Capitalism and the War

CAPITALISM

AND THE WAR

The Economic Aims

of the Great Powers

BY

J. T. WALTON NEWBOLD, M.A.

WITH TWO MAPS

PRICE SIXPENCE

THE NATIONAL LABOUR PRESS. LIMITED,

30, BLACKFRIARS ST., MANCHESTER; and at LONDON,

Capitalism and

the War

The Economic Aims of the

Great Powers

BY

J. T. WALTON NEWBOLD, M.A.

THE NATIONAL LABOUR PRESS, LTD.,

30, BLACKFRIARS STREET, MANCHESTER;

and at London.

THE BRITISH WAR AIMS.

"They (the British Government) did not enter upon this war as a war of conquest, and they are not continuing it for any such object. Their purpose at the outset was to defend the existence of their country and to enforce respect for international engagements. To those objects have now been added that of liberating populations oppressed by alien tyranny. … Beyond everything, we must seek for such a settlement as will secure the happiness and contentment of the peoples and take away all legitimate causes of future war."

[Note sent by British Government to Russian Government, June, 1917.]

THE GERMAN WAR AIMS.

"The four allied Powers were obliged to take up arms to defend justice and the liberty of national evolution. … Our aims are not to shatter nor annihilate our adversaries."

[Note sent by German Government to President Wilson, December, 1916.]

Capitalism and the War.

I.

THE DIVERSE IDEALS OF THE

BELLIGERENTS.

When war broke out, and it became necessary to defend the interests of the British Empire, as well as the territorial integrity of its Allies, our Government and the governments of the other Liberal Powers added to their defensive aims the task of "liberating populations oppressed by alien tyranny." In other words, they took up once more the historic task of Liberalism in its nationalist period, and transformed the war into an international crusade in defence of "the principle of nationality." The free nations, the nations with sovereign people and parliamentary government, the countries of the "Glorious Revolution," of the Declaration of Independence, of the Rights of Man, and of Garibaldi and Mazzini, have sprung from the defensive to advance the banners of Liberty and Democracy, to free "all peoples, small and great" who groan under the yoke of emperors and militarists.

And "beyond everything" they seek "such a settlement as will secure the happiness and contentment of the peoples." The spirits of Cromwell, of Washington, of the heroes of the French Revolution, of the "'48," and of the Liberation of Italy are conjured up to march in the Allies’ War for the emancipation of the world.

The Governments of the Allies have represented the war in this light in order to enlist the democratic sympathies of their peoples who, being politically free, have had to be convinced that they are fighting for national integrity and honour and, also, for the universal application of their ideals. It has been the easier to do this because Germany and Austria-Hungary have never been liberalised, and still remain under the reactionary political forms which Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, the United States, and, now, Russia have thrown off. The capitalist class in these countries has, therefore, been able to pursue its present-day ambitions under the banner of a war for Liberty and Democracy, the causes which it championed at home in the days when it was struggling for political power against the Crown and the landed nobility. Liberalism is the creed of the capitalist class. When this class was endeavouring to gain political power from the old-established landed class and the Crown, it practised Liberalism at home. Now that the capitalist class rules in every allied nation, and has all the social and political power that it can obtain, and is, moreover, menaced by the rise of the Socialist working class, it practises Liberalism away from home.

In Germany, the Government, as Liebknecht said in his court-martial statement:

according to its social and historical status, is an instrument for oppression and exploitation of the masses of the working population; it serves solely, both at home and abroad, the interests of Junkerdom, of Capitalism, and of Imperialism.

Therefore, the German Government represents the war as a struggle for the Freedom of the Seas, and for the integrity of the German Fatherland—the latter being the cause which originally rallied the German Radicals, and still holds the enthusiasm of the Socialists.

In Germany the capitalists, as a class, are allied with the Kaiser and with the Junkers, because these are less obnoxious to them than is "the enemy at home," the Socialist working class which, but for the army, would very soon be able to overthrow not only Kaiserdom and Junkerdom, but German Capitalism as well. The Socialist working class grows in numbers and in antagonism to the monarchist-militarist-aristocratic-capitalist bureaucracy, but at present it believes that it must guard the German Fatherland and the future national life of the German people against the armed forces of enemy capitalist governments desirous of dismembering Germany and stopping her industrial and social progress. The German Social Democracy does not believe that Lloyd-George and Milner, President Poincaré and Premier Clemenceau, Baron Sonino and President Wilson are prosecuting this war to overthrow the German ruling classes, and to establish a Social Republic on the ruins of Kaiserism. It does not think that the fine principles enunciated by Mr. Asquith at Dublin on September 25, 1914:—

Room must be found and kept for the independent existence and free development of the smaller nationalities—each with a corporate consciousness of its own—

have been vindicated in Dublin or in Ireland generally, in Egypt, in India, in Morocco, in Greece, in Albania, in China, or in Mexico. It does not think that American Capitalism has held out much hope of "making the world safe for democracy" at Butte, in Boston, or in the United States Post Office. German Social Democracy has heard from Petrograd and from Paris about secret treaties that do not seem to its mind to bear out that the Allied Governments are aiming at

the re-organisation of Europe, guaranteed by a stable régime and based at once on respect for nationalities and on the right to full security and liberty of economic development possessed by all peoples, small and great.—(Allied Note to President Wilson. Paris, January 10, 1917.)

II.

GERMANY’S MARCH TO THE EAST.

In Der Drang nach Oesten, considering the war aims of the Central Powers, it is sufficient to speak of those of Germany, because she almost completely dominates her Allies, politically as well as economically. Austria-Hungary, in so far as its natural resources have been developed and it has become industrialised, has come to depend on German capital and to be the economic feudatory of the great financial interests of that country. Bulgaria is politically and economically insignificant and Turkey, unable to maintain her independence in a world whose social and political development has left her behind, has committed herself to the exploitation and control of Germany.

Weakness in sea-power, as well as geographic disabilities for the development of over-seas commerce, caused Germany to seek outlet for her capital, as well as her trade in other directions. France neither required nor desired her assistance and, in consequence, she turned east and south. In doing this she was materially helped by the technical improvement of overland transport, by the railway and the automobile, which have permitted of the industrial development of regions remote from navigable rivers and seas. Under these conditions, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the Balkans, Asia Minor, and Central Asia have offered themselves as the natural markets for German goods and have, for the very reason above stated, only just become available for exploitation. They are, virtually, virgin lands, and are of enormous expanse and limitless wealth.

