Illustrations of Japan/Part 2

Japan.

Part Second.

Decription of the Ceremonies Customary in Japan at Marriages

and Funerals: Particulars Concerning the Dosia

Powder, &c.

Introduction

to the

Description of the Marriage Ceremonies

of

the Japanese.

In compliance with the urgent request of the Society of Sciences established at Batavia, I made very particular inquiries concerning the marriages of the Japanese. As it would be impossible to form any correct idea of them from the mere account that a foreigner might draw up, I have preferred giving a translation of a work on the subject printed in the country itself, and adding the necessary explanations between parentheses. This work, which enters into the most minute details, may lead the reader to suppose that the Japanese sink the more important matters in an ocean of frivolities; but before he adopts so harsh a notion respecting a people who are not inferior in politeness to the most distinguished nations of Europe, he ought to consider their present situation, and to acquire a smattering at least of their history.

On the first arrival of the Dutch in 1609, the Japanese were allowed to visit foreign countries. Their ships, though built on the plan of the Chinese junks, boldly defied the fury of tempests. Their merchants were scattered over the principal countries of India; they were not deficient either in expert mariners or adventurous traders. In a country where the lower classes cannot gain a subsistence but by assiduous labour, thousands of Japanese were disposed to seek their fortune abroad, not so much by the prospect of gain, as by the certainty of being enabled to gratify their curiosity with the sight of numberless objects that were wholly unknown to them.

This state of things formed bold and experienced sailors, and at the same time soldiers, not surpassed in bravery by those of the most warlike nations of India.

The Japanese, accustomed from their infancy to hear the accounts of the heroic achievements of their ancestors, to receive at that early age their first instruction in those books which record their exploits, and to imbibe, as it were, with their mother’s milk the intoxicating love of glory, made the art of war their favourite study. Such an education has, in all ages, trained up heroes; it excited in the Japanese that pride which is noticed by all the writers who have treated of them, as the distinguishing characteristic of the whole nation.

Having a keen sense of the slightest insult, which cannot be washed away but with blood, they are the more disposed to treat one another in their mutual intercourse with the highest respect. Among them suicide, when they have incurred disgrace or humiliation, is a general practice, which spares them the ignominy of being punished by others, and confers on the son a right to succeed to his father’s post. As with us, the graceful performance of certain bodily exercises, is considered an accomplishment essential to a liberal education, so among them, it is indispensably necessary for all those who, by their birth or rank, aspire to dignities, to understand the art of ripping themselves up like gentlemen. To attain a due proficiency in this operation, which requires a practice of many years, is a principal point in the education of youth. In a country where sometimes a whole family is involved in the misconduct of one of its members, and where the life of every individual frequently depends on the error of a moment, it is absolutely requisite to have the apparatus for suicide constantly at hand, for the purpose of escaping disgrace which they dread much more than death itself. The details of the permanent troubles recorded in their annals, and the accounts of the first conquests of the Dutch in India, furnish the most complete proofs of the courage of the Japanese. The law, which has since forbidden all emigration, and closes their country against strangers, may have taken away the food which nourished their intrepidity, but has not extinguished it: any critical event would be sufficient to kindle their martial sentiments, which danger would but serve to inflame, and the citizen would soon be transformed into a hero.

The extirpation of the Catholic religion, and the expulsion of the Spaniards and Portuguese, caused dreadful commotions in Japan for a number of years. The sanguinary war which we (the Dutch) carried on with those two nations, who were too zealous for the propagation of Christianity, and the difference of our religion, procured us the liberty of trading there, to the exclusion of all the other nations of Europe. The Japanese, perceiving that incessant seditions were to be apprehended from the secret intrigues of the Roman Catholics, and the numerous converts made by them, found at length that in order to strike at the root of the evil, they ought to apply to the Dutch, whose flag was then the terror of the Indian seas.

The bold arrest of governor Nuyts, at Fayoan, in 1630, showed them that the point of honour might every moment involve them in quarrels for the purpose of revenging the insults which their subjects might suffer in foreign countries or at sea. The decree of the Djogoun, which confiscated the arms of the people of Sankan, wounded the vanity of the Japanese. Numbers of malefactors, to avoid the punishment due to their crimes, turned pirates, and chiefly infested the coast of China, the government of which made frequent complaints on the subject to that of Japan. The nine Japanese vessels, then trading with licenses from the Djogoun, were to be furnished with Dutch passports and flags, in case of their falling in either with Chinese corsairs, or with our ships cruising against those of the Spaniards of Manilla and the Portuguese at Macao. The residence of Japanese in foreign countries rendered their government apprehensive that it would never be able entirely to extirpate popery. These various considerations induced the Djogoun, in the twelfth year of the nengo quanje (1631), to decree the penalty of death against every Japanese who should quit the country: at the same time the most efficacious measures were taken in regard to the construction of vessels. The dimensions were so regulated, that it became impossible to quit the coast without inevitable danger.

Cut off from all other nations, encompassed by a sea liable to hurricanes, not less tremendous for their suddenness than their violence, and thereby secured from the continuance of hostile fleets in these parts, the Japanese gradually turned their whole attention to their domestic affairs. Their respect for the Dutch by degrees diminished. A mortal blow was given to our importance in this country by the removal of our establishment from Firando to Nangasaki in 1640, the chief objects of which were, 1. To afford some relief to the inhabitants of that imperial city, who, since the expulsion of the Spaniards and Portuguese, were daily becoming more and more impoverished; 2. To keep us more dependent, by placing us under the superintendence of their governors. For the sake of our commerce, we patiently submitted to the destruction of our recently erected store-houses, the heavy expense incurred by the removal, and our imprisonment in the island of Desima, where the Portuguese had their buildings, and which we had heretofore in derision denominated their dungeon. The humiliating treatment to which they then first subjected us, according to our records of those times, caused the Japanese to remark that they might act towards us in a still more arbitrary manner.

Having no idea of the governments of Europe, ignorant that the mightiest empires there owe their greatness and the stability of their power to the benign influence of commerce alone, the Japanese hold the mercantile profession in contempt, and consider the farmer and the artisan as more useful members of society than the merchant. The little respect that still continued to be paid us was at length wholly withdrawn, on the reduction of the island of Formosa by Coxinga. A native of Firando, and carrying on an extensive commerce at Nangasaki, Coxinga solicited assistance from the court of Yedo against the Chinese. Miko-no-komon-sama, great-grandfather of the prince of Firando in my time, supported him with all his influence. The Djogoun rejected his application, because he would not embroil himself with that empire. Coxinga, attacking the Chinese in the island of Formosa, at the same time turned his arms against us. Though he was not openly favoured, yet our archives attest that the Japanese policy encouraged his hostilities, since the government took no notice of our complaints, regarding us no doubt, as too dangerous neighbours, and not conceiving itself secure so long as the empire should be exposed to the attacks of an enterprising people. The vexations to which we have since been exposed have frequently induced the Company to think of dissolving the establishment. Some of the Japanese, well-disposed towards the Dutch, even advised us to threaten them with it, and to recover our credit by the reduction of Formosa. The former was tried with some success, but we were not strong enough to attempt the latter.

Since the suppression of the rebellion at Arima and Simabarra, in 1638, the peace of the empire has not been disturbed: it was not interrupted either by the attempt of Juino Djosits and Marbasi Fiuia, in 1651, or by that of Jamagata Dayni, in 1767, the particulars of which I have given in the Secret Memoirs of the Djogouns. At the very commencement of the present dynasty, the government made regulations, as salutary as the welfare of the state, the happiness of the people, and the maintenance of order in the interior of the empire required. The active spirit of the Japanese could not fail to seek new objects, and by degrees their attention was turned to the establishment on fixed bases of all the observances due to each individual, according to his station in the different circumstances of life: so that every one might have precise rules for the government of his conduct towards others of every class, from the highest to the lowest. These very particular regulations were printed; otherwise a long life would scarcely suffice for acquiring a thorough knowledge of etiquette.

