Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition/Acoustics

ACOUSTICS

1.Acoustics (from ἀκούω, to hear) is that branch of Natural Philosophy which treats of the nature of sound, and the laws of its production and propagation, in so far as these depend on physical principles. The description of the mechanism of the organ of voice and of the ear, and the difficult questions connected with the processes by which, when sound reaches the drum of the ear, it is transmitted to the brain, must be dealt with in separate articles of this work. It is to the physical part of the science of acoustics that the present article is restricted.

Part I.

General notions as to Vibrations, Waves, &c.

2.We may easily satisfy ourselves that, in every instance in which the sensation of sound is excited, the body, whence the sound proceeds, must have been thrown, by a blow or other means, into a state of agitation or tremor, implying the existence of a vibratory motion, or motion to and fro, of the particles of which it consists.

Thus, if a common glass-jar be struck so as to yield an audible sound, the existence of a motion of this kind may be felt by the finger lightly applied to the edge of the glass; and, on increasing the pressure so as to destroy this motion, the sound forthwith ceases. Small pieces of cork put in the jar will be found to dance about during the continuance of the sound; water or spirits of wine poured into the glass will, under the same circumstances, exhibit a ruffled surface. The experiment is usually performed, in a more striking manner, with a bell-jar and a number of small light wooden balls suspended by silk strings to a fixed frame above the jar, so as to be just in contact with the widest part of the glass. On drawing a violin bow across the edge, the pendulums are thrown off to a considerable distance, and falling back are again repelled, &c.

It is also in many cases possible to follow with the eye the motions of the particles of the sounding body, as, for instance, in the case of a violin string or any string fixed at both ends, when the string will appear, by a law of optics, to occupy at once all the positions which it successively assumes during its vibratory motion.

3.It is, moreover, essential, in order that the ear may be affected by a sounding body, that there be interposed between it and the ear one or more intermediate bodies (media), themselves capable of molecular vibration, which shall receive such motion from the source of sound, and transmit it to the external parts of the ear, and especially to the membrana tympani or drum of the ear. This statement is confirmed by the well-known effect of stopping the ear with soft cotton, or other substance possessing little elasticity.

The air around us forms the most important medium of communication of sound to our organs of hearing; in fact, were air devoid of this property, we should practically be without the sense of hearing. In illustration of the part thus assigned to the atmosphere in acoustics, an apparatus has been constructed, consisting of a glass receiver, in which is a bell and a hammer connected with clock-work, by which it can be made to strike the bell when required. The receiver is closed air-tight by a metal plate, through which passes, also air-tight, into the interior, a brass rod. By properly moving this rod with the hand, a detent is released, which checks the motion of the wheel-work, and the hammer strikes the bell continuously, till the detent is pushed into its original position. As long as the air in the receiver is of the usual atmospheric density, the sound is perfectly audible. But on rarefying the air by means of an air-pump (the clock-work apparatus having been separated from the plate of the pump by means of a pad ding of soft cotton), the sound grows gradually fainter, and at last becomes inaudible when the rarefaction of the air has reached a very low point. If, however, at this stage of the experiment, the metal rod be brought into contact with the bell, the sound will again be heard clearly, because now there is the necessary communication with the ear. On readmitting the air, the sound recovers its original intensity. This experiment was first performed by Hawksbee in 1705.

4.Inasmuch, then, as sound necessarily implies the Laws of existence in the sounding body, in the air, &c., and (we may add) in the ear itself, of vibratory motion of the particles of the various media concerned in the phenomenon, a general reference to the laws of such motion is essential to a right understanding of the principles of acoustics.

The most familiar instance of this kind of motion is afforded by the pendulum, a small heavy ball, for instance, attached to a fine string, which is fixed at its other end. There is but one position in which the ball will remain at rest, viz., when the string is vertical, there being then equilibrium between the two forces acting on the body, the tension of the string and the earth's attractive force or gravity. Thus, in the adjoining fig., if is the point of suspension, and the vertical through that point of length , equal to the string, is the equilibrium position of the particle.

Fig. 1.

Let now the ball be removed from to , the string being kept tight, so that describes the arc of a circle of radius equal to , and let the ball be there dropped. The tension of the string not being now directly opposite in direction to gravity (), motion will ensue, and the body will retrace the arc . In doing so, it will continually increase its velocity until it reaches the point , where its velocity will be a maximum, and will consequently pass to the other side of towards . But now gravity tends to draw it back towards , and hence the motion becomes a retarded one; the velocity continually diminishes, and is ultimately destroyed at some point , which would be at a distance from equal to that of , but for the existence of friction, resistance of the air, &c., which make that distance less. From it will next move down with accelerated motion towards , where it will have its greatest velocity in the direction from left to right, and whence it will pass onwards towards , and so on. Thus the body will vibrate to and fro on either side of , its amplitude of vibration or distance between its extreme positions gradually diminishing in consequence of the resistances before mentioned, and at last being sensibly reduced to nothing, the body then resuming its equilibrium-position .

If the amplitude of vibration is restricted within inconsiderable limits, it is easy to prove that the motion takes place just as if the string were removed, the ball deprived altogether of weight and urged by a force directed to the point , and proportional to the distance from that point. For then, if be any position of the ball, the chord may be regarded as coincident with the tangent to the circle at , and therefore as being perpendicular to . Hence , acting parallel to , being resolved along and , the former component is counteracted by the tension of the string, and there remains as the only effective acceleration, the tangential component along , which, by the triangle of forces, is equal to or , and is therefore proportional to .

On this supposition of indefinitely small vibrations, the pendulum is isochronous; that is, the time occupied in passing from one extreme position to the other is the same, for a given length of the pendulum, whatever the extent of vibration.

We conclude from this that, whatever may be the nature of the forces by which a particle is urged, if the resultant of those forces is directed towards a fixed point, and is proportional to the distance from that point, the particle will oscillate to and fro about that point in times which are independent of the amplitudes of the vibrations, provided these are very small.

5.The particle, whose vibratory motion we have been considering, is a solitary particle acted on by external forces. But, in acoustics, we have to do with the motion of particles forming a connected system or medium, in which the forces to be considered arise from the mutual actions of the particles. These forces are in equilibrium with each other when the particles occupy certain relative positions. But, if any new or disturbing force act for a short time on any one or more of the particles, so as to cause a mutual approach or a mutual recession, on the removal of the disturbing force, the disturbed particles will, if the body be elastic, forthwith move towards their respective positions of equilibrium. Hence arises a vibratory motion to and fro of each about a given point, analogous to that of a pendulum, the velocity at that point being always a maximum, alternately in opposite directions. Thus, for example, if to one extremity of a pipe containing air were applied a piston, of section equal to that of the pipe, by pushing in the piston slightly and then removing it, we should cause particles of air, forming a thin section at the extremity of the pipe, to vibrate in directions parallel to its axis.

In order that a medium may be capable of molecular vibrations, it must, as we have mentioned, possess elasticity, that is, a tendency always to return to its original condition when slightly disturbed out of it.

6.We now proceed to show how the disturbance whereby certain particles of an elastic medium are displaced from m of their equilibrium-positions, is successively transmitted to the remaining particles of the medium, so as to cause these also to vibrate to and fro.

