CHAPTER V.

NEXT STAGE. WHAT TO DO WITH CONSTANTS.

In our equations we have regarded  as growing, and as a result of

as growing, and as a result of  being made to grow

being made to grow  also changed its value and grew. We usually think of

also changed its value and grew. We usually think of  as a quantity that we can vary; and, regarding the variation of

as a quantity that we can vary; and, regarding the variation of  as a sort of cause, we consider the resulting variation of

as a sort of cause, we consider the resulting variation of  as an effect. In other words, we regard the value of

as an effect. In other words, we regard the value of  as depending on that of

as depending on that of  . Both

. Both  and

and  are variables, but

are variables, but  is the one that we operate upon, and

is the one that we operate upon, and  is the “dependent variable.” In all the preceding chapter we have been trying to find out rules for the proportion which the dependent variation in

is the “dependent variable.” In all the preceding chapter we have been trying to find out rules for the proportion which the dependent variation in  bears to the variation independently made in

bears to the variation independently made in  .

.

Our next step is to find out what effect on the process of differentiating is caused by the presence of constants, that is, of numbers which don’t change when  or

or  change their values.

change their values.

Added Constants.

Let us begin with some simple case of an added constant, thus:

Let

.

.

Just as before, let us suppose  to grow to

to grow to  and

and  to grow to

to grow to  .

.

Then:

.

.

Neglecting the small quantities of higher orders, this becomes

.

.

Subtract the original  , and we have left:

, and we have left:

.

.

.

.

So the  has quite disappeared. It added nothing to the growth of

has quite disappeared. It added nothing to the growth of  , and does not enter into the differential coefficient. If we had put

, and does not enter into the differential coefficient. If we had put  , or

, or  , or any other number, instead of

, or any other number, instead of  , it would have disappeared. So if we take the letter

, it would have disappeared. So if we take the letter  , or

, or  , or

, or  to represent any constant, it will simply disappear when we differentiate.

to represent any constant, it will simply disappear when we differentiate.

If the additional constant had been of negative value, such as  or

or  , it would equally have disappeared.

, it would equally have disappeared.

Multiplied Constants.

Take as a simple experiment this case:

Let  .

.

Then on proceeding as before we get:

.

.

Then, subtracting the original  , and neglecting the last term, we have

, and neglecting the last term, we have

.

.

.

.

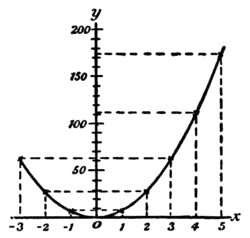

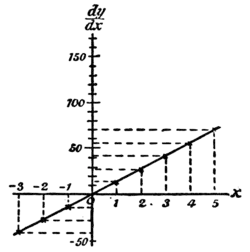

Let us illustrate this example by working out the graphs of the equations  and

and  , by assigning to

, by assigning to  a set of successive values,

a set of successive values,  etc., and finding the corresponding values of

etc., and finding the corresponding values of  and of

and of  .

.

These values we tabulate as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now plot these values to some convenient scale, and we obtain the two curves, Fig. 6 and 6a.

Carefully compare the two figures, and verify by inspection that the height of the ordinate of the derived curve, Fig. 6a, is proportional to the slope of the original curve,[1] Fig. 6, at the corresponding value of  . To the left of the origin, where the original curve slopes negatively (that is, downward from left to right) the corresponding ordinates of the derived curve are negative.

. To the left of the origin, where the original curve slopes negatively (that is, downward from left to right) the corresponding ordinates of the derived curve are negative.

Now if we look back at p. 19, we shall see that simply differentiating  gives us

gives us  . So that the differential coefficient of

. So that the differential coefficient of  is just

is just  times as big as that of

times as big as that of  . If we had taken

. If we had taken  , the differential coefficient would have come out eight times as great as that of

, the differential coefficient would have come out eight times as great as that of  . If we put

. If we put  , we shall get

, we shall get

.

.

If we had begun with  , we should have had

, we should have had  . So that any mere multiplication by a constant reappears as a mere multiplication when the thing is differentiated. And, what is true about multiplication is equally true about division: for if, in the example above, we had taken as the constant

. So that any mere multiplication by a constant reappears as a mere multiplication when the thing is differentiated. And, what is true about multiplication is equally true about division: for if, in the example above, we had taken as the constant  instead of

instead of  , we should have had the same

, we should have had the same  come out in the result after differentiation.

come out in the result after differentiation.

Some Further Examples.

The following further examples, fully worked out, will enable you to master completely the process of differentiation as applied to ordinary algebraical expressions, and enable you to work out by yourself the examples given at the end of this chapter.

(1) Differentiate  .

.

is an added constant and vanishes (see p. 26).

is an added constant and vanishes (see p. 26).

We may then write at once

,

,

or

.

.

(2) Differentiate  .

.

The term  vanishes, being an added constant; and as

vanishes, being an added constant; and as  , in the index form, is written

, in the index form, is written  , we have

, we have

,

,

or

.

.

(3) If  , find the differential coefficient of

, find the differential coefficient of  with respect to

with respect to  .

.

As a rule an expression of this kind will need a little more knowledge than we have acquired so far; it is, however, always worth while to try whether the expression can be put in a simpler form.