The military profession, as we have observed, is regarded by the Japanese as the most noble pursuit: a predilection for it is therefore encouraged in boys from their earliest years, by a suitable education, and by the Festival of Flags, which is held on the fifth of the fifth month. As they grow older, they apply themselves to the history of their country, and to the study of the duties attached to different offices, in which the sons regularly succeed their fathers. The study of the Chinese language also, in which they seldom make any very great proficiency, though persons above the lowest class devote their attention to it at all ages, affords them incessant employment. As their best works are written in that language, it is a disgrace for persons of distinction to be unacquainted with it. The precepts of Confoutsé have been in all ages explained and commented on in the public schools. From the remotest antiquity, the Japanese have respected the Chinese as their masters, and paid homage to their superior attainments. To them they went for many centuries to complete their education, and to augment their stores of knowledge. Since the prohibition of foreign travel, the only resource left them is to study the works of the Chinese, which they purchase with great avidity, especially since the zeal of the missionaries, by making them acquainted with the process of printing, has opened a new career to their fondness for study.

Several of our interpreters were well versed in the history of China and Japan. Among those who most excelled in this respect were Josio-Kosak, Nanioura-Motoisera, Naribajasi Zïubi, Naribasi Zenbi, Nisi-Kitsrofe, Foli-Monsuro, and likewise Matsmoura-Jasnosio, who, at my departure, was appointed tutor to the prince of Satsuma. I mention their names out of gratitude for the kind assistance which they afforded me in my researches. During my residence in Japan, several persons of quality at Yedo, Mijako, and Osaka, applied themselves assiduously to the acquisition of our language, and the reading of our books. The prince of Satsuma, father-in-law of the present Djogoun, used our alphabet to express in his letters what he wished a third person not to understand. The surprising progress made by the prince of Tamba; Katsragawa Hoznu, physician to the Djogoun; Nakawa-Siunnan, physician to the prince of Wakassa, and several others, enabled them to express themselves more clearly than many Portuguese, born and bred among us at Batavia. Considering the short time of our residence at Yedo, such a proficiency cannot but excite astonishment and admiration. The privilege of corresponding with the Japanese above-mentioned, and of sending them back their answers corrected, without the letters being opened by the government, allowed through the special favour of the worthy governor, Tango-no-Kami-Sama, facilitated to them the means of learning Dutch.

In the fifth chapter of the first volume of the work of Father Charlevoix, a mixture of good and bad, and swarming with errors, the character of the Japanese, as compared with that of the Chinese, is very justly delineated. Their vanity incessantly impels them to surpass one another in bodily exercises, as well as in the accomplishments of the mind. The more proficiency they make, the stronger is their desire to see with their own eyes all the curious things, the description of which strikes their imagination. When they turn their eyes to neighbouring nations, they observe that the admission of foreigners is not injurious to the government; and that a similar admission of strangers into their own country would furnish them with the means of studying a variety of arts and sciences of which they have but vague notions. It was this that induced Matsdaira-Tsou-no-Kami, the extraordinary counsellor of state, to propose in 1769 the building of ships and junks calculated to afford the Japanese facilities of visiting other countries, and at the same time to attract foreigners to Japan. This plan was not carried into execution in consequence of the death of that counsellor.

Though many Japanese of the highest distinction and intimately acquainted with matters of government, still consider Japan as the first empire in the world, and care but little for what passes out of it, yet such persons are denominated by the most enlightened Inooetzi-no-Kajerou, or frogs in a well, a metaphorical expression, which signifies that when they look up, they can see no more of the sky than what the small circumference of the well allows them to perceive. The eyes of the better informed had been long fixed on Tonoma-yamassiro-no-kami, son of the ordinary counsellor of state Tonomo-no-kami, uncle to the Djogoun, a young man of uncommon merit, and of an enterprising mind. They flattered themselves that when he should succeed his father, he would as they expressed it, widen the road. After his appointment to be extraordinary counsellor of state, he and his father incurred the hatred of the grandees of the court by introducing various innovations, censured by the latter as detrimental to the welfare of the empire. He was assassinated on the 13th of May 1784, by Sanno-Sinsayemon, as related in my Annals of Japan. This crime put an end to all hopes of seeing Japan opened to foreigners, and its inhabitants visiting other countries. Nothing more, however, would be required for the success of such a project, than one man of truly enlightened mind and of imposing character. At present, after mature reflection on all that is past, they are convinced that the secret artifices and intrigues of the priests of Siaka were the real cause of the troubles which for many years disturbed the peace of the empire.

In 1782 no ships arrived from Batavia, on account of the war with England. This circumstance excited general consternation not only at Nangasaki, but also at Osaka and Miyako, and afforded me occasion to stipulate with the government for a considerable augmentation in the price of our commodities for a term of fifteen years. Tango-no-kami, the governor, with whom I kept up a secret intercourse, proposed to me in 1783 to bring over carpenters from Batavia to instruct the Japanese in the building of ships and smaller vessels, a great number of barks employed in the carriage of copper from Osaka to Nangasaki having been wrecked on their passage, which proved an immense loss to the government. Knowing that it would be impossible to comply with his request, because none of the common workmen employed in our dock-yards in the island of Java possessed sufficient skill, and the masters were too few to allow any of them to be spared for ever so short a time; I proposed to Tango-no-kami to send with me, on my departure from Japan, one hundred of the most intelligent of his countrymen to be distributed in our yards, assuring him that pains should be taken to teach them all that was necessary to qualify them for carrying his views into execution at their return. The prohibition which forbids any native to quit the country, proved an insurmountable obstacle. On the arrival of a ship in the month of August, I caused the boats to manœuvre from time to time in the bay with Japanese sailors on board, which much pleased the governor, but did not fulfil his intentions. I then promised that when I reached Batavia, I would have the model of a vessel built, and present him with it on my return, together with the requisite dimensions, and all possible explanations: this I accordingly did in August the following year. The death of Yamassiro-no-kami, of which I received information immediately after my arrival at Batavia, annihilated all our fine schemes. Having finally quitted the country for Europe in the month of November in the same year, I know not whether my instructions on this point have been followed or not.

A plan so important as that here mentioned, other schemes which I pass over in silence, and the ordinary duties of my post, occupied my whole time. When therefore, I sat down to describe the manners and customs of the Japanese so imperfectly known in Europe, I had not leisure to draw up an accurate account of all the ceremonies attending the marriages of persons of quality; but was obliged to confine myself to the description of those common among farmers, artisans, and tradesmen. By comparing them with what is the practice in Europe and elsewhere among persons of those different classes the reader will be enabled to judge to what a length the Japanese carry the observance of the forms of politeness and etiquette.

The Editor has extracted from Charlevoix the following description of the mode of constructing and arranging private houses in Japan, as it will enable the reader to understand with the greater facility the account of the marriage ceremonies observed in that country.

The houses of private individuals must not exceed six fathoms in height, and few buildings are so lofty unless they be intended for store-houses. The palaces of the emperors themselves have but one floor, though some private houses have two; but the ground-floor is so low, that it can scarcely be used for any other purpose than stowing away the articles necessary for common use. The frequency of earthquakes in Japan has occasioned this mode of building: but, if these houses are not to be compared with ours for solidity or height, they are not inferior to them either in cleanliness or convenience. They are, with few exceptions, of wood. The ground-floor is raised four or five feet as a precaution against damp, for the use of cellars seems to be unknown in this country: and, as these houses are very liable to be consumed by fire, there is in each of them a spot enclosed with walls of masonry, in which the family deposits its most valuable effects: the other walls are made of planks, and covered with thick rugs, which are very nicely joined together.

The houses of persons of quality are divided into two series of apartments. On one side is that of the women, who, in general, never show themselves; and on the other, is what we should call the drawing-room, where visitors are received. Among the trades-people and inferior classes, the women enjoy more liberty, and are less careful to conceal themselves from view: but, upon the whole, the sex is treated with great respect, and distinguished by extraordinary reserve. Even in the most trifling matters the utmost politeness is shown to women. The finest pieces of porcelain, and those cabinets and boxes which are so highly esteemed and carried all over the world, instead of serving to decorate the apartments in ordinary use, are kept in those secure places above-mentioned, into which none but particular friends are admitted. The rest of the house is adorned with common porcelain, pots full of tea, paintings, manuscripts, and curious books, arms, and armorial bearings. The floor is covered with thick double rugs, bordered with fringe, embroidery, and such-like ornaments. According to the law or the custom of the country, they must all be six feet in length, and three in breadth.

