Greenland by the Polar Sea/Chapter 9

JULY 3rd-14th.—After two fickle months the weather at last settled down, a change which apparently will last. through this month, fortunately for us! For after every day's journey, during which with great toil we cover a modest distance of 15 to 16 kilometres in twelve to eighteen hours, all our clothes and goods need a good drying, and this could not be managed if the good sun did not during our nightly sleep once more make serviceable everything which the distracting summer conditions of the ice destroys for us.

The journey goes through ice-water, and it is only occasionally that we have an opportunity of a moment's rest on "dry ice." The warmth has converted the rough Polar-ice into a hopeless system of channels and pools, wherefrom occasional blocks push up as islands in a huge swamp of ice. In the beginning we sought obstinately for the best places where a zigzag advance was possible; but this method has been given up long ago, for everything is wet through in spite of all our efforts. All through the day we wade up to our knees in the ice-water, and, whilst we get wet through to our waists under the work with the sledges, which constantly get stuck in the holes, the same fate overtakes our reserve clothes. First the water pours over the sledges in front, then behind, according to the different positions it occupies in the melted hollows.

We have crawled in this way for three days—from Centrum Island to McMillan Valley by the mouth of Victoria Fjord—a three-days-long bath in the cold water, often covered thinly by new ice which cuts the paws of the dogs as it breaks into knife-edged fragments. The cold water takes it out of those of the dogs which have not yet quite recovered from their period of starvation; to our great sorrow, we have had to leave one dog which was so exhausted that it fell down unable to get up again.

When neither we nor the dogs could move a step further, we select an ice-island and pitch our tent on it. A place like this can never be an ideal spot for a tent, but there is the comfort that one need not trouble to go far to fetch the water one needs for cooking. One merely opens the tent-flap slightly and fills kettle and pan.

Under these somewhat cheerless conditions, Koch celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday. We hoisted the flags, both the Danish and the Swedish, and made an extra cup of strong coffee. Each of us then presented the hero of the day with a few lumps of icing sugar—a much appreciated and, at present, exceedingly valuable article. The last of the store of this sugar put aside for the homeward journey across the inland-ice has been distributed in rations and everybody watches as a beast of prey over his modest share. We might have had a feast, but I sheered off from the festive feelings of the moment for rational reasons. We are the possessors of delicious pemmican, oats and biscuits; but these delicacies must only be touched when the journey on the inland-ice commences. In that desert we shall require all dietetic stimulants. In spite of temptation, I therefore hardened my heart and contented myself by cooking double rations of seal meat, and, at the same time, I promised faithfully to celebrate the day when, on the return journey, we had reached to a height of 2,000 metres on the inland-ice.

The short and slow daily journeys benefited the cartographer, who took latitudes and longitudes, sighting all the more conspicuous points as often as occasion permitted.

During a halt, approximately 13 kilometres from McMillan Valley, the coast was carefully surveyed with the glasses. We looked for hares, which were now visible far away as tiny white dots. Our store of meat was finished and we found no seals on this bad water-filled ice. Bosun and I were somewhat behind, engaged in lashing our sledge afresh. As is well known, all transoms are tied to the runners with leather straps, and when these are immersed in water too long, they soften and give so that the lashings loosen and the whole sledge falls to pieces-as a rule, of course, where the water is deepest! To lash a sledge takes an hour's time and is laborious and tedious work, especially so when the hands are numb.

Whilst we were bent over the unloaded sledge, and struggled to tighten the wet straps, which were difficult to handle, new life was suddenly put into the crowd ahead. They had been lying tired and dead on the sledges, but now they began to jump about like mad, and both Harrigan and Ajako ran far out to the side, jumped high into the air, flung their arms about and slapped their thighs, all of which are Eskimo signs of some unusual happening.

Bosun and I looked at each other for a moment incredulously, without saying a word; for this could mean one thing only. But as we stood there staring, not quite daring to believe that for which we had hoped more than anything else, Bosun sensibly delivered himself of the relieving sentence:

"One does not cheat hungry and wet comrades who are toiling ahead through the water!"

In the same moment we both gave vent to a bellowing shout:

"Musk-oxen!"

The sledge was finished in a twinkling, and as rapidly as the bad going permitted we were up on the ice after our comrades.

