Floor Games/Section III

Section III

OF THE BUILDING OF CITIES

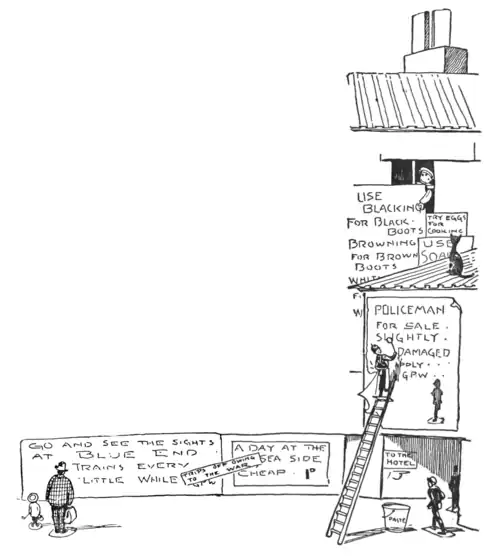

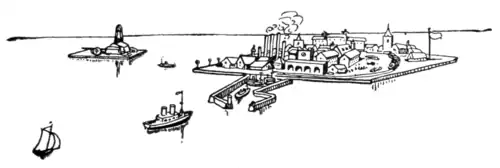

A general view of Chamois City, showing the Cherry Tree Inn and the shopping quarter

OF THE BUILDING OF CITIES

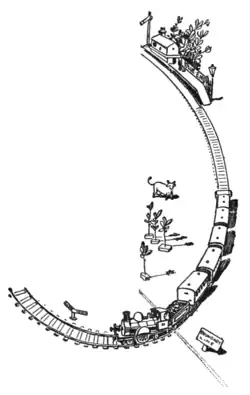

laid down and switches kept open in such a manner that anyone feeling so disposed may send a through train from their own station back to their own station again without needless negotiation or the personal invasion of anybody else's administrative area. It is an undesirable thing to have other people bulging over one's houses, standing in one's open spaces, and, in extreme cases, knocking down and even treading on one's citizens. It leads at times to explanations that are afterwards regretted.

We always have twin cities, or at the utmost stage of coalescence a city with two wards, Red End and Blue End; we mark the boundaries very care-fully, and our citizens have so much local patriotism (Mr. Chesterton will learn with pleasure) that they stray but rarely over that thin little streak of white that bounds their municipal allegiance. Sometimes we have an election for mayor; it is like a census but very abusive, and Red always wins. Only citizens with two legs and at least one arm and capable of standing up may vote, and voters may poll on horseback; boy scouts and women and children do not vote, though there is a vigorous agitation to remove these disabilities. Zulus and foreign-looking persons, such as East Indian cavalry and American Indians, are also disfranchised. So are riderless horses and camels; but the elephant has never attempted to vote on any occasion, and does not seem to desire the privilege. It influences public opinion quite sufficiently as it is by nodding its head.

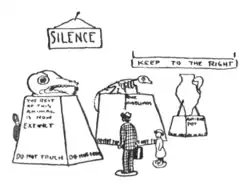

We have set out and I have photographed one of our cities to illustrate more clearly the amusement of the game. Red End is to the reader's right, and includes most of the hill on which the town stands, a shady zoological garden, the town hall, a railway tunnel through the hill, a museum (away in the extreme right-hand corner), a church, a rifle range, and a shop. Blue End has the railway station, four or five shops, several homes, a hotel, and a farm-house, close to the railway station. The boundary drawn by me as overlord (who also made the hills and tunnels and appointed the trees to grow) runs irregularly between the two shops nearest the cathedral, over the shoulder in front of the town hall, and between the farm and the rifle range.