The two suites of apartments into which the body of the house is divided consist of several rooms, separated by mere partitions, or rather by a kind of skreens, which may be moved forward or backward at pleasure; so that an apartment may be made larger or smaller as there may be occasion[1]. The doors of the rooms and the partitions are covered with paper, even in the most splendid houses: but this paper is adorned with gold or silver flowers, and sometimes with paintings, with which the cieling is always embellished. In short, there is not a corner of the house but has a cheerful and pleasing appearance. This mode of arrangement renders houses more healthy: in the first place, because they are entirely built of fir and cedar; in the second, because the windows are so contrived, that by changing the place of the partitions, the air is allowed a free passage through them. The roof, which is covered with boards or shingles, is supported by thick rafters; and, when a house has two floors, the upper is usually built more solidly than the lower. It has been found by experience, that a house so constructed, resists the shocks of earthquakes better. In the architecture of the exterior there is nothing very elegant. The walls, which, as I have observed, are of boards, and which are very thin, are covered in many places with a greasy earth found near Osaka; or instead of this earth, they give the outside a coat of varnish, which they lay on the roofs also. This varnish is relieved with gilding and paintings. The windows are filled with pots of flowers, which, according to Caron, they have for all seasons; but when they have no natural flowers they make shift with artificial ones. All this produces an effect that pleases the eye, if it does not gratify it so highly as beautiful architecture would do.

Varnish is not spared in the interior. The doors, the door-posts, and a gallery which usually runs along the back of the house, and from which there is a descent into the garden, are covered with it, unless the wood be so beautiful as to make them wish not to conceal the veins and shades; in this case they merely lay on a thin coat of transparent varnish. In the apartments are to be seen neither chairs nor benches; for it is customary, in Japan, as in all the rest of Asia, to sit on the ground. To avoid soiling the mats or rugs which cover the floor and serve for seats, they never walk on them in shoes, or more properly speaking, sandals, which are put off on entering the house. They sleep also upon these rugs over which people in good circumstances spread a rich carpet, and a wooden machine serves to support it. This is a kind of box, nearly cubical, composed of six small boards very neatly joined together and varnished; it is about a span long, and not quite so broad. Most of the household utensils are of thin wood covered with a thick varnish of a deep red. The windows are of paper, and have wooden shutters within and without; they are never closed but at night, and are not seen in the day-time, their sole use being to prevent persons from entering the house by favour of the darkness, either through the court or the gallery.

In the apartment for the reception of company, there is always a large cabinet opposite to the door, and against this cabinet visitors are placed. Beside the cabinet is a buffet, on which are put religious books; and, in general, by the door there is a kind of balcony, so contrived that without rising, you may have a view either of the country, the street, or the garden. As the use of fire-places is unknown in Japan, there is in the largest apartments a square walled hole, which is filled with lighted charcoal, that diffuses heat sufficient to warm the whole room. Sometimes a low table covered with a large carpet is set over the fire, and people sit upon it when the cold is very severe, nearly in the same manner as they do in Persia, on what is called a kartsü. In apartments in which a fire-place cannot be made, they supply the want of it by copper and earthen pots, which produce nearly the same effect. Instead of poker and tongs they use bars of iron to stir the fire, which they do with as much address as they use small varnished sticks instead of forks to eat with.

In the houses of very wealthy persons and in great inns are to be seen very curious articles, which serve to amuse travellers, such as: 1. A large paper, on which is represented some deity, or the figure of some person eminent for virtue, with an appropriate and frequently very rich border, in the manner of a frame. 2. Grotesque Chinese figures, birds, trees, landscapes, always in a masterly style, covering skreens. 3. Pots of flowers. 4. Perfuming-pans of brass or copper, in the shape of cranes, lions, or other animals. 5. Pieces of furniture of rare wood. 6. Toilets of carved work. 7. Plate, porcelain, &c.

- ↑ It may be seen from the engravings which accompany the description of marriages, that they have also sliding partitions; that a partition is composed of three or four shutters or leaves, running one before another on parallel grooves; and that, by this mode of separation, they can in a few moments make one large room out of several small ones.

Description

of the

Ceremonies Observed in Japan

at the

Marriages of Farmers, Artisans, and Tradesmen.

The marriage ceremonies of the highest and those of the lowest classes are totally different. Very curious particulars relative to this subject are given in several Japanese works, particularly in the Jomé-tori-tiofo-ki, in which the manner of conducting the bride out of the house of her parents is accurately described. The same thing is also to be found in the Kesi-foukoro, of which I here give a translation, together with the plates belonging to it, containing all that is to be observed at the marriages of farmers, artisans, and tradesmen;

The presents that are to be sent to the residence of the bride when the match is agreed on;

The ceremonies observed from the commencement till the conclusion of the marriage;

The apparel and what is most commonly worn on such occasions;

The furniture, ordinary and extraordinary;

The manner of contracting the engagement at three times, with a single earthenware jug full of zakki, and when three such jugs are employed;

How the nearest relatives on each side meet, and bind the new alliance by drinking zakki;

The manner of adorning the tekaké, the fikiwatasi, and the sousous; and the order in which the company are placed.

All this is shown in the Kesi-foukoro by several engravings on wood, the description of which is divided into numbered chapters, that whatever relates as well to marriage as to the value of the presents, among the highest, middling, and lowest classes, may be thoroughly understood by all. Thus

| No. | 1. | contains the list of the presents and the manner in which they are arranged; |

| 2. | The manner in which they are previously arranged at the house of the father; | |

| 3. | What is to be observed in regard to the paper; | |

| 4. | What ought to be written upon it; | |

| 5. | The form and manner of paying consgatulations, and the order in which the presents are arranged at the residence of the bride; | |

| 6. | The manner of delivering the lists of presents, &c. |

These numbers amount to 192. The substance of them is as follows:—

§ 1. Gives a description of the presents, and of what is to be observed in regard to their value, with reference to the condition and circumstances of each person. These presents consist of

| 150 | pieces of money, of the value of 4 taels 3 marcs each. |

| 5 | rolls of white pelongs. |

| 5 | rolls of red gilams. |

| 10 | single rolls, or 5 double pieces of red stuff for lining. |

| 15 | packets of silk wadding. |

| 5 | bunches of nosi, or dried rock-leech. |

| 3 | handfuls of dry sea-cats. |

| 50 | pieces of sea-lentil. |

| 53 | kommelmaas, or two or three couple of wild ducks. |

| 1 | tray with two bream. |

| 2 | kegs of zakki. |

Each person is at liberty to give the eleven articles composing such a present, or only nine, seven, or three, just as he pleases; representations of them, as well as of the trays on which they are offered, will be found in plates 4, 6, 9, and 10.

§ 2. The father of the bridegroom, after setting out the present at his house, invites all his relations, male and female, and likewise the mediators, and regales them with zakki and other refreshments.

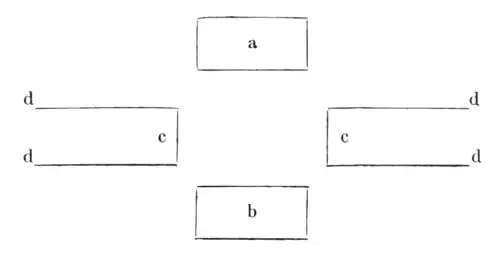

§ 3. To make out a list of the presents they use fosio paper, or sougi-fara paper, according as it is longer or shorter. This paper is folded length-wise in the middle; and only one side is written upon. When the present is large, and one side is not spacious enough to hold the description of them, they take take-naga paper. This list must be written with thick ink, otherwise it would not be accepted.

