Across Arctic America/Chapter 18

Chapter XVIII

An Exuberant Folk

On a fine afternoon—it was the 14th of November—just as the chill autumn sun was slipping below the horizon, I drove into the little trading station, which is built in a sheltered creek just at the mouth of Arctic Sound. And here a pleasant reception awaited me, in that I found two fellow-countrymen.

The station was in charge of Mr. H. Clarke, who was, moreover, entrusted with the organization of all the new stations east of Baillie Island. And his assistant was a Danish trapper named Rudolf Jensen, who had been working on his own account for some twenty years in the region of the Mackenzie River delta, and was now engaged in the Company's service. Even more pleased was I to find Leo Hansen, the film photographer who had come up to meet me and share our final spurt through the third and last winter of the expedition. I had written home from Repulse Bay in January, 1923, asking my Committee to send out a film photographer, as I felt convinced that motion pictures would be a valuable addition to the other material we were collecting. He had made an adventurous journey on his own account, first from Copenhagen to New York, then across Canada to Vancouver; from there on board the Hudson's Bay Company's steamer Lady Kindersley northward via Point Barrow and Herschel Island to the little trading station at Tree River, in Coronation Gulf, and thence finally to Kent Peninsula by the little schooner that plies, during the brief arctic summer, between the small outlying stations towards Victoria Land. He had brought his technical impedimenta through without mishap, and was eager to get to work.

