Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition/Japan

W & A. K. Johnston, Edinburgh, & London.

ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA, NINTH EDITION

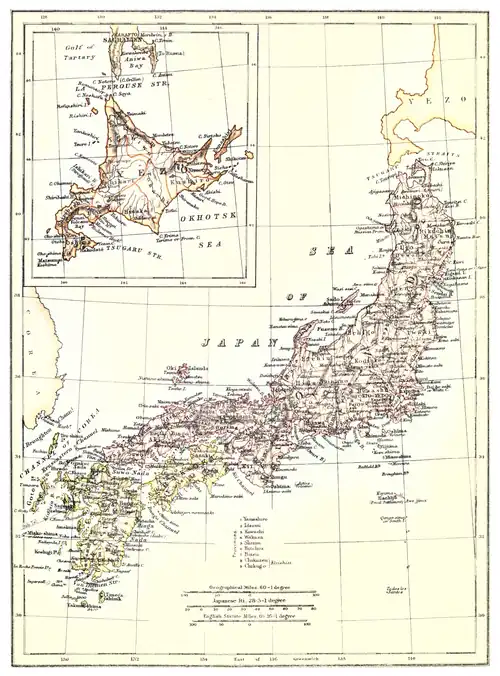

Japan

Plate IX.The empire of Japan consists of a long chain of islands separated from the eastern coast of Asia by the Seas of Japan and Okhotsk, and extending from 24° to 50° 40′ N. lat., and from 124° to 156° 38′ E. long. It commences with the Kurile Islands and descends in a southwesterly direction to the Loochoo group, to which the Japanese Government reasserted their claim in 1875. The southern portion of the island of Saghalien was ceded to Russia in exchange for the Kuriles. The whole empire is called by the natives Dai Nippon, or “Great Japan”; but Nippon or Nihon is often employed alone. Nippon means literally “sun’s origin,” i.e., the land over which the sun first rises, and thus denotes the position the empire occupies in the extreme East. The principal islands may be enumerated as follows:—

- 1. The main island, which does not bear any special name. In many of the older geographical works it is stated that Nippon is the distinctive appellation of this one island, but by the Japanese themselves the name is applied only to the whole country.

- 2. Kiushiu (lit., “the nine provinces”).

- 3. Shikoku (lit., “the four provinces”).

- 4. Yezo.

- 5. Sado.

- 6. Tsushima.

- 7. Hirado (often wrongly written Firando).

- 8. Awaji.

- 9. Ôshima (“Vries Island”) and the chain adjacent to it, terminating with Hachijô (misspelt on charts Fatsisio).

- 10. Iki, with several smaller isles.

- 11. The Oki group.

- 12. The Gotô group.

- 13. The Bonin group.

- 14. The Riukiu (Loochoo) group.

- 15. The Kurile group (Chijima; lit, “the thousand islands”).

Owing to the lack of reliable surveys, it is exceedingly difficult to form a correct estimate of the area of the Japanese empire. A few years ago the Government instituted surveying operations under the direction of skilled foreign engineers, and an ordnance map of the city of Tôkiô has already been prepared and published; but any correct calculation of the size of the whole country can hardly be obtained for some years to come. In a work on general geography published a few years ago by the Education Department at Tôkiô, the area of Japan is stated to be 24,780 square ri, which measurement, taking the linear ri as equal to 2.45 English miles, gives a total of about 148,742 miles, or nearly one-fourth more than the area of the United Kingdom. This estimate, however, is founded on maps which are far from correct.[1]

The old division of Japan into provinces was made by the emperor Seimu (131–190 A.D.), in whose time the jurisdiction of the sovereign did not extend further north than to a boundary line running from the Bay of Sendai, on the east coast of the main island, to near the present treaty port of Niigata on the west coast. The northern portion beyond this line was then occupied by barbarous tribes, of whom the Ainos (still to be found in Yezo) are probably the remaining descendants. The whole country was then divided into thirty-two provinces. In the 3d century the empress Jingô, on her return from her victorious expedition against Corea, portioned out the empire into five home provinces and seven circuits, in imitation of the Corean system. By the emperor Mommu (696–707) some of the provinces were subdivided so as to increase the whole number to sixty-six, and the boundaries then fixed by him were resurveyed in the reign of the emperor Shômu (723–756). The old division is as follows:—

I. The Go-kinai, or “five home provinces,” i.e., those lying immediately around Kiôto, the capital, viz.:—

| Yamashiro[2] | also called | Jôshiu |

| Yamato, | also called„ | Washiu. |

| Kawachi, | also called„ | Kashiu. |

| Idzumi, | also called„ | Senshiu. |

| Setsu, | also called„ | Sesshiu. |

II. The seven circuits, as follows:—

1. The Tôkaidô, or “eastern-sea circuit,” which comprises fifteen provinces, viz.:—

| Iga | or | Ishiu. |

| Isé | or„ | Seishiu. |

| Shima | or„ | Shishiu. |

| Owari | or„ | Bishiu. |

| Mikawa | or„ | Sanshiu. |

| Tôtômi | or„ | Enshiu. |

| Suruga | or„ | Sunshiu. |

| Idzu | or„ | Dzushiu. |

| Kai | or„ | Kôshiu. |

| Sagami | or„ | Sôshiu. |

| Musashi | or„ | Bushiu. |

| Awa | or„ | Bôshiu. |

| Kadzusa | or„ | Sôshiu. |

| Shimôsa | or„ | Sôshiu. |

| Hitachi | or„ | Jôshiu. |

2. The Tôzandô, or “eastern-mountain circuit,” which comprises eight provinces, viz.:—

| Ômi | or | Gôshiu. |

| Mino | or„ | Nôshiu. |

| Hida | or„ | Hishiu. |

| Shinano | or„ | Shinshiu. |

| Kôdzuké | or„ | Jôshiu. |

| Shimotsuké | or„ | Yashiu. |

| Mutsu | or„ | Ôshiu. |

| Déwa | or„ | Ushiu. |

3. The Hokurikudô, or “northern-land circuit,” which comprises seven provinces, viz.:—

| Wakasa | or | Jakushiu. |

| Echizen | or„ | Esshiu. |

| Kaga | or„ | Kashiu. |

| Noto | or„ | Nôshiu. |

| Etchiu | or„ | Esshiu. |

| Echigo | or„ | Esshiu. |

| Sado (island) | or„ | Sashiu. |

4. The Sanindô, or “mountain-back circuit,” which comprises eight provinces, viz.:—

| Tamba | or | Tanshiu. |

| Tango | or„ | Tanshiu. |

| Tajima | or„ | Tanshiu. |

| Inaba | or„ | Inshiu. |

| Hôki | or„ | Hakushiu. |

| Idzumo | or„ | Unshiu. |

| Iwami | or„ | Sékishiu. |

| Oki (group of islands). | ||

5. The Sanyôdô, or “mountain-front circuit,” which comprises eight provinces, viz.:—

| Harima | or | Banshiu. |

| Mimasaka | or„ | Sakushiu. |

| Bizen | or„ | Bishiu. |

| Bitchiu | or„ | Bishiu. |

| Bingo | or„ | Bishiu. |

| Aki | or„ | Geishiu. |

| Suwô | or„ | Bôshiu. |

| Nagato | or„ | Chôshiu. |

6. The Nankaidô, or “southern-sea circuit,” which comprises six provinces, viz.:—

| Kii | or | Kishiu. |

| Awaji (island) | or„ | Tanshiu. |

| Awa | or„ | Ashiu. |

| Sanuki | or„ | Sanshiu. |

| Iyo | or„ | Yoshiu. |

| Tosa | or„ | Toshiu. |

7. The Saikaidô, or “western-sea circuit,” which comprises nine provinces, viz.:—

| Chikuzen | or | Chikushiu. |

| Chikugo | or„ | Chikushiu. |

| Buzen | or„ | Hôshiu. |

| Bungo | or„ | Hôshiu. |

| Hizen | or„ | Hishiu. |

| Higo | or„ | Hishiu. |

| Hiuga | or„ | Nisshiu. |

| Ôsumi | or„ | Gûshiu. |

| Satsuma | or„ | Sasshiu. |

III. The two islands, viz.:—

- 1. Tsushima or Taishiu.

- 2. TsushimaIki or„ Ishiu.

Upon comparing the above list with a map of Japan it will be seen that the main island contains the Go-kinai, Tôkaidô, Tôzandô, Hokurikudô, Sanindô, Sanyôdô, and one province (Kishiu) of the Nankaidô. Omitting also the island of Awaji, the remaining provinces of the Nankaidô give the name Shikoku (“the four provinces”) to the island in which they lie; while the Saikaidô coincides exactly with the large island of Kiushiu (“the nine provinces”). This name Kiushiu must not be confounded with that of the one province of Kishiu on the main island.