§ 4. This list is made out as follows:

a Mokrok, or List of Presents.

| b | above, | pieces of money, | below | 150 | pieces. |

| c | above |

white pelongs, | below |

5 | rolls. |

| d | above |

red gilams, | below |

5 | rolls. |

| e | above |

red stuff, | below |

5 | double pieces. |

| g | above |

bunches of nosi, | below |

5 | |

| h | above |

sea-cat, | below |

3 | handfuls. |

| i | above |

sea lentil, | below |

50 | pieces. |

| k | above |

kommelmaas, | below |

50 | pieces. |

| l | above |

bream, | below |

2 | |

| m | above |

zakki, | below |

2 | kegs. |

| At the side | n. | Izjo, or the end. |

| o. | Niwa-Kanjemon, name of the bridegroom’s father. | |

| p. | the date. | |

| q. | Ima-i-Sioyemon, name of the bride’s father. |

§ 5. The presents having been carried to the house of the bride’s father, the messenger arranges them in the order in which they are enumerated in the list. If the place be rather too small for displaying them, still they must not be set out indistinctly; each of the articles must lie separately, but they may be laid as closely as possible to one another.

§ 6. Among the middling class trays with legs are used, and among the lower trays without legs.

§ 7. The messenger sent to the residence of the bride must be accompanied by the mediator. The former pays this compliment:—

“Niwa-Kanjemon is exceedingly flattered that Ima-i-Sioyemon-Sama gives his daughter to his son. For this reason he sends him this present, as a token that he wishes him durable health.”

§ 8. At the house of the bride’s father, a servant in decent attire, as well as the messenger, must be on the watch to receive the present. After comparing it with the list, he politely accepts it, and informs the master of the house of the present and the message.

§ 9. The messenger and mediator are then conducted into any suitable apartment.

§ 10. The conductor, his people, and the messengers, are then led into another apartment, by persons appointed for that purpose; who, after they are there seated, leave them for a moment. Meanwhile a cup of tea, and the apparatus for smoking, are handed round to each of the persons thus seated.

§ 11. If the messenger is a person of respectability, he is regaled with soni soup, famagouris (a species of muscle) with their sauce; a koemisiu, (a box of sweatmeats), and several other kinds of refreshments, the whole served up in small bowls exquisitely varnished, with covers. If he is an ordinary person, he is treated only with soni soup and soeimono, (fish chopped very small), with sauce in bowls of a more common kind, but also with covers. To these are added a box of balls made of fish and zakki.

§ 12. It frequently happens that the messenger and the master of the house are of different rank; if the former be of higher rank, the other comes to him and compliments him; in the contrary case, he is not expected to do so.

§ 13. The receipt contains a list of the presents at full length, and concludes with these words:—

“The present described above has been duly received by Ima-i-Sioyemon, who also wishes durable health to Niwa-Kanjemon.”

§ 14. The receipt being considered as an important document, the name of the father is inserted in it, and that of the messenger is not mentioned.

§ 15. At the expiration of three days, the messenger and those who accompanied him to the residence of the bride, receive a counter-present proportionate to what they brought; for instance,

The messenger 2 pieces of money, 1 roll of stuff for a cloak of ceremony, 10 quires of sougi-fara paper.

The conductor, 2 itsibs of gold, which make a half-koban, and 5 quires of sougi-fara paper.

Each servant 3 strings of sepikkes, and one quire of fansi paper.

§ 16. The day after that on which the present is carried to the house of the bride, the mediators are complimented by the parents of the young couple.

§ 17. The mediators are charged to ascertain, on behalf of the bride, the arms of the bridegroom, and the length of his robes.

§ 18. The two parties must settle between them on what day the marriage is to take place.

§. 19. The following articles are prepared for the bride at her own home:

- Long robes, wadded with silk for winter;

- A wedding dress, white, embroidered with gold or silver;

- Another dress, with a red ground;

- Another with a black ground;

- Another of plain white stuff;

- Another of plain yellow;

(People of quality have for this purpose costly stuffs, the ground of which, called aja, is sprinkled with squares of the same stuff, crossed each way, thus, 田, named saji-waifies. Such is the costume indispensably necessary on all great festivals. For mourning they have also stuffs with this aja ground, but without squares).

A number of summer robes, both lined and single, and all the other requisites of a wardrobe, as girdles, bathing gowns, chemises, under robes, fine and coarse, a bed-gown with sleeves, (a thick furred robe), a rug to sleep on, bed-clothes, pillows, gloves, carpets, bed-curtains, head-dresses, (usually of silk gauze, which young females wear when they go abroad), a light girdle (which is covered by the broad one, and serves to tuck up the robes with long trains), plain strings, (to tie round the cotton gown worn in bed), a silk cap, a furred cap of cotton, long and short towels, a cloak, a covering for the norimon, silk buskins, and a bag with a mixture of bran, wheat, and dried herbs, to be used in washing the face.

§ 20. The santok, or pocket-book, must contain a small bag of toothpicks, some skeins of moto-iwi (thin twine made of paper to tie the hair), a small looking-glass, a little box of medicines, and a small packet of the best kalambak.

§ 21. Several kinds of paper are also provided, as sikisi, tansac, nobé-kami, sougi-fara, fansi, fosio, mino-kami, tage-naka, and maki-kami, or paper in rolls for writing letters.

§ 22. Various trifling articles are also put up, as:

A kollo (a kind of harp,) a samsi (a sort of guitar), a small chest for holding paper, an inkhorn, a pincushion, several sorts of needles, Daïri dolls, a box of combs, a mirror with its stand, a mixture of iron and black to blacken the teeth, (the distinguishing mark of married women, some blackening them the moment they are married, and others when they first become pregnant), curling-tongs for the hair, scissors, a letter-case, a case of razors, several small boxes varnished or made of pasteboard or osier, dusters, a small bench for supporting the elbows when the owner has nothing to do, a case of articles for dressing the hair, small dolls, an iron for ironing linen, a large osier basket (to hold the carpets and various articles of linen used by women), a tub with handles, a small and very smooth board, a small sabre, called mamouri-gatana, with a white sheath in a little bag (this sabre, when carried about them, is thought to drive away evil spirits, and to preserve them from all infectious exhalations; and the same effects are ascribed to the sabres of the men), complimentary cords (small cords made of paper, painted with different colours, and gilt or silvered at each end, used to tie round presents), nosi or dried rock leech (a small piece of which is attached to every present in token of congratulation), silk thread, a small tub to hold flax, several slender bamboos, furnished with brass or copper points for spreading or drying silk stuffs upon after they are washed, kino-fari (a kind of pins for stretching silk stuffs upon mats), thread, tobacco cut small, large dolls, circular fans, common fans, terrines with their dishes; the whole resembling the articles daily used by the bride.

§ 23. Several books are added, such as the following:—

- The Fiak-nin-ietsu, or the hundred poems, composed by different authors.

- The Ize Monogatari, by Ize, a female attendant of one of the wives of the Daïri, showing how a certain Narri Fira had lived in adultery with Nisio-no-Ki-saki, one of the wives of the Daïri, which, to his indelible disgrace, was published in a great number of books.

- The Tsouri-tsouri-gousa, a collection of tales, from which moral precepts are drawn, in eight volumes.

- The Gensi Monogatari, or, History of Gensi-no-Kimi, a kinsman of one of the Dairïs, containing an account of his adventures in several countries, and likewise some poems by Mourasaki-Zikieb, in fifty volumes.

Or,

- The Koget-su another version of the Gensi-Monogatari, written in the language of the learned, by Kigin.

- The Hizu-itze-day-zu, in twenty-one volumes, with poems composed under forty-three Daïris, from the 5th year of the Nengo Ingi (905), in the eighth year of the reign of the sixtieth Daïri, Daygo-ten-o, to the tenth year of the Nengo-Jeykjo (1438), the tenth year of the reign of the one hundred and third Daïri, Go Fannazono-no-in.

Or,

- The Ziu-san-day-zu, thirteen volumes, containing all the poems composed under the thirteen Daïris, from the second year of the Nengo-Fywa (1223), to the tenth year of the Nengo-Jeykyo, (1438).

- The Manjo-zu, a collection of ancient poems from the reign of Saisin-ten-o, the tenth Daïri, to Daygo-ten-o, the sixtieth.

- The Sagoromo, or, explanation of the Gensi Monogatari, in sixteen volumes.

- The Jeigwa Monogatari, history of a spendthrift, from which may be drawn useful moral precepts of economy.