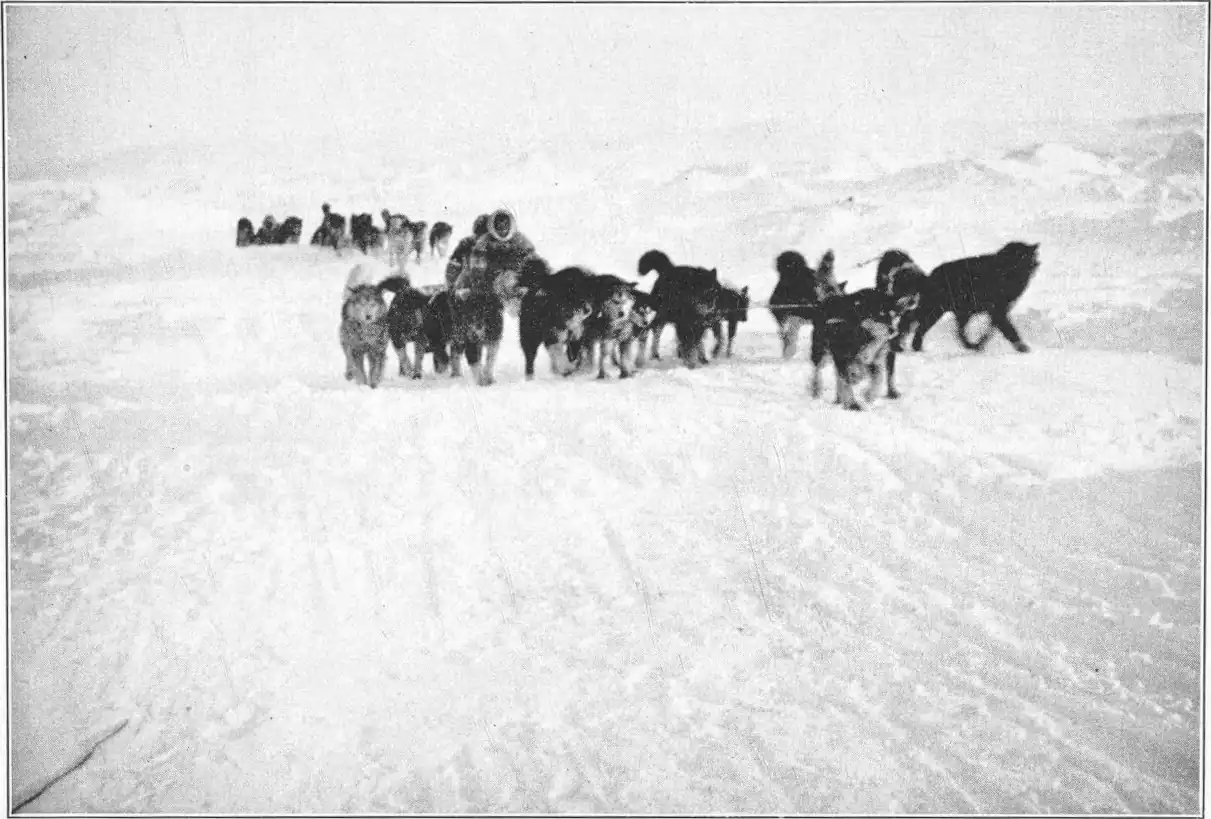

In any case, we could not afford to make any long stay here; winter and darkness were upon us, and we could not reckon on light enough for motion pictures in December. By the time it was light again in March, we should be well out of the North-west Passage country, among the semi-civilized Eskimos of the Mackenzie Delta; it was essential therefore to make the most of our time now.

The natives here are generally known as Kitdlinermiut; that is, among the other tribes to the eastward. And the use of the word, which means "frontier" or "boundary," among the tribes to the south may doubtless be taken as suggesting that the Kitdlinermiut are "the people farthest to the north." They constitute, as do the Netsilingmiut, one tribe, all the members of which are acquainted, and often meet at the various hunting grounds, but certain subdivisions are reckoned with, according to locality.

There are the Eqalugtormiut, or People of the Rich Salmon Rivers, from the neighborhood of Cambridge Bay in Victoria Land, numbering 98 souls, of which 54 are men and 44 women; the Ahiarmiut, or People

The natives of Victoria Land live mainly by caribou hunting and salmon fishing in summer and autumn. Seal hunting is carried on from the ice between Kent Peninsula and Victoria Land, sometimes extending more to the westward, linking up with the Kiluhigtormiut at Bathurst Inlet, sometimes more to the east, meeting the Netsilingmiut in the neighborhood of Lind Island. The Ahiarmiut also move up to the north-eastward in the spring.

These Ahiarmiut are undoubtedly the most nomadic of the Eskimo tribes, and thus the most skilful and hardy travellers. They will sometimes spend the summer right over in Victoria Land, at Albert Edward Bay, at other times penetrating far into the interior of the mainland, taking part in the great trading assemblies which, prior to the formation of the trading stations, were regularly held in the Akilineq hills, right up in the Barren Grounds. On these occasions they would even journey as far as the forest belt, to procure timber for kayaks and sledges. They are regarded as not only the most skilful, but also the most warlike of the tribes. And their numbers, 70 men against 46 women, also suggest that the reputation is not undeserved, since there are as a matter of fact, more girl children born than boys. At any rate, the dearth of women would be a constant source of strife among themselves, and a constant incitement to the carrying off of women from other tribes.

The Umingmagtormiut live in close contact with the people from Bathurst Inlet, having at certain times of the year the same hunting grounds for seal, and separating only in the spring, when they move up country for the caribou hunting, from May to October. They make for Hope Bay, where the country is hilly, and was once rich in musk ox—hence the name. There are still plenty of caribou in these regions. Only last summer the herds passing Ellice River were so enormous that it took them three days to cross the delta, though the animals were always on the move. The Umingmagtormiut however, profited little by this abundance, as owing to the use of firearms following on the establishment of the trading station at Kent Peninsula, hunting had been carried on to such effect that the caribou no longer dared to cross into Victoria Land or scatter westward as they had done formerly.

The failure of the caribou hunting is a serious matter in a district where so much depends on it. Kent Peninsula itself is well on the way to becoming depopulated.

I had now to choose a field of work for myself from among these various peoples. I was at first chiefly inclined to visit the Eqalugtormiut, but as both Stefansson and Diamond Jenness had already been in Victoria Land, and had described some of the tribes farther to the north-west, I decided finally to patronize the Umingmagtormiut, who were at that time to be found on a small island not far from Kent Peninsula, where they were making preparations for the winter sealing. Here, at any rate I should be among people whom no previous explorer had described.

On the 22nd of November we reached Malerisiorfik, where they had built their camp of snow huts under shelter of a hill. There was a howling blizzard on, but all the men at once turned out to build a hut for us, while the women looked after Anarulunguaq, who was naturally a source of interest. Meat and fish were brought us in abundance far exceeding our present needs; indeed our reception from the first was typical of the unstinted hospitality with which we were treated throughout.