In 1868, when the rebellious nobles of Ôshiu and Déwa, in the Tôzandô, had submitted to the mikado (the emperor), those two provinces were subdivided, Déwa into Uzen and Ugo, and Ôshiu into Iwaki, Iwashiro, Rikuzen, Rikuchiu and Michinoku (sometimes also called Mutsu). This increased the old number of provinces from sixty-six to seventy-one. At the same time there was created a new circuit, called the Hok’kaidô, or “northern-sea circuit,” which comprised the eleven provinces into which the large island of Yezo was then divided (viz., Oshima, Shiribéshi, Ishikari, Téshiwo, Kitami, Ifuri, Hitaka, Tokachi, Kushiro, and Nemuro) and the Kurile Islands (Chijima).

Another division of the old sixty-six provinces was made by taking as a central point the ancient barrier of Osaka on the frontier of Ômi and Yamashiro,—the region lying on the east, which consisted of thirty-three provinces, being called the Kuantô, or “east of the barrier,” the remaining thirty-three provinces on the west being styled Kuansei, or “west of the barrier.” At the present time, however, the term Kuantô is only applied to the eight provinces of Musashi, Sagami, Kôdzuké, Shimotsuké, Kadzusa, Shimôsa, Awa, and Hitachi,—all lying immediately to the east of the old barrier of Hakoné, in Sagami.

Chiu-goku, or “central provinces,” is a name in common use for the Sanindô and Sanyôdô taken together. Sai-koku, or “western provinces,” is another name for Kiushiu, which in books again is frequently called Chinsei.

Each province (kuni) is divided into what may be termed departments (kôri). The latter vary in number according to the size of the province. In the old system there were altogether six hundred and twenty-nine departments, but the addition of the Hok’kaidô has raised the number to considerably over seven hundred.

For purposes of administration the whole of the empire except the Hok’kaidô was again divided in 1872 into three cities (fu) and seventy-two prefectures (ken). The three cities are Yedo, Ôzaka, and Kiôto. In 1869 Yedo also received the name of Tôkiô, or “eastern capital,” as opposed to Saikiô (the new name for Kiôto), or “western capital.” This was in consequence of the removal of the emperor’s court from his old capital to Yedo. It may, however, be here remarked that, whilst the Japanese invariably speak of Tôkiô Fu, “the city of Tôkiô,” they use the name Kiôto Fu, “the city of Kiôto,” and not, as might have been supposed, Saikiô Fu. The limits of the prefectures (ken) were irrespective of the boundaries of the provinces. There were originally seventy-two, but a gradual process of amalgamation has considerably reduced the list; and in August 1876 a Government notification fixed the prefectures at only thirty-five, the names of which are given in the following table:—

- The Home Provinces (1½) Sakai, Hiôgo (part)—apart from the two cities of Ôzaka and Kiôto.

- Tôkaidô (8)—Ibaraki, Chiba, Saitama, Kanagawa, Yamanashi, Shidzuoka, Aichi, Miyé—apart from the city of Tôkiô.

- Tôzandô (11)—Awomori, Iwadé, Miyagi, Fukushima, Akita, Yamagata, Tochigi, Gamma, Nagano, Gifu, Shiga.

- Hokurikudô (2)—Niigata, Ishikawa.

- Sanindô (1)—Shimané.

- Sanyôdô (3½)—Hiôgo (part), Okayama, Hiroshima, Yamaguchi.

- Nankaidô (3)—Wakayama, Ehimé, Kôchi.

- Saikaidô (5)—Ôida, Fukuoka, Kumamoto, Nagasaki, Kagoshima.

From the above list it may be noted that in many instances a single ken now contains several provinces or portions of different provinces. In 1878–9 a separate prefecture (called the Okinawa ken) was created, including the Riukiu (Loochoo) group. Until that time Riukiu was governed by a king of its own, but being in fear of its powerful neighbours, China and Japan, it had for many years sent tribute to both. A question of double allegiance thus arose, which was solved by Japan asserting its sovereignty; the king received the title of noble of Japan, and the Okinawa ken was established. Whether this action on the part of the Japanese Government may not embroil them with China is a point not yet definitely settled.

Smaller islands.The total number of islands in the Japanese group, exclusive of the four main ones, is stated to be over three thousand. Many of these are mere barren rocks, uninhabited and uncultivated. Others, again, are of considerable size and exceedingly fertile, particularly the countless islets in the Suwo Nada, commonly known to Europeans under the name of the “Inland Sea,” lying between the main island on the north and the islands of Shikoku and Kiushiu on the south. The whole coast-line, too, is dotted with islands and rocks of all sizes. Ôshima, also called Vries Island, at the mouth of the Bay of Yedo, is one of considerable importance. It has many inhabitants, and its volcanic soil is fairly productive. It is the most northerly of a chain which extends as far south as the 27th degree of north latitude. The Bonin group, termed by the Japanese the Ogasawara Islands, lies far out at sea, to the south of the entrance of Yedo Bay; it consists of two large islands, separated from each other by 50 miles of sea, and a host of islets. The Japanese Government reasserted their sovereignty over the Bonins in 1878. The Kurile Islands are merely a chain of barren rocks, and the few inhabitants are chiefly occupied in the fisheries and in hunting the sea-otter. Due south from the province of Satsuma lie several minor groups, terminating with the Riukiu Islands. The Gotô group (lit. “the five islands”) extends in a westerly direction from the province of Hizen, in Kiushiu, to which it belongs.

Bays.Coast-line.—The bays along the coast are often of considerable size. The Japanese, strange to say, have no names for either their bays or their straits, the appellations found on maps and charts having been given by European navigators. Yedo Bay is perhaps the best known to foreigners, but Sendai Bay (on the east coast) and that running up to the north of the island of Awaji, and commonly called Ôzaka Bay, are also famous. Owari Bay, in the province of that name, is of considerable size. The Bay of Kagoshima, in the province of Satsuma, is long and narrow; it is well known to foreigners as having been the scene in 1863 of an attack on Kagoshima (the castle-town of the lord of Satsuma) by a British squadron. The entire coast-line teems with smaller bays and harbours, in many of which good anchorage can be found. An English man-of-war, the “Sylvia,” has for several years been employed as a surveying vessel to obtain soundings of the principal inlets and draw up charts of the coast.

Straits.The straits best known to foreigners are the Straits of Tsugaru (often miscalled Saugur in maps), which separate Yezo from the northern portion of the main island; the Straits of Akashi and of Idzumi, near the island of Awaji, at the eastern entrance of the “Inland Sea”; and the Straits of Shimonoséki, at the extreme western end of that sea, separating the main island from Kiushiu. The attack on Shimonoséki in 1864 by an allied squadron of English, French, Dutch, and American vessels, in retaliation for injuries inflicted upon foreign shipping passing through the straits by the batteries erected by the lord of Chôshiu (in which province Shimonoséki is situated) is a matter of historical note. The current in these straits is so swift that vessels have difficulty in stemming it unless under steam.

Capes.It will suffice to name a few of the almost countless promontories and capes along the coast. On the extreme north of the main island we have Riuhi-zaki and Fujishi-zaki in the Tsugaru Straits. Inuboyé no saki lies on the east coast just below the mouth of the Tonégawa. Su-saki in Awa and Miura no misaki (called by foreigners Cape Sagami) mark the entrance to the Bay of Yedo. Cape Idzu is in the province of that name, and at the southern extremity of the province of Kishiu are Idzumo-zaki and Shiwo no misaki. Muroto-zaki and Ashizuri no misaki are the chief promontories on the south coast of the island of Shikoku, both being situated in the province of Tosa. Tsutsui-zaki in Hiuga, and Sata no misaki (better known to Europeans as Cape Chichakoff) in Ôsumi are the extreme southern points of the island of Kiushiu. In the island of Yezo there are several noticeable promontories.

Harbours.The number of harbours and trading-ports called by the natives ô-minato (“large harbours”) is stated to be fifty-six, but many of these would no doubt be inaccessible to foreign vessels of heavy tonnage. They are, however, admirably adapted for the accommodation of coasting junks and fishing craft, and these vessels have no lack of places of refuge in heavy weather. In many instances the entrances are blocked by one or more small islands or rocks, which render the anchorage within even more secure. In Yezo the port of Matsumae is the one best known. The Bay of Yedo abounds with harbours, some being situated within the mouths of the rivers. In Idzu, Shimoda is one that deserves special mention; the water is there very deep, and it is a common occurrence for vessels beating up towards the entrance of Yedo Bay to seek shelter in it. Shimidzu in Suruga is also a well-known place; a long sandy promontory covered with fir trees defends the port from the sea on the south. In the province of Shima are Toba and Matoya, both magnificent harbours. The “Inland Sea” is, of course, especially rich in this respect, the harbour of Mitarai, between two islands near the province of Aki, being a favourite place of call. In Shikoku, Takamatsu in Sanuki is the best known. Kiushiu is abundantly supplied, Kagoshima in Satsuma being one of the largest and best. The harbours on the north-west coast of the main island are also numerous, and each of the islands Tsushima, Iki, and Sado possesses one. The ports thrown open to foreign trade since the year 1859 are Yokohama, Hiôgo (Kôbé), and Niigata on the main island, Nagasaki in Kiushiu, and Hakodaté in Yezo.