Let us consider a line of such particles & .

equidistant from each other, as above; and suppose one of them, say , to be displaced, by any means, to . As we have seen, this particle will swing from to and back again, occupying a certain time , to complete its double vibration. But it is obvious that, the distance between and the next particle to the right being diminished by the displacement of the former to , a tendency is generated in to move towards , the mutual forces being no longer in equilibrium, but having a resultant in the direction . The particle will therefore also suffer displacement, and be compelled to swing to and fro about the point . For similar reasons the particles will all likewise be thrown into vibration. Thus it is, then, that the disturbance propagates itself in the direction under consideration. There is evidently also, in the case supposed, a transmission from to &c., i.e., in the opposite direction.

Confining our attention to propagation in the direction , we have next to remark that each particle in that line will be affected by the disturbance always later than the particle immediately preceding it, so as to be found in the same stage of vibration a certain interval of time after the preceding particle.

7.Two particles which are in the same stage of vibration, that is, are equally displaced from their equilibrium-positions, and are moving in the same direction and with equal velocities, are said to be in the same phase. Hence we may express the preceding statement more briefly thus: Two particles of a disturbed medium at different distances from the centre of disturbance, are in the same phase at different times, the one whose distance from that centre is the greater being later than the other.

8.Let us in the meantime assume that, the intervals being equal, the intervals of time which elapse between the like phases of and , of and are also equal to each other, and let us consider what at any given instant are the appearances presented by the different particles in the row.

being the time of a complete vibration of each particle, let be the interval of time requisite for any phase of to pass on to . If then at a certain instant is displaced to its greatest extent to the right, will be somewhat short of, but moving towards, its corresponding position, still further short, and so on. Proceeding in this way, we shall come at length to a particle , for which the distance , which therefore lags in its vibrations behind a by a time , and is consequently precisely in the same phase as . And between these two particles we shall evidently have particles in all the possible phases of the vibratory motion. At , which is at distance from , the difference of phase, compared with , will be , that is, will, at the given instant, be dis placed to the greatest extent on the opposite side of its equilibrium-position from that in which is displaced; in other words, is in the exactly opposite phase to .

9.In the case we have just been considering, the vibrations of the particles have been supposed to take place in a direction coincident with that in which the disturbance passes from one particle to another. The vibrations are then termed longitudinal.

But it need scarcely be observed that the vibrations may take place in any direction whatever, and may even be curvilinear. If they take place in directions at right angles to the line of progress of the disturbance, they are said to be transversal.

10.Now the reasoning employed in the preceding case will evidently admit of general application, and will, in particular, hold for transversal vibrations. Hence if we mark (as is done in fig. 2) the positions , occupied by the various particles, when swinging transversely, at the instant at which has its maximum displacement above its equilibrium-position, and trace a continuous line running through the points so found, that line will by its ordinates indicate to the eye the state of motion at the given instant.

Fig. 2.

Thus and are in the same phase, as are also and and , &c. and are in opposite phases, as are also and and , &c.

Distances &c., separating particles in the same phase, and each of which, as we have seen, is passed over by the disturbance in the time of a complete vibration, include within them all the possible phases of the motion.

Beyond this distance, the curve repeats itself exactly, that is, the phases recur in the same order as before.

Now the figure so traced offers an obvious resemblance to the undulating surface of a lake or other body of water, after it has been disturbed by wind, exhibiting a wave with its trough , and its crest . Hence have been introduced into Acoustics, as also into Optics, the terms wave and undulation. The distance , or or , which separates two particles in same phase, or which includes both a wave-crest and a wave-trough, is termed the length of the wave, and is usually denoted .

As the curve repeats itself at intervals each , it follows that particles are in the same phase at any given moment, when the distances between them in the direction of transmission of the disturbance and generally , where is any whole number.

Particles such as and , and , &c., which are at distances , being in opposite phases, so will also be particles separated by distance, ,or, in general, by , that is, by any odd multiple of

11.A like construction to the one just adopted for the displacements of the particles at any given instant, may be also applied for exhibiting graphically their velocities at the same instant. Erect at the various points &c., perpendiculars to the line joining them, of lengths proportional to and in the direction of their velocities, and draw a line through the extreme points of these perpendiculars; this line will answer the purpose required. It is indicated by dots in the previous figure, and manifestly forms a wave of the same length as the wave of displacements, but the highest and lowest points of the one wave correspond to the points in which the other wave crosses the line of equilibrium.

12.In order to a graphic representation of the displacements and velocities of particles vibrating longitudinally, it is convenient to draw the lines which represent those quantities, not in the actual direction in which the motion takes place and which coincides with the line , but at right angles to it, ordinates drawn upwards indicating displacements or velocities to the right (i.e., in the direction of transmission of the disturbance), and ordinates drawn downwards indicating displacements or velocities in the opposite direction. When this is done, waves of dis placement and velocity are figured identically with those for transversal vibrations, and are therefore subject to the same resulting laws.

13.But not only will the above waves enable us to see at a glance the circumstances of the vibratory motion at the instant of time for which it has been constructed, but also for any subsequent moment. Thus, if we desire to consider what is going on after an interval , we have simply to conceive the whole wave (whether of displacement or velocity) to be moved to the right through a distance . Then the state of motion in which a was before will have been transferred to , that of will have been transferred to , and so on. At the end of another such interval, the state of the particles will in like manner be represented by the wave, if pushed onward through another equal space. In short, the whole circumstances may be pictured to the eye by two waves (of displacement and of velocity) advancing continuously in the line with a velocity which will take it over the distance in the time being therefore or .

This is termed the velocity of propagation of the wave, and, as we see, is equal to the length of the wave divided by the time of a complete vibration of each particle.

If, as is usually more convenient, we express in terms of the number of complete vibrations performed in a given time, say in the unit of time, we shall have , and hence

14.There is one very important distinction between the two cases of longitudinal and of transversal vibrations which now claims our attention, viz., that whereas vibrations of the latter kind, when propagated from particle to particle in an elastic medium, do not alter the relative distances of the particles, or, in other words, cause no change of density throughout the medium; longitudinal vibrations, on the other hand, by bringing the particles nearer to or further from one another than they are when undisturbed, are necessarily accompanied by alternate condensations and rarefactions.

Thus, in fig. 2, we see that at the instant to which that fig. refers, the displacements of the particles immediately adjoining are equal and in the same direction; hence at that moment the density of the medium at a is equal to that of the undisturbed medium. The same applies to the points &c., in which the displacements are at their maxima and the velocities of vibration .

At any point, such as , between and , the displacements of the two adjoining particles on either side are both to the right, but that of the preceding particle is now the greater of the two, and hence the density of the medium throughout exceeds the undisturbed density. So at any point, such as , between and , the same result holds good, because now the displacements are to the left, but are in excess on the right side of the point . From to , therefore, the medium is condensed.

From to , as at , the displacements of the two particles on either side are both to the left, that of the preceding particle being, however, the greater. The medium, therefore, is here in a state of rarefaction. And in like manner it may be shown that there is rarefaction from to ; so that the medium is rarefied from to .

At the condensation is a maximum, because the displacements on the two sides of that point are equal and both directed towards . At , on the other hand, it is the rarefaction which is a maximum, the displacements on the right and left of that point being again equal, but directed outwards from .

It clearly follows from all this that, if we trace a curve of which any ordinate shall be proportional to the difference between the density of the corresponding point of the disturbed medium and the density of the undisturbed medium—ordinates drawn upwards indicating condensation, and ordinates drawn downwards rarefaction—that curve will cross the line of rest of the particles in the same points as does the curve of velocities, and will therefore be of the same length , and will also rise above that line and dip below it at the same parts. But the connection between the wave of condensation and rarefaction and the wave of velocity, is still more intimate, when the extent to which the particles are displaced is very small, as is always the case in acoustics. For it may be shown that then the degree of condensation or rarefaction at any point of the medium is proportional to the velocity of vibration at that point. The same ordinates, therefore, will represent the degrees of condensation, which represent the velocities, or, in other words, the wave of condensation and rarefaction may be regarded as coincident with the velocity wave.