I had not been long among the Umingmagtormiut before I realized that there was a great difference between them and those I had just left farther to the east. A notable feature was their lively good humor and careless, high-spirited manner; we found it necessary, indeed, to check one or two of the more exuberant souls. It is perhaps this trait in their character which has led the other, milder-mannered tribes to fear the Kitdlinermiut. Certainly they had some reason to be proud of themselves, for they were greatly superior in many respects to other natives I met with in Canada. Little details such as the careful ornamentation of their hunting implements, especially their bows and arrows, showed that they had a sense of something beyond mere hand-to-mouth necessities. Their cleanliness and orderliness were remarkable, and their dress, despite the shortage of material, neat almost to the point of elegance. The women were very clever with their needle, and paid far more attention to the decorative side of their dressmaking than did the Netsilingmiut and Hudson Bay natives. I found here, moreover, an institution which I had not previously met with, to wit, that of something approaching "Sunday clothes"; they had special sets of garments only worn on special occasions, at festivals in the great dance hall.

It was not altogether easy, among these kindly and cheerful souls, to secure the necessary quiet and relative privacy for my particular work. Our hut was always full of visitors, and as they all talked at once, writing was done, to put it mildly, under difficulties. Both men and women seemed to be born traders, with a positive passion for bargaining; it was more than a form of sport with them, it was really an art. This was useful to us of course, in as far as it enabled us to add to our ethnographical collections, but on the other hand, it was not long before we had bought as much as we felt we could afford. Our friends here were not over-modest in pricing their goods. Twenty-five dollars they considered a reasonable figure for a newly killed seal; and

A detailed account of the manners and customs of the Musk Ox People would necessarily involve much repetition of matter already noted in connection with the other tribes. I will here give briefly some of the more characteristic features which distinguish them from the rest.

They are to begin with the most poetically gifted of all the tribes I met with, and their songs are not restricted to epic and narrative forms, hunting achievements and the like, but include also more lyrical elements in which feeling and atmosphere predominate. Their artistic temperament is reflected, moreover, in their actions, which do not always agree with the white man's ideas of morality. Before passing on to a consideration of their qualities as singers, poets and hunting companions, I will endeavor to show how they are regarded by the Canadian Mounted Police, who once had a patrol up here.

In 1913, two American scientists, Radford and Street, made a sledge trip through the Barren Grounds to the shores of the Arctic. At the base of Bathurst Inlet, wishing to engage assistance for the next stage of the journey, they came into conflict with the natives, with the result that both men were stabbed to death. Radford is described as an excitable person, who thrashed one of the natives for refusing to accompany them, and thus doubtless brought the disaster upon himself. It is not least interesting here to note the account given by the leader of the police patrol as to the Eskimos of Bathurst Inlet. He did not meet the actual murderers himself, but only some others of their tribe and these he characterizes as born thieves, terrible liars and altogether unreliable; indeed he would not be surprised to hear of more murders before long, as any one of them would sell his soul for a rifle.

Oddly enough, Leo Hansen and I had, while at Malerisiorfik, lived for nearly a month with two of the wanted murderers, Hagdlagdlaoq and Qanijaq, the latter, indeed, being our host for part of the time. And we found them both kindly, helpful and affectionate; thoroughly good fellows, all round. It must always be borne in mind that these people take an entirely different view of human life from that which obtains among ourselves.

Mr. Clarke and I once made enquiry among the inhabitants of one encampment, and found that out of fifteen families, there was not a single full-grown man who had not been in some way involved in the killing of another. As I have already noted among the Netsilingmiut, the man who has killed another is by no means necessarily a bad man on that account; on the contrary, such may often prove to be among the most skilful and useful members of their own little community, whose help and guidance and example are invaluable to their fellows.

At the beginning of December, Netsit, a young Eskimo, expert in folk tales, went off with me on a little journey to visit a camp in Bathurst Inlet, where men were getting ready for the seal hunting. Bathurst Inlet is a great fjord, with mountains on either side, a welcome relief after the monotonous lowlands to the east. The country here reminded me of Greenland but was somehow colder and harsher.

Netsit and I did not talk much on the way; there was nothing to make us communicative in our surroundings, and we had hardly got to know each other as yet. At the end of the first day's run, we found a comfortable snowdrift, and proceeded to build ourselves a hut for the night.