The nature of the hills I have already explained, and this time we have had no lakes or ornamental water. These are very easily made out of a piece of glass—the glass lid of a box for example—laid upon silver paper. Such water

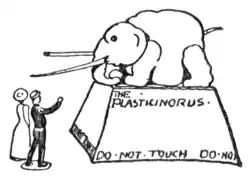

becomes very readily populated by those celluloid seals and swans and ducks that are now so common. Paper fish appear below the surface and may be peered at by the curious. But on this occasion we have nothing of the kind, nor have we made use of a green-colored tablecloth we sometimes use to drape our hills. Of course, a large part of the fun of this game lies in the witty incorporation of all sorts of extraneous objects. But the incorporation must be witty, ог you may soon convert

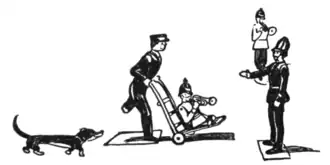

I have taken two photographs, one to the right and one to the left of this agreeable place. I may perhaps adopt a kind of guide-book style in reviewing its principal features: I begin at the railway station. I have made a rather nearer and larger photograph of the railway station, which presents a diversified and entertaining scene to the incoming visitor. Porters (out of a box of porters) career here and there with

the metallic pillar which bears the name of the station. So many toys, we find, only become serviceable with a little smashing. There is an allegory in this—as Hawthorne used to write in his diary.

("What is he doing, the great god Pan,

Down in the reeds by the river?")

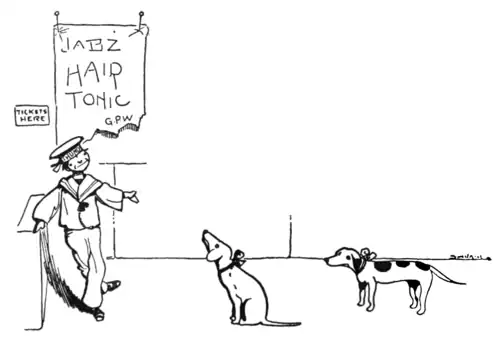

The fences at the ends of the platforms are pieces of wood belonging to the game of Matador—that splendid and very educational construction game, hailing, I believe, from Hungary. There is also, I regret to say, a blatant advertisement of Jab's "Hair Color," showing the hair. (In the photograph the hair does not come out very plainly.) This is by G. P. W., who seems marked out by destiny to be the advertisement-writer of the next generation. He spends much of his scanty leisure inventing and drawing advertisements of imaginary commodities. Oblivious to many happy, beautiful, and noble things in life, he goes about studying and imitating the literature of the billboards. He

The railway station at Blue End

"Returning from the station," as the guide-books say, and "giving one more glance" at the passengers who are waiting for the privilege of going round the circle in open cars and returning in a prostrated condition to the station again, and "observing" what admirable platforms are made by our 9 by 4½ pieces, we pass out to the left into the village street. A motor omnibus (a one-horse hospital cart in less progressive days) stands waiting for passen-

gers; and, on our way to the Cherry Tree Inn, we remark two nurses, one in charge of a child with a plasticine head. The landlord of the inn is a small grotesque figure of plaster; his sign is fastened on by a pin. No doubt the refreshment supplied here has an enviable reputation, to judge by the alacrity with which a number of riflemen move towards the door. The inn, by the by, like the station and some private houses, is roofed with stiff paper.

These stiff-paper roofs are

one of our great inventions. We get thick, stiff paper and cut it to the sizes we need. After the game is over, we put these roofs inside one another and stick them into the bookshelves. The roof one folds and puts away will live to roof another day.

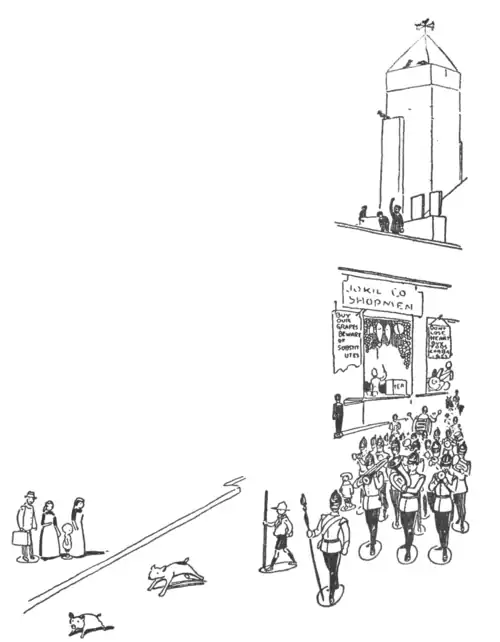

Proceeding on our way past the Cherry Tree, and resisting the cosy invitation of its portals, we come to the shopping quarter of the town. The stock in the windows is made by hand out of plasticine. We note the meat and hams of "Mr. Woddy," the cabbages and carrots of "Tod & Brothers," the general activities of the "Jokil Co." shopmen. It is de rigueur with our shop assistants that they should wear white helmets. In the street, boy scouts go to and fro, a wagon clatters by; most of the adult population is about its business, and a red-coated band plays along the roadway. Contrast this animated scene with the mysteries of sea and forest, rock and whirlpool, in our previous game. Further on is the big church or cathedral.