Part II.

Velocity of propagation of waves of longitudinal disturbance through any elastic medium.

15.Sir Isaac Newton was the first who attempted to determine, on theoretical grounds, the velocity of sound in air and other fluids. The formula obtained by him gives, however, a numerical value, as regards air, falling far short of the result derived from actual experiment; and it was not till long afterwards, when Laplace took up the question, that complete coincidence was arrived at between theory and observation. We are indebted to the late Professor Rankine, of Glasgow (Phil. Trans. 1870, p. 277)[1], for a very simple and elegant investigation of the question, which we will here reproduce in an abridged form.

Let us conceive the longitudinal disturbance to be propagated through a medium contained in a straight tube having a transverse section equal to unity, but of indefinite length.

Fig. 3.

Let two transverse planes (fig. 3) be conceived as moving along the interior of the tube in the same direction and with the same velocity as the disturbance-wave itself.

Let be the velocities of displacement of the particles of the medium at respectively, at any given instant, estimated in the same direction as ; and the corresponding densities of the medium.

The disturbances under consideration, being such as preserve a permanent type throughout their propagation, it follows that the quantity of matter between , and remains constant during the motion of these planes, or that as much must pass into the intervening space through one of them as issues from it through the other. Now at the velocity of the particles relatively to itself is inwards, and consequently there flows into the space through a mass in the unit of time.

Forming a similar expression as regards , putting for the invariable mass through which the disturbance is propagated in the unit of time, and considering that if denote the density of the undisturbed medium, is evidently equal to , we have—

Now, being the pressures at respectively, and therefore the force generating the acceleration , in unit of time, on the mass of the medium, by the second law of motion,

Eliminating from these equations, and putting for, the symbols (which therefore denote the volumes of the unit of mass of the disturbed medium at , and of the undisturbed medium), we get:

Now, if (as is generally the case in sound) the changes of pressure and volume occurring during the disturbance of the medium are very small, we may assume that these changes are proportional one to the other. Hence, denoting the ratio which any increase of pressure bears to the diminution of the unit of volume of the substance, and which is termed the elasticity of the substance, by , we shall obtain for the velocity of a wave of longitudinal displacements, supposed small, the equation:

| or |

16.In applying this formula to the determination of the velocity of sound in any particular medium, it is requisite, as was shown by Laplace, to take into account the thermic effects produced by the condensations and rarefactions which, as we have seen, take place in the substance. The heat generated during the sudden compression, not being conveyed away, raises the value of the elasticity above that which otherwise it would have, and which was assigned to it by Sir Isaac Newton.

Thus, in a perfect gas, it is demonstrable by the principles of Thermodynamics, that the elasticity , which, in the undisturbed state of the medium, would be simply equal to the pressure , is to be made equal to , where is a number exceeding unity and represents the ratio of the specific heat of the gas under constant pressure to its specific heat at constant volume.

Hence, as air and most other gases may be practically regarded as perfect gases, we have for them:

17.From this the following inference may be drawn:—The velocity of sound in a given gas is unaffected by change of pressure if unattended by change of temperature. For, by Boyle's law, the ratio is constant at a given temperature. The accuracy of this inference has been confirmed by recent experiments of Regnault.

18.To ascertain the influence of change of temperature on the velocity of sound in a gas, we remark that, by Gay Lussac's law, the pressure of a gas at different temperatures varies proportionally both to its density and to , where is the number of degrees of temperature above freezing point of water (32° Fahr.), and is the expansion of unit of volume of the gas for every degree above 32°.

If, therefore, denote the pressures and densities corresponding to temperatures and , we have:

and hence, denoting the corresponding velocities of sound by , we get:

whence, being always a very small fraction, is obtained very nearly:

The velocity increases, therefore, by for every degree of rise of temperature above 32°.

19.The general expression for given in (II.) may be put in a different form: if we introduce a height of the gas, regarded as having the same density throughout and exerting the pressure , then , where is the acceleration of gravity, and there results:

Now or is the velocity which would be acquired by a body falling in vacuo from a height . Hence .

If were equal to , which is the result obtained by Newton, and would indicate that the velocity of sound in a gas equals the velocity of a body falling from a height equal to half of that of a homogeneous atmosphere of the gas.

20.In common dry air at , being , and the mercurial barometer or , the density of air is to that of mercury as ; hence

Also Hence

and, by § 18, the increase of velocity for each degree of rise of temperature ( being ) is or , very nearly.

21.If the value of were the same for different gases, it is obvious from formula that, at a given temperature, the velocities of sound in those gases would be to each other inversely as the square roots of their densities. Regnault has found that this is so for common air, carbonic acid, nitrous oxie, hydrogen and ammoniacal gas (though less so as regards the two last).

22.The experimental determination of the velocity of sound in air has been carried out by ascertaining accurately the time intervening between the flash and report of a gun as observed at a given distance, and dividing the distance by the time. A discussion of the many experiments conducted on this principle in various countries and at various periods, by Van Der Kolk (Lond. and Edin. Phil. Mag., July 1865), assigns to the velocity of sound in dry air at , per second, with a probably error of ; and still more recently (in 1871) Mr Stone, the Astronomer Royal at the Cape of Good Hope, has found 1090.6 as the result of careful experiments by himself there. The coincidence of these numbers with that we have already obtained theoretically sufficiently establishes the general accuracy of the theory.

23.Still it cannot be overlooked that the formula for is founded on assumptions which, though approximately, are not strictly correct. Thus, the air is not a perfect gas, nor is the variation of elastic force, caused by the passage comparison with the elastic force of the undisturbed air. Earnshaw (1858) first drew attention to these points, and came to the conclusion that the velocity of sound increases with its loudness, that is, with the violence of the disturbance. In confirmation of this statement, he appeals to a singular fact, viz., that, during experiments made by Captain Parry, in the North Polar Regions, for determining the velocity of sound, it was invariably found that the report of the discharge of cannon was heard, at a distance of miles, perceptibly earlier than the sound of the word fire, which, of course, preceded the discharge.

As, in the course of propagation in unlimited air, there is a gradual decay in the intensity of sound, it would follow that the velocity must also gradually decrease as the sound proceeds onwards. This curious inference has been verified experimentally by Regnault, who found the velocity of sound to have decreased by per second in passing from a distance of to one of .

24.Among other interesting results, derived by the accurate methods adopted by Regnault, but which want of space forbids us to describe, may be mentioned the dependence of the velocity of sound on its pitch, lower notes being, cæt. par., transmitted at a more rapid rate than higher ones. Thus, the fundamental note of a trumpet travels faster than its harmonies.

25.The velocity of sound in liquids and solid (the displacements being longitudinal), may be obtained by formula (I.), neglecting the thermic effects of the compressions and expansions as being comparatively inconsiderable, and may be put in other forms:

Thus, if we denote by the change in length of one foot of a column of the substance produced by its own weight , then being or , we have and hence:

or, replacing (which is the length in feet of a column that would be increased by the weight of ) by ,

which shows that the velocity is that due to a fall through .

