Greenland by the Polar Sea/Chapter 7

JUNE 16th-17th.—We now press forward in order to overtake our comrades as soon as possible. We have no time to wait for the coolness of the afternoon, but set off in the sun-warmth of 9.30 on fair ice. The dogs have benefited from the rest and the fat seal meat; with the light sledges they go a good pace if one of us will only walk in front; and so that we may make as much as possible of our opportunity, we decide to try another day's journey of at least 40 kilometres.

After two hours we pass Cape Emory, which juts out in a comparatively low headland with a cleft rich in vegetation, where Ajako shoots a hare and catches a litter of young ones. The surrounding country is an impressive alpine landscape which, snow-covered, precipitous, and with jagged pinnacles, trends in to a narrow fjord.

In a little bay a few kilometres from Cape Neumeyer, we suddenly spy two sledges; we start with amazement and almost lose our breath with excitement when we discover that it is our comrades, who, with a much reduced team of dogs, slowly, very slowly, work their way towards us. Wulff and Harrigan walk in front, whilst Hendrik and Bosun trail behind with the sad remainders of the three teams. We put on extra speed and it does not take many minutes before we meet. It is obvious from their thin, worn faces that they must have had a hard time since last we saw them.

They have hunted in vain for sixteen days, and during this long period they have had to feed exclusively on dog. They are now fleeing for life southward, as it has been impossible for them to reach de Long Fjord. They had been obliged to reduce the number of dogs, and were now driving one team consisting of five dogs, with their baggage wrapped up in a sealskin. The other team of nine dogs was yet able to pull a real sledge. Of the twenty-seven dogs which, distributed among three sledges, left Cape Salor on the 2nd of June, only fourteen remained.

They had made their headquarters at Low Point and continued their hunting excursions from this point right across to Cape Wykander; as, however, they had seen not the slightest sign of musk-ox, they had returned so that they might save the last of the dogs for the homeward journey. They had taken our long absence to indicate that we had succeeded in crossing the inland-ice to Independence Fjord, and as it seemed obvious that they would not be able to find food for the long period of waiting which this would necessitate, they had decided on the homeward journey whilst they were yet in a fair condition and had some of the dogs left.

Considering the bad luck they have had, nothing could be said against this decision; one must act according to one's own judgment under such desperate conditions, and the different parties of an expedition must always, within certain limits, have a free hand so that one does not run the risk of losing everything out of consideration for agreements when presuppositions prove to be incorrect. For all that, I was glad to meet them and to prevent their lonely homeward journey.

We then made camp, and discussed the position during a feast of seal meat, hares, and abundant coffee.

It was essential to my plan that everything must be risked in order to push on along the coast where our comrades had been defeated; when so near to our goal, I could not decide to give up and start the homeward journey without having convinced myself personally that progress was really impossible. On the other hand, we must not wantonly attempt something which would be disastrous for the whole expedition. Furthermore, the prospects of what one might meet northward were so dark, that I could only continue if those of my comrades, who necessarily must accompany me, volunteered to make the attempt. Once more I experienced the joy of seeing how serious they considered the task which we had set out to accomplish. Koch and Ajako immediately declared themselves willing to accompany me, and as I, provided we should have to lose yet more dogs, wished to have two men by each sledge, we strengthened our party by Bosun, who was not afraid to return to the coast where he had recently been starving.

So we decided that Dr. Wulff with Harrigan and Hendrik should make an attempt at getting their dogs down to the seals of the whirlpool. Provided we did not meet with too great difficulties, both parties might then meet in about a fortnight at Cape Salor. Failing this, Dragon Point was decided on as the place where we should all meet before the commencement of the return journey. After this we parted.

During the halt we had had high, sunny weather; but now our mortal enemy the fog once more sneaked in from the Polar Sea, raw and cold, drifting across all the land which we were to survey. We became suddenly miserable and desolate, not least because of the prospects which, according to our comrades, we must reckon on when we move eastward. It was hopeless to continue the journey whilst the visibility was so poor, and we made camp at ten o'clock in the evening between Cape Neumeyer and Cape Bennett.