Germany has, since 1870, become a great capitalist country and, more particularly, in the last twenty years has experienced the increasing difficulty, common to all lands where capitalism has prevailed for some time, of marketing her surplus production. German capitalists have become more and more perplexed by the problem of maintaining the rate of interest on their growing accumulations of capital. They have not failed to realise that, whilst trade may be welcomed, foreign capital is not so gladly accepted in the territories of other nations, and that, as competition becomes more and more intense, the capitalists who control the governments of other countries will use their political power to defend their own interests and injure those of their rivals.

Foreign capital has not been welcomed even in the British Empire to construct and exploit railways and great public works, and it has all along been obvious that, as competition became more acute, steps would be taken to keep British markets for British capital. The German Government, "the executive committee of the junkers and the capitalists," has, therefore, helped to build a bridge for German capital across Austria-Hungary and the Balkans to Asia Minor and the East. If it could not only build that bridge, but fortify it by alliances and military might all the way from Bremen to Bagdad, it could secure not merely the exploitation of the countries along the route, but of Russia and Central Asia, as well for its own capitalists. Then, by railways, trans- continental roads traversed by fleets of motor-wagons, ship and barge canals, river development, utilisation of water-power, etc., the German capitalist class could drain the wealth and organise the man-power of these lands.

Such was the prospect that technical progress in manufacture, transport and power development presented to Germany if she chose—as she did choose—to take it. She chose it because the greater German industries are engaged in the production, not of textiles and articles of common consumption, but of iron, steel, machinery, etc., means of transport and of production and reproduction, articles which are slow to waste and, therefore, slow to sell—which is the greatest of all faults when production is organised not for use but for profit.

Germany's production and export of iron and steel have, in recent years, been enormously expanded. Her output of pig iron rose from 4,584,882 tons in 1890 to 17,586,521 tons in 1912. Her exports of steel rails rose by about 400 per cent between 1897 and 1910. The outlook for the future was becoming the more important, because the American production of iron and steel was going ahead far more rapidly. Whilst to-day Germany and Austria-Hungary produce 21,000,000 tons of steel, the United States maker more than 41,000,000 tons.

Washington is seeking "to familiarise the American newspaper reading public with the situation in the Balkans, and to impress upon American minds the fact that the peace of Europe, and of the world, depended upon preserving the integrity of the Balkan nations." (The World’s Work, New York, August, 1917.) The paper heads the article, "The Safety of America lies in the Balkans."

III.

THE PASSING OF THE TURK.

The Turkish Empire, no longer able to stand alone, and mortgaged to the hilt to the European bond-holders, with its resources ear-marked, and its future development become the booty for which the investors and contractors of Europe and America wrangle and struggle, is now the battle-ground of rival crusaders. The Germans extend to it their "protection," and fight for its "independence and integrity," meanwhile they proceed to exploit it in its entirety. The Allies have come to liberate its populations, oppressed by alien tyranny, and to save them from Turkish misrule and from German exploitation. Britain, France, and Italy will become sponsors for the "happiness and contentment" of its peoples, and will extend their benevolent protection and generous credit to develop the latent resources of the country, to reclaim it from the wilderness, and to make it safe for democracy. They propose, according to the secret treaties discovered by the Revolutionaries in the Foreign Office at Petrograd, to divide it into spheres ofinfluence and protectorates.

Britain, it is alleged, is to take over Mesopotamia and to extend her suzerainty over a federation of "free" native States m the Arabian Peninsula. France is to have Syria. Italy is to be given Cilicia and, possibly, Smyrna and the hinterland. Russia may take Armenia, and was, originally, promised Constantinople and, presumably, the shores of the Straits.

Mr. Brailsford has said that the promoters of the Bagdad Railway "secured from the first a monopoly over the rich oil wells of Mesopotamia, and they reckoned that their undertaking would serve as a basis fora future claim … that the whole region served by the Bagdad Railway is a German economic sphere. If this were to include the irrigation of Mesopotamia, it would be probably the most valuable privilege still open in any undeveloped country."[1] It is the Deutsche Bank which stands behind the Bagdad Railway scheme. (German Great Banks, Riesser, U.S. Monetary Commission, p. 474).

Lord Desborough tells us that Mesopotamia could grow corn to feed the whole of the world. Its soil, if properly irrigated, would yield enormous crops of cotton. Thus three of the most valuable commodities known to modern commerce can be obtained by whichever group of capitalists can secure the exploitation or development of Mesopotamia and the adjoining British zone of Persia, the pipe lines from whose petroleum wells drain to storage tanks at the head of the Persian Gulf. There is petroleum for motor and marine transport, and for industrial power; cotton for the mills of Lancashire, and corn for the wheat-pits of the world’s corn exchanges.

But before any of this wealth can be produced or marketed, vast irrigation works, railways, canals, harbours, grain elevators, silos, cotton warehouses, etc., must be constructed, and mining machinery and pipe-lines installed. There is work for the Pearsons, Sir John Jackson, Fraser and Chalmers, Portland Cement, Arrols, Stewart and Lloyds, Stone and Webster (of Boston), or the German master-builders in ferro-concrete, structural steel, tubes, and mining machinery.

As for cotton, the United States "has almost a monopoly in cotton raising," with two-thirds of the world-production. (Annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science, May, 1915.)

Now that the United States is taking stock of its resources, and preparing to make use of its "industrial opportunity,"" the cotton users of Lancashire, the British Cotton Growers' Association, and all those who make cotton goods for profit, and not for use, have increasing incentive to add to the cotton-growing territories under the British Flag. Once Lancashire textile capitalism experiences the difficulties of Sheffield and Glasgow steel capitalism in securing raw materials and holding its own in the world's markets, its politics must respond to its pocket. Mesopotamia's capacity to produce abundant cotton for the future is the price offered to Lancashire for support of the Paris proposals. Cheap corn and cheap fuel are similar inducements offered to those who produce for the export trade, and whose opposition to tariffs on machinery, dyes and foodstuffs would be quite natural now as in its past.

Syria, which France desires, is one of the richest and most promising provinces of the Turkish Empire. France has immense and long-established financial claims on Turkey, which will certainly make her content with no mean share of the compensation of the onerous tasks of the long campaign. At the time of the Balkan Wars she had 80 per cent. of the foreign credit capital of Turkey, and her bond-holders had then 55 per cent. of the Imperial Ottoman Debt.