MountainsMountains.—Japan, as might reasonably be expected in a country where volcanoes are so numerous, is very hilly; and in some districts there are many mountains of considerable height. The most extensive plains are those of the Kuantô and Echigo, and the north of Ôshiu. The provinces of Mikawa, Mino, and Owari are also very flat. Half-way between Tôkiô (Yedo) and Kiôto lies the great watershed of the east of Japan, the table-land of Shinano, elevated some 2500 feet above the level of the sea. The ridges around or forming part of it are very lofty, particularly those of the province of Hida. The plain of Yedo lies to the east of this table-land, about 1800 feet below, while to the north the hills gradually slope away to the province of Echigo. Another range of considerable height runs due north from Aidzu to Tsugaru, thus dividing the old provinces of Ôshiu and Déwa. The province of Kai is almost entirely surrounded by mountains, and the hill scenery in Kishiu and near Kiôto is exceedingly fine. Shikoku possesses some large ridges, and the south of Kiushiu, especially in the provinces of Higo and Hiuga, is also by no means deficient. Even in the wide rice-plains throughout the country there may often be seen minor elevations or hills, rising abruptly, in some cases to a considerable height. The mountain best known to foreigners is Fuji-san,—commonly, but most erroneously, termed Fusiyama or Fusi-no-yama in geographical works. It rises more than 12,000 feet above high-water level, and is in shape like a cone; the crater is 500 feet deep. It stands on the boundary line of the three provinces of Kai, Suruga, and Sagami, and is visible at a considerable distance seaward. It is regarded by the natives as a sacred mountain, and large numbers of pilgrims make the ascent to the summit at the commencement of summer. The apex is shaped somewhat like an eight-petaled lotus flower, and offers from three to five peaks to the view from different directions; it is visible from no less than thirteen different provinces. Though now apparently extinct, it was in former times an active volcano, and Japanese histories mention several very disastrous eruptions. The last of these occurred in 1707, when the whole summit burst forth into flames, the rocks were shattered and split by the heat, and ashes fell even in Yedo (about 60 miles distant in a direct line) to a depth of several inches.[3] After Fuji-san may be mentioned Gassan in the province of Uzen, Mitaké in Shinano, the Nikkô range in Shimotsuké, Ôminé in Yamato, Hakusan in Kaga, Tatéyama in Etchiu, Kirishima-yama in Hiuga, Asosan in Higo, Tsukuba-san in Hitachi, Onsen-ga-také in Hizen, Asama-yama in Shinano, Chôkaizan in Ugo, and Iwaki in Michinoku. There are several active volcanoes in the country, that best known to foreigners being Asama-yama. This mountain is 8500 feet in height. The earliest eruption of which records now exist seems to have taken place in 1650; after that the volcano was only feebly active for one hundred and thirty-three years, when there occurred a very severe eruption in 1783. Even so lately as 1870 there was a considerable emission of volcanic matter, at which time, also, violent shocks of earthquake were felt at the treaty port of Yokohama. The crater is very deep, with irregular rocky walls of a sulphury character, from apertures in which sulphurous fumes are constantly sent forth. At present very little is known in regard to the heights of the mountains, but the subject is one that has attracted the attention of foreign residents in Japan for several years past. The following is an approximate estimate:—

| 1. |

|

12,365 feet | (above high-water mark at the town of Numadzu). | ||

| 2. |

|

8,500 feet„ | |||

| 3. |

|

7,800 feet„ | |||

| 4. |

|

5,400 feet„ | |||

| 5. |

|

5,000 feet„ | |||

| 6. |

|

4,100 feet„ | (according to Siebold). |

Rivers.Rivers.—The rivers of Japan, although very numerous, are in no case of any great length. This of course is easily explained by the fact that the islands are narrow and hilly. The longest and widest river is the Tonégawa, which rises in the province of Kôdzuké, and flows due east to the Pacific, throwing off, however, at Sékiyado in Shimôsa, a branch that flows into Yedo Bay near the capital.[4] The length of the Tonégawa is over 170 miles. At Sékiyado (which is a large and thriving river-port) the water is no less than 40 feet in depth, while a few hundred yards above that town foot-passengers can ford the stream without any great difficulty. The Shinano-gawa and Kiso-gawa, both of which take their rise in the province of Shinano, rank next to the Tonégawa. The former flows first in a north-westerly direction, next due north, and then north-east through Echigo to the sea at Niigata; the Kiso-gawa flows to the westward and then to the south, between the provinces of Mino and Owari, and finally falls into the sea at Kuwana. The Ôi-gawa rises in the south-west of Kai, and traverses the province of Tôtômi; it is less remarkable for the length of its course than for the great breadth of its bed, which near the mouth is 2½ miles across, its current being also very swift. The Fuji-kawa, flowing due south from the mountains of Kai through the province of Suruga, is famous as being one of the swiftest streams in all Japan. In the north, the Sakata-gawa flows due west from the range of mountains separating the provinces of Uzen and Rikuzen, and enters the Sea of Japan at the town of Sakata, from which it takes its name. Nearly all the rivers are fed by countless tributary streams, which in many cases form a complete network in the lower portions of the country, and thus greatly facilitate transport from the interior to the coast. On the Tonégawa and a few other streams of greater depth small river steamers ply for several miles; but in general large flat-bottomed boats, drawing as a rule but a few inches of water, are employed. It is by no means uncommon to see boats of this description in process of construction even in remote country villages on the banks of streams in which the depth of water is but from 12 to 18 inches at ordinary times. Floods are of frequent occurrence, especially at the commencement of summer, when the melting of the snows on the mountain ranges causes at times an almost incredible downflow from the higher lands to the plains. These floods invariably occasion great destruction of property, as the bridges spanning the rivers are only built of wood and turf, supported by piles. In some localities, notably in the western portion of the province of Shimôsa, traversed by the southern branch of the Tonégawa, large tracts of rice-land are almost entirely destroyed by the fine sand from the bed of the river, swept over the fields during inundations. In addition to boats, long rafts of timber are constantly to be seen descending the larger rivers; the logs are floated down in a rough state, to be afterwards thinned and sawn up at the seaport towns where the timber trade is carried on.

Lakes.Lakes.—Japan contains a large number of lakes, but only one—the Biwa Lake, in the province of Ômi—is worthy of special notice on account of its size. Its length is about 50 miles, and its greatest breadth about 20 miles. At a village called Katada, some 10 miles from its southern extremity, it suddenly contracts to a breadth of only a mile and a half, after which it again slightly expands. This lake derives its name from a fancied resemblance to the biwa or Japanese lute; the scenery around it is particularly beautiful, and it is a favourite resort for sightseers from Kiôto. An ancient Japanese legend asserts that in the year 286 B.C., in the reign of the emperor Kôrei, there occurred a terrible earthquake, when the earth opened and Lake Biwa was formed; at the same time rose the mountain called Fuji-san. In Ômi there is a small hill called Migami, which in shape slightly resembles Fuji-san, and this fact is quoted by the natives in support of the theory connecting the lake with the sacred mountain; and the inhabitants of Ômi were privileged to undertake the ascent of Fuji-san after only seven days’ purification, instead of one hundred days’, the prescribed term for all other persons. After Biwa may be noted the lakes of Chiuzenji, Suwa, and Hakoné, all of which lie far above the level of the sea. That of Chiuzenji is situated at the foot of the mountain called Nantai-zan, in the Nikkô range in the province of Shimotsuké. The scenery in its vicinity has given rise to the proverb that he who has not seen Nikkô should not pronounce the word “beautiful.” The lake of Suwa is in the province of Shinano, and can be reached by a road called the Nakasendô, running north-west from Tôkiô through the heart of the country to Kiôto. The Hakoné Lake lies in the range of hills bearing the same name just to the east of Fuji-san; the water is exceedingly cold, and of great depth. A Japanese legend, indeed, asserts that it has never been fathomed. The hill scenery around it is very picturesque, and large numbers of foreign residents from Tôkiô and the neighbouring port of Yokohama visit it during the summer months. The Inawashiro Lake, in the province of Iwashiro, is said to be about 10 miles in length. It is fed by two streams flowing from the east and north-east, while out of it flows the Aka-no-gawa, which falls into the sea near Niigata. It is surrounded by hills of no great elevation; the temperature there is cool, and in winter the streams are frozen for several weeks. On the boundary line of the provinces of Hitachi and Shimôsa there are also large tracts of water, or lagoons (Japanese numa), fed by the Tonégawa; these, though not actually lakes, may almost be classed under that heading, as their connexion with the river itself consists in many cases of but one narrow outlet. Those of chief note are the Ushiku-numa in Hitachi, and the Imba-numa, Téga-numa, and Naga-numa in Shimôsa. The country in this vicinity is as a rule exceedingly flat, but the Imba-numa is for some distance along its eastern shore bordered by small hills, thickly wooded down to the water’s edge, the whole forming a very pretty landscape. The lagoons are well stocked with fish, the large eels found in the Ushiku-numa being especially prized for excellence of flavour; in the winter months they teem with wild fowl. The inhabitants of the numerous villages along the shores are, in fact, almost entirely maintained by fishing and shooting or trapping.