It seemed well worth while taking matters easy and ruminating on the decisions which had to be made. Our position was really a very serious one. Of provisions we had merely a piece of seal meat and about a whole sealskin of blubber. Our dogs would not be able to stand an immediate period of starvation, neither could we reduce their number if they were to pull the two sledges.

As if to intensify our despondency, the barometer fell incessantly and did not promise well for the weather we might expect. Whilst the others were asleep, I sat thinking about our position.

Would it be possible to push along the path which had cost our comrades half their dogs? I was ready to give up the idea of reaching as far as Cape Morris Jesup or Cape Bridgeman, which had been my goal the whole time. But de Long Fjord? How very, very reluctantly would I relinquish that hope! It would be with a heavy heart that I, after all I had staked on this expedition, would go home without having been able to carry through my programme. The great main fjords and the north coast were now charted; and dearly we had paid for that work, because of the scarcity of game, and because of fog and deep snow. And now de Long Fjord? From our present camp to that field of work the distance is only about 100 kilometres, but if we do not get any hunting we shall probably lose all our dogs.

At five o'clock in the afternoon I make tea, and call Ajako and Bosun, who have both slept soundly, refusing to be disturbed by uncharted fjords and much too uncertain future possibilities. I consider it my duty to make the position clear to them, and to point out what significance it will have for the expedition if they succeed in procuring meat in this place.

The fog yet lies across the mountain-tops, and the barometer continues to fall, steadily and inconsiderately; but a light breeze has lifted the haze somewhat, so that the ice and the foot of the mountains are visible, and I send the two plucky bunters out.

June 17th.—At two o'clock in the morning of the 17th they return, Ajako with a giant seal, Bosun literally dressed in newly-killed game, with one goose, three hares, and eight ptarmigan.

Once more we are saved from a serious situation. Never has booty been brought to our tent which had such a decisive significance for the result of the expedition, and I am filled with happy gratitude to the fate which has so kindly favoured the two young Eskimos in this desert, where the others had to give up.

Without risking too much, we may now continue our push towards de Long Fjord, and we furthermore cache two or three meals for each team on this spot. We celebrate our good fortune with a mighty feast, in which the dogs take a generous part; then we decide to set off in the evening of the same day.

The Polar-ice, closely packed against the coast, has begun to develop casual lanes, approximately 4 kilometres from land; it was by one of these lanes that Ajako had found his seal, which, as usual, was remarkably shy.

June 18th-20th.—Cape Neumeyer is—at any rate in the weather we have had—an unusually depressing cape; it possesses occasional little valleys where a chary growth of grass enlivens the visitor; but apart from this all is stone and stone, which not even by their shape enliven the traveller. We have spent our most intense hours in this place, but other men also have crossed this point with death at their heels. It was here that Peary on his Polar expedition in the spring of 1916 tried to land when, starting from the northern extremity of Grant Land, he had been driven out of his course by a strong eastward current.

I look across the pressed-up and difficult Polar-ice where a way had to be hewn for the sledges through the ridges, whilst hungry men, living on raw and frozen bits of starved dog-flesh, toiled towards the coasts where also we had found it difficult to exist. It brings to my mind my friend Manigssoq, who on this journey had his eyes frost-bitten and was marked for life. In vain had he tried to keep up with his comrades, who in longer and longer days' journeys struggled for life as they neared Grant Land, where the ship and salvation was to be found. When at length he could manage no further, he was left in a cold snow-hut with the frozen leg of a dog for his only food, and here he fought alone against incipient frost-bite for days, until a relief party from the ship reached him and restored him to life.