In April, 1914, Franco-Turkish agreements were signed for a loan of 800,000,000 francs in exchange for railway and port concessions. These interests are all threatened by Germany and, doubtless, "France" will desire to fight to the last poilu for honour and the security of her investments. It has been both for La Patrie et le pouche that the entwined banners of Britain and France have been set on the corpse-strewn shores of Gallipoli, amid the malarial swamps of Saloniki, and advanced to free the lands of the Cross from the shadow of the Crescent. It has been for railway contractors and bond-holders, for petroleum syndicates and wheat gamblers, for mining speculators and land-grabbers, for the profiteers of London and Berlin, of Rome and Vienna, of Paris and Cologne, that the tragedy of the Dardanelles, the horror of Mesopotamia, the massacres of Armenia, and the agony of Serbia, have been endured by the exploited repositories of labour-power, which is all that the workers of Europe and Asia are to the capitalist class and the capitalist governments of every land.

IV.

IMPERIAL ITALY.

Italy went to war to restore to the bosom of the Motherland the territories of Italia Irridenta, Trieste, and the Trentino. It was to this crusade for the completion of the historic task of Italian unity, and the liberation of her children groaning under the alien tyranny of Austria, that she called her heroes when she unsheathed the sword of Freedom and Democracy. This was the sacred duty which rallied all the forces of Italian Liberalism, and sent a wave of sympathy through the breasts of those who, in many lands, thrilled to the memory of Garibaldi.

Italy rose and stood side by side with her old ally, France, taking up the hallowed flag of National Liberty. But, if the Italian populace roared themselves hoarse for the recovery of their oppressed countrymen, the Italian capitalists thought more of that Sacred Egoism—the Italian phrase for what the Germans call "liberty of national evolution"—which called them to participate in the permanent settlement of Balkan politics, and to "contribute to the Balkan revival, just as in the Middle Ages, when, together with cargoes of manufactured goods, Italian ideas penetrated into Serbia, and Italy served as a channel of spiritual communication between the Balkans and the rest of Western Europe." (Italy and the Jugo-Slav Peoples, by Civis Italicus.)

Italian capitalism has been in the main under the domination of German finance and technique, but there has been a widening stream of British and French capital flowing into certain industries, more particularly in response to the desire of the Italian Government, under the increasing control of a native capitalist class, to emancipate itself from political dependence on Germany, and to achieve an equilibrium of foreign economic interests.

The desire has, all the time, been present among Italian capitalists to throw off the yoke of German control, but they have needed to proceed with extreme caution, because of their own weakness. They have not desired to drive out Satan by inviting in Beelzebub, or to emancipate themselves from Frankfort and Berlin in order to commit themselves to London and Paris.

They have been handicapped by the natural weakness of industrialism in a country which has very small reserves of iron and no coal. Because of their weakness they have needed to follow a tortuous and vacillating policy, which often has had the superficial appearance of selfishness and dishonesty. Capitalist competition is not always the best teacher of international morality.

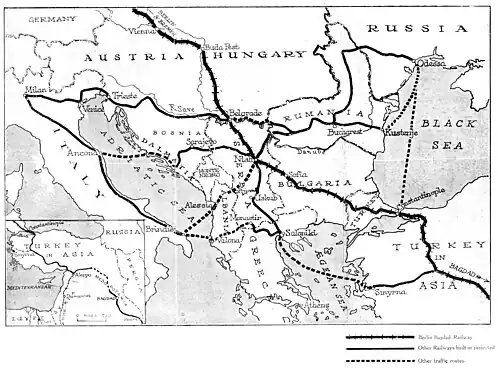

The Italian industrialists in the iron, steel, and engineering trades, and the financiers, have known that if they could tap the latent mineral wealth which lies in the Balkans, and deflect a considerable volume of commerce from the Belgrade-Uskub-Saloniki route to a Belgrade-Sarajevo-Dalmatian, a Saloniki-Monastir-Durazzo, a Monastir-Valona, or an Alessio-Scutari-Prizren-Uskub-Nisch-Rumanian route,[2] they would, at once, obtain a great increase of mineral raw materials and a large trade and traffic revenue, which would enable them to build up national capitalist economy independent of

THE RAILROADS OF THE BALKANS.

Germany on the one hand and Britain and France on the other.

For years, Serbia and Montenegro were compelled to look to Austria-Hungary for a market for their cereals and cattle; there to be met by the tariffs imposed by their Hungarian competitors. Serbia could not find an outlet for its commodities, except by the consent of Austria-Hungary, so that a port on the Adriatic became for her a "matter of urgent necessity."

Thus, about ten years ago, Italy began to take an interest in the scheme of a railway which would ensure that "she would thus have at a short distance from her coasts the means of raising the fortunes of her great Adriatic ports, and, through Venice, the great Lombard emporium, would find an important and near market in such conditions as to be able to compete with Austro-German commerce, which now overflows (floods) those markets with the lines from Vienna, Belgrade, and Nisch, and which will monopolise still more those regions with the Sarajevo-Mitrovitza-Uskub line, if no one arises to compete with it upon the same field."

The Italian Foreign Minister, Tittoni, interested himself in the project which the Serbian Government was planning "with the Imperial Ottoman Bank for the formation of a company to construct and run the railway, and the port, without which the line could not subsist."

A group of Italian capitalists, through the Banca d'Italia, entered into negotiations with the Ottoman Bank (which was dominated by French capital). A company was formed under the patronage of the Serbian and Italian Governments, in which the capital was to be drawn from France, Italy, Serbia, and Russia. This was announced in June, 1908.

Austria-Hungary immediately afterwards announced the annexation of the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which she occupied and administered under the Treaty of Berlin, 1879.

Signor Tittoni, in a subsequent speech in 1908, defined what he professed was Italy's attitude towards Balkan politics thus:—

It is, therefore, a complete work of reconstruction which is wanted in the Balkans; we ever had a clear vision of this necessity, and it is not our fault if our disinterested advice was neglected. … When the Balkan States will form a compact force which will oppose valid resistance against whoever shall make an attempt upon their unity, all covetousness will cease. … Our action of peace, of progress, of union with the Balkan States is in conformity with that of the other Powers. Among these there is one to whom an ancient tradition has assigned this task; I am speaking of Russia. I have endeavoured to render more intimate our relations with Russia also when there existed in Italy currents of opinion which were opposed to it. … The rapprochement between Italy and Russia, to which M. Isvolsky and I have turned our efforts, is to-day an accomplished fact, which will not fail to have important consequences in the future. (Italy's Foreign and Colonial Policy. Selected speeches of Signor T. Tittoni, pp. 137–138.)

