirits were with me. This was due partly to the fact he had described them to me by his drawings, and had mentioned their names. I was loth to hurt the simple old man to no purpose, and therefore, in the following year. I went to his village and there declared solemnly that I had come to give him back all his helping spirits; I had forbidden them to follow in my footsteps, and they were now his once more, wholly and entirely. This was the second lie I told Unaleq, but I lied this time with a good conscience, for it made him happy, and freed him from the fear which had plagued him, that I should have taken away his power.

Tûglik, who, unaffected by all minor failings, was a blind admirer of her husband's art, now proposed that we should finish up the evening by playing children's games. She was anxious that I should forget all about her husband's passing weakness as soon as possible, and like a wise woman, chose an old dance song. She had long since discovered that when I touched on the question of Unaleq's relations with the spirils, it was always more self-interest than faith. But she knew that I was very fond of songs and stories, which they themselves did not rank so high as gifts of the spirits. So she drew forth a couple of little girls, little bundles of skins with ruddy cheeks, and placed them one opposite the other. Then, as soon as she started the song, which was sung at a breathless rate which left her gasping, the little girls joined in, crouching down and hopping with bent knees in time to the music:

Aja· — ja· — japape!