Minerals.Minerals.—Japan is particularly rich in minerals, among which may be specially mentioned gold, silver, iron, copper, coal, and stone of various kinds. The gold was first discovered and melted in the year 749 A.D., during the reign of the emperor Shômu; it came from the department of Oda in the province of Ôshiu, and in the following year more was found in the province of Suruga. During the long period of Japan’s seclusion from the rest of the world, the gold discovered remained in the country, and the amount augmented year by year; and this no doubt tended in a great degree to convey to the earlier foreign visitors the impression that the supply was far more abundant than was actually the fact. The quantity of bullion exported by the Portuguese during their stay in Japan (1550–1639) may be estimated at the least at fifty-nine and a half millions sterling, or an average of £660,000 yearly. Dr Kaempfer even speaks of some years with an export of two and a half millions of gold. From 1649 to 1671 the Dutch also exported large quantities, together with silver and copper, and the total value of gold and silver alone sent out of Japan during the 16th and 17th centuries may be estimated at nearly one hundred and three millions sterling. At an exhibition held in Kiôto in 1875 were shown about twenty samples of gold ore found in different provinces. The ore is generally poor, and many gold-yielding places are now lying unworked, because the increased cost of labour renders it very difficult to work them with profit. Pure auriferous quartz has been found in the provinces of Satsuma and Kai, gravel in Ôsumi, and quartz in Rikuchiu and at the mine of Aikawa in the island of Sado. The mode in which the Japanese work the gold ores nearly resembles Western methods. They understand perfectly the separation of even the smallest quantities of gold dust from stones and gravel by means of a system of washing and levigation. They do not, however, possess any good process for the separation of gold from silver, and hence all Japanese gold contains a greater or less proportion of the latter metal. Silver ore was discovered accidentally in the year 667 A.D., in the island of Tsushima; this ore produced the first Japanese silver metal, in the year 674. From 1400 to 1600 it was obtained and melted in Japan in far larger quantities than at the present time. It generally occurs in comparatively small quantities as an admixture in several copper and lead ores. The principal mines are in the provinces of Jôshiu, Iwami, and Setsu; but it is also found mixed with lead in Hida, Iwashiro, Echizen, Echigo, Rikuchiu, Suwô, Hiuga, and Higo. Of the numerous iron ores to be found, the principal is magnetic iron ore, which forms the main basis of the Japanese iron industry. Loadstone was discovered in the year 713 in the province of Ômi. The exact date of the first manufacture of iron is unknown; it is certain only that the Japanese have worked their iron ores from the 10th century onward. The principal seats of the industry are in the provinces of Idzumo, Bingo, Ôshiu, Hiuga, Tajima, Wakasa, Bizen, Bitchiu, Shinano, Tôtômi, Kai, Suruga, and Satsuma. The best steel is manufactured in Harima, Hôki, Idzumo, and Iwami. The excellent temper of the Japanese sword-blades is well known. The most noted smiths formerly resided in the provinces of Sagami, Bizen, and Kishiu, and in the neighbourhood of Kiôto. Japanese legends assert that the first sword was forged in the reign of the emperor Sūjin (97–30 B.C.), but this statement is of course open to considerable doubt. Copper was, it is said, smelted in Japan for the first time in the year 698 at Inaba in the province of Suwô; and in the year 708 the first Japanese copper coin was cast, in the province of Musashi. Since the 10th century enormous quantities of ore have been smelted, and this metal formed the chief trade of the Dutch and Chinese at Nagasaki from 1609 to 1858,—the amount exported by the former being more than four millions of piculs and by the latter undoubtedly still more.[5] It is perhaps the metal most commonly found in Japan, and is used for all kinds of household goods, doors to storehouses, ornaments, temple-furniture, mirrors, bronzes, smoking utensils, and current coinage. It is found and smelted in all parts of the country, particularly in the northern and western provinces, and its export figures considerably in the trade returns of the treaty ports during the past few years. As a rule Japanese copper is exceedingly free from the presence of injurious metals. After the year 1600 many bronze guns were cast in Japan, the workmanship being exceedingly good; these old guns are often to be seen even now, though by far the larger number, together with the temple bells, &c., made from the same material, have been broken up and exported as old bronze by European merchants. Of other metals Japan also produces lead, quicksilver, and tin. Coal is found in large quantities, particularly in Kiushiu, where the province of Hizen contains the well-known mines of Karatsu, and in the island of Takashima, near the treaty port of Nagasaki. Coal-fields also exist in the large northern island of Yezo. Nearly all the steamers plying between Japan and China coal at Nagasaki, where this trade attracts a good deal of enterprise. The numerous quarries throughout the empire afford large quantities of stone. Marble and granite are found principally in the provinces of Shinano, Mino, and Kôdzuké; freestone is also procured from Setsu and Idzu. The huge blocks of which the ramparts of the castle at the capital are built were originally brought from the latter province. In the old castle of Ôzaka, in Setsu, there is an enormous piece of granite measuring thirteen paces in length and about 9 feet in height. The foundations of all the more ancient temples throughout the country are formed of large blocks, and these, together with the long flights of steps, still remain to prove the durability of the old style of architecture. It is strange, however, that at the present moment stone is but sparingly used for building purposes; even in the great cities the dwelling-houses are almost entirely constructed of timber, stone being used only for bridges and for edifices on a larger scale than ordinary.[6]

Climate.Climate.—The climate of Japan, as might naturally be expected in view of the great length of the chain of islands, varies to a considerable extent in different localities.[7] Thus we find that while the Riukiu and Bonin groups, lying close to the tropics, enjoy perpetual summer, the Kurile Islands in the far north of the empire share the arctic temperature of Kamtchatka. The climate is, on the whole, favourable for Europeans, although its frequent changes often prove trying to foreign residents. All the mountain ranges are wrapped deep in snow throughout the winter months; indeed, from many peaks snow never entirely disappears. In the northern provinces it has been known to fall to a depth of no less than 8 feet, and the province of Echigo is specially noted in this respect. At the treaty port of Niigata, in that province, small bamboo sheds are built out from the fronts of the dwelling-houses so as to form a covered way along which pedestrians can pass when the rest of the town is snowed up. At Tôkiô snow falls some three or four times during the winter; it covers the ground to a depth of from 3 to 5 inches on an average, but does not lie long. In January 1876, however, a remarkably severe snowstorm occurred, when the whole city was covered to a depth of 2 feet or more; so unusual was this phenomenon deemed that a large number of photographs of the landscape were taken to perpetuate the memory of the event. Farther to the south and west the cold is not, as a rule, so intense, while in the summer months the heat is far greater. Near Yokohama and Tôkiô the summer commences in May, but the heat only becomes oppressive in July and August, when the thermometer has been known to register 104° F. At the break-up of the summer there are heavy rains, which render the interior of the houses exceedingly damp and uncomfortable. After the winter there also occurs a short rainy season. The best months for making excursions into the interior are April and October, as the weather is then generally of a mean temperature. Southerly winds blow from the middle of May, and often even from April, until the end of August. On the Sea of Japan south-west winds (known as the south-west monsoon) prevail, while in Yokohama and all parts of the country adjacent to the Pacific Ocean southerly winds predominate. The south-west monsoon sets in in April and prevails until the middle or end of September; but the regularity with which the monsoons set in and blow on the Chinese coasts is unknown in Japan. On calm days land and sea breezes alternate on the Japanese coast in the same manner as elsewhere. Mention should here be made of the violent revolving storms, known as typhoons, which are closely related to the West Indian hurricanes and to the cyclones of the Indian seas. These generally occur in the months of July, August, or September; they invariably occasion great damage, not only to shipping, but also to property on land. Large trees are often snapped asunder like mere twigs, while the roofs and chimneys of foreign-built edifices suffer severely. As a rule, one of these storms is experienced every year.