All faces beamed; what we had guessed was really true. We ourselves took the glasses to see. Off a small glacier tongue in McMillan Valley, on a ridge towards our old spring camp, a herd of grazing musk-oxen was plainly visible.

We embraced each other and behaved like lunatics. No dignity here! For what we saw meant not merely food in plenty for ourselves and the dogs, but also implied rest and drying of our clothes for some days in the beautiful valley, which must now be in its full summer garments.

With great difficulty we covered the last piece of the way; under favourable conditions it would have been done in an hour, now it took seven, before at last we beached with dripping clothes after a thorough bath of thirteen hours' duration.

I arrived an hour after the others, as the sledge for the second time during the day had fallen to pieces and had to be lashed afresh. My comrades had already pulled off their wet clothes and were taking sun-baths stark naked on a small grassy slope. And surely this was necessary, for we were red and wrinkled right up to our waists just as if for a long time we had been in soak. The temperature here on land was perfectly tropical, showing 5° (Cent.).

I was hoarse with shouting to the dogs, which for the last stretch had been almost impossible to drive through the water; and Dr. Wulff came smilingly towards me and told me that during the hour whilst they had been waiting for me, he had experienced the truth of the word of the holy Augustine: That the joy of the blessed consists not merely in knowing oneself to be on the right side, but also, and that not least, in the constant listening to the despairing cries of the damned." Thus they on land had felt it, after having fought their way to the right side, when they heard me out in the slush alternately yammering and raging at the dogs!

We were all hungry as wolves and therefore voted for an immediate hunt. So we went across the land, taking all the dogs with us. Unfortunately, we were stopped about half an hour later by a flood-like river about 400 metres broad, and after having made several desperate attempts to ford it we had to postpone the hunt until the following day, as the river could only be passed some distance seaward out on the ice. In spite of our hunger and murderous instincts, not one of us was to-day in possession of sufficient courage to cross this ice just as we had reached land.

To stave off the hunger, we arranged a hare-hunt, which gave an excellent result. In the course of a couple of hours no less than eight of the little white-clad animals had to lay down their lives, and a temporary camp was made so that we might have a little rest before the musk-ox hunting started in earnest.

The wet clothes were spread out to dry, and we dozed off half naked in the most varied postures, not unlike a horde of Serbian refugees, with all our earthly property distributed about us.

After five short hours of rest we again went seaward on the ice, navigating between and through a complex of deep channels by the mouth of the great river, it being our intention to attempt a landing a few kilometres due east of the main course. The ice here was particularly bad to walk on; the whole surface was so far melted that everywhere it had taken on the character of an expanse with thousands of nails side by side turning their points upward. The tracks of the dogs were red with blood after the many awls which found their way into the pads of their paws, and even we men felt the pain through our soaked boots. With a feeling of relief we at length reached land and pitched our tent in a small sheltered cove by a kindly bubbling brook. Sledges and goods were deposited up on land, and as soon as all our wet clothes had been put out on the cliffs to dry, we took the course up a mountain and into the valley where yesterday we had seen the musk-oxen. We brought all the dogs so that they might be as near the slaughter-ground as possible.

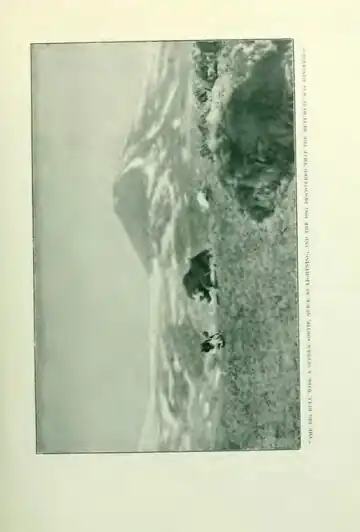

After an hour's walk we got a view across a low ridge, and hardly had I had time to examine the surrounding district when instantly and simultaneously we all gave a start. A little more than 100 metres from us five musk-oxen were peacefully grazing, unsuspicious of the beasts of prey who had been counting on their death for the last twenty-four hours. All the dogs with the exception of two were carefully tied to some big stones before they got wind of this fragrant game. For if the dogs are loosed in a flock on a musk-ox, especially if they are hungry, they will as a rule throw themselves so recklessly and greedily over their prey, that one runs the risk of having them gored; and at that moment we certainly could not afford to lose more dogs. We therefore contented ourselves with taking the two poorest ones, and walked along to the herd. We divided into three parties, and before the musk-oxen had discovered us, we stood before them on three sides as if shot up from the ground.