With our gipsy-like temperaments, and on the strength of yesterday's catch, we were now in the happy position of being able to ignore for the present the conflicts of life which might here arise. "Forward," which was our watchword until the goal was reached, again sang through all our being. The weather was bad, showers of wet snow drifted over us, and the going was heavy and miserable. All through the day we labour ahead through the showers, which for hours rob us of any view; but as we have no time to waste, we wade stubbornly through the snow. When occasionally the thick weather eases, the most beautiful landscape is unveiled before us; in Mascart Inlet we are everywhere surrounded by high, cone-like, snowclad mountains, furrowed by many clefts which create life and change in the monotony. At the head of the inlet we see the place where the channel of the whirlpool runs out, and in this we find the solution of the problem of the open water, which in the beginning puzzled us.

Out in the middle of Mascart Inlet we meet with a depressing sight. On a high hummock of ice we find the sledge which our comrades had had to leave. Poor litter of various kinds is deposited by its side to lighten it, but the most pathetic sight is the carcase of a poor dog which had tried in vain to follow the tracks of its masters from Cape Payer, to reach exhausted this sledge where nothing eatable was to be found. Summoning its last strength, it had crawled up on the transom, where on our arrival we found it dead.

The storm seems constantly to grow worse; the squalls of wind whip our faces with wet snow; and as at last our clothing suffers too severely, we have, much against our will, to pitch our tent already by Low Point. Here we find our comrades' camp of starvation, which does not need commentaries; strewn about were the bones of the many dogs which had had to die to be eaten by their comrades and the four men who, in spite of their persistence, were unable to find sufficient food.

From the top of a small mountain we discover, rather close to land, a small seal which has crawled up onto the ice in spite of wind and weather. It is on good ice and the mere sight of it makes us imagine that we have already skinned it and put it in the pan, for none of us doubt but that, in the course of an hour or so, it will be our prey. We soon find, however, that it is an animal just as fond of its life as are the rest of us; furthermore, it is an expert in the art of teasing. As soon as we approach, long before we can get within range, it dives down through its breathing-hole; but hardly have we turned towards land before it crawls up again, repeating this comedy every time we continue the hunt.

We cannot understand the reason for the seals being so uncommonly shy here, where no hunting takes place. The fact that they are very few in number may probably sharpen their attention towards every unusual sound, more so than in other places where they gather in greater numbers; and up to this time we have merely seen one single seal at a time. Neither are there any ice-bears here to hunt them; if the bears exist at all, they are so few in numbers as to be insignificant; otherwise it is not our experience that these make the seals shy, for in Melville Bay, where the ice-bears yet have their El Dorado, the spring seals are tamer and less nervous than anywhere else in Greenland.

Joe and Hans Hendrik made the same discovery during the "Polaris" expedition, and it seemed to them so strange that the seals should disappear through their breathing-holes at the slightest creak even from a very long distance, that they communicated to Hall their supposition that human beings must exist in the neighbourhood.

From land we had watched a couple of seals attentively through our glasses before we started hunting them. When in the South of Greenland a seal crawls up on the ice to sleep, it rolls about in the snow for a quarter of an hour before it stretches out with its head on the ice, falling into a sleep so deep that, with care, one can as a rule get within range without. waking it. But up here the seal remains quiet only a few minutes at a time, then it will raise its head and look searchingly in all directions, just as if it were continually expecting an ambush of some kind or other. Thus we have come to the conclusion that it is the great and sudden pressures of ice which have made them so timid and nervous; for if a pressing-up, due to the exertion of ice masses from outside, is commenced suddenly and without warning, the little cleft where the seal lives will be closed, and its access to the ocean and to food will be barred. Even if the seal should succeed in slipping down through the fissure, it would run the risk of being killed, and this is probably the reason for the short duration of its sleep, and for its being so easily startled by the slightest sound.

When we had wasted a good deal of time on the teasing seal, we abandoned ice-hunting to try our fortune on land. Here Bosun quickly succeeded in bringing down three fat, delicious barnacle-geese, which proved a comforting compensation.