Earthquakes.Destructive earthquakes have often taken place, while slight shocks are of frequent occurrence, several having been felt lately within the space of a few days. Japanese histories furnish numerous records of these phenomena. The ancient legend of the great earthquake in 286 B.C., when Mount Fuji rose and the Biwa Lake was formed, has already been noticed; but it is not possible to procure reliable information for several centuries later than the date mentioned in that fanciful tale. The earliest authentic instance is perhaps that which is said to have occurred in 416 A.D., when the imperial palace at Kiôto was thrown to the ground. Again, in 599, the buildings throughout the province of Yamato were all destroyed, and special prayers were ordered to be offered up to the deity of earthquakes. In 679 a tremendous shock caused many fissures or chasms to open in the provinces of Chikuzen and Chikugo, in Kiushiu; the largest of these fissures was over 4 miles in length and about 20 feet in width. In 829 the northern province of Déwa was visited in similar manner; the castle of Akita was overthrown, deep rifts were formed in the ground in every direction, and the Akita river was dried up. To descend to more recent instances, in 1702 the lofty walls of the outside and inside moats of the castle of Yedo were destroyed, tidal waves broke along the coast in the vicinity, and the road leading through the famous pass of Hakoné (in the hills to the east of Fuji-san) was closed up by the alteration in the surface of the earth. Of late years these disastrous earthquakes have fortunately been of more rare occurrence, and the last really severe shocks were those felt in 1854 and 1855. In the former year the provinces of Suruga, Mikawa, Tôtômi, Isé, Iga, Setsu, and Harima, and also the large island of Shikoku, were severely shaken. It was this earthquake which destroyed the town of Shimoda, in the province of Idzu, which had been opened as a foreign port in Japan, while a Russian frigate, the “Diana,” lying in the harbour at the time was so severely damaged by the waves caused by the shock that she had to be abandoned. The earthquake of 1855 was felt most severely at Yedo, though its destructive power extended for some distance to the west, along the line of the Tôkaidô. It is stated that on this occasion there were in all 14,241 dwelling-houses and 1649 fire-proof storehouses overturned in the city, and a destructive fire which raged at the same time further increased the loss of life and property.

Meteorological observations have for some time back been carefully taken at the college in Tôkiô, and efforts are now (1881) being made to start a seismological society in the capital. Japan is peculiarly a country where a learned society of this nature could gather most interesting and useful information from actual observation.

General Aspect of the Country.—The physical structure of the islands alternates between mountain ranges, rugged upland regions, wide plains, and lands consisting of an endless succession of dale and down, level fields and small ridges. Yezo has not yet become thoroughly known to foreigners; but it possesses both hills and plains, the latter being in some cases very sandy. The northern portion of the main island of Japan is exceedingly mountainous, though large moors and uncultivated steppes are to be observed on all sides. To the south-east lies the wide plain of Yedo, remarkably fertile, and closed in by lofty ranges. From this away to the west the country is hilly in the centre, with lower ground to the north and south; while in the large islands of Kiushiu and Shikoku the high ground is far in excess of the plain.

Rice.Vegetable Products.—The greater part of the cultivated land consists of rice-fields, commonly termed “paddy-fields.” These are to be seen in every valley or even dell where farming is practicable; they are divided off into plots of square, oblong, or triangular shape by small grass-grown ridges a few inches in height, and on an average a foot in breadth,—the rice being planted in the soft mud thus enclosed. Narrow pathways intersect these rice-valleys at intervals, and rivulets (generally flowing between low banks covered with clumps of bamboo) feed the ditches cut for purposes of irrigation. The fields are generally kept under water to a depth of a few inches while the crops are young, but are drained immediately before harvesting. They are then dug up, and again flooded before the second crop is planted out. The rising grounds which skirt the rice-land are tilled by the hoe, and produce Indian corn, millet, and edible roots of all kinds. The well-wooded slopes supply the peasants with timber and firewood. The rice-fields yield two crops yearly. The seed is sown in small beds, and the seedlings are planted out in the fields after attaining the height of about 4 inches. The finest rice is produced in the fertile plains watered by the Tonégawa in the province of Shimôsa, but the grain of Kaga and of the two central provinces of Setsu and Harima is also very good. Prior to the revolution of 1868–9 the fiefs of the various daimiô or territorial nobles were assessed at the estimated total yield of rice. Until very recently there existed a Government prohibition against the export of the grain. Rice not only forms the chief food of the natives, Saké.but the national beverage, called saké, is brewed from it. In colour the best saké resembles very pale sherry; the taste is rather acid. None but the very best grain is used in its manufacture, and the principal breweries are at Itami, Nada, and Hiôgo, all in the province of Setsu. Of saké there are many varieties, from the best quality down to shiro-zaké, or “white saké,” and the turbid sort, drunk only in the poorer districts, known as nigori-zaké; there is also a sweet sort, called mirin.

Forests.The whole country is clothed with most luxuriant vegetation, except in some of the very hilly regions. The principal forests consist of Cryptomeria (Japanese cedar) and pine; the ilex, maple, mulberry, and giant camellia also abound. Some of the timber is remarkably fine, and the long avenues following the line of the different high roads afford a most grateful shade in summer. On the road from Tôkiô to the celebrated temples at the foot of the Nikkô hills is an avenue nearly 50 miles in length, of cedars and pines, some of the trees being fully 50 or 60 feet in height. Unfortunately these noble specimens are fast disappearing, as the wood-cutter’s axe and saw have been ruthlessly plied during the past few years. In Japanese wood-felling a common plan is to kindle a fire at the roots of the tree; this dries up the sap in the trunk, and renders the wood harder and firmer. Two principal varieties of the pine occur, called respectively the red and the black, from the colour of the bark. The former thrives in sandy ground, while the latter grows in softer black soil. It is said that, if one of these varieties be transplanted to the soil bearing the other, it will also in time change in colour till it resembles its new companions. The tints of the maple foliage, bright green in summer and brown-red in autumn, contribute in no slight degree to the beauty of a Japanese landscape. The mulberry tree grows well in the eastern regions, where the silkworm is reared and the silk industry carried on. The bamboo is especially useful and plentiful. Bamboo clumps are seen at frequent intervals in the rice-land; they line the river banks, and flourish equally well on the higher grounds; and it would be impossible to enumerate the multifarious purposes for which the cane is used. Fruits.Of fruit-trees Japan possesses the orange, apple, walnut, chestnut, plum, persimmon, damson, peach, and vine. The fruit, however, is in most cases of quality far below that of European orchards. The best oranges come from the province of Kishiu; these have a smooth and very thin rind, and no seeds. The larger oranges, with thick and rough rind, grow throughout the country. The so-called apple resembles the large russet, but only in colour and shape; it has absolutely no flavour, and is hard and stringy. The plum, of which there are several varieties, may be said to be the best fruit obtained, next to the orange and persimmon. This latter is exceedingly plentiful and has two varieties, the soft and the hard; it is often dried, and sold packed in boxes like figs. The peaches are not remarkable either for size or flavour. The best grapes are grown in the provinces of Kai and Kawachi; both the black and the white are found, but the fruit is small, and only continues in season for a short time. The tea-plant grows well in Japan, and tea forms one of the chief exports to foreign countries. The best leaf comes from the neighbourhood of Uji, in the province of Yamashiro, to the south-east of Kiôto; but it is also largely exported from Yokohama, being produced in the fertile district in the east of the main island. The production of vegetable wax has always formed one of the principal industries of the island of Kiushiu, and the trees bearing the wax berries grow in great number on the hill slopes and round the edges of most of the cultivated fields (excepting rice-land) in the provinces of Hizen, Higo, Chikuzen, and Chikugo; in Satsuma, however, they are not so plentiful. The cotton-plant, introduced from India in 799, also thrives. The camphor tree is found in most parts of the country, particularly in some of the higher regions; on account of its agreeable smell the wood is largely used in the manufacture of small cabinets and boxes. Amongst the minor vegetable products the sweet potato is particularly plentiful; it has several varieties, that known as the Satsuma potato being perhaps the best. Water melons and gourds of various sizes and shapes thrive in the more sandy soil; and onions, carrots, small turnips, tomatoes, and beet-root are also cultivated. The brinjal bears a dark purple fruit shaped like a pear. The long white radish, called by the Japanese daikon (lit. “great root”), is exceedingly common, and forms one of the chief articles of food amongst the lower classes, who eat it either raw or dried and pickled; the average size of the root is from 18 inches to 2½ feet in length, and 1½ inches or so in diameter. Beans and peas can also be grown. The climate of Yezo is said to be very favourable for both wheat and barley, and it is probable that in future years this large island may thus prove a source of considerable gain to the Japanese. In the island of Shikoku the indigo plant is found in abundance, and it also occurs in the eastern portion of the main island. The poppy is grown in Shikoku. In ferns and creepers of various kinds Japan is particularly rich, but her list of flowers is not very lengthy. The rose, peony, azalea, camellia, lotus, and iris are, however, to be seen.[8]

