Heresies of Sea Power/Part 1/Chapter 5

V

THE SPANISH ARMADA

The incident of the Spanish Armada falls somewhat into line with the Athenian expedition to Syracuse, with the invasions of Africa in the Punic Wars conducted by Regulus and Scipio, the invasion of the Crimea in 1854, and—though to a limited extent—with the effort of the Baltic Fleet in the Russo-Japanese War.

Conditions and details naturally vary— thus the Baltic Fleet carried no military force; but in each case there was the same underlying principle; the aggressors advanced trusting in a naval superiority. Some of the instances mentioned have been used to illustrate the doctrine that invasion is impossible in face of an unbeaten fleet, but success or failure would seem to have rested more upon the actual power of the aggressors as opposed to their presumed power. The Spanish Armada, had it possessed the superiority that its sender believed it to possess, need not necessarily have failed because English ships held the narrow seas. Its cardinal error lay rather in Philip's inability to realise the magnitude of his task, and his neglect to provide the power necessary to accomplish it.

The invasion of England was at the time of the Armada a classical idea in Spain. First mooted by the Duke of Alva in 1569, it was revived by the Marquis of Santa Cruz in 1583 after the battle of Tercera. Some ships which ran away in this action were believed to have been English, and the impression was general that the English, whether on land or sea, were easily to be defeated by a firm front.

When the Armada idea first completely materialised in 1586 Santa Cruz had formed very complete plans which allowed of the employment of 556 ships and a total of 94,222 men.[1] Whether this force would have succeeded need not here be discussed, because Philip did not put the plan into operation. The plan actually adopted, though extensive, was on a considerably smaller scale. In brief, Santa Cruz was to take into the Channel a fleet sufficient to destroy the English fleet, and under cover of this Parma was to transport the Spanish army in the Netherlands to England in flat-bottomed boats. Substantially the scheme was not very different from that of Napoleon at a later era, nor did it differ so very materially from the successful invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066. In each case naval superiority in English waters was understood to be a necessity to success.

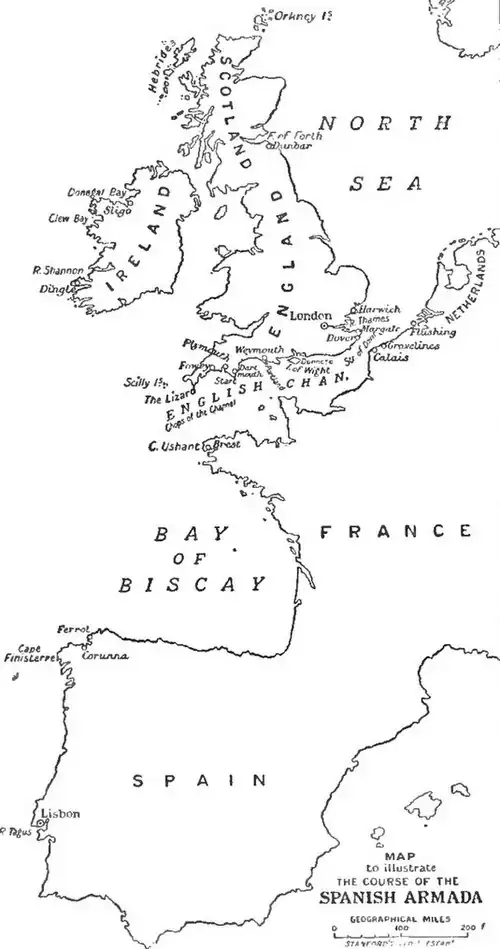

The invasion was delayed by the operations of

Map to illustrate the Course of the Spanish Armada.

Drake, who destroyed many Spanish ships while they were yet unequipped, and early in 1588 Santa Cruz died. Medina Sidonia was appointed in his stead, despite his protestations of lack of the necessary experience.