We spent a day at Low Point with quick changes in the weather, and a temperature of a constant minus 1° (Cent.). Due north the sky is clear, but thick banks of fog constantly drift in from north-west, enveloping everything in a raw, whitish-grey haze; the sun is permitted to shine on us for a few moments, then once more it disappears; towards evening a belt of fog settles on the mountains to the south-west, leaving the horizon visible, and we decide to continue.

We cross Jewell Inlet, which, with its pointed high mountains, reminds one of Mascart Inlet. We pass Cape Wykander, which proves to be an island, and from this point we enter on an even gradient of coastland trending in towards the mouth of de Long Fjord. All this even mountain-land is very fertile, and seems to be the favoured haunt of hares and ptarmigan. Without the slightest delay in our progress, we succeed in killing, almost straight from our sledges, four hares and six ptarmigan. But in spite of the wealth of willow and grass, we find no sign of musk-oxen. The whole of the connected high mountain ridge which runs from the sound by Cape Wykander in to de Long Fjord has before its foot a wide and pretty plain.

On a very low projecting point we find a small beacon which, to our surprise, contains a report from Lockwood.

In a lane 5 kilometres from land Ajako shoots a seal, and we now feel well provisioned for our stay in the fjord where we are to finish our work.

Every time we meet with memorials of those who fought the same fight for progress as we do on this lonely coast, we feel that unknown men greet us, reaching out a friendly hand to comrades who continue their trails.

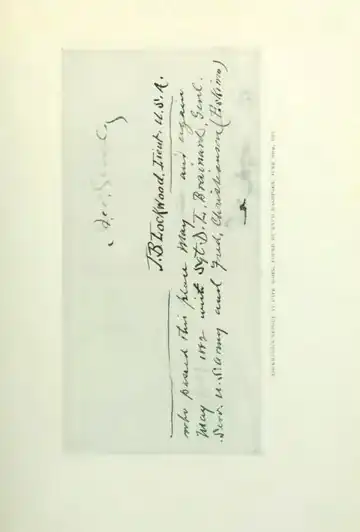

Lockwood's beacon is situated on a large plain, stretching in front of the high mountain ridge up towards Cape Mohn. It is small and insignificant, no more than 1 metre high, wherefore in no way does it attract attention. This explains how it came to pass that both Peary and McMillan drove past without noticing it. But we who examine every little irregularity in the ground, in the constant hope of finding game, discover it at a considerable distance. The report was deposited in a tin which was in no way water-tight, but, notwithstanding this, the writing was easily deciphered after the thirty-five years of varied weather which had beaten round the open beacon. With ancient Norse brevity the statement is made that in May, 1882, two Americans, Lockwood and Brainard, together with the Greenlander Frederik Kristiansen, passed this place.

Lockwood was a member of the Greely Expedition which started from America in 1881, as a section of the great International Meteorological Exploration which during that year took place all the world over. The expedition, which had its winter quarters in Lady Franklin Bay, approximately at Discovery Harbour, was taken so far north by the steamer Proteus, which immediately after the landing turned back again. Here the house was built which later on became so famous under the name of Fort Conger. In America the following arrangements had been made for the maintenance of communication with the scientists who were sent out: As early as 1882 a ship would be sent up, but if this could not get into communication with the winter quarters, a depot was to be laid down as far north in Grinnell Land as possible. The following year a new attempt would be made; if also this were to fail, a relief party was to make its way as far up into Smith Sound as possible, later on, when the ice had settled, to attempt a connection with the expedition by the aid of sledges.

In Godhavn and Upernivik the services were enlisted of two Greenlanders, Jens and Frederik Kristiansen, who, during the absence of the expedition in 1881-1884, proved to be very valuable members. The Americans—contrary to Nares' men who have previously been mentioned—employed the Eskimos fully; and with the aid of these two excellent dog-drivers they succeeded in breaking all previous records.