Or, again, in the case of a liquid, if denote the change of volume, which would be produced by an increase of pressure equal to one atmosphere, or to that of a column of the liquid, since is the change of volume due to weight of a column of the liquid, and and , we get

Ex. 1.For water, very nearly; and hence

This number coincides very closely with the value obtained, whether by direct experiment, as by Colladon and Sturm on the Lake of Geneva in 1826, who found , or by indirect means which assign to the velocity in the water of the River Seine at a velocity of (Wertheim).

Ex. 2.For iron. Let the weight necessary to double the length of an iron bar be millions of lbs. on the square foot. Then a length will be extended to by a force of on the sq. ft. This, therefore, by our definition of , must be the weight of a cubic foot of the iron. Assuming the density of iron to be , and as the weight of a cubic foot of water, we get or as the weight of an equal bulk of iron. Hence and , which gives or feet per second nearly.

As in the case of water and iron, so, in general, it may be stated that sound travels faster in liquids than in air, and still faster in solids, the ratio being least in gases and greatest in solids.

26.Biot, about 50 years ago, availed himself of the great difference in the velocity of the propagation of sound through metals and through air, to determine the ratio of the one velocity to the other. A bell placed near one extremity of a train of iron pipes forming a joint length of upwards of , being struck at the same instant as the same extremity heard first the sound of the blow on the pipe, conveyed through the iron, and then, after an interval of time, which was noted as accurately as possible, the sound of the bell transmitted through the air. The result was a velocity for the iron of time that in air. Similar experiments on iron telegraph wire, made more recently near Paris by Wertheim and Brequet, have led to an almost identical number. Unfortunately, owing to the metal in those experiments not forming a continuous whole, and to other causes, the results obtained, which fall short of those otherwise found, cannot be accepted as correct.

Other means therefore, of an indirect character, to which we will refer hereafter, have been resorted to for determining the velocity of sound in solids. Thus Wertheim, from the pitch of the lowest notes produced by longitudinal friction of wires or rods, has been led to assign to that velocity values ranging, in different metals, from for iron, to for lead, at temperature , and which agree most remarkably with those calculated by means of the formula . He points out, however, that these values refer only to solids whose cross dimensions are small in comparison with their length, and that in order to obtain the velocity of sound in an unlimited solid mass, it is requisite to multiply the value as above found by or nearly. For while, in a solid bar, the extensions and contractions due to any disturbance take place laterally as well as longitudinally; in an extended solid, they can only occur in the latter direction, thus increasing the value of .

27.To complete the discussion of the velocity of the propagation of sound, we have still to consider the case of transversal vibrations, such as are executed by the points of a stretched wire or cord when drawn out of its position of rest by a blow, or by the friction of a violin-bow.

Fig. 4.

Let (fig. 4) be the position of the string when undisturbed, when displaced. We will suppose the amount of displacement to be very small, so that we may regard the distance between any two given points of it as remaining the same, and also that the tension of the string is not changed in its amount, but only in its direction, which is that of the string.

Take any origin in , and ( very small quantity), then the perpendiculars , are the displacements of . Let be the middle points of ; then (which or very nearly) may be regarded as a very small part of the string acted on by two forces each , and acting at in the directions . These give a component parallel to , which on our supposition is negligible, and another along , such that

Now if a length of string of weight equal to , and the string to be supposed of uniformed thickness and density, the weight of , and the mass of .

Hence the acceleration in direction is—

If we denote by , by , and the time by , we shall readily see that this equation becomes ultimately,

which is satisfied by putting

where and indicate any functions.

Now we know that if for a given value of , be increased by the length of the wave, the value of remains unchanged; hence,

But this condition is equally satisfied for a given value of , by increasing by , i.e., increasing by . This therefore must (the time of a complete vibration of any point of the string). But . Hence,

is the expression for the velocity of sound when due to very small transversal vibrations of a thin wire or chord, which velocity is consequently the same as would be acquired by a body falling through a height equal to one half of a length of the chord such as to have a weight equal to the tension.

The above may also be put in the form:—

where is the tension, and the weight of the unit of length of the chord.

28.It appears then that while sound is propagated by longitudinal vibrations through a given substance with the same velocity under all circumstances, the rate of its transmission by transversal vibrations through the same substance depends on the tension and on the thickness. The former velocity bears to the latter the ratio of , (where is the length of the substance, which would be lengthened one foot by the weight of one foot, if we take the foot as our unit) or of , that is, of the square root of the length which would be extended one foot by the weight of feet, or by the tension, to . This, for ordinary tensions, results in the velocity for longitudinal vibrations being very much in excess of that for transversal vibrations.

29.It is a well known fact that, in all but very exceptional cases, the loudness of any sound is less as the distance increases between the source of sound and the ear. The law according to which this decay takes place is the same as obtains in other natural phenomena, viz., that in an unlimited and uniform medium the loudness or intensity of the sound proceeding from a very small sounding body (strictly speaking, a point) varies inversely as the square of the distance.

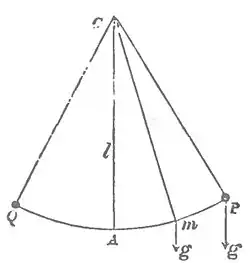

Fig. 5.

This follows from considering that the ear receives only the conical portion of the whole volume of sound emanating from , and that in order that an ear , placed at a greater distance from , may admit the same quantity, its area must be to that of as . But if be situated at same distance as , the amount of sound received by it and by (and therefore by will be as the area of or to that of . Hence, the intensities of the sound as heard by the same ear at the distances and are to each other as to .

30.In order to verify the above law when the atmosphere forms the intervening medium, it would be necessary density of to test it at a considerable elevation above the earth's the air on surface, the ear and the source of sound being separated by air of constant density. As the density of the air diminishes, we should then find that the loudness of the sound at a given distance would decrease, as is the case in the air-pump experiment previously described. This arises from the decrease of the quantity of matter impinging on the ear, and the consequent diminution of its vis-viva. The decay of sound due to this cause is observable in the rarefied air of high mountainous regions. De Saussure, the celebrated Alpine traveller, mentions that the report of a pistol at a great elevation appeared no louder than would a small cracker at a lower level.

But it is to be remarked that, according to Poisson, when air-strata of different densities are interposed between the source of sound and the ear placed at a given distance, the intensity depends only on the density of the air at the source itself; whence it follows that sounds proceeding from the surface of the earth may be heard at equal distances as distinctly by a person in a floating balloon as by one situated on the surface itself; whereas any noise originating in the balloon would be heard at the surface as faintly as if the ear were placed in the rarefied air on a level with the balloon. This was exemplified during a balloon ascent by Glaishor and Coxwell, who, when at an elevation of feet, heard with great distinctness the whistle of a locomotive passing beneath them.

Part III.

Reflexion and Refraction of Sound.

31.When a wave of sound travelling through one refraction, medium meets a second medium of a different kind, the vibrations of its own particles are communicated to the particles of the new medium, so that a wave is excited in the latter, and is propagated through it with a velocity dependent on the density and elasticity of the second medium, and therefore differing in general from the previous velocity. The direction, too, in which the new wave travels is different from the previous one. This change of direction is termed refraction, and takes place according to the same laws as does the refraction of light, viz., (1.) The new direction or refracted ray lies always in the plane of incidence, or plane which contains the incident ray (i.e., the direction of the wave in the first medium), and the normal to the surface separating the two media, at the point in which the incident ray meets it; (2.) The sine of the angle between the normal and the incident ray bears to the sine of the angle between the normal and the refracted ray, a ratio which is constant for the same pair of media.