The musk-oxen lay ruminating; they now arose without haste and took up their usual fighting position, the famous square with a front to all sides. Thus they remained standing without making the slightest attempt at flight, whilst we on our side had the greatest difficulty in holding back the two wolfdogs, which wanted to spring on to them.

There were five bulls, and they all accepted the position with dignified calmness; their great shiny eyes stared at us without fear, and they contented themselves with an occasional almost contemptuous twist of the corners of their mouths.

To us they seemed phantastical in their enormous size, because for such a long time we had been used to the sight of hares and lemmings only. They were in the midst of shedding their coats, and the loose wool, which appears to come off in big cakes, lay across the manes and backs as bunches of mourning crêpe. Occasionally they breathed deeply through their enormous nostrils, and blew wheezingly out into the air. Then they would, as if in impatience, beat a hoof against the soil so that small stones flew about our ears. Otherwise they remained quiet, making no attempt to attack.

As the rare and occasional hunts had given us no good opportunity for photography, all the three of us—Koch, Wulff and myself took our position and snapped. More patient clients no photographer could have wished for, notwithstanding the fact that we did our work very thoroughly. We took them from all sides and angles, from a distance of from 2 to 10 metres, profile, full-face, whole-figure, half-length, and only when we had finished did we pass sentence of death.

First we made an attempt to drive them further down towards the tent, so that it would be easier for us to carry the meat down to the sea-ice. We went, still with the dogs on leash, close up and began to throw stones at them. At first they seemed surprised and indignant over this treatment, which appeared to them most unworthy; but then the devil took possession of them!

The biggest of the bulls, apparently the leader, suddenly stamped his hind hoofs so hard into the soil that a rain of gravel and stones fell over us; then he let out a bellow, turned right about and galloped across the plain with the remainder of the herd behind him.

We unleashed the dogs immediately, and they tore after the oxen; but the whole proceeding had taken place with such lightning swiftness that the bulls had got a good start, and it took the dogs some time to draw close to them. We ran with all speed, so as to be near and ready to shoot when at length the drive would stop on the top of a hill where they could defend themselves against the attack of the dogs.

But things did not work out according to plan. The bulls ran for dear life, and they made such a pace that it almost looked as if they were blown along by a hurricane. Right out by the end of the plain the foremost of my dogs succeeded in overtaking the herd. We saw it attempt to bite itself fast on to the hind leg of the rear fighter; but instead of stopping at once, collecting its comrades in a square and receiving the attack, the bull, with the dog yet hanging with teeth buried in its flesh, was content to turn round with lightning quickness, shake the dog off, scoop it with its horns on to its enormous neck, and fling it up in the air like a ball. The poor dog whirled round and crashed heavily to earth; its courage cost it its life.

In the meantime the hunt raged on. The other dog, which was an old and experienced bear-dog, had come up with the fleeing herd and succeeded in stopping the hindmost ox outside a steep high cleft. Ajako, who was ahead of us all, rushed up ready to shoot, but in the moment he raised his gun, the bull threw itself down over him like a landslide, paying no attention to the scolding dog, which in vain tried to hold it back. They disappeared together into the cleft, and I only saw the cloud of sand and gravel which whirled up round them. I rushed up as quickly as I could, and to my great joy I soon heard a shot, then another, and a moment later I myself was down on the battleground. Ajako, his face yet aglow with excitement, stood by the killed bull, whose dreadful and sudden attack so nearly had cost him his life.

The four remaining bulls ran in close formation up a hill, where they passed close by our tethered dogs. These rose up and commenced an infuriated barking, whereafter the bulls, obviously bewildered by the many wolves, once more changed their direction towards the river to the south-west.

One duffer, who could not keep up with the others, separated from the herd and galloped towards the lake where we had camped during the spring. After a hot chase, it was overtaken here and stopped by two dogs which had torn themselves loose. Whilst they held it Bosun arrived and shot it down.