Before acquiescing in Austria-Hungary’s action, he insisted on her guaranteeing that, notwithstanding her annexation of the Bosnian coast, she should maintain the freedom of the Montenegrin waters. In addition Italy took other steps, more or less peaceful in effect. She came to an understanding with the other Powers

more directly interested in the matter to assure the prompt execution of the Adriatic-Danubian Railway, from which Serbia and Montenegro expect their economic independence,

and from which the Elba-Terni-Orlando-Odero-Vickers, and the Armstrong-Pozzuoli-Ansaldo interests anticipated very substantial contracts for railway material, they having recently completed the work entailed in the overhauling of the State railways. She came to an agreement with Russia when her King and the Czar met at Racconigi in 1909, and in March of the same year she voted a new naval programme of 200,000,000 francs, her first Dreadnought being laid down almost simultaneously with the first Russian Dreadnought. The naval armament orders of both nations were sub-let to British firms as the premier naval constructors of the world.

Italy and Austria-Hungary managed to keep the peace during the Balkan Wars, and even during the setting up of the German "Kingdom of Albania." But Italy's mind was made up. As Baron Sonino told the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister, when they were discussing the question of Albania in 1915, her one concern was to prevent any third person from going there. Italy had chosen to regard the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia as a breach of the Triple Alliance, and remained neutral, only asking for "compensations" for doing so. These were rather extensive. She demanded Trieste, the Trentino, twenty islands off the coast of Dalmatia, and recognition of the complete sovereignty of Italy over Valona and its bay, including Sasseno, together with all the territory in the hinterland necessary for their defence.

Valona was the capital of Albania, which Italy had found it necessary to occupy in the winter of 1914–15, "because of the alarming state of anarchy there." When she had done so, she had informed Austria "that, in fact, that country had no sort of attraction for her."

Generous-hearted Italy was doing her simple duty, repressing anarchy, liberating oppressed nationalities, and securing their "integrity and independence," their "happiness and contentment."

Baron Sonino declared, December 1, 1915, that:—

the political and economic independence of Serbia is the corner-stone of Italian policy in the Balkans. … The political and economic subjection of Serbia by Austria-Hungary would be tantamount to a grave and constant peril for Italy. It would be the construction of an inseparable barrier to our economic expansion on the opposite shores of the Adriatic.

Yet Sir Arthur Evans stated in the Manchester Guardian, May 13, 1915 (and has not been refuted) that Italy demanded from the Allies, as the price of her intervention, Northern Dalmatia, from the coast to the mountains, together with Fiume. Russia was only made to enforce these views on the Serbs–who regarded them as inconsistent with their economic independence–"under protest from the most exalted quarters, and under extreme pressure exerted in an extraordinary manner on the part of its Western Allies."

On June 3, 1917, Italy established a protectorate in Albania, guaranteeing the unity and independence of all Albania under the ægis and protection of the Kingdom of Italy.

Such is the manner in which Italy has discharged her part of the war for Liberty up to date, occupying and protecting lands which have no attraction for her, in order that Right may triumph over Might, and that the little peoples may enjoy the blessings of Italian commerce and culture.

But she will find compensations.

These countries are of a considerable potential wealth, but little exploited; they lack railways, roads, great public works, and, above all, industries; nor will they for many years to come be in a position to provide for their own needs. Up till now they have imported the greater part of their industrial products from Austria-Hungary, from Germany and from Great Britain, while Italy has occupied a relatively modest position in this field. In the future, however, thanks to the hatred excited by this war against Germany and Austria, the Balkan States will certainly do their best to find elsewhere the products of which they have need … the field will remain open above all to Great Britain, France, and Italy. The latter, in view of her excellent geographical position with the ports of Brindisi, Bari, Ancona, Venice, and, let us hope, also some of those on the other shore, ought to be in a position to enjoy a large share of these advantages. On the other hand, we shall be able to derive from Jugoslavia many raw materials of which we have need, and contribute to the construction of public works in that region through our engineers and skilled workmen and in part through our capital.—(Italy and the Jugo-Slav Peoples—Council for the Study of International Relations.)

V.

"THE CRUX OF THE WHOLE STRUGGLE."

We shall now examine the Alsace-Lorraine question as an economic problem affecting both France and Germany. We shall then get the key to the immeasurable misery and bloody carnage of the German assault on Verdun, the invasion of Belgium, and the siege of Antwerp. We shall see that this has, indeed, been a war of blood and iron.

The Allies are determined, and France is implacably resolved, to recover the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, torn from her body in 1871. The German Chancellor accuses France of seeking, by secret engagement with the ex-Czar, to extend the French annexations to the left bank of the Rhine. Ex-Premier Ribot admitted that his government was in favour of setting up this province as an autonomous buffer State, having preferential trade relations with France.

The German Government, on the other hand, will not clearly define its attitude towards annexations, and the Berliner Tageblatt, especially, blames the coal and iron masters and kindred interests for this hesitation on the part of the Chancellor to renounce annexations.

La Nation, of Basle (Swiss Independent), June 9–22, "suggests that the war is now mainly due to the very vital conflict of economic interests in connection with the iron resources of France and Germany."

According to the Kölnische Zeitung, July 5, 1917 (National Liberal and Industrial Capitalist organ), the report of the Finance Committee of the French Chamber says:—

Our dear provinces of Alsace and Lorraine hide endless treasures in their soil. Besides their mines of coal, iron ore, salt, and phosphates, we shall find huge deposits of saltpetre, whose fabulous worth probably reaches 10 milliards. We must also mention the asphalte deposits and the petroleum wells.

The Bulletin of the Federation of British Industries, October 2, 1917, asserts:—

If Germany loses the Lorraine ores and the Basin of Briey she will never be able to go to war again. In reality, the iron-ore beds of French Lorraine are the crux of the whole struggle.

As early as May 20, 1915, the League of Agrarians, the League of German Peasants, the Westphalilian Group. of the Christian Associations of German Peasants, the Central Union of German Manufacturers, the League of Manufacturers, and the Union of the Middle Classes of the Empire, all capitalist or "tame" Labour Associations, issued a memorandum demanding the continuance of the war no matter what the sacrifices, in order that the country might emerge victorious with added power abroad, and the guarantee of durable peace.