I had with me a few cigarettes, which I kept for special occasions, and this evening, after a meal and a cup of coffee, felt inclined to indulge. I therefore lit a cigarette and gave one to my companion. To my surprise, he did not light up himself, but packed the cigarette carefully away in a piece of rag.

Our snow hut would not perhaps have been considered specially warm and cosy by any save those who had like ourselves been thrashing for ten hours against a bitter wind. But as it was, the tiny blubber lamp seemed to shed a cheerful golden glow all about us; we felt in the mood for a little entertainment. We made an extra cup of coffee, and I suggested that Netsit should tell a story or so. To make ourselves thoroughly comfortable before starting, we gave the hut a good coating of loose snow to caulk any possible leaks, sealed up the entrance so that not a breath of air could get in, and then settled down in our sleeping bags, entertainer and audience ready to drop off as soon as either wished.

Here is one of his stories.

Two men met while out hunting. One of them had caught a wolf in a trap, and the other had shot a caribou with his bow and arrows; each had the skin of his beast slung over his shoulders.

Said one: "That is a very fine caribou skin you have there."

And the other answered: "That is a very fine wolf skin you have there."

And then they fell to talking about the skins, and the look and the state of them; and at last one said:

"There is more hair on the caribou skin."

"No, no," answered the other, "the wolf has more hair than the caribou."

And they grew so excited over this question that the two of them straightway sat down where they were, and the man with the caribou skin began counting the hairs in it, pulling them out one by one. And beside him sat the man with the wolf's pelt, counting hairs in the same fashion, pulling them out one by one.

But we all know that there are a terrible number of hairs in the coat of wolf and caribou, if we once start counting them one by one. And it took them days. Day after day the two of them sat there, pulling out hairs and counting, counting. . . .

And each held that his own had more than the other's.

"The caribou has more than the wolf," said the one.

"The wolf has more than the caribou," said the other.

And neither would give in, and at last they both died of hunger.

That is what happens when people busy themselves with aimless things and insignificant trifles.

I listened with interest to one story after another, and Netsit, encouraged by my appreciation, went on untiringly. He told a host of stories that evening. Of the Boy who lived with a Bear, The Bear that turned into a Cloud, The Eagle that carried off a Woman; The Woman that would not Marry and Turned into Stone; Navarana, the Eskimo Girl Who Betrayed her People to the Indians; The Man who made Salmon out of Splinters of Wood; and The Inland-dweller with a Dog as Big as a Mountain—and so on and so on. Many of them were but different versions of stories current in Greenland, and one little fable I remembered distinctly having heard almost word for word years ago at my own place in Thule. This uniformity is the more remarkable when we reflect that there has been no sort of intercourse between the two peoples for at least a thousand years.

Another odd little fable is worth noting, not least for the narrator's comment. It is one of the old stories of the Fox and the Wolf.

A fox and a wolf met one day out on a frozen lake.

"I see you catch salmon, Fox," said the wolf. "I wish you would tell me how you manage it."

"I will show you," said the fox. And leading the wolf towards a crack in the ice, it said:

"Just put your tail right down under the water, and wait till you feel a fish biting; then pull it up with a jerk."

And the wolf put its tail down through the ice, while the fox ran off and hid among some bushes on the shore, from where it could see what happened. The wolf stayed there, with its tail in the water, until it froze. Then too late it realized that the fox had been deceiving it; there was no getting the tail free, and at last it had to snap off the tail in order to free itself. Then following on the track of the fox, it came up, eager for revenge. But the fox had seen the wolf coming, and tore a leaf from the bushes and held it in front of its eyes, blinking and winking all the time against the light.

Said the wolf: "Have you seen the fox that made me lose my tail?"

Said the fox: "No, I have had a touch of snow-blindness lately, and can hardly see at all." And it held up the leaf and blinked and winked again.

And the wolf believed it, and went off on the track of another fox.

This seemed an odd sort of ending, and I said as much. "What is it supposed to mean exactly?" I asked.

"H'm, well," answered Netsit, "we don't really trouble ourselves so much about the meaning of a story, as long as it is amusing. It is only the white men who must always have reasons and meanings in everything. And that is why our elders always say we should treat white men as children who always want their own way. If they don't get it, they make no end of a fuss."

I left it at that.