- Ona-si-zio, that is, four books for the use of females, viz.:

- The Daygakf, or moral precepts of Confoutsé.

- The Rongo, his lessons to his disciples.

- The Mozi, a defence of his works, by Mozi.

- The Tynjo, or treatise on the advantage of observing a due mean in all things, by Zizi, grandson of Confoutsé. These works, published in the learned language, Gago, with the kata-kana, or women’s letters, have been re-printed expressly for them.

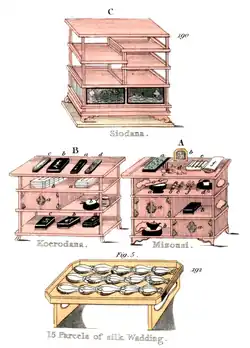

- The Kai-awasi-o-goura-waka-sougo-rok, or, description of a certain toy for women, consisting of two high boxes, filled with shells of famagouris, gilt in the inside, and painted with figures of men, animals, flowers, plants, &c. In this book there is, by the side of each shell, a short poem relative to the subject which it exhibits. See the representation of these boxes marked with the letters CC, plate 3.

- The Sei-Sionagon-tji-je-ita, the duties of a female in the married state, by Sei-sionagon, waiting-woman to one of the wives of a Daïri.

And, lastly, - The Konrei-kesi-fonkouro. Konrei, properly signifies marriage; kesi, the seed of the poppy; foekoero, a sack. These three words joined together, intimate that the most minute circumstances relating to the marriages of farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers, compared with those which are to be observed at marriages of persons of quality, are described in this work with the greatest accuracy.

§ 24. At the residence of the bride many things are also provided for the entertainment of the relations, as tea-cups, tea-tables, boxes for eatables, zakki pitchers and waiters, boxes of sweetmeats, boxes to lean upon, plates for confectionary, a sake-zin (containing two zakki), pitchers, and several dishes and plates which fit exactly one in another; such a sake-zin, enclosed in a larger box is taken along on any party of pleasure, to prevent embarrassment), a pot, a tobacco-bon (apparatus for smoking), a sougo-rokban (a kind of chess-board), small tongs, a little bar to hang towels on, several instruments for burning kalambak, a small box containing all the requisites for smoking (this is used on ordinary occasions, the other only on festivals), pipes, a desk to lay books upon while reading, a low table with four legs.

§ 25. Some coarse articles are also provided, such as a lantern, a small tub for washing hands, a small bowl of varnished wood with lid and handle, for pouring out water, a hat, a parasol, a norimon, with a covering of oiled paper against rain, two kinds of slippers, wooden sandals mounted on pattens, and a box for the slippers.

§ 26. Several other articles are prepared, such as a mizousi, or dressing table (see plate 9, letter A), a Koero-dana (see the same plate, letter B, where a description is given of these two pieces of furniture), two boxes with painted shells (already mentioned in section 23, and represented in plate 3, CC), a screen, boxes for victuals, a tans, or ordinary drawer, a square osier basket, a large chest, an oar to hang clothes upon, a chest for pressing sashes, two fasami-fako (small portmanteaus), a box for pastry, and several other trifling things.

§ 27. The day after the wedding, the bride receives a present from each person who comes to see her in her apartment; she takes care to provide beforehand various articles to give in return. If she had not sufficient, she would be obliged to apply to her husband, which would be a disgrace to her and her women, being yet but a stranger in the house.

To prevent such a mortification, they prepare the undermentioned packets of gold, silver and copper coin. The present which the bride makes must always be in proportion to that she receives.

|

2 maas. | ||

|

3 ― | ||

|

3 kondorins. | ||

|

5 kondorins. | ||

|

or a fourth of a koban. | ||

|

3 taels | ||

|

4 taels 5 maas. | ||

|

7 taels 5 maas. |

A quantity of packets, each containing two small strings of zeni or sepikkes.

A quantity of other packets of one string each.

There should be a considerable quantity of the two latter sorts.

On each packet is stuck a small piece of nosi; and the different packets are kept in separate boxes.

Care is also taken to have in readiness fifty quires of sougi-fara and fansi paper, of which ten, five, or three, quires are attached to each counter-present, in proportion to its value. (This provision of paper seems very small when compared with the packets; but, as each visitor adds a few quires to his present, these are used for the counter-presents). On these quires of paper a small piece of nosi is stuck, as upon the packets; and they are likewise tied with complimentary strings. (See plates 6 and 10, fig. 1, 2, 3, and 4.)

At the entrance of the bride’s apartment is seated a woman, who, to prevent mistakes, keeps an account in a memorandum-book of all the presents and counter-presents.

§ 28. Some nagamouts, or trunks, and tans, or drawers, are then prepared, and each of them is put into a linen bag: care is taken to have the bags in readiness before the day is fixed for the nuptials. These bags are generally of a dark blue or green colour, painted with the arms of the bride, and tied with some strips of nosi, or with creeping plants.

§ 29. The widest cloth is best for these bags; it is usually eight or ten inches broad; twenty-two feet eight inches long for the tans, and forty-one feet for the nagamouts, kousira-siak measure. (The Japanese have two kinds of measures of length, the kousira and the kani-siak. The first is used for all kinds of stuff that are woven; the other by surveyors and carpenters; fifty-two inches of the former are equivalent to sixty-five of the latter measure.)

It would be superfluous to describe how the breadths are to be sewed together.

§ 30. Each of the articles mentioned in the 19th and following sections, being provided at the house of the bride, an invitation is sent to the mediator and his wife, who, in token of congratulation, are treated with zakki and soeimono (several kinds of soup in terrines with covers).

§ 31. A day, marked in the almanac as a fortuate one, is fixed for removing the whole to the house of the bridegroom. The catalogue is written on a sheet of paper folded lengthwise, and the upper part only is written upon. This catalogue is delivered on a waiter. The following list, written over the whole page is delivered, on the contrary, without waiter.

§ 32. The plate which I have marked with the letter B, in the Japanese original, represents the manner of writing.

- a. The list of what is necessary for house-keeping. Each article is then named separately.

- b. Isio, or the end.

Here the fathers are not named.

§ 33. That is only done in the receipt which is simply worded:

a. Receipt of, &c.

Each article received is then mentioned,

- b. Isio, or the end.

- c. What is mentioned above has been received, and specially delivered by us.

- d. The date.

- e. The servant of Niwa Kanjemon.

- e. The servant of Niwa Sitsijemon.

- f. The servant of Ima-i-Sioyemon, Koufe-dono.

- g. The seal of Sitsijemon.

§ 34. The mediator first proceeds to the house of the bridegroom, to receive what is to be sent thither. A number of servants are in waiting; some to attend to the door, and to open it on the arrival of the articles; and others to lead the bearers aside, that they may not obstruct the entrance, and to prevent confusion.

The messenger, the superintendent, and the mediator, are conducted into a separate apartment, where they are served with refreshments. The persons of less consequence are conducted into another room, where some one remains with them and supplies them with refreshments

A cup of tea is first handed to each of them, and then tobacco; the messenger, superintendent, and mediator, are supplied with soni and soeimono soups, famagouris, in their sauce, a box of dainties, sea-spider, fish-balls, and other dishes prepared beforehand, as well as zakki.

If the mediator is of inferior rank to the messenger and the superintendent, he remains with them the whole time; if not he quits them.

A waiter is brought them with three jugs of zakki, one of which is always larger than the others.

As he soni soup, hastily prepared for the domestics, might not be properly cooked, nor sufficiently good in quality, another soup is given to them; or instead of soup, three or five cakes, in proportion to their size, are set before each, wrapped in sougi-fara, or fansi paper, tied with complimentary strings; on each packet are two dry gonames (a species of pilchard).

These packets are given to them as well as the soeimono soup (a preparation of famagouris), and zakki; but this is not done if they have the soni soup, for which reason they prefer the packets.

§ 36. The bearers are rewarded according to the value of the articles: each of them receives three small strings of sepikkes or more, according to the circumstances of the bridegroom’s father.

§ 37. The betrothing and nuptials take place on the same day. No priest is ever required for the marriage ceremonies.