In this document they stated:—

… we demand on the one hand the annexation of territories for agricultural colonisation, and on the other hand the mining area of Meurthe-et-Moselle, as well as the French coal areas in the department of the North and the Pas du Calais, besides the Belgian areas.

This memorandum speaks so truly and so nakedly the Real-Politik of Capitalism that we quote from it at length:—

… if the production of cast-iron and steel had not been doubled since last August (1914) it would have been impossible to continue the war. Oolithic iron ore, the primary element for the manufacture of iron and steel, is assuming increasing importance, for only this mineral is being found in Germany in increasing quantity. The production of the other home areas (apart from Lorraine) is extremely limited, and importation from overseas, even from Sweden, is rendered so difficult that in many districts, even apart from Luxemburg and Lorraine, oolithie iron ore represents 60 per cent. or 80 per cent. of the production of pig iron or steel. It should be noticed at the same time that the high proportion of steel extracted from oolithic iron ore offers the only possibility of supplying German agriculture with the necessary phosphoric acid when the importation of phosphates is stopped. Therefore, the security of the German Empire in a future war demands the possession of all the deposits of oolithic iron ore, including the fortresses of Longwy and Verdun, without which these deposits could not be defended. … From to-day, as is shown by the embargo on coal by England, this material is one of the decisive factors of political influence. Industrial neutral States are forced to make themselves the instruments of that belligerent party which can assure them their supply of coal. At present we are not in a position to do this to the extent required, and from to-day we are forced to have recourse to the production of Belgium, so as not to let our neutral neighbours become completely dependent on England. … The fact that coal, which gives coke or gas, contains at the same time the essential elements of our principal explosives is doubtless known to all. … If our hostile neighbours secure the sources of mineral oil, Germany must take care to secure the necessary supplies of coal. …

In 1871, Bismarck insisted on taking over the iron deposits[3] north-west of Metz in exchange for an extension of the defensive boundary of the fortress of Belfort. (Lectures pour Tous, 15/8/16.)

The Journal of the Iron and Steel Institute (1871, Vol. II., p. 110) remarked:—

The consequences of the cession of Alsace and Lorraine to the German Empire will be to diminish the iron-producing capacities of France about one-third of what they have hitherto been, since of the entire eastern iron district the Longwy basin alone is all that remained to France. … About three-fourths of the iron production of the old French department of the Moselle will now be diverted to the Zollverein, the new boundary-line places in the latter country, with the exception of the Longwy group of iron mines, all the rich deposits of oolithic ironstone in the Moselle and the Meurthe.

according to an article by a great French mining engineer in the Engineering and Mining Journal (New York), 19/6/1909:—

When the new boundary between France and Germany was marked on the ground, the German representatives were accompanied by the chief engineer of mines of their Government, with a view of getting most of the mines known at that time.

By kind permission of the Editor of the "Plebs Magazine."

The coal fields of the Saar are shown; the iron fields of Longwy and Briey, situated just where the frontiers of Belgium, Luxembourg, France, and Germany meet; and the iron fields of Meurthe-et-Moselle, lying but a few miles within the French border. Only a few of the principal works and mines are indicated, anything like a complete map being, of course, impossible on this small scale.

J.F.H.

Since 1871 the development of the iron mines has been considerable, particularly since the invention of the Thomas basic converter process in 1880, which made possible the treatment of the phosphoric ores known in Lorraine as minettes. The discovery of the deep levels of the Briey district has given a new impulse to the output, which in 1906 was about 27,000,000 tons. The relative importance of this deposit in the three leading countries is shown by the following statement of their reserves:—

Luxemburg, 300,000,000 tons from an area of 3,600 hectares; Germany, 1,100,000,000 tons from an area of 48,000 hectares; France, 2,500,000,000 tons from an area of 43,186 hectares.

M. Bailly, engineer to the French Government, estimated, about 1908–9, that the Luxemburg reserves would be exhausted by 1945, the German reserves by 1953, but that the French output would not reach its maximum for another twenty years, and that the deposits would not be worked out until 2023.

Krupp and the Gelsenkirchen Co., Thyssen and Stinnes, the great coal and iron-masters, the "Phœnix,’’ and the Guttehofnungshütte are among the world-powerful German steel interests having establishments within a few miles of the Franco-German frontier. Schneider-Creusôt, the Chatillon-Commentry Co., and the St. Chamond Co., the three greatest armament firms of France, derive almost the whole of their native supplies of iron-ore from this region, and there can be no doubt that fears for the exposed position of this region, as well as German economic aggressiveness in this area between 1900 and 1905, largely determined their attitude towards the Morocco policy of their Government. It is well known that Schneider played a most prominent part in the Morocco question, and all their French mines are in territory now in German occupation.

So long as the national defences of France depend, in the event of war, upon over-seas supplies of iron and coal, her diplomacy will work at a disadvantage. Such a condition of affairs will not be agreeable to the French capitalists, and for them Alsace-Lorraine has become more than a question of honour. It has become one of overwhelming economic and political importance.

France only produces two-thirds of the coal that she uses, and before she could begin to develop the iron reserves of Normandy and Brittany she had to obtain coal from abroad. At first Thyssen became largely interested in the Mines de Joumont, and took away the ore into Germany, the French owners importing fuel from Thyssen's collieries in Westphalia, in which they became shareholders to an equal extent. French patriotism intervened to buy out German capital from the sacred soil of France and to look for coal from other quarters.

If France annexes Alsace-Lorraine her total deficiency of national fuel supplies will be relatively increased. At the same time, she will be annexing iron mines, which will be worked out in a little more than a generation, although in seizing Metz she will make Briey impregnable.

The Iron Trades Review (Cleveland, Ohio, 26/4/17, says:—

The annexation of the Saar basin would modify this condition somewhat by adding 13,000,000 tons to the annual production of coal. About 9,000,000 tons of this would be absorbed by the region itself. The remainder, although it would not wipe out the need for coal in France, would be quite useful for supplying the railroads and small industries. However, the Saar basin, in addition to its coal deposits, brings with it several steel plants. With Lorraine it would practically double the (steel) production of France.