Lockwood was without comparison the most interesting and important man of Greely's staff. On the 3rd of April he left Fort Conger with a train of twelve men, each of whom was to pull a load of 130 pounds; further, there was Frederik, who, with his eight dogs, was to freight a load of 100 pounds per dog. On the 27th of April he returned all the human beasts of burden, and continued northward with Brainard and Frederik. Like ourselves, he got at Cape Bryant a view of the land which Beaumont at such great personal risk had explored, and he tried at once to set his course for Cape May, where all the many secrets of the land due north should have revealed themselves to the sick Englishmen. But hardly had he progressed half a score of miles inward when he met with the same soft snow which had constituted such a difficulty for Beaumont. He resolutely decided to continue northward far out at sea, rather than waste his time on details.

On the 1st of May he reached Cape Britannia, which, according to Greely's order, was the goal of his journey. But as the coast which he was to follow on the return journey was provided with many depots, and as the dogs, which had met with no difficulties worth mentioning, were as yet in prime condition, Lockwood decided at once to continue further northward, constantly keeping the distance from land necessary for good driving. This voyage must be looked upon as a reconnoitring. It was important for him to make sure of land ahead as far north as possible without examining it closely; and because of the task he had set himself he could thus with a good conscience plant his American flag on Lockwood Island in the mouth of de Long Fjord on the 13th of May. England, which for three hundred years had held the honour of being the nation which planted its flag farthest north, must now yield to the Americans. England's farthest north, reached by Markham at 83° 20' 26", was now beaten by Lockwood's 88° 24'. It was not much, but it was a record nevertheless. In his book Greely describes the event in the following manner:

"For three centuries England had held the honours of the farthest north. Now Lockwood, profiting by their labours and experiences, surpassed their efforts of three centuries by land and ocean. And with Lockwood's name should be associated that of his inseparable sledge companion Brainard, without whose efficient aid and restless energy, as Lockwood said, the work could not have been accomplished. So, with proper pride, they looked that day from the vantage-ground of the farthest north (Lockwood Island) to the desolate Cape which, until surpassed in coming ages, may well bear the grand name of Washington."

Already on the 1st of June, sixty days after they started, the expedition was back at Fort Conger, with all men in good condition.

Unfortunately, consideration of space limits my description. of Greely's Expedition, which, when one takes into consideration the tragic fate which befell it, must surely be called the most famous of them all.

The members worked energetically during the whole of their stay by Fort Conger, both in across the land and northward. The most interesting part of their work was the exploration of Grant Land, the inner reaches of which were at that time entirely unknown; by the aid of small light hand-carts the explorers were enabled to examine the land thoroughly. Especially important were the ethnographical results, as inland near Lake Hazen several Eskimo camps were found. Greely himself took part in the inland excursions, and the men's capacity for work was highly increased by the circumstance that, in contradistinction to all previous expeditions, they did not suffer from scurvy, thanks to a sensible diet.

Lockwood himself exceeded everyone else in energy and working ability. In 1883 he went northward on a fresh excursion along the land which he had discovered, and in a surprisingly short time he reached Black Horn Cliffs, where, however, he had to turn, as he found open water.

The road being blocked, Lockwood, with Brainard and Frederik, chose a new route across Grinnell Land, which was explored simultaneously with the discovery of the big Greely Fjord. In the meantime two winters had passed without communication with the relief expeditions which had been promised for the return journey; and as, unfortunately, the expedition had been ordered, failing connection with the ship, to attempt a movement southward in the direction of relief, they now began to prepare for that journey, which proved altogether disastrous and gave rise to the greatest tragedy which has ever befallen an Arctic expedition.