The remaining three gained their freedom for the time being, but although we were sure that it was only a matter of time when we should find them again, we nevertheless repented too late our stone-throwing; for it would surely have been better for the transport to have the animals collected in one place. For the moment we had to be contented with the humour of having photographed them at a distance of a few metres, and then in spite of our need for meat, to lose them! It is the first time during my many musk-ox hunts that I have seen an attacked herd which has not stopped and formed square after a short run, to meet their inevitable death.

The two musk-oxen were skinned; and we all ate fat marrow-bones until we were in that peaceful mood which follows on a good meal. We could not deny that our joy was mixed with bitterness, for three big, lovely animals had temporarily escaped out of the flock which we had reckoned on with such surety as a foundation for a couple of restful days in the beautiful and summerlike McMillan Valley.

We were all agreed that something must be done; both we and the dogs needed a rest before we had to wade on across the broad Sherard Osborne Fjord. In the meantime we had already had a turn of over thirty hours under very severe conditions; then, after a few hours of sleep, we had again been keenly active for rather more than fourteen hours; nevertheless, it was desirable that the hunt of the three musk-oxen should be continued at once, before they got too far away.

We were all sleepy and tired. Whilst in the cleft the last meal was cooking, one after another drooped down and slept. The many days' bath in the cold ice-water had not passed over us without leaving its mark; some of us had in a most uncomfortable way lost the powers of the knee-muscles, and to-day especially Harrigan and I had sunk to our knees time after time during the musk-ox hunt when we ran down the slopes, for we had no strength in the muscles of our legs.

Under these conditions there was only one man on whom I could count, and that was the best and indefatigable hunter, Ajako. Time after time I have had the opportunity to emphasize his invaluable qualities for a voyage like this; his splendid physique, his endurance, his never-failing hunter's instinct. He it was who shot the first musk-ox at a time when the position began to be critical for the dogs; he it was who caught the first seals by the whirlpool and saved the rest of our team; and, finally, it was he who in the midst of the Polar pack-ice off Cape Neumeyer got the seal which secured the voyage to de Long Fjord. Therefore it was also this man whom I suggested should continue the hunt at a time when the rest of us had to give in because of overstrain; and the hunting excursion he was to undertake would take at least another fourteen hours. Ajako accepted my proposal with a smile: oh yes, it had been his own opinion the whole time that it would be better to continue the hunt at once; thus the matter was settled. As soon as the contents of the pan were cooked, we turned out on a big flat stone delicious pieces of tongues and hearts, floating in fat, and had our meal together. Then Ajako seized his gun, loosened the dog which usually followed him on all his hunting excursions, and disappeared behind the nearest ridge, light and supple, as if he had just got up from a long and refreshing rest. Over his walk and all his being rested a beauty which only youth and strength gives.

Twelve hours later Ajako returned to the tent tottering with sleepiness. Not only had he found and shot the three oxen which had tried to escape: he had also shot another three. All the animals were skinned and cut up, and the meat had been laid out in the sun to dry, so that it might not be destroyed by the bluebottles which shoot up from the soil everywhere in the vicinity of a piece of meat.

To these good tidings he added smilingly that he had also seen another herd of six musk-oxen, peacefully grazing near his slaughter-ground, undisturbed by the hunt. These last animals he judged it best to let live until the camp had been moved nearer to that spot.

To crown it all, he carried on his back, in addition to the hearts and tongues of the newly-killed animals, two delicious barnacle-geese which he had shot near to our tent on his way home.

He honestly deserved the twenty-four hours' sleep he had after this excursion.

Later on we moved the camp 10 kilometres ahead to a valley in the vicinity of Cape May, off the point where both the killed and the living oxen were found. We set out in glorious sunshine, and the good warmth which, during the last few days on land, had baked right through our bodies, which were often quite red and swollen after our wading trips, gave us new strength for the coming toil. And that was urgently required, for it took fifteen hours to cover the 10 kilometres through water, ice-rivers, and rugged Polar-ice. We made ready for the hunt when we had pitched our tent by the sea-ice.

We were now able to face the coming week with calm minds. There was a sufficiency of meat for men and dogs, and plenty of work for the botanist of the expedition in the fertile, well-watered valley.