That largely explains why French capitalism wishes to restore the old Rhine frontier of the Republic. The coveted fuel supplies lie beyond Alsace-Lorraine.

But as there has grown up more particularly in the last few years a great traffic between English and Welsh ports on the one hand, and French ports on the other, exchanging British coal and coal briquettes for French iron-stone, and as this has come to be of very considerable importance to the industry and commerce of Cardiff, Newport, and Swansea, there is no reason to doubt that

in regard to Alsace, the Government (British) had never heard, and had never approved, the suggestion that part of Germany on the left bank of the Rhine should be cut off and made a new buffer State between France and Germany. That never was the policy of the Government. … (Mr. Balfour. Debate on War Aims. House of Commons. Glasgow Herald, December 12, 1917.)

British iron and steel interests, those interests which were primarily responsible for the formation of the Federation of British Industries and the chartering of the British Trade Corporation, which are very powerfully represented in the councils of our nation and in its press, and which have, latterly, become the dominant elements in British capitalism, view with the utmost seriousness the problem of securing iron-stone supplies for their blast furnaces in adequate volume and at reasonable costs of production and transit. They have under consideration the most drastic projects for reorganising the colliery, iron and steel, engineering, coal by-product recovery, electrical power raising, distribution and usage, lighting, heating, tramway and motor transport undertakings of this country so as to economise to the utmost costs of materials, of labour, of management, to centralise control, and to increase efficiency and profits. This vast programme of reconstruction, including the very carefully concealed plot for relieving the municipalities of their self-supporting electrical undertakings and vesting these in a series of gigantic boards of "control" is being contrived by an alliance of colliery-owners, iron and steel magnates, and electrical plant makers who are "conserving" energy, developing our mineral reserves (petrolliferous, ferrous and non-ferrous) and compassing the world for markets for their coal output in exchange for foreign iron-stone. They are discussing this Alsace-Lorraine problem unceasingly and, whilst they want France to recover Lorraine, they do not desire to dismember Germany or to put the German population of the Saar coalfield under an alien flag. They believe in the ideals for which the Allies are fighting all the more enthusiastically because the task "of liberating populations oppressed by alien tyranny" does in this case conform exactly to their interests.

Meanwhile, the restoration of Lorraine to the bosom of La Belle France, would increase the French iron-ore output from 21,700,000 to 42,000,000 tons a year, and reduce the German output from 27,000,000 tons to 7,000,000 tons. France would thereby destroy not only the material basis of Prussian Militarism, but the very basis of German industrial power. Moreover, she would render herself much more independent of German coal supplies by forcing Germany to barter cheap fuel for dear iron. "Germany would depend absolutely on France for iron-ore."

On the other hand, the German capitalists desire to rob France of the whole of her Lorraine iron deposits; to reduce the total of her native reserves from 4,000,000,000 to 1,500,000,000 tons; to get rid of the need of exporting coal to France, and so to free greater tonnage for general export purposes; to annex or, at any rate, secure the first claim on the coal production of Belgium and Northern France, and to make Antwerp, which has grown wealthy out of transit traffic in and out of Germany, and which is the seaport of the Meurthe and Moselle iron-field, a part of Germany's trade system.

The French and German capitalist classes are battling to eliminate each other; to become independent of each other; to become supreme in the exploitation of the richest accessible mineral reserves in the world. They are contending for the raw materials of industry and the gains of commerce. They are not fighting so much for national honour and integrity, as for national economic ascendancy. The victor will not be content with his conquests, for capitalism must always reach out unto new markets, new fields of investments for new profits on new "fruits of abstinence."

The mystery of "annexations" and "the rectification of frontiers" is explained. It is not "Deutschland über Alles," nor "Tout pour la Patrie," but "Capitalism over All," and "Everything for Pocket."

VI.

"THINKING INTERNATIONALLY."

The United States of America is in quite a different category as to war aims from the nations with which it is more or less completely allied. It came into the war ostensibly to maintain the freedom of ocean traffic, to champion the cause of the neutral carriers, to vindicate international law, in fact, with a view of "making the world safe for democracy." It came in to uphold the right of a neutral nation to carry on mercantile intercourse with a belligerent Power without running the risk of having the property and lives of its citizens jeopardised in the way that they were being jeopardised by the German submarines.

Now that America is in the war, she means to enforce the inviolable sanction of the pledged word, to overthrow personal government, and to exert her influence to the uttermost for the "open door" in trade, and a liberal political settlement for all the nations.

President Wilson has declared:—

There is not a single selfish element, so far as I can see, in the cause we are fighting for.

Secretary Lansing has answered the Pope:—

We seek no material advantage of any kind.

There is no doubt that the United States has no territorial ambitions. She has come in to enforce no trade discriminations, and she is not filled with a lust for empire and political domination. She desires to enthrone everywhere the traditional liberties of capitalist society, the ideas and the politics of the Land of the Almighty Dollar. Her altruism reflects an exalted self-interest, a refined and Sacred Egoism, revealed to some of her governing minds.

The Secretary of the Interior, for instance, informed a conference of business men that:—

We are fighting for our own interests.—(Automobile, May 31, 1917.)

The European War was America's opportunity. A continuous run of prosperity for years had made American industry relatively less indebted to European capitalists. She was preparing to become a nation of investors, and of world-developers. Still, in 1914, between £800,000,000 and £1,000,000,000 of stocks and bonds were held in Europe. The war came and

after it had been under way for a few months it was apparent that the needs of England, France, and Russia were far in excess of the manufacturing facilities of those countries—(World's Work, New York, January, 1917, p. 401.)

Orders poured into New York from Europe, with the result that the trade balance in favour of the United States rose from $851,000,000 for 1914–15 to $3,095,000,000 for 1916–17. Up to the end of April, 1917, Britain had returned £500,000,000 of mortgages on the United States. In addition, the United States capitalists, up to the end of 1916, had purchased £400,000,000 of mortgages on European property. The longer the war has gone on, the more immense have been the purchases and borrowings of the Allies. In May, the Secretary of the Treasury estimated:–

If the war continues another year it is likely that within that period a total of $9,000,000,000 will have to be expended by the Allied Governments and the Government of the United States in our own markets.–(Commercial and Financial Chronicle, June 2, 1917.)

The Allies have sold the mortgages of their subjects, they have pawned their resources and mortgaged their credit, and they have purchased colossal stocks at costs yielding high profits. When, according to Secretary Baker:–

every resource of the Allies was near exhaustion, the United States entered the war.