For a theoretical demonstration of these laws, we must refer to the art. Optics, where it will be shown that the ratio involved in the second law is always equal to the ratio of the velocity of the wave in the first medium to the velocity in the second; in other words, the sines of the angles in question are directly proportional to the velocities.

Fig. 6.

32.Hence sonorous rays, in passing from one medium into another, are bent in towards the normal, or the reverse, according as the velocity of propagation in the former exceeds or falls short of that in the latter. Thus, for instance, sound is refracted towards the perpendicular when passing into air from water, or into carbonic acid gas from air; the converse is the case when the passage takes place the opposite way.

33.It further follows, as in the analogous case of light, that there is a certain angle termed the limiting angle, whose sine is found by dividing the less by the greater velocity, such that all rays of sound meeting the surface separating two different bodies will not pass onward, but surfer total reflexion back into the first body, if the velocity in that body is less than that in the other body, and if the angle of incidence exceeds the limiting angle.

The velocities in air and water being respectively and feet, the limiting angle for these media may be easily shown to be slightly above . Hence, rays of sound proceeding from a distant source, and therefore nearly parallel to each other, and to (fig. 6), the angle being greater than , will not pass into the water at all, but suffer total reflexion. Under such circumstances, the report of a gun, however powerful, would be inaudible by an ear placed in the water.

34.As light is concentrated into a focus by a convex glass lens (for which the velocity of light is less than for the air), so sound ought to be made to converge by passing through a convex lens formed of carbonic acid gas. On the other hand, to produce convergence with water or hydrogen gas, in both which the velocity of sound exceeds its rate in air, the lens ought to be concave. These results have been confirmed experimentally by Sondhaus and Hajech, who also succeeded in verifying the law of the equality of the index of refraction to the ratio of the velocities of sound.

35.When a wave of sound falls on a surface separating two media, in addition to the refracted wave transmitted into the new medium, which we have just been considering, there is also a fresh wave formed in the new medium, and travelling in it in a different direction, but, of course, with the same velocity. This reflected wave is subject to the same laws as regulate the reflexion of light, viz., (1.) the coincidence of the planes of incidence and of reflexion, and (2.) the equality of the angles of incidence and reflexion, that is, of the angles made by the incident and reflected rays with the normal.

Fig. 7.

36.As in an ellipse (fig. 7), the normal at any point by a bisects the angle ( being the foci), rays of sound diverging from , and falling on the spheroidal surface formed by the revolution of the ellipse about the longest diameter , will be reflected to . Also, since is always , the times in which the different rays will reach H will all be equal to each other, and hence a crash at will be heard as a crash at .

37.At any point of a parabola (fig. 8) of which is the focus, and the axis, the normal bisects the by par angle , being drawn parallel to . Hence rays of sound diverging from , and falling on the paraboloid formed by the revolution of the parabola about its axis, will all be reflected in directions parallel to the axis. And vice versa rays of sound , , &c., from a very distant source, and parallel to the axis of a paraboloid, will be reflected into the focus. Consequently, if two reflecting paraboloids be placed at a considerable distance from and opposite to each other, with their axis coincident in direction (fig. 9), the tick of a watch placed at the focus of one will be heard distinctly by an ear at , the focus of the other. 38.As a luminous object may give a succession of images when placed between two or more reflecting surfaces, so also in like circumstances may a sound suffer repetition.

Fig. 9.

To these principles are easily traceable all the peculiarities of echoes. A wall or steep cliff may thus send back, somewhat reduced in intensity, a shout, the report of a pistol, &c. The time which elapses between the sound and its echo may be easily deduced from the known velocity of sound in air, if the distance of the wall be given. Thus, for a distance of yards, the interval will be found by dividing the double of that or yard by yards, the velocity of sound at Fahr., to amount to of a second. Hence, if we assume that the rate at which syllables can be distinctly uttered is five per second, the wall must be at a distance exceeding yards to allow of the echo of a word of one syllable reaching the ear after the word has been uttered, yards for a word of two syllables, and so on.

If the reflecting surface consists of one or more walls, cliffs, &c., forming together a near approach in shape to that of a prolate spheroid or of a double parabolic surface, then two points may be found, at one of which if a source of sound be placed, there will be produced, by convergence, a distinct echo at the other. As examples of this may be mentioned the whispering gallery in St Paul's, London, and the still more remarkable case of the Cathedral of Girgenti in Sicily mentioned by Sir John Herschel.

39.On similar principles of repeated reflexion may be explained the well-known fact that sounds may be conveyed to great distances with remarkably slight loss of intensity, on a level piece of ground or smooth sheet of water or ice, and still more so in pipes, chimneys, tunnels, &c. Thus, in one of Captain Parry's Polar expeditions, a conversation was on one occasion carried on, at a distance of mile, between two individuals separated by a frozen sheet of water. M. Biot heard distinctly from one end of the train of pipes of a mile long, previously referred to, a low whisper proceeding from the opposite end.

Practical illustrations are afforded by the system of communication by means of tubing now so extensively adopted in public and private buildings, and by the speaking trumpet and the ear trumpet.

40.The prolonged roll of thunder, with its manifold varieties, is partly to be ascribed to reflexion by mountains, clouds, &c.; but is mainly accounted for on a different acoustic principle, viz., the comparatively low rate of transmission of sound through air, as was first shown by Dr Hooke at the close of the 17th century. The explanation will be more easily understood by adverting to the case of a volley fired by a long line of troops. A person situated at a point in that line produced, will first it is evident hear the report of the nearest musket, followed by that of the one following, and so down to the last one in the line, which will close the prolonged roll thus reaching his ear; and as each single report will appear to him less intense according as it proceeds from a greater distance, the roll of musketry thus heard will be one of gradually decreasing loudness. But if he were to place himself at a relatively great distance right opposite to the centre of the line, the separate reports from each of the two wings would reach him nearly at the same moment, and hence the sound of the volley would now approach more nearly to that of a single loud crash. If the line of soldiers formed an arc of a circle having its centre in his position, then the distances gone over by the separate reports being equal, they would reach his ear at the same absolute instant of time, and wit exactly equal intensities; and the effect produced would be strictly the same as that of a single explosion, equal in violence to the sum of all the separate discharges, occurring at the same distance. It is easy to see that, by varying the form of the line of troops and the position of the observer, the sonorous effect will be diversified to any extent desired. If then we keep in view the great diversity of form exhibited by lightning-flashes, which may be regarded as being lines, at the points of which are generated explosions at the same instant of time, and the variety of distance and relative position at which the observer may be placed, we shall feel no difficulty in accounting for all those acoustic phenomena of thunder to which Hooke's theory is applicable.

Part IV.

The Principles of Musical Harmony.

41.A few words on the subject of musical harmony must be introduced here for the immediate purposes of this article, further details being reserved for the special article on that subject.

Sounds in general exhibit three different qualities, so far as their effect on the ear is concerned, viz., loudness, pitch, and timbre.

Loudness depends, cæt. par., on the violence with which the vibrating portions of the ear are excited; and therefore on the extent or amplitude of the vibrations of the body whence the sound proceeds. Hence, after a bell has been struck, its effect on the ear gradually diminishes as its vibrations, loudness or intensity is measured by the vis-viva of the vibrating particles, and is consequently proportional to the square of their maximum velocity or to the square of their maximum displacement. Helmholtz, however, in his remarkable work on the perception of tine, observes that notes differing in pitch differ also in loudness, where their vis-viva is the same, the higher note always exhibiting the greater intensity.