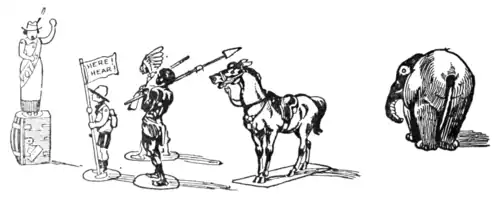

"We now," says the guidebook, "retrace our steps to the shops, and then, turning to the left, ascend under the trees up the terraced hill on which stands the Town Hall. This magnificent building is surmounted by a colossal statue of a chamois, the work of a Wengen artist; it is in two stories, with a battlemented roof, and a crypt (entrance to right of steps) used for the incarceration of offenders. It is occupied by

Note the red parrot perched on the battlements; it lives tame in the zoölogical gardens, and is of the same species as one we formerly observed in our archipelago. Note, too, the brisk cat-and-dog encounter below. Steps descend in wide flights down the hillside into Blue End. The two couchant lions on either side of the steps are in plasticine, and were executed by that versatile artist, who is also mayor of Red End,

Passing in front of the town hall, and turning to the right, we approach the zoölogical gardens. Here we pass two of our civilians: a gentleman in black, a lady, and a large boy scout, presumably their son. We enter the gardens, which are protected by a bearded janitor, and remark at once a band of three performing dogs, who are, as the guide-book would say, "discoursing sweet music." In neither ward of the city does there seem to be the slightest restraint upon the use of musical instruments.

It is no place for neurotic people.

The gardens contain the inevitable elephants, camels (which we breed, and which are therefore in considerable numbers), a sitting bear, brought from last game's caves, goats from the same region, tamed and now running loose in the gardens, dwarf elephants, wooden nondescripts, and other rare creatures. The keepers wear a uniform not unlike that of railway guards and porters. We wander through the gardens, return, descend the hill by the

The terraced hill on which stands the Town Hall. Behind can be seen the Zoölogical Gardens

You see now how we set out and the spirit in which we set out our towns. It demands but the slightest exercise of the imagination to devise a hundred additions and variations of the scheme. You can make picture-galleries—great fun for small boys who can draw; you can make factories; you can plan out flower-gardens—which appeals very strongly to intelligent little girls; your town hall may become a fortified castle; or you may put the whole

town on boards and make a Venice of it, with ships and boats upon its canals, and bridges across them. We used to have some very serviceable ships of cardboard, with flat bottoms; and then we used to have a harbor, and the ships used to sail away to distant rooms, and even into the garden, and return with the most remarkable cargoes, loads of nasturtium-stem logs, for example. We had sacks then, made of glove-fingers, and several toy cranes. I suppose we could find most of these again

if we hunted for them. Once, with this game fresh in our minds, we went to see the docks, which struck us as just our old harbor game magnified.

"I say, Daddy," said one of us in a quiet corner, wistfully, as one who speaks knowingly against the probabilities of the case, and yet with a faint, thin hope, "couldn't we play just for a little with these sacks . . . until somebody comes?"

Of course the setting-out of the city is half the game. Then you devise incidents. As I

wanted to photograph the particular set-out for the purpose of illustrating this account, I took a larger share in the arrangement than I usually do-It was necessary to get everything into the picture, to ensure a light background that would throw up some of the trees, prevent too much overlapping, and things like that. When the photographing was over, matters became more normal. I left the schoolroom, and when I returned I found that the group of riflemen which had been converging on the public-

of artillery turned up in the High Street and there was talk of fortifications. Suppose wild Indians were to turn up across the plains to the left and attack the town! Fate still has toy drawers untouched. . . .

So things will go on till putting-away night on Friday. Then we shall pick up the roofs and shove them away among the books, return the clockwork engines very carefully to their boxes, for engines are fragile things, stow the soldiers and civilians and animals in their nests of drawers, burn