Immense sums have been raised at interest for the Liberty Loan, and titanic contracts have been placed at "reasonable" profits.

Says the Secretary of the Treasury:–

The transaction will resolve itself largely into a shifting of credits. The money will not be taken out of the country nor withdrawn from the avenues of business; on the contrary, it is kept in the country and circulated and re-circulated in the channels of business, with corresponding stimulation and profit to business and productive enterprise.

Interest on the loan, profits on the contracts, the security of the United States for their capital, and a political and economic influence over their debtor nations–which increases as the war goes on–that is what it means to make the world "safe for democracy"–and dollars.

The Federation of British Industries says in its official Bulletin (2/10/17):–

America and the American banker, as international factors, have now in the fullest sense arrived.

It declares that American wealth has increased 50 per cent. between 1907 and 1917, and in its issue of October 9, 1917, reports the President of the American International Corporation as saying of the European War:–

These changes are bringing the United States new responsibilities and extraordinary opportunities. … We must as a nation think internationally.

"This new slogan for the United States industries," says the Bulletin, "was thus started 18 months before the big Republic actually entered the European War. It has now been widely popularised as well as intensified by that tremendous fact."

The American International Corporation has already acquired control of the International Mercantile Marine Co., and hence of the White Star, Dominion, American, and other Liverpool steamship lines. The F.B.I. considers it to be a "potentially more powerful combination even than the pre-war German Cartels, backed and led by the German Banks." The Vice-President of this American International Corporation, founded to export capital, recently said:—

We are generously equipped, ready to begin our struggle for our place upon the ocean. … We have arrived at a crisis in our commercial history. … If we grasp it our trade will be immeasurably extended.—(International Marine Engineering April, 1917.)[4]

The President of the Steel Trust says:—

We are all satisfied that business conditions are extraordinarily good. The demand for our products is great. … The prospects in the near future and, as far as we can see, are excellent.

The continuance of the war means the building up of a great American shipping industry, a great American shipbuilding industry, a great American navy. The Government is subsidising the building of ships and forbidding the export of shipbuilding steel. The Japanese had been importing American steel and boasting that, after the war, Japan would be mistress of the Pacific and have a great Atlantic trade. President Wilson has intervened with an embargo on the export of shipbuilding steel. Japan is vigorously protesting that she is an Ally in the war for Liberty and Peace.

VII.

THE CHANGING EAST.

Siberia comes within the zone of the East, since its exploitation is destined more and more to be carried on over the railway running westward across Northern Asia from Vladivostock and Port Arthur. There are, to begin with, most extensive virgin goldfields in the Amur Valley and elsewhere in Eastern Siberia. Those on the Lena have been worked for some time, and most advantageously by a British company, but for the most part they await the capitalist and the mining engineer. Then, comments The World's Work (New York, June, 1917):—

The most readily "realisable" asset of Russia is its prodigious forests, with which it confidently expects to capture the lumber market of Europe.

Now,

American capital is familiar with the problems connected with the development of the timber industry, and American capital should therefore play a great part in the proper development of the timber industry in Russia. There is an opportunity in this connection for American timber interests, and every effort should be made to assist Russia in the development of her timber industry in order that American capital may share in the rewards. … Russia's eyes are turning to the United States. … Russia's Allies, England and France, will hardly be in a position after the war to carry on extensive financial development in Russia. This is peculiarly America's opportunity.

Almost all the uncut timber lies in Siberia, but before the gold, copper, farming possibilities and timber reserves can be operated

Russia will need 6,500 miles of railroad every year to keep pace with its developing commerce and agriculture. American capital and American engineers will find in this work a great field for service.

The Torgovo-Promyshlennaya Gazetta calculates that more than double the amount of metals that Russia's iron and steel plants can produce will be needed for this work.

The World's Work (New York, October, 1917), stated:—

We produce more steel than all the rest of the world put together.

But all this American work of service will require to be undertaken via the passages between the Japanese islands lying off the coasts of China and Siberia, where the sea-girt Empire of the East dreams of an Asiatic's mission of redemption and of civilisation, fruitful of rich compensations for Mitsui capital and Kobe and Yokohama enterprise.

Japan also considers herself the heaven-appointed guardian of the Orient, and has not been placated by American press references to her as being

nearer Germany in her political ambitions than she is to any of her Allies—(World's Work, New York, August, 1917)

to her "ambition" for world dominion; as "working vigorously for the total domination of Asia."

Japan is, also, in the Alliance against Kaiserism, and on the side of Liberty and Democracy. Like the Dollar Republic she is, by the conditions of her position and her history, somewhat of a free lance, and her Allies are rather inclined to take the view that she is not so convinced and whole-hearted a champion of Western ideas of the rights of small nationalities as they are themselves.

They do not unreservedly approve her methods of maintaining "the independence and integrity of the Chinese Empire, and the principle of equal opportunities for the commerce and industry of all nations in China," to which she committed herself by her Treaty of Alliance with Great Britain. American opinion, in particular, regards the "Japanese Monroe Doctrine for Asia" as a travesty of her own century-old formula of policy in the Western Continent. America wishes to ensure the "open door" in China for the entry of American commodities for trade and investment, and for the protection of the Republican institutions newly planted in Asiatic soil. Japan fears European or, even, American efforts at partition or protectorate.

When the Siems-Carey Construction Co., which is a branch of the American International Corporation, secured a concession to build 2,600 miles of railway in China, Japan resuscitated an obsolete or, at any rate, almost forgotten clause of a treaty between China and Russia, which completely blocked the scheme.

When the same group entered on a contract in April, 1916, for engineering a Grand Canal Waterway, the Japanese Government again stepped in to secure postponement of the scheme till she was ready to co-operate. (Bulletin, F.B.I., May 9, 1917.)

Now the time had come for the industrialisation, not piece-meal but in whole, of the most industrious quarter of the worlds inhabitants… No longer … a question of selling so many locomotives or so many tons of steel rails, a few dynamos or electrical parts, or of securing a railway or mining concession here or there in China. The immediate industrialisation of a vast empire from top to bottom was involved. … That was the vital fact before the war. … But those who deal in concrete values … realise somewhat the staggering debt which will have to be paid by industry and through industry.—(World's Work, New York, January, 1917.)