42.Difference of pitch is that which finds expression in the common terms applied to notes: Acute, shrill, high, sharp, grave, deep, low, flat. We will point out presently in what manner it is established that this quality of sound depends on the rapidity of vibration of the particles of air in contact with the external parts of the ear. The pitch of a note is higher in proportion to the number of vibrations of the air corresponding to it, in a given time, such as one second. If denote this number, then, by § 13, , and hence, being constant, the pitch is higher the less the length of the wave.

43.Timbre, or, as it is termed by German authors, klang-farbe, rendered by Tyndall into clang-colour or clang-tint, but for which we would substitute the expression acoustic colour, denotes that peculiarity of impression produced on the ear by sounds otherwise, in pitch, loudness, &c., alike, whereby they are recognisable as different from each other. Thus human voices are readily interdistinguishable; so are notes of the same pitch and intensity, produced by different instruments. The question whence arises this distinction must be deferred for the present.

44.Besides the three qualities above mentioned, there exists another point in which sounds may be distinguished among each other, and which, though perhaps reducible to difference of timbre, requires some special remarks, viz., that by which sounds are characterised, either as noises or as musical notes. A musical note is the result of regular, periodic vibrations of the air-particles acting on the ear, and therefore also of the body whence they proceed, each particle passing through the same phase at stated intervals of time. On the other hand, the motion to which noise is due is irregular and flitting, alternately fast and slow, and creating in the mind a bewildering and confusing effect of a more or less unpleasant character. Noise may also be produced by combining in an arbitrary manner several musical notes, as when one leans with the fore-arm against the keys of a piano. In fact, the composition of regular periodic motions, thus effected, is equivalent to an irregular motion.

45.We now proceed to state the laws of musical harmony, and to describe certain instruments by means of which they admit of being experimentally established. The chief of these laws are as follows:—

(1.)The notes employed in music always correspond to certain definite and invariable ratios between the numbers of vibrations performed in a given time by the air when conveying these notes to the ear, and these ratios are of a very simple kind, being restricted to the various permutations of the first four prime numbers , and their powers.

(2.)Two notes are in unison whose corresponding vibrations are executed exactly at the same rate, or for which (denoting by the numbers per second) . This ratio or interval (as it is termed) is the simplest possible.

(3.)The next interval is that in which , and is termed the octave.

(4.)The interval is termed the twelfth, and if we reduce the higher note of the pair by an 8ve, i.e., divide its number of vibrations by , we obtain the interval , designated as the interval of the fifth.

(5.)The interval has no particular name attached to it, but if we lower the higher note by two 8ves or divide by , we get the interval , or the interval of the major third.

(6).The interval is termed the major sixth.

(7.)The interval is termed the minor third.

(8.)The interval is termed the fourth.

(9.)The interval which, being , may be regarded as formed by taking in the first place a note one-fifth higher than the key-note or fundamental, i.e., higher than the latter by the interval , thence ascending by another fifth, which gives us and lowering this by an octave, which results in , which is called the second.

(10.)The interval or may be regarded as the major third of the fifth , and is called the interval of the seventh.

46.If the key-note or fundamental be denoted by , and the notes, whose intervals above are those just enumerated, by , , , , , , , we form what is known in music as the natural or diatonic scale, in which therefore the intervals reckoned from are successively

and therefore the intervals between each note and the one following are

Of these last intervals the first, fourth, and sixth are each , which is termed a major tone. The second and fifth are each , which is a ratio slightly less than the former, and hence is called a minor tone. The third and seventh are each , to which is given the name of semi-tone.

By interposing an additional note between each pair of notes whose interval is a major or a minor tone, the resulting series of notes may be made to exhibit a nearer approach to equality in the intervals successively separating them, which will be very nearly semi-tones. This sequence of twelve notes forms the chromatic scale. The note interposed between and is either sharp (♯) or flat (♭), according as it is formed by raising a semi-tone or lowering by the same amount.

47.Various kinds of apparatus have been contrived with a view of confirming experimentally the truth of the laws of musical harmony as above stated.

Savart's toothed wheel apparatus consists of a brass wheel, whose edge is divided into a number of equal projecting teeth distributed uniformly over the circumference, and which is capable of rapid rotation about an axis perpendicular to its plane and passing through its centre, by means of a series of multiplying wheels, the last of which is turned round by the hand. The toothed wheel being set in motion, the edge of a card or of a funnel-shaped piece of common note paper is held against the teeth, when a note will be heard arising from the rapidly succeeding displacements of the air in its vicinity. The pitch of this note will, agreeably to the theory, rise as the rate of rotation increases, and becomes steady when that rotation increases, and becomes steady when that rotation is maintained uniform. It may thus be brought into unison with any sound of which it may be required to determine the corresponding number of vibrations per second, as for instance the note , three 8ves higher than the which is indicated musically by a small circle placed between the second and third lines of the clef, which is the note of the tuning-fork usually employed for regulating concert-pitch. may be given by a piano. Now, suppose that the note produced with Savart's apparatus is in unison with , when the experimenter turns round the first wheel the rate of turns per minute or one per second, and that the circumferences of the various multiplying wheels are such that the rate of revolution of the toothed wheel is thereby increased times, then the latter wheel will perform revolutions in a second, and hence, if the number of its teeth be , the number of taps imparted to the card every second will amount to or . This, therefore, is the number of vibrations corresponding to the note . If we divide this by or , we obtain as the number of vibrations answering to the note . This, however, tacitly assumes that the bands by which motion is transmitted from wheel to wheel do not slip during the experiment. If, as is always more or less the case, slipping occurs, a different mode for determining the rate at which the toothed wheel revolves, such as is employed in the syren of De la Tour (vide below), must be adopted.

If, for the single toothed wheel, be substituted a set of four with a common axis, in which the teeth are in the ratios , and if the card be rapidly passed along their edges, we shall hear distinctly produced the fundamental chord , , , and shall thus satisfy ourselves that the intervals , ; , and are (as they ought to be) , , and respectively.

48.The syren of Seeback is the simplest form of apparatus thus designated, and consists of a large circular disc of pasteboard mounted on a central axis, about which it may be made to revolve with moderate rapidity. This disc is perforated with small round holes arranged in circles about the centre of the disc. In the first series of circles, reckoning from the centre, the openings are so made as to divide the respective circumferences, on which they are found, in aliquot parts bearing to each other the ratios of the numbers , , , , , , , , , , , , . The second series consists of circles each of which is formed of two sets of perforations, in the first circle arranged as , in the next as , then as , , . In the outer series is a circle divided by perforations into four sets, the numbers of aliquot parts being as , followed by others which we need not further refer to.

The disc being started, then by means of a tube held at one end between the lips, and applied near to the disc at the other, or more easily with a common bellows, a blast of air is made to fall on the part of the disc which contains any one of the above circles. The current being alternately transmitted and shut off, as a hole passes on and off the aperture of the tube or bellows, causes a vibratory motion of the air, whose rapidity depends on the number of times per second that a perforation passes the mouth of the tube. Hence the note produced with any given circle of holes rises in pitch as the disc revolves more rapidly; and if, the revolution of the disc being kept as steady as possible, the tube be passed rapidly across the circles of the first series, the notes heard are found to produce on the ear, as required by theory, the exact impression corresponding to the rations &c., i.e., of a series of notes, which, if the lowest be denoted by , form the sequence &c., &c. In like manner, the first circle in which we have two sets of holes dividing the circumference, the one into , or in ratio , the note produced is a compound one, such as would be obtained by striking on the piano two notes separated by the interval of a major third . Similar results, all agreeing with the theory, are obtainable by means of the remaining perforations.