He sailed at the end of May with 130 ships and a total of 30,493 men, a force far inferior to the original Santa Cruz estimate, though, so far as soldiers were concerned, troops from the Netherlands were destined to bring it up to something like the Santa Cruz figure. The lessened number of troops to be transported from Spain reduced the number of ships, for the original estimate embodies 150 'great ships of war'[2] besides many lesser warships, whereas the whole total of Medina Sidonia's force was only about 130 ships of all sorts, and of these several came to grief on the way. Professor Laughton estimates the outside numbers that reached the Channel as under 120 ships and 24,000 men. Of these not more than sixty-two were fighting ships, several of which were but very lightly armed. The Annunciada, for instance, carried but three 18-pounders and three 9-pounders in the way of medium-sized guns, and several others were proportionately feeble.[3] The same authority places the English fleet at forty-nine vessels, a few of them quite as large as the Spaniards in tonnage, though of less freeboard. The English ships carried many more heavy guns than the Spaniards as a rule, had altogether

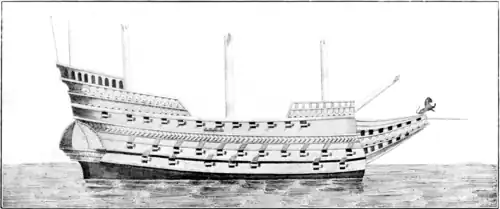

SHIP OF THE SPANISH ARMADA.

SHIP OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR. (See p. 282).

better gunners, and (an important point) ports that admitted of far better training of the guns. The English were also altogether better seamen, and their ships infinitely more handy, so that, despite the numerical inferiority of the English, the Spaniards never had that certain naval superiority which was a cardinal feature both of Santa Cruz's first plan and of the modified plan finally adopted. The Spaniards, indeed, had nothing in their favour except bulk and the prestige of Spain. There is no reason to believe that this prestige had the slightest effect upon the 18,000 men odd who manned the English fleet, whatever opinions may have obtained on shore. Drake and his fellows were well used to conflicts with the Spaniards.

The Spanish fleet, though it carried a very inadequate supply of ammunition and stores, was not altogether so ill prepared as its fate might suggest. Medina Sidonia's instructions specially referred to the English superiority in guns and gunnery and directed him to engage at close quarters.[4] In this way the high poops and forecastles could be used to deliver a deadly small-arm fire upon the English decks, and upon this the Spaniards seem to have relied, as in the first action on Sunday, June 21, all their efforts were directed to a vain attempt to close. But if the Spaniards failed in this, their bulk saved them from any very serious loss, and when the Armada reached Calais on the 27th it had only lost three large ships.

At Calais communication was opened with Parma, who, however, was unable to co-operate, since his flatbottomed craft were all blockaded at Dunkirk and Newport by the Dutch. This fact rendered the invasion of England impossible; as the Spaniards could in no way raise the blockade in face of the English fleet without first beating that fleet.

The next night fireships were sent into the Spanish fleet and on the following morning, June 29 the battle of Gravelines was fought. It lasted from nine till six at night, at which time the Armada mauled and shattered bore away to the northwards, pursued by the victorious English. Its exact loss of ships in the battle was not, however, very great—only some seven ships being actually destroyed. The remainder, unable to return by the Straits of Dover essayed a course home by the north of Scotland, where the majority of them perished by wreck and storm.

Stripped of its romance, the failure of the Armada is no conclusive proof that its conception was a great strategical error. Had it been on the lines first conceived by Santa Cruz, carrying all the necessary soldiers instead of having to go to the Netherlands for them, it is difficult to prove from the results of the early fights in the Channel, that it could not have

BRITISH SHIP AT THE TIME OF THE SPANISH ARMADA. From Fincham.