Mammals.Animals.—As regards animal life Japan is well provided. The domestic animals comprise the horse, ox, dog, and cat; while the wilder tribes are represented by the bear, deer, antelope, boar, fox, monkey, and badger. In Yezo are found very large bears, so powerful as to be able to pull down a pony; in the central provinces of Shimotsuké and Shinano a small black species exists. The deer, antelope, and monkey are caught in nearly all the hilly regions throughout the whole country. Sheep do not thrive, although the hardier goat does,—the reason assigned for this being that the “bamboo grass,” with its sharp-edged and serrated blade, proves very deleterious as pasture. In the western part of the province of Shimôsa a sheep-farm was started a few years ago; but it is not yet possible to judge whether the venture will prove successful in any great degree. In the meantime sheep are usually imported from China. The Japanese horses, or rather ponies, are not very powerful animals; they stand on an average from 13 hands 2 inches to 14 hands 2 inches in height. They are thick-necked and rather high-shouldered, but fall off in the hind quarters. Large numbers of ponies are imported from China. At the Shimôsa farm experiments have been made in putting an Arab or Barb to a Japanese mare; the half-bred animal thus obtained compares very favourably with the pure native breed, being of better shape and of far superior speed. The oxen are small but sturdy, and it is probable that, if the vast tracts of moorland at present lying uncultivated in the northern provinces were utilized for breeding cattle, substantial gains would be secured. The ordinary Japanese dog is very like the Eskimo dog, and is generally white, grey, or black in colour. A few, however, are red-brown, and much resemble the fox; these are used by the hunters in the pursuit of game. There are several species of monkeys, and large numbers of these animals, taken in the hills of Kai and Shinano, are brought into the Tôkiô market, where they are sold for food; the flesh is white and very palatable. Wild birds[9] are represented in Birds.Japan by the cormorant, the crane (Grus leucauchen, Jap. Tan-chiyan, is the national crane), wild goose (at least eight species), swan (Cygnus musicus), mallard, widgeon, teal (four species, including falcated teal or Yoshi-gamo), pheasant, woodcock, wood-pigeon, plover, and snipe. There are also found the bittern, the heron, and the white wader, commonly known as the “paddy-bird.” Prior to 1868 there existed very stringent laws prohibiting the ordinary Japanese from shooting or snaring the crane, goose, or swan. One species of bittern was even deemed worthy of a special rank of nobility, and is to this day known as the go-i sayi, or “bittern of the fifth grade,”—a quaint conceit, reminding us of the well-known jest of Henry VIII. in knighting the loin of beef. Many varieties of domestic fowls exist, the tiny bantam being one of the most celebrated; there is also a large game-cock said to have been originally imported from Siam. Flocks of tame pigeons are to be seen in nearly every farm-yard. The lark, swallow, and common sparrow are as numerous as in England. One of the most beautiful birds is the drake of the species generally called the “mandarin-duck” (Aix galericulata, Jap. Oshi-dori), found on small streams in country districts. When in full plumage this drake presents an exquisite combination of bright colours, and two broad feathers, of a deep golden tint and shaped like a fan, stand erect above the back from under the wings. Fishes.The Japanese fisheries are marvellously productive, and afford occupation to the inhabitants of the countless villages along the coasts. Herrings are caught off the island of Yezo, and the bonito, cod, sole, crab, and lobster are found in great plenty on nearly every part of the coast. In some of the rivers in Yezo, and also in the Tonégawa, fair-sized salmon are caught; and there is also a fish very much resembling the trout. The tai, a large fish of the carp species, is esteemed a special delicacy: of this there are two varieties,—the red tai, caught in rivers with sandy beds, and the black tai, found at the mouths of streams where the darker soil of the sea bed commences. Eels, small carp, and fish of many other kinds are freely taken in nearly all the minor lakes and streams. The oyster is found in considerable quantities in the shallows at the head of the Bay of Yedo and elsewhere. To any student of zoology a visit to Japan would prove in the highest degree interesting.[10]

Communication.—The means of transport, although not exceptionally good, have yet improved considerably during the past few years. Railway.There are but two lines of railway in Japan, both very short. The first (opened to traffic in 1872) runs from Tôkiô to Yokohama, and is but 18 miles in length. Shortly afterwards a line of about the same length was completed between the port of Hiôgo end the city of Ôzaka, and this line was in 1877 extended from the latter place to the city of Kiôto, the opening ceremony taking place on the 5th of February in that year. Both these lines were opened by the emperor in person. Surveying operations have been going on for some years, with a view to the construction of other railways, and in some districts the direction of future lines has already been staked out. Mention has been already made of the great facilities for transport afforded by the network of small streams throughout the country. Roads.The system of roads, too, is very fair, although in remote districts the work of supervision and repair is not done so carefully as is really necessary. Of the highways the Tôkaidô is that best known to foreigners. This is nearly 307 miles in length, and connects Kiôto and Tôkiô. Its course lies along the south-eastern coast of the main island, and it is the only road in the country which is named after the circuit that it traverses. Dr Kaempfer, one of the early residents in the Dutch factory at Nagasaki, gives in his well-known History of Japan a graphic and entertaining account of his journey from Nagasaki to Yedo in 1691, part of which he made by the Tôkaidô. One of the most remarkable works recently completed by Japanese labour, without aid from foreign engineers, is a tunnel on this road. It is situated about 6 miles to the westward of the large town of Shidzuoka, and about 106 miles west of Tôkiô. The tunnel is cut through a high ridge of hills intersecting the Tôkaidô. The old line of road passed over the summit of the ridge, but this engineering work renders the journey far shorter and easier. A good roadway, some 18 feet in breadth, leads up the ridge on either side, in a zigzag direction, so as to admit of wheeled vehicles passing along it with perfect safety; and the tunnel runs through the centre of the hill, thus connecting the two roadways. The passage is about 200 yards in length; at the eastern end it is faced with stone, then the roof is supported by timber arches for some distance; a small portion is next hewn out of a stratum of solid rock; and finally the timber arches are again continued as far as the western extremity. The breadth throughout is about 12 feet, and the height about 10 feet. As the tunnel runs in a curved line, owing to the formation of the hill, and is thus very dark, lamps are placed in it at intervals; while at each end are fixed in the ground several posts, each surmounted by a brightly polished oblong plate of tin, to reflect the rays of the sun into the interior. This important work was commenced in 1873, but was not completed until March 1876. Another road between Kiôto and Tôkiô is the Nakasendô, also called the Kiso-kaidô; this runs through the heart of the country, to the north of the Tôkaidô, and is a little over 323 miles in length. Some of the hill scenery on the western half of this road is exceptionally grand; the elevation in many parts is so great that in winter the roadway is much obstructed by snow. The longest high road in Japan is the Ôshiu-kaidô, running northward from Tôkiô to Awomori on the Tsugaru Straits. It traverses the provinces of Musashi, Shimotsuké, Iwashiro, Rikuzen, Rikuchiu, and Michinoku, and its length is given at nearly 444 miles. Two roads from Tôkiô to Niigata exist, the longer being about 264 and the shorter about 225 miles in length; the latter is said to be impassable in winter. Neither of these possesses a name, and for a considerable distance each is identical with the Nakasendô. Another road, which, though far shorter than those already mentioned, still possesses great interest for the traveller on account of the beauty of its mountain scenery, is the Kôshiu-kaidô. It unites Tôkiô and Kôfu, the chief town in the province of Kai, and is 77 miles in length; from Kôfu a continuation of it joins the Nakasendô at Shimo-no-suwa, in the province of Shinano, some 32 miles further. To the west of Kiôto lie many other roads, but they are of less importance because there is little traffic in the Sanindô, while that of the Sanyôdô is conducted in junks which ply on the Inland Sea. In the islands of Shikoku and Kiushiu the roads are stated to be very bad, particularly in the mountainous regions lying in the southern portion of the latter, on the confines of the provinces of Hiuga, Higo, and Satsuma.

The question of road superintendence is one of which the Japanese Government has fully realized the importance. At a general assembly of the local prefects held at Tôkiô in June 1875 there was brought forward a bill to classify the different roads throughout the empire, and to determine the several sources from which the sums necessary for their due maintenance and repair should be drawn. After several days discussion all roads were eventually ranged under one or other of the following heads:—

- I. National roads, consisting of—

- Class 1. Roads leading from Tôkiô to the various treaty ports.

- Class 2. Roads leading from Tôkiô to the ancestral shrines of Japan in the province of Isé, and also to the various fu (“cities”), or to the military stations.