A still simpler form of syren may be constituted with a good spinning top, a perforated card disc, and a tube for blowing with.

49.The syren of Cagnard de la Tour is founded on the same principle as the preceding. It consists of a cylindrical chest of brass, the base of which is pierced at its centre with an opening in which is fixed a brass tube projecting outwards, and intended for supplying the cavity of the cylinder with compressed air or other gas, or even liquid. The top of the cylinder is formed of a plate perforated near its edge by holes distributed uniformly in a circle concentric with the plate, and which are cut obliquely through the thickness of the plate.

Fig. 10.

Immediately above this fixed plate, and almost in contact with it, is another of the same dimensions, and furnished with the same dimensions, and furnished with the same number, , of openings similarly placed, but passing obliquely through in an opposite direction from those in the fixed plate, the one set being inclined to the left, the other to the right.

This second plate is capable of rotation about a steel axis perpendicular to its plane and passing through its centre. Now, let the movable plate be at any time in a position such that its holes are immediately above those in the fixed plate, and let the bellows by which air is forced into the cylinder (air, for simplicity, being supposed to be the fluid employed) be put in action; then the air in its passage will strike the side of each opening in the movable plate in an oblique direction (as shown in fig. 10), and will therefore urge the latter to rotation round its centre. After th of a revolution, the two sets of perforations will again coincide, the lateral impulse of the air repeated, and hence the rapidity of rotation increased. This will go on continually as long as air is supplied to the cylinder, and the velocity of rotation of the upper plate will be accelerated up to a certain maximum, at which it may be maintained by keeping the force of the current constant.

Now, it is evident that each coincidence of the perforations in the two plates is followed by a non-coincidence, during which the air-current is shut off, and that consequently, during each revolution of the upper plate, there occur alternate passages and interceptions of the current. Hence arises the same number of successive impulses of the external air immediately in contact with the movable plate, which is thus thrown into a state of vibration at the rate of for every revolution of the plate. The result is a note whose pitch rises as the velocity reaches its constant value. If, then, we can determine the number of revolutions performed by the plate in every second, we shall at once have the number of vibrations per second corresponding to the audible note by multiplying by .

For this purpose the steel axis is furnished at its upper part with a screw working into a toothed wheel, and driving it round, during each revolution of the plate, through a space equal to the interval between two teeth. An index resembling the hand of a watch partakes of this motion, and points successively to the divisions of a graduated dial. On the completion of each revolution of this toothed wheel (which, if the number of its teeth be , will comprise revolutions of the movable plate), a projecting pin fixed to it catches a tooth of another toothed wheel and turns it round, and with it a corresponding index which thus records the number of turns of the first toothed wheel. As an example of the application of this syren, suppose that the number of revolutions of the plate, as shown by the indices, amounts of in a minute of time, that is, to per second, then the number of vibrations per second of the note heard amounts to , or (if number of holes in each plate ) to .

50.Dove, of Berlin, has produced a modification of the syren by which the relations of different musical notes may be more readily ascertained. In it the fixed and movable plates are each furnished with four concentric series of perforations, dividing the circumferences into different aliquot parts, as p. ex., , , , . Beneath the lower or fixed plate are four metallic rings furnished with holes corresponding to those in the plates, and which may be pushed round by projecting pins, so as to admit the air-current through any one or more of the series of perforations in the fixed plate. Thus, may be obtained, either separately or in various combinations, the four notes whose vibrations are in the ratios of the above numbers, and which therefore form the fundamental chord (). The inventor has given to this instrument the name of the many-voiced syren.

51.Helmholtz has further adapted the syren for more extensive use, by the addition to Dove's instrument of another chest containing its own fixed and movable perforated plates and perforated rings, both the moveable plates being driven by the same current and revolving about a common axis. Annexed is a figure of this instrument (fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

52.The relation between the pitch of a note and the frequency of the corresponding vibrations has also been studied by graphic methods. Thus, if an elastic metal slip or a pig's bristle be attached to one prong of a tuning-fork, and if the fork, while in vibration, is moved rapidly over a glass plate coated with lamp black, the attached slip touching the plate lightly, a wavy line will be traced on the plate answering to the vibrations to and fro of the fork. The same result will be obtained with a stationary fork and a movable glass plate; and, if the time occupied by the plate in moving through a given distance can be ascertained, and the number of complete undulations exhibited on the plate for that distance, which is evidently the number of vibrations of the fork in that time, is reckoned, we shall have determined the numerical vibration-value of the note yielded by the fork. Or, if the same plate be moved in contact with two tuning-forks, we shall, by comparing the number of sinuosities in the one trace with that in the other, be enabled to assign the ratio of the corresponding numbers of vibrations per second. Thus, if the one note be an octave higher than the other, it will give double the number of waves in the same distance. The motion of the plate may be simply produced by dropping it between two vertical grooves, the tuning-forks being properly fixed to a frame above.

53.Greater accuracy may be attained with the so-called Vibrograph or Phonautograph (Duhamel's or Kœnig's), consisting of a glass cylinder coated with lamp-black, or, better still, a metallic cylinder round which a blackened sheet of paper is. wrapped. The cylinder is mounted on a horizontal axis and turned round, while the pointer attached to the vibrating body is in light contact with it, and traces therefore a wavy circle, which, on taking off the paper and flattening it, becomes a wavy straight line. The superiority of this arrangement arises from the comparative facility with which the number of revolutions of the cylinder in a given time may be ascertained. In Kœnig's phonautograph, the axis of the cylinder is fashioned as a screw, which works in fixed nuts at the ends, causing a sliding as well as a rotatory motion of the cylinder. The lines traced out by the vibrating pointer are thus prevented from over lapping when more than one turn is given to the cylinder.

Any sound whatever may be made to record its trace on the paper by means of a large parabolic cavity resembling a speaking-trumpet, which is freely open at the wider extremity, but is closed at the other end by a thin stretched membrane. To the centre of this membrane is attached a email feather-fibre, which, when the reflector is suitably placed, touches lightly the surface of the revolving cylinder. Any sound (such as that of the human voice) transmitting its rays into the reflector, and communicating vibratory motion to the membrane, will cause the feather to trace a sinuous line on the paper. If, at the same time, a tuning-fork of known number of vibrations per second be made to trace its own line close to the other, a comparison of the two lines gives the number corresponding to the sound under consideration.

Part V.

Stationary Waves.

54.We have hitherto, in treating of the propagation of waves of sound, assumed that the medium through which it took place was unlimited in all directions, and that the source of sound was single. In order, however, to understand the principles of the production of sound by musical instruments, we must now direct our attention to the case of two waves from different sources travelling through the same medium in opposite directions. Any particle of the medium being then affected by two different vibrations at the same instant will necessarily exhibit a different state of motion from that due to either wave acting separately from the other, and we have to inquire what is the result of this mutual interference (as it is termed) of the two given waves.

Fig. 12.

Supposing, as sufficient for our purpose, that the given waves are of equal lengths and of equal amplitudes, in other words, that the corresponding notes are of the same pitch and equally loud; and supposing, further, that they are advancing in exactly opposite directions, we shall now show that the result of the mutual interference of two such waves is the production of a stationary wave, that is, taking any line of particles of the medium along the direction of motion of the component waves, certain of them, such as , , at intervals each , will remain constantly in their usual undisturbed positions. All the particles situated between and will vibrate (transversely or longitudinally, as the case may be) to and fro in the same direction as they would if affected by only one of the interfering waves, but with different amplitudes of vibration, ranging from zero at to a maximum at and thence to zero at . Those between and will vibrate in like manner, but always in an opposite direction to the similarly placed particles in , and so on alternately.