occupied the Isle of Wight or effected a landing at a dozen other spots upon the south coast of England. From what we know of Santa Cruz there is no reason to believe that he would have attempted to use it so ill-found as it actually was; and had it been less ill-found, had it not run out of ammunition, had it been properly handled, the English plight would have been undoubtedly serious. Its own utter failure is proof that it failed; but it is less clear that it proves invasion in face of a fleet to have been impossible in the sixteenth century when invaders lived upon the country invaded in ways impossible to-day. Scipio Africanus invaded Africa and reduced Carthage to sue for peace in face of a defending fleet which once at least attacked him with some success. Coming to more recent events the Allies invaded the Crimea in face of a fleet which, had it only acted as the English acted against the Armada, might or might not have reproduced the Elizabethan tragedy. It made no attempt to do so—Russian imagination being overwhelmed by the magnitude of the oversea expedition of the Allies, or else, as has been suggested elsewhere in this book, because the Russians elected to fight the issue on land. In any case, an oversea operation bearing a remarkable likeness to the Spanish Armada in its general conception—that is to say, attack by a very powerful naval force without any previous attempt to secure the command of the sea, was undertaken and succeeded.

The conception involved in the move of the Baltic Fleet to the Far East in the war of 1904–5 was very like that of the Spanish Armada as it actually occurred. The Russian fleet was numerically very powerful. Unlike the Spanish Armada it had no transports with it, but its many store-ships formed something of an equivalent.

It had more conceptions as to the orthodox theory of Sea Power than had the Spaniards: that is to say its definite object[5] was to defeat the Japanese fleet, cut off the invading army in Manchuria and so reduce it to defeat or surrender from lack of supplies, and then at some future date convey an invading army of Russians to Japan. In this last, its objective was very similar to Medina Sidonia's—an army was to be picked up near the scene of conflict, and a defending fleet existed—conditions which have obtained in countless wars, in fact in every war in which both sides have had ships and either has attempted oversea operations.

The end of the Baltic Fleet was destruction, more complete and absolute than that of the Spanish Armada, but in both cases the most obvious cause of destruction was that the force employed was insufficient for the particular task before it. Had Rogestvensky been a Scipio Africanus, had the Japanese fleet been no more enterprising than the Russian ships in the Crimean War success was quite possible—in the light of these parallels nothing was wanting save fitness to win.

With sufficient fitness to win, that is to say with crews individually superior to the Japanese, Rogestvensky would have won with the ships at his disposal, and Medina Sidonia, had he and his men been all that they were not, would also have won in all probability. The causes of defeat surely lay elsewhere than in the ships or strategies: or how shall we explain the success of Scipio Africanus's armada against greater odds? In all the history of such failures is written the way that might have led to success, or rather the things without which success is impossible. It is a platitude to say that the Spanish Armada would have succeeded had it been the fitter to win, but history conveys very little lesson beyond that its failure was due to lack of this fitness. Whatever its relative inferiority in heavy guns cost the Spanish Armada, its inability to use effectively such guns as it had, and to secure sufficient ammunition for them—both personnel matters—cost it a great deal more. Whatever Spanish ships lost from being unable to close with the English, technical inability to manœuvre to do so—a personnel thing again—cost still more. In the Great War with France slower English ships time and time again brought swifter and handier Frenchmen to battle; and Drake's men in the Spanish ships fighting Sidonia's in the English ones would in all probability have succeeded in compelling close quarters by virtue of fitness to win. Indeed, the probabilities are that they would have destroyed the English fleet far more effectually than they destroyed the Spanish. If this be admitted (and to avoid admitting it is difficult) how can we trace the defeat of the Spanish Armada to anything having to do with ships or strategies or any of that ignoring of these 'principles of war' of which it is always made an object lesson?

- ↑ La Armada Invincible, Duro.

- ↑ Duro.

- ↑ Laughton.

- ↑ Duro. ... It is of interest to note here that Rogestvensky appears to have received ' special instructions ' with a view to neutralising Japan's salient known superiorities. ' Keep everything together ' seems to have been the one great maxim (perhaps the only one) of the Baltic Armada.

- ↑ Presumably its object—Admiral Nebogatoff (Fighting Ships, 1906) proves clearly that had evasion been desired there was nothing to prevent the La Pérouse passage being selected; whence it is to be inferred that Eogestvensky selected the Tsushima passage with a view to fighting there. Nebogatoff proves quite clearly that the idea that coal scarcity compelled Tsushima is purely fanciful.