On the day fixed, one of the female servants of the second class, who is known to be the most intelligent, is sent to the house of the bride to receive her. (There are three classes of women servants: the first make the apparel of the mistress, dress her hair, and keep her apartments in order; the second wait on her at meals, accompany her when she goes abroad, and attend to other domestic duties; and the third are employed in cooking and various menial offices.)

§ 38. At the bride’s house, she is treated with refreshments; a female meanwhile bearing her company.

§ 39. The bride’s father invites all his kinsfolk, and gives them an entertainment before his daughter is conducted to the habitation of the bridegroom.

§ 40. Some servants of the second class there await the arrival of the bride.

§ 41. The sakki is poured out by two young girls, one of whom is called the male butterfly, and the other the female butterfly. (These appellations are derived from their sousous, or zakki jugs, each of which is adorned with a paper butterfly, to denote that, as those insects always fly about in pairs, so the husband and wife ought to be continually together. For a representation of these jugs, see plate 4, letter A, No. 179.)

Before the male butterfly begins to pour out, the other pours a little zakki out of her jug into that of her companion.

The manner of pouring out the zakki is governed by particular rules, which will be noticed hereafter.

§ 42. The Tekaké, the Fikiwatasi, and the Sousous, ought to be ready, and also a woman to hand them round. They are described in § 177, 178, and 179, and the manner in which they are to be decorated, and the ceremonies to be observed in presenting them, will be mentioned in the sequel.

§ 43. The Simaday and the Osiday ought likewise to be in readiness (See Plate 11, A and B.)

§ 44. The boxes of dainties are also set in order. There are three sorts:—

- One with dried sea-cat, doubled, then rolled and cut small;

- One with the roe of dried fish;

- One with kobo (or bullock’s tail), a species of black carrot.

People of quality have other boxes which require more ceremony.

§ 45. At the house of the bridegroom are provided numerous articles necessary for the wedding, viz.:—

Tea-cups, tea-tables, apparatus for smoking, bowls and platters for the entertainment, porcelain dishes, large and small plates, salvers, small cups, basins for the soeimono soup, two kinds of candlesticks, long and short; lamps, large and small lanterns, (the former are lighted up in the house, the others are to carry about in the hand); candles, chaffing-dishes, zakki pitchers, small sticks used in eating; different sorts of jugs for zakki, some for single portions, others for three, five, or nine; all kinds of beautiful furniture for the toko, and for decorating the apartment; the requisites for making tea, and many other articles of too little importance to be enumerated.

§ 46. A list of the dishes is made out, with directions how they are to be prepared.

§ 47. The norimons, or palanquins, are arranged at the house of the bride in the following order:

- 1. The norimon of the mediator’s wife;

- 2. That of the bride, in which are her mamori and her mamon-gatana (See § 22);

- 3. That of the bride’s mother;

- 4. That of her father.

The mediator precedes them to the house of the bridegroom.

(Every Japanese carries with him his mamori; some put it in the santok, or portfolio; others suspend it from the neck by a small cord, like the children and travellers. It is properly a small square or oblong bag, containing a drawing or image of some deity, as Kompra, Akifa, Atago, Fikozan, Bouzenbo, Souwa, Tenzin, or others. These images are made either of gold or silver, or of copper, iron, wood, or stone; and are supposed to preserve from misfortune such as cherish in their hearts a sincere respect for one of these deities).

When the party has left the house in the norimons, a fire is made at the door or entrance.

(We find in the work Sinday-no-Makei, that the goddess Fensio-Daysin, or Daysingou, the symbol of the sun, and one of the Tji-sin-go-day, or five terrestrial divinities, being continually at variance with her brother, the god of the Moon, Sasan-no-Ono-Mikotto, fled to the cavern of Ama-no-t-Wato, in the province of Fiuga, and closed up the entrance with a great stone, regardless of the state of the country, which was thus left in utter darkness. Her servant, Fatjikara-O-no-Mikotto, frequently came to speak to her, but without being able to make her hear him. Chancing one day to meet with several of his companions in front of the cavern, they kindled a great fire, round which they danced to the sound of various instruments. Daysingou, wishing to know what could be the cause of this unexpected merriment, pushed away the stone a little to gratify her curiosity. This was just what Fatjikara anticipated; he immediately seized the stone in both hands, and hurled it with such force into the air, that it fell on the mountain of Foga-kousi, in the province of Sinano. In commemoration of this miracle a temple was built on the spot, and called Fogakousi-no-Miozin. Near this spot was another cavern to which she afterwards retired, blocking up the mouth with a stone; it is even asserted that she still lives there. The priests daily carry before the entrance offerings, consisting of pure alimentary substances, as raw pears, and rice well washed: but as any person who should see her would be struck blind, they hold their offerings behind them, and walking backwards, thus approach the cavern, set them down on the ground, and run off as fast as they can without looking that way. They declare that they frequently hear her chewing the pears. Intelligent persons laugh at this story, and suppose that the cavern must be the haunt of a serpent or some other animal.

By the artifice of Fatjikara light was restored to the earth. (Hence originate all the matsouris or fairs, and the custom of lighting a fire when the bride leaves the house of her parents.)

§ 48. The lantern of the bride is painted with her arms. She is dressed in white, being considered, thenceforward, as dead to her parents.

§ 49. It is customary to send a man and woman very early in the morning to the house of the bridegroom, to decorate the bride’s apartment, and set it in order.

§ 50. If all the ceremonies are to be observed, there should be on each side of the entrance to the house of the bridegroom, a mortar with some small cakes of rice pounded and boiled, for the purpose of making the woutie-aivase-motie. On the left of the entrance is stationed a man, on the right a woman, both advanced in years. The moment the bride’s norimon reaches the house, they pound these cakes ever so little, at the same time saying, the man: “A thousand!” the woman: “Ten thousand years!” (This is a compliment: the first part alluding to a crane, which is said to live a thousand years; the second to a tortoise, which is asserted to live ten thousand years.) As the norimon passes between them, the man pours his cakes into the woman’s mortar, and they begin to pound together. What is thus pounded by both at once is called woutie-aivase-motie. (This is an allusion to the cohabitation of man and woman in marriage).

§ 51. With this pounded matter are made the kagami-motie, or two cakes laid one upon another, which are placed as an ornament within the toko: their size is not fixed. What remains of the pounded cakes is mixed in the soup, called soni-motie, made of cakes. (See plate 1, b.)

This ceremony is performed or omitted according as the nuptials are celebrated with more or less pomp. Thus the kagami-motie may be made by kneading the matter into the required shape, since the cakes in the mortars are composed only of boiled rice.

§ 52. The norimon of the bride is brought within the passage, where the bridegroom stands to receive it in his dress of ceremony: he slightly touches the front pole with his hand; the bride reaches to him through the little window in front, her mamori, or small bag, containing the image of some deity. He takes it of her and gives it to one of her women, who carries it into the apartment prepared for the reception of the company, and hangs it upon a hook.

This ceremony is also performed in a different manner, as follows:—

As soon as the norimon is within the passage, there is a woman seated there, having a small lantern, and several females behind her; one of these is to receive the mamori and the mamori-gatana, before the bride quits her norimon and to deliver them to one of her women. Another then leads the bride by the hand to her apartment; the woman with the lantern goes before; she who carries the mamori and mamori-gatana follows, hands the former to the bridegroom, who sits at the entrance of the second apartment, and takes the latter directly to the apartment of the bride.

The bridegroom immediately delivers the mamori to the female servant placed at the entrance of the house to receive it: she carries it into the apartment prepared for the entertainment, and there hangs it up to a small hook.

§ 53. In this case the lantern used to serve to give the bridegroom a view of the bride. If he disliked her, the match was broken off, the matter was arranged by means of the mediators, and the next day she was sent home. Such cases formerly occurred; but at present beauty is held in much less estimation than fortune and high birth, advantages to which people would once have been ashamed to attach so much value. This custom has been by degrees entirely laid aside, on account of the mortification which it must give to the bride. At present when a young man has any intention of marrying a female, whom he deems likely, from the situation of her parents, to be a suitable match, he first seeks to obtain a sight of her: if he likes her person, a mediator, selected from among his married friends, is sent, and the business is soon arranged.