- Class 3. Roads leading from Tôkiô to the various ken (“prefecture”) offices, and those forming the lines of connexion between the various fu and military stations.

- II. Ken (“prefecture”) roads consisting of—

- Class 1. Roads connecting different prefectures, or leading from the various military stations to their several outposts.

- Class 2. Roads connecting the head offices of the various cities and prefectures with their several branch offices.

- Class 3. Roads connecting noted localities with the chief town of such neighbourhoods, or leading to the seaports convenient of access from those localities.

- III. Village roads, consisting of—

- Class 1. Roads passing through several localities in succession, or merely leading from one locality to another.

- Class 2. Roads specially constructed, for benefit of irrigation, pasturage, mines, manufactories, &c., consequent upon measures determined by the local population.

- Class 3. Roads constructed for the benefit of Shintô shrines, Buddhist temples, or for cultivation of rice-fields and arable land.

Of the above three headings, it was decided that all national roads should be maintained at the national expense, the regulations for their repair, cleansing, &c., being entrusted to the care of the prefectures along the line of route, but the cost incurred being paid from the imperial treasury. Ken roads are to be kept up by a joint contribution from the Government and from the particular prefecture, each paying one-half of the sum needed. Village roads, being for the convenience of the local districts alone, are to be maintained at the expense of such districts under the general supervision of the corresponding prefecture. The width of the national roads was determined at 7 ken[11] for class 1, 6 ken for class 2, and 5 ken for class 3; the prefecture roads were to be from 4 to 5 ken; and the village roads were optional, according to the necessity of the case.

Vehicles.On most of the high roads run small stage waggons of various sizes, but these are as a rule badly made, insecure, and for the conveyance of passengers alone. In the mountainous regions, and especially in the hills immediately behind the foreign settlement (Kôbé) at Hiôgo, in the province of Setsu, small bullock cars are to be seen. These are roughly made of untrimmed timber, and are anything but strong; each rests on three wheels of solid wood, and is drawn by one bullock. They are, however, very useful for the conveyance of blocks of stone from the hills, and for rough country work. In the large towns, and also on all fairly level roads, passengers may travel in small two-wheeled carriages called jin-riki-sha; these are in shape like a miniature gig, and are as a rule drawn by a single coolie, though for rapid travelling two men are usually employed. In the city of Tôkiô alone there exist over 10,000 of these jin-riki-sha, and various improvements as regards their style, shape, and build have been introduced since 1870, the year in which they first came into use. Many are of sufficient size to carry two persons, and on a good road they travel at the rate of about 6 miles an hour; the rate of hire is about 5d. per Japanese ri, or about 2d. per mile. For the transport of baggage or heavy goods large two-wheeled carts are in use; these are pushed along by four or six coolies. Until very lately the only vehicle employed in travelling was the palanquin. Of these there were two kinds, viz., the norimono, a large litter carried by several bearers, and principally used by persons of the better class, and the kago, still to be seen in hilly districts where carriages cannot pass. The kago is a mere basket-work conveyance, slung from a pole carried across the shoulders of two coolies; and it is easy to see that the substitution of the wheeled jin-riki-sha drawn by only one man was a great improvement as regards both economy of labour and facility of locomotion. In country districts, and wherever the roads are stony or narrow, long strings of pack-horses meet the eye. These animals are shod with straw sandals to protect the frog of the hoof, and their burden is attached by ropes to a rough pack-saddle without girths. They go in single file, and move only at a walk. To their necks is attached a string of small metal bells,—a survival of the ancient usage whereby a state courier was provided with bells to give timely warning of his approach at the different barriers along his route, and so to guard against any impediment or delay. The peasants also often employ oxen as beasts of burden in hilly regions; these animals, too, are shod with straw sandals, having a portion raised so as to fit into the cleft in the hoof. Burdens of moderate weight are usually carried by coolies, one package being fastened at each end of a pole borne across the shoulder. In remote districts even the Government mails are thus forwarded by runners. In all the post-towns and in most of the larger villages are established transport offices, generally branches of some head office in the capital, at which travellers can engage jin-riki-sha, kago, pack-horses, and coolies, or make arrangements for forwarding baggage, &c. The tariff of hire is fixed by the Government, and this is paid in advance, a stamped receipt being given in return. Travelling guilds.Most of the inns in the post-towns subscribe to one or another of the so-called travelling guilds, each of which has a head office in Tôkiô, and often in Kiôto and Ôzaka. Upon application at this office, the traveller can obtain a small book furnishing general information as to the route by which he proposes to proceed,—such as the distances between the halting places, the names of rivers and ferries, and hints as to places of interest along his road. It also contains a full list of the inns, &c., enrolled on the books of that guild, a distinction being made between lodging-houses and places where meals alone are provided. To this list each landlord is obliged, at the traveller’s request, to affix his stamp or seal at the time of presenting his account; and by this system cases of incivility or overcharge can be reported at the head office, or application made there in the event of articles being forgotten and left behind at any inn. The Japanese themselves seldom travel in the interior except under this system, and were foreign visitors only to follow their example they might avoid a good deal of the inconvenience they not unfrequently experience.

Cities.Towns.—The towns and villages are very numerous along the line of the great roads. The three great cities are Tôkiô (Yedo), Ôzaka, and Kiôto. The last-named was the ancient capital, and had been in existence for centuries before Tôkiô, and also for a very considerable time before Ôzaka was built. Now, however, these two have rapidly outstripped Kiôto both in size and importance, and are in fact the two great centres of trade throughout the whole country. The emperor’s court now resides at Tôkiô, and it is there that the foreign legations are stationed. The city of Ôzaka (often wrongly spelt Osacca) is purely mercantile; it is intersected by numberless canals spanned by bridges that are in some cases of great length, and a very large proportion of the buildings are storehouses for merchandise. The Japanese mint (opened in April 1871) is at Ôzaka. Treaty ports.Next in importance to these three cities may fairly be classed the various ports thrown open, under the treaties with Western powers, to foreign trade. Commencing from the north, we come first to Hakodaté (erroneously spelt Hakodadi) in the south of the island of Yezo. There is here no distinct foreign settlement, the houses of the few Europeans being mingled with those of the natives. The chief exports are dried fish and seaweed. On the main island the most northern port is Niigata, in the province of Echigo, where also no foreign settlement as yet exists. The trade is exceedingly small, owing to the bad anchorage. A bar of sand at the mouth of the river (the Shinano-gawa) prevents the approach of foreign-built vessels, and the roads off the river mouth are so unprotected that when a heavy gale blows the European ships often run across to the island of Sado for shelter. Some little trade, however, is carried on, the neighbourhood being very fertile; rice and copper are the chief productions. Yokohama, about 18 miles to the south of the capital, and situated on the western shore of the Bay of Yedo, enjoys by far the greater proportion of the whole foreign trade of Japan. The foreign settlement is very large, and numerous bungalows and small villas of the European residents are also built on a hill (known as the “Bluff”) overlooking the “settlement” proper. The chief exports are tea and silk; the former goes principally to the United States and to England, and the latter to the French markets. Large business transactions also take place in silkworm eggs and cocoons, as well as in copper, camphor, and sundry other articles of trade. Proceeding westward, we come to the port of Hiôgo, in the province of Setsu. The foreign settlement, generally called Kôbé, is not so large as that of Yokohama, but the streets are wider and more commodious. A railway connects this place with Ôzaka, where there is also a foreign settlement, though of very small size. The principal exports here are tea, silk, camphor, vegetable wax, &c. Nagasaki, the best known by name of all the open ports, is in the province of Hizen, in the large south western island of Kiushiu. The foreign settlement is small, though the native town is of considerable extent. Coal is the staple export. Dr Kaempfer’s History of Japan gives a most exhaustive and interesting description of the everyday life of the early Dutch residents at this port, where they were pent up in the tiny peninsula of Deshima (commonly misspelt Decima or Dezima) in the harbour. Castle towns.Throughout the rest of the country the largest towns are as a rule those that were formerly the seats of the territorial nobles (daimiô), and are even now commonly known as “castle-towns.” It is easy to conceive that in the olden days, under the feudal system, the residence of the lord of the district formed a kind of small metropolis for that particular locality; and the importance thus attaching to the castle-towns has in most cases survived the departure of the nobles to the capital. The castles usually stood some slight distance from the rest of the town, often on a hill or rising ground overlooking it. In the centre rose the keep or citadel, a strong tower of three or five stories, commanding the whole of the fortifications; this was surrounded by high earthen ramparts, faced on the outside with rough-hewn blocks of stone and defended by a moat, which was often of considerable width. The gateways were square, with an outer and an inner entrance, constructed of stone and heavy timbers. The lines of fortification were as a rule three in number. Above the ramparts rose a slight superstructure of wattled stakes, whitewashed on the outside and loopholed for musketry and archers’ shafts. The whole produced a very striking effect when viewed from some slight distance, the grey stone and the brighter whitewash showing distinctly from among the dark foliage of the trees in the pleasure grounds within the enclosure. It was not, however, every castle that was built on the scale just described; many of them were exceedingly small, and were defended only by narrow ditches and weak wooden gates, the buildings within being thatched with straw and hardly superior to the ordinary peasant’s dwelling. Most of these castles have been demolished, but a few yet remain nearly intact to tell the tale of the former pomp and state of the feudal nobility. On the outskirts of the castle dwelt the retainers of the daimiô, Houses.their houses being sometimes situated within the outermost moat, and sometimes, again, completely beyond it. The houses of the townspeople still stand in their original positions. They are constructed almost entirely of wooden posts, beams, and planks, the roofs being generally tiled. The floors are raised to a height of about 18 inches from the level of the ground, and are covered with large straw mats an inch and a half in thickness. These mats are nearly all 6 feet in length by 3 in breadth, are covered with a layer of finely plaited straw, and have the edges bound with some dark cloth. The doors to the rooms are formed of sliding screens of wooden framework covered with paper; these are 6 feet high, and move in grooves in the beams fixed above and below them. In the houses of well-to-do persons, these slides are often covered with coarse silken stuff, or formed of finely planed boards, usually decorated with paintings. At one side of the room is generally seen a recess, with a low dais; on this various ornaments or curiosities are ranged, and a painted scroll is hung at the back of the whole. A few years back, before the wearing of swords was prohibited, a large sword-rack (often of finely lacquered wood) usually occupied the place of honour on the dais. The ceilings are of thin boards, with slender cross-beams laid over them at intervals. Except in the larger towns, there are hardly any buildings of more than two stories, though the inns and lodging-houses sometimes have as many as four. The front of the dwelling is either left entirely open, or, with the better class of tradespeople, is closed by a kind of wooden grille with slender bars. Those who can afford it usually shut in the frontage altogether by a fence, through which a low gateway opens upon a small garden immediately in front of the entrance to the dwelling. At the back there is generally another tiny garden. All round the house runs a narrow wooden verandah, of the same height as the floor, over which the roof protrudes; this verandah is completely closed at night or in stormy weather by wooden slides known as “rain-doors,” moving in grooves like the slides dividing the rooms in the interior. Next in importance to the castle-towns come the Post-towns.post-towns along the high roads, where travellers can obtain accommodation for the night, or engage conveyances and coolies for the road. The houses are similar to those already described, but are built on a smaller scale, and most of them are thatched instead of being tiled. The inns and tea-houses are the grand feature of these towns; as a rule the accommodation there to be obtained is excellent, though this is of course only on the great highways. In remote country districts the traveller is frequently forced to rough it, and put up with what he can find in the way of shelter. Each post-town possesses an office for the receipt, forwarding, and delivery of the postal mails; as a rule the mayor or vice-mayor of the district is charged with this duty.