To this must be added that the state of affairs on board was not a happy one, things even going so far that the physician to the expedition, Dr. Pavy, was arrested for insubordination during the last summer at Fort Conger. If ever there are conditions in life where comradely co-operation under a firm leader is absolutely essential to success, they are to be found during Arctic exploration where the few people who have to live together are entirely dependent upon each other. A situation like this, therefore, proved a great calamity. Further, opinions differed as to whether a couple of sledges ought to be sent down to Littleton Island, where, as a link in the whole chain of plans put down for Greely before his departure from America, a depot had been promised. It is always easy to criticize afterwards when the results of the dispositions are evident, and it cannot be denied that the plans here mentioned, under the leadership of one of the by now well-trained sledge travellers with one of the Eskimos for his companion, must have appeared quite natural. But Greely was against the proposition and managed to frustrate it. They then decided that they should all go southward along Grinnell Land, attempting to communicate with the relief ship or depots.

When they broke up, the order was given that private property must be left behind; the officers, however, being permitted to bring a load of 16 pounds each, whereas the rankers were only allowed 8 pounds. Such partiality must have a very bad effect during an expedition, where no differentiation based on rank ought to be permitted. Furthermore, the unfortunate decision was carried that all dogs were to be left behind at Fort Conger, whereby they were cut off from all possibilities of hunting, should they have to undertake another wintering without outside help.

On the 9th of August all men left the station in boats. At this time they had yet provisions for a year, and they knew that the country was prolific with game.

Under great difficulties the boats, through drifting hummocks of ice, reached Cape Sabine, about 400 miles distant, where at last in some beacons they found information of what had hitherto been done for the relief of the expedition. The first ship was wrecked; the second, not being able to penetrate the ice sufficiently far up, had returned with all the provisions. In another beacon they were solemnly assured that everything in human power would be done to save the expedition next year.

There was nothing to do but prepare for winter as well as might be. A wretched house, consisting almost entirely of a boat with the keel turned up, was erected on Pim Island. A few depots were found, but far from sufficient for the needs of autumn, winter, and spring. One can picture to oneself the regret with which the men thought of the good warm winter-house at Fort Conger, where even a coal-mine was to be found a short distance from the door, and of all the good provisions which would have seen them through the winter; finally, there were the dogs, which could have led the hunters far inland on musk-ox hunts.

This "starvation camp," as it was later called, gives the most tragic pictures of human need and misery. Autumn passed tolerably; during that period Greely even tried to keep up the spirits of his people by lecturing to them in the midst of cold and hunger. Later on they lost strength for any attempt at resistance, and one by one they were consumed by terrible suffering. One of the Eskimos, Frederik, died as a result of over-exertion during an unsuccessful hunting excursion; the other, Jens, was drowned in his kayak during an attempt to work through thin ice in the endeavour to reach a shot seal; and as the expedition no longer had the services of these professional hunters, everything seems to have gone slowly downhill. Even the energetic Lockwood, full of initiative, succumbed to hunger, which slowly stole a march on him; towards spring, when the light returned and most of the men were unable to walk, one might discover, after the catastrophe had taken place, that one shared the sleeping-bag with a dead comrade. At long last, on the 22nd of June, 1884, the ship arrived, but then there were only six men alive out of the twenty-four.

Greely himself finishes his report with the following pathetic words:

"Towards midnight of the 22nd, I heard the sound of the steam-whistle of the Thetis, which, by the order of Captain Schley, was to call his people together. My ear did not deceive me, although I could hardly believe that, in the storm, a ship would venture so near to land.

"In a weak voice I asked Brainard and Long if they had strength enough left to go out, and to this they replied as usual that they would do their utmost. I requested them to return and inform us if they sighted a ship. In the course of ten minutes, Brainard returned from the ridge about 50 yards away, and reported in a very subdued voice that nothing was to be seen, and that Long had gone to hoist the flag of distress which had blown down. Brainard again crept into his sleeping-bag whilst we started an aimless discussion of the sound which we had heard, during which Bierderbick maintained that the ship must be lying in Payer Harbour—a statement in which I did not believe, as I thought the whistle must have come from a ship passing along the coast. We had given up all hope when suddenly we heard strange voices calling my name, and with a feeling as madly mighty as our exhausted condition permitted, it dawned on us that our country had not failed us, that all our long sufferings were passed, and the remains of Lady Franklin's Expedition saved."