People of quality have neither lantern nor mediator, because the parents affiance their children in their infancy, and marriage always follows. Should it so happen that the husband dislikes the wife, he takes as many concubines as he pleases. This is also the practice among persons of the inferior classes. The children are adopted by the wife, who is respected in proportion to the number of her children.

Before the time at which I am writing, the bride was not allowed, in case of the bridegroom’s death previously to the consummation of the nuptials, to marry again. This custom no longer obtains either among the common people, or even among the princes and grandees of the empire; yet, if the present Djogoun, who, previously to his being elected hereditary prince in 1779, was betrothed to the daughter of the prince of Satsuma, had died before the consummation of the marriage, the princess would have been obliged to remain single all her life. Had he been sooner elected successor to the throne, he would have been obliged to marry a princess of his own family, or of the court of the Daïri. At any rate it was a stroke of policy to ally himself with the prince of Satsuma, as will be seen in the Secret Memoirs of the Djogouns of the present dynasty.

In ancient times, the following custom prevailed in the province of Ozu. Whoever took a fancy to a girl, wrote his name on a small board, called nisi-kigi, and hid it between the mats in the ante-chamber of her house. These boards showed the number of her lovers, and remained there till she took away that of the man whom she preferred. At present the choice of a wife depends, throughout the whole empire, on the will of the parents: of course there is seldom any real affection in these matches, and the husband cares but little about his wife. All the men, from the highest to the lowest, either keep concubines or frequent brothels.

§ 54. The Tekaké, the Fikiwatasi, and the Sousous, are in the apartment contiguous to that in which the wedding is to be held (See Plate 8, a. b. c.). They are removed into the latter on the arrival of the bride, and set before the toko, a kind of alcove, formed by the highest and the most distinguished place in the apartment, which is easily discovered at the first glance.

§ 55. The bride is then led by the hand, by one of her waiting-women, to her proper place in this apartment. Her attendant, called kaizoje, or assistant, sits down at her right, and another takes her place at her left.

§ 56. The bridegroom then leaves his room and comes to this apartment.

§ 57. As soon as he is seated, the female mentioned in § 42, takes the tekaké, and presents it first to the bridegroom, then to the bride, and afterwards sets it down again before the toko.

This presentation of the tekaké, is but a compliment of welcome, for neither the bridegroom nor the bride takes any thing from it, each merely making a slight inclination.

§ 58. The first cupbearer, or the male butterfly, then takes the fikiwatasi and places it before the bride (See Plate 1, e.)

§ 59. The second cupbearer, or the female butterfly, follows the first, takes the sousous, and carries them into the adjoining apartment.

§ 60. The first leaves the apartment, takes her sousou, or jug, in her right hand, touches it slightly with her left, then holds it by the bottom between both hands, and seats herself before the fikiwatasi, which is consequently between her and the bride. The other follows her, holds her sousou in the same manner, and sits down behind the first. (See Plate 1, fig. 8, 12, and 13, and letter e.)

The first, before she pours out, turns every time a little to the left; the second then pours a little zakki into her sousou. In pouring, they always hold the sousous at the bottom with both hands; they are filled with cold zakki, hot being never drunk at weddings.

§ 61. The zakki-san-gon, or san-san-koudo, denotes the manner in which the bridegroom binds himself to the bride, by drinking zakki out of earthen bowls at three times three draughts.

This is done with three or with two bowls; but the latter method is practised only by the common people, who then use only the uppermost bowl.

The mediator and his wife are present at the ceremony.

In the first case, the three bowls, called doki or kaivaraké, stand one in another on the fikiwatasi; the bride takes the uppermost, and holds it in both hands while some zakki is poured into it. She sips a little, does the same a second and a third time, and then hands the bowl to the bridegroom: he drinks three times in like manner, puts the bowl under the third, takes the second, drinks out of it three times, and hands the bowl to the bride; she drinks three times, puts the second bowl under the first, takes the third, drinks three times, then gives it to the bridegroom, who does the same, and afterwards puts this bowl under the first. The apparatus is then removed.

The common people use only two bowls: the bride takes the lowermost, holds it in both hands, while a little zakki is poured into it, which she drinks at three draughts. She then hands the bowl to the bridegroom, who does the same, and gives it back to the bride. She again drinks three times, after which the apparatus is removed.

Each time that the bride and bridegroom have drunk, they set down the bowl on the fikwatasi, the male butterfly passes her left hand through the aperture at the foot, and presents it in this manner to both parties, holding her sousou in her right hand. She then sets the fikiwatasi on the mats, and again replenishes, holding her sousou at the bottom with both hands while she is pouring.

As the bride, though previously instructed in the ceremonial, might happen to make some mistake, the kaizoje (Plate 1, fig. 11.) is at hand to prevent it.

§ 62. The male butterfly ought to pay great attention never to pour out till the other has put a little zakki into her sousou; this is all they have to observe.

§ 63. There are also two pans for zakki; one, named naga-je, has a handle; the other, called siosi-fisage, has none; they require more attention when they are used.

§ 64. It is not allowed to snuff the candles at the solemnization of weddings: when the snuffs become too long, fresh candles must be brought.

§ 65. After the marriage ceremony, the fikiwatasi and the sousous are set down before the toko.

§ 66. In the adjoining apartment, there is another woman to bring the simaday (Plate 11, A.); she sets it in the middle, between the toko and the place where the company are seated.

§ 67. As soon as the fikiwatasi is placed before the toko the bridegroom leaves the apartment.

§ 68. After the nuptials, the bride moves back a little, and the kaizoje again places herself at her right.

§ 69. The parents, who were in another room, are informed by the attendant who was on the left of the bride that this ceremony is over; they then remove to the festive apartment.

§ 70. The parents of the bridegroom enter at the same time, and seat themselves in the place destined for the master and mistress of the house, on the left hand, which is the most distinguished, near the bride, whose parents likewise sit in the most elevated part of the room, and near the toko.

§ 71. The bridegroom returns, and places himself on the left of the bride’s mother. (Plate 1, fig. 3).

§ 72. The mediators are seated to the left of the bridegroom. (Plate 1, fig. 4).

§ 73. The two younger brothers are seated on the right hand, which is the less honourable place, of the bride. (Plate 1, fig. 9 and 10). The kaizoje is next to them, but rather farther back. (Plate 1, fig. 11).

§ 74. All being seated, a servant takes the tekaké from before the toko, and presents it in token of welcome to each, beginning with the parents of the bride, then proceeding to the bridegroom and the mediators, afterwards to the parents of the bridegroom, the bride, and the bridegroom’s brothers.

§ 75. The tekaké having been thus presented, is carried to the adjoining room, and deposited in its place.

The tekaké-tanbo is another tray, with a quadrangular supporter, also of wood, but without any circular aperture at the foot; the joinings are fastened with bark of cherry-tree. The tekaké, the fikiwatasi, and the sousous, on the contrary, have on three sides of their supporter a circular hole; the side where there is none, and where the pieces are joined together with cherry-tree bark, is considered as the front.

The person who presents the tekaké lifts it on each side underneath, as the edge must on no account be touched with the fingers.

§ 76. The male butterfly then goes to the toko, takes the fikiwatasi in the same manner, carries it into the second chamber, and returns it to its place.

§ 77. The female butterfly, having taken the sousous in the same manner, follows the others and sits down with them at the entrance of the second chamber, near the sliding groove for the shutters.

The mediator then directs the male butterfly to whom she is to hand the bowl of zakki; she immediately places the fikiwatasi before him, and fetches her sousou. We have already explained in § 60 how it is to be held.

The male butterfly seats herself before the fikiwatasi with her sousou; the female butterfly sits down behind her, and every time the first has to replenish, she pours a little zakki into her sousou. Each of the company drinks three times; when one has drunk he sets down the bowl on the fikiwatasi, and the mediator by a gesture, indicates to the male butterfly to whom she must next hand it. She holds her sousou in her left hand, passes the right through the hole in the foot of the fikiwatasi, and thus presents it, held on the open hand, to one after another. The manner of pouring out and drinking has been already described.

The female butterfly constantly follows the male, who, holding her sousou in her left hand, and the tray on the palm of her right, must pay great attention to turn always to the left; a circumstance which the other must likewise observe.