There speaks the American writer in the organ of the American cultural investor, apprising the potentialities of an awakening China; calculating in "concrete values," rather than in abstract ideals what "our American part may be"; estimating the productive capabilities "of the most industrious quarter of the world’s inhabitants," and foretelling that "huge fortunes will be made, great international industry produced, during the immediate development of China." "Has," says our champion of a world made safe for democracy, "Japan or any other nation the right to intervene between China's opportunities and the needs of the American or European workman?"

Here, you have Capital, as ever, perfectly disinterested, nobly obliging, dedicated to the cause of Humanity, of Democracy, of Liberty, of the working man. The same voice speaking, whether the hands be those of Eastern or Western, European or American, Teuton or Anglo-Saxon, speaking the same language, proclaiming everywhere its cultural mission, its evangel of "development," its gospel of good business, safe returns, and a fair margin of profit as its just reward for services rendered.

The investment agencies of Japan and the United States have estimated not merely the capacity of China to absorb capitalism's ever-increasing surplus of commodities, nor the available labour power "of the most industrious quarter of the world's inhabitants," but have taken stock of her enormous reserves of minerals, including iron and coal, copper and gold, her fertile alluvial lands, her untapped forest wealth, and her cotton-growing potentialities.

Japan has coal and copper, but very little iron. The steel producers of the Pacific Coast of the U.S.A. can import iron from Han-Yang more cheaply than they can get it from the Atlantic Coast. They have been trying to obtain great cargoes of iron from the Han-yeh-ping mines and the blast furnaces of the Han-Yang Iron Works. The Japanese Imperial Steel Works, like other Japanese plants, have had to import ores from Corea and China, and they take nearly the whole output of these Han-Yang properties. The great Muroran Steel Works in Hok-Kaido originally contracted with Vickers and Armstrong Whitworth to supply pig-iron from Europe. Now they obtain their ores from near Mukden in Manchuria. The province of Shantung has fabulous coalfields, besides iron, gold, and copper. The Han-yeh-ping ore mines are among the richest in the world. The province of Fo-Kien can yield enormous crops of cotton and sugar cane, and Mongolia produces raw cotton, wool, and hides on a gigantic scale.

Japan has a big textile industry, and does not wish to depend on United States cotton and Australasian wool. She has compelled the Chinese to hand over to her the Han-Yang properties, and the control of the provinces of Shantung, Fo-Kien, Mongolia, and Manchuria. Now, by arrangement with her Western Allies, she is to organise China's military system and her production of war material.

So proceeds in the East the expansion of capitalism's boundless empire of material exploitation and ideal emancipation.

VIII.

CAPITALISM THE ENEMY!

The explanation of the secret diplomacy, armament outlay, militarist preparation, wanton aggression, and heroic defence, which fill the bloody and costly calendar of the last twenty years of human history, and which have culminated in this world-wide shambles is, to the writer's mind, to be found in the workings of the capitalist system of production, and in the conflicting ambitions and desperate fears of the governing and possessive classes of all the belligerent nations. The war is not an event apart, a thing in itself, a sudden irruption of intangible forces, but a more intense development of the competitive struggle, waged by States essentially capitalist in their composition and outlook, by syndicates of national capitalist economies which now contend for markets with diplomacy instead of advertisement, expeditionary forces and invading hordes, instead of commercial travellers and selling agencies, with the bayonets and hand grenades of militarised workers instead of the picks and mandrils of the soldiers of profit.

The capitalists of the different countries have conquered their home markets and gone forth to exploit other lands. They have encountered each other on the world market and, gradually abandoning their attitude of laissez-faire, have become imperialists, protectionists, militarists, and sought to recruit their several state systems to obtain for them concessions for trade and investment, spheres of influence and protectorates. Capitalist-dominated states, like capitalist companies, have formed "cartels" and syndicates the more vigorously to prosecute their business, to monopolise reserves of cheap raw material, and to engage in cut-throat competition. In pursuit of cheapness and profit they have augmented their output, increased their available capital, and jostled each other on the borders of civilisation. Their very political institutions, their laws, their ideas reflect their capitalist nature. Their armaments are but the channels through which they hurl at one another the maximum output of their machine production. Their armed forces are but specialised and departmentalised sections of their wage and salary-earning proletariats, equipped with tools of destruction, and serving the automatic machines and heavy engines of frantic competition with the munitions of countless workshops. The capitalist economics are all of a piece, and their politics are but their organised will-power, modified according to the standard of their development, the clearness of their vision, and the solidarity of the various interests within their governing class.

Hence, we re-echo Liebknecht's challenge to his Junker and capitalist antagonists and judges:—

The present war is not a war for the defence of national integrity, nor for the liberation of oppressed nationalities, nor for the well-being of the masses. From the point of view of wage-earners it only means the extreme concentration and accumulation of political oppression, of economic fleecing, and military butchery of the bodies and souls of the wage-earning classes to the advantage of Capitalists and Absolutists.

And we join with this fearless adversary of Kaiserism and Capitalism in crying to the workers of every capitalist nation.

There must be only one answer from the wage-earners of all countries. A more intense struggle, an international struggle, of all workmen against the Governments of Capitalists and the ruling classes of all countries to get rid of oppression and exploitation, and to end the war by a Socialist Peace.

The Author’s address is 8, Johnson’s Court, Fleet Street, London, E.C. 4.

Printed by The National Labour Press, Ltd., 30, Blackfriars Street,

Manchester; and at London. 25362

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1918, before the cutoff of January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1943, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 81 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

- ↑ "Turkey and the Roads of the East," p.14. U.D.C., 2d.

- ↑ See Map.

- ↑ See Map of Lorraine opposite.

- ↑ Since these pronouncements, we are told, moreover, that apparently, therefore, the United States will eventually have a merchant fleet … perhaps larger than even England's. The construction of such a fleet is now a fixed national policy. We are building not only for the present, but for the future. … England … was really using our steel, our yards, and even our money—for the ships were to be paid for out of American loans—to assure her unquestioned maritime mastery at the end of the war. Friendly as are our relations with England, it is now our policy not to let a single ton which American yards are building slip out of our hands. … The chief argument in favour of wooden ships was the supposed scarcity of steel, but Washington no longer has any apprehension on this score … the 23,000,000 tons turned out by our mills in 1914 was increased to 40,000,000 tons last year. Our steel industries stand ready to furnish the shipbuilders’ steel plates in any quantity desired. ("World's Work," New York, December, 1917.)