First we must try to bring it into the form  some expression involving

some expression involving  only.

only.

The expression may be written

.

.

Squaring, we get

,

,

which simplifies to

;

;

or

![{\displaystyle \left[(a-b)^{2}-(a^{2}-b^{2})\right]y^{2}=\left[(a^{2}-b^{2})-(a+b)^{2}\right]x^{2}}](../_assets_/eb734a37dd21ce173a46342d1cc64c92/039e38d12c61f7b5103d9636170f6c5ae2ec850d.svg) ,

,

that is

;

;

hence  and

and  .

.

(4) The volume of a cylinder of radius  and height

and height  is given by the formula

is given by the formula  . Find the rate of variation of volume with the radius when

. Find the rate of variation of volume with the radius when  in. and

in. and  in. If

in. If  , find the dimensions of the cylinder so that a change of

, find the dimensions of the cylinder so that a change of  in. in radius causes a change of

in. in radius causes a change of  cub. in. in the volume.

cub. in. in the volume.

The rate of variation of  with regard to

with regard to  is

is

.

.

If  in. and

in. and  in. this becomes

in. this becomes  . It means that a change of radius of

. It means that a change of radius of  inch will cause a change of volume of

inch will cause a change of volume of  cub. inch. This can be easily verified, for the volumes with

cub. inch. This can be easily verified, for the volumes with  and

and  are

are  cub. in. and

cub. in. and  cub. in. respectively, and

cub. in. respectively, and  .

.

Also, if

(5) The reading  of a Féry’s Radiation pyrometer is related to the Centigrade temperature

of a Féry’s Radiation pyrometer is related to the Centigrade temperature  of the observed body by the relation

of the observed body by the relation

,

,

where  is the reading corresponding to a known temperature

is the reading corresponding to a known temperature  of the observed body.

of the observed body.

Compare the sensitiveness of the pyrometer at temperatures  C.,

C.,  C.,

C.,  C., given that it read

C., given that it read  when the temperature was

when the temperature was  C.

C.

The sensitiveness is the rate of variation of the reading with the temperature, that is  . The formula may be written

. The formula may be written

,

,

and we have

.

.

When  ,

,  and

and  , we get

, we get  ,

,  and

and  respectively.

respectively.

The sensitiveness is approximately doubled from  to

to  , and becomes three-quarters as great again up to

, and becomes three-quarters as great again up to  .

.

Exercises II. (See p. 254 for Answers.)

Differentiate the following:

(1)  . .

|

(2)  . .

|

(3)  . .

|

(4)  . .

|

(5)  . .

|

(6)  . .

|

Make up some other examples for yourself, and try your hand at differentiating them.

(7) If  and

and  be the lengths of a rod of iron at the temperatures

be the lengths of a rod of iron at the temperatures  C. and

C. and  C. respectively, then

C. respectively, then  . Find the change of length of the rod per degree Centigrade.

. Find the change of length of the rod per degree Centigrade.

(8) It has been found that if  be the candle power of an incandescent electric lamp, and

be the candle power of an incandescent electric lamp, and  be the voltage,

be the voltage,  , where

, where  and

and  are constants.

are constants.

Find the rate of change of the candle power with the voltage, and calculate the change of candle power per volt at  ,

,  and

and  volts in the case of a lamp for which

volts in the case of a lamp for which  and

and  .

.

(9) The frequency  of vibration of a string of diameter

of vibration of a string of diameter  , length

, length  and specific gravity

and specific gravity  , stretched with a force

, stretched with a force  , is given by

, is given by

.

.

Find the rate of change of the frequency when  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are varied singly. (10) The greatest external pressure

are varied singly. (10) The greatest external pressure  which a tube can support without collapsing is given by

which a tube can support without collapsing is given by

,

,

where  and

and  are constants,

are constants,  is the thickness of the tube and

is the thickness of the tube and  is its diameter. (This formula assumes that

is its diameter. (This formula assumes that  is small compared to

is small compared to  .)

.)

Compare the rate at which  varies for a small change of thickness and for a small change of diameter taking place separately.

varies for a small change of thickness and for a small change of diameter taking place separately.

(11) Find, from first principles, the rate at which the following vary with respect to a change in radius:

- (a) the circumference of a circle of radius

;

;

- (b) the area of a circle of radius

;

;

- (c) the lateral area of a cone of slant dimension

;

;

- (d) the volume of a cone of radius

and height

and height  ;

;

- (e) the area of a sphere of radius

;

;

- (f) the volume of a sphere of radius

.

.

(12) The length  of an iron rod at the temperature

of an iron rod at the temperature  being given by

being given by ![{\displaystyle L=l_{t}\left[1+0.000012(T-t)\right]}](../_assets_/eb734a37dd21ce173a46342d1cc64c92/f154479602688b42397543aaac4eef5b3bde63cb.svg) , where

, where  is the length at the temperature

is the length at the temperature  , find the rate of variation of the diameter

, find the rate of variation of the diameter  of an iron tyre suitable for being shrunk on a wheel, when the temperature

of an iron tyre suitable for being shrunk on a wheel, when the temperature  varies.

varies.