To convey a more correct idea of this, let the company be supposed to be seated in the manner represented in plate 1. When the male butterfly has to carry the bowl from the master of the house to the father of the bride, she turns to the left, and sets down the fikiwatasi before him; if she has to present it to the bridegroom, she turns to the left, and advancing sets it down before him; but, if his father offers it to the bride, she makes a circuit to the left, passes before the bridegroom’s parents, and sets down the tray before the bride: if the master of the house offers the bowl to some one on his right, or to any of the persons who are opposite to him, she must still take care to turn to the left.

§ 78. The company being supposed to consist of the persons above-mentioned, they are seated in the following manner:

In the most distinguished place of the apartment (plate 1, a), is the toko; next to it, fig. 1, the father of the bride; 2, her mother; 3, the bridegroom; 4, the mediator; 5, his wife.

Opposite to the most distinguished place, fig. 6, the master of the house; 7, his wife; 8, the bride; 9 and 10, the bridegroom’s brothers.

§ 79. The following refreshments are provided for the occasion:

In the first place, what is on the tekaké, on the fikiwatasi and in the sousous, then soni and soeimono soups, in covered terrines, each on a very small salver; then is brought a tray of a white colour, called osiday, on which is a representation of a tortoise, from whose back rise several kinds of ornaments appropriate to joyful occasions, as fir-trees, plum-trees, bamboos, rocks, &c. (See Plate 11, B). Various kinds of confectionary and several little boxes of dainties are also set upon it. Each person is then presented with the tray fonzen, upon which are a dish of fish, pulse, and carrots, called namasou, a bowl of boiled rice, another bowl with a cover, containing miso soup, made of fish, pulse, and carrots; and a small tray of konnemon (a kind of cucumbers pickled in zakki grounds). The wood of this tray is planed as thin as paper, and is called wousouita. A firasara, a small, low, circular terrine with a cover, containing different articles, is presented to each person. It is set beside the tray fonzen: a large dish of bream, broiled with salt, is then served up, and that is followed by covered bowls with soup of wild ducks, rock-leech, fish, pulse, yolk of eggs, and a plate of small pilchards, and sea-lentil.

After this comes the apparatus for zakki; each having drunk once, boiled sea-spider is served up, and then zakki again: afterwards comes the founa-mori, composed of the flesh of the lobster, representing that shell-fish lying on its back, and forming a sort of pyramid. After each person has drunk a third time, he is supplied with a small plate of fresh tripangs with ginger sauce: they then drink again, and this is followed by a sigi-famori, or imitation of a snipe, formed of the flesh of that bird, and shaped in the same manner as the lobster. After the company have drunk the fifth time, fishes’ roes are brought. These are succeeded by several sorts of sweet-meats, a piece of nosi (dried rock-leech), kobou (fresh rock-leech), sea-lentils, and lastly cups of zinrak (powdered green tea), prepared with boiling water.

Many points are to be observed in preparing and carving these various dishes.

§ 80. The mediator must take care to make himself thoroughly acquainted with the manner of contracting relationship. To prevent mistakes, a list is prepared folded like a fan, and called taki-naga, on which are written the initials of the names of the company. This list the mediator holds in his left hand, and points out to the male butterfly the person to whom she is to offer the daki or kawaraki, earthen bowls used at weddings, in imitation of the practice followed at the court of the Daïri, whose food, both dry and liquid, is every day served up in fresh dishes of earthenware, emblematical of the simple mode of life of his ancestors. As every thing that he has once used is destroyed, it is fortunate for the Djogoun, who is obliged to defray all the Daïri’s expenses, that these utensils are only of earth. The origin of the kawaraki bowls is explained in the fabulous chronology prefixed to my Chronology of the Chinese and Japanese; where it is stated, that Zin-mou-ten-o, the first Daïri, caused earth to be brought from the mountain of Ama-no-kakoui-e-jama, for the purpose of making kawaraki, to be used for invoking the gods of heaven and earth.

When the bowl is carried to the mediator, he puts the list beside it, and to avoid all mistake, he lays his fan by the name of the person who is to drink: this is one of the duties attached to his office.

§ 81. Let us suppose that the company consists of the under-mentioned persons, who are distinguished in plate 1 by numbers, as follows:

- 1. The bride’s father.

- 2. Her mother.

- 3. The bridegroom.

- 4. The mediator.

- 5. His wife.

- 6. The bridegroom’s father.

- 7. His mother.

- 8. The bride.

- 9. The elder of the bridegroom’s two brothers.

- 10. His younger brother.

The mediator first sends the bowl to the bridegroom’s father, or to No. 6, from him to 1, from 1 to 7, from 7 to 4, and thus follows the whole series of numbers, which is scrupulously given in the Chinese work, but would be superfluous here: suffice it to observe, that this long ceremony concludes as it began, with the father of the bridegroom.

Here the marriage ceremony preceded, and is followed by the contract of relationship, to prevent confusion.

§ 82. Sometimes the marriage and the contract of relationship take place at once. It will be seen below how they proceed in this case.

During this ceremony the whole company sit quite still, without speaking a word; the mediator alone intimating by signs to the male butterfly the person to whom she is to present the bowl. She begins with the father of the bridegroom, or No. 6, goes from 6 to 1, from 1 to 7, from 7 to 8: the engagement is then made between 8 and 3, or between the bridegroom and the bride, each of them drinking thrice three times, in the manner described in section 60; which done, the bowl again passes from 8 to 3, then from 3 to 4, constantly following an order of numbers marked in the Japanese original. The ceremony finishes between 1 and 6; that is, between the father of the bride, and the father of the bridegroom.

When this method is intended to be adopted among the lower classes, the mediator must previously study his part with the greatest attention. To prevent mistakes, he has the initials of the name of each guest written down in his list, in the order in which he is to drink.

§ 83. After the conclusion of the contract of relationship, the male butterfly takes up her sousou in her right hand, passes her left through the aperture in the foot of the fikiwatasi, and thus carries it on the palm of her hand into the adjoining room, where she puts it in its former place by the side of the tekaké. The female butterfly follows with her sousou; the two butterflies set their sousous on the waiter which is placed by the fikiwatasi, so that the sousous are as before quite close to one another.

§ 84. Whether the wedding is held at the house of the bridegroom’s father, or at that of the bride’s father, the room adjoining to the apartment prepared for the ceremony is separated from it by sliding shutters, that the guests may not see what is passing in the latter. Behind these shutters is stationed a man in a kami-simo, or complete dress of ceremony, (Plate 1, fig. 14), which has been described in a note to the Ceremonies observed at the Court of the Djogoun, in the course of the year; or a woman in her dress of ceremony, called woetje-kake, flowing robe with a long train. Both of them must be well acquainted with all the formalities connected with weddings. It is their business to pay the greatest attention to all that passes, and to give the necessary instructions to the other servants.

§ 85. The contract of relationship being concluded, the bridegroom’s father congratulates the company upon it, and each of the others does the same.

§ 86. Three varnished zakki bowls, one within another, are then brought upon an ordinary waiter, which is placed in the honourable part of the room near the candlestick.

§ 87. A present from the bride is now brought to the residence of the bridegroom: it is delivered by a female, who is deemed clever at turning the accustomed compliment. She lays it down with the list in the room next to that in which the company are assembled, arranges each article separately, and hands the list to the mediator: he transmits it to the bridegroom’s father, who lays it by his side, returns thanks, and after reading it, again expresses his thanks.

§ 88. The names of the bridegroom’s parents and brothers are written on the same list, which also specifies the present destined for each of them.

If the near relations are too numerous, a second list is made for their names and presents.

A separate list is made for the servants of the first and second class: the same is likewise done in regard to those of the third class, who are presented with strings of sepikkes.

It is a mark of distinction to make these lists. The present is delivered to each of the near relations on a separate tray.

§ 89. This and the next section describe the articles composing the presents, and how the lists of them should be made out, under the letters D, E, F, and G.

| D. | a. | The list of presents for the bridegroom. |

| b. | Two robes. | |

| c. | A belt or girdle. | |

| d. | A dress of ceremony. | |

| e. | A fan. | |