For the first time during our journey we all had real feelings of summer with 7° (Cent.), and fine, calm, clear weather; that was why we called the valley with the name which sounds so sweetly to an Arctic traveller, Summer Valley.

July 11th-14th.—As soon as our clothes were once more fit to use after the wading trip of the previous day, we all went into the mountains with the dogs leashed; they were to go "into the country" for four days to regain their strength, and during that time they would be allowed to eat as much of solid meat as they could get down; they were to laze, gorge, and grow fat.

To the uninitiated it may perhaps seem that sledge travellers are inconsiderate and cruel to their animals. Maybe that now and then we have to harden our hearts towards them when, during heavy going, they throw up the sponge and refuse to proceed; but what else can one do under such circumstances but harden one's heart and force the poor beasts ahead? It is surely to their own interest that we should get them as quickly as possible across bad ground. If a tired dog is cut loose, it will simply lie down on the spot to die without making any attempt to follow. And even if now and then we do treat our dogs harshly—under conditions when we ourselves are no better off—nobody is more happy than we are when for a period we are able to give the faithful animals a holiday and leave them to enjoy the pleasures of the present in excessive gourmandizing. So we then select a well-watered and sheltered place for them, preferably by a small brook with fertile and soft ground along its banks; here all their food is brought to them and they have full compensation for all the evil days we have forced them to live through.

Unfortunately such days appear only as oases in a desert, where generally one must fight for existence from day to day. But then no driver shirks the longest and most strenuous hunt to procure game; and if hunting fails, he will as a rule share with his team the crumbs destined for his own pot.

Our eighteen dogs, then, the remains of the seventy with which we arrived up here, were to spend a few days in lazy abundance, wherefore they were taken up into Summer Valley to a place where Ajako had his meat depot of the six oxen. First, however, the last observed herd was to be killed, and we now found that it consisted of five animals instead of six, as we had originally assumed.

The hunt was quick and easy. The musk-oxen, one bull and four cows, grazed on a fertile hill near to the killed animals. By way of a small valley we had approached unseen by then, and we now stood before them suddenly and without warning. As soon as they discovered us they gathered and formed into their famous order of battle, in no way appearing to be surprised or impressed. They quite calmly looked into our eyes and contented themselves by occasionally sharpening their horns against the stones.

A herd of wild cattle like this possesses a most impressive dignity; not for a moment does their calm ruminating balance desert them as long as the onlooker keeps quiet. They show not the slightest sign of fear as does other game of the wilderness, such as the bear or the reindeer, which run away at a long distance. To run across a musk-ox means really to meet it; it remains quietly standing, examining and scanning us, but over our meeting there is a certain equality, a silent dignity, which almost bears the stamp of an audience in the midst of the great silent waste where no other sound is known than the rush of the rivers and the scream of birds.

They do not suspect, these black, long-haired majesties, that two-legged knick-knacks like us carry such mean devilment as quick-firing machine-guns, nor that all the wolf-dogs, which in the beginning we considerately kept back, will be urged on to them as soon as they attempt to retire from our obtrusive presence.

As usual, we wish to start by photographing them, but this did not fall in with the wish of the bull. He made a few lightning-swift sallies, so sudden and dangerous that we quickly had to shoot him so that we might photograph his wives in peace. When this was finished these also had to bite the dust; and I must say that they accepted death with the same contempt for pain as did the great bull. A bullet through the chest, and they sink to their knees once more staring at us with their large unfathomable eyes, as if protesting against the deceitfulness of wounding an enemy at a distance instead of during a close fight. Then they quiver in pain, until another bullet cuts off their breath and their enormous bodies topple over in the sand, drawing with a heavy gasp their last sigh.

When the skinning was finished the dogs were given as much meat as they would eat; they were then tethered on the selected spot by a running brook, where they could sink into a comfortable sleep until once more they were ready for a meal.

After that we ourselves went down to the tent to take our rest, no less deserved. Every man carried on his back as much of solid meat as he could manage. For we humans have at any rate that advantage over the animals that we offer a thought for the morrow.

We remember Summer Valley as an oasis in our period of distress. It was full summer and at every step we took we could enjoy the many beautiful flowers which pushed up from the mean earth wherever there was the faintest possibility to strike root. Besides these many aesthetic pleasures there was also the material boon of abundant and savoury provisions for so long as our visit lasted.