Villages.Rural Life.—The agricultural villages are often very poor places, the houses being dilapidated, and the food and clothing of the peasants meagre in the extreme. In many instances the farm-buildings are situated in the midst of the rice-fields or on a hill slope, at some little distance from the road. Even the women and children go out to till the ground from early morn until late in the evening, their labour being sometimes varied by felling trees or cutting brushwood on the hills. In some localities they eke out their means of livelihood by snaring birds, or by fishing in the numerous ponds and rivulets. Those who can afford to do so keep a pack-horse or an ox to be used either as a beast of burden or to draw the plough. Farming operations.The farming implements are in many cases very primitive. The plough is exceedingly small, with but one handle, and is easily pulled through the soft mud of the rice-fields by a single pony or a couple of coolies. To separate the ears of grain from the stalks the latter are pulled by hand through a row of long iron teeth projecting from a small log of timber; the winnowing fans are two in number, one being worked by each hand at the same time. The spades and hoes used are tolerably good implements, but the sickle consists merely of a straight iron blade, some 4 inches in length, pointed, and sharpened on one side, which projects from a short wooden handle about 15 inches long. When the grain is gathered in, the straw is stacked in small sheaves and left in the fields to dry, after which it is used for thatching or as litter for cattle. In the wilder districts the peasantry are wretchedly poor, and cannot indeed afford to eat even of the rice they cultivate; their ordinary food is millet, sometimes mixed with a little coarse barley. The potato and the long radish (daikon) are almost the only other articles of food within their means. Agrarian riots are not unfrequently occasioned by bad harvests or scarcity from other causes, and the consequences are sometimes very disastrous, the peasants, when once excited, being prone to burn or pillage the residences of the local officials or headmen of the villages. These riots do not, however, arise as in former days from the exactions of the lords of the soil. There is no doubt that prior to the revolution of 1868–69 the peasantry were in too many cases grievously oppressed by their feudal chiefs, especially on those estates owned by the hatamoto or petty nobility of the shôgun’s court at Yedo. These nobles, with some very rare exceptions, resided continuously in the city, leaving their fiefs under the control and management of stewards or other officers; whenever money was needed to replenish the coffers of the lord, fresh taxes were laid on the peasantry, and, should the first levies prove insufficient, new and merciless exactions were made. Under the present central Government, however, the condition of the Japanese agricultural classes has been greatly ameliorated. A fixed land-tax is levied, so that the exact amount of dues payable is known beforehand. In the event of inundations, poor harvests, or similar calamities, Government grants are constantly made to the sufferers.

Education.Education.—Throughout the whole country schools have been established, for the support of which the Government often gives substantial assistance. The cost of tuition in these establishments is generally fixed at a rate within the means of the poorest classes. In most of the remote villages the schoolhouse is now the most imposing building.

Administration.Administration.—Court-houses have been erected in each prefecture, where the laws are administered by Government officials appointed by the department of justice at the capital. These courts are placed under a smaller number of superior courts, to which appeals lie, and these are in turn subordinate to a supreme court of appeal in Tôkiô. Law-courts.By a Government edict issued on the 13th of September 1876 the titles and jurisdiction of the various courts were fixed as follows:

| 1. |

|

Tôkiô fu, Chiba ken. | ||

| 2. |

|

Kiôto fu, Shiga ken. | ||

| 3. |

|

Ôzaka fu, Sakai ken, and Wakayama ken. | ||

| 4. |

|

Kanagawa ken. | ||

| 5. |

|

Hok’kaidô. | ||

| 6. |

|

Hiôgo ken, Okayama ken. | ||

| 7. |

|

Niigata ken. | ||

| 8. |

|

Nagasaki ken, Fukuoka ken. | ||

| 9. |

|

Tochigi ken, Ibaraki ken. | ||

| 10. |

|

Gumma ken, Saitama ken. | ||

| 11. |

|

Awomori ken, Akita ken. | ||

| 12. |

|

Iwadé ken, Miyagi ken. | ||

| 13. |

|

Yamagata ken, Fukushima ken. | ||

| 14. |

|

Shidzuoka ken, Yamanashi ken. | ||

| 15. |

|

Nagano ken, Gifu ken. | ||

| 16. |

|

Ishikawa ken. | ||

| 17. |

|

Aichi ken, Miyé ken. | ||

| 18. |

|

Shimané ken. | ||

| 19. |

|

Ehimé ken. | ||

| 20. |

|

Kôchi ken. | ||

| 21. |

|

Yamaguchi ken, Hiroshima ken. | ||

| 22. |

|

Kumamoto ken, Ôida ken. | ||

| 23. |

|

Kagoshima ken. |

Four superior courts, having jurisdiction over the above, were then also established, viz.:—

|

Tôkiô, Yokohama, Tochigi, Urawa, Aichi, Shidzuoka, Niigata, and Matsumoto courts. | ||

|

Kiôto, Ôzaka, Kôbé, Kanazawa, Matsuyama, Kôchi, Matsuyé, and Iwakuni courts. | ||

|

Awomori, Ichinoséki, Yonézawa, and Hakodaté courts. | ||

|

Nagasaki, Kumamoto, and Kagoshima courts. |

Police.Small police stations have been erected in all towns and villages of any importance; along the high roads the system is carefully organized and well carried out, though in distant localities the police force is often wholly inadequate to the numbers of the population. The Japanese lower orders are, however, essentially a quiet and peaceable people, and thus are easily superintended even by a very small body of police. In the capital and the large garrison towns it is a different matter, and collisions frequently occur with the riotous soldiery. The military stations are established in some of the larger castles throughout the country, the principal garrisons being at Tôkiô, Sakura in Shimôsa, Takasaki in Kôdzuké, Nagoya in Owari, Ôzaka in Setsu, Hiroshima in Aki, and Kumamoto in Higo.