Fig. 13.

The annexed figures will represent to the eye the states of motion at intervals of time of the time of a complete vibration of the particles. In fig. 13, 1, the particles in ac are at their greatest distances from their undisturbed positions (above or to the right, according as the motion is transversal or longitudinal). In fig. 13, 2, they are all in their undisturbed positions. In fig. 13, 3, the displacements are all reversed relatively to fig. 13, 1. In fig. 13, 4, the particles are again passing through their equilibrium positions, resuming the positions indicated, in fig. 13, 1, after the time .

The points , &c., which remain stationary are termed nodes, and the vibrating parts between them ventral segments.

54a. Proof.In fig. 14, 1, the full curved line represents the two interfering waves at an instant of time such that, in their progress towards each other, they are then coincident, It is obvious that the particles of the medium will at the moment in question be displaced to double the extent of the displacement producible by either wave alone, so that the resultant wave may be represented by the dotted curve.

Fig. 14.

In fig. 14, 2, the two interfering waves, represented by the full and dotted curves respectively, have each passed over a distance , the one to the right, the other to the left, and it is manifest that any disturbance of the medium, producible by the one wave, is completely neutralised by the equal and opposite action of the other. Hence, the particles of the medium are now in their undisturbed positions. In fig. 14, 3, a further advance of the two waves, each in its own direction, over a space , has again brought them into coincidence, and the result is the wave represented by the dotted line, which, it will be re marked, has its crests, where, in fig. 1, are found troughs. In fig. 14, 4, after a further advance , we have a repetition of the case of fig. 14, 2, the particles are now again unaffected by the waves. A still further advance of , or of reckoned from the commencement, brings us back to the same state of things as subsisted in fig. 14, 1. An inspection and inter-comparison of the dotted lines in these figures are now sufficient to establish the accuracy of the laws, before mentioned, of stationary waves.

Part VI.

Musical Strings.

55.We have in musical strings an instance of the occurrence of stationary waves.

Fig. 15.

Let (fig. 15) be a wire or string, supposed meanwhile to be fixed only at one extremity , and let the wire be, at any part, excited (whether by passing a violin bow across or by friction along it), so that a wave (whether of transversal or longitudinal vibrations) is propagated thence towards . On reaching this point, which is fixed, reflexion will occur, in consequence of which the particles there will suffer a complete reversal of velocity, just as when a perfectly elastic ball strikes against a smooth surface perpendicularly, it rebounds with a velocity equal and opposite to that it previously had. Hence, the displacement due to the incident wave being , the displacement after reflexion will be equal and opposite to , and a reflected wave will result, represented by the faint line in the fig., which will travel with the same velocity, but in the opposite direction to the incident wave fully lined in the fig. The interference of these two oppositely progressing waves will consequently give rise to a stationary wave (fig. 16), and if we take on the wire distances , , , &c. , the points , , , , will be nodes, each of which separate portions of the wire vibrating in opposite directions, i.e., ventral segments.

56.Now, it is obvious that, inasmuch as a node is a point which remains always at rest while other parts of the medium to which it belongs are vibrating, such point may be absolutely fixed without thereby interfering with the oscillatory motion of the medium. If, therefore, a length of wire be taken equal to any multiple of , may be fixed as well as , the motion remaining the same as before, and thus we shall have the usual case of a musical string. The two extremities being now both fixed, there will be repeated reflexions at both, and a consequent persistence of two progressive waves advancing in opposite directions and producing together the stationary wave above figured.

57.We learn from this that a musical string is susceptible of an infinite variety of modes of vibration corresponding to different numbers of subdivision into ventral segments.

Thus, it may have but one ventral segment (fig. 17), or but two nodes formed by its fixed extremities. In this case, the note emitted by it is the lowest which can possibly be obtained from it, or, as it is called, its fundamental note. If denote the length of the wire, by what has been already proved, , and therefore the length of the wave . Hence, being the velocity of propagation of the wave through the wire, the number of vibrations performed in the unit of time with the fundamental note is .

The next possible sub-division of the wire is into two ventral segments, the three nodes being the two fixed ends , , and the middle point (fig. 18). Hence, , and the number of vibrations or double of those of the fundamental. The note, therefore, now is an 8ve higher.

Reasoning in a like manner for the cases of three, four, &c., ventral segments, we obtain the following general law, which is applicable alike to transversely and to longitudinally vibrating wires:

A wire or string fixed at both ends is capable of yielding, in addition to its fundamental note, any one of a series of notes corresponding to , , times, &c., the number of vibrations per second of the fundamental, viz., he octave, twelfth, double octave, &c.

These higher notes are termed the harmonics or (by the Germans) the overtones of the string.

It is to be remarked that the overtones are in general fainter the higher they are in the series, because, as the number of ventral segments or independently vibrating parts of the string increases, the extent or amplitude of the vibrations diminishes.

58.Not only may the fundamental and its harmonics be obtained independently of each other, but they are also to be heard simultaneously, particularly, for the reason just given, those that are tower in the scale. A practised ear easily discerns the coexistence of these various tones when a pianoforte or violin string is thrown into vibration.

Fig. 19.

It is evident that, in such case, the string, while vibrating as a whole between its fixed extremities, is at the same time executing subsidiary oscillations about its middle point, its points of trisection, &c., as shown in fig. 19, for the fundamental and the first harmonic.

59.The easiest means for bringing out the harmonics of a string consists in drawing a violin-bow across it near to one end, while the feathered end of a quill or a hair-pencil is held lightly against the string at the point which it is intended shall form a node, and is removed just after the bow is withdrawn. Thus, if a node is made in this way, at of from , the note heard will be the twelfth. If light paper rings be strung on the cord, they will be driven by the vibrations to the nodes or points of rest, which will thus be clearly indicated to the eye.

60.The formula shows that the pitch of the fundamental note of a wire of given length rises with the velocity of propagation of sound through it. Now we have learned (§ 28) that this velocity, in ordinary circumstances, is enormously greater for a wire vibrating longitudinally than for the same wire vibrating transversely. The fundamental note, therefore, is far higher in pitch in the former than in the latter case.

As, however, the quantity depends, for longitudinal vibrations, solely on the nature of the medium, the pitch of the fundamental note of a wire rubbed along its length depends—the material being the same, brass for instance—on its length, not at all on its thickness, &c.

But as regards strings vibrating transversely, such as are met with in our instrumental music, , as we have seen (§ 27), depends not only on the nature of the substance used, but also on its thickness and tension, and hence the pitch of the fundamental, even with the same length of string, will depend on all those various circumstances.

61.If we put for its equivalent expressions before given, we have for the fundamental note note of transversely vibrating strings:

whence the following inferences may be easily drawn:

If a string, its tension being kept invariable, have its length altered, the fundamental note will rise in pitch in exact proportion with its diminished length, that is, varies then inversely as .

Hence, on the violin, by placing a finger successively on any one ot the strings at , we shall obtain notes corresponding to numbers of vibrations bearing to the fundamental the ratios to unity of the following, viz., , , , , , , which notes form, therefore, with the fundamental, the complete scale.

62.By tightening a musical string, its length remaining unchanged, its fundamental is rendered higher. In fact, then, is proportional to the square root of the tension. Thus, by quadrupling the tension, the note is raised an octave. Hence, the use of keys in tuning the violin, the, pianoforte, &c.