Summer Valley stretches about 6 kilometres from north to south, or from the sea-ice to the inland-ice. A river, which at our departure will present great difficulties by the great and deep delta which it melts far out in the Polar Sea, has created the valley and flows through 200 metres high hilly tracts, the so-called "stubble mountains," whose slopes are very fertile. From all fells and mountains little brooks run down in the main river, and from certain yet unmelted snowdrifts water oozes down through a throng of yellow, red, white, and blue flowers and lush, green grass.

Whilst at the camp on the ocean-ice we have a temperature which swings between zero and 2° (Cent.), we have 10° of warmth in the shade both night and day as soon as we come a little way up into the valley. In the sun there is upwards of 25°, a temperature so overwhelming that we must search out shady places in order not to suffer too much from the heat.

In strange contrast to this teeming summer is the Polar Sea with its thawing, whitish-grey ice stretching northward as far as the eye can reach.

Snorre mentions somewhere in "Hejmskringla" that Hakon Jarl, during his visit to Harald Gormsön, the King of the Danes, whilst a fugitive from Gunhild's sons, had so much to think about through the winter that he took to his bed. He often lay awake, and ate and drank only sufficient to keep up the strength of his body.

I am on the point of sharing his fate; I have serious problems to consider, and although conditions do not permit me to go to bed to seek the perfect quietness in which the tangled skein may be unravelled, I fully understand the old Viking and his eccentric behaviour. I often lie awake during this period while the others sleep, and it appears to me that one is never nearer to the "pink dawn of decision" than when, with one's body at rest in the sleeping-bag, one's brain is working. Undeniably at this time there is plenty of food for thought for one upon whom rests decision and responsibility.

The bad going of melting ice and water through which we must force our way leads naturally to considerations of the practicability of a summering in this valley where, so far, game seems to abound.

My comrades have repeatedly asked me if I did not consider it wisest to break the journey for the time being, and continue later on when the air was cold enough to freeze the water on the ice. But I have postponed my decision and maintained that we ought to continue so long as we make any advance on even the most modest daily journey.

During the days we have spent here I have thoroughly considered the question and made my decision.

We must continue, and in spite of the demoralizing state of the ground we must make all efforts to reach a point of access to the inland-ice somewhere by the head of St. George Fjord. A summering here might prepare for us the same fate as that which overtook Mylius-Erichsen, for we must rely upon the land-hunting, and, when the neighbourhood is exhausted of game, it will be extremely difficult to reach fresh hunting-grounds. We cannot reckon on catching seals to such an extent that we could feed seven men and eighteen dogs for a period until the going is better, which will hardly be until the beginning of September.

By continuing our journey now, unless misfortune overtakes us, we are able to travel with three teams each consisting of six dogs. At the moment we are all in full strength; but nobody knows in what condition we and our dogs may be after two months of hunting life here.

There is now the hope that we may find seals by Dragon Point, whereas in September we shall find none. Our catch during the summering would have to give such a surplus that, beside our daily needs, we would also be able to provide for the homeward journey; all of which is very doubtful.

Should we postpone the return journey, the difficulties we meet with now would come back on us in another and far more serious way. Later in the year there will be more snow on the inland-ice, consequently our gear and provision will be so inadequate that we must take the route across Fort Conger and make a temporary wintering there. That would complicate our dispositions to a far greater extent.

Now in July and August there will be no unusually low temperature on the inland-ice, we shall have the sun to dry our clothes, and we shall be able to do without our sleeping-bags and suchlike articles, which will considerably reduce our loads.

Even if we should not find very good hunting by Dragon Point, we can safely cross the inland-ice on the provisions which at present we possess; finally, at this time of the year we can cut short our journey and go down on land near Humboldt's Glacier, where hunting of reindeer and hare is good. Later on in the autumn the darkness will deprive us of this chance for hunting.

Last but not least two months of hunting life in these tracts, where necessarily one must traverse huge expanses of land, will wear heavily on our boots, which are already in poor condition because of the constant wading through the water.

Therefore, homeward as quickly as possible in spite of all; every day that goes will increase our difficulties!

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)